Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 196

November 27, 2019

Difference and belonging

Kids, Langa, Cape Town. Image credit Anouk Pilon via Flickr.

I was raised by a single-mother and my maternal grandmother in Atlantis, a coloured township on the periphery of Cape Town in South Africa. Both of them were factory workers and neither of them completed secondary education. I am the first to have graduated from university and to have left the country to continue to study overseas.

When I turned eleven, my mother married my stepfather (for all intents and purposes he shall always be known as my father, I love that man), and suddenly my family became the family I saw on television. The famed nuclear family. Finally, no more thoughts like, ���nobody picks me up from school anymore;��� my mother or father could do that now. While my family life was hopeful, joyous and generally supportive, I want to write about my family in a different light. I want to finally write the ���sociology of the family.���

How do you love your family so much yet all your life you have wanted to run away from them? How do you begin to explain to a seven-year old mind that the fight-or-flight response should not be active when you are having a meal with the people you love the most? I wish I knew, because then I would build my time-machine and go back. See, just like the universe orchestrated a meeting that would result in this conversation, it also took away the gift of childhood which I believe is a beautiful and sacred time and space for any human being. Instead of giving me the gift of childhood, it gave me the curse of childhood. A curse that ripples now throughout my young adult life.

I remember parts of my childhood fondly. I also remember playing poppehusie, a childhood game where you basically emulate social life and what you see in your home. One day as our group of children were constructing our society (just a school, a factory and two houses) with cardboard and other junk we could find around, the first blow hit. As the older kids in the group (I was seven at the time) we were sorting out who would be the parents and consequently the factory workers or the schoolteachers. I had a culture of reading unrivalled by the other children in my area as my mother created spaces of education in my daily childhood life and thus, I had a better mastery of language and general subjects. I was cast as a schoolteacher.

My one friend then asked who I wanted to choose as my wife, and I could not answer. I looked around and they looked back at me. I did not want a wife. In fact, I wanted a husband. Some part of me actually wanted to be the wife myself. Instead of choosing, I ran back home to pee. Of course, I could not run back home every time I had to choose a wife, but as I was running, it dawned on me; I am running from something more than just the game.

When I got home, I felt confusion and anger. Why could I just not choose a wife?! It is just a game, for goodness sake! But it was never just a game. It was my first conscious encounter with gendered and sexual difference. Afterall, the game did emulate reality. In fact, the game was reality. Soon after, the second blow hit.

I sat with the discomfort for a few weeks as I was readying myself for a heart-to-heart with my mother. However, whenever I tried to approach her with this topic, I would be overcome with fear and I would start having panic attacks. (Silly me, right.) It was my mother; she had always said that if I needed to talk, she would be there for me.

But the panic attacks were correct. For although I encountered my difference head-to-head during a game of poppehuisie, my spirit and ears and eyes and body had been witnessing how my family disliked homosexuality. Unlearned, but biologically wired to pick-up sound, my ears picked up the revulsion that homosexuality presented to the people I loved most.

I then felt the same revulsion in my school. With the neighbors. I saw and smelled it everywhere. No, it was not the human excrement, cheap booze or smell of cigarettes that filled the sidewalk as I walked home from school or to the shop. It was their repulsion in response to my existence. Being called names, changing routes, being shoved from boy-to-boy in the corridor while being faux smooched by unbrushed teeth and chapped lips. Oh, who I am to judge, I was ashy after all. All of this existed around me, and that was my world from the most intimate space to the most public space.

Did I mention that I grew up in an uber-Christian household? My father is a pastor in church and my mother is religious in her own right and dutifully by his side. My parents really do love each other, and I am so glad that she found someone who could love all of her. I wish the same for me too. As a child I was loved unconditionally and with an even greater love than the love my parents shared. I was loved by God.

I grew up in the teaching that God loves me unconditionally. Of course, at seven I knew what unconditionally meant. When poppehuisie did not work out, books were my friends. My mother had stopped reading to me by then. I went on my knees, folded my hands and bowed my head. ���God, please do not let me be gay. I do not want to feel this way. I love you and I do not want to burn in hell for eternity. Really, I am sorry that I look at boys with these ideas. Please take this away from me.���

I would then get up and go and get into bed with my grandma; I shared her bed until I was sixteen-years old. She was the person I loved most in the entire world. I would also tell God that I would wake up the next morning and be cured. The next morning, I checked-in with myself. Do I feel gay?��� No. God, it worked! I ate my cereal. Prayer really works! I picked-up my bag with my completed homework. God is good! I walked to school smiling. I turned the corner and I saw him, my crush and then it all crumbled again. God, it did not work. I am still gay. I tried again. And again. And again. After all, God wants to see that you really want His help.

Perhaps I was not sincere enough. For months, I talked to a God that promised me unconditional love yet required me to dissolve myself. I did not know how else to exist. That is why I attempted suicide. See my mother does not know this. Neither does God. I stopped asking him to take the ���gayness��� away. I stopped asking him to make my inclination for high-heels and ballgowns go away. In fact, I stopped asking Him for anything. I stopped begging for God and His priests to validate my existence. I was here and I was alone. In a family, but without one. With God forever near, but never present. I belong here, but I never belonged. No child should choose between having food, love and a roof over their head or being their full self. Yet, this is what many queer children do. I chose food and love and shelter. A choice that scarred me for life, but one I saw as the best at that time.

Flash forward to my decision to leave South Africa for the time being to obtain my master���s degree in Scotland. My research is primarily concerned with how displaced Africans in South Africa negotiate spaces and experiences of belonging. Before arriving, I was someone who had no choice but to slip into the fantasy world of books in order to live through the bullying, self-hate, pain and fear.

On my third day in Edinburgh, I walked down the road, past old, towering buildings and twisting streets that gave me the illusion that I was in one of the Harry Potter books; except this time, they were not an illusion.

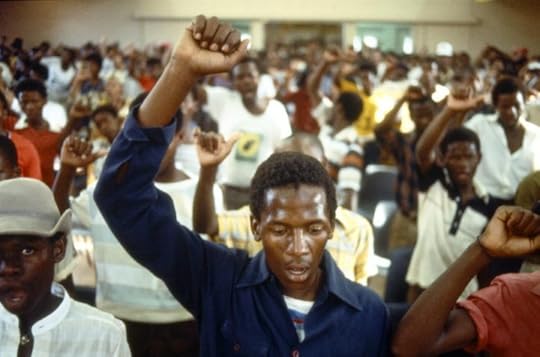

An injury to one is an injury to all

Meeting of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Johannesburg, 1985. Image credit UN Photo via Flickr CC.

