Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 147

December 1, 2020

After repatriation, what next?

Benin Bronzes, at the British Museum. Image credit Raj Patel via Flickr CC.

In the film ���Black Panther,��� the villain Eric Killmonger, played by Michael B. Jordan, asks a British museum curator, eyeing African artworks, ���How do you think your ancestors got these? You think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?��� As Killmonger reminds us, an enormous volume of cultural artifacts have been taken from Africa. Items gathered by theft, coercion, and looting, as well as for the purpose of research supporting scientific racism, are increasingly recognized as illegitimately appropriated and due to return. The repatriation debate is now high-profile enough to make it into a popular film, along with books by academics, scholarly journals, and popular websites.

The Benin Bronzes are one high-profile case. The sculptures, looted by British military forces from Benin City in 1897,�� are now held by institutions and private owners all over the world and, despite the obvious way in which they were stolen, are returning only in a slow, piecemeal fashion. The British Museum, which holds a large collection, continues to resist their return. At the same time as repatriation remains contentious in some spaces, however, it is also gaining ground. Institutions such as the Smithsonian in the US, Dutch heritage institutions, and the German and French governments have made commitments to returning at least some types of cultural property. Even if such efforts are halting or half-hearted, the fact that states and institutions are now feeling the obligation to publicly indicate their repatriation efforts is a positive sign for the process���s advocates, reflecting a broader shift in its favor.

Still, the returns themselves are only part of the story. What happens next?

This question requires us to think about the role of cultural artifacts in contemporary societies. The Senegalese scholar, Felwine Sarr, and French counterpart, B��n��dicte Savoy, the authors of Restitution Report commissioned by the French government, say that African nations face a double task: first, restoring memory through reclaiming heritage, and second, a process of ���self-reinvention��� that connects reclaimed artifacts to present-day societies and their challenges.

Sarr and Savoy���s suggestion is something that scholars of history and heritage have long called the construction of a ���usable past��� for a nation, something that can be mobilized to address the concerns of the present. The first president of Botswana, Seretse Khama, noted how key this project was to newly independent African countries: ���We should write our own history books to prove that we did have a past, and that it was a past that was just as worth writing and learning about as any other. We must do this for the simple reason that a nation without a past is a lost nation, and a people without a past are a people without a soul.���

Tangible cultural heritage is a materialization of the past. It makes history visibly, palpably available to contemporary people. Importantly, cultural heritage is not a static or stagnant collection of objects, but a living construction. As the heritage scholar Rodney Harrison puts it, ���Heritage is not a passive process of simply preserving things from the past that remain, but an active process of assembling a series of objects, places and practices that we choose to hold up as a mirror to the present, associated with a particular set of values that we wish to take with us into the future.��� The return of cultural artifacts provides objects around which what Sarr and Savoy call the ���project for the future��� can coalesce.

What might this project for the future be? Some results of repatriation are evident already: in South Africa, the return of the bodies of a San couple provided closure for their families and advanced the decolonial project. Other countries provide useful parallel examples. In the US, the Cherokee anthropologist Russell Thornton has illustrated the role of returns in healing the cultural trauma of Native American communities. We can look, too, to the ways in which African nations are currently utilizing heritage in the interest of present and future societies. Heritage sites are used for economic development and recognition via World Heritage listing, while communities can reconnect with their pasts through archaeology from the ground up.

Such examples indicate that African nations are already managing their own heritage and managing it well. One of the arguments against repatriation is that African countries lack the capacity to adequately care for fragile items. But impressive institutions such as Dakar���s Museum of Black Civilizations refute this claim. (Indeed, the global North should consider whether its own profiting from colonial theft of heritage brings an ethical obligation to make amends through material support for resourcing and training African heritage institutions.) What Africa lacks is not the ability to manage heritage, but the heritage itself: the Benin Dialogue Group���s planned Royal Museum for dispersed heritage will create a home for repatriated objects, awaiting only the actual returns of what was looted in 1897. Stolen artifacts can return to nations more than capable of both caring for and utilizing them going forward.

After repatriation, then, the next question for African countries is about the future they wish to make through heritage, including the heritage that they are now reclaiming. While researching the Rwandan state heritage sector, I met government employees who were finding ways to make heritage work. In a country consumed with the pursuit of development, these practitioners investigated how heritage could contribute, as one told me, to ���the future we want.��� This meant giving Rwandans evidence, through museums and public history, of a usable past of which they could be proud���one that would counteract the ethnic divisions instituted by colonialism. Heritage was not just instantiations of history, nor was it a collection of inanimate objects: it was the project of making a new future for Rwanda.

The discussion of repatriation must not stop at simple returns, because these are not the endpoint of the process. They are only the beginning of a new one: mobilizing heritage as the material foundation for constructing understandings of the past that matter to the present and future. Repatriation is, in part, the righting (limited as it may be) of historic wrongs through the recognition of colonial injustice and the return of stolen heritage. But in enabling new narratives that are based on the material past and also responsive to the needs of the present, repatriation opens up new possibilities for the futures that African nations will make for themselves.

Mozambique���s borders

Photo by Dimitry B on Unsplash

This post is part of our series, ���Histories of Refuge,��� made up of essays from participants in the Rethinking Refuge Workshop. It is edited by historian Madina Thiam.

During the period prior to the setting up of the Portuguese colonial administration in southeast Africa, there were important waves of forced migrations caused by, firstly, the Mfecane, and secondly the defeat of King Ngungunhane in 1895, and the subsequent overthrow of the Gaza Empire. The Mfecane was a period of economic and political disruption and mass displacement and migration in Southern Africa, which occurred in the 1820s and 1830s across the region of the Pongola River in the current South Africa.

Graeme Rodgers notes that:

The wars and upheavals of the nineteenth century formed the basis for two dominant images of territory held by Mozambicans as well as by South Africans: the image of Gaza as the authentic territory of the Shangaan people and the historical image of Tsonga-speaking groups taking refuge from Mozambique to South Africa.

Throughout the colonial period, migration allowed people to escape harsh conditions providing the opportunity to access social services, markets, and workplaces beyond Mozambique���s borders. In fact, the period between 1930 and 1974 was characterized by the institutionalization and strengthening of the Estado Novo, an authoritarian, nationalist, traditionalist, and corporatist period, and fascism in Portugal. This period was also marked by the reinforcement of Portuguese colonialism in Mozambique. There was a marked exploitation of the African labor force in the countryside, increasing emigration of African labor to the plantations and mines in neighboring countries and the imposition of forced cultures on peasants. Peasants waged resistance against the imposition of forced cultures and forced labor, commonly known as xibalo, forcing them to flee to both Eswatini (Swaziland) and South Africa.

When the armed struggle against the Portuguese colonial rule erupted in 1964, resulting in the intensification of counter-insurgence activities by Portuguese secret police, there was a wave of forced migrants who sought refuge in Eswatini and South Africa because they were militants of the anticolonial Frelimo and feared being arrested by the colonial authorities.

Shortly after independence, the country was engulfed in a bloody civil war. Forced migration flows that occurred during the civil war which deserved much attention by scholars featured continuities and contrasts with previous patterns. During the civil war, Mozambique���s government tried to concentrate the population in villages as a way to remove them from Renamo���s influence. This process was very coercive and had undesirable impacts for the government. As a result, thousands of people fled to neighboring countries as these settlements were created. Also Renamo forced exodus to South Africa or Eswatini as it feared people would inform government soldiers of its guerillas��� whereabouts. Renamo relied on guides who provided safe passage for those willingly wanted to leave the country either to Eswatini or South Africa. Such guides played multiple roles as rebels, cross-border guides, and traders. They also kept links with both sides at war supplying Frelimo soldiers as well as the rebels with basic items such as salt and shoes.

Those who fled to South Africa during the insurgency by Renamo were not granted refugee status according to international conventions but were instead treated as illegal immigrants as the apartheid government denied to recognize them as international refugees. Therefore, the former Mozambican refugees were never institutionally separated from the local population and were not given much material assistance, except for the limited food aid from the churches.

The majority, however, were allowed to settle on a temporary basis by the former Shaangan ���homeland��� governments of Gazankulu, the Zulu in Kwazulu and in Eswatini in kaNgwane, which provided them access to land. Homeland authorities actively encouraged the Mozambican settlement in their territories because, as Graeme Rodgers notes, ���local chiefs capitalized on the opportunity of expanding their local support bases and in the other, it represented a gesture of independence from the central government in which they were politically and economically reliant.��� However, these refugees when found outside homeland borders were arrested and deported by the national authorities.

Differently, in Eswatini refugees were sent to camps. Some refugee camps were active bases of political activities, mobilization, recruitment, and some logistic support for Renamo. Eswatini���s government tolerated Renamo���s activities among refugees. Renamo���s cross border networks also spanned the South African borders. In addition to linkages with the South African military, there were a range of other networks involving self-settled refugee communities. The fall of apartheid in South Africa had a significant impact on Mozambicans who had sought refuge in the country due to civil war.

This discussion has shown that forced migration and refuge-seeking has been a central feature in southern Mozambique displaying patterns of continuities and changes throughout pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial periods. Pre-colonial African states produced waves of forced migrants who sought refuge and asylum in other states. Interstate conflicts and wars caused by expansionist pretensions created waves of forced and internally displaced migrants. Several regions of the African continent experienced long before the colonization great upheavals that would most probably be described today as humanitarian crises, and the Africans of the time reacted with the means then available as was the case of Mfecane.

The imposition of the colonial system changed the nature of forced displacement in southern Africa depending if the partition was peaceful or violent. Formerly rival ethnic groups fell in the same geographic space and those which shared culture and identities were divided. Also land expropriation led to massive internal displacements. Throughout the colonial period, migration allowed people to escape harsh conditions providing the opportunity to access social services, markets, and workplaces outside Mozambique���s borders.

If during colonial period, forced labor, mandatory cultures, hut tax, and the action of the International Police of the State Defence (PIDE) were determining factors for the forced migration of families to South Africa and Eswathini, in post-independence period it was the outbreak of the civil war waged by Renamo (Mozambique National Resistance) supported by racist and minority regimes of Ian Smith’s in Rhodesia and apartheid in South Africa.

Since pre-colonial times, southern Mozambique has been a region of recurrent violence and forced displacements. During the pre-colonial period, inter-state wars led to massive forced migration waves. The colonial period witnessed the implementation of legislation by Portuguese authorities based on coercion in order to intensify economic exploitation of the colony. Such measures led people to flee to neighboring countries (South Africa and Eswathini and nearby the then-British colonies of South Rhodesia and Niassaland). Post-independence legislation aimed at controlling people���s movements, forced villagization, and civil war punishment showed patterns of continuity of colonial times. Such continuities generated opposition, and resentments after independence which culminated with forced migration flows.

November 30, 2020

The greatest of all time

Sean in Marseilles with Maradona.

Thomas Sankara, who led a revolution in Upper Volta and renamed the country Burkina Faso, once said ���You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future.��� Sankara was talking about the political project he led for four years in Burkina Faso in the mid-1980s���in which he wanted to break his country���s dependence on the West, become self-sufficient, smash patriarchy and break the power of landowners over rural Burkinabe. But he may as well have been talking about Diego Maradona.

Arguably football���s greatest of all time, or G.O.A.T., Maradona was probably the first global football star of the television age. Many people swore by Pele as the best footballer of all time, but few of them actually saw him play live. Most of his thousand plus goals were scored in Brazil���s domestic leagues. You could only read about it. Not so Maradona. From the moment he made his debut in the 1982 World Cup (he was too young to be included in Argentina���s championship squad of 1978), transferred to Barcelona, became a legend at Napoli (a European championship and two Serie A titles at an unfancied club from a poor city) and in-between led (that���s literally) Argentina to a World Cup title in 1986, it was clear that he was something else.

Off the field, Maradona scandalized those in power. He sided with the poor. Maradona, in the words of Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, had ���committed the sin of being the best, the crime of speaking out about things the powerful wanted kept quiet.��� He clashed with FIFA (the corrupt body that controls world football) and with the United States (that���s also where his international career ended).

We will be joined by two guests: Pablo Medina Uribe is a Colombian multimedia journalist and writer based in Bogota. He covers politics, sports, culture, their intersections, and beyond. Worked in online media, publishing, radio, TV, and apps. Interested in developing technology for telling better stories. Tony Karon teaches on the politics of global soccer in the Graduate Program in International Affairs at the New School in New York. He is editorial lead at AJ Plus and before that spent 15 years at TIME magazine, where he was a senior editor.

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

November 29, 2020

The regulatory chill

Photo by Nelly Antoniadou on Unsplash

This post is part of our series “Climate Politricks.”

In 2014, Union Fenosa Gas (UFG), a Spanish company, filed an international arbitration case against the Government of Egypt at the World Bank���s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). After four years of arbitration, the government was asked to pay the investors more than USD2 billion in compensation���plus interest and associated legal and arbitration costs.

What allowed UFG to file an arbitration claim against Egypt is a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) signed between Egypt and Spain in 1992. The BITs are some of the most potent international legal instruments. There are more than 2,600 of them, and most contain investor-state dispute-resolution (ISDS) provisions that allow investors to seek compensations in one of a few secretive arbitral tribunals���should they deem their investment to have been expropriated by a host government. One of such tribunal systems is administered by the World Bank-linked ICSID.

Provisions under ISDS are non-reciprocal: states cannot file claims against investors. States also cannot ignore claims filed against them or refuse to ignore rulings of arbitral tribunals. If they do, the investor could get an arbitral court decision that allows it to seize the state���s commercial assets in almost any jurisdiction. The costs to states are more than just the compensations; the cost of participation in an arbitration process under the ICSID tribunal system is on the average almost USD5 million for respondents (states).

Although African states have been on the receiving end of an increasing number of investor claims (more than 15% in the ICSID system), Africans make up only 2% of arbitrators, conciliators and ad-hoc committee members. Tribunals are constituted ad-hoc, which adds to the unpredictable nature and the high fees the few specialists who can serve on them are able to charge.

The fear of arbitration claims has resulted in ���regulatory chill,��� where governments are afraid to make policy changes for fear that they might be deemed as expropriation if the changes adversely affect an investor. This fear came up, for example, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the emergency measures needed to address health, economic and financial implications triggered by the pandemic, governments are afraid that they might end up with expensive investor ISDS claims���as the emergency measures might be considered as expropriation. This might explain the muted policy response to the pandemic across many jurisdictions.

The climate change connection

The ISDS���s are also influencing measures to address climate change. A recent report by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) states that if proposed actions to keep global warming to between 1.5��C and 2��C above preindustrial levels are implemented, oil and gas worth around USD 5 trillion dollars will become stranded assets. That is, it will no longer be commercially viable to exploit them, in this case due to the adoption of policies that will help address climate change. According to the report, implementing measures that strand assets could open states up to ISDS claims.

African governments that depend on natural resources are therefore facing risks on several fronts. According to a discussion paper from the United Nations University Institute for Natural Resources in Africa (UNU-INRA), African countries that depend on natural resources (nine out of 10 countries) face the risk of drastic reduction in revenues, which will negatively impact social spending and adversely affect the implementation of climate adaptation measures.

If they choose to keep developing fossil fuels, they risk being locked out of newer, cleaner technologies while literally fueling further climate breakdown, of which Africa is already among the hardest hit regions with serious implications for agriculture, livelihoods, water supplies, and food security among many others. On the other hand, according to the IIED report, if they adopt measures that strand assets, they are open to arbitration claims and litigations.

What is the way out?

The conversation regarding climate change, adaptation measures and stranded assets as they relate to Africa, which has been advanced by UNU-INRA, needs to also include the risk of ISDS claims. Research that connects the dots and quantifies the implication of the interaction of these aspects needs to be done. Such research could come up with possible policy options for African governments, as well as negotiation positions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

In the meantime, the ISDS aspect, which encompasses much more than climate adaptation measures and threatens sovereign rights of states to make policies, can already be addressed. Aside from unilateral decisions to terminate BITs, which South Africa, Namibia, and Tanzania have done (although Tanzania still had claims filed against it under the terminated treaty) there are currently two opportunities to do this on a continental level.

First, African countries need to make a forceful contribution to the ongoing negotiations on reforming the ISDS framework being coordinated by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). The European Union has proposed a new Multilateral Investment Court, which would do away with ad-hoc tribunals and instead create a formal court. Tellingly, this proposal does not include a reciprocal arrangement���the EU recently cancelled all BITs among EU members; and its entities are more likely to be claimants than respondents.

South Africa has made a powerful submission to UNCITRAL. It seeks a new paradigm for understanding foreign direct investments (FDI) and investment treaties���including a proposal to grants rights to other stakeholders to file claims against investors. Africa as a whole should also make a submission. But first, Africa needs to craft its own position.

Negotiations for the Investment Protocol of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers an opportunity to consider what an African position on ISDS would be. A new AfCFTA Investment Protocol could rationalize existing intra-African BITs (there are more than 170 of them) and other regional investment legal frameworks.

More importantly, although the protocol will only cover intra-African investment, it can already spell out certain principles, such as investor obligations and the protection of policy space. The template can then serve as a model for investment agreements between African states and third parties. It could even be something around which an African submission to the UNCITRAL could be based. The shadowy world of BITs is in definite need of some African alternatives.

November 26, 2020

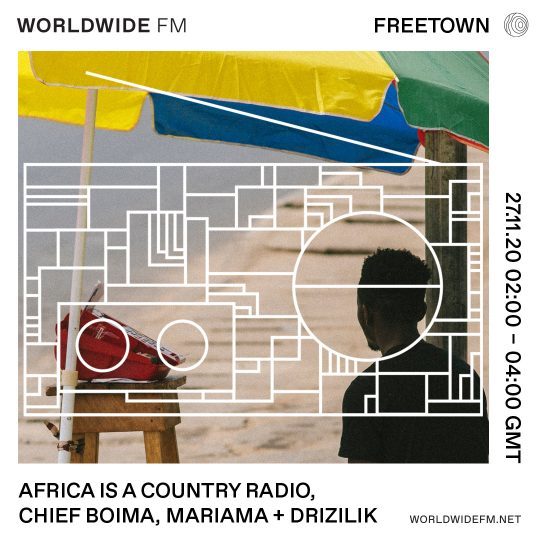

Freetown’s musical soup

Photo by Random Institute on Unsplash

In our last season of Africa Is a Country Radio, we explored the idea of international blackness with music and interviews on black identity from the United States to Latin America to Europe. It was recorded in conjunction with my work on the INTL BLK platform and featured several friends and collaborators in Los Angeles. After a few months break, we are now back with a new season and a new home, London-based web radio station Worldwide FM.

This season���s theme will take inspiration from Paul Gilroy who suggests that to understand black culture, we must focus on the routes of exchange, rather than the perceived roots of culture to understand how hybridity and the navigation of empire have shaped modernity, the nation, and identity in the world today. Our focus will be port cities as connecting nodes in the international network of cultural exchange that is the Black Atlantic. Each month we will take a deeper dive into the music and cultural politics of a different port city on the African continent.

In episode one, we will take a close look at the history and cultural stew that makes up the city of Freetown, Sierra Leone. Founded in 1792 as a colony for freed former slaves from British North America, and then serving as a site of repatriation for enslaved Africans freed by the British military in the 19th century, as well as serving as the capital of colonial British West Africa, Freetown is a quintessential Black Atlantic city. It also happens to be a place that is close to my own heart, and remains significant in my own identity formation and cultural production.

In the post-independence period, after experiencing the pangs that come along with the formation of a nation, this hybrid cultural city is now trying to wrestle with its place in the 21st century global economy. With a large diaspora, partially due to an 11 year civil war from 1991-2002, the international connections are just as strong as they were at the country���s founding. So in this show we take a look at that history of influences that make up Freetown culture, and how that legacy manifests today.

The show features special guests, journalist Mariama Wurie (@mariama.wurie) a Sierra Leonean journalist and creative who reports on cultural happenings for CNN and other outlets, and Benjamin Menelik George, known professionally as Drizilik (@drizilik), one of the most popular artists in the country, and a leader in the latest generation of Freetonian musicians.

Tune in on Friday, November 27th from 2pm-4pm Freetown and UK time (9am-11am EST) on the Worldwide FM live feed. If you miss it, visit our show page where the show will be archived. For those of you following us on Mixcloud the shows will continue to be reposted there.

November 25, 2020

Christianity and the alienation of Africans

Aksum, Ethiopia. Image credit Rod Waddington via Flickr CC.

Two recent stories from Africa, both connected to the just ended US presidential elections, have led some observers to remark that Christianity seems to be alienating Africans in ways that prevent them from having a clearer view of their own interests.

The first story was a BBC report detailing how some African evangelical leaders, mostly from Kenya and Nigeria, were praying for the incumbent Donald Trump to defeat his challenger, Joe Biden. The rationale these leaders gave for supporting Trump was one directly culled from the issues Christians in America have been debating, including abortion and religious freedom. The African evangelical leaders praised Trump for promoting anti-abortion policies and for being a defender of Christians, even though the issues of abortion and religious freedom are not the dominant issues Christians in Nigeria and Kenya are facing.

Shortly following this report, a video of some Christians in Nigeria marching in support of Donald Trump circulated on the Internet, and Donald Trump himself retweeted the clip with the response, ���A parade for me in Nigeria, a great honor!��� This support for Trump was jarring given that he had disparaged African countries and expressed what may be described as racist sentiments about them. That African Christians would be supporting a person who clearly could care less about them struck many as symptomatic of the ways that Christianity leads Africans to militate against their own interests.

That Christianity has had deracinating and other harmful effects on Africans is not a new insight. The problematic effects have been recognized since at least the 19th century both by those who embrace Christianity and those who do not. In an 1881 essay entitled ���The Aims and Methods of a Liberal Education for Africans,��� presented at Liberia College (now the University of Liberia), the Caribbean-born Liberian and Presbyterian churchman, Edward Blyden, decried ���the treatment which our own race and other so-called inferior races have received from Christian nations.��� He noted how the ���sword of the conqueror and the cries of the conquered have attended or preceded the introduction��� of Western Christianity into non-Western lands. Also, the theme has been central to much of African literature, especially exemplified in works of authors such as Ngugi wa Thiongo, Wole Sonyinka, Mongo Beti, and Chinua Achebe, among others. For many of these writers, Christianity has not only divided Africans but also diminished their being in the world. In his now classic work called ���Song of Lawino,��� which pits a Westernized and Christianized husband against his wife who stands for indigenous Africa, the Ugandan scholar Okot p���Bitek critiques Christianity for turning Africans into ���parrots,��� who unquestioningly adhere to a religion they do not understand, despising their own traditions in the process. Even scholars of African Christianity, such as Jesse Mugambi, Musa Dube, Tinyiko Maluleke and Emmanuel Katongole, among others, have wondered aloud whether Christianity can be trusted to bring healing to some of the ills that the continent faces. Others, such as the South African theologian Gabriel Setiloane, have even wondered whether Africans should continue to be Christians. These are questions that still largely remain unanswered, especially given the checkered history of modern Christianity in the continent.

Yet, it is recognized that Christianity has been gaining significant ground in Africa, so much so that the continent is now home to more Christians than any other continent in the world. Given that Christianity has taken root, many now acknowledge that it is only by Africanizing Christianity that the religion may better account for the interests of Africans, rather than placing Africans at the mercy of external machinations. This project of Africanizing Christianity has a long history in the continent but in a recent book, African Catholic: Decolonization and the Transformation of the Church, the historian Elizabeth Foster captures how Africanizing Christianity may enable Africans not only to transform their continent but also to transform Christianity as a whole. Focusing on the Catholic tradition, the book explores how West African Catholics pushed the French colonial Catholic Church in West Africa to see the wisdom of decolonization, thus helping to decolonize not only the continent but also the church. This is still an unfinished business.

At a time when most churches in Africa are led by Africans, there still exist Christian ways of thinking that are anti-African. This is especially seen in churches that demonize African indigenous traditions, turning African deities into devils and ancestors into sources of demonic blockages. It seems that in these churches, the only way to be Christian is to seek to untether oneself from one���s indigenous background. Because of their connection to churches in Europe and the US, many of these churches continue to see issues raised by churches in Euro-America as issues that should be of central Christian concern. This is how abortion and religious freedom came to be central to some churches in Nigeria and Kenya, whereas they are not the central issues for most Christians in these countries. This anti-African Christian imagination seems to be the source of spectacle, such as those detailed at the beginning of this piece. Challenging this anti-African Christian imagination is one way of checking a Christianity that appears to alienate Africans from their being in the world.

November 24, 2020

How to think about Ethiopian politics today

Photo by Daggy J Ali on Unsplash

While much of the world was preoccupied with the elections in the United States, Ethiopia careened toward civil war. Ethiopia���s Nobel laureate, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, appears poised to undo the political settlement of 1991, one that ended decades of civil war and ushered in the ethnic federalist state. During the 2010s, as Ethiopia enjoyed impressive economic growth rates, it appeared that the country had figured out how to create a successful development state while acknowledging the aspirations of the many nationalities that make up Ethiopia. Yet, even as an economic miracle unfolded, many labeled Meles Zenawi���s state as illiberal and authoritarian. Others claimed that Zenawi���s Ethiopia was an ethnic federation in name-only, but in practice that the Ethiopian People���s Democratic Front was dominated by the Tigray minority through the vehicle of Tigray���s People Liberation Front. It is for this reason that many inside and outside of Ethiopia cheered when Abiy Ahmed came to power on the back of protests by the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, the Oromo, in 2018. He promised to liberalize the economy, democratize the state and to make peace with Eritrea.

Instead as fighting rages across Tigray, Abiy Ahmed has brought to the fore the central questions of Ethiopian political theory: should the Ethiopian state be a federalist state or a unitary state. The second question of the nationalities includes whether sovereignty lies with the different ethnic groups inside of Ethiopia or with the state itself. The political theorist Elleni Centime Zeleke in her excellent book Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production,1964-2016, demonstrates how these questions date back to the debates of the Ethiopian Student Movement in the 1960s and then proceed into the present. Alex de Waal the veteran political analyst of the Horn of Africa has called Zenawi, ���the ablest political intellectual of his generation.��� If Meles and the Ethiopian People���s Democratic Revolutionary Front were so politically and economically savvy, then the question for many outsiders today is why does the Ethiopian political system appear to be teetering on the brink either of civil war or the consolidation of power by Ahmed?

The TPLF veteran Mulugeta Berhe, in an interview with De Waal, said that part of the reason that the current crisis in Ethiopia is so difficult to understand for outside analysts is our ���lack of thought on the role of theory in African rebellions.��� Berhe emphasizes the role of ideology in the organizing of the Ethiopian Civil War, and that the aim of the TPLF and its allies was not so much to take over the state, but to fundamentally reimagine it as a multi-national state in which sovereignty rests with the different nationalities. Zeleke���s work shows how the student movement used social science discourse to reimagine Ethiopia, and then how the forms of social science ultimately limited what was imaginable.

In order to revisit the question of what futures the social sciences made possible for the Ethiopian polity and which futures the social sciences foreclosed, Zeleke focuses on the thoughts and writings of the Ethiopian Student Movement, a transnational collection of Ethiopian post-secondary students studying at home, in Europe, and in North America between 1964 and 1974. A close reading of the journals and writings of these students provides the heart of her captivating and provocative book. Zeleke shows how the intellectual culture of the movement and its debates have continued to reverberate throughout Ethiopia���s political culture to this day.

She pays particular attention in chapters four and five to the 2005 federal elections and the 21st century debates about redeveloping Ethiopia���s capital Addis Ababa in order to propel the developmental state. She writes of the Ethiopian Student Movement that, ���if the virtue of the student movement from the 1960s and 1970s was that it attempted to theorize Ethiopia���s place within global structural process ��� they also used the ���eternal��� laws of the social sciences as weapons to silence their opponents.��� Zeleke creates a fascinating account of how Ethiopian students refashioned Marxist-Leninist categories like the feudal, or reimagined the nationalities question in order to make their own situation fit the rules of historical materialism. In the process, intellectuals writing in journals such as Challenge were taking part in a global process of reimagining Marxism by theorizing at what Stuart Hall calls ���the limit case.���

I recently edited an online H-Diplo roundtable on Zeleke���s book. The participants were Samar Al-Bulushi (Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine), Adom Getachew (Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago) and Wendell Marsh (Assistant Professor of African American and African Studies at Rutgers University���Newark). All three reviewers commended Zeleke on the ambition and scope of her work. Marsh writes that he reads the book ���as a humanistic inquiry into the social sciences as a knowledge-form.��� He goes on to say that reading Ethiopia in Theory provides a way of thinking through ���what it means to be human in a world that has been made by the social sciences.��� Getachew commends Zeleke for her rejection of narratives of Ethiopian exceptionalism, and for making visible the global circulation of ideas that shaped Ethiopian political and social thought leading up to the 1974 revolution and its aftermaths. However, she argues that Zeleke moves too quickly from a discussion of the intellectual context of the Ethiopian Student Movement to its aftereffects. She asks how we as intellectual historians or political theorists establish relationships of influence. Al-Bulushi writes that Zeleke eloquently demonstrates that the ���persistent questions about what it means to decolonize knowledge production in African studies can only be addressed ���by situating knowledge production in Africa within the historical processes that have led to contemporary political forms.������ Samar then goes on to highlight the ways in which Zeleke argues that there is a ���continued association of Western whiteness with modern knowledge and expertise��� and that this explains the failure of Ethiopian social sciences to completely grasp its own realities.

Picking up on questions of the Whiteness of the social sciences, Zeleke in her conclusion and her response reminds us how questions of disciplinary standards and objectivity have been marshalled to silence Black scholars, and to prevent the development of social sciences in Africa that were grounded in African and African diaspora realities. In the final analysis, all of the reviewers agree that Ethiopia in Theory is a milestone in the collective project of reimagining the social sciences and reasserting the fundamental connection between theory and embodied praxis.

Finally building on the work of Ugandan political scientist Mahmood Mamdani but stretching it to Hall���s ���limit case,��� Zeleke asks how should we understand the persistent crisis of the African state? Is its root in the survival of ���indirect rule,��� the persistence of ���customary law,��� and the reification of tribe, ethnicity, or nationalities? In the case of Ethiopia, these are not merely academic questions. If the answer is yes, then it is easy to understand the critics of EPDRF���s ethnic federalism and Abiy Ahmed���s attempts to stamp out the intransigence of the TPLF. The politicization of ethnicity becomes the explanations for Ethiopia���s instability. The answer is to create a post-ethnic politics perhaps represented by Ahmed���s Prosperity Party. Yet the frailty of this solution is symbolized by Ahmed���s decision to indefinitely postpone the federal elections another beginning point for the current crisis. Alternatively, Zeleke argues that it is insufficient to isolate ���ethnic federalism��� and the legacy of European colonialism as the roots of Ethiopia���s crises. Instead, she argues in line with scholars of global capitalism in India and China, such as Andrew Liu, that we must return to a study of political economy in order to see the ways in which capitalism inherently governs through systems of difference and hierarchy.

Therefore, the dilemma of Ethiopia and by extension contemporary Africa is not simply to escape the legacies of colonialism but to transcend its peripheral inclusion into the capitalist world-economy. It is impossible to democratize Ethiopia without addressing the continuing economic marginalization of the vast majority of the Ethiopian people, whether or not the sources of these marginalizations reside within the Ethiopian state or in the wider global economy.

November 23, 2020

The passing of Jerry John Rawlings

Jerry Rawlings in Somalia. Image credit Stuart Price for AU-UN IST via Flickr CC.

Early on November 12, retired Major Henry Smith called me from London to tell me that his former comrade and friend, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings had died. Rawlings lived many lives, transforming from idealistic young Air Force pilot to imprisoned coup-plotter to Chairman of two revolutionary military regimes, to champion of neoliberal reform and President of Ghana’s 4th Republic, before peacefully handing over power in 2001. I had gotten to know Rawlings over several years after he graciously allowed me to do a series of interviews for a book on 1980s politics. As news broke of his passing, I was disturbed to read the international coverage, which was riddled with factual errors and told a simplistic story of a stereotypic autocratic African military ruler.

The press did not reflect the fact that he was the transcendent African political figure of his generation. Rawlings���s story reveals the grand political transformations of the late 20th century and the ongoing significance of 1970s global geopolitics. He was one of the last radical 1970s heads of state, and one of the few who lived to old age and in his own country. Most revolutionaries of those era, died in exile or, like Maurice Bishop in Grenada and Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso, were killed as they challenged the West and experimented with new forms of governance.

As news of his sudden death spread in Ghanaian circles, it provoked a flood of memories of successes, violence, and traumas among key actors who supported and opposed him in shaping politics in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as among the general public. Continuing controversies around his legacy speak to his ongoing significance.

Rawlings, born in 1947, was of the generation that came of age around Ghana���s independence in 1957 and ongoing Cold War struggles, opposition to white rule in Southern Africa, the Algerian Revolution, and the Nigeria-Biafra civil war. He was part of Accra���s aspiring cosmopolitan scene, where young men and women blended counterculture and Black pride, highlife, soul, R&B, and Afrobeat music and the latest fashions with an anti-imperial sensibility. In this context, coups became so frequent around the continent that, as Chinua Achebe joked to me once, radio stations like the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation had established ritual protocols and set music for when rebel soldiers arrived to make overthrow proclamations. Uprisings could be vehicles for foreign manipulation or ways voiceless young critics of neocolonialism experimented with the promises of freedom.

In the late 1960s, Henry Smith, a young munitions officer and committed socialist had been instrumental in bringing Rawlings, a young Air Force fighter pilot, into the Free Africa Movement (FAM) organized by journalist turned infantry officer Major Kojo Boakye Djan. It was a clandestine group of young officers and intellectuals that discussed Marx, Mao, and Guevara and listened to LPs of Malcolm X speeches. The FAM had a long-term plan to lead a coup in 10 years, when the young officers would be in senior positions. Their aim was to spark a series of uprisings around Africa and realize Kwame Nkrumah���s vision of a politically-unified continent. Rawlings was particularly impassioned when he first read Frantz Fanon���s Wretched of the Earth through the group. He told me how he carried Fanon around for months and laughed remembering how he quoted long passages to whoever would listen.

As the Ghanaian economy stagnated in the mid-1970s, there were strikes, food and commodity shortages, hoarding, and black-market price hikes. Rawlings remembers growing resentment. ���People were hungry … Most officers could not see it, but I saw there was anger in the men���s eyes.��� Rawlings grew impatient. ���All Boakye Djan did was talk … he was never going to act,��� he recalled.

Rawlings began organizing his own alternative network, estimating that he tried 12 times to launch a coup. On May 15th 1979, he led a handful of Air Force men in what he explained to me was more an attempt to spark awareness of corruption and suffering than a strategic action. They were arrested after surrendering. At his subsequent public treason trial, prosecutors highlighted Rawlings���s concern with inequality and corruption. Newspaper and radio accounts quoted Rawlings as having said ���Leave my men alone��� when they were arrested. The media portrait of Rawlings as a self-sacrificial hero transformed him overnight into national celebrity.

Boakye Djan and Smith were angry that Rawlings had moved without them but rallied to fast-forward FAM���s timeline and break him out of jail. Before dawn on June 4, Air Force and 5th Battalion soldiers started an uprising in the barracks. Rawlings future changed at precisely 6am on June 4, 1979, when he gave an improvised speech live on the radio. He was breathless after running 500 meters to Ghana Broadcasting House. In those days, radio was the main medium of communication. That Monday, instead of the early morning news, Rawlings��� voice entered the houses, markets, and offices of the nation. ���The ranks have just gotten me out of my jail cell … They have taken over the destiny of the nation.��� Crucially, he did not say he was in charge of the country, as would be typical of a coup announcement, but rather proclaimed that the future was uncertain. He said that the rampaging soldiers were angry, ���full of malice that we have put into them��� and that a moral reckoning was coming. Radios crackled as he shouted into the microphone and banged his fist on the table. His voice sent shock waves. One teenager recalls listening from his family house. ���When I heard his voice that first time, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. We all ran outside to see what was happening.���

Rawlings did not know of the plan ahead of time. When the soldiers broke open his cell he recalls being uncertain if it was a government trick to kill him as he escaped. While he neither planned nor even fought in the insurrection, he was perfectly cast to play the hero who could unite a fractured public. He was a natural performer attuned to the power of spectacle. He was lean, muscular, and handsome and wore his neat Afro, scruffy beard, and aviator sunglasses with the hyper-masculine swagger of a film star. He was ���light-skinned,��� the progeny of a Gold Coast Anlo-Ewe mother and Scottish father which, in a post-independence racial-cultural logic, made him cosmopolitan to working people and enigmatic to more established families.

Rawling was made Chairman of the new Armed Forces Revolutionary Council. He pledged to maintain the schedule for upcoming democratic elections and the handover to a civilian government but first would oversee ���housecleaning��� exercises to purge the nation of indiscipline and corruption. However, Rawlings recalled the young officers were only tenuously in control. He said to me, ���We were riding the back of a tiger,��� as they struggled to contain violence they had released. As one student at the time told me, ���June 4th unleased the worst in Ghanaians. The violence was traumatic … but … people have to remember we were suffering and had nothing to lose … People who now do not want to admit it were calling for blood.��� On June 16 and June 26 the AFRC executed eight military leaders including three former heads of state by firing squad. Students and workers continued to march in the streets, calling for more sacrifices, chanting ���Let the blood flow!���

After three months, the AFRC handed over to the 3rd regime with a warning to the new president Dr. Hilla Limann that the soldiers would be watching. While most AFRC members were sent abroad, intellectuals in the New Democratic Movement (NDM) and young radicals in the June Fourth Movement (JFM) took up the revolutionary torch. Rawlings remained the most popular man in Ghana and, with the help of a new batch of radicals, plotted a return to power.

On December 31, 1981, Rawlings led another uprising to oust Limann. This time he intended to stay, announcing on radio ���Fellow citizens of Ghana … this is not a coup. I ask for nothing less than a revolution. Something that will transform the social and economic order of this country.���

Rawlings ruled as Chairman of the Provisional National Defense Council (PNDC). His charisma drew together a diverse, if brief, coalition of Marxists, unionists, workers, intellectuals, artists, law-and-order soldiers, and centrist civil servants aiming to restructure Ghanaian society.

The country was fractured and financially broke. Idealistic JFM leftists felt they had made possible Rawlings���s ���second coming��� and wanted to implement radical structural changes. They sought financial support from the Soviet bloc, though could not secure funds. Centrists and moderates, however, were concerned with imminent food, fuel, and medicine shortages.

Ghana���s radical turn was not unique but rather was part of a rebellious explosion around the world in 1979, as in Iran, Afghanistan, South Korea, Nicaragua, Grenada, and El Salvador conflicts exploded. This was perhaps the final moment when sustained radical critiques of capitalist geopolitics arose across the globe, only to be squashed in the coming years by the Reagan-Thatcher Cold War end-game that combined covert intervention and free market economic restructuring.

After intense debate, Rawlings supported Ghana���s acceptance of an IMF Structural Adjustment Program that mandated state privatization and opened the economy to international finance capital.

Leftists were furious. In their minds, they had brought Rawlings to power and he had betrayed them. Right-wing soldiers, conversely, bridled at the disrespect for military hierarchy and what they saw as Rawling���s illegitimate left-leaning leadership.

In June 1982, three high court judges and one retired officer were murdered. While a PNDC member was executed for the crime, for most people it has never been resolved and responsibility for the act still lay with Rawlings or his inner circle as the case seemed connected to questions around the legality of revolutionary activities.

For many this was a breaking point. Left factions were forced out or fled into exile. Moderates resigned. John Kufuor, who would be elected President in 2001, was an opposition member invited to join government. He explained to me that after the death of the judges he saw no way forward and resigned.

In London, Lome, and Lagos diverse cohorts of former Rawlings allies from leftist radicals to right-wing law-and-order soldiers created improbable alliances and, with foreign assistance, launched plots to oust Rawlings. The regime faced numerous coup-attempts and constant challenges to its legitimacy with from all sides. As one soldier who led a failed coup attempt and then fled into exile explained, at the time power was up for grabs and it was not clear whether Rawlings, or one of several other factions, would prevail.

Rawlings survived by meeting opposition with force and slowly rebuilding state security and stability. To his opponents, state violence was terrorizing and traumatic. As a revolutionary he had challenged the state���s monopoly on violence and claimed the moral right to defend the oppressed. Later, as the embodiment of the state, he fought to centralize power and legitimize his use of force against rival claims to authority.

He oversaw re-building the nation���s infrastructure and writing a new constitution. With the reestablishment of party politics, he founded the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and was elected first President of Ghana���s 4th Republic in 1993. In moving from populist military leader to civilian president he oversaw the building of a neoliberal service economy, the sale of state resources, and the proliferation of private media. He stepped down after two terms in 2001, becoming the first former military leader to win democratic elections then voluntarily leave power.

As Rawlings���s rule ended, the country struggled to understand his legacy.

I first met Rawlings in 1999 when I was working as a photographer at the torch-lighting ceremony for the 20th anniversary of the June 4, 1979 uprising. I observed as journalists chuckled at the middle-aged civilian President squeezing into his old Flight Lieutenant uniform as if he were trying to be two different people at once. He held Ghana���s factions together over 20 years because of his duality. His revolutionary, Pan-Africanist persona allowed Ghana to maintain a radical image while slowly building a secure centrist state oriented toward the global free-market. He stood at the nation���s crossroads, embodying the contradictory tendencies and moral polarities of a generation striving for a new future, while being pulled backwards and forwards. He was a savior to some and a devil to others.

J.J. was called ���Junior Jesus��� by masses of students, workers, and soldiers who saw him as a moral crusader, who understood their hunger and frustrations. They celebrated him for saving the nation from indiscipline, arguing that he had struggled to moderate the more violent elements of the revolution; and that he was ultimately a strategic pragmatist whose use of military discipline saved the country from catastrophic civil wars such as those in Liberia and Nigeria. Others called him ���Junior Judas,��� accusing him of betraying his supporters and setting the country backwards.

Relatives and intimates of those killed, detained, and tortured in various revolts have continued to hold Rawlings personally responsible for the deaths and for the destruction and vindictiveness of the soldiers. Children endured not only hearing in the press of their parents��� deaths but watched as their friends celebrated. In a nation where families are closely acquainted, this simmering trauma and anger burst into public and became a constant refrain after Rawlings stepped down and those in exile began to return to the country.

Rawlings had numerous circles of intimates and confidants in the military and politics. Many remained profoundly loyal to him. Others felt cast-off as new factions gained favor. Many soldiers who loyally followed him and did the bulk of the fighting, watched from the background as others benefiting from their sacrifices. Leftists and unionists instrumental in bringing him to power in both 1979 and 1981, felt he betrayed Pan-Africanism and socialism, and ended Ghana���s best chance to imagine a new post-imperial order. Marxist intellectuals bristled at Rawlings���s revolutionary public persona, arguing it was ironic because he in fact saved the nation���s bourgeoisie. The middle-class, for its part, saw him, not as fighting indiscipline, but as the instigator of violence who destroyed the nation���s civility just as it was stabilizing.

Rawlings��� political genius was his ability to read people and anticipate their moves. He could make anyone feel like the most important person in the room. He had a lifelong concern with alleviating the suffering of the nation���s and the continent���s most needy citizens. Many have pointed out he was a natural performer and intuitive improviser with the ability to draw the attention and loyalty of large and small audiences. Like all good politicians, Rawlings understood the importance of narrative, but over time, he wondered how his story would be told and what his long-term legacy would be. Playwright and PNDC Secretary Mohammed Ben Abdallah recalled that in the late 1980s, at the end of a meeting, Rawlings suddenly became introspective and asked no one in particular. ���Who will tell the stories of the revolution? …�� Who will talk to future generations about what we have accomplished?���

The first few times I interviewed Rawlings, I was so overwhelmed by his charisma, I could not properly ask questions. He was a great storyteller and rendered people���s desires, weaknesses, and character in a few brush strokes. He reveled in keeping his audience rapt. One time when he was telling me about eluding military intelligence, I leaned forward, taking notes furiously. He teased me that I was too interested in the story so he would save the ending for later. Several times, I arrived at his office expecting to stay for an hour and was there for seven hours and several meals. He could start on one topic detour by several decades for an hour before returning to the original topic. I eventually mustered the courage to ask difficult questions���about former allies turned enemies, and about the executions. He said that the real stories about Ghana���s past had been hidden for too long and the truth needed to come out for the nation to move forward. At the same time, he was awash in decades of struggles for power that entailed intense fights over how political history was understood. Rawlings was working on his own book and collecting stories, interviews, and materials from his past. When I asked to corroborate details about a particular coup and similar moments blurred together, he would call an old soldier to help him recollect or send me to meet with a former bodyguard, armored car driver, or security operative. I also sought out his allies, enemies, and former colleagues to collate multiple tales of Ghana���s political journey. The more people I spoke with the more contradictory versions of events I got. I struggled as a scholar to put together a singular story. I also began to realize that Rawlings���s political success stemmed from his performance skill and storytelling ability that maintained him at the center of the national narrative.

The last time I talked with Rawlings he was in a reflective mood. I had brought an MP3 of his coup announcement from June 4, 1979 and we sat in his office listening. He tilted his head back and tapped his hand to the rhythm of his younger self. In that moment of radical personal and national uncertainty he presented a vision of sovereignty in which ���You are either a part of the problem or a part of the solution there is no middle way ��� Natural leaders will now emerge not those imposed upon us.��� These utterances that launched him onto the national stage defined a landscape of power that the country navigated through subsequent decades. After playing the announcement a few times, I asked him if I could look at the old flight helmet he kept in a glass case near his desk. He took it out and held it with what seemed like both excitement and sadness.

As the revolutionary past grew increasingly distant for young Ghanaians, he lamented that sacrifices of the June 4th uprising and December 31st revolution had been wasted as the corruption and indiscipline that had caused so much anger back then were nothing compared to current levels of graft and inequality. It seemed that the burden of multiple past political battles weighed heavily on his shoulders. Rawlings was not someone to regret or apologize. But I think his way of taking responsibility for the violence of the revolutionary days was to remain strategically silent on some issues, even as he spoke at length. He had claimed responsibility for the actions of his men and for the nation when he declared the revolution. He understood that there was no way to respond to the anger and pain directed at him, but it was his burden to carry. He had more trouble accepting the silence of former allies who had sacrificed for the revolution and then felt betrayed.

Rawlings story provides lessons for a new generation of activists. He embodied the hopes and uncertainties of the 1970s generation as he guided Ghana across a complex, changing terrain. Ghana’s revolution promised liberation, but its legacy is traumatic and unresolved. Proponents lament its failures while opponents regret its destructiveness. As people reflect on Rawlings���s passing, stories from the past are coming up. Some are told in public, but most circulate in smaller networks and on social media. Multiple contradictory versions of what happened in revolutionary Ghana are starting to emerge. While some participants do not want to talk about the past, others embellish their roles. Some feel they have not had a chance to tell of their experiences. As stories of Ghana���s political past emerge, they tell of the hopes and dangers of struggling for radical freedom.

Rawlings was a man of passion who never stopped fighting for his people, especially the most vulnerable. Rest well.

Congo���s white ‘refugees’

Photo by Jordy MATABARO on Unsplash

This post is part of our series, ���Histories of Refuge,��� made up of essays from participants in the Rethinking Refuge Workshop. It is edited by historian Madina Thiam.

Not all people seeking refuge in Africa have been black. In a forthcoming article for this series, Alfred Tembo and Jochen Lingelbach write about Polish World War II refugees who sought safety in British colonial Africa. Another group of white refuge-seekers in Africa consists of whites who fled from their African countries of residence after the fall of colonial and white minority rule. Their history is connected to the idea of racial solidarity among Africa���s white societies.

Algeria, Angola, and Mozambique���s independence all resulted in the rapid departure of the majority of their white inhabitants. We can trace the origins of this broader phenomenon to the decolonization of Belgian Congo (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo). Five days after Congo���s independence celebrations on June 30, 1960, widespread panic set in among its white population when African members of the Congolese army started a mutiny. The frustration and anger of the African soldiers were rooted in the racial violence and structural racism that had defined colonial Congo (1885-1960). Much of the violence by the mutineers was directed toward the white community, resulting in the hasty departure of most white residents from the newly independent African state.

Thousands of whites crossed the border into neighboring territories like Sudan and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) seeking refuge. The different colonial and white minority regimes across Africa immediately put initiatives in place to receive and provide for incoming refuge-seekers, while their white communities made extraordinary efforts to accommodate fellow whites. Refuge-seekers were housed, clothed, and fed, as well as assisted with repatriation back to their country of nationality. The notion of racial solidarity shaped this noteworthy reaction by white societies across Africa.

Africa���s different white societies typically did not share strong daily social connections with one another. Additionally, each society was further divided along ethnic and class lines, forming their own separate communities. Yet, all of these communities and societies shared the unique identity of being a white minority in Africa���privileged and dominant over the black population. Whenever a white minority group was perceived to be threatened by the black majority, a display of solidarity based on their shared identity emerged. These different white communities considered the adversity experienced by Congo���s white refuge-seekers as an attack on the entire group. What happened to Congo���s white population became symbolic of deep-seated white anxieties about decolonization and majority rule.

Although white minority societies in Congo-Brazzaville (Republic of Congo), Kenya, or Angola all undertook action to receive refuge-seekers, the case of apartheid South Africa stands out. What made South Africa unique was that it actively encouraged white-refuge-seekers from Congo to come to South Africa and permanently settle there. The apartheid government went to great lengths to assist Congo���s refuge-seekers, paying for their journey to, and stay in, South Africa, and going as far as organizing employment for them. By the end of 1960, about 2,342 refuge-seekers from Congo had crossed the South African border.

Despite racial solidarity being the driving force that made white South Africa come to the aid of these white refuge-seekers, it was less selfless and united than it first appears. Although the South African government and the local white press expressed enthusiasm, the white public���s support was neither overwhelming nor unlimited. On several occasions, Pretoria had to spur on citizens to donate money and food after an initially muted response. The enthusiasm of those South Africans who responded to the clarion call also quickly diminished, as homeowners became tired of housing refuge-seekers and the organizations whose spaces were transformed into refugee centers wanted them returned.

Pretoria���s efforts to assist refuge-seekers from Congo was not based entirely on humanitarian principles. The South African government���s desire to bolster the country���s white population, which was shrinking percentage-wise, was an important motivation. Although Pretoria was eager to attract white refuge-seekers from Congo, the right pedigree was important. As in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Southern European refuge-seekers from Congo were generally considered undesirable. Western Europeans, who understood the concept of maintaining white prestige and did not need to adapt to apartheid, were preferred.

In turn, a questionable sense of white camaraderie was present among Congo���s refuge-seekers. Reports of refuge-seekers abusing the South African relief system to further their own mobility were common. Belgian refuge-seekers in South Africa, for instance, grossly abused the credit system that had been set up especially for them, leaving behind large amounts of debt when leaving South Africa back to Belgium or Congo.

The white exodus that followed Congo���s independence on June 30, 1960 thus resulted in an intense moment of racial solidarity amongst Africa���s white minority societies. Apartheid South Africa���s reaction to Congo���s white refuge-seekers presents us with a valuable episode in the history of refugees in Africa. Besides disrupting existing racial stereotypes about refuge seeking in Africa, it highlights the importance, complexity, and limitations that solidarity plays in aiding those seeking refuge.

Congo���s white refugees

Photo by Jordy MATABARO on Unsplash

This post is part of our series, ���Histories of Refuge,��� made up of essays from participants in the Rethinking Refuge Workshop. It is edited by historian Madina Thiam.

Not all people seeking refuge in Africa have been black. In a forthcoming article for this series, Alfred Tembo and Jochen Lingelbach write about Polish World War II refugees, who sought safety in South Africa. Another group of white refuge-seekers in Africa consists of whites who fled from their African countries of residence after the fall of colonial and white minority rule. Their history is connected to the idea of racial solidarity among Africa���s white societies.

Algeria, Angola, and Mozambique���s independence all resulted in the rapid departure of the majority of their white inhabitants. We can trace the origins of this broader phenomenon to the decolonization of Belgian Congo (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo). Five days after Congo���s independence celebrations on June 30, 1960, widespread panic set in among its white population when African members of the Congolese army started a mutiny. The frustration and anger of the African soldiers were rooted in the racial violence and structural racism that had defined colonial Congo (1885-1960). Much of the violence by the mutineers was directed toward the white community, resulting in the hasty departure of most white residents from the newly independent African state.

Thousands of whites crossed the border into neighboring territories of Sudan and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) seeking refuge. The different colonial and white minority regimes across Africa immediately put initiatives in place to receive and provide for incoming refuge-seekers, while their white communities made extraordinary efforts to accommodate fellow whites. Refuge-seekers were housed, clothed, and fed, as well as assisted with repatriation back to their country of nationality. The notion of racial solidarity shaped this noteworthy reaction by white societies across Africa.

Africa���s different white societies typically did not share strong daily social connections with one another. Additionally, each society was further divided along ethnic and class lines, forming their own separate communities. Yet, all of these communities and societies shared the unique identity of being a white minority in Africa���privileged and dominant over the black population. Whenever a white minority group was perceived to be threatened by the black majority, a display of solidarity based on their shared identity emerged. These different white communities considered the adversity experienced by Congo���s white refuge-seekers as an attack on the entire group. What happened to Congo���s white population became symbolic of deep-seated white anxieties about decolonization and black majority rule.

Although white minority societies in Congo-Brazzaville (Republic of Congo), Kenya, or Angola all undertook action to receive refuge-seekers, the case of apartheid South Africa stands out. What made South Africa unique was that it actively encouraged white-refuge-seekers from Congo to come to South Africa and permanently settle there. The apartheid government went to great lengths to assist Congo���s refuge-seekers, paying for their journey to, and stay in, South Africa, and going as far as organizing employment for them. By the end of 1960, about 2,342 refuge-seekers from Congo had crossed the South African border.

Despite racial solidarity being the driving force that made white South Africa come to the aid of these white refuge-seekers, it was less selfless and united than it first appears. Although the South African government and the local white press expressed enthusiasm, the white public���s support was neither overwhelming nor unlimited. On several occasions, Pretoria had to spur on citizens to donate money and food after an initially muted response. The enthusiasm of those South Africans who responded to the clarion call also quickly diminished, as homeowners became tired of housing refuge-seekers and the organizations whose spaces were transformed into refugee centers wanted them returned.

Pretoria���s efforts to assist refuge-seekers from Congo was not based entirely on humanitarian principles. The South African government���s desire to bolster the country���s white population, which was shrinking percentage-wise, was an important motivation. Although Pretoria was eager to attract white refuge-seekers from Congo, the right pedigree was important. As in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Southern European refuge-seekers from Congo were generally considered undesirable. Western Europeans, who understood the concept of maintaining white prestige and did not need to adapt to apartheid, were preferred.

In turn, a questionable sense of white camaraderie was present among Congo���s refuge-seekers. Reports of refuge-seekers abusing the South African relief system to further their own mobility were common. Belgian refuge-seekers in South Africa, for instance, grossly abused the existing credit system, leaving behind large amounts of debt when leaving South Africa back to Belgium or Congo.

The white exodus that followed Congo���s independence on June 30, 1960 thus resulted in an intense moment of racial solidarity amongst Africa���s white minority societies. Apartheid South Africa���s reaction to Congo���s white refuge-seekers presents us with a valuable episode in the history of refugees in Africa. Besides disrupting existing racial stereotypes about refuge seeking in Africa, it highlights the importance, complexity, and limitations that solidarity plays in aiding those seeking refuge.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers