Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 187

March 17, 2020

Reading List: Jill Kelly

Climate change protest in Durban, South Africa. Image credit Ainhoa Goma for Oxfam via Flickr CC.

I thought extensively about Inkosi Mhlabunzima Maphumulo for my first book, To Swim with Crocodiles: Land, Violence, and Belonging in South Africa, 1800-1996 (Michigan State University Press and University of KwaZulu-Natal Press). As I consider the lives of several overlooked African women leaders for a new project on women and anti-apartheid activities in 1950s rural KwaZulu-Natal, I���ve been reading a lot of biographical work.

Sibongiseni Mkhize���s Principle and Pragmatism in the Liberation Struggle is a political biography of Selby Msimang. Born to land-owning farmers in Edendale, Msimang was a founding member of the African National Congress (ANC), an office-bearer in the multi-racial, anti-communist Liberal Party, and a founding member of the Zulu nationalist Inkatha Yenkululeko Yesizwe in the days it was still connected to the ANC. Mkhize���s focus on ���principle and pragmatism��� brings coherence to a political leader whose career spanned the 20th century and whose varied allegiances can at times appear erratic. Msimang remained dedicated to economic empowerment and the protection of black land owners; he was firmly anti-communist. The recent battles between the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal and the national ANC over the presidency hang over the book, as Mkhize shows when Msimang���s willingness to hang back enabled transformations in regional and national politics in 1951, making way for an ascendant Chief Albert Luthuli. As Luthuli expressed a willingness to work with communists, Msimang joined the Liberal Party and then, upon its disbandment (rather than defy new legislation against interracial politics), Inkatha. Mkhize���s biography stands out for its attention to a leader that lacks an ���unbroken record of commitment to the ANC.���

South Africa���s HSRC Press Voices of Liberation series brings together analytical essays with the texts of important thinkers who shaped South Africa���s liberation struggle. Shireen Hassim���s Fatima Meer: A Free Mind became the second in the series on a woman. Hassim thus offers a resolutely political and intellectual biography of the scholar-activist who, when she was appointed in 1956, became the first black woman to hold an academic position at a white university in South Africa. Hassim shows Meer to be ���driven by an activist sociology for a common society, by a rage against injustice and by a profound belief in the value and capacity for research to convince the powerful of the consequences of their choices.��� The first woman to be banned, her political consciousness spread from Gandhism into non-racialism and Black Consciousness. Among other things, Meer thought deeply and published widely on Indians in a manner that embeds them in South Africa, rather than conceiving of them in liminal spaces. She established an independent publishing entity and research institutes to train black researchers and writers. She embraced biography herself, telling then suppressed stories of Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, and Andrew Zondo, the Mkhonto we Sizwe soldier. This publication makes available some of the materials of Meer���s archive���from her published and unpublished research to speeches and her impressions of the US.

(I���m also excited about Bongani Nyoka���s discussion of the influences on and legacies of Archie Mafeje in the same series, but haven���t sat down with it yet).

Hassim���s study of Meer and Holly McGee���s Radical Antiapartheid Internationalism and Exile: The Life of Elizabeth Mafeking contribute to the increasing biographical work on women political actors in and around the Congress movement. In 1959, Elizabeth Mafeking captured the attention of the world, escaping apartheid South Africa without ten of her eleven children whom she would work to smuggle out to join her. Mafeking was the President of the African Food and Canning Workers��� Union and the National Vice President of the ANC���s Women League. She traveled the country organizing workers and in 1955 posed as a nursemaid to leave the country for the World Conference of Workers in Bulgaria, where she spoke out against apartheid. After touring collective farms in China and witnessing workers organizing in the Soviet Union, she returned home to aggressive state surveillance. The apartheid government named her ���the most dangerous threat to native administration in the Cape��� to justify her banishment 600 miles from her home. She escaped to a decolonizing Basutoland, where she unknowingly became the subject of a diplomatic quandary as the British considered the liability of South African refugees in Basutoland. Drawing on archives in South Africa, Lesotho, the United States, and recently declassified British Commonwealth Relations Office records as well as extensive oral histories with Mafeking���s family, McGee illuminates the life of Mafeking, from her trade unionism and self-imposed exile and back, considering how the union and women���s leader purposefully utilized motherhood as a political tool to undermine the state���s positioning of African motherhood as irrelevant. In her attention to letters and oral histories, McGee sensitively tells the story of a woman activist and her exiled family.

McGee situates Mafeking within international networks in which women promoted black nationalist causes���akin to the women of Keisha Blain���s award-winning Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. Blain demonstrates the leading role of black nationalist women in the US, Jamaica, England, and West Africa in the era between the 1920s of Garvey and the Black Power movement of the 1960s. Blain pieces together the lives of women who did not leave archives, showing how the post-Garvey moment opened space for women to engage in black nationalist activism in new and innovative ways and on their own terms. Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, a Chicago Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) leader, launched the Peace Movement of Ethiopia, the largest black nationalist organization established by a woman in the US. Gordon and a number of other black nationalist women organized others in support of a back-to-Africa emigration project, maintaining a global racial consciousness and pursuing paradoxical but pragmatic alliances, such as with the white supremacist Senator Theodore Bilbo from Mississippi in support of the Greater Liberia Bill to fund emigration to Liberia. Blain analyzes these women���s principles and actions with great nuance, positioning them as proto-feminists who challenged patriarchal structures, but who were also complicit in promoting patriarchal visions of black liberation. They were committed to anti-colonialism and pan-Africanism yet subscribed to the belief that emigration would enable racial uplift on the continent. Notably, Blain brings African and African-based women, such as Adelaide Casely Hayford, into diasporic histories of Garveyism.

March 12, 2020

Letters of resistance

Weaving in Ethiopia. Image credit mo2she via Flickr CC.

In 1882 Mame Yoko Gbahnyer, Mame Maroogbah, and Mame Bandawah of Senehun (present day Sierra Leone) wrote a letter to the colonial government in Freetown. Yoko in particular was remarkable for her time. She was a local leader after her husband, Gbahnya, the local chief asked for Yoko to be his successor while on his deathbed. (Mame Yoko and Mame Maroogbah were co-wives, and Bandawah was Yoko���s sister-in-law.)

The letter concerned a dispute about a trader who had been attacked in their region. The letter begins, ���The women of Senehoo desire to show the interest they have always taken in the affairs of the country since the death of the Chief,��� and continues to assure the colonial government that they will deal with the matter by arresting the person who attacked the trader.

Further south, in 1926, Baboni Khama, Mmakgama Khama, Milly Khama, and Oratile Sekgoma, all from Botswana���s royal family, wrote a letter to the High Commissioner contesting the leadership of the regent Tshekedi Khama on the grounds that he was withholding their inheritance as a way of consolidating his power. In 1934, members of the Anglican Mother���s Union in Uganda���Lusi Kafero, Everini Segobe, Tabisa Sonko, and Naomi M. Binaisa���wrote a letter to the Bishop contesting the appointment of a certain Mr. N. Senkonyo ���to head the bigger and more important subcounty of Sabawali in Kyagwe County��� because he had appeared in court for domestic abuse. In 1946 Huda Shaarawi wrote a letter to the Prime Minister in her capacity as the founder of the Egyptian Feminist Union (EFU), making a case for women���s rights in Egypt.

These letters, all included in the anthology series Women Writing Africa, demonstrate how women from the 18th to the 20th century lobbied powerful structures such as colonial governments, the church, and the state in order to address their concerns. They are evidence of the myriad ways women have participated in political and public discourse. Finally, they offer clues about how women have used writing to not only resist power but to imagine the kind of world they want.

Edited by a group of prominent feminist researchers including Fatima Sadiqi, Amandina Lihamba, Esi Sutherland-Addy and Margaret Daymond, Women Writing Africa constitutes and makes available one of the most extensive pan-African archives of women���s writing on the continent. The series is ordered geographically, with volumes collecting material from East Africa, North Africa, Southern Africa, West Africa and the Sahel. The letters mentioned above appear among a variety of other texts such as songs, extracts from stories, folklore, speeches, and essays, and as such, capture a broad range of women���s perspectives. The songs offer an example of oral history and cross-generational transmission of knowledge.

The earliest text featured in the series dates back to 13th century CE: two songs from Mali composed by Sogolon Konde honoring her son Sunjita Ke��ta (Emperor of Mali: 1235-1255), preserved by historian Adama B�� Konar��. The story of Sogolon Kone and her son Sunjita Ke��ta is one that I first encountered through this text. This story highlights the connection between oral history, contemporary culture and the archive as the editors explain that the songs have been ���remembered throughout the ages and are part of popular culture of contemporary Mali.��� The anthologies also challenge the silences about women as rulers in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries in spite of the incomplete historical record from this era. The first text in the Eastern Region anthology responds to this as it is another letter attributed to Sultan Fatima binti Muhammad Mkubwa who was a ruler of Kilwa, off the coast of present-day Tanzania. The letter was written by a scribe in Arabic text in 1711 and the content of the letter suggests the kind of diplomacy that rulers used to form alliances. Similarly, the first text in the Northern Region anthology is an inscription by 15th century Pharoah, Hatshepsut, which was translated from hieroglyphics.

The work of preserving (and in some cases translating) these texts and bringing them to a wider audience in the form of this anthology is an important contribution that highlights how feminist scholarship can challenge epistemic injustice. Too much of the scholarship on African intellectual production focuses on essays and speeches���traditionally forms available to men, and particularly to men afforded colonial educations. The focus on other forms in this anthology enriches our history with stories from mothers and grandmothers who elude the historiography of ���great men.��� And while translating some of the texts into English from indigenous languages may sacrifice some of the flavor of the originals, the translation allows for wider engagement and access.

This process of mining the archive for women���s writing reminds me of a concept in isiXhosa called ukuzilanda. Literally meaning ���to fetch oneself,��� it is a concept that encompasses practices and rituals through which people bring the past into conversation with their present reality. A common example is reciting family names (iziduko in isiXhosa) when introducing oneself to new people. The list of family names locates one as part of a longer lineage and history, bringing that history to bear on the present. By focusing on women���s letters and other forms of literature, as Women Writing Africa does, the anthologies become an invitation for a kind of matrilineal ukuzilanda. Though it seems ironic that this work is necessary, given that our mothers and grandmothers are the people who give us our first language.

March 11, 2020

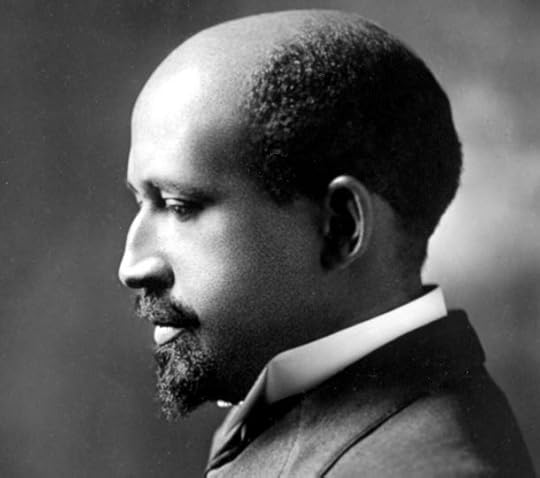

Du Bois in Berlin

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

As Kwame Anthony Appiah cites several times in his book Lines of Descent: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity (2014), Du Bois liked to quip, when asked how to define Blackness, that ���The black man is a person who must ride ���Jim Crow��� in Georgia.���

The appeal of this anecdote is its wry pithiness, which stands in contrast to the enormous political and intellectual energy Du Bois dedicated to the question of race. It was a lifelong project. But Appiah identifies 1892 as being particularly important in the development of Du Bois���s thinking. In July of that year, Du Bois boarded a steamship to Europe, where he would study at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit��t (what is today Humboldt University) in Berlin. His semester didn���t begin until late October, so he took his time with stops in Rotterdam, D��sseldorf, Frankfurt, Cologne, and elsewhere. To be on a fellowship in Europe was prestigious. To be in Germany specifically was to be exposed to an intellectual vanguard of the time. Du Bois had received his bachelor���s degree from Fisk University, a historically Black institution in Nashville, Tennessee, and he went on to earn a second bachelor���s degree and MA in history at Harvard. The plan was to complete his PhD in Germany, though he ultimately left without a degree due to residency requirements. He went on to become the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University.

Appiah recounts this brief, but formative, period in Lines of Descent with the purpose of discerning the intellectual wellspring of Du Bois���s later writings on race, Pan-Africanism, and the Black experience more generally in such works as ���The Conservation of Races��� (1897), The Souls of Black Folk (1903), and Dusk of Dawn (1940). His prolific scholarship and his range of political commitments���including his attendance of the Pan-African Conference in London (1900); cofounding the Niagara Movement (1905); cofounding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909); and co-organizing the series of Pan-African Congresses beginning in 1919���have defined what it means to be an activist-intellectual. Appiah argues that this longevity of involvement reflects the lessons Du Bois internalized while studying in Berlin.

More specifically, his German education illuminates the sources of his race-thinking and its turn against scientific reason of the time to a sociohistorical understanding. In Appiah���s words, ���Du Bois was America���s last romantic��� [his] arguments were tethered to the varieties of racial romanticism and postromantic thought that he took from Germany���s intellectual traditions; they were kin to the ideas through which Germany sought to define itself as a nation among nations.���

Du Bois���s fascination with Germany was not unusual���several of his professors at Harvard, including William James and George Santayana, had either studied or spent meaningful time there. However, unlike his teachers and white peers, his time in Berlin gave him his first experience of freedom from American racism. His two years in Germany enabled him to see the American situation of race from a removed standpoint���a condition of racial exile similar to that pursued later on by Richard Wright and James Baldwin, who lived as expatriates in France. Though European racism was not absent, Du Bois had a freedom of mind and body he would experience in only limited ways in the future, including visits to Liberia, Sierra Leone, Senegal, the Soviet Union, China, and eventually Ghana. ���Germany was the first place where Du Bois experienced life without the daily cruelties and public insults of racism,��� Appiah remarks. Du Bois himself, as quoted by Appiah, more plainly stated, ���this was the land where I first met white folk who treated me as a human being.���

Du Bois also encountered a vibrant intellectual milieu, one that sought to produce academic knowledge with political implications. The industrialization of Europe during the nineteenth century had created social and economic inequalities across the continent that drew the scrutiny of scholars. Gustav von Schmoller, an economic historian and founder of the Verein f��r Sozialpolitik (Association for Social Policy), was one of Du Bois���s teachers who believed that scholarship could be ���both dispassionate and engaged.��� As Appiah further elaborates, Schmoller and his colleagues ���didn���t think that the ethical could be excluded from historical studies, not least because the development of the ethical was itself a historical phenomenon.��� This proactive approach and its effect on Du Bois would later gain expression in The Philadelphia Negro (1899), Du Bois���s first work of sociology, in which he wrote with power and without hesitation:

If in the hey-dey of the greatest of the world���s civilizations, it is possible for one people ruthlessly to steal another, drag them helpless across the water, enslave them, debauch them, and then slowly murder them by economic and social exclusion until they disappear from the face of the earth���if the consummation of such a crime be possible in the twentieth century, then our civilization is vain and the republic is a mockery and a farce.

Du Bois consequently grasped how the ���Social Question��� (Soziale Frage) in Germany could inform the ���Negro Question��� (Neger-frage) in the US���not only in terms of framework, but in terms of analysis. Schmoller and other members of the Verein were critical of ideas that attributed social progress to either ���timeless natural laws��� or the result of pure individualism���positions held by members of the emergent Austrian School of economics, which would go on to influence neoliberal policies of the late twentieth century. For Schmoller and those aligned with him, social classes and communities mattered. Political pressure and state responsibility were equally indispensable. This critical historicism intersected with Du Bois���s concurrent embrace of an earlier set of thinkers associated with German Romanticism���in particular, Johann Gottfried Herder, whose concept of the spiritual character of nations (Volkgeist) deeply impacted his thinking. The notions of ���striving��� (streben) and ���soul��� (geist) would later surface in The Souls of Black Folk. This intellectual eclecticism further contributed to the stylistic blending of the personal and the social in Du Bois���s writing, which Appiah describes as his signature combination of ���soaring, rhapsodic poeticism and dry, assiduous empiricism.��� It also informs the tension between explaining social facts and understanding subjective experience as tacitly captured in Du Bois���s forceful question from The Souls of Black Folk: ���How does it feel to be a problem?���

These intellectual influences Du Bois encountered in Berlin ultimately contributed to his sociohistorical definition of race, which was positioned against the scientific reason of the time. He was not alone in his belief that there was no correspondence between race and mental aptitude. Franz Boas, the German-born anthropologist whose work demonstrated his own antiracism, had left for the United States from Berlin only a few years before Du Bois arrived. Du Bois later invited him to deliver a commencement address at Atlanta University in 1906, after Boas had become a professor at Columbia University and Du Bois had attained a professorship at Atlanta. Beyond agreement on the pseudoscience of race, both were united on the issue of culture. As Appiah writes, ���cultural transmission��� became a central feature of Du Bois���s approach to race. But more than this was the role of politics. Appiah addresses how Du Bois���s recurrent engagement with race and its definition did not exclusively comprise ���an attempt to reflect the existing reality of race��� but also constituted ���an attempt to call his own race to action.��� ���Du Bois moved on from the biology and the anthropology of the nineteenth century,��� Appiah concludes, ���but he never left its world of idealistic ethical nationalism.���

Appiah ends Lines of Descent by maintaining that the academic debates and intellectual traditions of Germany continued to influence Du Bois���s thinking. By extension, they have continued to have bearing on our approaches to race in the present. It is worth mentioning that there are curious omissions in Appiah���s discussion. The Berlin Conference (1884-85) and Germany���s colonies in Africa are missing, leaving uncertain how Du Bois felt and responded to this larger political context while in Berlin. German thinkers who go underexamined or unexamined entirely include Georg W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Du Bois���s promotion of an elite ���Talented Tenth��� to lead the African-American community can be interpreted as echoing Nietzsche���s idea of the ��bermensch. Marx had a more conspicuous imprint, as seen in the Marxist analysis of Black Reconstruction (1935), Du Bois���s travels to the Soviet Union beginning in 1926, and his eventual membership in the communist party at the end of his life. Hegel���s racism toward Africa is touched upon too briefly.

Nonetheless, Appiah���s argument for the cosmopolitanism of Du Bois���s education and how it informed his project of defining Blackness without resorting to monocausal explanations of science, history, culture, or political status remains significant. As Appiah���s title insinuates, the color line was not the only line to influence Du Bois���s thinking. The method of social constructionism that Du Bois pioneered was the result of his engaged research imagination and his creative interweaving of multiple intellectual strands. As with Pan-Africanism, academic ideas and the narratives that emerged from their exchange could ���bind people together,��� granting Du Bois a world and freedom of mind he would not have experienced otherwise.

March 10, 2020

The Blitzboks in America

Image credit Mike Lee, KLC photos for World Rugby.

The United States and South Africa faced off in the quarterfinals of the Los Angeles leg (the ���LA 7s���) of the World Rugby HSBC Sevens Series on March 1, 2020. In addition to the play on the pitch, the match revealed a great deal about the rugby cultures in both countries.

The mise en scene itself embodied America. Loud, brash, kinda drunk, fundamentally friendly yet periodically xenophobic, a bit ignorant, and geared toward spending $$$. And with $9 bottles of water, $20 plates of tacos, $15 cans of beer, and $70 hoodies, it was really easy to spend $$$; suffice it to say the exchange rate to South African Rands was horrifying. But Americans are also pretty good at hosting sports. Dignity Health Sports Park, a facility that usually hosts the LA Galaxy Major League Soccer team (and for the last three years the vagabond LA nee San Diego Chargers of the NFL) is quite a fine venue to watch a sporting event.

Fans from all over the world���mostly expats who have found their way to America and the sprawling expanses of Los Angeles���descended and supported their side. The crowd at the stadium was diverse because Fiji���s raucous fans arrived in droves, Kenya had a large fan base, and Samoans, Koreans, and other fans were in attendance as well. Among these were considerable numbers of South Africans, almost every one of whom I spoke to had moved to Southern California some time ago, and almost all of whom were white. The only black South Africans I saw manned a booth clearly geared toward drawing tourists to Mzansi. In South Africa, the game is diversifying (has always, in fact been diverse, but was developed separately, as it were, under apartheid) but the fan base in LA reminded one that South Africa is deeply stratified by race but also by class. I did not want to impose on those I spoke to casually, but of every South African I met, I wanted to ask: When did you move to the US?

The South Africans I did ask about their arrival in the US had a range of answers, but if they looked over the age of 40 they almost universally told me they had been here for some version of ���a bit more than twenty-five years.��� There is a reason why white South Africans were leaving South Africa about twenty-five years ago, and those are not always virtuous reasons. Among the younger ones, and there were a lot, answers varied���some came across with their parents when they were young, a few were here for work or school, and some were here ���on holiday.���

The fans festooned in the red, white, and blue of the United States too were overwhelmingly white. This is not surprising, as rugby in the United States is a middle class sport played (when played at all, that is) overwhelmingly by suburban kids who may not play football or basketball.

On the pitch the two sides emphasized different things. For South Africa, the Blitzboks have been formidable internationally, winning three World Series titles (including two in a row in 2016-17 and 2017-18) and finishing runners-up seven times. The US has a sole 2nd place finish, which they accomplished in 2018-19. Head- to-head, the two sides have met 57 times in sevens. The Blitzboks have won 50 of those meetings.

Nonetheless, for the Americans, because they have had a modicum of success, sevens rugby is seen as a priority, a way the US can compete in a way that they never really have, despite some clear steps forward in recent years, in the traditional 15-player game of rugby union. The inclusion of sevens rugby in the Olympics further validates the emphasis on the sport in American rugby circles.

For South Africa, sevens is growing in line with the HSBC Sevens Series, but it is still just a sideshow to the Springboks and Super Rugby and Currie Cup and all of the other iterations of the international union game in which South Africa is one of the best. Sevens in South Africa is still a developmental game, a game for guys who may not be quite up to the demands of union, or of guys better suited to the sevens series than to, say, Super Rugby, which overlaps with the back half of the Sevens Series. Put another way, few South African players who could star in Super Rugby or in one of Europe���s top leagues would necessarily choose to remain contracted to the Blitzboks. This is not to say that there are not exceptions. But generally speaking, Blitzboks graduate to professional fifteens if they can do so. None of this is to denigrate sevens rugby or its players���sevens is a different game from union, far more wide open, far faster. Half of any given union team would have no position in sevens, and many of the aspects that are central to union���most notably the importance of set pieces���are just not as significant in the shorter game. They are variations of the same sport, to be sure, but they are not the same sport, and skill in one does not necessarily translate to comparable mastery of the other.

On the pitch the USA-Blitzbok match was a good one, by far the closest of the four quarterfinal matches. The US stormed out to a 10-0 lead on two Carlin Isles tries but the Blitzboks got one back when Ryan Oosthuizen crossed after snagging a pass out of the air that was not intended for him. Confirmation of the try required a consultation with the TMO, and to be honest it really did look like he lost possession before grounding the ball, but it held up on replay. The score-line read 10-5 at the half, as both teams missed their conversions, a fact that would especially haunt the Americans when the final hooter blew. The teams battled in the second half, with time beginning to favor the US, but in the last minute South Africa won possession and JC Pretorius scored a last-minute try. Selvyn Davids converted, and the US could not get anything going before South Africa forced a turnover, kicked into touch, and set itself up for a semifinal match against current season log leaders and historic South African rugby foes New Zealand. The United States ended up defeating Ireland for a respectable 5th place finish overall.

In the semis against the All Black 7s (which the Blitzboks won handily in a 17-0 whitewash over their ancient rivals) a loud ���Bokke��� chant broke out, and my fan���s ambivalence about South African rugby re-emerged. There is, I must say, nothing wrong with Afrikaans, the language of the Boers, of Afrikaner nationalists, sure, but also the language of coloured South Africans and one of South Africa���s eleven official languages in the post-apartheid era. But at the same time Afrikaans chants at rugby matches since 1992 have a long and sometimes ugly history that ties into not only the fraught politics of language, but also to a fetishization of the old apartheid flag (none of which, it must be said, were on display in Los Angeles) and of the Springbok logo, which seems redolent of recidivist white nationalism. Perhaps this is not fair, of course���sometimes a ���Bokke��� chant is just a ���Bokke��� chant���and it may speak to my own bigotry. But rampant Afrikaner pride at rugby matches always makes me uneasy and there are historically legitimate reasons for this even if for this mass of expats the chants were probably completely anodyne (and I doubt that the group acted with one motivation in any case).

But there was always the possibility of a tell, a sign that gave away the true intention. For at the World Rugby Sevens Series, they only play national anthems for the final match, the Cup Championship. And so when South Africa made the finals and they played ���Nkosi Sikilele Africa,��� I listened. And sure enough the tell came clear���anyone who has been to a Springbok match knows what I am talking about���the song switches to Afrikaans and suddenly white fans find their voice, singing the remnants of the old national anthem ���Die Stem��� full-throatily. And it isn���t 1995 anymore���if a South African does not know all of the lyrics to the full national anthem by now, they don���t want to. The Afrikaans lyrics did not ring as loudly as the ���Bokke��� chants (so we cannot draw a straight line conclusion between what one but not the other means), but they rang through loudly enough.

The Blitzboks got blitzed in the first half of the finals against a rampant Fiji squad that has not been quite as formidable this year as in years past but that all weekend showed why they might be the most dangerous team in sevens rugby even as they entered the weekend in an uncharacteristic 5th place. It was 19-7 at the half, but that score-line flattered to deceive the Lightning Boks, who needed a try after the clock had expired just to get on the board. But the Blitzboks fought like hell in the second half and another try after the hooter (by Bronco du Preez) followed by a long conversion at a tough angle by Selvyn Davids and the championship game went to sudden death. In that extra time the Boks took advantage early and when Sakoyisa Makata went over for the winning try, the Blitzboks were the tournament champions and crawled closer to leaders New Zealand on the series table.

Victory assured, the Saffies in the crowd got to sing ���Ole,��� and chant ���Bokke,��� and I suppose sing Die Stem to their hearts content while wrapped in the new South African flag. Being the fan of a champion absolves a lot of sins. It also abnegates any need for self-reflection.

March 9, 2020

The untold story of the making of South Africa

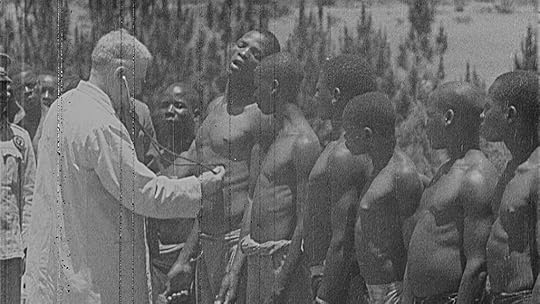

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.

A few short years into the age of the camera drone, the fly-over is already a documentary film clich��. It is therefore testament to both the surrealism of the southern African mining industry and to the visual sophistication of South African Catherine Meyburgh and Namibian Richard Pakleppa���s Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa that the opening shot is so profoundly disturbing: From mostly empty veldt, the camera creeps over the fortress-like wall of an East Rand mine operation. The unfolding complex appears as a tidy penitentiary. A miner���s disembodied voice confirms that this category confusion will be the animating spirit of the ensuing film: ���A mine,��� he says, ���is a prison.���

Indeed, the narrative arc of Dying for Gold is the unpacking of that simple premise at multiple scales. For over 90 minutes, the camera travels across southern Africa, drops into the dark, dangerous tunnels, and wanders more than a century of archives. The goal, according to Meyburgh���s voice over, is ���to start to understand the real cost of gold in our lives today.��� There is nothing subtle or surprising in the message. But deft cinematic storytelling makes Dying for Gold surprisingly nimble for an advocacy film. It brings to the familiar story of mining a remarkable portrait of those trapped in the industry���s cage.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.Formally, Dying for Gold is a m��lange. The film tacks between original and archival footage: environmental shots of downtown Johannesburg, leafy suburbs, rural villages, and train stations���all interspersed with state propaganda, newsreels, and pop culture visions of the mines and the lifestyles they enabled. The images bounce from the 1920s to the present, often paired with readings from mine company and government communiques. Dates rarely match, but together the text and image couplings explore common themes. They make clear that the need for black bodies to work the mines, and the devastation done to those bodies and lives, has changed little since the Witwatersrand Gold Rush.

One of the most powerful of these mashups comes roughly twenty minutes into the film. A voice reads excerpts from a 1903 commission of inquiry into the labor requirements of South Africa���s expanding mine and agriculture sector. The principle threat to the economy, the voice states baldly, is that ���the African native tribes are in possession of large areas of land.��� Played over scenes from the 1940s film Matsela, in which a helpful friend advises the fictional title character to leave his mountain village for the mines below, the narrator drones on. ���A great modification of these conditions��� of land ownership must be enacted, according to the commission. ���[T]he proposals put forward to improve the supply of natives recommends that the existing native social system should be attacked with the object of modifying or destroying it.��� While the machinations that drove thousands of laborers into the mines are no secret, there is chilling poignancy in seeing that story told simultaneously over two decades, at macro and micro scale, and in both fact and fiction.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.Original interviews with miners and their families across South Africa, Mozambique, Swaziland, and Lesotho then form blocks that separate these archival collages, illustrating in fine detail the inescapable traps that mining set throughout the ���native social system.��� The Manyokole family of Lesotho is a case in point. Liao Manyokole is a young man who travels to South Africa for extended stints underground, while Matisetso, his wife, works as a sharecropper on land they do not own. She makes enough to eat, but not enough to pay their debts. Liao���s father Mohau was a miner until lung disease allowed the company to release him, without support, from his contract. Every night, his daughter-in-law says, Mohau lay in bed, trapped and suffocating in the ruins of his own body. His wife Mamatselio was in turn imprisoned by her relationship to a dying husband. When he finally passed, Liao borrowed money from the mining firm for his father���s funeral, trapping the entire family in indenture. As Liao recounts the pride in being passed to manhood through initiation, finally able to earn money like a man, masculinity itself reads as a death sentence. The mining economy imprisons everyone, though the terrible beauty of the film is its effectiveness in capturing how mining imprisons each protagonist in a unique way.

There is a good deal of stylized visual work in these interviews. Colors are lushly rendered and the frame holds for long seconds on individuals and family groups posing for portraits in rural settings poignantly devoid of other people. Subjects routinely stand with their backs to the camera, looking out at empty fields, depopulated mountains, and vast skyscapes. Such deliberate visual work reinforces one of the more interesting archival discoveries in the film, one that ties the interview segments to the historical samplings: mining companies and their state allies saw film as a tool for sustaining the mining economy.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.

Still from Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa.The cinematic trap is literally set in a series of memoranda exchanged in the 1920s among officials of the Native Recruiting Corporation. Mr. C.G. Taylor, district manager in Vryheid, writes to his bosses that he is ���of the opinion that meetings and mere talk of the work of the gold mine are not sufficiently impressive, nor lasting enough on the native mind.��� What is called for is the creative use of the ���open air cinematograph.��� To get them to the mines, the natives need movies���depictions of the modern city of Johannesburg, the money to be made, the vast housing compounds, and the ���comfort and safety of mining.��� White South Africans, too, are trapped in a kind of image cage. A more pleasant one to be sure, but no less phantasmatic. South Africa as it appears in government and popular film across the decades is a prosperous land, a place of racial harmony, a healthy mix of industry and leisure that benefits everyone���though admittedly white South Africans appreciate it more. The camera may not have been the most important weapon for dispossessing Black labor of its land and ���modifying or destroying��� the social system, but it was certainly a powerful one. And Dying for Gold is a richer film for effectively using the camera to make that point.

Ironically, the film���s effectiveness at avoiding the visual clich��s of contemporary documentary and the easy outrage tropes of activist filmmaking make the final moments of the film among the weakest. Dying for Gold ends with a pitch for support for the half million South African miners demanding just compensation for their work, in part through a class action lawsuit against the major mining companies. As the drone once again flies over South Africa���massive slag heap, urban center, township���Meyburgh concludes that it would be too easy to point fingers at the mining companies and the state. The archives, she intones, are shocking ���because all of us who benefit from this economy are complicit.��� This is undoubtedly true. But if Dying for Gold has shown us anything, it is the strategic cynicism of the world created by those who built the mining economy and the state that supported it. We may all be complicit, just as we may all be trapped. But the burden of mine work is differentially distributed. Dying for Gold is compelling evidence that we still need justice.

March 8, 2020

The ���abnormality��� of Cape Town���s traditional carnival

Cape Town Carnival. Image credit and copyright John Edwin Mason, used with permission, not for reuse.

The month of January has a peculiar character for the city of Cape Town in South Africa. It is peak carnival season. Yet, in this time of celebration, public discourse about carnival conveys a sense that it is abnormal, as if it does not meet expectations; that it is both a laudable tradition of the poorest in the city, and yet also something distasteful, to be tolerated at best. This enigmatic feeling says something about our racialized past and complicated present. The traditional carnival, or klopse, to use a vernacular term���often casually associated in public discussion with petty gangsters, organized crime, and the ever-controversial blackface���remains profoundly abnormal, out of sync with the city���s fashionable global image. It offers neither a wholesome image of South Africa as a rainbow nation (the klopse are associated with the city���s coloured working class), nor does it represent a notion of ���traditional���Africa.

The klopse seems to diminish in the eyes of the city each year, and of late has a rival in the more hipster and corporate-friendly Cape Town Carnival in March every year (in which the “rainbow nation” is the central motif). Each year, after negotiations that are often laden with tension, the city lays on municipal services, such as security and traffic control, while the traditional carnival bodies march through the former neighborhood of District Six, and onto the main downtown strip of Wale Street.

The media conversation about this klopse carnival follows a familiar pattern. It gets caught up in, and perhaps even abets, the seasonal animosity between sections of the carnival community on one hand, and the city authorities on the other. Cape Town is indeed a city at odds with its cultural present and past. To make sense of this, it is worth thinking not just about Cape Town���s global present, but also its global past.

The city���s traditional carnival is a touchstone for several indicators of the past and present: its historic relationships to the Indian Ocean and Atlantic worlds, to its indigenous population and to the fact that its local economy was built on the import of slaves from elsewhere and of black immigration from other parts of the colonial imperial world of the 19th century���something it shares with Atlantic carnival cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Havana, and New Orleans. And like these settings, it is the slave economy that Cape Town has in common with these places. It is implicated in making race part of the lived social reality for people.

There are, in fact, several distinct carnivalesque scenes in Cape Town: including the klopse, the Community Carnival, the UCT and Stellenbosch student Rag, the black sport-aligned ���Mardi Gras��� of the 1970s, and the Mother City Queer Project to name a few. This array of carnivalesque networks itself tells a story of the racial divide. The ones that are marked traditional occur in a set with the klopse, Malay Choirs, and Christmas bands at their core, but will also include carnivalesque calendar events, such as Guy Fawkes, the peak of the social langarm (slow dance) dancing season. They are best understood in a dynamic relation between these forms, not isolated from each other as we tend to discuss them. But I will restrict myself to the klopse and its relation to the rest of the city. The klopse registers as a local phenomenon with only passing interest to international visitors or observers. Indeed, the 2020 klopse season is now in full swing. There will likely be pronouncements about the city���s jazz history, which will make vague references to its carnival tradition, but this relation is a troubled one. The carnival and modern Cape Town are radically out of step with each other.

Arguably, we need better tools to make sense of these issues, to escape the inarticulacy that klopse seems to trigger, the sense that it is abnormal and antiquarian, the impasse of identity politics to which it gives rise. Beyond a well-worn set of tropes about klopse���s roots in slave emancipation, colouredness, and tradition, we don���t seem to know how to talk about the klopse carnival���s sensory fabric, its capacity to excite, its traditions, its revelry in beauty and ugliness, its penchant for caricature. Klopse���with its associations with the hurtful manipulation of blackface in the Apartheid years���remains an unspeakable language. No newspaper or radio station is at hand to capture, beyond generalized and clich��d terms, the social investment in the competition, the excitement it generates in local neighborhoods, the drama about colors, songs, who will win this year, and so on. There is no shared material history or language to guide public discourse: the comic inflection in Cape Afrikaans, the ambiguities of cross-dressing and Cape ���jive talk.���

We might say that the klopse carnival has become part of the natural racial order. We have conflated carnivalesque traditions with markers of race so that the two are indistinguishable. In this scheme, for example, colouredness talks with a funny, inflected Afrikaans accent. These are stereotypes produced in a discourse that has now come to represent the natural state of colouredness. Part of the tragedy of carnival is that, through a complex process, Apartheid���s bureaucracy, planning, and pageantry successfully appropriated its tropes as markers of the coloured race. It is no accident that you will not find the fabric of carnival embroidered in the literary traditions of the country or the region. Very few poets or novelists have engaged with the comic sensibility of the Cape apart from the poet Adam Small, Rehana Rossouw���s writings or the work rapper CPT Youngsta. Yet, it reverberates in a new hip hop generation in much more serious tones.

Even though it is now understood as such, there really is nothing ���natural��� or inevitable about this condition. Carnival’s everyday practice transpires under the veil, inside local communities despite, if not because of, indifference from the rest of the city. Tourism events generally play with the picturesque, they haul out a small troupe to play folk forms such as the songs ���Welcome to Cape Town,��� or ���Daar Kom die Alibama������the latter a song about a mid-19th century confederate ship that visited at the Cape with blackface entertainers in tow���to add some quaint local flavor for tourism events.

When the big showcase happens in the city���s downtown streets, the shops and restaurants proximity to the march close or take precautionary measures to shield their customers. It seems to be regarded as an imposition rather than something to participate in or celebrate. The two economies���one traditional, archaic and quaint, the other global and sophisticated���seem to be essentially incompatible. Over and above the indifference from business and local media, almost none of the city’s artists, galleries, institutions, and very few of its musicians have any relation to what may arguably be the creative event with the most inclusive, and richest history in the city���one that is intertwined with Cape Town���s unique cultural value propositions in language, music and other spheres. This is not simply to blame, but to point out what has become so obvious as to be ���natural.��� Yet it in the language of the non-racial sports movement of yesteryear, carnival reminds us that we pursue normal activities in a still profoundly abnormal society.

March 6, 2020

When things fall apart

[image error]

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

When Alassane Ouattara, a former deputy managing director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), first became president of Cote d���Ivoire 2011, he promised that economic growth would reconcile Cote d���Ivoire and heal old wounds after nine years of civil war.

In reality the sparkling economic progress that has been made since 2010 has had little bearing on most citizens, with 46.3 percent of Ivoirians still living in poverty. Trickle-down economics has failed to alleviate the biting hunger that nearly half of Ivoirians still suffer, while it has also struggled to reunite them. Politics remains as divisive as ever and although Ouattara announced on March 5th that he would not seek an unconstitutional third term in elections in October, as he had threatened to do, his increasingly authoritarian tendencies remain a concern.

This is a far cry from 2011. Then, after months of bloodshed that resulted in the deaths of 3,000 people and the displacement of 300,000 others, Ouattara���s arrival in power was regarded in much of the world, and in many parts of Cote d���Ivoire, with relief. Because he was a technocrat, he was seen by western elites and international financial institutions as a figure who might be able to stabilize a country which had spent nearly nine years at war.

On paper and by the standards of the market, Cote d���Ivoire is doing well economically. In the decade since the war, his administration has demonstrated a capacity to rebuild a broken economy and to attract considerable foreign direct investment. Ouattara���s Cote d���Ivoire has a GDP that has grown consistently at over seven percent and it has repeatedly been named in the top three fastest growing economies in Africa. Vast infrastructure projects abound, with a metro due to be installed in Abidjan by 2023 and new cafes, restaurants, and hotels emerge almost daily.

Ivoirians complain that these strong economic indicators have not improved their daily lives and that while investment floods into Cote d���Ivoire almost half of all Ivoirians are hungry. Additionally, while these new finances might help development eventually, they do not resolve the grievances that sparked the nine-year on-off civil war.

Nonetheless, international financial institutions and western governments have dealt with Ouattara and his business-friendly policies with glee. The president has sought out efficiency and has made it much easier to do business in his country. In 2014 and 2015 the World Bank noted that Cote d���Ivoire was among the top ten most improved places to do business in the world.

Ouattara has also brought some political stability to the country. It is no longer dangerous to travel around Cote d���Ivoire and a cease-fire line that marked the frontier between the north and south has long since been removed. Residents, even those who oppose Ouattara, express contentment that they are no longer faced with a daily threat of violence, while police road blocks have significantly reduced. Extortion is largely a thing of the past.

The fa��ade slips away

But, as the years have gone on questions have increasingly been asked about the government���s respect for human rights and democracy. Additionally, political space has tightened and opposition leaders are concerned for their safety.

In 2016 President Ouattara held a referendum on reforms to the constitution in Cote d���Ivoire, which was successful but saw only 42 percent of the population participate. The government plowed ahead with reforms anyway, creating a Senate, which Ivoirians lamented was expensive, unnecessary and would simply allow the president to tailor the composition of the government to his requirements. A third of Senators���33 of the 99���in the Senate would be unilaterally appointed by the president.

This was only the beginning of a series of moves that undermined democracy in Cote d���Ivoire. Ouattara has increasingly cracked down on the opposition, choosing to arrest at will those who oppose him or seek to stand against him. The latest in a stream of such unsettling actions came in December 2019, when the president issued an arrest warrant for Guillaume Soro. The former head of the National Assembly and leader of the Forces Nouvelles rebellion, which ruled northern Cote d���Ivoire between 2002 and 2011, had been due to return to Cote d���Ivoire from a European tour when he was informed he would be arrested if he did so. He diverted to Ghana to avoid imprisonment.

The government claimed that Soro had been involved in a coup attempt and provided an audio recording to prove it. The tape however, allegedly dated from 2017, prompting Ivoirians to ask why the president had taken so long to use it against the ex-rebel. If he was guilty of such destabilization attempts while he was part of the government, why had the government waited so long to issue an arrest warrant?

Few can doubt that the impetus for such an action was the decision by Soro to announce, whilst in Spain in October, that he would stand as a candidate in the presidential election this year. The announcement likely disconcerted the government, which saw his northern and youth voter base as a potential challenge to its traditional strongholds in the north.

Not only did the government issue the arrest warrant for Soro but it also detained numerous supporters of the opposition candidate, including five members of parliament who are leaders of Soro���s Generations et Peuples Solidaires movement. Soro���s borther, Rigobert Soro, has not been seen since December 30th, 2019, which Amnesty International claims is the consequence of a forced disappearance.

Signs of hope?

Ouattara���s recent declaration that he would no longer seek to stand for an unconstitutional third term has allayed some fears of an autocratic turn in Cote d���Ivoire. However, the ongoing crackdown on the opposition and the failure to agree on a way forward regarding the composition of the electoral commission, which the opposition still regards as biased, cautions against viewing this decision as a resolution to Cote d���Ivoire���s political problems.

That Ouattara will not run in October���s election is undoubtedly a relief for Ivoirians who had feared the poll might be a re-run of 2010, in which Ouattara, Bedie, and Gbagbo faced off. But unless the president chooses to renege on many of his other undemocratic moves and opens up a genuine political dialogue with the opposition, reforms the electoral commission and releases political prisoners, tensions will remain high and the election could yet prove to be as controversial as the infamous 2010 poll.

March 5, 2020

Cameroon in conflict with itself

Cameroonian soldier. Image credit Sgt. Kyle Fisch via US Army Flickr CC.

Since the war in Southern Cameroon began, there has been a persistent narrative on social media that seeks to portray Southern Cameroonians as innocent victims caught in an unholy relationship with East Cameroon. This narrative becomes sharper every time there���s a massacre, like the recent one in Donga Mantung. However, Southern Cameroonians are not as innocent in this relationship as some appear to think. The elites of the region are especially complicit in creating this Cameroon which is now at war with itself.

Let me explain.

This crisis has been long in the making, but it has escalated into a war which is now being fought by the Cameroonian army and different secessionist groups scattered all over the anglophone Southern Cameroon. Partly due to the current war, a narrative has developed that paints francophone Cameroon as the main source of the catastrophe that is engulfing an otherwise innocent and victimized anglophone Cameroon; a narrative that clouds the fact that the current crisis has been created by government actions and does not reflect the attitude of francophones towards anglophones in the country. The innocence and victimization of anglophones in the country is also overstated. The Cameroon we have today, the Cameroon now in conflict with itself, is a Cameroon that was created by both English- and French-speaking Cameroonians.

The dominant narrative of the crisis is that since the reunification of British Southern Cameroon and French East Cameroon in 1961, the minority Southern Cameroonians have been systematically marginalized, with matters coming to a head in 2016 with the Biya regime���s brutal crackdown against those protesting the assimilation of Southern Cameroons��� educational and judiciary systems into French Cameroon���s system led to armed resistance. This narrative is only partly true. It is true, for example, that English is marginalized even though English and French are the official languages of the country. Official documents are required to be written in both English and French, yet official documents are often available only in French. When English versions are available, these are often poor translations of the French. English-speaking Cameroonians are expected to speak French in official circles while French-speaking Cameroonians are not expected to speak English. However, anglophones have also played active roles in the marginalization of many in both anglophone and francophone Cameroon.

For example, Southern Cameroonian elites played critical roles in consummating the union between anglophone and francophone Cameroon, especially through the process that led to the increasing assimilation of anglophones into the francophone system. As the historian of Southern Cameroons, Bongfen Chem-Langh����, has noted, the process of assimilating Southern Cameroonians into the francophone system, from the period of the reunification, was certainly enhanced by the actions of some politicians from Southern Cameroons, such as Solomon Tandeng Muna, who advocated for ���the creation of a single political party and a unitary system for the whole country.��� Muna���s slogan to achieve this goal was ���one country, one government, one flag, one currency.��� For holding this position, Ahmadou Ahidjo, the first president of the reunified Cameroon, appointed Muna, first as Prime Minister of Southern Cameroons (1968), and later, as Vice President of the Federal Republic (1970). Successive Southern Cameroonians have since been appointed to the post of Prime Minister of Cameroon, including Simon Achidi Achu, Peter Mafany Musonge, Ephraim Inoni, Philemon Yang, and the current Prime Minister, Joseph Dion Ngute. While it is true that southern Cameroonians have been in the minority in high profile state offices, those who have been appointed to these offices have often used them to line their own pockets and pass on benefits to cronies. They have hardly protested the mistreatment of Southern Cameroonians.

The narrative of a homogenous marginalization of anglophone Cameroon, which is used to justify the current war by those fighting for separation is, in reality, propaganda. This narrative is amplified especially when there is a massacre, such as the one that happened in February 2020 in the village of Ngarbuh, where government forces and some armed Fulani people are believed to have murdered pregnant women and infants. We need to radically change this narrative to acknowledge anglophone Cameroonian complicity in fueling this conflict, in order to try and bring about its end.

March 4, 2020

Democracy needs dissent

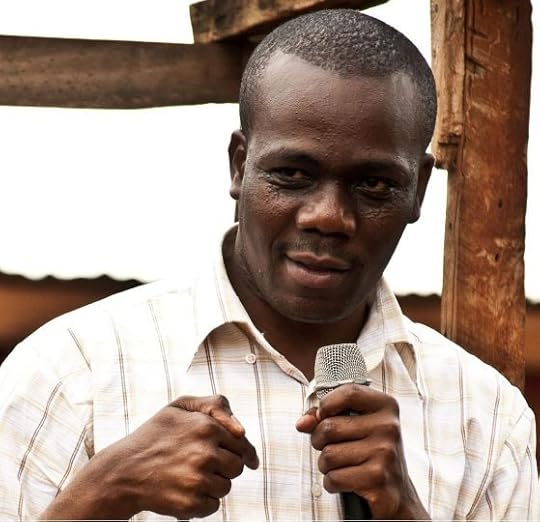

Zitto Kabwe. Image credit Pernille B��rendtsen via Flickr CC.

The credibility of opposition politicians in Tanzania has come under serious scrutiny lately, not least because of recurring defections to the ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM). Recently, Dr. Vincent Mashinji, the former secretary-general of the main opposition party, Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA), joined CCM. ���I had to evaluate how we argue day and night,��� he stressed, ���something that delays us in taking part to create development in the country.���

Zitto Kabwe, a leader of arguably the second main opposition party, ACT-Wazalendo, was as supportive of Mashinji and other defectors��� constitutional right to defect as he was critical of the impact on opposition politics. For him, such defections are disheartening as they discourage wananchi (the people) and shake their trust in opposition politicians. This, Zitto insists, is especially the case when it involves top leaders, MPs, and local councilors defecting to the ruling party. For me, as one of the wananchi whose trust in Tanzania���s politicians has eroded over the years, opposition politicians and their parties are indeed not perfect, but they are critically needed.

The case of Zitto himself is illustrative. In his formative years he was highly critical of the role of the World Bank in undermining African economies in general and the Tanzanian economy in particular. Trained as an economist at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM) and groomed to be an activist by feminists at the Tanzania Gender Networking Programme (TGNP), his promising political career started at CHADEMA where he rose to become deputy secretary-general. However, he was pushed out of this party in 2015, partly due to internal power struggles. He then co-founded ACT-Wazalendo, which has been rapidly growing, especially after a leading faction of the then second main opposition party, Civic United Front (CUF), joined ACT in 2019.

As an activist, in 2001 Zitto protested the visits to Tanzania of then World Bank President James Wolfensohn and then Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, Horst K��hler. As he told investigative journalist Erick Kabendera and others (for Celebrating 50 years of Development Partnership: The World Bank and Tanzania), about what happened during that protest:

They held their meeting here to discuss about the user fees the World Bank and IMF were pushing for Tanzania to charge on health, education, and privatization of water supply in Dar es Salaam city. I was part of the group of students who were against the idea and I carried a banner which literally said the user fees would only be affordable by [Wolfensohn and K��hler].

The TGNP and allied civic organizations led the protest. ���I was in police custody for eight hours before I was released,��� Zitto continued, ���but our main concern was that our economy was still not growing well so the majority of families were not able to pay for education of their children.��� (Incidentally, Kabendera had been in detention without trial from July 2019 to February 2020).

An account by Professor Marjorie Mbilinyi, then working at TGNP, captured more vividly what happened in real time:

The police used force to stop the demonstration. Three activists were arrested on the spot, including a staff member of ��� TGNP, Daudi Kweba and two leaders of the National Youth Forum (Gwandumi Mwakatobe and [Zitto] Kabwe), and bundled into police cars. A journalist from a major daily newspaper, Mtanzania, Jackton Manyerere, was severely beaten by police when he tried to pick up some of the fallen placards. The chairperson of TGNP, Demere Kitunga, was beaten at Central Police Station when she arrived to bail out the others, and later arrested, along with three other members of TGNP. A total of seven activists were held and interrogated for six hours, and only released at nightfall after the intervention of five top human rights lawyers.

It is telling that over the years, most civic and political activists have shifted their approach to the World Bank���s involvement in Tanzania, from staunch critiques and protests to pragmatic engagements and negotiations. The World Bank���s charm offensive, which includes, among other things, inviting activists to ���working dinners��� to pick their brains, seems to be working. As a leading financier of development, it is also increasingly seen as a relatively benevolent entity to entreat when things seem to go drastically wrong. For instance, the World Bank is given some credit for the decision of the Tanzanian government to amend again its Statistics Act of 2015 in 2019 following a controversial amendment of 2018 that made it illegal to, among other things, question official statistics and was affecting the World Bank���s work on statistics in Tanzania.

This background partly explains Zitto���s letter to the World Bank in January 2020. At the time, the Bank���s Board of Directors was considering a US$500 million loan for a Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project (SEQUIP) in Tanzania. SEQUIP���s goal is to ���support the expansion of effective Alternative Education Pathways if girls drop out or have to leave public school.��� An updated project information note states that SEQUIP will do so by ���supporting girls who become pregnant to access recognized, quality Alternative Education Pathways (AEPs) to obtain lower secondary certification and continue with upper secondary education or post-secondary education.���

John Magufuli, the President of the United Republic of Tanzania, had declared that during his tenure, pregnant girls are banned from attending public schools. Gender and human rights activists have been up in arms about Magufuli���s directive, with some also sending a letter to the World Bank. ���Awarding $500m at this time would be a slap in the face of girls and women who are treated in this way,��� Concerned Citizens of Tanzanian Civil Society stated in their letter, ���and will be taken as a full-throated endorsement of this violently misogynist regime.���

Zitto���s letter to the World Bank also emphasized ���worsening gender and human rights conditions.��� He then continued with, ���it appears that the Bank���s approval of the Productive Social Safety Net project in September only emboldened this government.��� Then after asserting that ���we fear that, absent checks and balances, this enormous investment will be used by the ruling party to distort our electoral process,��� Zitto pleaded with the World Bank:

I am asking that you suspend tending to this government until basic checks and balances are restored in Tanzania. These checks and balances include a free press, freedom of assembly, free and fair elections, and the reinstatement of the Comptroller and Auditor General.

Although Zitto���s letter did not specifically address the issue of pregnant students, it was generally interpreted as a protest against the government���s planned policies and in his tour to Britain and the United States in early 2020, he engaged with questions about it. For instance, he told CNN that ���the way the loan is been structured [means] the young girls who get pregnant for whatever reason will be put in separate school[s]��� and, after reiterating that this ���is not right,��� he mused: ���I am wondering how can the World Bank allow this.���

Both local and international media covered Zitto���s letter adequately and, in some cases, even sensationally, especially after a parliamentary debate in which he was labelled a mercenary and a traitor (among other insults). In this debate an MP for the ruling CCM, Abdallah Bulembo, uttered the words below that were widely interpreted as the issuing of a death threat to Zitto:

Mheshimiwa Spika, usaliti ��� mkiwa vitani pale Kagera, Tanzania inapigana na Uganda, akitoka mtu mmoja akapeleka habari zenu, hatakiwi kuvuka kurudi, anatakiwa auwawe kule kule. Usaliti, anachokifanya Bwana Zitto ni usaliti mkubwa katika nchi yetu. Sasa nafasi ya kuvumilia Mheshimiwa Spika mi si mwanasheria sijui taratibu za kibunge, anaposaliti mtu nchi, anatakiwa kurudi Bungeni humu? Hatakiwi, huyu ni msaliti. Na serikali mko pale wanasheria. Mheshimiwa Spika, wanasheria wako humu, hawa wasaliti wanaotoka Tanzania kwenda nje wakasaliti nchi yetu, mnapokeaje pasipoti zao kurudi nchini? Si warudie polisi pale ili tujenge heshima katika nchi? Mheshimiwa Spika, huyu Bwana kazoea, anatakiwa apate kiboko kizuri sana

(Honorable Speaker, betrayal ��� when you are in a war there in Kagera, Tanzania is fighting with Uganda, then one of you crosses over to the other side and send your information there, he/she is not supposed to cross back, he/she is supposed to be killed right there. Betrayal, what Mr. Zitto is doing is a great betrayal to out country. Now I don���t have the time to be patient, Honorable Speaker, I am not a lawyer, so I don���t know the parliamentary procedures; when a person betrays a country, is he/she supposed to come back to the parliament here? He/She is not needed; he/she is a betrayer. And the government, your lawyers are there. Honorable Speaker, lawyers are here, these betrayers from Tanzania who go out there to betray our countries, how do you receive/accept their passports to return to the country? Why don���t they come back to/through the police office there so we can build/maintain the respect of this country? Honorable Speaker, this Mister is so used to doing this, he is supposed to receive a very good cane/caning.)

Inside Tanzania, The Citizen newspaper, once banned by the government, ran cautious, if professional coverage. Online, Tanzanians were polarized with many activists siding with Zitto while diehard supporters of the ruling party vilified him. Those of us who view the World Bank as a leviathan that is capable of devouring while nourishing were caught in the middle, though we sympathized, if not empathized with Zitto. One���s life, after all, is sacrosanct.

When we reminded Zitto that he once chided another fiery opposition MP, Tundu Lissu, for asking the international community to suspend aid to Tanzania, Zitto, to his credit, confessed that he had made a mistake. ���It was wrong,��� he affirmed. ���I apologize for that.���

Ironically, some opposition activists seek external pressure on the government from some of the same entities that have emboldened many autocratic regimes in Africa and elsewhere. That is why one of the criticisms that has been leveled against the likes of Zitto and Lissu is for seeking assistance from mabeberu (imperialists)���a term popularized during the heydays of Ujamaa (Mwalimu Julius Nyerere���s African socialism), and increasingly used sarcastically by critics of the current regime and the ruling party. This criticism is mainly invoked against those who seem not to be wazalendo (nationalistic or patriotic) enough. Yet, Zitto has been adamant on embarking on what he calls ���a program of dialogue with the international community to ensure that the necessary pressure is placed on the Magufuli regime to ensure free and fair elections in 2020.��� In fact, Zitto���s letter ends with a request to meet with members of the World Bank���s Board of Directors in Washington DC ���to explore a more positive role for the World Bank to play in the development of our country.���

We may love or hate them. Either way, opposition parties are needed in Tanzania. Our multiparty democracy can hardly thrive without maverick opposition politicians, who ensure that the ruling party and the government of the day are always on their toes, lest we degenerate to full-blown authoritarianism.

March 3, 2020

Afro football fever

Ugandan soldiers serving with the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) play football with young Somali boys in the central Somali town of Buur-Hakba. Image credit Stuart Price via AMISOM Flickr CC.

It can be hard to see how the real energies and possibilities of African football survive in the niches left by globalization. Sometimes one needs a sharper eye. Both visitors and the leading lights amongst a new generation of African photographers have that. Taking football as their subject matter, they have helped capture the game���s deep historical meanings and living everyday presence. The Senegalese, Omar Victor Diop, dressed as little-known but important figures from the African diaspora, took a series of self-portraits based on paintings from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Styled and posed like the African studio photography of the twentieth century, Diop made the twenty-first century connection to these images by adding an object. Pedro Camejo, the only black officer in the army of Simon Bol��var, wearing goalkeeping gloves. Badin, first a slave, then butler and diarist to Princess Sophia of Sweden, holding a red card. The Belgian artist Jessica Hilltout offered no ironies or self-conscious intertextuality in Amen: Grassroots Football, a photo journal of a seven-month trip across rural and small-town Africa from Togo, Mali, and Ghana to Mozambique, Lesotho, and South Africa. If the many photographs of players, feet, home-made sandals and torn sneakers veer towards the gratingly pitiful, her photographs of their hand-made balls are quietly breath-taking. Constructed from twine, condoms, rags, and tape (and each exchanged for a factory-made ball), in Hilltout���s photographs they come to seem like finely cut jewels, testament to the exquisite ingenuity, craft, and resourcefulness of Africa���s poor. The sharply dressed African women in portraits by Nigeria���s Uche James-Iroha seem confident on the ball, and set against tattered football nets, put a face to the rising tide of women���s football in Africa. More straightforward but emotionally richer is Andrew Esiebo���s brilliant series Grannys, double portraits of African women as football players and as grandmothers with their grandchildren. His collection of street football, For the Love of It, shot in South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana, is the most exceptional of all, capturing in a blaze of chromatic brilliance the harsh environments and momentary joys of the game: teenagers playing three-a-side on a patch of concrete cleared of broken glass beneath the vast raised motorways of Lagos; a cross-legged game of disabled football on the hot tarmac of an Accra taxi rank.

Steered by such imagery one can see that that life is emerging in women���s football in Africa, taking off with what looks like the same kind of energies that fired the men���s game when it first arrived. Africa has acquired its first professional women���s leagues in Nigeria and Burundi, and when Isha Johansen was elected to head the Sierra Leonean Football Federation in 2013, she became its first woman football president. Africa has also acquired its first openly gay male footballer when, in 2016, the second-division South African goalkeeper Phuti Lekoloane came out. This was an act of uncommon bravery on a continent where football has become the site for some of the homophobic moral panics, nurtured by the Evangelical churches and opportunist politicians, that have occupied the African media. In 2009, Uganda���s FA went as far as to systemically outlaw sodomy in its statutes and conduct a witch hunt amongst coaches. In 2013 the Zambian authorities tried to do the same, though both were thwarted by FIFA���s insistence that such statutes were not in accordance with their own. Nonetheless, a vice-president of the Nigerian football federation���a man hitherto silent on widespread accusations of heterosexual abuse in Nigerian football���thought “Lesbianism kills teams. The coaches take advantage.” In South Africa, teams kill lesbians. In 2008, Eudy Simelane, a high-profile out player with the women���s national team, was gang-raped, stabbed twenty-five times, and left for dead in an act of calculated “corrective rape.” Yet the seeds of something else are stirring when, in Botswana, the football association starts supporting five-a-side tournaments for the nascent LGBT rights community.

Life is also stirring in Africa���s private and civic sectors. It remains the case that the vast majority of clubs in the continent (outside of South Africa) are controlled or funded by state organizations: armies and police forces, city and regional governments, ministries of state and national oil and mining companies. None of this is good for football governance. In the case of Nigeria���s state governments, it is simply disastrous. In this context, the transformation of football clubs into conventional businesses has introduced a degree of transparency, shared decision-making, and financial responsibility absent hitherto. It has also created a constituency in football with a direct interest in anti-corruption programs. This kind of change has been most invigorating in Kenya, where real advances can be seen in the quality of local football and its governance, but the same process can also be seen at work in South Africa, Tanzania, and even in Nigeria.

One African side has actually made it to a World Cup final: Angola���s amputee football team, runners-up to the Russians in 2014. Their victory was the product of the devastating and widespread use of landmines in the country���s brutal civil war. The same tragic conditions have made Liberia African champions. A transformative sport for the disabled, and the often traumatized and excluded veterans, amputee football has acquired huge public support. The opening match of the 2007 African Cup in Sierra Leone between the hosts and Ghana drew 10,000 people. The same hunger for alternatives to poor-quality professional football can be seen in Senegal, where the neighborhood-based amateur nav��tanes championships draw bigger crowds and stir infinitely more passions than the moribund official league. In Lagos, young professionals dissatisfied with both the grim conditions of local football and the passive consumerism of the Premier League have started their own amateur tournaments, the Twitter Premier League and Socialiga, as new kinds of social events for urban middle-class youth.

For the hundreds of millions warehoused in the shacks and self-builds of Africa���s slums, there is, before anything else, the problem of where to play. In the absence of public investment, the only options are the rare open spaces in these superdense neighborhoods and, given the complete absence of municipal refuse services, these are invariably piled high with rubbish and food waste. MYSA, the Mathare Youth Sports Association, was born of this dilemma in one of the largest slums in Nairobi. It now runs football coaching, leagues, and boot libraries for 25,000 youths in Kenya, 5,000 of them young women. Teams score three points for a win, one for a draw, but six for doing their part in a now highly organized clean-up operation (and at least seven members of the squad need to show up). MYSA is also run by the youth of Mathare in a long-standing democratic framework, which has created a pipeline of educated, confident social entrepreneurs and local leaders, and made MYSA the backbone of civil society in the city and a key provider of health and education services. It has also won the World Street Football championships twice. MYSA, though, is just one of a vast archipelago of NGOs that have emerged all across Africa, tapping into the game���s extraordinary social potential. Alive and Kicking were Africa���s first manufacturers of footballs. Based in Kenya, they crafted super-durable, low-cost leather balls designed to survive on the rough terrains of the continent, selling half and donating half of their output. The Tanzanian club Albino United provided a safe space and an educational tool for football players with the eponymous condition���one which carries a deep and pervasive taboo in much of Africa.