Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 204

September 14, 2019

Beyonc�� and the Heart of Darkness

Disney Studios promo image, credit Kwaku Alston.

John Kani, the South African actor who voiced Rafiki in the 2019 remake of Disney’s��The Lion King, said in an interview��regarding the film that a black South African audience would ���take the story as an African story��� when they see The Lion King, they���ll see the parallels.��� So does this mean we are to assume that this story���of a young lion whose destiny is stolen by his wicked uncle and his journey to reclaim it���would capture Africans��� existential struggle of living in a state of development, stunted by European colonialism and its continuous manifestations? Perhaps this allegory is not so obvious in the narrative of The Lion King, but if we zoom out to the one surrounding the film, things start to become a bit clearer.

In the global marketplace for culture, from the colonial-era on through today, Africa has been a perennial source for exotic cultural products and opportunities for self-aggrandizement. As Chinua Achebe once asked in regards to Joseph Conrad’s English language classic novel��Heart of Darkness: ���can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind?��� In contrast to Conrad’s time, however, black people both on the continent and in its diaspora are now imagined as part of the audience. They are also involved in the production. In the 2019 remake of The Lion King, there is a diverse black cast including big names such as Chiwetel Ejiofor, Beyonc�� Knowles-Carter, and Donald Glover. However, Disney���s hegemony in the film industry, and the��profit oriented��impetus behind the production, cast doubt as to whether this is really an exercise of continental empowerment.

That’s not to say certain “gifts” weren’t offered up for African audiences. Beyonc�����s thematic album,��The Gift, inspired by the film, her ���love letter to Africa,��� accompanied the movie���s release. It was here she was able to dabble in the latest Afropop sounds and collaborate with some of the continent’s largest stars. Her invocation of African mythology was also heralded. She sang in the number “Mood4Eva” that she was the sister of Naruba,��she was O���un.��Acclaim rang out for her using the Yor��b�� language,��privileged amongst Nigerian fans over the other languages used on the album. However, the tilt of many of these praises, some even running close to orgiastic revelry, begged the question of the intrinsic value of Yor��b�� beyond just a sign post for self-representation.

Even critiques of the film fall short in this regard. Nancy Adimora in gal-dem zine writes:

I would understand if the movie in question was about how Ishmael from Sierra Leone, and Ashira from Mozambique, met and fell in love on Facebook, got married and decided to move to Rwanda, where they met a mysterious traveller who explained to them why Ghanaian jollof never bangs, so they decided to travel across the entire continent, searching for the perfect jollof recipe, only to discover that it was in Nigeria the whole time.

In other words, to earn the right to claim Africanness, a thing must exhibit the traits of all the kinds of Africa that exist and the Africans who exist in them. Where this and similar critiques of Africa’s representation fail is in their presupposition that a composite story of Africa or African lives is possible. Secondly, it reveals a failure to understand that a person can only represent what they see and what they see is often dependent on their position relative to the observed; which is to say, the ability to observe and represent a thing is a question of power. It has long been observed that power relations distort European representations of Africa, but it is also the case that such distortions appear in the intellectual works of the contemporary black diaspora.

The ease with which African-American and other diaspora intellectuals situate themselves in the center of histories of global black experience is akin to the ease with which western intellectuals have traced philosophical thought in an unbroken line from Socrates to Hegel. Brent Hayes Edwards writes in Social Text���s ���Black Radicalism,��� that ���an important feature of the common ground of black radicalism is that it is consistently diasporic.��� The suggestion here is clear and damning: Blackness achieves cultural and political dynamism only when it has left Africa, when it is in contact with the Euro-American character. If there is anything most striking about this, it is how perfectly it mirrors the colonial disposition toward Africa. It is important to note the ways in which members of the African diaspora participate in colonial archives and exemplify the assumptions of the metropoles from which they observe the world.��Yet, so few black thinkers in America seem able to grapple with the implications of their Americocentrism in relation to Africa.

Once we see beyond the prism of pan-Africanism to the power imbalances within Africa-diaspora relations, what ramifications might this have on future exchanges? To start, we could no longer consider it innocuous that the most popular Hollywood depictions of Africa among Black American audiences���Coming to America, Black Panther and The Lion King���all follow themes of royalty. The Africans in Coming to America and Black Panther are cast as if from a past of unimpeachable glory and might; the Africa of pyramids and Kente cloth inlaid with gold. It is easy to understand why Black Americans identify with these stories. They derive power from a particularly Afrocentric essentialism, which uses and exaggerates certain elements of pre-colonial Africa as an oppositional tactic to western narrative of Blackness as primitive and unaccomplished. But Achebe was well-aware of the pitfalls of this tendency:

I do not see that it is necessary for any people to prove to another that they build cathedrals or pyramids before they can be entitled to peace and safety. Flowing from that, I do not believe that black people should invent a great fictitious past in order to justify their human existence and dignity today.

Would a Zamunda without its prosperity or a Wakanda without the technological advancements of vibranium be of much interest to African-American audiences? It would seem that none of the Africas the rest of the world imagines are any of the ones Africans live and think and work and love and die in.

To understand foreign recognition of African excellence as an attempt to take ���Africa to the world��� is to internalize hegemonic knowledge of Africa and a social order in which the African is always peripheral to the central events and concerns of humanity. It helps to remember that ideology, as Stuart Hall writes, functions by nature on the level of the subconscious, and western hegemony still largely acts as the filter for taste and value. Even Achebe permits that ���Conrad did not originate the image of Africa which we find in his book. It was and is the dominant image of Africa in the western imagination and Conrad merely brought the peculiar gifts of his own mind to bear on it.��� So when Beyonc�� writes as part of her love letter to Africa a song entitled “Spirit” and dons Ow�� Ey���, one wonders if she has not also fallen into the same exoticist pitfall that Picasso and his friends fell into with “African” masks.

The exotic dress and dance, the vast deserts and mountainous landscape, and other such features in Beyonc��’s work present an Africa primed for a tourist’s escapade. Yet we Africans consume these representations and take ownership of them even though it could be argued that continental Africans are never the intended audience. If we were to accept that African-American cultural production suffers from the same failures of imagination as African-American knowledge production, we would see The Gift and our responses to it not as a singular case but indicative of pervasive complexes. We would pay closer attention to what we mean when we say that Afrobeats has become ���global,��� and what we mean when we argue over what region of Africa should have been represented above the other in American cultural products. We would see a recurrent reliance on essentialist tropes. We would have to admit that in our consumption of African-American culture is a sinister aspirationism, a desire to see blackness reflected back to us without the handicap of Africa. Beyonc�����s ���love letter to Africa��� is especially pernicious because it presents an Africa which can be transmitted through the peculiarities of a popular musical genre we all own and love. However, Beyonc��’s position as a popular American artist gives this presentation a political currency none of her African collaborators (or fans) have.

The authority of seeing and declaring the value that Africa has is a privilege that those outside the continent still claim for themselves, contested always from a position of weakness. We sense in Africanness an incompatibility with what is ���modern��� or ���contemporary,��� and despite belonging to the second largest continent, the African must earn her way into the global. There remains something irredeemably parochial about Africanness, something too insular to have wider relevance or application.

Achebe writes that he would have completed his critique of Conrad writing about ���the world of good it would do if the West stopped conceptualizing Africa through a haze of distortions and cheap mystifications but quite simply as a continent of people���not angels, but not rudimentary souls either���just people.�����His plan, however, is withdrawn when, he notes:

I thought more about the stereotype image��� about the willful tenacity with which the West holds it to its heart; when I thought of the West’s television and cinema and newspapers, about books read in its schools and out of school, of churches preaching to empty pews about the need to send help to the heathen in Africa, I realized that no easy optimism was possible.

Achebe had come to the conclusion that mere representation fails as a liberatory politic.

The work of reinstating African dignity, of ���setting the record straight��� was not one Achebe stumbled into by chance. No, Achebe reminds us that it is necessary to have an agenda, because those for whom Africa remains ripe for plunder are unremitting in their pursuit. We cannot be lulled so easily into assuming noble intentions or casual naivet�� on the part of any who declares interest in Africa or Africans. We must nurture a calculated cynicism to keep us aware that, as Achebe says, the ���extraordinary failure to comprehend [that black people want to be treated like people] has to be something more than inability. It has to be a refusal, an act of will, a political strategy, a conspiracy.��� And so, there are vested interests against which we must defend, and it is necessary to know to whom those interests belong, whatever forms they may take, even in ���the gifts of a Conrad,��� in pop culture sensations, in the guise of economic, political, or cultural self-empowerment.

September 13, 2019

Chester Williams and the making of modern South African rugby

Rugby World Cup in New Zealand. South Africa vs. Fiji kick-off. Image credit Stewart Baird via Flickr (CC).

It was at the Oppikoppi Music Festival in 1997 and Koos Kombuis was finishing up his set with a cover of Bob Marley���s ���No Woman, No Cry.��� He was basically riffing, adding a few lines for a proudly South African audience.

���No Woman, No Cry. No boerewors, no braai.���

And then:

���No Woman, No Cry. No Chester, No Try.���

The wordplay was nonsense in the context of the song, but it was fun nonsense, and the crowd ate it up.

The reference, of course, was to Chester Williams, the fine Springbok wing who had become in many ways the symbol of the aspirations of the ���New South Africa,��� the face of a South African national rugby team that, while still virtually all-white, in a sport that nationwide was still overwhelmingly white and fraught with racism, aspired to something different. In the lead-up to the 1995 World Cup in South Africa, Williams had become the face of the national side, an iconography that held up even when his hamstring didn���t, keeping him out of much of the competition, including the epic finals against New Zealand���s All Blacks, a dramatic, albeit try-free affair that saw the Springboks win in extra time to take the World Cup and seal their places as the symbolic embodiment of the Rainbow Nation of God.

Chester Williams died on September 6th. He was shockingly young, just 49 years old, and likely succumbed to a heart attack.

More than a mascot

And yet Chester Williams was more than just the smiling face that the South African rugby hierarchy could cynically slap on the side of buses and planes and billboards, though smile he did. Nelson Mandela recognized the importance of Williams to the 1995 team and Williams was happy to play along, swept up as so many millions of South Africans were in a feel-good narrative at a time when South Africa was very much about feel-good narratives.

First off, Williams was a hell of a rugby player. He was not a prototypical wing, but there was an element to his style that was reminiscent of what was long said of Muhammad Ali���he was bigger than those who were faster than he was, and he was faster than those who were bigger. He ended his career with 14 tries in Springbok test matches, a number that may not seem like a lot from the vantage point of the professional era (where elite players play at minimum three or four times as many test matches per year), but that put him near the top of the All-Time Springbok try scoring list when he retired in 2000 (he made his Springbok debut in 1993). Williams served as one of the bridges between the amateur and professional eras (the latter kicked in after the 1995 World Cup), from an era when international competition was still somewhat rare to one when it was ubiquitous. Prior to 1995 it would have been nearly unimaginable for a Springbok to earn 100 caps for his country (Williams earned 27; No Springbok who made his test debut in the green and gold before 1993 earned as many as 40 caps). Williams was a truly great player whose greatness cannot be captured in pure numbers given the rapidly changing nature of world-class rugby in the last quarter century. But in the years since his retirement, Williams has come to be seen as little more than a smiling face, a mascot for the 1995 team.��Yet, Williams was so much more complicated than that.

Race, Chester, and the Boks

Despite the Rainbow Nation gauziness that surrounds the 1995 Boks and perhaps especially Williams, there is an important and complex story beyond the feel-good narrative. For one thing, Williams was only the third black Springbok. The first was Errol Tobias, the halfback and center who first played against Ireland in May 1981 and was picked for the infamous 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand. His pioneering experience caught him grief from all sides���from whites who never believed he belonged in the Springbok side to begin with, and among anti-apartheid sports activists who saw him as an Uncle Tom.

The second black Springbok was Avril Williams who, like Tobias, was a star from South Africa���s flourishing Western Cape coloured rugby tradition. While invisible to the white South African rugby power structure, it gave the lie to the hoary old tale that ���blacks aren���t rugby people,��� an idea that many white South Africans continue to peddle in one way or another. Avril Williams earned two caps, both against England in 1984. His nephew, Chester, would be the third black Springbok when he debuted in 1993.

One of the issues facing these earliest black Springboks was the division within black rugby in South Africa. Tobias and Williams came from the South African Rugby Federation, a coloured rugby organization that while hardly pro-apartheid was willing to work within the apartheid structures to develop rugby within the coloured community. They faced resistance and criticism from the South African Rugby Union (SARU), a charter member of the South African Council on Sport (SACOS), which ardently opposed apartheid sport and those who accommodated its racist structures. SARU included SARF among the collaborators with apartheid. Thus when Tobias debuted for the Springboks, far from being celebrated across black rugby circles, he was met with excoriation amongst many who saw him as a sellout.

In Mark Keohane���s 2002 authorized biography of Williams, Chester: A Biography of Courage, Williams admits that he was ���a black player who knew very little about the history of the game among the black rugby-playing populations.��� He knew ���the basic things���that there were a variety of different unions, that not everyone played under the same banner, and that there was as much division within black rugby as there was between black and white rugby. It is a fact of our rugby history and we can���t shy away from it.���

Not only did Williams make sure to educate himself about this history, he soon received a primer through his lived experience.

Rainbow Nation idealism aside, race was always so omnipresent around Williams��� career that it was not subtext���it was text. He was the third Black Springbok, yes, but he was the first of the post-apartheid era, the first since the Springboks had been welcomed back into the world rugby fold in 1992. That process itself was, in the minds of most politically aware observers, seriously flawed. The Boks return was absurdly premature, as racism in the sport���s structures and throughout South African stadiums ran rampant. Nonetheless, Nelson Mandela shrewdly, if perhaps naively, saw sport, and especially rugby, as a tool of nation building and thus of transformation. Thus, Williams��� emergence was a godsend for Mandela, for white South Africa���s rugby barons, and for those who wanted the sort of easy victories that Amilcar Cabral warned us about.

Williams was not really into easy victories. He was well aware of the racial dynamics when he played, and in fact while he proudly identified as coloured, he was not comfortable as the ���black��� face of Springbok rugby. Despite being portrayed in Clint Eastwood’s��Invictus��as the heroic face of the Boks��(by two-cap Springbok and Williams contemporary McNeil Hendricks, who scored a try against Wales in 1998) for joyous township denizens, the reality was more complicated. In the Xhosa-speaking townships that the Boks did visit, Williams was not necessarily the hero. One of their many virtues is that children don���t always see race like adults do, and Mark Andrews, the giant lock of the mid-1990s Springboks, could speak Xhosa. That, along with his size and his avuncular nature, meant that many of the children were drawn to Andrews more than to the far more reserved Williams.

Furthermore, for all of the romanticized depictions of the 1995 team, things were not always as smooth as depicted. In Chester, Williams alleges racism within the 1995 squad and indicates a level of resentment about being used basically as window dressing for larger political purposes. Among those he would accuse of racism were popular fellow wing, but undoubted bad-boy, James Small who died of a heart attack in a strip club in July. Since the biography���s appearance Williams has modified his accusations multiple times���asserting that he did not face racism within the Springbok ranks but rather during the domestic Currie Cup competition; at other times he has denied them entirely, implying that Keohane (long known in South African journalism, and especially rugby circles, for his politically aware commentary and propensity to push the envelope to get a story) believed that Williams��� tale needed a boost. In the end, he simply refused to talk about the allegations against Small. Yet race, and especially racism in South African rugby circles is a pervasive theme in Chester.��And so, even if the allegations against Small are overstated, there are plenty of other stories to validate that Williams faced an uphill climb for acceptance throughout his career.

Beyond the sideshow of these nearly two-decade-long accusations, it is quite clear that Williams both faced and interpreted racism throughout his career and beyond. It would have been shocking had he not. For despite the smooth and clean Rainbow Nation narrative, South African rugby, like the country within which it operates, is not one of smooth, clean narratives. Williams went on to become a coach, seeing some successes and some failures as is characteristic of that unforgiving profession. With the passage of time Williams was able to dine on the glories of 1995, as has any Springbok who walks into a pub or caf�� in any city, town, or dorpie in South Africa.

Williams��� death has revived these Rainbow Nation narratives. Satellite channel SuperSport, which dominates sports broadcasting in South Africa, along with the rest of South Africa���s media landscape, sporting and beyond (and Williams has long transcended sport precisely because of these narratives), has and will continue to play up narratives of reconciliation and flag waving. And that is part of the story. But it is not the only part of the story, or even the most important part. Williams was a complex figure in complex times. He deserves to be remembered as such.

Postscript: The tragedy of the class of 1995

A sad footnote to all of this is the air of tragedy that increasingly seems to linger over the 1995 Springboks, the vast majority of whom are in their late 40s and 50s���still the prime of life. Williams death at 49 is not a singular tragedy, rather it is just the latest to hit that legendary group. Kitch Christie, the 1995 coach, passed away in 1998. He was only 58. Flank Ruben Kruger succumbed after a long fight against brain cancer in 2010. He was 39. Joost van der Westhuizen, one of the most beloved of all Springboks despite the occasional run-in with the tabloids, passed away after a courageous public struggle with ALS in 2017. He was 45. And James Small was 50 when he died in July.

As Williams acknowledges in Chester, ���Winning the World Cup in 1995 may have unified the nation for a week. It did not change my standing within South African rugby. I was a black rugby player and that somehow separated me from the squad.��� A few years later, in discussing his own ambitions at the beginning of his coaching career (and some of the fallout from the more explosive assertions he made in Chester),��Williams asserted, ���I’ve made no secret of the fact I want to coach the Springboks one day… What I hope, if that happens, is that nobody even notices how many black players are in my team. That would be the most important day in South African rugby.”

South African rugby has not yet achieved that goal. But when Siya Kolisi, the first black Springbok captain, leads his charges onto the pitch against the All Blacks in Yokohama City on the 21st of September the Springboks will be closer than ever. That is not enough, but Chester Williams is one of the figures who deserves credit for them being as close as they are, and that���s not nothing.

September 12, 2019

It is essential that governments think in terms of nation, not elites

[image error]

Mia Couto at Fronteiras do Pensamento, S��o Paulo 2014. Image credit Greg Salibian via Wikimedia Commons (CC).

My second encounter with the Mozambican writer Mia Couto is touched with a certain familiarity. We recognize one another right away, perhaps because being Mozambican is a code we share. I interviewed him for the first time in 2016, when he came to Barcelona to give a lecture at the Center for Contemporary Culture (CCCB) on the occasion of the exhibit, Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design. Strangely enough, we have never met in Maputo. Couto has become the pride of Mozambique, very respected within the country and beyond. His literature has managed to cross the borders of the Portuguese-speaking world. His books, translated into several languages���many a translator knows it���s not easy to put his words into their language���have brought him back to Barcelona. He was chosen to be the 2019 speaker for a much-loved festival in town, which he didn���t know existed: Sant Jordi Day, an annual cultural event that celebrates literature and encourages reading. Booksellers fill the streets of the city every April 23rd with stalls and books at discount prices. In any case, being African and Mozambican, I can���t say how pleased I am that he was chosen to be the town orator at the most important literary festival in Catalonia.

A writer and biologist by profession, Mia Couto has been publishing features, stories, and novels since 1983. Back then, Mozambique was deep in the throes of civil war, a tragic destiny for those who, like him, took part in the revolution and in the struggles for liberation from colonial power. His revolutionary and dissident nature hasn���t abandoned him, but he doesn���t need to raise his fist anymore because he knows how to seduce and dissent by murmuring. His view is that great transformations are not achieved by shouting, and this is why he is one of the few outside the government in Mozambique with a voice.

Wars are thorns that pierced our young country, and his books highlight this sharpest of thorns. His characters are borne out of the pain and suffering of a hurt and resilient country, because one thing that distinguishes Mozambicans is their resilience. When I read Mia Couto, I am transported to that red earth that saw me come to life, I can smell the Mozambican breeze, and I feel the fear of the unknown coursing through my entire being. Mia connects unconnectable worlds like few know how, perhaps because the strangeness of the human condition is what comes naturally to him. He recently published his Mozambican trilogy Sands of the Emperor (2015-2017), a historical novel in three volumes: Woman of the Ashes (first of the trilogy and only volume published in English to date, by Picador in 2018), The Sword and the Spear, and The Drinker of Horizons. The trilogy is historical fiction that narrates the war waged by Portuguese colonists at the end of the 19th century against Ngungunyane, the Emperor of the Kingdom of Gaza.

It isn���t an easy job trying to find some time with him, I have to call here and there, but he finally grants me a privileged time: Sunday afternoon. I meet with him at his hotel in hopes of having a conversation about his literature. However, Mia Couto is not only a writer or a biologist; he is also one of the most lucid contemporary African thinkers of our time. Ahead of him are two days of interviews and commitments before returning to his base camp in Lisbon, where he has settled for a couple of months in order to travel from there to Brazil, Barcelona, Switzerland, the UK.

Tania Adam

I���d like to start by talking about your Mozambican trilogy Sands of the Emperor, which was published last year in Spanish in one volume under the title of Trilog��a de Mozambique. I was surprised that you chose to focus it on the figure of Emperor Ngungunyane. For me and for an entire generation, the first thing that comes to mind whenever this emperor is mentioned is the song ���Ngungunyane na baliza������ We used to sing it when playing hide-and-seek. I don���t know whether kids still play the game, but we had no idea who he was.

Mia Cuoto

Yes, I think they still do play the game, but I doubt they know who Ngungunyane was, even today.

Tania Adam

This makes me think that, as Mozambicans, we don���t know our history well enough. What should we do to recover our historical memory?

Mia Cuoto

To begin with we should be talking about historical memories, in the plural, because there are different memories, and my intention with this book is to show that there are different visions of the past; there���s the colonizer���s view and there���s the view of those who were colonized. What I try to portray throughout the trilogy is that the colonizers and the colonized have different perspectives. The case of Ngungunyane is peculiar; he was an African that confronted colonial rule while he himself was a colonizer. He colonized half of Mozambique to the Save River and established a relationship of domination and oppression over other groups. This ambiguous position doesn���t fit into the simplified version we are told about Africa. That���s what got me interested in narrating this story.

Tania Adam

I suppose it���s the story of power and the people: a few colonizing the rest.

Mia Cuoto

That���s right. It���s also the story of human relations; there are people who may want to colonize others. Colonial history is a reflection of authoritarian human relations, the imposition of power, the invalidation of the other, the oblivion… But with this book I���ve tried to convey that memory is ours. Now is our time to tell our own stories. So far it���s been the European colonizer who has related history.

Tania Adam

Last November I was in Maputo for a short visit. I tried to get involved in cultural life, checking out what the city had to offer, going to bookshops, events and so on. I understood that the shortage of bookshops is a symptom of cultural poverty. Do you share this view?

Mia Cuoto

Impoverishment is obvious in Maputo but I just got back from Brazil and Portugal and I have to say that, sadly enough, this is part of a global poverty. In Brazil many bookstores are closing down. The trend now is for sales of what is commercially reliable; bestsellers or self-help books. It might not be as evident in the western world as it is in Maputo, which never had more than three or four bookstores, or if there were any at all it was during colonial times, serving only the small Portuguese elite.

But small groups of activists and organizations are emerging that produce books and make them known. It���s important for this production to include historical memories, because we are victims of a history that says that Mozambique began on Independence Day, on June 25, 1975. This single version of history, created and disseminated by the government, has been mistaken for that of the Mozambican nation itself. This occurs because we don���t have a good archive, a memory record where you can research information and understand the present.

For instance, if we had recorded the memory of the inhabitants of Beira, the area most affected by Cyclone Idai, we would have known that there were two cyclones in 1962 and 1963, and Idai wouldn���t have caught us by surprise. We could have gone in search of the knowledge gathered by the people who experienced it at that time, before independence. Yes, an independent and sovereign country began in 1975, but it already existed as a nation long before that.

Tania Adam

Is the erasure of this collective memory voluntary?

Mia Cuoto

I don���t think it���s intentional; it���s more a genuine issue of that period. We thought the time previous to independence was a time that belonged to others. From 1975 on, we were at a new turning point that was colonized by the winning party, FRELIMO (Mozambique Liberation Front). But now we are beginning to understand that Mozambique is more diverse and complex than anyone could have thought at the start.

Tania Adam

Who thought so at the start?

Mia Cuoto

In those days we took a stand, intellectuals, academics, scientists or me as a journalist, based on the thought that we were simpler. We were contaminated by the cause, drunk on the epic idea of building a new country. The idea of homeland and nation was vibrant. In that sense, I took part along with others in the extermination of Mozambique���s indigenous languages. We thought they should only be spoken in domestic spaces, not in the public sphere. During Samora Machel���s government (1975-1986) these languages were even forbidden at schools. Today I see this as sacrilege.

Tania Adam

So colonial values were perpetuated.

Mia Cuoto

It was not intentional nor was there any evil design, but there was a fear that accepting the different languages might create a division. At that time, the understanding was that there shouldn���t be any talk of languages or races. The outcome was that languages ceased to exist, as did whites and blacks and Indians and mixed race people��� Speaking about this was seen as a provocation. There was only Mozambicans; that was the narrative then. We had to build a new country.

Tania Adam

This reminds me of the pact of silence that the writer NoViolet Bulowayo talks about with regard to many uncomfortable situations in Zimbabwe, our neighbors. Did the same happen in Mozambique?

Mia Cuoto

Silence is the right term to describe what happened. When a new country is born, there is always the probability of silence, so I don���t think it���s a unique situation to Zimbabwe or Mozambique. If we look closely at the history of any nation, we���ll see that they are created through many instances of oblivion, because forgetting is necessary. Remembering is necessary, but what is remembered will be chosen. That means that whoever is in power will choose what is to be forgotten and what is to be remembered. And there���s always more to forget than to remember. In the particular case of Mozambique, we are forgetting the events that took place after independence, like the Civil War. Seventeen years after the peace treaty (1992), nobody talks about what happened during the war, it���s as if it had never occurred, and obviously that can���t be good because it���s a “false forgetfulness.”

Tania Adam

Does this have to do with traumas?

Mia Cuoto

It has to do with the diversity of voices that make up a nation. The creation of countries is done by excluding “the others,” it���s like saying ���this is our chance.��� This voice is repeated throughout the history of humanity.

Tania Adam

How can these voices be transformed through literature?

Mia Cuoto

The role of literature is essential because it always helps to create a nation. It contributes to building a narrative that can then be shared and studied at schools. Literature can do therapy although it���s not a solution, because it tells our history and allows for a certain catharsis and has the ability to reduce fear. Open political regimes are needed to allow for the emancipation of citizens, and that entails having a well-functioning rule of law. However, I am under the impression that we���re going through another period now, that of the authoritarian state that builds on fear and construes difference as a threat through migrations, Muslims, the “others”��� I think it���s essential that governments think in terms of nations, not elites.

Tania Adam

During my last trip I had the chance to pay a visit to the Leite Couto Foundation. What is its goal?

Mia Cuoto

The foundation aims to continue the work started by my father, the poet Leite Couto, who died five years ago. His death revealed the extent of his support to Mozambican culture. He supported young anonymous people to write and publish. After his death, we received an avalanche of messages from all over the country. On the other hand, I���m used to being stopped on the streets by youngsters who want to show me their texts. So, we created the foundation to continue the task of making their work visible and giving young people opportunities, but not only in the literary field; also in painting, sculpture, music or theatre. In each area, we try to open spaces for public exhibits and this is altruistic, so we also put together exhibits with well-known artists and this allows for some income to sustain the exhibits by young talents. We do the same with books, we���ve already published fourteen books and ten of them were written by authors who had never published before and couldn���t have without help.

Tania Adam

Must they publish in Portuguese?

Mia Cuoto

They can publish in the language of their choice. Unfortunately, I know only of two authors in Mozambique who have dared to write in their mother tongue but it hasn���t worked very well since it���s not only a matter of publishing; you need a market too.

Tania Adam

There is a market under way in Barcelona. You are here to be the speaker of the Sant Jordi Festival, you���re known as a writer here, more than in Madrid.

Mia Cuoto

I���m happy to be here but I think this is not only my work. Africans have worked to open up this space. We help each other. I also wish Mozambique were more proactive about making voices known outside the country.

Tania Adam

In our previous conversation you stated that Africans, people from Mozambique, were lost. While I was in Mozambique, the Catalan philosopher Marina Garc��s published an article called “El dur treball de la cultura” (The Hard Work of Culture), where she drew attention to the importance of culture in transforming subjectivities. That idea of being lost stayed with me for a long time until I came upon her article. Then I understood that perhaps this confusion stems from the cultural deficit leading people to not know where they are from, where they are, let alone where they are going. What can be done to prevent this disorientation?

Mia Cuoto

The answer is complicated; there is so much to be done that I wouldn���t know where to start. In the end, the writers, the artists��� we are to blame for the commercialization of culture and for packaging it into small products. We have also accepted the definition of culture as a ghetto, as a section of the world. We should reclaim culture as a whole. Because for example, the responses to territorial claims, in Spain, Catalonia, in Mozambique, Maputo��� are based on the holistic idea of culture, not as the ghetto we���ve been put into, where we���ve agreed to remain. We are not playing at writing, at making music or poetry; this is more serious. Now, more than ever before, we���ve got to integrate the holistic sense of culture by thinking of radical solutions to the problems we experience. Not everything has to be read in economic terms. It���s important that this position be held together with a guerrilla war of sorts, to alert those in power of the necessary transformations. However, this requires dialogue; we have to listen to one another, not only to those who think like we do.

These are times of stigmatization and polarization, where even those who call for inclusion are unable to engage in conversations with those who don���t share the same political ideology or because they are right-wing extremists. We need to remember that very often people join the far right not because of their political convictions but because of their fears and social threats that are falsely construed.

Tania Adam

You always talk about fear. Actually, I just recently read an article of yours called ���Fortalecer el miedo��� (Strengthening Fear) which was published in La Maleta de Portbou. Why is fear so important from your standpoint?

Mia Cuoto

Fear is biological; it���s an internal alert we all have in order to respond to certain dangers. Current political regimes manage fear well. We are living in a time where people can���t seem to see the future; they perceive survival based on the creation of narrow identities and are pushed towards primitive emotions like fear. They consider that survival is at stake, and that���s an impossible place from which to think as citizens and social agents. And it���s not a matter of individualism. Quite the opposite; it���s belonging to a tribe or to an army that can afford us protection but by annihilating “the other.”

The Mozambican condition has been there before. We killed one another in a civil war that lasted seventeen years. After that, we had no choice but to sit down and engage in dialogue. We sat at a table with those we considered demons and devils. In that dialogue, it was understood that we weren���t that different and we realized that what separated us was construed, invented. Fear is always more invented than it is real.

Tania Adam

Just a few weeks ago, Mozambique was hit by Cyclone Idai, right in the area where you were born, in Beira. I���ve been following the articles in media sources that didn���t exist during previous floods, like in 2000. I mean that the scenarios of cultural representation of the African continent have changed and now there are many voices making complex analysis of the situation. There is no single voice, the voice of the savior that is also the executioner. The new voices address the issue of economic reparations for climate change. I���d like to know what you think about this position. Also, as a biologist, how do you see the present situation in Mozambique? Is the country in danger due to the consequences of climate change?

Mia Cuoto

We have several answers and all of them are true, although they are contradictory. On the one hand, I believe Mozambique should take a stand as not guilty for the climate changes in the region. The culprits must pay compensation, not give aid, which is different. But this position mustn���t exempt us from taking our share of the blame. Mozambique isn���t an industrial country but it produces a lot of CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions through uncontrolled waste burning.

Each year three big cyclones hit the coast of Mozambique. This is a meteorological fact that has gotten worse because of climate change; it���s not new, nor a surprise. As I said, in 1962 I was in a cyclone in Beira, I was barely seven years old but I remember the roofs flying as I watched from my window. It was fascinating but I didn���t understand that what was happening was a tragedy. Cyclones are not exceptions, they���ve been occurring for a long time. So, we can���t keep calling this catastrophes and accidents; they are part of our meteorology. We are in a territory that must have strict response policies for these situations.

Tania Adam

What is the role of the Mozambican state in environmental management?

Mia Cuoto

Our tragedy is that we are dependent on people���s will; there are no state actions that are independent of the people. Now we have an Earth and Environment Minister in Mozambique, Celso Correia, who is making good progress on environmental issues. One of his great achievements is the restriction of logging, and many Chinese companies are starting to leave the country. He is also reclaiming the Natural Parks. My greatest satisfaction would be to see institutions grow beyond the people.

Tania Adam

So, there are national development and environmental protection projects in place?

Mia Cuoto

Yes, and there always have been, but only on paper. What we need is a commitment to implementation.

Tania Adam

Cyclone Idai didn���t come at a good time. What consequences will it have?

Mia Cuoto

Idai arrived at a time when the country���s debt is high, and the existence of a hidden debt was just recently revealed. On the other hand, we were about to start gas production, which was our hope for economic recovery. Of course Idai has hit us economically; my estimation is that we have had a ten-year setback, and it will continue to take its toll. Aid is barely available, and whatever has come our way is not enough. But this is one more African tragedy, it will be forgotten and we���ll have to deal with it on our own. Despite this terrible tragedy, work is being done to improve infrastructures in remote areas. This means there is a policy in place for building and infrastructure to improve the people���s quality of life.

Tania Adam

So the country isn���t paralyzed.

Mia Cuoto

No, not at all, we���re lucky we don���t have oil and have gas instead. Oil encourages the conditions for fast corruption and the absence of state organization. But gas requires a huge investment in infrastructure and entails the creation of small businesses in order to distribute wealth. Now our concern is that they be national businesses, not foreign.

Tania Adam

To get back to your literature, there���s a particular view of your novels in the West regarding magic realism, African mythology. Do you think this view of your work is accurate, or is it judged as remote and exotic?

Mia Cuoto

The main trend is to read my work as exotic, and that perpetuates relations with Africa which develop within the stereotyped frameworks built in the West. It���s also true that these stereotypes are perpetuated by Africans who continue to make the literature that is expected of them: with witch doctors, myths, tribes… But now there are Africans who are opposing these views and introducing other trends and styles. New generations don���t care anymore about what the West expects of them. I feel proud when I hear voices that have risen out of the African ghetto and engage in a dialogue with the world.

Tania Adam

What role do young people have in the future? Although you claim that the idea of future doesn���t exist in African languages.

Mia Cuoto

Yes, but people have the idea of future in mind. Perhaps we should make a distinction between what goes on in rural areas and in the city. For rural peoples the idea of future is what occurs within their own horizon, their sense of the village like a country. Although their perception is changing as mobile phones and the internet broadens their understanding of the world. In contrast, urban youngsters are more demanding, they are no longer satisfied with a political discourse steeped in colonialism and blaming Europe. They want to see transformations and act to achieve them, and I am so happy to see so many cultural and community organizations being created. In Luanda (Angola), for instance, cultural vibrancy is so interesting. This change in mindset is very important because they understand that they don���t need to be sitting around waiting on the state. I often wonder whether there should be state intervention in cultural affairs.

Tania Adam

Well, I think each has a role to play. I guess we have to find the right balance for state cultural intervention. We should avoid what happened in Spain, where there was excessive cultural intervention until the crisis hit and then they didn���t hesitate to cut budgets. I���m so happy to see that civil society is carrying the greatest weight in culture in African countries although I think there should be a bit more state intervention.

Mia Cuoto

Yes, I agree there must be regulations in terms of laws, but the state can���t be a cultural agent like the rest but rather a mediator. Civil society got tired of waiting on the state and is finding its own strategies for self-management. For instance, African musicians are finding their own survival strategies, while creating connections with other countries.

Tania Adam

So relations with neighboring countries are common on a cultural level.

Mia Cuoto

Not that much, really. I wouldn���t trust that Mozambicans know the writer NoViolet Bulawayo, but beyond that, they might be familiar with her although I doubt they���ll read any of her books because they aren���t translated. And if they are, that���ll be in Brazil or Portugal. So, if a Mozambican wants to know a writer from Zimbabwe, they���ll have to come to Europe. What I mean by that is that colonial relations persist. They have to come to the West to understand what���s happening in African literatures. I myself on this trip am looking forward to buying several authors��� books.

Tania Adam

Which ones?

Mia Cuoto

I read a lot of philosophy. As a writer, I���m interested in understanding how thought mechanisms are built through stories. And the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah is really good in this sense. I recommend reading In My Father���s House or The Lies that Bind.

Tania Adam

What other writers of African descent would you recommend?

Mia Cuoto

There is a whole generation of Diaspora Nigerians who publish particularly in the United States; these are a world apart but they are interesting, like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is becoming quite an institution. I recommend Chinua Achebe; it���s such a mistake that they haven���t granted him the Nobel Prize in Literature; he was a great writer of great literary quality. Women are taking strong positions; I am more familiar with those who have been translated into Portuguese, because I prefer to read literature in Portuguese. I was very pleasantly surprised by The Joys of Motherhood by the Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta, as well as by the Ghanaian author Taiye Selasie.

Tania Adam

You just got back from Brazil. What do you think about the situation in the country?

Mia Cuoto

It���s a sick country. I see that people don���t have answers for what���s happening; they���re still in a state of shock. There���s such a sense of desolation that people even break into tears when they talk about the situation. I consider myself a leftist but I see how the mistakes of the left have helped the far right in gaining positions. From Mozambique I watched the rise of Bolsonaro and right-wing polarization while the left was worried about identity issues or cultural appropriation. For me, these are necessary issues but they���re not the big issues. Proof of this is that there���s a far-right government in Brazil now, and the people are broken.

For example, when we talk about the N��gritude movements, my impression is that importing the African American perspective on race distorted the internal struggles that were related. M��tissage or mixed race has disappeared. That means that whoever isn���t white automatically becomes black. Before, Brazil understood its racial complexity as a result of the country���s history; as soon as they imported the US perspective on race it turned into a victory for the far right.

Tania Adam

How does that happen?

Mia Cuoto

Because the race issue gets racialized. That is, it���s racism that produces race, not the other way around. And this principle must be understood in order to take it on. On the other hand, appealing to radical transformation by means of seduction is a must. Seduction can be as firm as accusation; it allows you to say what you must without shouting. The most important things in the world are said by murmuring, in a quiet voice. I think a false radicalization of a problem has been created by importing this idea from the United States. There, for example, if you have a distant ancestor who was black, you are considered black, but it doesn���t work the other way around. If you have a white ancestor, you���re not necessarily considered white. This idea is terribly racist, because it means it’s black blood that stains. These categories mobilize rage and hope very easily while also encouraging blind violence, blind conviction of ideas to defend. We have to understand that many mistakes are committed in a revolution. I myself was a revolutionary, and I made mistakes because I didn���t see them, I was locked up in my own certainty.

Tania Adam

Can the revolution be fought through dialogue, or is it precisely the lack of dialogue that distinguishes revolution? Because if the goal is transformation at all costs, I understand there is no mediation, and soldiers are needed.

Mia Cuoto

Yes, in revolutions there has to be a time when you break away from what there was. For example, when you cut a baby���s umbilical cord this is a violent and revolutionary act. We can���t imagine the violence involved in the birth of a baby, but it has to occur for life to exist. I understand that in the end you have to combine instances when rupture is needed with instances of dialogue.

But in the end we cling to our certainties because we���re afraid of getting lost. Precisely, Africans have an ability that we���ve developed that doesn���t exist in the West, and that���s the ability to embrace the complexity of life. This is closely related to African religiousness, which allows for this expansion. We don���t come from the monotheist thought system that claims to be in possession of the one and only truth; we have the ability to listen to different voices.

September 11, 2019

The white hunter

Topi in the Maasai Mara, Kenya. Image credit Ray in Manila via Flickr (CC).

The wide circulation of photographs of hunters posing proudly alongside the carcass of wild animals killed in trophy hunting expeditions, has been followed by widespread outrage recently. ���Couple shamed for kissing behind dead lion in safari photo��� read one of the headlines on the web portal World News.��One of those most widely circulated was that of Cecil the Lion, a tourist attraction at Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, who reportedly suffered ���incredible cruelty��� during a drawn-out death that took as long as 12 hours.

The nearly universal outrage following such public displays hides a number of ugly truths about trophy hunting. As CBS News��� relatively more nuanced reporting of “the American hunter in a viral photo of slain giraffe��� suggested, trophy hunting also enjoys widespread support. Ironically, ardent supporters of trophy hunting include self-declared conservationists, mostly white men, who defend the practice as the ���If it Pays it Stays��� model of conservation. The CBS News documentary showcases Bubye Valley Conservancy in Zimbabwe, as evidence that this model works. The head of the conservancy claims that this is the only way conservation can be done in the ���third world.����� This is a typical refrain dating to colonial times when the same argument was used to justify imperialist expeditions. For example, the Wildlife Preservation Ordinance (Wildschutzverondnung) of 1896 provided the legal means for establishing wildlife reserves in then Tanganyika (Tanzania), while supporting the ���sport��� hunting industry practiced by Europeans. Colonial conservationists said this was the only way to support conservation in Africa. In the final days of European colonialism, imperial governments acted swiftly to create new forests and wildlife reserves, which led to a ���postwar conservation boom.���

Initiatives such as Bubye Valley Conservancy carry forward the colonial legacies in more ways than may be apparent. Hunting fees from white hunters, received by the white owners of Bubye Hunting Lodge, are used to fund the Bubye anti-poaching task force���led by a white man and staffed by Africans. There are no people of color in positions of power or profit. Villagers appear as the recipients of charity donations of meat from Bubye Hunting Lodge.

In each of the cases profiled on social media, the hunters are white males or females and their hunting grounds are somewhere on the continent of Africa. Trophy hunting thrives on the legacy of colonialism and perpetuates racism on multiple grounds.��Cecil was killed in Zimbabwe by a dentist from Minnesota; a rare giraffe was hunted by a Texan on a hunting expedition in South Africa���from its hide she made decorative pillows, a gun case, and said that she found the slain giraffe meat to be ���delicious���; and the kissing couple who hogged the limelight last month is from Edmonton, Canada and were hunting in the Kalahari Desert in South Africa.

The apparently ���balanced��� coverage of the debates over hunting safaris that CBS News sought to present are problematic on a number of grounds. First, scientific evidence does not support the claims made by the proponents of the ���hunting for conservation��� model. Research by David Coltman and colleagues shows that trophy-harvested rams were of significantly higher genetic ���breeding value��� for weight and horn size, in comparison to the rams that were not harvested. Rams of high breeding value were also shot at an early age and thus did not achieve high reproductive success. Similarly, Peter Lindsey and colleagues analyze the management of lion hunting in Africa and point to the unscientific bases for quota setting, excessive quotas, and off-takes in some countries, and a lack of restrictions on the age of lions that can be hunted.

Such reports also perpetuate the racist foundations of the hunting safari, while promoting faulty solutions to the challenges of wildlife conservation. For instance, the CBS News report got a thumbs up from Amoland Sports Shooting News, which doubles down on the rhetoric that only white people with guns can save wildlife. The reports of a wildlife park in India shooting dead more than 50 people on the suspicion of being poachers also elicited similar responses on the webpages of Bored Panda. The increasing popularity of hunting safaris has been matched by increasingly exclusionary and violent models of conservation, which manifest in the frequent violations of human rights.

The collective sharing of social media outrage helps assuage our sensitivities, but a more effective way would be to stop donating to exclusionary models of conservation that promote hunting expeditions while perpetuating violence against local residents. We must think deeply about how political and economic inequalities contribute to the production of paper parks and exclusionary, violent, and unsustainable models of conservation.

The making of Mugabe’s intolerance

Robert Mugabe at the 12th African Union Summit 2009 in Addis Ababa. Image credit Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. for US Navy (Public Domain).

The recent spate of obituaries on the late Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe have wrestled with efforts to balance the apparent discrepancy between his contributions to the country���s liberation struggle versus his betrayal of human rights and justice while head of Zimbabwe for nearly four decades. However, a closer inspection of Mugabe���s early political record indicates that this chasm is not nearly so paradoxical as the surface view suggests. While revelries of Mugabe���s pan-Africanism, as embodied in a tweet by Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa announcing his predecessor���s death, are largely responsible for the spate of interest in the 95-year-old���s passing, Mugabe���s commitment to the ideology was a double-edged sword.

Pan-Africanism helped ignite Zimbabwe���s independence struggle in the early 1960s, but it also injected a strain of intolerant authoritarianism into the liberation movement of which Mugabe played a leading role from mid-1960. A number of prominent scholars of pan-African governance such as Ali Mazrui, Thandika Mkandawire, and Claude Ake have pointed to the consolidation of authoritarian influences across Africa at this time as pan-African movements became governments and struggled to adjust to new realities.

Mugabe���s quest for unchallenged power as Zimbabwe���s leader following independence in 1980 was profoundly shaped by pan-Africanism���s abhorrence of division and disunity and the ideology���s emphasis on unquestioned unity as the basis of political power in early post-colonial Africa

In late May 1960, Mugabe returned home on leave from his teaching position in Ghana, then the mecca of pan-Africanism. Ghana was led by Kwame Nkrumah, an icon of post-colonial Africa, but a leader swiftly implementing autocratic governance at home. Abroad, Nkrumah believed that multiple anti-colonial liberation movements operating in one territory caused “despondency.” In early July, the world���s attention turned towards one of the most fraught cases of decolonization, in the former Belgian Congo. In the same month, Mugabe formally joined the nationalist struggle, joining the National Democratic Party (NDP) to oppose white settler rule in the then Southern Rhodesia.

By early 1961, the Congo���s Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, was dead due to the intrigue of neocolonial forces and the country was temporarily partitioned. Divisions in Africa escalated with the formation of the Casablanca and Monrovia Groups, which clashed over divergent visions of Africa���s development trajectory. A spirit of contentious pan-Africanism was the background to Mugabe���s formative political years. The lengthy guerrilla war that culminated in Zimbabwe���s negotiated independence only served to further bolster Mugabe���s claim of holding a “degree in violence.”

Mugabe’s first degree in violence

Domestically, Mugabe���s penchant for an intolerant rejection of opposition was clear from as early as 1961, when Zimbabwe���s liberation movement faced its first significant rupture. In June of that year, the NDP faced a challenge to its political primacy from fellow nationalist movement the Zimbabwe National Party. As the NDP���s Publicity Secretary, Mugabe was on the frontline of efforts to thwart the incipient challenge.

An early indication of Mugabe���s inability to accept opposition was evinced in an NDP press release, authored by Mugabe, which rejected the formation of the ZNP and noted that the people ���will not entertain toy parties at the expense of National unity.��� The statement was no idle comment. Just days earlier, the ZNP leadership was forced to abandon its own launch event when its co-founders were violently assaulted by NDP partisans.

The saga with the ZNP also saw Mugabe deploy the political rhetoric on sovereignty and legitimate representation that featured so prominently in his discourse after launching fast-track land reform. The ZNP leader, Patrick Matimba, had resided in Europe and had a Dutch spouse. Mugabe exploited this background, noting in another press release that ���the Africans of this country will never tolerate a situation in which the affairs of their country will be directed by some obscure and remote figure stationed in Amsterdam. We shall not allow this country to be a little province of Holland.���

Competition with the ZNP was strongly manifest in the pan-African sphere. In a major diplomatic coup, the new party secured an invitation to a conference of African nationalist leaders convened by Nkrumah in Ghana. Mugabe was one of the NDP���s representatives���prior to his departure for Ghana he announced that there was no room for both parties to be represented: ���either the ZNP delegation [is in] and we are out or we are in and they are out. There is no question of the two groups being in at the same time.���

Both groups were ultimately recognized at the conference, but in his political speeches back home, Mugabe stressed that the ZNP had been marginalized and that the conference had resolved that colonies should not have multiple independence movements.

Mugabe���s hard-line position came at a cost. His house in the Salisbury (today���s Harare) suburb of Highfield was stoned on several occasions (with his family inside) by individuals allegedly representing the ZNP. He was left a threatening letter by a “General Hokoyo,” the perpetrator, who claimed that the attacks on the ZNP launch had been instigated by Mugabe.

However, Mugabe remained uncompromising. When the ZNP suffered an internal split in September 1962, Mugabe continued to attack new challengers, calling the newly formed Pan-African Socialist Union a grouping of ���political rejects and undesirables.���

When Mugabe and others broke away themselves the following year to form the Zimbabwe African National Union, they became the object of the scorn they had heaped on the ZNP. Mugabe, from a brief exile in Dar-es-Salaam, read helplessly in the newspapers of an account of his house being stoned yet again.

A long shadow over postcolonial Zimbabwe

Nearly two decades of struggle remained before Zimbabwe attained independence under Mugabe���s rule. Amidst the calls for human rights and justice that animated the movement against minority rule, a more sinister strand of intolerance and a search for power at all costs became thoroughly embedded. As the struggle turned toward increasingly violent means, the Zimbabwean nationalist movement relied on ever more oppressive measures. A number of Mugabe���s allies were side-lined or died under mysterious circumstances. Mugabe became increasingly committed to the idea of a military victory to ensure his paramountcy.

In the initial stage of his political career, when the nationalist movement still operated openly before the rise of Ian Smith and the Rhodesian Front, Mugabe participated in a movement which briefly enjoyed unity and had overwhelming support, but which wielded little power to achieve its goals. Pan-Africanism, the most prominent political ideology of the era, indicated that the maintenance of this absolute unity was an essential prerequisite to attaining and holding power.

From 1961 to 1963, Mugabe���s role transformed from enforcing unity in the struggle to leading a faction that decisively ended unity. This contradictory experience and questionable role exerted an indelible impact on Mugabe���s political behavior. Zimbabwe, now under the leadership of Emmerson Mnangagwa, one of Mugabe���s top strongmen, continues to struggle to emerge from the formative shadow of pan-Africanism���s emphasis on unity and power that captured and consumed Mugabe���s political thought.

How Africa shaped Immanuel Wallerstein

Still from Immanuel Wallerstein interview shoot with David Martinez; Yale University, April 20, 2015. Image credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr (CC).

In a reflective essay about his career written in 2000, Immanuel Wallerstein���the American sociologist, economic historian, and world-systems analyst, who died at 88 on August 31 at his home in Connecticut���wrote that ���it was Africa that was responsible for undoing the more stultifying parts of my educational heritage.���

Wallerstein, who grew up in New York City and went to Columbia University, wrote about how, in 1951, he attended an international youth congress, and there met many delegates from Africa, ���most of whom were older than I and already held important positions in their countries��� political arenas.��� The following year, he traveled to Dakar, Senegal for another youth congress. ���Suddenly, at this early point, I found myself amidst the turmoil of what would soon be the independence movements (in this case of French West Africa).��� The result was that Wallerstein ���decided to make Africa the focus of my intellectual concerns, and of my solidarity efforts.���

Surprisingly, this part of his biography has been marginalized in obituaries of Wallerstein. He ended up writing a PhD dissertation that compared the Gold Coast (Ghana) and the Ivory Coast ���in terms of the role voluntary associations played in the rise of the nationalist movements in the two countries.��� He would remain involved in the academic field of African studies for at least the next two decades, becoming president of the African Studies Association in 1973, at a tumultuous time for that organization. Ultimately, he authored several important books on African politics and economics.

Over time, Wallerstein shifted from African studies to interrogate the workings of capitalism more globally, but as he wrote in that same essay, ���I have since moved away from Africa as the empirical locus of my work, but I credit my African studies with opening my eyes both to the burning political issues of the contemporary world and to the scholarly issues of how to analyze the history of the modern worldsystem.���

In 2005, Wallerstein wrote in his book Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity:

[H]aving emerged from colonial rule, Africa is determined to be subject to no one but itself. The depth of its sensitivity to outside control, the suspicion of outside links, should not be misinterpreted, however. It is not a rejection of the world. It is an embrace of it. For African nationalists held, as one of their cardinal criticisms of colonial rule, that it maintained Africans in a cocoon, that the colonial administration hindered contacts with, even knowledge about, areas and peoples outside the particular network.

Wallerstein observed among post-independence Africans ���a strong desire to taste the forbidden fruit, to���enter into relations with all those parts of the world somehow previously withheld from [them].��� Wallerstein���s earliest contributions to African studies may have overstated this ���withholding,��� however. For it was (and remains) in the nature of global capitalism to expand beyond any number of borders, both political and discursive. For instance, the Hollywood film industry, in its various forms, had not been ���withheld��� from Africa prior to independence; its colonizing power was apparent on the continent as early as the 1920s, and it can be seen today in the dominance of Marvel movies in multiplexes from Lagos to Cape Town. Other agents of extractive capitalism���oil and mining companies chief among them���also ���entered into relations��� with Africa well before the acceleration of decolonization, bringing with them all manner of cultural forms and social practices. The fruit that Wallerstein had (and kept) in mind was, then, mostly monetary���a matter of profits withheld, of resources reliably siphoned away.

As Wallerstein once observed, ���the market has been rigged against competition by states and by custom,��� and nowhere is this more apparent than on the African continent. Considered in aggregate, Wallerstein���s decades-spanning research offers an indispensable periodization of Africa���s victimization by, and conflicted internalization of, those aspects of the capitalist world-system that Wallerstein himself did so much to limn. He helpfully identified three distinct phases: 1750���1900 (an epoch dominated by merchant capital); 1900���1975 (characterized by the rise of automobility and petro-chemical industries, with merchant capital increasingly forced to operate alongside industrial-investment capital); and the period after 1975, which Wallerstein, writing in 1976, could only sketch in hypothetical terms, and through recourse to then-emergent discourses of postcoloniality.

Consider, as well, Wallerstein���s remarkable account, in Africa and the Modern World, of the continuities between pre-colonial missionaries and those American anthropologists who, infiltrating Africa in the post-independence period, often acted as ���secular missionaries,��� assuming ���the role of counselor and advisor to African institutions, overtly and covertly, explicitly and implicitly, invited or uninvited.��� Wallerstein���s swipe at the field of anthropology was no simple internecine battle���no crude spat between related academic disciplines���but a serious, even self-critical examination of academe���s complicity in the normalization of capitalism and its effects.

In 1976, Wallerstein recognized (along with the anthropologist, Africanist, and labor studies scholar Peter Gutkind) that the ���dialectics of the political economy of Africa are now as much influenced by��� internal polarization������by, that is, the widening gap between the elite and the impoverished������as by neocolonial hegemony.��� Nearly half a century later, the class-based cleavage that Wallerstein took so seriously is, of course, sharper than ever.

The ongoing relevance of Wallerstein���s work is scarcely in dispute. It is partly rooted in the idea, advanced by Wallerstein and his associates in the early 1980s, that powerful capitalist agents���from Hollywood studios to oil majors���manage to ���constantly reconstitute��� the world-economy in ways that dramatically affect Africa and Africans. It remains, however, necessary to emphasize the continuousness of Africa���s incorporation into international capitalism���into the global political economy���and thus to complicate Wallerstein���s influential account of the ���phases of African involvement��� in the capitalist world-system. After all, as Wallerstein himself averred (in collaboration with Gutkind), ���it is the past, rather than some evolutionary dynamics, which has shaped the present.���

September 10, 2019

It’s time to talk prison abolition in South Africa

Accident At Midrand, Johannesburg. Image credit Paul Saad via Flickr (CC).

On August 7, one week after shopkeepers threw rocks at police vehicles, more than 1500 police officers descended on the central business district of Johannesburg. Part of the province���s much trumpeted operation, O Kae Molao (Where is the Law?), the raid was billed as a success, netting some 600 arrests.

In a press conference, Minister of Police Bheki Cele explained the reason for the raid, ���There is no country that can have parallel governance. There is no country here that can be run by criminals.��� Judging by the minister���s words, one would think that the arrested were involved in staging a coup or, at the very least, a serious criminal enterprise.

So what were these ���criminals��� arrested for? Some for selling counterfeit shoes��or being in the Republic without proper immigration documents, and others for having breakfast without their ID books. Despite these petty offenses, all were subjected to arrest and detention. Some 360 people were detained at the infamous Lindela Repatriation Centre before being deported.

The recent deployment of the South African National Defense Force (SANDF) to the Cape Flats has started a conversation about law enforcement in South Africa. Many have argued strongly against military intervention, with some advocating instead for increased police personnel, engaged in ���intelligent��� and ���visible��� policing. The dismal example of O Kae Molao should give us pause when considering the merits of these well-intentioned calls for fewer troops, but more cops. We should ask ourselves: can policing deliver justice in South Africa?

For the vast majority of the country���s history, the answer to that question has been, decidedly, no. From mine police to Vlakplaas, the police and its brother institution, the prison, have been instrumental to the advance of capital accumulation and the maintenance of settler rule. With the transition to democratic rule, South African Police Service (SAPS) was meant to shed its ugly history and carry out a form of ���human rights policing.��� But as Julia Hornberger shows in her book on Johannesburg SAPS, officers found the ideals of ���human rights policing��� difficult to reconcile with the demands of the job. Extralegal violence, they insisted, was essential to policing.

Recent government statistics suggest that cops across the country agree. Last year, officers were accused in 217 cases of torture and 3,661 of assault. The same report records that SAPS officers killed 558 people. To put that in perspective, SAPS kills three times more people per capita than American police. The situation in the country���s overcrowded jails, prisons, and immigrant detention facilities is similarly grim.

These abuses are not aberrations nor, as some might suggest, primarily a result of corruption or state failure. They are inherent in institutions designed to capture and cage human beings. History suggests that will not be rectified by more numerous or ���efficient��� personnel. According to recent budgets and statistics, government has increased police personnel by 50% since 2002 and increased its policing budget sevenfold since 1994. And yet, discontent with the police is boiling over.

Although crime policy has arrived at a cul-de-sac, there is a path forward. In response to the American prison industrial complex, scholars and organizers, led predominantly by black women, have started to push for prison abolition. Arguing that more punitive responses to crime do not deliver safety and often breed greater insecurity, abolitionists work to reduce the structural conditions that give rise to social harm, while responding to incidents of social harm in non-punitive ways. Abolition is not a demand that all prisons be bulldozed tomorrow. It is, as professor Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, ���a theory of change.��� It imagines the sort of world necessary to make prisons obsolete and sets out to bring that world into being. And whereas liberal reform efforts have tended to deepen state violence, abolitionists have opposed any expansion of the state���s use of ���prisons as catchall solutions for social problems.���

The nascent South African left should incorporate abolitionist principles into its long-term political vision. This will not be easy. African National Congress-led governance has long severed economic justice from criminal justice, in an attempt to obscure the social bases of crime. Decades of failed crime policy and a pervasive sense that ���crime is out of control��� have encouraged much of the population to take up the idea that only more punitive measures will lead to greater safety.

But never in the post-apartheid period has the need for an abolitionist politics been more urgent. As Richard Pithouse suggests, the scale of the crisis has generated a dark mood ripe for authoritarian solutions. And while it is unlikely that South Africa is headed for American-style mass incarceration, calls for more police will result in more indiscriminate, punitive policing as the SAPS attempts to prove it can ���keep order��� amidst crisis. As O Kae Molao and the raid on Cissie Gool House demonstrates, the victims of the government���s ���war on criminality��� will be poor and working-class people trying to survive and organize under conditions of artificial scarcity.

Looking back on the wreckage of post-apartheid crime policy, the left can make a compelling case for abolition. It can make clear that those politicians who tout ���law-and-order��� have nothing to offer materially; and that every rand spent on rubber bullets would be better used to expand access to health care, education, jobs, and social grants. It should remind people that before colonization, Africans got along just fine without criminal law, prisons, or police.

September 9, 2019

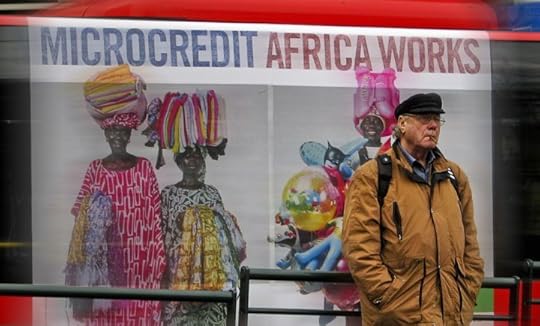

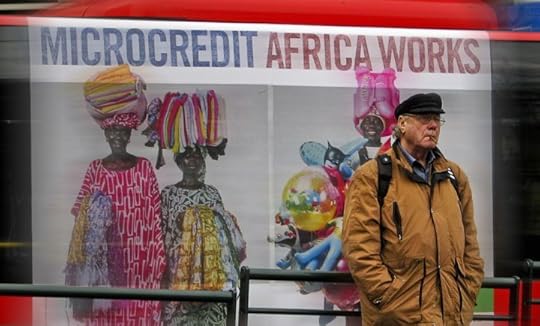

The problem with microcredit in Africa

Microcredits work. Image credit Tjook via Flickr (CC).