Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 191

February 3, 2020

Should sleeping giants lie?

Talai Elders Kibore Cheruiyot Ngasura and King George Kipnegetich discuss their experiences of forced removal with one of the authors at Kericho���s Tea Hotel in 2014. Credit Alex Dyzenhaus.

Across Africa���s settler states, the issue of reparations for colonial wrongs has gained traction. In South Africa, Namibia, Kenya and Zimbabwe, land restitution remains an issue of contention among groups whose displacement resulted from European colonial land grabs that set the foundations for settler agricultural economies.

Among these groups, localized historical narratives of colonial injustice have molded the discursive lens by which citizens frame their past and present grievances. Under new democratic dispensations, institutions that help catalyze redress are now within the reach of citizens who have over the years agitated for compensation. But these bids come in the context of an increasingly commercial agricultural sphere, where fragile economies rely on the secure tenure of profit-maximizing, large, foreign-owned farms. What then happens when moves for reparations threaten such large-scale agricultural ventures, as is the case currently in Kenya?

Kenya���s land inequalities stem from its initial settlement by the British. To make room for white settlers in the late 19th century, the British colonial administration bestowed upon the Crown the power to control and alienate land in the Protectorate. Colonial administrators dispossessed some of Kenya���s most populous communities, including the Kalenjin, Maasai, Kikuyu and Luhya of much of their high altitude and fertile arable or grazing land, often through violent means. The Kipsigis of the South Rift were especially affected. According to our calculations, in the 1920s the former Kericho District (which was much larger and more multiethnic than it is today), had 1600km2 of land (or 33 percent of its land) declared for white farming only, including large tracts for British tea companies like Brooke Bond and Finlays. When the Talai clan of the Kipsigis resisted, the British jailed and exiled their leaders. Under the 1934 Laibons Removal Act, the British exiled the entire Talai clan���estimated at 750 people���to camps in the far away and inhospitable Gwassi region of Kenya.

Upon Kenya���s independence, the government of Jomo Kenyatta was tasked with the redistribution of most of the individual farms that made up its infamous “European Highlands.” But large agricultural estates like Kericho���s tea estates���now held by multinationals���remained on 999-year leases which they had originally been granted by the colonial government. A majority of the leases remained unaffected post-independence. The estates have now emerged at the forefront of legislation and bids to claim rights and reparations for dispossessed communities.

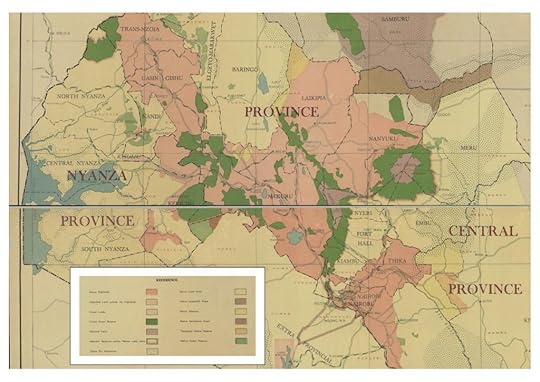

Excerpt from Director of Surveys Map ���Kenya-Political and General,��� 1951, showing the old Kericho District. The areas in pink were alienated for white settlement only.

Excerpt from Director of Surveys Map ���Kenya-Political and General,��� 1951, showing the old Kericho District. The areas in pink were alienated for white settlement only.The Constitution now provides the requisite institutional infrastructure for redressing of unresolved injustices through the creation of the National Land Commission (NLC), the shortening of the colonial era leases to 99 years and the strengthening of new local governments at the county level. After 2010, Kenya���s institutions were very much in flux, with new actors and a new dispensation that has shaped and informed the strategies adopted in the claims against the colonial government and the tea multinationals before the NLC. By raising their claims in the county assembly in 2014 and filing them at the NLC in 2017 and 2018, the Kipsigis and Talai clans took advantage of these crucial openings. Simultaneously, the fledgling institutions of the NLC and the county government have found initial legitimacy in taking on cases like the tea estate claims of the Kipsigis and its Talai clan. In dealing with these claims, the two institutions, particularly the NLC, reconnect with Kenya���s constitutional history and Kenyans��� long-standing demands for land restitution.

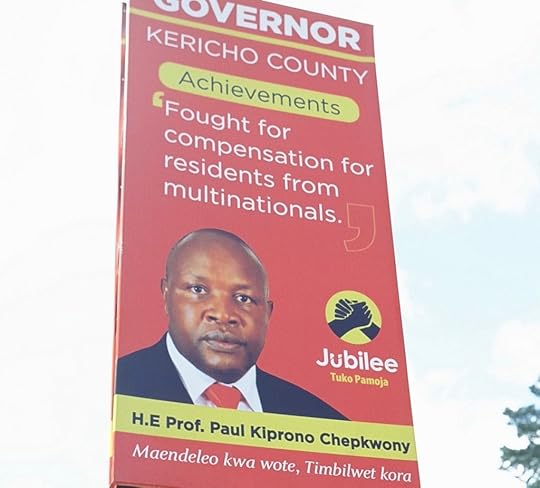

The claims made in the tea estate case rest on a number of axes: dispossession of land by the British, the forced removal of the Talai clan, issues around taxation in the tea estates, and unfair competition in the tea sector between the large multinational estates and smallholder tea farmers in the region. Kenya���s new county governments have provided a platform to push these grievances. Paul Chepkwony won the first election for Kericho���s governor in 2013 on a campaign to restore the tea estates to the community. Resting on his campaign on the tea estates, Chepkwony survived a top-down party attempt to remove him through an impeachment bid in 2014 and then won the 2017 nomination and election.

The tea estates are now a powerful election tool for local politicians to find actionable local grievances. In the neighboring Nandi County, the battle for control of local politics has similarly shifted to the tea estates where the county governor has led locals in “reclaiming” land “grabbed” by tea multinationals. Coverage of the Kericho tea estates bid has been mixed. Some outlets, like AFP and The Guardian, attempt to interview claimants and to accurately represent these complex and historical claims on past and present injustices. Others warn that bids should be wary of harming productive, large farms and the local economy.

A Member of County Assembly tables a motion in Kericho in 2014. Credit Alex Dyzenhaus.

A Member of County Assembly tables a motion in Kericho in 2014. Credit Alex Dyzenhaus.Still some, like this Economist writer, seem to align themselves with the multinationals, calling the demands of the Kipsigis “preposterous” and “implausible” and implying that they will impede local development and investment or even lead to violence. Much reporting focuses only on the worst possible economic implications if their claims are successful. A Telegraph article leads by comparing the tea estate claims to “Zimbabwe-style land grabs,” emphasizing the possibility of severe tea shortages in Britain. This sentiment rippled through the media, with less reputable sources like the Daily Mail and Sputnik News articles repeating the claim that Zimbabwe style land grabs are on the agenda.

Such accounts downplay the many times that Chepkwony has committed himself to working within the law to reclaim land and even electing to pursue the claims through the constitutionally established NLC. Through the media, the multinationals have made concerted efforts to spin the narrative and present the claims as a bid for the profit of politicians at the expense of the profitable tea sector. Such selective readings may set the tone for how the NLC responds to these claims.

A similar logic has been advanced by another multi-national, Del Monte Kenya Ltd, whose operations in Kiambu and Muranga counties have been threatened by claims from dispossessed local groups. Del Monte has argued that digging up the past will lead to loss of revenue, local corruption and renewed conflict.

An election poster for Chepkwony reads: Development for all, re-elect Timbelwet. Chepkwony���s nickname Timbelwet comes from the old name of the contemporary Tea Estate his family called home before Colonialism. Credit Alex Dyzenhaus.

An election poster for Chepkwony reads: Development for all, re-elect Timbelwet. Chepkwony���s nickname Timbelwet comes from the old name of the contemporary Tea Estate his family called home before Colonialism. Credit Alex Dyzenhaus.In Kericho, Chepkwony has undoubtedly used the claims as a concrete election tool to help him win elections, but he has made the issue about more than just regaining unjustly confiscated land or colonial injustice. He has also brought up the issues of increasing government revenue through taxing large multinationals and creating fairer terms of trade for small holders in the region. In an electoral context where many assume that politics is about patronage and corruption, the tea estate-related package of reforms is a clear instance of a popular and multilayered programmatic appeal to voters that targets the needs of farmers and government with a vision for a more equitable future.

In the politics of land in Kenya, there is always a risk that politicians can capture resources, and by allowing the political elite to shape claims and narratives of injustice, communities run the risk of subjecting their claims to political manipulation and opportunism. Equally, politicians can amplify claims by local communities and enable them access for the redress of grievances. This can be done where communities are provided with institutions that facilitate their mobilization and which enable them to effectively articulate their causes.

And while critics may spread fear through claiming “threats of violence” and arguing that these demands are unreasonable, in doing so they willfully turn a blind eye to the fact that the claims are proceeding through clear legal and democratic pathways. In an age where large scale land deals for agricultural and mineral rich land bring investment via dispossession and displacement, international observers should laud and assist efforts by local politicians like Chepkwony and institutions like the NLC to think through these issues carefully, legally and peacefully.

Land restitution is not about digging up the past at the expense of the present. Instead, it is about investigating the past to determine how to most fairly allocate wealth and profits today. This is true both for the tea estates but also for new deals that would allow large companies to extract minerals and farm agriculturally rich land across Africa and the rest of the world.

Vanquisher of troubles or light of our home

Screenshot from YouTube.

Albalabel, a Sudanese girl group comprised of three sisters, came to prominence in the late 1960s and gained national acclaim in the wake of Mohamad Jaffar���s Nimeiri���s leftist and bloodless coup of May 1969. The coup toppled an elected prime minister and set in motion a 14-year military reign. There was widespread support for Nimeiri because of his promises to tackle the economic malaise and bring peace. Nimeiri introduced massive economic and political reforms, but also, crucially, supported the creative arts.

Early achievements of the Mayo uprising, as it was fondly called by the Sudanese, included the Addis Ababa peace agreement of 1972 which ended the north-south civil war, for a time. However, the ideals to forge peace with the marginalized south of the country, nationalize industries and promote a secular politics quickly unraveled amid internecine intrigues within the ranks of the revolutionaries as well as opposition from more conservative and sectarian political forces.

The coup ushered a cultural renaissance of sorts. Many artists composed revolutionary songs celebrating the new regime and its ideals. Most famous among the songs of Mayo is Albalabel���s ���Ab Aaj,��� a praise song for Nimeri. ���Ab Aj��� valorized the president and the lyrics to this day are synonymous in the Sudanese imagination with Nimeiri. The opening verse proclaims, ���The girls ululated and the people hailed you as their leader, oh ivory clad brother, vanquisher of troubles.��� The song was a hit, one of Mayo���s greatest anthems.

By 1983 the north/south civil war had resumed. Nimeiri, in order to shore up his waning hold on power had long abandoned secular governance and embraced the political Islam curriculum of the Muslim brotherhood.

Much of Albalabel���s repertoire focuses on more domestic and everyday trials and joys. ���Usha sagheera,��� (a small nest), is a ballad of sorts, where a young woman reassures her beloved that she would be content with a small nest, a modest home. Albalabel���s songs were of their time and seem bittersweet from our vantage point in the 21st century. The reality is that even a small nest is no longer sustainable financially. From the late 1970s to this day many Sudanese men have had to leave their wives and children back home and work abroad in order to provide for their families.

Albalabel were a phenomenon in their time because their music felt and sounded innovative, marking a departure from the patriotic and nationalistic songs of Alhageeba, the songs celebrating Sudan���s emergence from British colonialism. Their musical output also departed from the vernacular daluka songs that were part of a tradition of orally transmitted songs performed by women singers at weddings. Their creativity and innovation was in the compositional arrangements of their music, which not only borrowed from the traditional orally transmitted Sudanese daluka and praise songs, but also integrated lyrics about the lives of urban women to create a unique new sound.

Albalabel were adept at negotiating and, at times, pushing the boundaries between the traditional and the progressive in what was and is a deeply conservative and patriarchal society. A significant factor in their acceptability to conservative audiences was that their manager was also their father, a forward thinking and dynamic high school principal. The subliminal message was that these are not rebellious girls seeking emancipation, but that their father was backing them and overseeing their activities.

Nevertheless, as young female performers Albalabel pushed boundaries creatively in their music as well as culturally. For example, while hijab (the Muslim head covering for women) was not as common a phenomenon as it is now, most young women used to loosely drape a tarha���a light, white cotton scarf���around their head and shoulders. The Balabel sisters did away with this garment altogether. They were a sensation and trend setters, young women around the country copied their hair styles. Following every TV appearance by the girl band, fashion savvy young women hastened to their tailors with yards of cloth requesting the Balabel style. (This was the time before globalization and mass off-the-shelf fashion, a time when artisanal dressmakers could make a living handmaking dresses). Albalabel���s youthful energy and their music was a reflection of a 1960s and 1970s Sudan, where liberal and secular principles were embraced by significant swathes of the public. The Sudanese are deeply devout but faith for the most part then was a personal endeavor.

Albalabel were somewhat eclipsed during Omar Al Bashier���s Ingaz regime. In the early phase of the regime, 1989 to 2000, religious and patriotic anthems gained prominence. In the latter phase, the regime began to relax its strict Islamist codes and new, younger solo artists including women artists like Nada Algala and Haram Alnour rose to prominence. In the wake of the December 2018 uprising that toppled Albashir Albalabel, the three sisters are still together, still beautiful and strong women, now in late middle age but sounding as they did then. Sudanese audiences responded to them enthusiastically, as though running through Albalabel���s music was a call and response between the sentiments and hopes of May 1969 and December 2018.

When Abdallah Hamdok, the Sudanese world bank economist who was ushered in as interim prime minister in the wake of the Sudanese people���s stand for freedom, peace and justice visited Washington in early December 2019, the Sudanese diaspora serenaded him with a Balabel song. They chose, ���Nawar beitna,��� light of our home, a sweet song about an adored male relative, family friend or prospective bridegroom who stops by for a surprise visit. Hamdok was greeted with the verses, ���Our house lit up and our street lit up the day you stopped by.��� The Sudanese diaspora in Washington���s serenading of the prime minister was no doubt an act of nostalgia for the music of their homeland. But, the choice of song also speaks to the cautious hope they invest in the Prime Minister and in the caretakers of the December 2018 uprising as a whole. Some of the older members among that diaspora audience would know firsthand the cost of a revolution coming undone. Theirs is a far cry from the hero worship of the ivory clad, vanquisher of troubles of 1969. Nimeiri was a military man who dealt ruthlessly and bluntly with dissent among his own allies as well as among the sectarian political parties opposing him. He chose to eliminate all who stood in his way. By turning to the Muslim Brotherhood in order to maintain his hold on power, Nimeri had paved the way for Al Bashir���s Islamist regime.

The predisposition for failure and derailment is as potent for Hamdouk as it was for Nimeiri: a fractured military vying for power, sectarian forces unwilling to update their governing structures or modify their commitment to political Islam, discontent and armed rebellion in Sudan���s marginalised Nuba Mountains and Darfur, and economic collapse. A military man like Nimeri ultimately failed to govern, to forge a stable unity out of Sudan���s contradictions and fault lines without violence. Rather than vanquisher of troubles, Hamdouk is soberly, modestly hailed as a light, a hope. Could Hamdouk, the man of intellect, of civil governance navigate those same fault lines and tame the contradictions with the nuance and balance that allows for Sudan���s competing forces to find expression within a stable whole?

An overlooked pillar in the art of governance is perhaps the role of the arts and music���not as externally imposed propaganda, but as an act of listening to the vernacular hopes and sentiments of a people. Hamdok would do well to harness and nurture the role of the arts and in particular the role of music in his and our project of imagining a better Sudan.

February 1, 2020

Reading List: Ainehi Edoro

Young girls using their mobile phone in rural Makurdi, Benue state. Image credit Kristian Buus via Stars Foundation Flickr CC.

Yrsa Daley-Ward is the people���s poet. After a career in modeling, she turned to writing. She is well-known on Instagram where she writes those lovely little things called Instapoetry. The Terrible is her third book, a memoir told in an elegant ensemble of prose, poetry, and everything in between. Her stories about childhood are intimate and honest. Nothing is left out. All her vulnerabilities as the one black child in an all-white school, as a pre-pubescent girl living with her mother���s erratic boyfriend, as a child growing up with religious grandparents, as girl with an awkward body, who becomes the young women spiraling down the rabbit hole of drugs and alcohol. We are all programmed to recall our childhood through filters of complicated emotions. This book does an amazing job of creating art and poetry from this fact of life.

Critique of Black Reason by Achille Mbembe: Critique of Black Reason is a genealogical project in the Nietzschean sense of term. It allows us to take a peek at the moments in the European archive when Africa is being constructed as black, and blackness is being assigned to the space of madness and delirium. Mbembe writes: ���By granting skin and color the status of fiction based on biology, the Euro-American world in particular has made blackness and race two sides of a single coin, two sides of a codified madness.��� The book traces a direct link between the invention of blackness as racial other and the rise of capitalism. Mbembe has written a really special book that, in many ways, recalls the success of On the Postcolony.

Blind Spot by Teju Cole: Blind Spot is a beautiful book, but for the oddest reason imaginable: it inventories a nonsensical cluster of things. The 150 pictures in the collection depict a raft of unremarkable things: curtain folds, an abandoned bath tub, a pair of scissors, the back of a leather couch, tire marks on mud, a decaying boat, a mail box, folding chairs, cement, a bus stop, a car, wall paper, hand bags, a dog, a bush, a mannequin, and so on. When we focus on these scattered bits of very ordinary things, we realize that the moments captured in Cole���s photographs are incomplete moments, splinters of life���s fragmented realities. The images stand in their haunting incompleteness without asking to be improved upon, explained, or made whole. They reveal very little. They are pedestrian. No spectacle to look at. But, in saying so little they convince us that they are hiding a secret truth, for, as Nigerian fantasist D.O. Fagunwa suggests, in a 1960 essay, images become interesting the moment they stop explaining themselves.

Black Leopard Red Wolf by Marlon James: The first line of the novel gives away the ending. ���The child is dead. There is nothing left to know.��� The more than 500 pages that follow explore the intrigues surrounding the boy���s identity and the motivations of those who want him either dead, found, or alive. Black Leopard Red Wolf is a meticulously crafted world of cities, libraries, trade routes, desert travel, sea ports, enchanted forests, dark, twisted characters and political intrigues���an African medieval world essentially. Drawing from Amos Tutuola, Ben Okri, African epics, the Timbuktu archives, and medievalist fantasy like Game of Thrones, James re-imagines the African past in a radically new way.

Broken Places and Outer Spaces by Nnedi Okorafor: Like most good stories, Okorafor���s story of transformation from pre-med student to Africanfuturist writer is the result of the unexpected. In the book, she credits her decision to pursue writing to an event she simply refers to as ���the breaking.��� After her first year in college, a spinal fusion surgery left her paralyzed from the waist down. The memoir starts out as a very intimate account of utter vulnerability and ends up an epic discovery of a creative universe. But as Soyinka reminds us in his essay ���The Fourth Stage,��� epic stories about world-making begin from tragic experiences. Or as the title of the memoir suggests, the discovery of outer spaces begins from the experience of broken places. The book is special because it gives a rare insight into Okorafor���s creative philosophy. It is an artist opening up about the difficult journey into creative becoming.

January 31, 2020

An indispensable figure of African photography

Santu Mofokeng's ���Easter Sunday Church Service,��� from Chasing Shadows (The Walther Collection).

After a long illness, Santu Mofokeng, a major figure of photography in South Africa, passed on January 26th 2020. He has been eulogized on social media in loving tributes by close friends and family. These tributes have shown him as a leader in his community, as well as within the family of visual artists and art practitioners, not only in South Africa but across various centers in the world. His now iconic photographs circulate the internet in the wake of his passing. We recall an incredibly influential, and indispensable figure of African photography.

Born Ntate Santu Mofokeng in 1956, he was raised in Soweto, the large township to the south of central Johannesburg. He was also educated in there, and grew up in the early days of legalized apartheid in South Africa. The official policy of racial segregation was made constitutional in 1948, and only declared void in the early 1990s. He was undeniably inspired by a broader visual black culture before, during and after apartheid. He was inspired by the traditional spiritual and linguistic cultures of black South Africans, and their photographic practices in the Victorian period. His work challenged the legal construction of blackness in law by following quotidian black life in Soweto, among many places.

“Eyes-wide-shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens” (The Walther Collection).

“Eyes-wide-shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens” (The Walther Collection).While Mofokeng was arguable a pioneer, many artists in South Africa had depicted urban black life. These include the painters David Koloane, John Koenakeefe Mohl, Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi, Gladys Mgudlandlu, and the photographer Ernest Cole, alongside novelists such as Es���kia Mphahlele and Mariam Tlali. In this sense, his work is part of a history of art in the country made of refusals to conform to official or legal constructions of blackness. A history of artists that stubbornly pursued beauty in the midst of political and social malaise. Thus, how is the photographer and writer to be remembered?

Lekgetho Makola, director of Market Photo Workshop���which recently established the Santu Mofokeng Fellowship���emphasized his role as an artist and thinker ���involved in the writing groups of the 1970s in Soweto during the rise of Black Consciousness thought among many youths then in the Townships of South Africa. He left us with his compelling and critically positioned consciousness in his images and text.��� Elaborating on his model of thought, Gabi Ngcobo, international curator who previously worked on the 10th Berlin Biennial of Contemporary Art, said, ���his philosophy was based on making instead of taking photographs; a philosophy that I understand as an extension or continuous journey towards our personal and collective freedoms, both imagined and real.���

“Dove Lady #4, Orlando East, Soweto,” 2002. From the series Billboards (The Santu Mofokeng Foundation).

“Dove Lady #4, Orlando East, Soweto,” 2002. From the series Billboards (The Santu Mofokeng Foundation).Tumelo Mosaka, South African curator based in New York, said he was ���a complicated and dynamic photographer whose poetic images and short stories captured eloquently the ongoing human struggle against existing inequalities,��� while Emmanuel Iduma, Nigerian art critic, said his work was ���a complete education in looking.��� Similarly, John Fleetwood, notable curator of African photography, said he reminded us that ���photography is a method of thinking.���

Before the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie turned readers onto the ���dangers of a single story,��� Santu Mofokeng had taken up the mission to tell stories of black life that did not conform to the stereotypical agendas of news media. In a 2010 interview published in the African Cities Reader, he said, ���I was never into victimology���I decided to do a project that is kind of a fictional biography or a metaphorical biography,��� adding that, ���I go to shebeens, I play football, not necessarily as a kind of lack but to show it for what it is.��� In his disobedience to the trend of ���victimology,��� he took a radical approach to photography that advocated the complexity of aesthetic and spiritual dimensions of black life.

This philosophy is evident in two photographic series, Train Church, and The Black Photo Album / Look At Me (1890-1950). Writing on the earlier series that he started in 1986, he depicted his own observations of the everyday: ���You arrive on Monday, you just want to sleep at two in the morning, you have been jolling, you���re hoping when you arrive in the train you can get some sleep ��� Two stations down the church begins and people start clapping hands and sing hymns, and then you find yourself in church��� (2010).

“Buddhist retreat near Pietermaritzburg, Kwazulu-Natal” (Lunetta, Bartz, Maker, Johannesburg).

“Buddhist retreat near Pietermaritzburg, Kwazulu-Natal” (Lunetta, Bartz, Maker, Johannesburg).Then, writing on the latter series which is a collection of personal photographs commissioned by black South Africans in the Victorian period he considered the idea of self-representation: ���When we look at them we believe them, for they tell us a little about how these people imagined themselves��� (1998). His shimmering and multifaceted black and white photographs drew attention to multifaceted stories, and experiences, ignored, if not disputed by the mainstream.

Santu Mofokeng���s career, which spanned decades, began in Soweto, where he practiced street photography. In 1985, he would establish the Afrapix Collective, alongside photographer Omar Badsha, among others. He would go on to work as a technician developing photography in the dark room, before being hired as staff photographer at the New Nation newspaper in 1987. Shortly thereafter he began working with the University of Witwatersrand as a researcher.

His renown international career came in the 1990s, with local exhibitions at the Second Johannesburg Biennial, and international group shows in Bamako, Mali, such as the first and second editions of the Bamako Encounters-African Biennial of Photography, and the S��o Paulo Biennial and Documenta 11, Kassel, both in 2002. Additionally, he had a retrospective solo exhibition at the renowned London photography center Autograph ABP in 2009, and received the prestigious Ernest Cole award at the International Center for Photography in New York.

Santu Mofokeng is survived by his wife Boitumelo and their two children.

January 30, 2020

The Salah effect

Sadio Man�� at Liverpool vs. Chelsea, UEFA Super Cup. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

For many people around the globe, the weekend means football. We gather around the TV, awaiting new miracles and heroes. Talking about religion and football in the same breath seems only natural; for many football supporters, their team is more important than just about anything. The stadium is their cathedral, their club’s songs providing them goose bumps and a sense of community. The football shirts and scarves are proud symbols of belonging. An unexpected match win is a “miracle,” and decisive goals, rescues or tackles produce “saviors” never to be forgotten by the faithful fans.

The relationship between religion and football is multifaceted but also explicit, not just as a metaphor. In arguably the world’s most important football league, the Premier League, Islam has come into focus, although in a different way than elsewhere in the European media. We have become used to watching Christian footballers crossing themselves, or pointing to the heavens after a goal. Or born again Brazilians in t-shirts that say “I belong to Jesus��� (the Brazilian Kak��) or headbands saying “100% Jesus” (his countryman, Neymar). Just last week another Brazilian, Roberto Firmino (Liverpool) posted his Christian baptism ceremony on his Instagram, saying ���My biggest title is Your love, Jesus!��� The Brazilians football players are, as their fellow compatriots, increasingly evangelical, known for their emotional, expressive and politically conservative form of Christianity.

But with players like Mohamed Salah and Sadio Man�� (both Liverpool), N���Golo Kant�� (Chelsea), Paul Pogba (Manchester United), Mezut ��zil, Granit Xhaka, Mohamed Elneny and Sead Kolasinac (all Arsenal), and Benjamin Mendy (Manchester City), Muslim practices have become visible in new and varied ways.

The brightest star of them all is Mohamed Salah. In 2019, he appeared on Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world. Time acknowledges Salah for being one of the world’s best football players, but at the same time praised him as a human being. To his fans and admirers, this ���Egyptian king��� is laid-back, respectful towards his opponents, joyful and charming, and he lives a ���simple life,��� compared to the other stars. He is married to a ���normal��� woman (i.e. not a model), and he’s a Muslim. Together with teammate Man��, he visits the local Liverpool mosque, he engages in charity work, and doesn’t drink alcohol. Salah’s distinctive way to celebrate goals���bowing to the ground���is also on display when the FIFA 2019 “Salah” celebrates a goal, bringing the praising of Allah to millions of gamers around the world.

Last year, a group of researchers from Stanford University published a study of what they call the “Salah effect” in Merseyside. They argued that Salah’s immense popularity helped reduce hostile attitudes towards Islam in different ways. Since 2017, when Salah signed to Liverpool FC, there has been less hate-motivated crime against Muslims in Merseyside. Liverpool fans are also less critical towards Islam on social media like Twitter. And one of the songs at Anfield, Liverpool���s ground, now goes like this: “If he scores another few, then I’ll be a Muslim too.���

Another Muslim role model, although more controversial, is Paul Pogba, who plays at Manchester United. This tall Frenchman’s flashy clothes, expensive haircuts and muscle flexing are arguably on par with Cristiano Ronaldo of Juventus. Pogba is married to a Bolivian photo model, and his 39 million (!) followers on Instagram are being treated to family photos where everyone is dressed up in all-Versace outfits. At the same time, Pogba has shared pictures of his pilgrimages to Mecca and of himself immersed in prayer. Last year, from Mecca, with a Gucci bum bag hanging fashionably over his shoulder, and posing in front of the Kaaba, the center of Mecca���s Great Mosque, he urged his Instagram-followers to “never forget the important things in life.”

Pogba, Salah and other Muslim superstars are known as football players, not Muslims. They come from different countries���from Egypt, Senegal, Turkey, Germany, Switzerland, and France. In a European context, where the cultural and political soundtrack has become increasingly anti-Muslim, these super star role models make a difference. Whether the “Salah effect” remains if Salah changes clubs or stops scoring goals is uncertain. In Europe, having a minority identity might be positive as long as everything is going well, but could be negative when things turn sour. Mehmut ��zil (Arsenal), left the German national team because of racism, claiming that for many people he was “a German when we win, an immigrant when we lose.��� Players with minority backgrounds from the national teams of Belgium and France share similar stories. But for the many Muslims in England and around the world, the new stars���from Salah to Pogba���clearly demonstrate that there are many ways to be a Muslim, also in the public.

Roti and roses

Zohran Mamdani. Image supplied by Mamdani.

In 2018, a socialist bartender from the Bronx named Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez shocked everyone (even herself) by unseating the 5th-highest ranked Democrat in the United States House of Representatives. The secret to her success was a relentless ���ground-game������hundreds of volunteers who knocked on doors, made calls, and generally pounded the pavement in her district, which covers part of the Bronx and a big chunk of northern Queens, New York. Many of those volunteers were mobilized by the New York City Democratic Socialists of America, or DSA. The DSA has been around in one form or another since the early 1970s, but it became a force to be reckoned with after the 2016 election, when thousands of people, galvanized by Bernie Sanders��� 2016 bid and angered by Donald Trump���s win, began flocking to the organization. (With fewer than 7,000 members in May 2016, DSA membership now exceeds 55,000, with more than 180 local branches nationwide). Since then, it has helped propel socialist candidates to national (Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan) as well as state-level elected offices. A recent show of muscle was again in New York City, where it brought a queer, Latinx, socialist public defender named Tiffany Cab��n just 55 votes short of defeating a machine politician in the Democratic primary for District Attorney of Queens. Now that same New York City DSA chapter is putting its weight behind a ���squad��� of candidates for statewide office. One of those candidates is the Ugandan-born and partly South African-raised Zohran Kwame Mamdani.

Mamdani, whose parents happen to be the prominent Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani and Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair, is a 28 year old rapper and foreclosure-prevention counselor running for New York State Assembly. Below is his conversation with William Shoki, a staff writer at Africa Is a Country, about identity and class, running for office, and what it means to run as a socialist in America.

William Shoki

How long have you been in New York City?

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

We moved to New York City when I was seven, so it���s coming to twenty-one years now. We actually moved from Cape Town. I was born and raised in Kampala, and we moved to Cape Town when I was about five and lived there for two years. Between birth and getting to five, there were a few months where my dad worked in Durban so we lived there for a little bit. In 1999 we moved to New York, and I���ve been there since. So, this is definitely home for me.

William Shoki

Do you ever go back to Uganda? One of the reasons I���m interested is that my parents are East African, but I was born and raised in South Africa. As much as I am South African and identify as a Joburger, it���s still for some reason difficult to part with the Tanzanian identity. Even though I don���t spend much time there, nor do I have a foothold there in terms of what my plans are for the immediate future, I nonetheless call myself a ���Tanzanian South African.��� So it���s a strange, diasporic identity I haven���t made sense of yet.

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

It���s definitely a complex journey because I am many different things all at once. There���s no question in my mind that I���m Ugandan. There���s no question in my mind that I���m Indian. And there���s no question in my mind that I���m a New Yorker. And I���m all of these things, yet in each of these places I���ve been made to feel that it���s not actually my home to call��� in Uganda, I���m told this guy is actually Indian, in India, I���m told this guy is actually Muslim, and in New York I���m everything but a New Yorker.

But I���m realizing that it���s not a determination I should be outsourcing to others. It���s something that if I know and feel, then I need to become comfortable in asserting. Others will take time in catching up to that. It also helps to understand that if you���re part of any diaspora you have to live in multiple worlds at once, and have multiple sets of cultural references and histories���so that if you were to describe yourself in one singular term, it doesn���t really capture the different ways in which you think about the world.

Mamdani canvassing in Queens, NY. Supplied by Mamdani.

Mamdani canvassing in Queens, NY. Supplied by Mamdani.William Shoki

What do you think this perspective does for your campaign?

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

When I was a kid I used to struggle with the experience of always being a minority. Not only national heritage, but even religious heritage���not only am I Muslim, but I���m also Shia, not Sunni. And my father would tell me that it���s not something to face anguish about, because when you���re a minority you are constantly seeing the truth of the place. You���re not lulled into the promise that is fed to everyone about how perfect and pure society is, because you���ve constantly been made to feel the exceptions, you���re constantly having to go through the ���terms and conditions��� of that promise.

The way in which it informs our run for Assembly in New York State, is that, if you���re always on the outside then you have an understanding of the flaws of this society in a way that someone on the inside might not have had to grapple with personally. I don���t think that representation in and of itself is enough to deliver us to the world that we need, I think it���s a part of it. The real, key power of representation is that you not only look like someone who hasn���t been at the table, but that you in fact change the nature of which discussions are prioritized, and that you���re fighting for a different set of priorities that have been ignored. Arundhati Roy has spoken of the idea that, ���there are no voiceless people, there���s just the unheard.���

So many communities in New York City and State have been speaking for decades but have simply been ignored. When you think about New York City, South Asians are a rich part of this city���s history and cultural fabric, and yet there has been no representation of South Asians at a legislative level��� never has a New Yorker of South Asian origin been elected, at any level. Whether it���s the level of a city-council person, or a Congressperson, or a State senator or whoever it may be��� and yet there are more than 330,000 South Asians. We have more than 750,000 Muslims, but there���s only one Muslim in the entire 150 person body of the New York State Assembly.

And it���s not simply that people don���t look like us, but that the issues that disproportionately affect these communities are not being discussed with the emphasis and importance that they should be. 40% of New York City cab drivers are South Asian. More than 50% of street vendors are South Asian. Around 38% of all New York City public school students, are either Muslim or Jewish, and yet there���s religiously permissible food is hard to come by in New York City public schools, and New York State public schools.

These issues for most people don���t seem like the most critical ones to fight for. But a Muslim kid whose parents are unable to pack them lunch every day is in effect being forced to choose between eating and what they believe in. So it becomes a matter of hunger for food or hunger for faith��� pick which hunger you���re going to be dealing with for the rest of the day.

William Shoki

You���re campaigning in a borough that���s said to be one of the most diverse in the United States. As much as you���re sensitive to the importance of representation for different identities, the platform you bring emphasizes a common struggle to New Yorkers in the housing precarity they face. Why do you think this is a unifying struggle, is that even important to begin with?

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

A unifying struggle is critical because for so long, what we���ve been told are oppositional forces are in fact facing the same issues as we are���the true cause of the issue, the true set of actors benefiting from the status quo are not named in the discussion.

For example, in New York City and New York State, we have a massive housing crisis. More than a 100,000 New Yorkers are estimated to be homeless at this time. For a quarter of Astoria residents, half of their income goes to rent���and I���m one of those residents. For a long time, people said if you���re pro-tenant, you���re anti-home owner, and vice versa. And I work as a foreclosure prevention housing counselor, I work with low income homeowners. What I���ve seen in my work is, it���s not tenant versus homeowner. Really, what it is, is tenant and homeowner versus financial speculator and investment bank portfolio.

We have seen the takeover of neighborhoods that used to be the landing ground for immigrants new to this country trying to build a life for themselves and their families. Now, so many of those homes are being bought up by unnamed investors in the form of limited liability corporations, and now a third of the purchases in multiple neighborhoods are by these kinds of entities instead of families. We need to reassert that the importance of a home is what it provides a family, not what it provides a bank account and a bank balance.

Homes should not be a place of financial speculation, they should be a place of stability and setting a foundation for a family to build on for the rest of their lives. This is not the only issue we care about, but the reason it���s a flagship issue is that it���s a building block of the major crisis facing New Yorkers across all communities. Everybody is facing this, but if you���re a South Asian immigrant and you don���t speak English, then all of a sudden the crisis takes on a different dimension where you cannot even access the services that exist to alleviate this kind of issue.

If you are a Black New Yorker seeking housing, you don���t simply have to deal with the rising rents, but you also have to deal with the racism of landlords who don���t want Black tenants. These things are amplified by the ways in which racism and anti-immigrant bias function in our society. That���s why our slogan is ���Roti and Roses,��� building off the labor chant of the early twentieth century in Massachusetts where they said they were fighting for ���Bread and Roses������ for that which is necessary to survive, and that which is necessary to thrive. We call it Roti and not bread to make clear that while this is a universal cause, we���re also making sure to highlight the struggles of specific communities that have been left out in the cold for decades.

William Shoki

Why then, is it important in District 36, Queens and New York generally, to be more than a progressive legislator who���s alive to the cultural dimension of these struggles, but an avowed democratic socialist as well?

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

To be a democratic socialist means that you are committed to the state providing for people that which is necessary to live a dignified life. Because if you are dedicated to that vision of a society, and that is your true aim as a legislator and organizer, then you are far more willing to go up against the powers that be that will throw obstacles in your way.

Let me be clear, for us to succeed we have to do it with allies from across the ideological spectrum��� there are many fights where democratic socialists and self-described progressives will be on the exact same side. There are times though, when there will be division and you always need organizers who are willing to expand the political imagination beyond what is considered acceptable.

What was so appealing about becoming a self-avowed democratic socialist and a member of the DSA in New York City is their willingness to take on things which are seen as beyond the pale. I began my political organizing life around Palestinian solidarity, I co-founded my school���s Students for Justice in Palestine��� and on that issue especially in New York, a lot of progressives are ���Progressive Except Palestine.��� But when I got to a DSA meeting, I find that there is nothing beyond the pale.

What we are fighting for is a world that provides these things for everyone, regardless of whether they live–under occupation or if they are right here in District 36 in Astoria. We are fighting for equity and equality. For too long people have been afraid to call things as they are, and it���s been such a beautiful experience to fight alongside people who do not flinch when we describe [the situation in Israel/Palestine] as Apartheid because of the actual conditions demanding to be called as such.

Mamdani speaking at a Masjid in his district. Supplied by Mamdani.

Mamdani speaking at a Masjid in his district. Supplied by Mamdani.William Shoki

Your multi-cultural heritage is something that is increasingly shared by many leading American progressives occupying the highest levels of office, such as Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib. Do you think your background places you in a position where, as these two congresswomen do, you can speak more forcefully on foreign policy issues or does that overstate what your unique identity allows you to do?

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

My identity has informed my understanding of the world. There will be those that have the exact same identity but have a different understanding of the world, which goes back to the point on representation and how you have to build upon more than just that. But from my experience, you cannot ignore the things that you have seen.

When you are from the places where I am from, being Ugandan and being Indian, you see what this country has done from a very different perspective. In Kampala, the average perception of so many things in terms of the world around us is radically different from what we are fed in the United States. Bringing that perspective to the discussions here is critical, because if you simply have an inward facing discussion while the policies you���re debating will impact the world at large, it does a disservice to everyone and has grave consequences.

It���s so exciting to see people like Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar being on the national stage and reframing the discussions on both American foreign policy and American domestic policy, but how the state is structured and who it benefits, because it changes what is possible.

For so long, if you had certain views you were made to think you had no place in this country���s civic and political life. What these women have done, and many women before them, is to make clear that our place is not only here but our time is now, and it���s our job to struggle in public around these issues, because what the opposition would love us to do is be silent and discuss them only in private.

Mamdani and other candidates and organizers of NY Homes Guarantee. Image credit Divya Sundaram.

Mamdani and other candidates and organizers of NY Homes Guarantee. Image credit Divya Sundaram.William Shoki

As a final question, the places you hail from, and honestly the world at large, are experiencing political breakdown with significant and far-reaching problems. In Uganda, President Museveni���s bid to run for a sixth term has sparked a popular resistance to that, and in India, Prime Minister Modi���s Hindu Nationalism is oppressing Muslims with new intensity. One of the cornerstones of socialist politics of course is building a left-wing internationalism. What is the role of the DSA in that, given its rise to prominence as an insurgent socialist movement in a country that���s been so obstructive to that throughout history, which makes it exciting and inspiring to many people across the world, including me.

Zohran��Kwame Mamdani

We need to make clear that our commitment to these ideals is not restricted by borders, it is a universal commitment. One of the major things that appealed to me about the organization was its clear stance in favor of BDS. We have to make that commitment clear, but also need to first focus on how to stop the ways in which this country is harming the world through the continuation of decades of failed and extremely horrific foreign policy that has cost hundreds of thousands of lives across the world and overthrown more democratically elected governments than I can count.

Once that is achieved, next is to figure out how to act in solidarity with other socialist movements, other movements fighting for the working class across the world. We cannot fight fascism alone, we cannot do it on a country by country basis. We have to do so in a way that amplifies the work that allies are doing across borders.

When I look at each country I���m from and see that each of them is run by Museveni, Modi and Trump, it���s very easy to feel defeated. But the reality is that it shows us the commonality of the experience that people in this world are facing today, and as much as it���s terrifying there���s also this promise of a world that we could actually create together evident in the protests taking place. People are fighting back not merely to return to the past but to create a new future, and that���s very exciting.

January 29, 2020

Queering pan-Africanism

Screengrab from 'Rafiki.'

The recent politicization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) identities and rights in many parts of Africa has given rise to a renewed emergence of pan-Africanist thought in two directions. First, there is the well-known narrative of anti-queer pan-Africanism, invoked by many African statesmen, clergy and opinion leaders. It uses sexuality as a key site to defend and preserve African values and identities vis-��-vis perceived foreign imperialism. LGBT sexualities are framed here as ���un-African,��� and violence against sexual minorities is legitimized in the name of ���African pride.��� Ugandan human rights lawyer, Adrian Jjuuko, summarizes this as the ���rise of a conservative streak of pan-Africanism.��� Second, and of greater interest here, LGBT activists and allies across the continent resist this popular narrative through a discursive counter-strategy in which they deploy progressive black and pan-Africanist figures, ideas, and symbols.

One key example of this emerging discourse is the African LGBTI Manifesto, drafted at a meeting in Nairobi in April 2010 by activists from across the continent. It opens with a strong, explicitly pan-Africanist vision: ���As Africans, we all have infinite potential. We stand for an African revolution which encompasses the demand for a re-imagination of our lives outside neo-colonial categories of identity and power.��� The manifesto then explicitly states its specific concern with sexuality, but linking it to the project of “total liberation” of the African continent and its peoples: ���We are specifically committed to the transformation of the politics of sexuality in our contexts. As long as African LGBTI people are oppressed, the whole of Africa is oppressed.���

A similar emphasis on mainstreaming sexuality in a broader project of decolonization is found in the emerging body of literature in African queer studies. For instance, Sokari Ekine and Hakima Abbas state that ���at the root of queer resistance in Africa, is a carrying forward of the struggle for African liberation and self-determination.��� African queer politics is a project, not just concerned with LGBT identities and rights, but with the struggle against patriarchy, heteronormativity, homophobia, and neoliberal capitalism. It aims at a comprehensive liberation of African peoples and societies from the multiple structures of domination and oppression.

As much as the queer African project is about the future of the continent, there is a critical sense of retrieving something that has been lost in the course of history, and that can be recovered for contemporary political purposes. In the talk titled ���Conversations with Baba,��� the late Kenyan literary writer Binyavanga Wainaina uses an inclusive ���we��� to reclaim Africa as a continent that has always been characterized by diversity, and as such sets an example to the rest of the world: “We, the oldest and the most diverse continent there has been. We, where humanity came from. We, the moral reservoir of human diversity, human aid, human dignity.”

In Wainaina���s commentary, this rich and strong tradition of diversity characterizing African societies was only interrupted by “those people who came from that time of colonization to split us apart, until our splitting apart came from our own hearts.” Thus, he suggests that the interruption came from outside���from the forces of colonialism and missionary Christianity; he further suggests that moral conservatism and rigidity have been adopted and internalized by certain sections of society in postcolonial Africa, in particular conservative religious actors such as Pentecostal Christian pastors.

Vis-��-vis such forces, Wainaina calls for a reclaiming of indigenous African moral traditions that recognize human diversity. In part two of his six-part video, ���We Must Free Our Imaginations,��� Wainaina describes socio-political and religious homophobia in Africa as “the bankruptcy of a certain kind of imagination.” He urges fellow Africans to engage in creative, liberating, and imaginary thinking, reclaiming the past in order to reimagine the future���a future free from oppressive modes of thought.

In more popularized form, the same narrative is found in the “Same Love” music video. Released in 2016 by the Kenyan band Art Attack under the leadership of the openly gay musician and activist, George Barasa, the video was presented as “a Kenyan song about same sex rights, LGBT struggles, and civil liberties for all sexual orientations.” The lyrics and imagery present a progressive pan-Africanist vision, which unfolds in two steps. First, the video draws critical attention to the recent politics against homosexuality across the continent, showing newspapers with strong and sensationalist anti-gay messages and images of Kenyan anti-gay political protests. This part of the song concludes stating:

Homophobia is the new African culture / Everyone���s the police, Everyone���s a court judge, mob law, street justice / Kill ���em when you see ���em / Blame it on the west, never blame it on love, it���s un-African to try and show a brother some love.

In the next part, the lyrics specifically refer to Uganda and Nigeria, the two countries that in 2015 became internationally known for passing new anti-homosexuality legislation. Then the song calls upon Africa as a whole, saying:

Uganda stand strong, Nigeria, Africa, it���s time for new laws, not time for new wars / We come from the same God, cut from the same cord, share the same pain and share the same skin.

A positive pan-Africanist vision is presented here, emphasizing the unity and common history of African peoples. The basis for this vision is a religious one: the idea of African peoples as created by God. This echoes an important tradition of religiously inspired pan-Africanist thought, centering on the belief ���that Africa���s destiny is God given.��� In the words of Marcus Garvey: ���God Almighty created us all to be free.��� Originally, this religious notion allowed for resisting racial discrimination and overcoming the inferiority of people of African descent vis-��-vis white superiority. “Same Love” appropriates it to resist sexual discrimination and to overcome divisions that exist today about who counts as truly African.

In its opening statement���”This song goes out to the new slaves, the new blacks”���”Same Love” situates the experience of same-sex-loving people in Africa in a longer history of racial and ethnic oppression. The lyrics suggest continuity between the Civil Rights movements in the US and the contemporary LGBT rights movement in Africa. This is acknowledged later in the video when images of some prominent African queer individuals appear on the screen, while the vocals in the song state that “Luther���s spirit lives on.” The suggestion is that the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. lives on in those Africans campaigning for the human rights of sexual minorities today. This allows the producers of the video to claim a moral high ground, implicitly appropriating King���s prophetic dream of racial liberation in the US and applying it to the struggle for queer freedom in Africa.

Wainaina has also invoked the name of King, and of African American literary writer James Baldwin, as part of his queer pan-Africanist imagination. He referred to Baldwin as a source of inspiration, recognizing him as “black, African, ours,” as a “gay icon of freedom,” and canonizing him as a writer of “new scriptures.” While commenting on the anti-homosexuality bill in Uganda, he further stated that the pastor of former US president George W. Bush “has had more influence on the imagination of Africans than Martin Luther King and James Baldwin.” Elaborating on this, Wainaina invoked the tradition of progressive black religious thought, explicitly referring to “the Jesus of James Baldwin and Martin Luther King” which, he critically observes, is “a dead man in Africa.” Describing Jesus as a liberating figure, who is in solidarity with the marginalized, Wainaina criticized the church in Africa for maintaining structures of oppression and exclusion.

The invocation of progressive traditions of black religious thought is particularly significant in the light of popular discourses that denounce homosexuality as both ���un-African��� and ���un-Christian.��� The question whether religion, in particular Christianity, can make a constructive contribution to queer pan-Africanist discourse is a debatable one. Many African queer scholars and activists tend to see Christianity as a colonial and conservative religion from which Africa and Africans need to be liberated. This is understandable, but one could ask whether it not also reflects the influence of western queer scholarship and politics with its secular inclination and anti-religious tendencies. Both Wainaina and the “Same Love” video agree with the postcolonial critique of Christianity. Yet they also suggest that progressive traditions of Christian thought can inspire the black African queer imagination. Hence, they invite us to engage creatively and constructively with the resources within religious traditions towards black pan-African queer liberation.

January 28, 2020

Linda Ronstadt is still playing Sun City

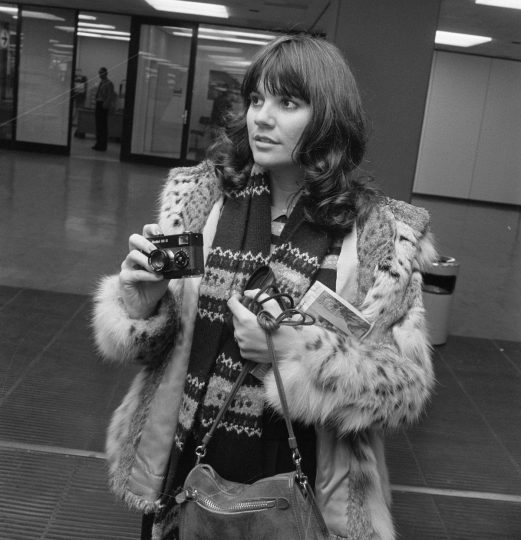

Linda Ronstadt in 1976 via Wikimedia Commons.

In a television interview from October 1983 (a clip of which made a comeback on social media), talk show host Don Lane asks a young Linda Ronstadt: ���You went to South Africa recently. Have you received criticism for going there?��� This moment arrives nearly an hour into the new documentary Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice (2019, directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman). In a short clip, we see the pop singer interviewed on the Don Lane Show, faced with a question about her performance at the infamous Sun City casino resort in apartheid South Africa.

Ronstadt���s Sun City tour landed her in the first edition of the United Nations��� ���Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa.��� The UN Register, which was sometimes referred to as a blacklist, was first published in 1983 by the UN Special Committee against Apartheid, itself established by a vote of the UN General Assembly in 1980 (which had been opposed by a handful of countries including Canada and the United States). Other performers singled out by the UN for violating the boycott over the previous two years included Liza Minelli, Olivia Newton-John, Dolly Parton, Clarence Carter, Shirley Bassey, Barry Manilow, and Rod Stewart. By 1985, the UN Register included 388 names of performers who had broken the boycott since 1981, including Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Liberace, and the Beach Boys.

Inclusion on the UN���s Register or blacklist was not final. Artists could easily be removed from the list if they signed a pledge that going forward they would boycott South Africa until apartheid had ended. And indeed, many artists readily complied: in 1985, Goldie Hawn was shocked to find herself on the Register and made clear her intentions to sign the pledge. ���I feel awful about it,��� Hawn told the Chicago Tribune, ���Warner Bros. told me it was a good market and wanted me to go there. And I was so naive, I went. I was really quite innocent until I got there and saw what a horror story it was���then I spoke my mind (against apartheid). I won`t be going back, God knows!”

���As far as I was concerned it was just a gig,��� Ronstadt told Don Lane:

I don���t think that if you disagree with the policies of the government, which I do very definitely disagree with the policies of the South African government, I don���t think that���s enough of a reason not to go and play music there. If I did that, I wouldn���t be able to play in the United States ��� if I decided that I wasn���t going to play where attitudes of racism prevailed I certainly couldn���t play in Australia or England or lots of places in the United States ���

Regrettably, the documentary quickly moves on, and can be fairly accused of glossing over the controversy. Even worse, by following the interview with a clip of Ronstadt���s friend Bonnie Raitt praising her political intellect and ���depth,��� the film effectively presents Ronstadt���s decision to perform in apartheid South Africa as a savvy and politically mature choice, and it comes across as somehow laudable.

This is unfortunate, for Ronstadt���s decision to play Sun City was not only morally wrong, but it was also an important cultural moment of the anti-apartheid era, especially in the United States. While Ronstadt certainly wasn���t alone in breaking the cultural boycott, she was nonetheless one of the most visible celebrities to do so, and unlike many other artists she refused to apologize. Her intransigence on this issue made her a key symbol in the debates over the boycott, and a flashpoint for activism. As such, the controversy deserves further reflection.

Crossing the picket line

In May 1983, Linda Ronstadt was paid $500,000 to perform 6 concerts at Sun City as a last-minute fill-in for another act that fell through. Sun City was a popular white-owned resort in the nominally ���independent��� Bantustan of Bophuthatswana, which was promoted by the South African government and its supporters in an effort to downplay the horrors of apartheid. In Sun City, Black and white South Africans could mix while partying or gambling. Using this ruse, many of the world���s best athletes (especially golfers and boxers) had been convinced to compete in events there.

Although Ronstadt was conflicted about the offer, it was reportedly Frank Sinatra who convinced her to play Sun City, who ���assured her that Bophuthatswana was fully integrated��� (Sinatra himself was paid up to two million dollars for his visit in 1981). Despite these assurances, Rolling Stone Magazine noted that the crowd that came to see Ronstadt was ���almost totally … 99.44 … percent pure-white.���

No apologies

In sharp contrast with the many artists who quickly repented after finding themselves on the UN blacklist, Ronstadt flatly refused to apologize for playing Sun City and would not sign any boycott pledge. In defending her actions, she turned the issue into a matter of principle, expressing opposition to the very idea of a cultural boycott.

“The last place for a boycott is in the arts,��� Ronstadt told Rolling Stone in 1983, ���I don’t like being told I can’t go somewhere.��� She insisted that her visit was in no way an ���endorsement��� of the apartheid government, but that “if I won’t play a repressive government, a police state ��� then I couldn’t play the black countries or Alabama or Boston.”

These are themes that Ronstadt continued to repeat for years, as illustrated in an interview with the Orange County Register in 1989. Criticizing the logic of boycotts, she remarked:

Would I play Israel? You bet. Would I play one of the Arab countries? Of course. We are directly interfering with people’s lives in Central America and, as a Latin [Ronstadt���s father was from Mexico], how can I be a member of this country, play concerts here, give aid and comfort to people who���through their tax dollars���are allowing people to be massacred and tortured? Once you start thinking like that, you have to be responsible for everything, and you can’t be that way.

In the same interview, Ronstadt questions whether cultural boycotts punished the right people, and suggests that music itself could be a force for reform: “If rock ‘n’ roll had been circulating freely through there (South Africa) from the ’60s on, I think there would have been even more of a change by now. Look what happened over here. There was a revolution in the ’60s���some of it for the good, a lot of it not so good��� but much of it for the good, and that was propelled by pop music.”

Boycotting Linda Ronstadt

Ronstadt���s unapologetic violation of the boycott made her a prominent target for the anti-apartheid movement.

Importantly, Ronstadt was an implicit target of the 1985 protest record “Sun City” (featuring the refrain ���I ain���t gonna play Sun City���) which was written by Bruce Springsteen���s former lead guitarist Steven Van Zandt who had visited South Africa twice in 1984. The song had the participation of 50 artists including Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Miles Davis and Ringo Starr, who performed under the name Artists United Against Apartheid. Initially, the charge was intended to be more explicit: original lyrics included the line “Linda Ronstadt, how could you do that? Rod Stewart, tell me that you didn’t do it,” but this was removed from the final version of the song.

Like other artists who found themselves on the UN Register, Ronstadt���s shows were picketed by anti-apartheid groups across the United States. In Los Angeles in 1988, the group Unity in Action handed out flyers that read: ���BOYCOTT Linda Ronstadt! Protest Against Collaboration with Racist Neo-Nazi South Africa!��� Many of the artists who were picketed ultimately complied with activists��� demands and agreed to sign a boycott pledge, but Ronstadt was one of only a few (with Ray Charles) who steadfastly refused.

Rubbing salt in the wound was Ronstadt���s appearance on Paul Simon���s ���Graceland��� album in 1986, which itself was controversial for being recorded in apartheid South Africa and therefore appeared to violate the cultural boycott. The collaboration did not go unnoticed; in a review of Graceland published in the Southern Africa Report (a prominent Canadian anti-apartheid newsletter), David Galbraith noted that ���It���s not hard to read [Simon���s] decision to include Linda Ronstadt, a prominent Sun City performer, on one track as a deliberate repudiation of the UN blacklist,��� adding that ���the fact that ���Under African Skies��� happens to be the worst on the album is a purely serendipitous demonstration of the symbiotic relationship between art and politics.���

For arguably breaking the cultural boycott, Simon was criticized by the African National Congress, the most prominent liberation movement at the time, and his name was added to the UN Register. However, unlike Ronstadt, Simon sought to mitigate against the criticism: in early 1987 he sent a letter to the UN supporting the principle of the boycott and promising not to perform in South Africa, and thereafter he was quickly removed from the blacklist (although some anti-apartheid groups continued to boycott his album). By 1988, the list of artists who had pledged support for the boycott, and therefore had been removed from the Register, included Frank Sinatra, Tina Turner, Eartha Kitt, Cher, and Paula Anka.

By 1991 the list of names on the UN Register was dwindling, but there was one absence that was particularly surprising: after all her objections, in the summer of 1990 Linda Ronstadt had ���quietly��� informed the UN that she wouldn���t return to South Africa until apartheid was over, and therefore her name had been deleted. Did she have a change of heart? It seems unlikely; in late 1989 she had told the Orange County Register that ���art should never, never be boycotted,��� and while she admitted that she would not return to Sun City, this was only because ���you can���t make any money doing it��� and she doesn���t ���care for casinos.��� More likely, in a time when Mandela had been released from prison and the end of apartheid seemed inevitable, she didn���t want to be among the very last names still on the list.

Why Boycott ____?

Nearly four decades later, Linda Ronstadt���s arguments against the cultural boycott ring both hollow and familiar. Her central charge — it doesn���t make sense to boycott any particular place given that racism exists everywhere — misses the point completely. After all, the logic of the cultural boycott was not that racism existed in South Africa, but rather the fact that South African liberation movements (and later the United Nations) were specifically requesting it. These organizations had provided a clear reference point for action and solidarity, which artists like Ronstadt decided to ignore while deferring solely to their own personal judgement.

This is a feature which is also lost in contemporary debates over the boycott of Israel, which tend to repeat many of the exact same arguments. The simple answer to the question of “Why Boycott Israel?” and not elsewhere is precisely because it is a response to the call from Palestinians themselves. Unfortunately, too many artists see the issue in the same individualistic terms as Radiohead���s Thom Yorke, who complained to Rolling Stone about the pressure to comply with the BDS call, saying that it is ���really upsetting that artists I respect think we are not capable of making a moral decision ourselves[.]���

In justifying their decision to boycott South Africa, a 1988 pamphlet by Unity in Action quoted African National Congress official Barbara Masekela:

No consideration of the cultural boycott that looks away from the daily occurrences in the streets of South Africa, the daily struggle and sacrifice, is of any consequence.

The cultural boycott is no rigid theoretical discourse. It is a practical political exercise that must be designed to aid and abet the initiatives of our patriots against the scourge of racist economic exploitation.

It is a question of choosing to betray or support our struggle for national liberation.

Linda Ronstadt made her choice. Let���s learn the right lessons from it.

The epidemic of thinkfluencers

Still from The People vs. The People.

Director Lebogang Rasethaba has now made at least three social justice documentary films capturing the political sentiments of young South Africans. The first film, The People vs The Rainbow Nation, tackled the disillusionment of young South Africans with the ���rainbow nation��� project in the context of the student protests of the mid-2010s. The second tackled patriarchy and gender-based violence. His most recent film, ���The People vs The People��� takes much of its style and structure from the previous two installments, but concerns itself with the interpersonal relations and behaviors of Black communities.

Rasethaba crafts his documentaries by presenting his arguments through representations of ���the People.��� Different fragments and snippets are taken from a series of filmed conversations and individual interviews that he turns into a feature length documentary. Rejecting the presence of Whiteness, as the film makes a point of declaring in its opening montage, the film centers on the interior lives of Black people in relation and objection to White supremacy. [Regarding the use of terminology: Both Rasethaba and interlocutors mean black people collectively, so as to include people deemed African, coloured and Indian in South Africa ��� Editor.]

Rasethaba is never present within these conversations or as the authorial voice linking them together. As a result, his documentaries want for authorial self-reflection. We never learn why he picked this specific group of people or their class positions, what informs his participants��� opinions and worldviews. The result is an echo chamber that reflects a much wider issue in current Black political discourse, what I���d like to term ���the epidemic of thinkfluencers.���

Thinkfluencers represent a class of people who view public activism as primarily operating in the form of public speeches, lectures, panel discussions and books or editorials as tools for liberation. It offers the individual the ability to simultaneously present a radical political persona while having fundamentally normative objectives of capital accumulation and social mobility. The population of thinkfluencers arises amongst a new middle-class of young South Africans, some who base the core of their politics under the broader umbrella of ���Fallist��� discourse. Forged amongst university students during the country-wide Fees Must Fall protests of 2015-2016, their political project drew ideas from Black-consciousness, post-modernism and post-coloniality, where identity became the base of all political action and thought. With identity as the center of one���s philosophical and political intuition, political insight is thus derived from the lived experiences of a specific identity or intersections of multiple marginalized identities. This provided ground for those who were now able to gain social standing from their ability to become spokespersons for their respective identities and as a result, gave birth to the thinkfluencer.

While Fallist ideology doesn���t have itself to blame for its proliferation in Black politic discourse, it is grounded by an afro-pessimism. It begins by being suspicious of any meaningful, structural transformations that could effect change in the conditions of black people, which protects the role of discourse since at most what we can hope for is a change at the level of the individual, one audience member at a time. It offers no meaningful challenge to the greater systems of exploitation that create economic and class inequality for the majority of South Africans.

The film series promotes the idea of politics as a series of never-ending discussions about social justice; crucially, the audience believes they���re there too and that it is imperative to have these discussions. It follows that for as long as there exists discussions about discussions that we ought to be having, we need the funding of NGO���s to sponsor these and we need the presence of thinkfluencers. More importantly, is the implicit premise that on the other side of this metaphorical seminar room, lies an unwoke and miseducated ���other��� in need of education or preaching. While the miseducated subject is never explicitly named within panel discussions, the visual medium of documentary leaves little space to keep the elephant in the room out of frame, and it���s in Rasethaba���s documentary that the hidden class antagonism of contemporary Black political discussion is revealed. We see it especially in the discussion and presentation of ���Black Love.���

���Black Love��� presents itself in the documentary as a revolutionary practice necessary for the progress of Black people. It���s a form of Black ���pull yourself up by your bootstraps��� uplift which finds its roots in respectability politics. It���s a rhetoric traditionally promoted by conservative Black public intellectuals who have no stake in changing the fundamental material conditions of the majority of Black people. So we see again concerns about absentee fathers, financial responsibility and the consumption habits of Black communities. The explanations behind them remain cultural; what was ���hip hop culture��� then, is ���toxic masculinity��� now. But chastising a group of people for their habits, without understanding the external economic and other conditions that shape their lives, is an old tactic that breeds antagonism.

The veiled class resentment in this reformed Black uplift is most evident in the discussion around the so-called ���Black Tax��� in the documentary. Black Tax is described as an auxiliary ���tax��� a Black person pays to their family members once they earn a salary or manage to financially ascend from poverty. The prevailing sentiment surrounding Black tax within Black political discourse is that it���s an ankle weight, obstructing the Black middle class from upward financial mobility. Most of the participants in ���The People vs The People��� view Black tax as a burden and manipulation of Ubuntu.