The seemingly disconnected August 3, 1959 Pidgiguiti strike and ensuing massacre of more than 50 African dock and ship workers in colonial Guinea-Bissau, and the 1984 boycott of South African goods on a South African ship in San Francisco harbor by Local 10 Longshoremen Union, are related actions and together form part of the long continuum of labor actions by laborers, especially longshoremen and dockworkers on both sides of the Atlantic. These two historical events separated by two continents and an ocean underscore the importance and significance of Peter Cole���s new book on dockworkers in Apartheid South Africa and San Francisco.

It is also very personal for me. I���ve had a long association with transnational union activism and with solidarity work by trade unionists. One of my starting points was in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1961���accompanied by Lea Goldblatt, who happened to be the daughter of the ILWU���s Secretary Treasurer, Louis Goldblatt���where I brazenly challenged a presentation by Gunnar Myrdal, the Swedish author of An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Myrdal famously argued in the two-volume study, published in 1944 and funded by the Carnegie Corporation, that the US failed African-Americans less through racial bias than through the failure of American institutions to uphold the Constitution in the defense of African-American rights. Myrdal was optimistic that democracy would triumph (too optimistic, he later conceded). Nonetheless, Myrdal���s study became a key resource and a famous footnote in the 1954 Brown v. the Board of Education ruling that set the stage for desegregation.

At the Stockholm meeting I got up and criticized Myrdal for his failure to talk about how some sectors of organized labor in the US were attempting to fight racism. It was a belligerent move by an arrogant 17-year old. But my critique of Myrdal for dismissing class struggle is one that Ralph Ellison elaborated and leveled at him. Martin Luther King Jr. captured these failures in Myrdal���s argument, and in the American project, in his analysis of the necessity of considering economic justice as part of civil rights, a position of his that has largely been erased from King���s legacy until recently.

If we can now see Myrdal���s study as a corporate-financed makeover of US racism, Cole���s book shows us the possibilities that anti-racist labor organizing had and has for attacking and analyzing how systems of racial and capital oppressions are intertwined.

Cole���s work concentrates on the historical development of two sets of waterfront workers, one in Durban, South Africa, the other in San Francisco, California. The goal of Cole���s work is very clear and is achieved. He states it forthrightly when he writes:

This project compares the history of two sets of waterfront unions and their militant struggles against racism, experiences with containerization and solidarity with freedom struggles elsewhere���to draw out common and distinctive themes. In many nations and on every continent, dockworkers have proven among the most likely workers to strike and unionize.

One of the most impressive chapters in the book is when Cole discusses the 134-day strike by the ILWU in 1971-72. Exercising his skill as a trained historian, along with his political kinship with the ILWU, Cole takes the reader deep into the internal story of that critical piece of San Francisco labor history. Longshoreman, of ILWU Local 10 led by Leo Robinson, refused to offload any goods of South African origin. This puts the strikes not only in comparative perspective, but shows how unions in the US supported the global anti-apartheid movement. ILWU Local 10 had a long history of anti-racism and anti-apartheid work. Robinson, an African-American longshoreman, was a key agent in this movement, having joined the struggles for the rights of workers and anti-racism in his work.

Cole introduces the reader to riveting details about the values and lives of the ILWU leadership. Far too often has ILWU Harry Bridges been simplistically described as a ���communist��� labor leader, when, in fact, as Cole details, Bridges often took some quite conservative, almost pro-���capitalist��� approaches, such as his proposal during the strike that the ILWU should abandon its independent stance and join forces with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, a union known for its conservative, self-serving approaches to labor issues.

Another part of Cole���s research that is unprecedented and riveting in its path-making character is that on ���Striking for Social Justice.��� Very impressively, Coles puts forth an analysis of how the ILWU���s Local 10 initiated a practice of trade unionism that goes far beyond the traditional ���bread and butter��� wages issues to confront and embrace issues that were grounded in a global fight to end the South African apartheid system and expand support initiatives for liberation throughout the Southern African region. Cole prophetically illuminates a type of trade unionism that would later characterize the 2015-2019 school teacher strikes all over the United States, especially in Chicago.

Cole has written a very readable and vital, if not critical, book. In a period when so many people���notably in the US and particularly amongst youth, both white and people of color���have no idea of trade unions and the history of union struggles, to say that that ignorance must be addressed is one of the fundamental understatements of the Trump era. Cole���s contribution compares to the resonant work of Brenda Wall and Ken Luckhardt, who in the 1980-82 period produced two epic works, Organize or Starve: The History of the South African Congress of Trade Unions and Working for Freedom: Black Trade Union Development in South Africa Throughout the 1970s.

The serious reader of this book will come away with an enhanced understanding of what unionized dock and port workers have fought for all over the world. They will grow in sensitivity to what all working people are up against (whether in Maputo, Mozambique or Seattle, Washington) in this era of the ruthless ascendency and transformation of capital worldwide.

November 26, 2019

Carceral colonialism

Image credit Hern��n Pi��era via Flickr CC.

Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison in Lagos, Nigeria was originally constructed during the colonial era. Today, the prison is a notoriously overcrowded facility, incarcerating more than 5,000 people in a prison originally designed to hold eight hundred. A 2017 investigation of the facility found evidence of ���extrajudicial executions, torture, gross overcrowding and poor basic facilities.�����According to the newly renamed Nigerian Correctional Service, more than two-thirds of incarcerated people in the country, including many held at Kiri Kiri, have not been convicted a crime and are awaiting trial.

In March 2018, then foreign secretary Boris Johnson (now Prime Minister)��announced��the United Kingdom would invest ��700,000 to construct a new 112-bed extension of Kiri Kiri. But a recent Freedom of Information request to the British Foreign Office reveals, ���the UK has decided not to proceed with the proposed construction project,��� citing ���challenges associated with design and cost.���

The Kiri Kiri Prison expansion is the second prison construct project in former British colonies to be cancelled in recent years. In 2015, UK authorities announced plans to construct a larger prison in Jamaica, intended to hold 1,500 people. The British government offered Jamaica ��25 million to build the prison as part of a ��300 million aid package. The Jamaican government ultimately rejected the aid package, and with it the construction of a new mega-prison.

Both prison projects were intended to facilitate and expand the UK’s capacity to deport incarcerated Jamaican and Nigerian foreign nationals���many of whom have lived their entire lives in the UK. Under prison transfer agreements with the United Kingdom, incarcerated foreign nationals are subject to deportation and can be made to serve the remainder of their sentences in prison facilities in their ���countries of origin.�����The UK government, however, has faced difficulties making use of these agreements in both Jamaica and Nigeria due to the conditions of their domestic prisons, which do not meet UN minimum standards and have been��flagged��by human rights observers for extreme overcrowding���and in the case of Nigeria, extrajudicial killings.

Tope, a British-Nigerian community organizer based in London notes ���if they build a prison for deportees, they will have to deport people.��� She adds: [Nigerian] communities are already heavily policed and criminalized [in the United Kingdom]. Creating the infrastructure to deport people into Nigerian prisons would make that environment even more prominent.��� Tope is appalled by the evidence that, ���the [British] government is still trying finding ways to punish Nigerian people and imprison Nigerian people [decades after the end of the colonial era]. It���s shocking.”

Though plans to build deportation and prison infrastructure in ex-British colonies have been rejected, their proposals are a reflection of continued British investment in carceral colonialism. The UK’s contemporary investment in deportation infrastructure replicates historical deportation practices of anti-colonial dissidents and agitators, expelled from Lagos by the British colonial regime for challenging imperial rule within the metropole. In 1941, for instance, the President of the Nigerian Union of Railwaymen, Michael Imoudu, was deported from Lagos to his hometown in the Benin Province and labeled a ���potential threat to national security��� for his labor organizing. The British have long used practices of deportation and incarceration to control the movement and political resistance of Nigerian colonial and post-colonial subjects.

Researcher Connor Woodman��notes��that for hundreds of years the British colonies served as laboratories for the production of British policing and incarceration tactics. The existing Kiri Kiri prison in Nigeria, for instance,��was built��under British colonial rule. The British also built at least three of Jamaica���s seven adult prisons. The contemporary dehumanizing and overcrowded conditions of these prisons reflect the violent British carceral practices under which they were initially built.

For instance, contemporary Nigerian laws permitting both the death penalty and the criminalization of homosexuality were introduced by British colonial governments. Today, Nigerians can be sentenced to prison in overcrowded colonial facilities under colonial laws, and subject to violent colonial punishments. But, the UK���s immigration regime extends no obligation or accountability to people who flee this ongoing colonial injustice. Instead the government invests in their deportation from the empire���s territorial center.

The UK���s attempts to (re)invest in deportation infrastructure designed to incarcerate immigrants from former colonies is evidence it has no plans to account for the continued displacement of people in this post-colonial era. On the contrary, these proposed prisons are evidence the British empire is reinvesting in the machinery of deportation, colonial violence, and erasure.

November 25, 2019

Greening the Sahel isn���t enough

Still from film The Great Green Wall.

���I want my continent to be a place where people can dream and believe that their dreams are valid���that they can realize those dreams,��� says Inna Modja, the Malian musician and activist at the beginning of the documentary The Great Green Wall. Modja���s wish, it turns out, isn���t merely abstract. Rather, it���s wrapped up in a specific vision: an initiative called the Great Green Wall. In a series of title cards, we learn that the Wall is an African-led plan to combat desertification, migration, and conflict in the Sahel region by planting a wall of trees������the largest living structure on Earth������across the continent. ���I wonder if it���s going to work in the end,��� Modja says. ���I���m searching for answers.���

And search she does���at least when it comes to geographic navigation. Over the course of 90 minutes, Modja travels across stretches of the proposed 8,000 km wall, making stops in Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, Niger, and Ethiopia. Along the way, she meets with farmers, activists, and victims of conflict who stand to benefit from a regenerated landscape in the Sahel. Modja is a compassionate and often endearing narrator, and she diligently highlights the challenges facing the region. But her investigation into the Wall���s prospects is glaringly uncritical, and the answer to her central question���Will it work?���is largely unexplored. What���s left is mostly a bunch of well-intentioned hot air.

Modja���s limitations as a narrator are, unfortunately, baked into the film���s DNA. The Great Green Wall is co-produced by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), and it is in fact the second film to figure into the Convention���s public awareness campaign for the Great Green Wall. (The first is an eight-minute-long VR short.) Modja herself is a UNCCD Land Ambassador, so clearly it���s not her job to objectively scrutinize the Great Green Wall; it���s her job to boost it.

It���s unsurprising then that the film often has the feel of a feature-length advertisement, one submerged in the perspectives, lingo, and personnel of international governance. In the film���s final scenes, Modja interviews UN Undersecretary General Monique Barbout, then addresses a UN conference in New York. For a film obstensibly promoting African self-determination, the UN���s handprints are oddly and conspicuously pervasive.

Modja���s personal interventions in the film are, at times, equally out of place. The singer is, we learn, working on an album inspired by the Great Green Wall, and much of the film documents its making. Throughout her travels, she creates music with a host of prominent artists, among them Didier Awadi (of Positive Black Soul), Songhoy Blues, Waje, and Betty G. In scenes from recording studios and live concerts, Modja and her talented collaborators are a pleasure to hear. But the proximity of Modja���s creative pursuits to stories of hardship and precarity can create a strange dissonance.

Still from film The Great Green Wall.

Still from film The Great Green Wall.At a school for orphans in Nigeria, for instance, Modja and Waje sit down with two girls, one of whom lost her father to Boko Haram. Modja praises the girls for their bravery, then sings a song to them. Later, dozens of the girls gather outside and sing one of Modja���s own songs to her. ���I didn���t know they were going to perform it. Oh my god,��� Modja says, wiping tears from her eyes. It���s an oddly self-serving moment���and unfortunately, not the last.

Modja clearly harbors a great deal of sympathy for the people she meets during her journey. But the film���s imperative to keep the action moving along makes her engagements with those people���and their suffering���frustratingly short. The morning after her trip to the school, for instance, she tells Waje that she couldn���t sleep through the night. Waje, also deeply affected, responds, ���I���m uncomfortable with the fact that I will probably go back tomorrow and live my life as always.��� That���s an intriguing confession, but the conversation ends there and the film quickly moves on. Before we know it, Modja is back on a bus headed toward her next destination, gazing melancholically out the window at passersby���as she does often throughout the film. As she passes, silent, lone figures in the crowded streets gaze back, filmed in slow motion from a moving vehicle by director of photography Tim Cragg. The shots are lovely to look at, but their brevity only seems to accentuate the distance between Modja and the people of the Sahel.

There is also a glossing over when it comes to the Great Green Wall itself. With only 15 percent of the Wall completed since its approval by the African Union in 2007, the project is, Modja readily admits, ���more a vision than reality.��� While the film is candid about the funding challenges impeding the project, however, it is far less forthright about some of the project���s historical shortcomings.

First conceived as a wall of trees across the Sahel, the concept of the project has evolved over the years, after scientists pointed out that, for a number of reasons���among them the fact that large swaths of the proposed Wall were uninhabited, meaning that no one would be around to care for the young trees���a literal green Wall in the Sahel was doomed to fail. Today, the initiative instead stresses indigenous land use techniques that restore the lands in the Sahel threatened by climate change. The Great Green Wall can, according to the project���s technical director Papa Sarr, more accurately be described as a mosaic of green development rather than a ���line.��� The film, however, doesn���t acknowledge the thoughtlessness behind the initial proposal. Nor does it shy away from highlighting the photogenic stretches of the Wall where the questionable practice of linear tree planting is still underway.

Some examples of the Wall���s new direction are, nonetheless, given air space. Take the Ethiopian farmer and activist Abu Hawi. For more than 30 years, he���s led a grassroots effort in his community to make desert lands fertile through ancient tools and techniques. In the film, though, Hawi���s success isn���t framed as the result of his smarter and more humble approach to reforestation. Instead, it���s held up as the product of Hawi���s sunny disposition and work ethic. ���Because I believed it was possible, because my thinking had changed, I was able to bring change to the land and to peoples��� mindsets,��� he says.

Africans surely do have a part to play in boosting their resilience to climate change, and the Great Green Wall can surely be part of it. But the solution to the Sahel���s woes aren���t merely attitudinal; they���re political. The Great Green Wall, however, makes no mention of global greenhouse gas emissions���a key political matter that will, more than anything, determine the Sahel���s fate. It is important for Africans to dream big, as Modja suggests, but if the world���s biggest emitters don���t rapidly reverse their destructive habits, those dreams will rot���and all the trees and good feelings in the world won���t be able to revive them.

November 24, 2019

Our women on the ground

Waiting on the train in Tunisia. Image credit Xavier Donat via Flickr CC.

���What was it like to be a woman over there?��� Hannah Allam recounts being frequently asked of her time reporting from Iraq in the first essay of Our Women on the Ground. The collection of essays by female journalists, edited by Lebanese-British journalist Zahra Hankir, provides an account of ���life in the field��� across the region. The reply Allam intends to give is ���Well, I���ve never been there as a man, so I���m not sure I can compare.��� But it often escapes her, she says, as the faces of the women she encountered come into focus. As one reads on, digesting one powerful story after another, this mental detour is unsurprising.

In recent years, there have been many initiatives and individuals working to remove stigmatization and stereotype around victimization and domination of Arab women. At times, the conversations that emerge can seem ridiculous or end up simply perpetuating the very narratives they seek to dispel. These stereotypes are often combated most effectively by those not explicitly trying to counter them: Just real stories about real people. This is what Our Women on the Ground offers.

At times harrowing and tragic, with dashes of that special brand of Arab dark comedy, what ultimately emerges is a spectrum of stories exhibiting pain, strength, resilience and a kind of collective trauma that is omnipresent in the region but rarely spoken of. The book is complicated. The authors��� backgrounds and stories are as diverse as the nations that make up the Arab region. Different passages will stand out for each reader, depending on their views, experiences, and relationships to the places covered. Some of the essays are riddled with tragedy and raw sadness, like the startlingly honest account of loss and self-preservation by journalist Nada Bakri, wife of the late New York Times foreign correspondent Anthony Shadid. Others tell disturbing stories of violence and danger as it unfolded around them.

The essay ���Spin��� by Natacha Yazbeck is arguably the most candid and darkly humorous account of the ethical dilemmas faced by journalists with regional connections covering difficult beats. To say her description of guilt and internal struggle is brave feels like an understatement. It comes to a head in the final pages, where she writes:

��� But I do. I need forgiveness. Every day. Because complicit does not even begin to describe it. To write from, and in, that same pipeline that disfigured my people, my history, my land, my family, to write in the very language and for the very people who did it, which is also your language and who are also your people, and to do it so that you are liked, so that you are tagged, to be popular because your brand is your currency. To sell out every minute of every day, and to be thanked for your part in our very disfiguration. To be willingly complicit in this in that fact that my tax dollars fund the wheels on the planes bombing the babies of my people.

Frankly, this stunning self-awareness and (overly) harsh self-critique is balanced by other essays tending toward the opposite. Still, however you may feel about the authors at the end of every chapter, their characters and experiences are laid bare. As writers, journalists, and editors working in the region we all make choices; and one cannot deny the fortitude needed to candidly share those choices with an anonymous audience.

Some chapters of the book also offer rare insight into areas of the Arab world where English-language coverage is spotty at best and usually of one note. Yemeni photojournalist Amira Al-Sharif���s essay was a refreshing break from the horrific but inconsistent coverage we often see from the war-torn country. She has held strong to her belief that her people deserve a more complex and nuanced narrative, and has done her part using her camera to tell stories of the strength and resilience of Yemeni women that she has compiled into a project called ���Yemeni Women with Fighting Spirits.���

But even with how candid much of the content is, some choices are questionable. In one case, an author opts for direct translation of all Arabic until until one protest chant: ���Allah, souria, hurriye, wa bas��� choosing instead to indicate it was ���calling for freedom in the country.��� This stood out to me in a volume that is, by its very nature, in opposition to so many stereotypes of women, society, and life in the Arab world. Why choose not to include the translation of God, Syria, and freedom for an English-speaking audience? Whatever the reason, it smelled of an oft-ignored breed of self-censorship. Not the self-censorship for self-preservation practiced by so many journalists in the region, but the kind that makes us apologetically ���from the region.��� This is a choice to not emphasize���maybe even ���sanitize������the cultural importance of aspects of religion because we assume our audience will simply not understand, or fear they will use it as fodder for their xenophobia. One would hope that within content where truth and reality are presented in such an unapologetic manner, cultural nuance like this could be included. But perhaps there was not space, and perhaps I am splitting hairs.

Finally, the volume disproportionately represents journalists working for major western publications or networks, with only a handful representing local outlets from the region. Editor Zahra Hankir addresses this issue and the challenge of choosing and capping the number of contributors in her introduction, but the imbalance is palpable as one works through the book. This ultimately detracts from its overall strength, but perhaps leaves space for another volume focusing only on the stories of lesser known local sahafiyat.

November 21, 2019

Bottom-up hustling in Nairobi���s slums

Image credit Magdalena Chulek.

According to United Nations data, one in eight people in the world live in a slum. In Nairobi, which has nearly four��million inhabitants, the percentage is much higher���60%. These people function in nearly 200 slums, which make up less than 5% of the city���s living area. The vast majority work in the so-called informal sector. The 2017 Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Economic Survey shows that this sector provides as many as nine out of 10 jobs in Kenya.

Slum dwellers��� day-to-day activities create a functional (although insufficient) economic system, which makes it possible for them to exist like this for years. In an upcoming article, entitled ���Hustling the mtaa way: the brainwork of the garbage business in Nairobi���s slum,��� in the African Studies Review, I delve deeper into how stability of life in slums is built by the inhabitants��� everyday, bottom-up hustling practices.

One of my informants, Merry, lives in Korogocho, one of Nairobi���s slums. When I met her, she was a picker working with a group of women in Dandora, the city���s largest landfill. In very hard and dangerous conditions she picked and selected waste for recycling. Merry often said she dreamed of a formal job which would give her a sense of stability. She was happy when she found work as a housekeeper. Yet after three weeks she said she ���quit��� and was ���independent��� again. At the same time, on the other side of town, in Kibera, an iconic slum, Fredrick looks for ways to make money. He spends part of each day talking with friends and chewing miraa leaves, and making a living as a middleman for various kinds of transactions. Frederick doesn���t look for work outside of the slum: ���I won���t be able to make money outside. Kibera gives me the opportunity to get money ��� If I���m not here, the opportunity passes.��� He also stressed ���the need for autonomy.���

For people who do not live in slums, such decisions might be hard to understand, because the complexity of everyday slum life is lost in the way it is portrayed from the outside. Media portrayals focus on the uncertain and sometimes transient nature of slum dwelling and economies, characterizing lives dominated by overcrowding and lack of planning. Yet, slums are lasting spaces, very much a part of the city���s topography. What���s more, they also constitute permanence and home for generations of people. Understanding the behaviors of slum inhabitants must also comprise the wider realities that influence their everyday practices. These cannot be understood without understanding the patterns governing their relationships and how slum conditions impact their decisions.

Paradoxically, hustling often allows slum inhabitants to combat uncertainty on their own terns and in accordance with their abilities. For Merry, the landfill is a stable source of income, one that is compatible with the rhythm of her life. Similarly, Fredrick incorporates making money into the specificity of life in Kibera. Here, what is of note is the organization of time and space in which work and personal life permeate each other. Lack of an imposed schedule allows Merry to take care of her children and gives Fredrick a sense of power and dignity.

For hustlers, what is of key importance is not just making money but above all being part of a network of relationships which make it possible. Although their earnings are irregular, as they themselves say, ���they exist.��� Therefore, it���s important to find one���s place within the network of economic interdependencies, just as Merry and Fredrick have. Merry is ���located��� between other pickers, those who buy waste to be recycled and those who sell valuable wares recovered from the landfill. Fredrick, on the other hand, positions himself as an indispensable element in the dealings between shop owners and officials. This is a kind of interdependency in which various people ensure they have the opportunity to act.

Understanding the conditions of hustling in slums is important because, although these are small-scale practices, they concern thousands of people like Merry and Fredrick and significantly impact the reproduction space and community. Everyday routine behaviors to do with hustling, such as walking or sitting in given locations, create local spaces.

Hustling allows slum dwellers to survive but it doesn���t enable them to overcome poverty. A Korogocho inhabitant summed it up by saying: ���hustling allows us to survive but not to live.��� For slum dwellers stability is ambiguous. It has a certain quality in which slum conditions become the norm, and very difficult to overcome.

November 20, 2019

Mauritania���s past doesn���t want to go away

Mauritania. Image credit Francisco Freire.

Contrary to what happened in most postcolonial transitions in Africa, in Mauritania the post-independence government initially was not associated with any liberation movement. It was, in fact, composed of people who had been, in most cases, educated in France and groomed to govern independent Mauritania by French colonial administrators. It is probably because of this factor that today, more than 50 years after Mauritania���s independence, we are (finally) faced with a public debate centered on the country���s colonial heritage. A debate in which local actors are blatantly labeled as ���resisters��� or as ���collaborators.���

But the ongoing muqawama (resistance) debate in Mauritania should not be solely associated with the country���s colonial past. In fact, it reenacts an ancestral rivalry between the Zawaya and Hassane social status groups (tentatively translated in English as ���religious��� and ���warrior���). The former constituted the bulk of the country���s political structure during the national independence period, while the latter, favoring Hassane values, are currently finding themselves emboldened, notably by the policies of former President Ould Abdel Aziz���s (2009-2019) policies and, quite possibly, by those of his designated successor, Ould Ghazwani (in office since August 2019).

The Hassane and Zawaya labels are generally (but not exclusively) associated with the different status groups traditionally acknowledged in the western regions of the Sahara. On the ���resisters��� side, one could identify different Hassane political leaderships, which led an effective opposition to colonial forces (notably in the initial decades of the 20th century). By contrast, the ���collaborator��� label tends to be associated with Zawaya status actors from the southwestern region of present-day Mauritania, who, in fact, accepted the presence���deemed inevitable���of French colonial forces in the northern margins of the Senegal River. These social markers must, however, be used with caution. They provide an overall framing of the colonial debates as perceived locally, but they must, at the same time, give room to many exceptions which complicate this largely idealized social design. One particularly poignant example of this has to do with the assassination of the well-known French colonial administrator Xavier Coppolani in 1905. The raid that culminated in Coppolani���s death was led by Sharif Ould Moulay Zein, from a Zawaya or collaborator background, who currently epitomizes the ���resistance narrative��� in Mauritania.

This late-decolonial dispute between collaborators and resisters confirm that the so-called ���peaceful transition��� in Mauritania wasn���t unanimously understood as such in the country. It also confirms, to a very large extent, the pervasive character of a traditional social order where the Hassane and Zawaya, the two ���noble��� components of this structure disputed political privilege. This social design is associated, in particular, with the hassanophone populations (speakers of hassaniyya) of the western regions of the Sahara. This structure also incorporates various groups of tributary status, with a clear demographic emphasis on the Ha���atine population, of slave descent.

In 1960, the leading figures guiding Mauritania���s transition to independence were affiliated with Zawaya social status groups from the southwestern Trarza region of Mauritania. Moctar ould Daddah, the first president of the country, and himself a product of southwestern Mauritanian religious scholarship, stayed in power for 18 years, but after 1978 a succession of different leaders seemed to have curbed the pivotal role that the Trarza Zawaya held for many decades. This is the historical background that culminated in President Ould Abdel Aziz���s public defense of the muqawama as an official state policy. The adoption of this narrative in major public and media spheres reopened the country to a debate, which had been muted for a long time but that wasn���t at all concluded.

Currently, some of Mauritania���s more distinguished political figures defend the presentation of the country as a nation marked by the blood of the martyrs who fought against French colonialism. Two red stripes, symbolizing the blood of anti-colonial combatants, were added to the national flag in 2017, and the new Nouakchott international airport was named after the battle of Um Tunsi (1932), in which a French-led military expedition (which included Mauritanian soldiers) was defeated.

November 19, 2019

Lungu’s Livingstone

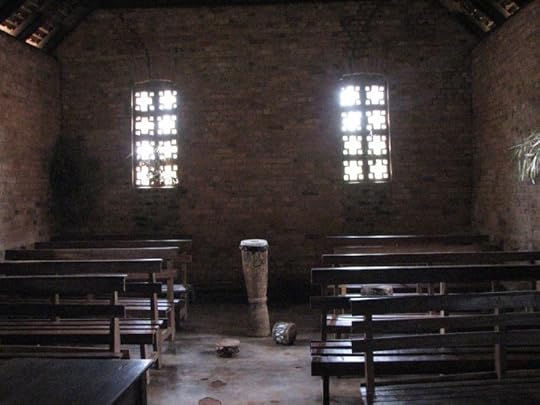

Church transept (and instruments). Image credit

Seyemon via Flickr CC.

During an October 2015 speech, Zambian president Edgar Lungu quoted a prayer attributed to the Scottish explorer and missionary David Livingstone. Kneeling on what would one day become Zambian land, Livingstone is said to have prayed, ���Dear God, on this soil on which my knee bends raise a mighty Christian nation that will be a light to other nations.��� (As Chammah Kaunda has pointed out, Lungu���s speech altered the quote slightly). This prayer is sometimes described as the missionary���s dying utterance, an idea that anchors the recent refurbishment of the David Livingstone Monument at the site of his death in Zambia���s Chitambo District. The contractor who oversaw the project told me that when his team arrived on the site they were shown a stake in the ground and given strict instructions to place Livingstone���s statue in that precise location���the exact point at which Livingstone was believed to have died, and where Zambia was first declared a Christian nation.

I have been studying Christianity in Zambia for more than fifteen years, and it is only recently that I have begun to hear church and government leaders quoting this (probably apocryphal) prayer from the country���s most famous missionary. Before that it was the late Pentecostal president Frederick Chiluba, rather than Livingstone, who was credited with making Zambia the only self-declared Christian nation in Africa. Chiluba initially made ���the declaration,��� as it is commonly known, during a press conference soon after his election in 1991. Five years later it was enshrined in the preamble to the Zambian constitution.

Since Chiluba���s presidency, subsequent Zambian heads of state have not made much use of the declaration���that is, until the election of President Lungu in early 2015. Lungu and the Patriotic Front (PF) government have rolled out a bevy of explicitly Christian policy initiatives, including the creation of a new Ministry of National Guidance and Religious Affairs, establishment of the National Day of Prayer as a public holiday, and a commitment in the Seventh Development Plan to draw on ���Zambia���s Christian heritage as a standard of governance approach.��� It was only after Lungu came to power that I started hearing church and state leaders attributing the declaration to Livingstone, rather than (or in addition to) Chiluba. I found this shift puzzling���why were those in power suddenly insisting that it was Livingstone who had first declared Zambia a Christian nation?

In responding to this question, the first thing to note is that not everyone is compelled by the government���s mobilization of Christian rhetoric and ideas, which have drawn sharp criticism from many Zambians. The government strategy in the face of such critiques has focused in part on drawing a distinction between its actions, which can always be attributed to the party or president���s political interests, and God���s divine plan for Zambia, which by definition extends far beyond such worldly concerns. Here is where Livingstone comes in.

Attributing the declaration to Livingstone, rather than Chiluba or any other recent political figure, makes the country almost primordially Christian. If the first Christian to walk into what is now Zambia uttered the first version of the declaration, then Zambia became a Christian nation at the first moment such a thing became possible. Understood in these terms, becoming a Christian nation was Zambia���s destiny; as the Pentecostal writer Liya Mutale puts it, ���God had ear-marked [sic] us to be a Christian nation before we were formed��� (2015, 5).

If the country has, in this sense, always already been Christian, then recent efforts to ���actualize��� the declaration, as the government puts it, are bigger than the current president or the ruling party. By suturing some of its most prominent policy initiatives to established Pentecostal ideas about God���s plan for Zambia, the government has effectively insulated itself from critique. For, if what the PF is doing is simply an extension of what God has been doing in Zambia all along, then any criticism of, for instance, the National Day of Prayer amounts to criticism of God rather than criticism of the ruling party. It is no surprise that such critiques do not go down well with Zambian Pentecostals, who are heavily invested in the idea that their country has a unique divine destiny.

What does this example tell us about Pentecostal politics more generally? Based on my earlier research with small, locally initiated Pentecostal congregations in Zambia, I have argued that this form of Christianity is a site of potential political critique. One of the core tenets of Pentecostalism is that God���s power and blessing are equally available to everyone regardless of status, which means that through Pentecostal adherence those without power or position or wealth can claim those things as their divine right. What the example of contemporary Zambian state politics shows us, however, is that these same ideas do very different political work when employed by the powerful. Pentecostalism���s egalitarianism can make it difficult to call out abuses of power, as those in authority can simply reaffirm the idea that all power���theirs included���comes from God, making God ultimately responsible for the outcome of their actions. Seen from this angle, it is possible to argue that Pentecostal adherence gets in the way of political participation, or at least political critique. While this is indeed sometimes the case, I think it is ultimately more productive to map out the multiple and contradictory ways that Pentecostal discourses are mobilized politically, rather than focus just on the points at which this religion serves the interests of the powerful. Only then can we fully appreciate the wide-ranging effects that Pentecostalism has on politics around the world, not least in Africa���s only self-proclaimed Christian nation.

November 18, 2019

Fanon’s mission

Image Credit Leo Zeilig (I B Tauris or HSRC Press -

South Africa)

Frantz FanonWe must work and fight with the same rhythm as the people to construct the future and to prepare the ground where vigorous shoots are already springing up ��� The problem is to get to know the place that these men mean to give their people, the kind of social relations that they decide to set up, and the conception that they have of the future of humanity.

In a fine story from Toni Cade Bambara���s The Seabirds Are Still Alive, a character named Jason says to another: “We need a lesson on architectural design.��� He starts to clarify by saying, ���the politics of ������ but his co-teacher and comrade, Lacey, completes his thought in automatic, absolute agreement. Together they operate a community school for black children whom they are trying to walk home, one at a time, across a landscape made more bleak and white by a strangely brutal climate change���Arctic snow in the ���hood (highly symbolic, needless to say).

This brilliant narrative set-up allows Bambara to supply wicked commentary on contemporary black-white spatial dynamics in architectural white America. They return from an African art exhibit at some museum to survey an enemy cathedral lording over their tenement confines; a man-made lake fabricated to elevate rents as well as some rich white ego; and some new cement school built like a prison intimidating their neighborhood, which���after recent counter-insurgent reconstructions���today lacks all ���territorial control,��� any semblance of ���a sovereign place.���

The revolutionary schoolchildren in this story represent a future one must fight for, the assumption of their right to any future at all, and a future of their own making and design. The narrator states over and again, till the very end of the tale, ���I���d like to meet the characters who designed these places ��� in any alley ��� with my chisel.��� Both teacher and wannabe ���assassin��� now, Bambara dreams of the revolutionary violence (or counter-violence) long associated with Frantz Fanon���whom she also recalled in her classic ���On the Issue of Roles��� from The Black Woman: An Anthology.

The Fanon of Toward the African Revolution wrote regularly about the ���rights of peoples��� over and against the ���rights of Man��� within his extended, extensive quest for a new humanism ���made to the measure of the world.��� Often cast as a prophet in hindsight, he wrote routinely of history and the future, not to mention generations, as he launched his prescient critique of neocolonialism with its ���puppet independence��� masquerading as bona fide liberation and decolonization.

After all, besides those who can only read a certain set of pages from Black Skin, White Masks in a most specific fashion, what consumers of ���critical theory��� cannot recall this one line from The Wretched of the Earth: ���Each generation must out of relative obscurity discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.��� Many never reach the end of the same paragraph, it appears: ���As for we who have decided to break the back of colonialism, our historic mission is to sanction all revolts, all desperate actions, all those abortive attempts drowned in rivers of blood.���

On closer scrutiny, however, Fanon is seen to deploy this forward-thinking generational idiom all across this classic book, which straddles the limit between the mortal and the posthumous-immortal, textually, toward a very different ���Afro-futurism��� to be sure.

The idea that a generation or more not yet born could, let alone should, have rights of any sort would sound counterintuitive insofar as it is meant to give voice to an alternate intuition or mode of thought. Yet, this is exactly what is found in Fanon. It is easy to retrace his meditations on human as well as non-human architecture, whether spatially or metaphysically speaking, perhaps especially between the ���Pitfalls of National Consciousness��� and ���On National Culture” chapters of The Wretched of the Earth, which is hardly to exclude the statuesque chapter simply entitled ���De la violence��� or previous books and writings.

Plainly, The Wretched of the Earth was on a mission of the future for present and future generations from the start. Early on, Fanon succinctly defines the ���historic mission��� of the ���national middle class,��� which was ���that of intermediary������mere ���middle-men.��� This idea plays out like a militant musical refrain in Fanon who writes that the leaders of this elite ���imprison national consciousness in sterile formalism��� (as if the subject were art or architecture, interestingly). The people are left in need of a plan of thought and action that can give satisfactory ���form or body��� to this consciousness and its foundations. Rather architecturally still, he notes:

Then the flag and the palace where sits the government cease to be the symbols of the nation. The nation deserts these brightly lit, empty shells and takes shelter in the country, where it is given life and dynamic power. The living expression of the nation is the moving consciousness of the whole of the people; it is the coherent, enlightened action of men and women.

Deposing abject leaderism, Fanon climaxes this key dimension of his thought with a new arrangement���whereby the ���duty��� of those at the head of any movement is ���to have the masses behind them.” To enter history is to have a future, a future with rights to human being, no less, as heretical as this notion turns out to be. It is not to emulate European men who like their neocolonial ���intermediaries��� have also ���not carried out the mission which fell to them.��� Undeniably, this was and is a work threaded by futuristic concerns for the generations to come.

What���s more, another central element of a ���rights of future generations��� motif was launched in Fanon���s El Moudjahid articles in the late 1950s and so throughout the polemical texts collected as Toward the African Revolution, arguably the least-read Fanon among academic critics in the West. Here we encounter the ���rights of peoples.��� Constantly, he shifts the point of analysis from individuals to peoples���populations, in the plural. The ���humanism��� of France���s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is denounced, exposed, discarded. It is to be replaced, in Fanon���s epic, epochal mission, by a new humanism vested with the ���rights of peoples,��� which he elaborates as the ���right to self-determination.��� This would be the ���right of peoples��� to selfhood or peoplehood itself. The cyphering of ���peoples��� appears many times and many ways in Fanon to redraft basic philosophical conceptions for every phase of this liberation struggle ���

As it stands, Fanon may not be known for ���designing or constructing buildings��� in this or that metropolis, but he began his first book with reference to the architecture of his ���sociogenic��� work. He went on to transform the architecture of psychiatric treatment in the most literal, logistical terms in Blida, Algeria���a spatial practice of ���ergotherapeutic��� innovation which persists there, in a new century, on the hospital grounds now named after him. It compliments his prosaic treatment of engineers, statues, ports, airdromes, bridges, palaces, urbanity, and the symbolic Casbah, for starters. Some etymologies of ���architect��� or ���architecture��� denote ���weaving��� or ���fabricating,��� as in the crafting of written or spoken texts. They can also invoke ���one who plans or contrives��� anything, as in one who plots like Fanon in a conspiracy of worldwide revolution, anti-colonial and anti-neocolonial alike. This is not the ���architect��� as ���construction supervisor��� or ���director of works������some ���master builder.��� This would be ���architectonics��� of poiesis and revolution and so arguably maroonage: Fanon rethinking our whole atmosphere as the architect of rights, futures, generations.

���I���d like to study the brains of these planners up close ������ says Toni Cade Bambara���s cityscape narrator for the ���Broken Field Running��� story from her The Seabirds Are Still Alive collection: ������ Forceps in hand.��� One of her schoolchildren asks what they will do with ���that ugly school��� with the cyclone fence built to intimidate and incarcerate their neighborhood-community, that is, after their new day has come. The reply is that it should take place as a wing of the ���Museum of the Revolution ��� We can put the ���Crimes against the People��� section in it.���

To no small extent, these youth signify the element that would grow up to be hip hop and come to represent pan-African Fanonism of and for future generations: La Rumeur in France, for instance; Moonaya and Nix of Senegal with Fatou Kande Senghor���s Wala Bok projections; Lauryn Hill voicing Concerning Violence so spectacularly in cinema with a related concert tour to follow; MC Majnoon and El Herraz Nomade in Algeria���besides Donquishoot and Diaz of MBS, who spit ���La Bataille d��� Alger 2016��� and then loop clips of Gillo Pontecorvo���s iconic film for a truly stunning music video. The rights of present and future generations get writ large. The circumstances are dire, yes. The stakes of the ���historic mission��� are no less unclear.

As Huey P. Newton of the Black Panther Party once wrote, ���The greater and more immediate problem is the survival of the entire world. If the world does not change, all its people will be threatened by the greed, exploitation, and violence of the power structure.��� The revolutionary Black Radical Tradition, young or old, is no slouch on the matter of human-architectural preoccupations. And then there���s that self-styled ���Marxist-Leninist-Maoist-Fanonist,��� George L. Jackson:

We have a momentous historical role to act out if we will. The whole world for all time in the future will love us and remember us as the righteous people who made it possible for the world to live on ��� I don’t want to die and leave a few sad songs and a hump in the ground as my only monument. I want to leave a world that is liberated from trash, pollution, racism, nation-states, nation-state wars and armies, from pomp, bigotry, parochialism, a thousand different brands of untruth, and licentious usurious economics.

November 17, 2019

The politics of Ethiopia’s annual Thanksgiving celebration

[image error]

Irreecha. Image credit Serawit Bekele Debele.

The Irreecha, which takes place at the sacred lake of Arsadi, is an annual ritual celebrated by the Oromo and other peoples at the end of Ethiopia���s rainy season and when blue skies usher in September/October. My book, Locating Politics in Ethiopia���s Irreecha Ritual, explores the country���s politics by making this popular thanksgiving ritual its entry point. The book is about (re)centering ���other voices��� that hegemonic structures and discourses silence. It is about the unemployed youth, women, elderly and spirit mediums whose take on politics and religion rarely finds an outlet because their meaning-making processes, practices and experiences do not always mobilize conventional vocabularies and venues.

In the book, I situate Irreecha in the context of Ethiopia���s post-1991 socio-political transformations, following the toppling of dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam by the current ruling Ethiopian People���s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The decades under EPRDF���s rule are marked by profound changes in the socio-cultural, economic and political domains.

With the introduction of ethnic federalism, previously marginalized groups of people enjoyed a certain degree of freedom to promote their ethno-religious and cultural heritages. Owing to this momentum, Irreecha became popular and it received attention from various sections of Oromo society. A previously marginalized ritual performance was now endorsed by Oromos across educational, generational, religious, gender and class differences. Soon, it became one of the most defining elements of an Oromo national identity: a highly politicized site where Oromo identity was asserted and celebrated. What was once a local ritual, confined to Bishofu (a town formerly called Debre Zeit) and its surrounding rural areas, expanded to become a national celebration. Besides its (re)positioning in the discourses and narratives of national identity, Irreecha also attracted the attention of politicians of divergent persuasions for ���doing politics.���

The post-1991 Ethiopian state under EPRDF, while initially open to the political expression of Oromo and other groups, was soon characterized by increasing authoritarian tendencies leading to dwindling possibilities for open popular political participation. Irreecha came in handy to channel grievances, criticisms, resistance and alternative political propositions against state dictatorship and the lack of freedom. As such, the ritual became a launching ground for Oromo identity and emerged to be central to articulating contemporary political demands.

This reached a climax in the #OromoProtest years of 2014-2016, when the youth openly protested against the then government. The October 2016 Irreecha celebration was notable for the pronouncement of the slogan ���down down woyane��� (down down TPLF)���a reference to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which had evolved into the then dictatorship. Against the backdrop of years of protest, October 2016 was a moment when the Oromo youth (mostly known as Qerroo) openly showed ���the will not to be governed��� and demanded change at all costs.

The government reacted by by declaring a state of emergency that lasted for a few months. Despite being remembered for the death of hundreds, it is at the same time significant as ���a point of rupture��� that ushered a transformation that led to the change in the political domain in today���s Ethiopia.

This is the socio-political context in which my book arose. In the course of conducting research for it, I asked: what constitutes politics from the point of view of various stakeholders? In what ways do state politicians and their opponents, (mainly the Oromo Liberation Front) and their respective supporters appropriate Irreecha as a political space to mobilize the populace around their ideologies? How do grassroots politics operate at Hora Arsadi (the sacred lake where the ritual takes place) and what are the mediums through which these politics are articulated? How do political subjects shape how we understand political processes in Ethiopia in particular, and Africa in general?

At the same time I pondered if we can ascribe a singular and coherent meaning to Irreecha. For example, is it really a monolithic spiritual/cultural event/practice/performance? How do the tensions between pan-Oromo (Orommuma) and pan-Ethiopian ideologies play out at Irreecha? Does Irreecha have a history(ies) that speaks to and enables us to understand broader cultural/religious and socio-political processes in today���s Ethiopia? How do we account for archives and voices that hegemonic narratives about Irreecha omit?

As the title suggests, the book is an attempt to find politics elsewhere, as it is practiced by those who are on the margins. The book goes beyond interpreting Irreecha as solely an Oromo ritual and situates it within a wider framework, so as to interrogate the deeper political and religious realities of and practices in the country. By locating Ethiopia���s politics in a ritual most Oromo political elites confine to the limits of Oromo national identity, I tried to situate the Oromo political struggle as well as Irreecha within the wider national context.

Irreecha offers a window into contemporary political issues. I believe the ritual can be used to rethink the meaning of Ethiopia and enrich that meaning by embracing various narratives. Towards this end, it is high time for scholars to pay attention to other vocabularies and ways of articulating politics. In this spirit, I hope the book stirs much-needed conversation and engagement with the meaning of politics, political subjectivities and the production of political spaces other than those of the state, civil society and political parties.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers