Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 4

August 4, 2024

The Boos brothers of cafeterialand

It was an orphaned family that had gone through some difficult times that developed one of the early, very successful chains of cafeterias in California.

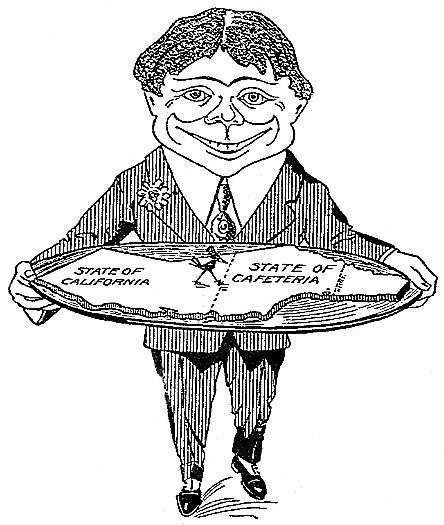

The chain of Boos Brothers cafeterias was one of the first in Los Angeles, contributing to the flood of cafeterias that soon appeared in that city and elsewhere in Southern California. Californians to the north ridiculed the trend, referring to Los Angeles and southern California as the “State of Cafeteria.” It’s true, of course, that cafeterias have never been seen as fashionable and sophisticated.

The Boos [probably pronounced Boes] family story reads like a fictional tale. The Moscow, Ohio, family of nine children were orphaned when both parents died in the late 1880s, followed by the eldest son’s demise two years later. That left Horace, about 19, as caretaker of his three brothers and four sisters. In his will, their father had expressed a wish that they all stay together, live in the family home, and be self supporting. They followed his wishes except for staying in their small hometown. At some point Horace moved the family to Cincinnati where he got a job as a typesetter for the Cincinnati Enquirer. He and his brothers, and at least one sister, also operated a grocery story, then a hotel and restaurant in Cincinnati.

Before the brothers, and some of the sisters, moved to California in 1906 they had also lived briefly in Rochester, New York City, and St. Louis, operating restaurants in all of them, including a lunchroom at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

Once in California they acquired a ranch in San Gabriel, offering eggs for sale in a 1906 advertisement. By August of that year they had opened their first cafeteria in Los Angeles. They also continued to operate the ranch, supplying their restaurants with eggs into the 1920s.

By 1909 they had expanded to three cafeterias. Judging from postcards like the one here, the early cafeterias may have been exceptionally sanitary and well outfitted but had a somewhat functional appearance. Gradually their cafeterias became more decorative, particularly when they moved into buildings they had built.

In 1922 they opened a newly built cafeteria at 618 S. Olive decorated in what they described as Spanish and Moorish style. An advertisement celebrated its interior: “Accentuating the impressive spaciousness of the place, are three arched windows of great height in the north wall. In corresponding positions in the south wall, equivalent in number and size, are mural paintings of exquisite technique, depicting with historical exactness, Cortez before Montezuma.”

The newest, and last, cafeteria, built at 530 S. Hill in 1926 — a location previously occupied by a failed B&M Cafeteria — was custom-built and featured the largest orchestra, one of 9 pieces. It also was fitted with rest rooms filled with upholstered arm chairs and settees. A row of water fountains referred to as a “Persian fountain” was backed by a large and impressive scene painted on tiles [shown here].

In 1927 the cafeteria company celebrated its 20th anniversary, publishing a booklet called “Glancing Back Along the Cafeteria Trail.” At that point the business operated six cafeterias in Los Angeles and one on the island of Catalina opened in 1918.

The booklet celebrated their success and gave some idea of what it took, such as purchasing 870,000 pounds of beef per year and 40,800 chickens. An estimate of how many acres it would take to grow the fruits and vegetables used by the chain came to 20,000. The Boos used only fresh vegetables, nothing canned. All but one of their locations had live orchestral music.

Surprisingly, the year after the celebratory booklet was published, the brothers sold the chain to the Childs corporation, including all six cafeterias in Los Angeles and the one on Catalina Island. At that point the six L.A. cafeterias were reputedly serving 10M meals a year. The sale to Childs, which kept the Boos name, was said to net $8M for the three remaining brothers. Horace Boos had died the previous year and it’s possible that might have motivated the sale.

In the Depression, Childs sold their Boos holdings, two going to Clifford Clinton of Clifton’s Cafeterias fame, and two returning to the Boos brothers, according to some accounts. Other reports, confusingly, had the brothers buying back all the cafeterias. Whichever was the case, the only one that seemed to reopen under the control of the Boos brothers was the cafeteria at 530 S. Hill. During the Depression it met the needs of people with little money, offering low-priced dishes such as soup and spaghetti for 8 cents and most vegetables for 7 cents.

The S. Hill Boos Brothers cafeteria was still in business as late as 1955, advertising in the Los Angeles Times as “The Original.” But at some point it acquired a new owner doing business as Green’s Cafeteria. In 1960 Green’s was out of business and the equipment was auctioned.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

July 23, 2024

In the kitchen at Sardi’s

To gather recipes for the Sardi’s cookbook Curtain Up at Sardi’s [1957], co-author Helen Bryson spent two and half weeks, six days each week, in Sardi’s restaurant kitchen. She asked a lot of questions about the food preparation. It was the only way to put together a cookbook, something that she said had never been done before in the restaurant’s long history that dated back to the 1920s. [The restaurant pictured above in the 1950s; below is a 1924 advertisement — “Your Restaurant” is aimed at theater people]

The recipes were intended for use by the public. Whether the restaurant’s chefs ever looked at them is another question. Of course the book’s recipes were adapted for smaller amounts than were normal for the restaurant, and they were no doubt simplified for home cooks too.

And yet the book also includes 26 sauces and dressings, some of them classic French sauces that are far from simple. “Sardi Sauce,” for instance, is made with Sherry wine, light cream, and whipped cream, but also includes Velouté Sauce and Hollandaise Sauce. Velouté Sauce is made with chicken stock and roux (chicken fat and flour). The book also includes a much simpler version, perhaps designed for the homemaker, called Emergency Velouté Sauce (butter, flour, canned broth, and bay leaf).

Later, in contrast to the intricacies of sauce making, comes an amazingly simple recipe for Spaghetti with Tomato Sauce en Chafing Dish which calls for spaghetti, boiling water, salt, tomato sauce (can be canned!) and grated Parmesan. The cook could instead choose to make the book’s Tomato Sauce, but that, by contrast, calls for 11 ingredients including a ham bone. Using that sauce the spaghetti might qualify for a chafing dish but otherwise, I think not.

Mid-century dishes at Sardi’s covered a wide range of cuisines. Italian and French were in the lead, as were favorites of indeterminate origin such as Supreme of Chicken à la Sardi ($1.50 in 1939). But the book also includes hot tamales with chili con carne and turkey chow mein, and even makes room for a few “low-calorie plates,” which were becoming popular in the 1950s.

The recipe for Supreme of Chicken à la Sardi is as follows — minus recipes for the accompanying Duchesse Potatoes and Sardi Sauce. Together, those two components add a major amount of cream to this mid-century “specialty of the house.”

1 cup Duchesse Potatoes

6 slices cooked breast of chicken, heated in sherry wine

12 stalks green-tipped asparagus, canned or cooked

1 cup Sardi Sauce

2 teaspoons grated Parmesan cheese

After being assembled on a serving dish, with the chicken resting on the asparagus, surrounded by piped potatoes and all covered with Sardi Sauce and Parmesan, the dish was to be browned lightly under the broiler.

Though Sardi’s food was considered good, the restaurant was not among those that won awards for their cuisine. It is rarely mentioned in “best food” books and articles. Rather, the restaurant’s fame derived from its role as a haven for theatrical people of every kind – actors, agents, producers, publicists, and devoted patrons of live theater. In the early days, Vincent and Eugenia Sardi won over theater people by extending credit to those down on their luck. To the wider public it was most attractive as a site for celebrity spotting and autograph collecting. The restaurant was also well known for years for its canny hat check “girl.”

In the 1963 movie Critic’s Choice Bob Hope plays a critic whose wife, played by Lucille Ball, writes a play which he will need to review. Since it isn’t very good, an honest review would threaten his marriage. [Lucille Ball does not appear in the Sardi’s scene shown above.]

Like the Brown Derby in Los Angeles and the London Chop House in Detroit, Sardi’s decorated its walls with portraits of its celebrity guests – and still does. Some of the older drawings, from the 1920s through the 1950s, have been saved and can be seen by appointment at the NY Public Library.

Until 1947, when Vincent and Eugenia (“Jenny”) Sardi retired and sold the restaurant to their son, Vincent Jr., they divided duties, with Vincent in the dining room greeting guests and Jenny looking over the kitchen and doing the buying. According to one account she was the beloved member of the couple, attracting theatrical guests to the kitchen to visit with her, while Vincent did his duty greeting guests wearing his “guest smile.” A profile in 1939 referred to him as a “chilly individual.” He did, however, give his wife credit for her role in the restaurant’s success. “She does it all,” he said in one interview. [above: the Sardi’s in 1939]

Despite some rocky years and changes in ownership, Sardi’s restaurant, still decorated with celeb faces, continues in business today on W. 44th Street.

A final note: in case anyone was wondering, Sardi’s in New York had no connection with the restaurant of the same name in Los Angeles that opened in the 1930s clearly modeled on the original – a situation that vexed the Sardis.

And thanks to the kind reader who sent me a copy of Curtain Up.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

July 4, 2024

Happy birthday to a salad?

This morning I heard a story on the radio about Caesar salad that claimed today was the salad’s 100th birthday.

I can understand that it becomes difficult to come up with holiday stories that are novel and of general interest. But I have my doubts about the accuracy of that anniversary date.

Still, I will take advantage of it to recommend a story about Caesar salad that I wrote in 2019, at a time when my blog was fairly new and had fewer readers.

Meanwhile, have a great holiday!

June 23, 2024

Behind the scenes at Gonfarone’s

There is nothing as interesting (to me) as a memoir about a restaurant from an insider who reveals its workings not usually known to customers. Papa’s Table d’Hôte by Maria Sermolino is such a memoir, published in 1952, decades after her father’s ownership of the New York City restaurant, Gonfarone’s.

Maria’s career as an editor and writer was extensive. After graduating from the Columbia School of Journalism and spending a couple of years writing about post-WWI conditions in France, she interviewed Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Later she worked for Time, was the editor of The Delineator and for 11 years an associate editor for Life magazine. She attributed her lifelong unmarried status to overhearing conversations about women among waiters and from male guests invited by her father to join him at his table. [above, Maria at age 25, in 1920, the year she interviewed Mussolini]

Gonfarone’s began in business around the turn of the last century as an Italian pension-type eating place, transitioning into a bohemian resort for Greenwich Villagers. It was run initially by Caterina Gonfarone who operated it in a basement on the corner of Eighth and McDougall streets. She soon partnered with Maria Sermolino’s father, Anacleto, who saw to it that the dining room was moved upstairs. Then, as neighboring residences were acquired by the partners, the popular Latin Quarter table d’hôte expanded to eventually accommodate 500 diners at a time. Sermolino soon acquired the restaurant from Madama Gonfarone, but kept her name.

After the Sermolino family moved into the complex of buildings (which also included a small hotel), Maria spent much of her childhood in the restaurant. Chapter 6 of her book is entitled “The Barroom Was My Playground.” She assisted her mother, the restaurant’s cashier, by spotting waiters who failed to pay her mother for drinks they ordered for customers at the bar. (They would have been reimbursed later, but without paying first they were able to keep the customers’ payments for themselves.)

But that is not the only way in which the staff tried to make extra money on the side. Dishwashers sold food scraps and fat to a company that made soap, with higher prices paid for barrels with more fat. On occasion Madama Gonfarone would catch a dishwasher pouring a large tin of unused lard into a barrel for a higher payoff. It was also common for the staff to smuggle out bottles of wine, chickens, lobsters, and other choice food items when they left at night. Her father refused to institute routine searches because he thought it would be bad for morale.

Because the restaurant was connected to a hotel, the bartender also acted as the room clerk. He took advantage of his position by renting rooms to prostitutes, even on occasion — when she was away — renting Madama’s room for more than double his usual charge.

Not all the restaurant’s customers were treated equally. Waiters would see to it that their favored regulars got larger portions, choicer cuts of meat, and less melted ice in their drinks. A standard menu, 50 cents on weeknights and 10 cents more on Saturdays and Sundays, featured Antipasto, Minestrone, Spaghetti, Salmon with Caper Sauce, a Sweetbread, Broiled Chicken or Roast Beef, Vegetables, Potatoes, Green Salad, Biscuit Tortoni or Spumoni, Fresh Fruit, Assorted Cheeses, and a Demi-tasse. In all likelihood the portions would have usually been on the small size.

“By the simple act of ordering spaghetti an American was plunged into a foreign experience,” observes Sermolino. [above, 1916 advertisement from The Greenwich Village Quill; below, 1919 Quill]

All meals came with a glass of California claret, which the restaurant bought 40 or 50 barrels at a time, reducing their cost to ten cents a gallon. Apart from that free glass, which impressed many American patrons who were unfamiliar with wine and considered it exotic, the bar was a money maker. Maria called it “a gold mine.” A Manhattan cocktail — with cherry — cost 3 cents but sold for 15 cents, she explained.

Banquet menus were grander and supplied more alcoholic beverages, as is shown in a 1904 menu above for a dinner given to honor a supporter of Democrats in the Tammany-controlled area occupied by the restaurant.

The restaurant’s best years were before World War I, when it was not unusual to serve four to five thousand dinners on an average weekday and double that on a good Saturday or Sunday, with waiting patrons spilling down the hall and into Macdougal Street. When food ran low the cooks would water the soup and waiters would offer patrons omelets.

With the onset of Prohibition, Maria’s father decided to get out of the business and concentrate on his other interest, real estate. Under new ownership, Gonfarone’s remained open for another 10 years, until 1930. The buildings were razed in 1937.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

June 9, 2024

Playboy on the town, 1850s style

Quite by accident I discovered a book called Fresh Leaves from the Diary of a Broadway Dandy, a moral tract that conceals its true purpose by enticing the reader with details from the wild life of a roguish playboy in New York city. It was published in 1852. [Except for one Thompson’s advertisement, also from 1852, the images in this blog are from the book.]

The book was promoted with the headline “Rich and Racy.” Author John D. Vose, who had earlier been the editor of a humor publication called The New York Picayune, wrote a few other short “diaries,” one titled Seven Nights in Gotham, another called Yale College Scrapes, and a third, Ten Years on the Town. Alas, I could not find those.

The Diary of a Broadway Dandy describes the doings of one particular young man named Harry for whom money flows endlessly. At one point he enumerates some of the 30 bills he just received from fashionable eating and drinking spots around town, all of which amount to a considerable sum which he dismisses as insignificant.

In an average week, he and his pals spend most of their time drinking uncountable bottles of booze of every kind, destroying property by breaking furniture, mirrors, and other things, and arriving back at their abodes extremely late in a drunken state. The dandies also pursue women, but just how far that goes is not detailed.

When Harry’s parents try to get him to go straight, attend church, and get a job on Wall Street, he balks and moves into a hotel. Clearly he belongs to a set of men identified in an advertisement for Charley Abel’s place on Broadway in 1852 as “the wits, fast men, and bloods of the town.”

His favorite eating and drinking places were plentiful, and included many on Broadway, among them The Arbour, Shelley’s Restaurant and Oyster Saloon, Taylor’s, and Thompson’s. (Note that at that time “saloon” meant a large roomy space, not necessarily a barroom.)

Of course, being a member of the “bon ton,” he also patronized Delmonico’s, taking his pals there for dinner one evening. He clearly liked to play the generous host not concerned about cost, but things didn’t go just as he planned this time. The day before he had ordered a dinner costing precisely $50 (about $2,000 today). When the bill came it was only for $42 and that made him quite angry. Next, he ordered a slice of white bread. Then, to make the point that he expected his exact demands to be met, he buttered the bread, placed a $50 bill on it, and ate it all.

At other places he and his friends visited, they drank vast amounts of booze and left behind a trail of destruction. On one occasion, on which nine bottles of champagne were consumed, then some brandy to settle their stomachs, he described the following:

"By some unknown way, a large mirror got cracked; but, as the landlord was a clever man, and I didn’t want to have no fuss, it being Sunday, I at once settled the loss with seven ten dollar bills, as I was not confident whether I did throw a champagne bottle against it or not. It has rather run in my mind since, that I did, but I won’t be certain. Yes, several chairs got broken, and were minus of legs and backs, yet that was laid to unknownity."Other casualties of drinking bouts at various times included damage to himself such as losing the heel of his patent leather shoes, staining his white pants, breaking his gold watch chain and his watch crystal, and breaking a bottle of champagne. He dismissed them, and he didn’t sound terribly contrite about an accident that happened on a Sunday either:

"Sloped from home, and took a drive with a particular friend out to the ‘Abbey.’ Found a great number out there. Our team being very dashy, attracted attention from every quarter – especially of the ladies. We drank twice, order a waiter to brush our attire three different times – made five new acquaintances, and then returned home. On our return we run the tire off of one hind wheel, causing four spokes to fall to theground. So much for not being at church!"By the end of the book, after the reader has enjoyed delving into the seamy exploits of the rich, the author issues stern criticisms. He concludes that it isn’t enough for a young man in New York who wants to be seen as an elite to have “the rocks,” go to the right places, or dress fashionably. Along with the rules of being a gentleman, “He must know how to be the part of a knave, a rascal,” . . . cultivating deceit “between the two gateways of virtue and vice, by sun-light and by gas-light.” Why? Because “This is a very wicked city.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

May 26, 2024

Finds of the day

Slim pickings for a restaurant ephemera collector at the giant Brimfield flea market recently, but at least I turned up a few finds. Among them were two small menus and a business card, all from eating places run mainly by women. The size of the two menus makes me wonder if male-owned restaurants ever employed any this tiny.

The Henniker Tea Room

The oldest of the three finds was a menu from The Henniker Tea Room in 1932. It took me a while to realize that its location “Midway between Westfield and Brocton” put it in New York state.

I discovered that it is a relic of hard times in a double sense. The front of the menu says “Tenth Season,” so it was begun in 1922. That was the year that the owner’s husband, a superintendent of schools, died of tuberculosis, which probably meant that she had to earn a living for herself and her two daughters.

The second hardship associated with this menu is that it dated from the depths of the Depression. I suspect that is the reason she stopped charging an extra 15 cents for salad with Sunday dinner specials, and reduced the price of potato salad from 30 to 25 cents.

Possibly the tea room failed in the Depression because by 1940 Frances Swain was living in a lodging house and working as a secretary for the YMCA. But her fortunes must have improved after that because in 1950, at age 66, she had become director of the YMCA and headed her own household with additional income from three roomers.

The Salmagundi

The Salmagundi was a seasonal tea room that probably opened in the late 1920s. It was located on Beacon Street in Boston, in a rooming house that the married couple who operated it lived in. I’m guessing the menu shown here is from the early 1950s, an era when tomato juice appetizers were still popular.

The word salmagundi was an old-fashioned but rather artsy word. It could apply to many kinds of mixtures, whether art, collections of short stories or poems, or a multi-ingredient salad.

The Salmagundi was a frequent meeting place for women’s clubs, bridal showers, business and professional groups, and gatherings of college alums.

Duncan Hines, in the 1946 edition of Adventures in Good Eating, declared The Salmagundi “One of the most popular places in Boston,” and praised its “unusual food combinations, delicious hot breads, and good desserts.”

A student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology took his girlfriend to dinner there in 1950. He said it was a quiet place with three small dining rooms and a limited menu but one he approved of since it included lobster, steak, and chicken. They ordered duck and found it delicious, and liked the “fancy rolls.” But the check totaled a bit over five dollars, so he had to borrow some money from his “chick.”

Around 1960 it passed into new hands, and the owner tried to get a license to serve wines and malt beverages. I found no trace of it after 1962.

Mary Hartigan Restaurant

Although Mary Hartigan’s business card is the smallest of the day’s finds, I discovered that hers was the most successful business of the three. She established it in 1933 in what was formerly a Dutchland Farms that she had run. [above, front and back of business card]

The Dutchland Farms chain in New England, beginning as dairy stores, developed into restaurants quite similar to Howard Johnson’s shortly before the chain failed in the Depression. Some were converted to Howard Johnson’s, but Mary Hartigan, who also ran one in Harwich Port MA, decided to run her Dedham place independently under her own name.

Nevertheless Mary Hartigan’s and Howard Johnson’s shared a similar appearance as well as a similar menu. A Hartigan menu from 1952 shows that she kept the strong link to dairy products in her new restaurant, dedicating an entire page to ice cream concoctions such as sodas, sundaes, freezes, frappes, floats, and malted milk. In addition to the standard steak and chicken entrees, the menu also presented a variety of seafood, including seafood plates, baked lobster, Cape scallops, broiled swordfish, and fried clams. Tomato, grapefruit, and pineapple juice served as appetizers.

1952 was also the year that the restaurant acquired a liquor license. In 1959 the building was enlarged and remodeled. [above, business card interior]

When Mary Hartigan died suddenly in 1961 her obituary in the Boston Globe observed that the restaurant was “one of the best known in the state.” She left it to a niece who ran the business until 1970 when it was sold to a new owner who said he planned to keep the staff, some of whom had worked there for three decades.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

May 12, 2024

The ‘bohemian’ restaurant in fiction

There was a time when many Americans considered inexpensive French or Italian restaurants naturally bohemian – wild and crazy, not too clean, filled with oddball characters, and offering menus of unfamiliar and dubious dishes. But nonetheless fascinating. Novelists liked to use them as settings, so they turned up in fiction of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the excerpts below illustrate.

In the final sample presented here we meet up with a restaurant keeper who wishes his place was more bohemian because that would make it a better draw.

1886 The Midge, Henry C. Bunner – To celebrate the Midge’s 16th birthday, her guardian, a doctor, takes her out to dinner at a table d’hote in New York City’s French quarter.

It was a modest feast, only a plain table-d’hôte dinner, eaten in the heart of the quarter, at a cost of half-a-dollar apiece. They had tried more elaborate dinners, at the great hotels up-town; but they preferred the simpler joys of Charlemagne’s restaurant. They both possessed that element of Bohemianism which belongs to all good fellows; the Midge was a good fellow, as well as the Doctor.

Charlemagne’s is a thing of the past; but he was a jolly king of cheap eating-house keepers while he lasted. He gave a grand and wholesome dinner for fifty cents. The first items were the pot-au-feu and bouilli. If the pot-au-feu was thin, the bouilli was so much the richer. And if the bouilli was something woodeny, why, you had had all the better pot-au-feu before it. Then came an entrée, calves’ brains, perhaps, or the like; a rôti, a vegetable or so coming with it; a good salad, chicory or lettuce or plantain, a dessert of timely fruits, a choice of excellent cheese, and a cup of honest black coffee. And with all this you got bread ad libitum and a half bottle of drinkable wine, that had never paid duty, for it came from California, though it called itself Bordeaux.

1896 Some Modern Heretics: A Novel, Cora Maynard – About two women who adventurously move to Boston to live in a flat and do their own housework. But they don’t know how to cook.

And the alternative of tramping out to restaurants at all hours was a Bohemianism which, in spite of her late advancement, she could not contemplate serenely. It appeared positively disreputable. If her father knew of the actual circumstances of her situation a prompt withdrawal of his original consent would have cut short Vida’s visit on the spot; but she left him in tranquil ignorance . . .

By seven o’clock the girls realized that it was time to have dinner, and then came Vida’s great trial. It was too late to think of cooking anything themselves, so there was nothing to do but face the restaurant.

“Isn’t it a very – a very queer thing to do?” Vida ventured feebly. She would much rather have bought some crackers and eaten them at home in their unpalatable dryness.

“Why, no. It’s a little quiet place we’re going to. I’ve often been. You know we girls don’t believe in being restricted by senseless prejudices. Good gracious, one can’t be so dreadfully hampered in these days of rationality!”

Before long Vida got used to the restaurant, and even enjoyed it when they felt too tired or too lazy to struggle with the cookbook. She enjoyed the whole queer situation and got a taste of such freedom as she had never before dreamed of.

1910 Predestined, Stephen French Whitman – Featuring Benedetto’s, a favorite with artists in New York City.

On the north side of Eighth Street, close to Washington Square, an old, white dwelling-house had been converted into an Italian restaurant, called “Benedetto’s,” where a table d’hôte dinner was served for sixty cents. Some brown-stone steps, flanked by a pair of iron lanterns, gave entrance to a narrow corridor. There, to the right, immediately appeared the dining-room, extending through the house — linoleum underfoot, hat-racks and buffets of oak aligned against the brownish walls, and, everywhere, little tables, each covered with a scanty cloth, set close together.

Felix, at the most inconspicuous table, consumed a soup redeemed from tastelessness by grated parmesan, a sliver of fish and four slices of cucumber, spaghetti, a chicken leg, two cubic inches of ice cream, a fragment of roquefort cheese, and coffee in a small, evidently indestructible cup. Then, through tobacco smoke, he watched the patrons round him, their feet twisted behind chair-legs, their elbows on the table, all arguing with gesticulations. Sometimes, there floated to him such phrases as: “bad color scheme!” “sophomoric treatment!” “miserable drawing!” “no atmosphere!” Benedetto’s was a Bohemian resort.

1912 The Soul of a Tenor, W. J. Henderson – According to a review, “The reader is taken behind the scenes at performances and rehearsals and into the dressing rooms and boudoirs of the artistes; into the café, where foreign singers congregate.”

As for those women who figure in all animated chronicles of the present kind, some of them may have had husbands, but they have tried to forget them, and usually with success. Little Italian restaurants, with hot and opaque atmospheres, are in accord with their temperaments, for their part of the opera world is hot and opaque at all seasons of the year.

It was not a pretty place, that particular Italian restaurant. All the men in it seemed to require cigarette smoke as a condiment for food, and they chewed and puffed alternately. The room was filled with a wreathing blue fog, through which strange head-dresses and still stranger gowns could be seen, for the denizens of this world always garb themselves in streamers of splendor and look not unlike perambulating lamp shades.

They were not only singers. Some were impecunious painters and some were patrons of the arts, who were wont to shout “bravo” from the highest seats in the temple. It gave them a fine satisfaction to eat within reach of real singers. And they were not all Italians, for one feast of spaghetti makes the whole world of Bohemia kin.

1914 Our Mr. Wrenn; The Romantic Adventures of a Gentle Man, Sinclair Lewis – Mr. Wrenn is a lonely lodger who timidly invites a neighbor, Theresa Zapp, to dinner at a restaurant run by Papa Gouroff. She is described as “forward” and “gold-digging.” Although she is not interested in Mr. Wrenn, she accepts his invitation, but fails to be impressed by the restaurant.

The Armenian restaurant is peculiar, for it has foreign food at low prices, and is below Thirtieth Street, yet it has not become Bohemian. Consequently it has no bad music and no crowd of persons from Missouri whose women risk salvation for an evening by smoking cigarettes. Here prosperous Oriental merchants, of mild natures and bandit faces, drink semi-liquid Turkish coffee and discuss rugs and revolutions.

In fact, the place seemed so unartificial that Theresa . . . was bored. And the menu was foreign without being Society viands. It suggested rats’ tails and birds’ nests, she was quite sure. She would gladly have experimented with pate de foie gras or alligator-pears, but what social prestige was there to be gained at the factory by remarking that she “always did like pahklava”?

Papa Gouroff was a Russian Jew who had been a police spy in Poland and a hotel proprietor in Mogador, where he called himself Turkish and married a renegade Armenian. . . . He hoped that the place would degenerate into a Bohemian restaurant where liberal clergymen would think they were slumming, and barbers would think they were entering society, so he always wore a fez and talked bad Arabic. He was local color, atmosphere, Bohemian flavor.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

April 28, 2024

California coffee shops

With the end of World War II, the United States became the undisputed world power as well as the leading economy, producing the largest share of the world’s goods.

Many changes took place in American society as the soldiers returned. Suburbs sprang up with housing for growing families, shopping centers appeared, and many workers enjoyed prosperity. And a new type of eating place came into being, known as the “California coffee shop.” There had been coffee shops before that, but Southern California introduced new features, particularly in terms of design.

Triumph at the war’s end was celebrated with ticker-tape parades, but also in the design of cars and buildings, including the exuberant design of coffee shops in Southern California. The style of restaurant buildings that has also come to be known as “Googie” was modern, but without the severity of International Style. It used a wide range of materials developed in wartime, and forms inspired by the angles of fighter planes, the energy of the atom, and the bursts of bombs.

The inspiration for the striking designs of California coffee shops – known as Coffee Shop Modern – is frequently attributed to the space age, but over time the realization has grown that it was equally inspired by U.S. world ascendancy rooted in warfare. It may seem strange to attribute inspiration for a sprightly and bright type of architecture and interior design to something as ominous and deadly as the bomb, but a number of writers have made this connection.

In the words of Michael Sorkin’s essay “War is Swell” [in World War II and The American Dream, 1995]:

“That the atom so readily became a chipper symbol of American modernity in the immediate aftermath of its use as the greatest instrument of mass death in human history speaks volumes about the relationship of the accomplishments of war to the formal culture of peace. The decor of the fifties is all bursts and orbits, nuclei and energetic spheres. The atom was fully relegated to the class of things, isolated from life.”

[See also Elizabeth Yuko’s “Why Atomic Age Design Still Looks Futuristic 75 Years Later”]

Elements of coffee shop design can be seen in the look of automobiles of the same time. Some of the striking elements of California coffee shop design were echoed in the fins of Cadillacs inspired by the P-38 fighter plane. In Googie Redux, author Alan Hess, who has been largely responsible for recognition and appreciation of the creativity of Coffee Shop Modern, notes that Time Magazine called the 1959 Cadillac design the “ICBM [Intercontinental Ballistic Missile] look,” and also that “The Olds Rocket, the Olds Cutlass, and the Buick LeSabre were all names borrowed from aeronautics.”

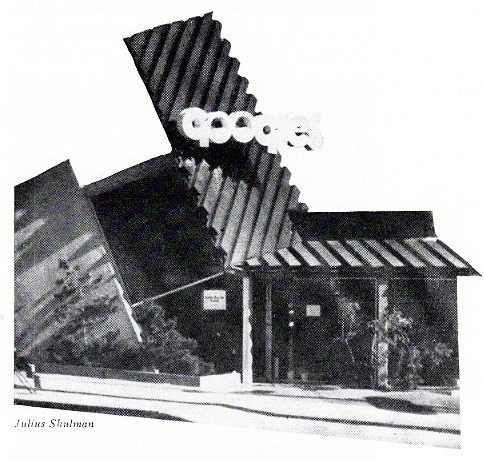

The design of coffee shops was nicknamed “Googie” after architect John Lautner’s 1949 unique Los Angeles creation bearing that name. It featured expansive glass window walls, unusual angles and roof lines, prominent signs, and bright colors. [partial view shown above — it extended farther to the right]

The vocabulary of Coffee Shop Modern signals its inventiveness. Terms in a glossary by Alan Hess in his book Googie Redux include: amoeboid, boomerang, cantilevered canopy, diagonals, dingbat, flagcrete, folded plate roof, free form, hyperbolic paraboloid, starburst, steel web lightener, structural truss, and tapering pylon.

California coffee shops, often bearing nicknames of their owners (Norm’s, Biff’s, Ship’s, Hody’s, Sherm’s, etc.), were casual, unpretentious, comfortable, moderately priced, and open 24 hours. Compared to the inexpensive eating places of the Depression, they offered a cheerful example of luxury for the masses, or what has been termed “populuxe” (See Thomas Hines’ book of the same name). Contrary to the usual negative public reaction to modern architecture, the upstart designs of the coffee shops were well accepted.

Counter seats were usually spaced generously and built with cantilevered supports allowing for unobstructed floor cleaning. [see above] Many had walls of decorative stone. A 1955 news story about the newly built Carolina Pines Jr. at LaBrea and Sunset noted its imported Italian mosaic tile columns, Palos Verde stone walls, and custom-designed wall plaques, among other features. It also had a carpeted dining room and an outdoor patio eating area in a garden protected from road noise and dirt with decorative fencing. [see below]

The coffee shops also introduced exhibition cooking. Although Eastern diner-style eateries had long done their cooking in sight of patrons, coffee shops introduced stylish designs and materials to the cooking areas and kept them sparkingly clean.

And, oddly enough, considering that the coffee shops were open all night, many of them had cocktail lounges.

Coffee shops designed along the lines of Southern California’s soon spread across the country. In St. Louis there was the Parkmoor, Cleveland had Manners, and Denny’s, with its beginnings in California, flourished everywhere.

Of course, as was true with neon signs, there were critics, notably Peter Blake in his 1964 book God’s Own Junkyard. He lumped Googie-style designs with neon, billboards, subdivisions, and a general decline in the built environment.

Starting in the mid 1960s but gaining in the 1970s Googie style was rejected, and what has been dubbed the “browning of America” by Philip Langdon had begun. Now chain restaurants of the coffee shop type began featuring earth tones, mansard roofs, exposed wooden beams, hanging plants, and subdued lighting. The coffee shop type of suburban restaurant continued in chains such as Denny’s despite competition by fast food establishments. McDonald’s, which had itself begun with Googie styling, toned down its buildings.

The change was due in part to the Vietnam War, but I can’t help but wonder if Americans hadn’t already become disenchanted with power and wealth based on military might.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

April 14, 2024

Advice to diners, 1815

What follows are “Useful Directions to Epicures,” published in the (New York) Weekly Museum. The publication’s motto was: “Here Justice with her balance sits, and weighs impartially the deeds of men.” (The word “Museum” was sometimes used to mean a publication. Another example was the Farmers’ Museum, a New Hampshire newspaper of the early 1800s.)

At the time of publication New York city had a population of about 100,000. The war of 1812 had just ended. Most residents of the city were merchants, grocers, or tradesmen such as shoemakers, cabinetmakers, or carpenters. Eating places included boarding houses, small hotels, victualling houses, and taverns.

– Make it a rule to be early in your attendance: every epicure will allow that it is better to wait a little for dinner, than to have the dinner spoiled waiting for him.

– Carefully inspect the bill of fare that you may know what is coming, and be able to place yourself accordingly.

– Seat yourself directly opposite your favourite dish; in that case you will be able to help yourself to the nice cuts.

– Help yourself plentifully at first, as it is a thousand to one whether you have a chance of a second plateful, and there may be some present who understand the joint as well as yourself.

– Watch the eye of him who wishes to hob or nob, and ask him to drink a glass of wine with you. You may get drunk otherwise, but not so expeditiously and politely.

– If you wish to be very witty at the expence of any of the company, attack him after the second bottle, ten to one but he forgets it all before morning, or if not, you can plead that you had too much wine in your head.

My interpretation

The advice, clearly critical of common practices, is addressed to men, some of whom may have been renting bedrooms in the same building. This explains why the writer might see a dinner companion again the next morning.

The word “epicure” is probably meant to be humorous.

The “bill of fare” was likely a single sheet of paper on which the day’s or week’s meals were hand written.

At this time in history, everyone sat at communal tables for meals and helped themselves from shared platters and bowls. They would heap their plates high and the last person might not get the best pieces, or much at all.

It’s clear that meat dishes, referred to as “nice cuts” and “the joint,” were the most highly prized foods. The narrator – along with the others — would almost certainly try to sit as close to them as possible, even if that meant arriving early and waiting for the food to arrive.

The reference to the difficulty of getting a second helping reflects the customary greediness of patrons — and that would include the advice giver.

There was quite a drinking problem in early America, and getting drunk was a frequent occurrence.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

March 31, 2024

Neon restaurant signs

The four gases used initially by neon signs – neon, argon, krypton, xenon – were discovered by English scientists in the 1890s and adapted for use in signs by Frenchman Georges Claude a short time later. Though not the first, an early neon sign was used in Paris in 1913 to advertise Cinzano vermouth. [shown above: Mac’s, Corpus Christi TX]

But it wasn’t until the late 1920s that the signs became popular with restaurants in America. Particularly in the West where car culture was developing, the eye-catching signs helped attract the attention of drivers.

In the early days neon signs in a town’s business district could also be taken as a sign of progressiveness. A 1929 advertisement for an electrical display company in Great Falls MT advised businesses that their adoption of a neon sign would impress people, encourage progress, and “beautify Great Falls.”

Their use became well established in the 1930s. In the 1934 book Curious California Customs, the author commented, “To the casual visitor, Wilshire Boulevard, after dark, is a flashing cavern of Neon signs, most of which are calling attention to eating places.” A later postcard of Hollywood Boulevard at night in the 1950s demonstrates the effect of a street full of neon signs [shown above].

In the late 1920s the signs began moving across the country. Among early adopters were eight Benish Restaurants in St. Louis, four White Way Hamburger outlets in Colorado, the Horn & Hardart Automats in Philadelphia, and four Janssen’s Hofbraus in New York City. Salt Lake City outfitted multiple New York Coney Island Sandwich Shops with the signs.

Bright neon signs and images remained quite popular throughout the country into the 1940s. But if they were meant to make a business stand out from the crowd, that became more and more difficult as the numbers grew.

Neon signs were undoubtedly most effective for roadside restaurants on dark roads that stayed open at night [above: [Bratten’s Grotto, Salt Lake City, 1956]. Or for eating places in somewhat obscure locations that required signs that could be seen from afar. Unfortunately, they didn’t look as impressive during the daylight hours [below: Bratten’s Grotto, daytime].

Before neon, efforts to craft signs that could attract distant or speeding traffic were undoubtedly less successful, less visible in the dark. George’s grotesquely large sign shown below, for example, was neither attractive nor sufficiently visible at night. As a slightly later version of this postcard revealed, the restaurant soon found it necessary to add spotlights atop the sign.

Neon wasn’t for every eating place. To critics it lacked artistic pedigree and dignity. Elite restaurants wanted nothing to do with it. It might announce the presence of the Green Frog or the Zig Zag Sandwich Shop, but certainly not New York’s La Chaumiere.

A 1960 book on restaurant decor pronounced neon in bad taste, saying, “Incandescent lighting is more expensive but has a kindlier glow and, thanks to the bad association arising from the tasteless use of neon, is generally considered ‘classier.’” As cities declined with the growth of suburbs, such attitudes toward neon grew more negative.

Nor was neon welcome in classy towns and communities such as Palm Springs, Carmel-by-the-Sea, and Sonoma in California; Santa Fe, New Mexico; the Hamptons on Long Island; and Cohasset, Massachusetts, to name but a few that banned it.

Rejection of neon grew in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1965, food critic and editor Craig Claiborne was uneasy about eating in the one (barely) acceptable restaurant he could find in Roswell NM, which he said had “the air of something once removed from Las Vegas or Miami Beach with its neon-silhouetted champagne glass and flashing neon bubbles.” His unease increased upon stepping inside and seeing a lighted goldfish tank, male customers not wearing coats, and bartenders with “narrow, abbreviated ties.”

Antipathy to neon in the 1970s, as before, was associated with urban decay and seedy neighborhoods characterized by run-down buildings and businesses such as bars and strip clubs. More cities and towns banned it.

Soon there were few “tube benders” left who could create or repair neon signs, which were increasingly being replaced with lighted plastic signs that were easier and cheaper to make and less prone to damage outdoors. Yesterday’s real neon signs that had survived soon showed up as quaint wall decor in warehouse-style theme restaurants.

A few commentators, such as a reporter for the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, began to wonder about the return of neon. She speculated in 1975 that “that much-maligned symbol of everything that’s bad about American commercial districts” might “someday be recognized as art.”

Sure enough, in 1976 the Smithsonian put on an exhibit that included neon signs, among them examples from a Kosher restaurant, a foot-long hotdog place in Cleveland, and from a Spanish-American restaurant in Greenwich Village, a many-colored creation that combined a lobster, pig, fish, chicken, crab, and a steaming coffee cup.

Nowadays, vaguely quaint-looking plastic “neon” signs might show up as interior wall decor in the sort of restaurants that want to suggest they are fun places.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024