Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 188

March 2, 2020

The “China virus”

Public domain image.

When the highly infectious and deadly Ebola hit a handful of West African countries in 2014, news of how the whole African continent was battling the disease spread quickly. Ebola would claim more than 11,000 lives in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia and the cost, in economic terms, of the outbreak in those countries alone was more than $1.6 billion in losses. But the outbreak, aided by preexisting prejudices and deeply rooted stereotypes, would have incalculable impacts on the continent, its people, and far beyond. During the devastating Ebola crisis, to be ���African��� was to be a primary suspect, amplifying the never-ending stigmatization, discrimination, and blatant racism against Africa and its people.

What is going on today with regard to China is, therefore, a familiar story. The coronavirus COVID-19 is galvanizing prejudices against the Asian country and its people���resurrecting archaic stereotypes while making light of a deadly outbreak. But, there is a significant difference between these two cases. Ebola was seen as signifying Africa���s inherent helplessness, while COVID-19 combines preexisting biases with the fear of a rising China.

The US���s reaction, indeed overreaction, to the outbreak is a case in point. It illustrates the prevalent fear of a rising China that is believed to have a secret agenda to take over the world. ���Xenophobia, ideology and the Western fear for China���s rise are the triple burdens that hinder the fight against the 2019 coronavirus,��� David Monyae of Africa-China Studies at the University of Johannesburg concluded in a recent opinion piece on a South African news site. Indeed, a recent article, ���Welcome to the Belt and Road Pandemic,��� published by Foreign Policy, reinforces this argument. According to the piece, ���By making the Belt and Road Initiative endeavor���a multi-trillion dollar program to expand Chinese trade and infrastructure around the world���the epicenter of his foreign and economic policy, Xi has made it possible for a local disease to become a global menace ��� [if only] China is now impossible to quarantine.���

Such views can only help intensify the mass hysteria and anti-Chinese sentiment that has accompanied the spread of the virus. And clearly, beyond geopolitics, racism, whether acknowledged or not, is also at play. Little wonder that the World Health Organization (WHO) had to warned against ���trolls and conspiracy theories��� surrounding the viral outbreak. That didn’t stop US cruise ship company Royal Caribbean from declaring that would-be passengers and crew with Chinese passports would be banned from all of its cruise ships, irrespective of their travel history, regardless of when they were last in China. The message here is clear: to be a holder of a Chinese passport is to be inherently a carrier of the virus. That is the definition of racism.

According to the WHO it is ���very important that we provide a ��� name so no location was associated with the name ��� to ensure that there was no stigma associated with this virus.��� Yet, in reporting on the outbreak, many media outlets with global outreach have deliberately chosen to use ���China virus��� or ���Wuhan virus��� in their stories. As Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister observes, ���These are ugly times and the racism implicit (and sometimes explicit) in many responses to Chinese people around the world makes me question just how far we have really come as a human family.���

Just like during the Ebola outbreak, these stereotyping and prejudicing will continue unabated, unfortunately. But one thing is beyond doubt: viruses or, for that matter, any kind of disease, do not see color. They do not recognize the oft-celebrated borders of nation-states or ethnic enclaves. The best way, indeed, the only way to effectively defeat them is by working together, collaboratively.

March 1, 2020

Are young South Africans set up for failure?

Image credit Babak Fakhamzadeh via Flickr CC.

As the new school year kicked off in South Africa at the end of January, millions of young people were flocking the streets looking for opportunities. Those who just received their matric (or high school) results were standing in long lines to secure limited spaces at universities or colleges, recent graduates were updating and sending out their CVs to possible employers, and those who remain unemployed will try their luck again. Unfortunately, millions of young people came to find themselves closed off from career advancement opportunities.

With 36% (20 million) of the population under the age of 35, children and young people lie at the heart of South Africa���s untapped potential. Yet, more than 30% of young South Africans between the ages of 15-24 are not in any form of employment, education, or training; 46% of 25-34 year olds fall into the same category. This equates to approximately 7.9 million young people out of work, education, or training opportunities.

In the beginning of every new year, youth unemployment spikes to pandemic proportions. This is mainly due to new entrants into a labor market that is not creating enough job opportunities. During this period, among graduates between the ages of 15-24, the unemployment rate was 31% compared to 19% in the 4th quarter of 2018���an increase of 11 percentage points quarter-on-quarter.

Young people have a tough relationship with employment: youth unemployment now is recorded at 56.4%, the highest globally, and 63.4% of the total unemployed population is young people. The year 2019 recorded the highest number of retrenchments and unemployment rates in 16 years. The “old” saying remains that ���last in, first out,��� which means young people are the first in the firing line when there is high retrenchments.

The government can no longer sweep this crisis under the rug. Some legislative and policy instruments, such as the National Youth Policy (2015) and the Youth Employment Service (2019), brought about resounding hope. Yet they have not implemented many of their intended resolutions. In his first State of the Nation Address in 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa recognized youth unemployment as our ���most grave and pressing challenge��� as South Africans.

Economic and political cost of this dire situation

17 million South Africans live on social grants from the government. In 2017 alone, social grants received by people under the age of 35 increased by 11% and continue to grow at that rate. The exclusion of young people from opportunities is building a huge population of citizens highly depended on the government. The Mail and Guardian newspaper recorded that 89% of matric leaners who wrote the 2019 exams are grant beneficiaries. Most of them will be turning 18 and will be cut off and left with nothing to make way for themselves. Research by the University of Johannesburg shows that a person spends over R500 per month when looking for a job. More and more young, functional people are pushed out of opportunities and depend on the government for their livelihoods. The government was projected to spend R193.4-billion in 2018-2019 to R223.9-billion by 2020-2021, growing by an average of 7.9% annually. This is money that could be redirected to other needs of South Africans, such as health, housing, and education.

Many researchers have proven that a pool of young people who are not in employment, education, or training are more prone to be entangled in crime, drug abuse, poverty, and violence. In recent years, South Africa has been experiencing high levels of violence. This has moved to almost every part of South African society. Gender Based Violence in South Africa is now 5 times the global average, drug abuse is 3 times the global average, and murder, mental illness, violence in schools, and rates of suicide keep on increasing yearly.

The decline of youth organizations

Youth formations of the three biggest political parties have been found wanting in the past years. The African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) has been in disarray since the expulsion of its former president, Julius Malema, in 2012. The Democratic Alliance (DA), throughout its history, has not been at the forefront of issues facing the youth. Only the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which Malema went on to form, seem to have a ���legitimate��� claim on youth issues, but the party has been entangled in corruption allegations, the Venda Mutual Bank scandal, and internal leadership fights that has seen many young party members being expelled from the party.

The top levels of South African social hierarchy are still occupied by senior citizens. The average age of a Member of Parliament is said to be at 66, and the average age of a farmer is 65. This of course is seen throughout most sectors of South African society. Young people show far higher rates of unemployment than older people. This might be justified by the lack of experience among young people, yet the gap shouldn���t be this huge due to the diminishing number of senior citizens and the rise of young people. This is not to say old people must be replaced with young people, but it shows that more spaces, specifically for young people, must be created.

The country cannot continue losing young people to poverty and unemployment. Millions of young people with talent are wasted year in year out. A country that doesn���t invest in its youth will fail at solving its immediate and future challenges. It is evident for now that young people do not know where to go; in 2019 the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) recorded a 47% decrease in youth voter turnout. As young people, it is time to demonstrate and put this crisis at the center of national dialogue. This will require united campaigns and action from all young people across the country.

February 27, 2020

We wear the masks

Still from HBO's Watchmen.

In Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons���s cult and admittedly pasty white graphic novel Watchmen, superheroes first appeared in the late 1930s, but they have profoundly changed the course of history, most notably in the Cold War. Dr. Manhattan, a god-like, blue-skinned demiurge born in a lab accident, won the Vietnam War for the United States, the Asian country becoming the 51st state of the Union. Set in 1985, the graphic novel followed members of America���s most prominent (and now disbanded) superhero group as they discovered the massive conspiracy organized by Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias, the most intelligent man on Earth���to ward off the threat of nuclear war between the USSR and the USA, Ozymandias makes up an alien attack that wipes out half of New York���s population and convinces the blue man to go into exile on the red planet, Mars. And that is as much color as we���ll get.

The HBO television series Watchmen picks up in the year 2019 of this parallel world. What harmony the alien enemy may have first brought appears not to have lasted long, though in many ways these United States have profoundly changed. Under President Robert Redford, the country at large has made efforts to curb systemic racism, for example with the passing of the Victims of Racial Violence Act granting reparations (or Redfordations, in the parlance of the day) to victims of racist terror, most notably descendants of people killed in the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma Massacre (an actual historical event). It appears the government has also attempted to tackle police violence, their training and new rules of engagement have forced strict oversight notably in their use of weapons. These changes have not come easy. The white supremacist secret organization the Seventh Kavalry (whose members sport masks spray-painted with Rorschach motifs in homage to Watchmen���s eponymous fascistic and deranged vigilante) has violently opposed them all. For example, on December 25, 2016 they organized a widespread attack on police officers throughout Tulsa. In the aftermath of the “White Night,” legislation was passed by which police officers go masked at all times, some adopting superhero-like costumes and identities. Prominent among them is Angela Abar, aka Sister Night, played brilliantly by actor Regina Knight. As the series begins, the Seventh Kavalry has become active again.

During Watchmen���s run in late 2019, comments made in a 2016 interview by the original graphic novel���s writer Alan Moore to a Brazilian magazine started making the rounds online:

Save for a smattering of non-white characters (and non-white creators) these books and these iconic characters are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race. In fact, I think that a good argument can be made for D.W. Griffith���s Birth of a Nation as the first American superhero movie, and the point of origin for all those capes and masks.

This argument, eloquently made a few years earlier by Chris Gavaler, hovers over the entire season and most significantly in episode six, ���This Extraordinary Being,��� in which Angela Abar, having taken the memory drug Nostalgia, gets to experience episodes in the life of her grandfather, Will Reeves. In the process, Angela discovers secrets of her family���s past. Much like her grandfather and myriad superheroes, Angela became a masked vigilante in the aftermath of tragedies, which, for being personal, are imbricated in much broader systems of violence and oppression (Jim Crow-era systemic racism for Will and the aftermath of the annexation of Vietnam for Angela) that each of them first only recognized partially. Much like him, she lived under the false assumption that she could right systematic wrong through feats of individual bravery.

As she explores her grandfather���s life, Angela uncovers a secret history of the US. It involves a nationwide racist conspiracy: the Seventh Kavalry turns out to be but the latest incarnation of Cyclops���once the psy ops branch of the Ku Klux Klan with deep roots in the police���whose 1940s plan to use subliminal messages in order to exterminate the US���s people of color was only thwarted thanks to the intervention of Hooded Justice, America���s first superhero and Angela���s estranged grandfather. They are back with a vengeance and so is he: or, as the series suggests most pointedly, neither ever left.

In Watchmen, a show self-consciously obsessed with popular culture, history does not repeat itself: it rewinds, reruns, and is remade, new characters appearing under new titles and masks to reenact the same old story. Even as they are revealed, each layer provides but a partial picture, and what we are ultimately left with is the disturbing notion that there is no nation beneath the masks. The US has been and will continue to be���as long as it fails to properly address this history and its consequences���the racial masquerade itself.

Watchmen is at its best when it addresses the role played by popular culture in stamping race in the American collective imaginary. The first episode���s opening scene proves a template, the first instance in the recurring frame narration that characterizes the whole series��� structure. It purports to be an excerpt from a silent film, all jumpy black and white footage and jaunty piano music: a white man dressed in white clothes and a white hat rides his white horse, turning to shoot at the ominous black-cloaked figure chasing him on a black horse, twirling a lasso. Soon the rope cinches around the white rider and he is thrown off his horse in front of a skinny white church. The all-white congregation exit in a panic: the man in white is their sheriff, but as the man in black reveals, he is also the cattle rustler who has been stealing from them. The man in black drops his mask, revealing himself to be ���BASS REEVES! The Black Marshall of Oklahoma!��� The congregants call for the thief to be lynched, but Bass Reeves will have none of it: ���There will be no mob justice today. TRUST IN THE LAW.��� The title card is spoken out loud with infectious glee by the lone little boy watching the film in what turns out to be a Tulsa, Oklahoma movie theater in 1921. Moments later, the boy and his parents have to run for their lives as a rabid white mob rampages through Black Wall Street, shooting African Americans on sight.

On top of exposing an atrocious and still widely forgotten episode in actual US history, the scene packs several origin stories: the little boy, Will Williams, will see his parents die, survive the massacre and rename himself Will Reeves after his childhood hero. Like Marshall Bass Reeves, he becomes a lawman. When faced with corruption and terror within police ranks, in the guise of Cyclops, he also decides to take the law into his own hands. He becomes Hooded Justice, once again inspired by the Western hero of his youth���himself a movie take on a real life, relatively unsung, black hero of the West. The scene proves a way station in the US���s history of race, and provides a glimpse into its codes and conventions of representation.

In ���Change the Joke and Slip the Yoke,��� Ralph Ellison discusses blackface as an inherently American form; ���its function was to veil the humanity of Negroes thus reduced to a sign, and to repress the white audience���s awareness of its moral identification with its own acts and with the human ambiguities pushed behind the mask���(103). Positing blackface as one of the typically American instances of mask-wearing, albeit an ideologically charged one, Ellison went on to say that ���[Americans] wear the mask for purposes of aggression as well as for defense, when we are projecting the future and preserving the past. In short the motives hidden behind the mask are as numerous as the ambiguities the mask conceals��� (109).

This is as broad a statement as it is insightful, simultaneously recognizing the weight of racial thinking and the possibility of individual complexity within and beyond it. The statement also resounds with the echoes of an older, more pointed statement by Frederick Douglass, who on seeing the minstrel show fad take Great Britain by storm in the mid-19th century, declared blackface to be ���a mode of warfare ��� purely American.��� By the time we find Will Reeves at the movie theater, this mode of warfare had become a crucial thread in the cultural fabric of America, pervading its popular arts.

In 1896, African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar became nationally renowned for his verse, some of it notably written in so-called Negro dialect, or African American Vernacular English. He soon found that the freedom to use the vernacular could also be a prison: the expectation of white audiences raised on minstrelsy and related sense of black authenticity meant that little distinction existed in the public sphere between that legacy of racist entertainment and the new forms black artists managed to put out in the world. The ���Poet Laureate of the Negro Race��� was also ���Prince of the Coon Songs,��� and the authenticity of his speech was painted over by the stage conventions of minstrel shows: mask upon mask, as Dunbar famously lamented:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes���

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Those subtleties, Dunbar found out, were lost on most of his audience. No way around masking in Jim Crow USA. The rising myth of Dunbar���s day was that of a hero of blinding whiteness, the cowboy as a modern-day knight bandied by the likes of Rough Rider Theodore Roosevelt and his college buddy Owen Wister, author of bestselling novel The Virginian (1902). In the novel, a western judge justifies the western practice of lynching cattle rustlers, which according to him proves ���that Wyoming is determined to become civilized,��� by contrast to southern lynching which in its use of torture and reliance on spectacle, proves the South to be ���semi- barbarous.��� ���When your ordinary citizen ��� sees that he has placed justice in a dead hand, he must take justice back into his own hands,��� the judge continues, defining vigilantism as the ���fundamental assertion of self-governing men.���

Not by chance is this the very situation in which we find Bass Reeves in the film that does so much to impress Will Reeves. Wister���s Virginian did not think twice about stringing up rustlers, even friends of his. (White) civilization demanded it. That Bass Reeves would refrain from it on film is shown as evidence of his humanity, and as such is echoed in the seemingly na��ve trust Will���s father, Will himself, his son, and Angela, last of the line, all put in the US military and police, putting their lives on the line to defend institutions that all harm them in varied ways. ���Trust in the law,��� Bass Reeves��� tagline, seems paradoxical in a context when nothing is quite what it seems, lawmen are criminals and justice seekers are forced to go masked. Reeves speaks of the law, but he means justice; he pronounces his tagline but simultaneously, unwittingly, ���mouths a myriad other subtleties��� young Will won���t be able to hear for a long time.

In my recent book The Black Avenger in Atlantic Culture, I argue that questions around the legitimacy of violence in the face of systemic injustice in the Americas all derive from the issue of black politics, and have entered US popular culture by way of it. By the time of the US Civil War, that slavery demanded retribution was clear to all, including supporters of that peculiar institution. It bears noting that the rhetoric of justice was perversely appropriated in the Reconstruction by Secessionists defeated in the field of battle in order to justify their promotion of racist terror as appropriate response to alleged “Negro Rule.” Thomas Dixon���s wildly popular Klan Cycle trilogy and their later adaptation by D.W. Griffith into the blockbuster Birth of a Nation (1915) purported to extend Wister���s western lone man heroism to southern mass terrorism, and for all accounts and purposes, in mainstream US culture it worked. What African American responses were produced in response to this trend tended to simply offer white knights painted black.

Thus among Bass and Bill Reeves��� ancestors is Abe Overley, the hero of R. L. Waring���s 1910 novel As We See It. The novel takes place in 1876, centennial of the US, a year before the official end of Reconstruction and, as it happens, the time when the real Bass Reeves first became Deputy Marshall. Waring���s message for Jim Crow USA is fairly black and white, and intensely Wisterian: there are noble and despicable people in both black and white races, each community���s natural aristocrats should get their due. Enter his main characters, the two Abe Overleys, one black, one white, friends since birth and a living advertisement for the idea that if natural heroes held hands they���d make this world a better place. They are both attending the progressive Oberlin University when black Abe���s mother and sister are beaten to death by a gang of white racists. He turns into “the very incarnation of the avenging demon,” and takes them down one by one, western-style. Speaking of him in light of this decision, one of his white college professors says admiratively: ���This Negro is a white man.���

This is how Waring���s hero, though he kills four white men in the South, manages to live���because in the fictional economy of the novel, his action is a form of masking. In becoming an avenger, he���s effectively putting on a white mask that grants him status as an individual. What he loses in the process, though, is an understanding of injustice as a systemic issue. The racism that killed his parents is no longer political, it is personal, a matter opposing just him and the group of men who killed his mother and sister. This choice turns him from racial menace to honorable man by symbolically turning him white.

Reeves��� wife June reads right through it all. In the conversation the two have together after Reeves first becomes Hooded Justice, she makes William retell Bass Reeves��� story: ���What color are the townsfolk?��� she asks, subtly pointing to the obvious. He can only achieve justice outside of the system, but even then he will have to make all believe that he is white. Black action in Jim Crow USA is necessarily political, and he can only get away with his assault on Cyclops by painting a white mask under his hood, another layer in the masquerade.

There seems to be no taking off the masks���under each layer, Reeves finds another, more disappointing one. Captain Metropolis, the other masked hero who invites him to join the superhero group the Minutemen, has no interest in fighting racism and does not hesitate to peddle racist imagery to sell advertising for bank protection. Both heroes are in the closet, and tellingly Gardner prefers it that way. He suggests they should both wear their costumes during sex. Secret identities have a way of folding upon themselves. Hooded Justice sets out on his own against Cyclops, and it seems that in destroying the warehouse containing their documents and material for national takeover, he erases their threat. We know better of course. Cyclops is but the latest symptom of an ancient disease. There is nothing a single hero can do.

Reeves learns the oldest lesson in the book���because it can only deal with the surface of things, the mask as it were, individual revenge can never satisfy. It ruined Reeves���s life and passed on the trauma of the Tulsa Massacre like a genetic disease. Hooded Justice disappears underground and only returns to pass the torch on to his granddaughter, Sister Night, along with a bit of wisdom. Speaking of demiurge Dr. Manhattan, he deadpans: ���He was a good man. But considering what he could do, he could have done more.���

The series stops before we can find out if Angela, now potentially the new goddess in town, heeds this call. But then, maybe it is not just meant for her ears, but that, on the lower frequencies, he speaks to us.

February 26, 2020

Zimbabwe���s forgotten football history

Football in Zimbabwe now looks way different from the 1960s. Image via Coca Cola South Africa on Flickr CC.

Before majority rule in 1980, Rhodesia (colonial Zimbabwe) was briefly a member of FIFA, and even played a World Cup qualifying match in 1969. A year later, the team was suspended from global football. In the 1970s, football continued domestically under John Madzima, one of the vice-presidents of Rhodesia���s national football association, who successfully launched a coup against the white leadership. After independence, Madzima became the first head of the Zimbabwe Football Association (ZIFA). ZIFA has had organizational and financial difficulties and few continent-wide successes. Nonetheless, football has a profound social and political legacy from the colonial period, perhaps the only area of social life under black control.

Football passed from industrializing Britain to the colony then known as Southern Rhodesia in 1890 by soldiers, and later missionaries and white settlers. Sport was central to white identity. Even mining baron Cecil Rhodes, the colony���s namesake, was an avid sportsman. For whites, football served an important purpose: a way of building a (white) Rhodesian identity. White settlers had high rates of emigration and often lived in rural areas.

But, as elsewhere, sport was also a tool of social control. Mine workers from Transvaal brought football to Rhodesia���s black community about 1923. Township clubs sprang up almost overnight due to the logical rules and low costs of the game. African Welfare Societies, government-supported agencies that provided social services to the townships, created football infrastructure that could divert black workers from more “dangerous” activities such as gambling or protests.

In Southern Rhodesia, football was organized around private clubs. The most important black elite football clubs were Highlanders FC in Bulawayo (founded in 1926) and Dynamos FC in Harare (founded in 1963). The Highlanders tended to have Ndebele fans while Dynamos had Shona fans. Football games saw political protest, especially when playing white teams. The most successful protest occurred in Bulawayo in 1947, when fans sat home for two seasons to protest the city council���s attempted takeover of the football fields.

Because football was organized around private clubs, racial discrimination was common. White clubs were often ethnic based with separate clubs for Scottish, Portuguese, and Greek settlers, for instance. The difference between black and white clubs was stark. Black clubs had to lease or share sports facilities. While some clubs became integrated and participated in multiracial competition, most did not. Apartheid South Africa affected Rhodesian sport as well. Only segregated teams could play in or tour South Africa. Nonetheless, football dwarfed all other sports. A rugby cup final could attract 6,000 spectators. By the 1960s, a football cup final had 30,000 spectators.

The Southern Rhodesia Football Association (SRFA) applied for FIFA membership in 1961, three years after admitting black players and the national team was racially integrated. In 1963, Dynamos FC won the Austin Cup, a major cup tournament that was until then whites-only. However, most SRFA-affiliated clubs remained white, while black clubs were affiliated to a separate organization, the Southern Rhodesian African Football Association. Mixed-race and South Asian clubs were affiliated to the Southern Rhodesian Soccer Board. These competing organizations merged into the Football Association of Rhodesia (FAR) and officially joined FIFA on May 21st, 1965. But, racial discrimination did not disappear. Voting in FAR was still weighted toward the predominantly white clubs in SRFA and private clubs set their own membership rules.

Just six months after FIFA membership, Rhodesia���s white settlers unilaterally seceded from Great Britain and established an increasingly draconian police state. Mandatory United Nations sanctions excluded athletes from sport competition abroad. For FIFA, nothing changed. Stanley Rous, infamous for his support of apartheid South Africa���s membership, was still FIFA President. The African continent was underrepresented on the FIFA Executive Committee.

Rhodesia was therefore eligible to compete in the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. Because other African teams would boycott, Rhodesia had to be moved to the East Asia/Oceania group. Ultimately, the compromise was that South Korea, Japan, and Australia played in Seoul, with the winner (Australia) to play Rhodesia in Maputo. Rhodesia held Australia to 1-1 and 0-0 ties, but lost the third game 3-1.

After the 1970 World Cup, Rhodesia was suspended from FIFA. FIFA recognized teams from colonies and from independent countries, but Rhodesia under UN sanctions did not fit either category. When, two years later, the FIFA Executive Committee recommended lifting the suspension, the African membership revolted. The continent now had enough seats on the Committee to block the proposal.

Rhodesian football turned inward. Racial segregation continued to exist in football even though the overwhelming majority of clubs, players, and fans were nonwhite. John Madzima led a revolt by the African clubs. In October 1973, he formed the competing National Football Association of Rhodesia (NFAR), which absorbed the clubs and players as well as the major cups and sponsorships. The old FAR became defunct. In February 1974, Madzima applied for FIFA membership. FIFA refused to recognize NFAR: Rhodesia���s suspension was over the country���s unclear political status, not racial discrimination.

In April 1980, Zimbabwe achieved majority rule. FIFA lifted the suspension and Madzima became ZIFA head. Zimbabwe has been somewhat mediocre in African and World Cup football since then. It is among a handful of African countries that has never made it past the top-16 in the African Cup of Nations, though it had a comeback in recent years at the Southern African regional level. Football���s uneven development in the country is a legacy of decades of racial segregation. However, the resilience of football���s black leadership during the period of white rule preserved the country���s most popular sport during its darkest period.

Thanks to the FIFA librarian Michael Schmalholz and the FIFA archivists in Zurich for their invaluable assistance.

February 25, 2020

Impounded sandwiches

Image via Media Club South Africa on Flickr CC.

In early February, the Johannesburg Metro Police Department impounded sandwiches for sale by Itumeleng Lekomamyane, a trader in the downtown central business district. Both tragically and comically, the return of the now-stale sandwiches was made contingent on the payment of a R1,600 fine, or a little over $100. (The national minimum wage in South Africa is currently $1.34 per hour or $234 per month.)

The prominent Indian urbanist Gautam Bhan once remarked in a lecture that the trouble with South Africa is that the state was strong enough to police the poor, but not strong enough to deliver the growth and development that would actually make them less poor. The country���s urban poor are expelled en masse from the cities and relegated to the periphery, where they languish far from economic opportunity.

In contrast, he said, the Indian state is simply weak: too weak to help the poor, but also too weak to victimize them to the same degree. So, the urban poor occupy the best land in the city, close to the center and major economic nodes. As a result, while in both countries the poor mostly remain poor, in India they can at least walk to work. South Africa has, in a way, the worst of both worlds.

Bhan���s analysis describes perfectly what happened to Mr. Lekomamyane: he is one of the approximately 13 million South Africans of working age for whom the state has been unable to create or facilitate employment in the formal sector. As a result, he made his own work, by all accounts with great success. But the state, unable to resist exercising the power it does have, nonetheless criminalizes his business.

Modern policing has its origins in the repression of the working class. In the UK, the first police forces were established to manage a newly urbanized proletariat. In the American South, they grew out of the slave patrols organized by planters to track down their escaped property. And in South Africa they grew out of the colonial policing system, originally pioneered by the Royal Irish Constabulary to suppress anti-colonial sentiment by the natives of that island.

The Natal Mounted Police, the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police in the Eastern Cape, and the Cape Constabulary were all established in the 19th century to suppress the nonwhite populations in rural areas and ���manage��� their presence in cities. A hundred years later, the major function of the South African Police was to enforce the complicated system of labor control and wage suppression that constituted apartheid. And the Security Branch and associated secret police forces were explicitly tasked with preventing the emergence of organized resistance to the regime. The recently reopened inquest into the 1982 detention and resultant death of trade unionist Neil Aggett is currently a daily reminder of the tactics of the police to these ends.

As criminologist Jonny Steinberg has pointed out, the practices of the apartheid police quickly re-emerged in post-apartheid South Africa: ���the old paramilitary model of exerting unilateral control over urban space quickly re-emerged: night-time invasions of township neighborhoods by squads of heavily armed men backed by airborne support; the indiscriminate arrest of young men by the truckload; widespread police violence both against detainees and on the streets.��� Even the veneer of democratic reform was soon replaced by an explicitly remilitarized police force.

That���s not to say that the police today are an unreformed apartheid or colonial-era police force. Steinberg argues that they are serving multiple functions, and have multiple relationships with the civilian population. What seems beyond question, however, is that among others, one major historical function of the police remains: to manage the poor.

We see this in the placement of police stations to control entrance to and exit from settlements like Diepsloot, exactly where the apartheid police placed their stations. We see it in the deployment of armed police against protesters, just as colonial forces repressed opposition to occupying regimes. And we see it when street traders, making do for themselves when the state can do little for them, have their goods impounded by the metro police and their business otherwise prevented.

Lekomamyane is a sympathetic and charismatic figure, which is one reason why his story has received coverage and attention. But every day, in ways large and small, the police are doing what they have always done.

February 24, 2020

The legend of flying Africans

Still from Uncut Gems.

In A24���s latest crime thriller, Uncut Gems, everything begins in Ethiopia. Opening with injury, the film starts in 2010 at the scene of two familiar crimes���the exploitation of land and of man. First, an African miner emerges from the Welo mines of Ethiopia carried by his coworkers. His leg, mangled and bleeding, demands the attention of medics and mine managers alike. Shots of the man���s bone exiting his skin are soon replaced by those that show another protrusion. Though his bloodshed breeds commotion and conflict, the mine, always a worksite, continues to produce profit in the wake of his cries. Unearthed in the mines by another set of miners, the film���s namesake appears���an uncut black opal. The stone, still married to rock, shimmers even in the darkness, as if it were promised to a life beyond the mine. Propelling the rest of the story, the jewel swiftly leaves the African continent and all of 2010 behind. And though its geography changes, matters of extraction and indebtedness seem to follow the opal throughout it travels���haunting every transaction made in its name.

Reappearing in 2012 in the office of New York-based jeweler Howie (Adam Sandler), the opal has been smuggled into the city in a fish carcass, and it is subsequently advertised through folklore. Though the majority of the mining that takes place in Ethiopia is, in reality, dedicated to gold, tantalum, phosphorus, iron, salt, and gas reserves, the film zeroes in on the country���s gemstones. Howie asserts that the black opal exists in surplus amongst ���black Jews��� who���ve been ���trapped in Ethiopia.��� As he explains, these people who���ve allegedly grown numb to the stone���s beauty are both the ���chosen people��� and the ���first peoples��� of mankind, both Jewish and Ethiopian. ���This is old-school, Middle-Earth shit,��� Howie remarks. Cleaning the stone���s origin story of its impurities, Howie goes on to divorce the opal from its past as a product of violent systems of extraction. Still, though the explicit image of exploited black laborers and non-black overseers is erased from the opal���s American debut, the film���s black characters seemingly have the most intimate interactions with the gem. And it is through their encounters with the opal���in Ethiopia and the United States���that the violence and power of Howie���s narrative work is realized.

While introducing the gem to Boston Celtics player Kevin Garnett, Howie the jeweler transforms into Howie the orator. As if to suggest the stone���s unique significance to his black costumer, Howie gives an impassioned speech about the gemstone. Like any good salesman, Howie tailors his pitch his buyer. Waxing poetic about the black opal, he introduces the stone to the NBA star as an unproblematic beauty with distinctly black African origins. Enraptured by the stone and its story, Garnett and his posse opt to take the gem immediately���in the hopes that the opal���s assertiveness might rub off on the court. And though Garnett gives Howie his championship ring to hold as collateral, somehow the transaction still feels wholly uneven. Uninformed of the true past of the opal, Garnett puts a piece of his personal legacy on the line in order to access an exploited diasporic one. As the movie goes on, the baller���s manic obsession with opal proves to be a vulnerability he cannot shake.

Embodying a dramatized sensitivity to African folklore, the black characters in the US demonstrate both spiritual and political attachments to opal. Even Howie���s assistant Demany (Lakeith Stanfield), who recruits high-profile clients for a living, is not immune to the powerful narrative Howie spins. ���Black Jew power!��� Demany shouts as he exists the jewelry shop, emboldened by the almost-sale. Entranced by the stone, an eager Garnett vows to purchase the opal, once and for all, when Howie puts it up for auction. As Garnett explains, his relationship to the opal is distinct. The gem speaks to him, makes him feel as if he can fly. It is almost ancestral, the bond he describes. In thinking of diasporic flight, one might even recall the legend of flying Africans���the folklore of enslaved peoples who dreamt of mobility through ancestral air-lifted escape. Yet, in the case of Garnett, the Black American athlete who seeks to own his little piece of Africa, ancestral flight ends by crash-landing.

Toward the end of the film, when Garnett discovers the truth of the opal���s violent past, he must contend with two kinds of betrayal at once. As he breaks down, accusing Howie of ���playing with [his] emotions��� and ripping off the workers at Welo, he must also grapple with his role in the scheme. As a buyer, he must consider his own complicity, that which implicates him and all those involved in the violence perpetrated by the Western jewelry industry. But still there is more. On a personal level, he must face his own vulnerability, that which made him a prime target for the specific kind of manipulation Howie employs���a na��ve diasporic yearning for connection to the continent. Complex yet coherent, this development reveals a theory of blackness built into the world of Uncut Gems.

Whether the film is exploring labor relations in Ethiopia or race relations in New York City, what unifies its black characters is that they all occupy the position of exploitable subjects. Across geographies and cultures, they each come to occupy a relational identity, best conveyed by the making of capital out of casualty. In this way, the film���s hijinks embody the chaotic and unsettling truths that undergird our world. Uncut Gems reminds us that there is no such thing as unproblematic beauty, that both wealth and wins come at a cost���that under capitalism, objects, people, and histories can and will be appraised.

February 23, 2020

Family politics and the supernatural

The Letter promotional poster.

African documentary films rarely provide a window into intimate family disputes. The Letter by Maia Lekow and Christopher King, takes viewers to the rural and urban communities of coastal Kenya, and explores generational debates about land, tradition and the politics of inheritance. Lekow and King deserve praise for their balanced and empathetic look at a contested tradition. The Letter is both a story of complex familial dispute, and a tale of everyday class, religious and education contestations in contemporary Kenya.

In the opening scenes we meet Karisa, a young artist/performer hustling his way to a modest living in Mombasa. Through social media, Karisa learns of troubles back home, he travels to the rural hinterland of Kilifi county, 50 kilometers from Kenya���s largest coastal city, to investigate witchcraft accusations against his grandmother, Mama Kamango.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Kamango, born in 1925, is an ageing matriarch in charge of the family farm. Her family typifies the middle class struggles of rural communities on the periphery of expanding economic development, too often centered on mega cities like Nairobi. A collection of retired civil servants, farmers and professionals, they possess a wide range of educational and religious backgrounds, which color individual explanations of everyday struggle and family misfortune. Witchcraft operates at both the center and the margins in this story. Placed amidst widespread witchcraft accusations, violence and even murder of elders in Kilifi County, we learn Mama Kamango has also been accused and threatened. The accusations against her come from within her family, as rumors spread that her actions are at the heart of a variety of family misfortunes.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.As scholar James Smith has shown, witchcraft and development debates in rural Kenya collide at the local and family level. With few opportunities for advancement in small agricultural towns like those in The Letter, families often depend on urban remittances or measly government pensions to scrape by. Central to most family investment is the control and inheritance of small parcels of land. So, when the documentary takes its audience to a makeshift shelter for elders cast away and threatened by witchcraft accusations, we learn that land and rural impoverishment is central to the debate. As one elderly man in the shelter notes ���they got rid of me to sell my land ��� I worked that land my whole life and now I am stuck here.”

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Unlike popular media and cinematic portrayals, which dismiss beliefs about witchcraft as ���primitive��� tradition, The Letter takes a multifaceted and empathetically modern approach. We hear from both sides of the family debate, as Christian belief systems clash with supernatural and scientific explanations of illness, infertility and death. However, the more Karisa investigates the accusations against his grandmother, we learn that the debate over the supernatural is secondary to the politics of inheritance and deeper family disputes.

On the shoot for The Letter.

On the shoot for The Letter.In the end, Karisa���s aunties are pitted against his uncles in a battle over their maternal upbringing, polygamous traditions and land. The climax of the film also shows competing Christian traditions as both sides bring their religious backers into the debate over just how to cleanse/reconcile a complex family dispute. Told from the voices at the center of the debate, the film doesn���t dismiss either side, even as it leans towards Karisa���s generational skepticism and his grandmother���s plight. Without a clear narrator, the film also does not seek to answer the broader question about witchcraft in contemporary Kenya. Rather it exposes how witchcraft is more importantly a spiritual/supernatural manifestation of everyday misfortune.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.For an East African audience, The Letter will likely resonate with the generational and spiritual debates, which often clash within families spread across rural/urban and class divides. For teachers, this documentary will spark rich class discussion and provide an empathetic look at contested traditions many students simply dismiss.

As a scholar of Kenyan history, I would have liked to see the film contextualize the gendered and generational debates more. For instance, even as Karisa challenges traditional elder patriarchal authority he also tells us that ���In the family there are those fundamental people you respect like your uncles. Whatever he���s been telling you he is the backbone of the family. So, when he tells you someone is a witch ��� you will believe because he���s the elder.��� This gendered generational and class debate is implied but not fully addressed in the film as Karisa���s educated and urban aunties challenge more traditional, rural forms of patriarchy. However, these points are minor distractions from the excellent work Lekow and King have put into their film. The Letter is certainly worthy of distribution beyond the film festival circuit. I hope to see it in a popular streaming service soon.

Family Politics and the Supernatural

The Letter promotional poster.

African documentary films rarely provide a window into intimate family disputes. The Letter by Maia Lekow and Christopher King, takes viewers to the rural and urban communities of coastal Kenya, and explores generational debates about land, tradition and the politics of inheritance. Lekow and King deserve praise for their balanced and empathetic look at a contested tradition. The Letter is both a story of complex familial dispute, and a tale of everyday class, religious and education contestations in contemporary Kenya.

In the opening scenes we meet Karisa, a young artist/performer hustling his way to a modest living in Mombasa. Through social media, Karisa learns of troubles back home, he travels to the rural hinterland of Kilifi county, 50 kilometers from Kenya���s largest coastal city, to investigate witchcraft accusations against his grandmother, Mama Kamango.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Kamango, born in 1925, is an ageing matriarch in charge of the family farm. Her family typifies the middle class struggles of rural communities on the periphery of expanding economic development, too often centered on mega cities like Nairobi. A collection of retired civil servants, farmers and professionals, they possess a wide range of educational and religious backgrounds, which color individual explanations of everyday struggle and family misfortune. Witchcraft operates at both the center and the margins in this story. Placed amidst widespread witchcraft accusations, violence and even murder of elders in Kilifi County, we learn Mama Kamango has also been accused and threatened. The accusations against her come from within her family, as rumors spread that her actions are at the heart of a variety of family misfortunes.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.As scholar James Smith has shown, witchcraft and development debates in rural Kenya collide at the local and family level. With few opportunities for advancement in small agricultural towns like those in The Letter, families often depend on urban remittances or measly government pensions to scrape by. Central to most family investment is the control and inheritance of small parcels of land. So, when the documentary takes its audience to a makeshift shelter for elders cast away and threatened by witchcraft accusations, we learn that land and rural impoverishment is central to the debate. As one elderly man in the shelter notes ���they got rid of me to sell my land ��� I worked that land my whole life and now I am stuck here.”

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Unlike popular media and cinematic portrayals, which dismiss beliefs about witchcraft as ���primitive��� tradition, The Letter takes a multifaceted and empathetically modern approach. We hear from both sides of the family debate, as Christian belief systems clash with supernatural and scientific explanations of illness, infertility and death. However, the more Karisa investigates the accusations against his grandmother, we learn that the debate over the supernatural is secondary to the politics of inheritance and deeper family disputes.

On the shoot for The Letter.

On the shoot for The Letter.In the end, Karisa���s aunties are pitted against his uncles in a battle over their maternal upbringing, polygamous traditions and land. The climax of the film also shows competing Christian traditions as both sides bring their religious backers into the debate over just how to cleanse/reconcile a complex family dispute. Told from the voices at the center of the debate, the film doesn���t dismiss either side, even as it leans towards Karisa���s generational skepticism and his grandmother���s plight. Without a clear narrator, the film also does not seek to answer the broader question about witchcraft in contemporary Kenya. Rather it exposes how witchcraft is more importantly a spiritual/supernatural manifestation of everyday misfortune.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.For an East African audience, The Letter will likely resonate with the generational and spiritual debates, which often clash within families spread across rural/urban and class divides. For teachers, this documentary will spark rich class discussion and provide an empathetic look at contested traditions many students simply dismiss.

As a scholar of Kenyan history, I would have liked to see the film contextualize the gendered and generational debates more. For instance, even as Karisa challenges traditional elder patriarchal authority he also tells us that ���In the family there are those fundamental people you respect like your uncles. Whatever he���s been telling you he is the backbone of the family. So, when he tells you someone is a witch ��� you will believe because he���s the elder.��� This gendered generational and class debate is implied but not fully addressed in the film as Karisa���s educated and urban aunties challenge more traditional, rural forms of patriarchy. However, these points are minor distractions from the excellent work Lekow and King have put into their film. The Letter is certainly worthy of distribution beyond the film festival circuit. I hope to see it in a popular streaming service soon.

Supernatural politics

The Letter promotional poster.

African documentary films rarely provide a window into intimate family disputes. The Letter by Maia Lekow and Christopher King, takes viewers to the rural and urban communities of coastal Kenya, and explores generational debates about land, tradition and the politics of inheritance. Lekow and King deserve praise for their balanced and empathetic look at a contested tradition. The Letter is both a story of complex familial dispute, and a tale of everyday class, religious and education contestations in contemporary Kenya.

In the opening scenes we meet Karisa, a young artist/performer hustling his way to a modest living in Mombasa. Through social media, Karisa learns of troubles back home, he travels to the rural hinterland of Kilifi county, 50 kilometers from Kenya���s largest coastal city, to investigate witchcraft accusations against his grandmother, Mama Kamango.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Kamango, born in 1925, is an ageing matriarch in charge of the family farm. Her family typifies the middle class struggles of rural communities on the periphery of expanding economic development, too often centered on mega cities like Nairobi. A collection of retired civil servants, farmers and professionals, they possess a wide range of educational and religious backgrounds, which color individual explanations of everyday struggle and family misfortune. Witchcraft operates at both the center and the margins in this story. Placed amidst widespread witchcraft accusations, violence and even murder of elders in Kilifi County, we learn Mama Kamango has also been accused and threatened. The accusations against her come from within her family, as rumors spread that her actions are at the heart of a variety of family misfortunes.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.As scholar James Smith has shown, witchcraft and development debates in rural Kenya collide at the local and family level. With few opportunities for advancement in small agricultural towns like those in The Letter, families often depend on urban remittances or measly government pensions to scrape by. Central to most family investment is the control and inheritance of small parcels of land. So, when the documentary takes its audience to a makeshift shelter for elders cast away and threatened by witchcraft accusations, we learn that land and rural impoverishment is central to the debate. As one elderly man in the shelter notes ���they got rid of me to sell my land ��� I worked that land my whole life and now I am stuck here.”

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.Unlike popular media and cinematic portrayals, which dismiss beliefs about witchcraft as ���primitive��� tradition, The Letter takes a multifaceted and empathetically modern approach. We hear from both sides of the family debate, as Christian belief systems clash with supernatural and scientific explanations of illness, infertility and death. However, the more Karisa investigates the accusations against his grandmother, we learn that the debate over the supernatural is secondary to the politics of inheritance and deeper family disputes.

On the shoot for The Letter.

On the shoot for The Letter.In the end, Karisa���s aunties are pitted against his uncles in a battle over their maternal upbringing, polygamous traditions and land. The climax of the film also shows competing Christian traditions as both sides bring their religious backers into the debate over just how to cleanse/reconcile a complex family dispute. Told from the voices at the center of the debate, the film doesn���t dismiss either side, even as it leans towards Karisa���s generational skepticism and his grandmother���s plight. Without a clear narrator, the film also does not seek to answer the broader question about witchcraft in contemporary Kenya. Rather it exposes how witchcraft is more importantly a spiritual/supernatural manifestation of everyday misfortune.

Still from The Letter.

Still from The Letter.For an East African audience, The Letter will likely resonate with the generational and spiritual debates, which often clash within families spread across rural/urban and class divides. For teachers, this documentary will spark rich class discussion and provide an empathetic look at contested traditions many students simply dismiss.

As a scholar of Kenyan history, I would have liked to see the film contextualize the gendered and generational debates more. For instance, even as Karisa challenges traditional elder patriarchal authority he also tells us that ���In the family there are those fundamental people you respect like your uncles. Whatever he���s been telling you he is the backbone of the family. So, when he tells you someone is a witch ��� you will believe because he���s the elder.��� This gendered generational and class debate is implied but not fully addressed in the film as Karisa���s educated and urban aunties challenge more traditional, rural forms of patriarchy. However, these points are minor distractions from the excellent work Lekow and King have put into their film. The Letter is certainly worthy of distribution beyond the film festival circuit. I hope to see it in a popular streaming service soon.

February 22, 2020

Point of order

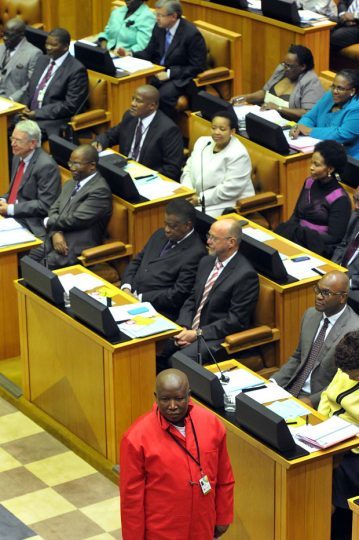

Julius Malema swearing in to Parliament. Image via Government of South Africa Flickr CC.

The annual State of the Nation (SONA) address by South Africa���s president has become a predictable spectacle. South Africans now expect at the very least a disruption of proceedings by some MP’s (at various times, MP’s from the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters have interrupted proceedings or walked out), and at worst fighting between MP’s and parliamentary security (as the EFF has done too). In all of this, the media has been locked in a symbiotic relationship with politicians, as the latter tries to wrestle open a space for themselves on screens, streams and front pages. The EFF, the third largest party in parliament, have become masters at this game.

This week the EFF was handed a victory from an unexpected quarter ��� a former apartheid President who, until this week, occupied a marginal place in the post-apartheid South African political landscape.

As President Cyril Ramaphosa was getting ready to deliver his SONA address, EFF leader Julius Malema rose to raise a point of order: The EFF insisted Ramaphosa could not proceed with his SONA speech until F.W. De Klerk, who was a guest of parliament, had left the chamber. De Klerk served as Mandela���s deputy in the new ���government of national unity��� after 1994 (he was one of two deputy presidents, along with Thabo Mbeki), but he was also the last white president of apartheid South Africa. More importantly, De Klerk has been an apologist for apartheid: on a number of occasions, he has denied that apartheid was a crime against humanity. And as recent as 2012, D Klerk told Christiane Amanpour of CNN, in an interview, that apartheid had been beneficial to its black victims. The EFF also resents De Klerk for not owning up to the actions of government death squads while he was President. The EFF felt it was an insult to South Africans that he was a guest of parliament.

The EFF���s points of order went on for about two hours. At first it seemed like business as usual���for some, all part of the EFF���s tactics to disrupt proceedings and deflect the spotlight away from their own problems, such as the allegations of corruption at VBS Bank, which ensnared the EFF. Eventually the EFF left the chamber. Outside the chamber, journalists shoved microphones in ANC leaders��� facing, demanding to know why they did not support Malema���s demand. The ANC spokespeople (we saw ANC spokesperson Zizi Khoza and the party���s general secretary Ace Magashule) who had microphones pushed in their faces, talked about reconciliation and that De Klerk as a former deputy president after apartheid, was entitled to the courtesy of attending SONA. With the EFF gone, Ramaphosa could continue with what was, in any event, considered to be a lackluster speech. Most people can���t remember what he talked about.

Mainstream commentary initially condemned and ridiculed the EFF���s antics. One reason was that very few people in South Africa care these days what De Klerk does or thinks. He is retired from politics and runs a foundation in his name, that promotes center right political positions and occasionally releases reactionary statements on affirmative action, land reform or democracy, while he makes money on the speaker���s circuit.

It was the media snowball that grew bigger and bigger in the hours and days after SONA that eventually became the most significant result.

When the Speaker, after a myriad EFF ���points of order��� adjourned Parliament and party spokespeople joined the media in the scrum outside, reporters picked up on the EFF���s talking point: Why didn���t you support Malema���s call for De Klerk to be ejected from the visitors��� gallery? It was clear: the EFF had already managed to set the media���s agenda for them. But even then, it didn���t seem like the EFF had scored any political points. De Klerk appeared to serve as a convenient target for the EFF���s shenanigans during SONA itself. That seemed to be it for this point of order.

What the ANC and media commentators (as well as the EFF) had not anticipated, was that De Klerk would issue a statement the next day that unmasked his unapologetic stance about apartheid and unleashed a national backlash. De Klerk now doubled down on his insistence that apartheid was not a crime against humanity and dismissed it as ���Soviet propaganda.��� In doing so, he turned what had been a sideshow into the top story.

De Klerk���s tone-deaf response led to a nationwide outcry and ensured that the EFF dominate the media agenda for a whole week and score some political points in the process. A first analysis of social media trends shows the EFF steered online conversations too. Suddenly the EFF was in control of the national narrative, despite the widespread repulsion at their disruptive behavior and racist attacks on political opponents.

By the evening of that same day, De Klerk backtracked on his defense of apartheid. Mainstream write-ups gave credit to Desmond and Leah Tutu for rebuking De Klerk and leading to his about-turn. But this was another example of how well the EFF manages to play the media game. The winner in this whole saga is the EFF.

The EFF���s seemingly puerile disruption forced De Klerk to backtrack on something he has refused to do the last 25 or so years. The EFF could claim that it had started the process that embarrassed De Klerk and exposed him as an unrepentant racist. Who now remembers what plans or policies President Ramaphosa had for South Africa? His speech fades into obscurity except for policy wonks. Which is a shame. Very few people care what De Klerk think these days, but now he was thrust into the center of media controversy and became the barometer of race relations and white racism in South Africa.

As a form of electioneering by the EFF it makes the ANC seem incapable, indecisive and unwilling to take on racism or white supremacy head-on.

What do we learn from this? The EFF, probably more than any other party in South Africa, understands that politics is increasingly mediated, even in a country where voting still largely takes place along race and class lines. They have exploited this very well from the get go: the semiotics of dress (red overalls, berets, their language), strategic walkouts and disruptions at SONA, and the charisma of Malema have captured public attention despite the EFF playing fast and loose with poor people���s aspirations.

For this to work, the EFF needed the media to take the bait, and the media obliged. Under President Jacob Zuma, Malema and his rowdy comrades were a proxy for the questions the media wanted to ask Zuma. The EFF also articulated the nation’s frustrations with an increasingly unaccountable and impenetrable ruling party at the time. Despite their antagonism towards the media (demonstrated a decade ago already when Malema chased out the ���bloody agent��� from the BBC, and Malema���s deputy, Floyd Shivambu���s 2018 attack on a media photographer), the EFF remains successful in commanding media attention at every turn, benefiting even from negative coverage.

This does not mean that they are liked. It is widely understood that these tactics are aimed at deflecting attention away from their own scandals. During the post-SONA debate, Malema used gender-based violence to score cheap political points. (He accused Ramaphosa of beating his wife). This was rightly been seen as beyond the pale. (It is ironic that when the ANC MP���s accused Malema of the same thing, he threatened to sue one of them and walked out of parliament in a huff.)

South African politics is now highly mediated (playing out on social media) and strikingly visual (defined by the politics of spectacle). Insisting that parliament returns to a cool, calm and collected rational debate is unlikely to change this style of politics. Like elsewhere in the world, populist politicians like Malema command the media���s attention even as they criticize and revile them. How ironic then that the last white leader of a minority racist regime was the one who ensured a victory for the EFF. And, irony upon irony, these deflection tactics are peddled by a party claiming to represent the poor and the workers, to further their own interests. They have just emphasized the need for a true democratic socialist alternative and a more proactive rather than a reactive media.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers