Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 6

October 29, 2023

Taste of a decade: the 1990s

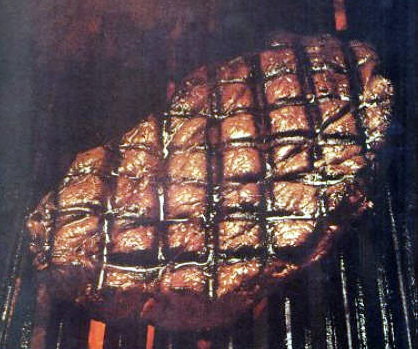

The decade began in an economic slump, putting a damper on the expensive dining trends of the 1980s. Informal dining venues met the situation by crafting new “casual cuisine” menus featuring less expensive, quickly prepared pasta dishes and grilled meat, all tailored for the Baby Boomers who formed the prime market for dining out.

Although surveys showed that Americans want healthful food choices in restaurants, beef remained extremely popular, and sales at casual steakhouses rose.

In the early 1990s restaurant chain operations emphasized efficiency and speed with microwave ovens, automatic dishwashers, and computerized systems that integrated taking orders with food preparation, as well as managing accounts and inventory. Coordination of operations enabled customers at drive-up windows to order, pay, and pick up their food rapidly.

Unable to compete with fast-food chains’ quick service and low prices, old-style casual eateries such as Horn & Hardart automats, Woolworth lunch counters, and cafeterias were disappearing. New York’s last remaining Automat, at E. 42nd St. and Third Ave., closed in 1991.

As the economy improved it became clear that luxury restaurants hadn’t vanished. The December 1990 announcement that the James Beard Foundation was forming an awards program was a sign that top chefs were not to be forgotten. Yet, despite the boost to fine dining given by the awards, fine-dining establishments continued to struggle.

New, artsy trends in plating meals emerged, among them the brief but dramatic art of stacking food into towers that wowed the eye but proved difficult to eat gracefully.

Even as elite food fads came and went, one trend appeared unstoppable: the gathering up of thousands of chain restaurants by regional owners and giant food corporations. While the media focused on top chefs and their novel dishes created in landmark restaurants, huge corporations such as Tricon Global grew even larger with many venturing into worldwide operations.

Mexican immigration doubled, reaching a new high of 8.8 million by the end of the decade and furnishing a large number of restaurant kitchen workers. Small Mexican restaurants opened to supply traditional food to the new immigrants, but by 1999 Taco Bell’s 7,000 U.S. outlets had captured 90% of the thoroughly Americanized Mexican restaurant market, serving 55M customers a week, with sales of $5.1 billion annually.

Black restaurant workers and customers had their day in court in 1993 with successful discrimination suits against Shoney’s and Denny’s. Shoney’s was found liable of charges it had set a limit to the number of Black workers it would hire in some of its restaurants, as well as hiring all-Black staffs in Black communities and all-white staffs elsewhere. Denny’s faced multiple law suits.

Highlights

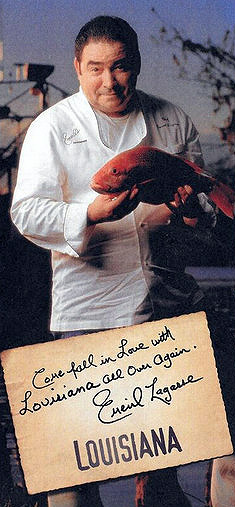

1991 Six men and one woman are the first regional chefs to be honored by the newly formed James Beard Awards: Jasper White (Boston), Jean-Louis Palladin (D.C.), Emeril Lagasse (New Orleans), Rick Bayless (Chicago), Stephan Pyles (Dallas), Joachim Splichal (Los Angeles), and Caprial Pence (Seattle).

1992 A U.S. Department of Labor report on technology announces that due to increases in productivity, chain-owned restaurants “for the first time . . . exceeded the number of independently owned restaurants.”

1993 Shoney’s, at the time the third-largest chain, is fined an unprecedented $105M for racial discrimination in hiring, while Denny’s pays $54M for refusing service to Black customers, insulting them, and overcharging them.

1993 The new Food Network spotlights restaurant chefs and methods of preparation. Viewers become interested in new restaurant dishes, while rising use of garlic at home is attributed to viewers watching Emeril. Despite the interest in inventive cuisine, 1991 James Beard winner Stephan Pyles feels forced to close his Routh Street Café in Dallas.

1994 Sensing that Black patrons may have been offended by revelations regarding Denny’s discriminatory behavior, the corporate owner hires a Black Chicago advertising firm to create an image of the restaurants’ friendliness to Black customers and workers.

1995 Stacked food – aka vertical or tall food – is reportedly now passé in New York’s trendy restaurants, replaced by layering food on the plate. However, a short time later vertical food is said to be “sweeping the country.”

1996 Taco Bell is the country’s leading Mexican restaurant, with 6,867 stores.

1997 PepsiCo.’s spinoff Tricon Global, based in Louisville KY, racks up more than $7 billion in sales with its major chains Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and KFC.

1998 In a survey, Applebee’s and Cracker Barrel tie for 8th place as family favorites among the country’s 30 largest chain restaurants.

1999 The U.S. Department of Commerce declares this “The Year of the Restaurant” and the Beard award for Outstanding Restaurant goes to NYC’s Four Seasons.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

October 15, 2023

The celebrity connection

Celebrities – and their names and faces – have had multiple connections with restaurants, generally adding to the glamour or appeal of the restaurants involved. One of the most obvious and probably the oldest attraction is the chance that customers will spot celebrities in a restaurant.

Restaurateurs and silver screen celebrities capitalized on that attraction in the 1930s and 1940s by encouraging gossip columns to publish sightings of dining celebrities. Despite their lack of real significance or accomplishments, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor were one of the celebrity couples most often attracting columnists’ attention in restaurants.

About the same time, there were also eating places, especially delicatessens, that named sandwiches for stars of stage and screen. Reuben’s was the best known, but in 1931 there was also Dave’s Blue Room, another NYC deli. As late as 1960 a Hollywood deli menu was full of humorous names such as Lox Hudson, Lucille Matzo Ball, and Judy Garlic.

Other eating places such as The Brown Derby and Sardi’s displayed portraits of celebrities who were past or present patrons of that restaurant.

But the BIG bump in celebrity links to restaurants came in the late 1960s and 1970s with the franchising boom. Many restaurant chain franchisers believed that by linking a chain to the name of a well-known athlete, singer, or actor, they would sell more fried chicken or hamburgers. Usually the celebrity was paid a fee and possibly a percentage of profits for their participation, which could involve taking the role of chairman of the board or as little as lending their name or likeness or making an occasional appearance at openings.

Much of the time the deal turned into a losing proposition for those celebrities who put their own money into the venture, as well as for stock market investors and franchisees. Joe Namath dismayed investors when he announced in 1969 that he was retiring from football to become chairman of Broadway Joe’s. The following year he pulled out when the chain’s stock plummeted downward. Within two years of becoming chairman of the soon-defunct Mickey Mantle’s Country Cookin’, the former New York Yankee resigned.

Some other sports figures who lent their names to restaurants included Dizzy Dean, Rocky Graziano, Fran Tarkenton, and Brady Keys.

Among Black celebrities failure took on a sadder note, given that some of them had hoped to bring business opportunities to Black communities. Other Black entertainers with restaurant connections were Fats Domino, Mahalia Jackson, and Sammy Davis, Jr. Black athletes included Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, and Brady Keys, who created and headed All-Pro Chicken. In 1969 he had 10 outlets in San Diego, where he began the chain, as well as in Pittsburgh, Rochester, and New York City. Like Muhammad Ali, Keys hoped to spur Black business, and enjoyed much better luck than Ali, who lost a lot of money fast with his short-lived Champburger chain.

Among singers and musicians who joined restaurant ventures in the 1960s and 1970s were Trini Lopez, Tony Bennett, Julius LaRosa, Eddie Arnold, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Hank Williams, Pat Boone, and Al Hirt. Most of them took a bruising. Some other entertainers were Minnie Pearl, Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis, Jackie Gleason, Arthur Treacher, Johnny Carson, and Rodney Dangerfield. [Tony Bennett display above]

Observers were quick to point out that the celebrities who did well with a restaurant or chain were those whose places had good food and management. Of themselves, celebrity connections counted for little or nothing. A frequently cited example of a success story was the Gino’s Pizza chain [not to be confused with Papa Gino’s]. Its good fortune was attributed to food quality and good management, rather than a name. In fact, most customers had no idea that Gino was Gino Marchetti, formerly of the Baltimore Colts.

But while a celebrity name could not guarantee restaurant success, it could be helpful. As Steve Chrisman, manager of two Sam’s Cafes in NYC (the name was the nickname of his wife Mariel Hemingway), would observe in the 1980s, “You need to get customers in to become visible. Mariel’s notoriety was important.”

The new wave of celebrity involvement in restaurants came in the late 1980s when it became popular to invest in restaurants, particularly for film stars. The restaurants were nearly all located either in NYC or the Los Angeles area. Involvement was largely financial and rarely meant day-to-day management. In some cases stars grouped together as was true of Malibu Adobe that came into being in 1987 through a venture by Dustin Hoffman, Tony Danza, Bob Newhart, Stacy Keach, Alan Ladd Jr., and Randy Quaid, with Ali McGraw [shown above] in the role of decorator.

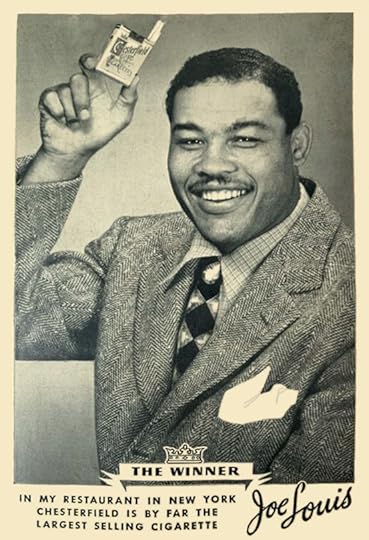

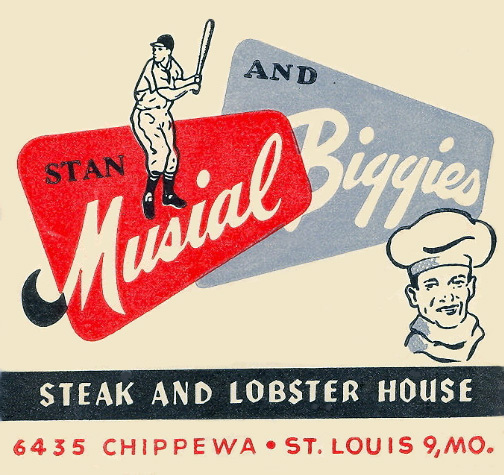

The 1980s wave was not about franchised chains, but mostly single restaurants. And that probably tended to give them a somewhat higher survival rate – as it had earlier for Joe DiMaggio, Joe Lewis [above, ca. 1940], Jack Dempsey [shown at top], and Stan Musial. Some of the new restaurants bore celebrity names, for example Charo’s Cantina, Tommy Lasorda’s Ribs and Pasta, and Bono, owned by Sonny Bono. Most did not, e.g., Dolly Parton’s Dockside Plantation, Tom Selleck’s Black Orchid, Clint Eastwood’s Hog’s Breath Inn, or Midwestern exception Oprah Winfrey’s The Eccentric. But their connections were widely known by patrons and they could sometimes be spotted dining in “their” restaurant.

The next wave of celebrity restaurants would feature famed chefs. But that’s another chapter in restaurant history.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

October 1, 2023

Spectacular failures: Laugh-In

The restaurants called “Laugh-In,” based on the hit Dan Rowan and Dick Martin TV show, formed a teensy blip in an enterprise that culminated with big-time gambling casinos. [1969 menu cover]

Perhaps because the TV show was such an instant hit, it inspired the idea that the same enthusiasm would transfer over to the restaurant. It didn’t.

The chain was created in 1969, under the Lum’s restaurants umbrella, by brothers Clifford and Stuart Perlman who had built the successful Lum’s chain from a small Florida hot dog stand thirteen years earlier. The brothers adopted the Laugh-In concept and franchise system not long after they had begun another chain called Abners Beef House in 1968.

At that time the parent company, Lum’s Inc., had 300 locations. The brothers decided to list it on the New York Stock Exchange. In addition to the three restaurant chains, they also owned a chain of Army-Navy stores, meat packing plants, honeymoon resorts in the Poconos, and a large country club in Miami, the city where the corporation was located.

Selling stock in Lum’s, Inc. was a way to amass money to fulfill the brothers’ ambition of buying Caesar’s Palace, the Las Vegas hotel and casino that had opened in 1966.

When they created Laugh-In, financial analysts warned investors that counting on the continuing popularity of a TV show was risky. What if it went off the air? Perhaps that did worry buyers. Forty franchises were expected to be sold in 1969, but the actual total for that year was probably lower and the overall total number of units ever opened is unknown. [above left, Rowan, right, Martin]

Laugh-In relied heavily on the goofiness of its namesake TV show for the design of its units, fronting its flat-roofed concrete-block-style buildings with wild patterns and colors. Table tops were manufactured with imitation graffiti reflecting phrases from the show. [Below, table-top graffiti as shown on the back of menu above]

Everything was meant to appeal to youthful customers. According to an early advertisement for franchisees, Laugh-In was “a fun restaurant, designed for today’s vast young-minded, leisure-rich market.”

Additionally it advertised that it used a “proven food format” as employed by Lum’s. Lum’s had a signature dish, hot dogs cooked in beer, and it also sold beer. Laugh-In did not. But judging from their menus, neither Abners nor Laugh-In offered anything special in the way of food. Despite the “funny” names, Laugh-In selections were the same as those found in many other casual restaurants. Then there’s the fundamental question of whether customers choose what to order according to how funny the name is.

Judging from a 1969 advertisement for Abner’s franchisees, the Lum’s corporation was not especially good at presenting desirable-sounding food. The ad exclaimed over its menu’s “hunks of steak in a long fun bun” and “good things to drink, too, a malt, milk, a soda, coffee and tea.” As for Laugh-In, despite the funny names (Bippy Burgers, Fickle Fingers, Here Comes The Judge), its menu boiled down to the usual assortment of sandwiches, deep fried fish, onion rings, and a few oddities such as “tomato and egg slices” and “cheese on a bed of lettuce.”

The first Laugh-In restaurant opened in Hollywood FL in December, 1969. A few months later 25 more franchises were said to have been sold around the country. But #1 did not do at all well. It closed just short of a year later, replaced with an “Adult Art Theatre.” [above, partial advertisement for the grand opening]

Overall, the brothers fared better with another big venture, Caesar’s Palace, acquired a couple of months before the first Laugh-In opened. Caesar’s Palace had a rough time at the beginning of their ownership, and the stock of Lum’s, Inc., its corporate owner, fell sharply. The brothers raised $4 million by selling off most of their restaurants, including Laugh-Ins, in 1971. But they ran into trouble attempting to open another casino in Atlantic City. New Jersey’s Casino Control Commission insisted that because the Perlmans had had financial dealings with reputed organized crime figures, they had to resign if a permanent permit was to be issued. Stockholders voted to buy them out, paying almost $100 million for their stock.

A few Laugh-In restaurants probably continued on for a while, though it had to be a blow when the show went off the air in 1973. The longest survivor may have been Jeff’s Laugh-In in Chicago, lasting until 1988.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

September 17, 2023

Restaurant names

In 19th-century America most eating places were named for their owners. But in the 20th century, despite the continuing prevalence of proper names, more creative names began to appear. For instance, a 1912 directory of Black-owned restaurants in Chicago included the Crazy Corner Café and the Wa-Wa.

Greenwich Village of the 1920s pushed the vogue further. Columnist O. O. McIntyre was one who sneered at names of eating places there such as the Purple Pup, the Mauve Moon, and the Cerise Cat. In fact, they heralded a trend soon popping up everywhere, especially in casual eateries and tea rooms. Names linked to colors, birds, and animals proved especially popular with tea room proprietors.

Newspaper columnists were alert to new and strange restaurant names. In 1927 a Seattle writer noted, “The bluebird and the red robin both sing the song of food. Being an especially noble bird the eagle soars over four hamburger houses, and thus is more active than any other animal as far as eat signs are concerned.”

Other eateries went further, with names that were attention-getting but far from charming such as the O-U-Pig Stand in Knoxville TN or Ptomaine Tommy’s in Los Angeles.

Busy Bees were found in almost every city, but they didn’t seem to head into the countryside much.

Restaurant names grabbed the attention of visitors from England. In 1929 the husband and wife authors of On Wandering Wheels noted inns and tea rooms in Connecticut with names such as Steppe Inn, Kumrite Inn, Wontcha Drive Inn and others they dubbed collectively “Ye Old Roade House.” A few years later another English vacationer marveled over a long list of “strange names” he compiled including Do Drop Inn, Dew Drop Inn, and Due Drop Inn. [Doo Drop Inn, Muskegon MI]

Why the rise of fanciful — and often hopelessly corny — names? I suspect it was competition that drove small businesses to attempt to stand out from the crowd. But it’s also probable that some proprietors who came from foreign lands were quite eager to hide their surnames during the anti-immigrant 1920s.

If anything, the Depression of the 1930s stimulated the use of creative names, as a glance at city directories reveals. Columbus OH had a Zulu Hut and a Pig Stile. Buffalo patrons could choose Da Nite Diner or Just-A-Mere Grille or one of seven “new” places, whether New Buffalo Lunch, New Chicago Lunch, New Genesee Restaurant, New Haven Lunch, New Main Lunch, New Popular Lunch, or New Texas Lunch. Exactly what about them was new is lost in time.

Even the trade magazine The American Restaurant got into the habit of collecting strange names in 1947, calling attention to lists that included Grabateria, Dizzy Whiz, and Blu Baboon. The columns also added to the growing list of names using the word “inn” with Weasku Inn, Hello Inn, Venture Inn, Brother-in-Law Inn, and Welcome Inn.

Continuing the once-irresistible urge to combine punning names with “inn,” here are others I’ve found, dating from the teens through the 40s: Always Inn, Bungle Inn, Chick Inn, Duck Inn, Du-Kum-Inn, Fiddle Inn, Fly Inn, Jitterbug Inn, Kum Inn, Pour Inn, Ramble Inn, Stumble Inn, Tip Toe Inn, Toddle Inn, and Tumble Inn.

Perhaps the long-lasting attraction to bizarre names actually peaked in the 1970s when restaurant groups spread themed chains across the country, often with names I would nominate for the most absurd of all, exemplified by Baby Doe’s Matchless Mine [Denver location pictured].

By now we’ve grown accustomed to many names that once drew attention, but have become ordinary. It’s unlikely that anyone still thinks of Drive Inn, now usually without the second “n,” as an originally punning name. Maid Rite and White Castle seem unremarkable as does Applebee’s, especially since deleting the initials T. J. which, thankfully, had fallen out of fashion.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

September 5, 2023

Image gallery: Redness!

The author of the book A Perfect Red identifies it as “the color of desire” and “the color of blood and fire.” She also notes that the color has often been associated with masculinity because it signifies power, prestige, and “heat and vitality.”

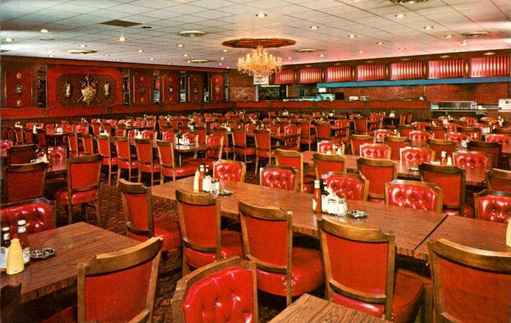

So it makes perfect sense that at one time it was popular as steak house decor. [above, Presto, Chicago, ca. 1970]

But it took a while to catch on. In the early 20th century the color red was strongly rejected by many Americans as inappropriate for clothing. Those who dared to wear red – or other strong, bright colors – were seen as low class and with questionable morals. The judgment was particularly harsh if the wearer was Black or an immigrant.

The use of red in home decor was also severely criticized. An elite Chicago woman’s club firmly rejected a trend toward Oriental-styled dens with red walls, piled-up cushions, and low lighting. One of the club’s members noted in 1903 that during a visit to a house with so-called “cozy corners” full of soft pillows she began to doubt that “the mistress of that home was a moral woman.”

Needless to say, though early women’s tea rooms sometimes adopted playful decorating themes, red was decidedly not a popular color scheme in them.

Despite its association with immorality (or maybe because of it?) red made a strong showing after World War II, especially in the mid-1950s through the early 1970s. It was often used in restaurant decor, especially for places that appealed primarily to men.

Red tended to be employed lavishly. It was variously used for carpets, painted wall and ceiling surfaces, columns, wallpaper, light fixtures, draperies, tablecloths and napkins, glassware, menus, upholstery for chairs and banquettes, and waiters’ uniforms. [above: That Steak Place, VA]

Sometimes an old-time theme was adopted, usually signaled by red-flocked wallpaper meant to conjure a bygone time of jollity that might suggest anything from the “gay ‘90s” to the “roaring ‘20s” to a brothel.

A 1955 book of decorating advice suggested that, in contrast to cool colors and bright lights, restaurants with warm colors and dim lights suggested luxury. The latter decor encouraged patrons to relax and was believed “to increase the size of his check.” Likewise, a bar decorated in red might encourage drink orders.

Of course red is more than warm, it’s hot! It can be difficult to imagine relaxing in some of the eating places that enveloped diners in redness. Such as, in particular, NYC’s Cattle Baron [shown above], which opened in 1967 in the Hotel Edison. If the red decor weren’t appealing enough, the restaurant’s owner seemed willing to revive an association with questionable respectability when he ran an advertisement picturing a nude female model marked with black lines indicating cuts of meat.

Whatever poshness and sense of luxury a red interior suggested, it began to wear off in the 1960s, and even more in the 1970s. In 1961, when a version of the NYC club known as Danny Segal’s Living Room opened in Chicago, a reviewer criticized the “engine red decor” with red light bulbs as “excessive” and amounting to “a satire on night club decor.” Also in the 1960s, an Oregon restaurant reviewer sneered at “that ubiquitous black and red decor which has almost become a stereotype of the snobbier bistros.”

Restaurants began ditching their red decor in the 1970s. The Colony Square Hotel in Atlanta installed a new restaurant called Trellises, causing a reviewer to applaud the disappearance of the “steakhouse/bordello gold and red decor.” The western Straw Hat Pizza chain decided in 1975 that Gay 90-style restaurants with red-flocked wallpaper were out of fashion. The Homestead in Greenwich CT hired NYC designers to come in and rip out their red carpets and red-flocked wallpaper for a country look with hanging plants, wood floors, and brick walls. [above, Harry’s Plaza Cafe, Santa Barbara]

Of course, the U.S. is a big country, full of diverse tastes and fashions, so it’s not a big surprise that there were (and are) some restaurants that kept their red decor.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

August 22, 2023

Status in a restaurant kitchen

The status hierarchy in a restaurant kitchen depends on a variety of factors. Skill is clearly one of them, but, historically — if not currently — there have been others, some of them surprising.

In 1944 and 1945 sociologist William Foote Whyte spent time observing kitchens in a number of Chicago restaurants. To one of them he gave the fictional name “The Mammoth” because of the size of its kitchen which employed 45 persons excluding dishwashers.

Whyte noted in his book Human Relations in the Restaurant Industry that by that time in this country, the French chef had lost influence and “this system has steadily degenerated,” eliminating some of the hallmarks of status.

But there were still distinctions of rank, fainter and sometimes subtle yet real.

In step with that time, gender was still a major factor contributing to status. It was linked to skill and experience as well as the difficulty of tasks. It was also reflected in the use of knives and heat, and the sorts of food handled. Although because it was wartime, more women were assuming these positions, at The Mammoth it was men who did the cooking, and men who both portioned and cooked red meat.

Women handled the lower-status food: chicken, fish, and vegetables. The Mammoth’s food suppliers at that time had not yet taken over much of the food preparation as they have in more recent decades, leaving many tedious tasks to the staff that sliced, chopped, and otherwise prepared fresh food for the cooks and sandwich makers.

Among vegetables, he explained, decorative items such as parsley, chives, and celery ranked highest. (Their elevated status reverberates today in the many photographs of elite chefs bending almost double as they carefully tweeze small decorative touches into place.)

One notch down came green beans, followed by spinach and carrots. Undoubtedly the status of these vegetables derived in part from their popularity with customers. But also, he explained, on the women workers’ opinion of them, based on “lack of odor, crispness, and cleanness of handling.”

Lowest in status were potatoes, then at the bottom onions. Whyte states that the “low standing of potato peeling is too well-known to require comment.” I’m not quite sure what it derived from, although it is well known that military recruits strongly disliked kitchen duties that involved peeling potatoes.

Seven women handled cooked chicken. Those who sliced the chicken were at the head of the line. Slicing white meat was higher in status than dark meat. Next came two women who portioned and wrapped slices for sandwiches. On the bottom rung were three women who picked the remaining meat off carcases, with the one who picked white meat ranking higher. The worst job, that of the seventh woman in line, was picking bits from chicken neckbones. When the worker assigned to that task complained about always getting the necks, she was assigned to another job.

Deep disdain for the chicken picking job was highlighted in the response of one of the workers on the line whose job was wrapping slices. She commented to Whyte that it was tedious. When he asked her if she would prefer picking, she frowned and said emphatically, “Oh, no, I wouldn’t want to do that.”

The woman who handled the fish station, “Gertrude,” was highly regarded by management but not by employees because they held a low opinion of fish, considering it smelly. According to Whyte, this put her station “at the bottom of the status hierarchy,” even though with the wartime meat shortage, fish was assuming a much more important role in restaurants. He attributed the workers’ attitude to ignorance, particularly because The Mammoth had a high standard regarding fish and bought only the freshest. Gertrude strongly disliked being referred to as “the fish lady,” and asked that in the book Whyte refer to her station the “sea-food station.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

August 8, 2023

Dining at the speakeasy

Speakeasy restaurants had an unexpected and lasting effect on patrons’ dining and drinking preferences after national Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

Many speakeasies didn’t serve food, but those that did were mainly located in cities and on urban outskirts. In cities, many were run by people from Italy or France, from cultures that generally did not demonize alcohol and saw wine as a normal accompaniment to dinner.

Deluxe restaurants of the earlier 20th century had closed when they lost their revenue stream from liquor, marking the end of an era of restaurant going. Their haughty formality and giant dining halls became a thing of the past. Since they had the most to lose if caught, hotels tended to observe Prohibition. But they suffered badly as guests abandoned their dining rooms for more accommodating eating places. It turned out they also liked the ambience they found in speakeasy restaurants.

Speakeasies in New York were said to have excellent food, largely because their profits allowed them to hire away the city’s best chefs from other spots. Another problem for restaurants and hotels that observed Prohibition was that they had to raise their prices to make up for the lost revenue from drinks. At the same time, speakeasy restaurants were able to lower their prices because they were making so much from drinks.

Some restaurants played it both ways. They were not speakeasies — no guards at the door, no secret password — but they were very, very careful about serving forbidden liquids only to known and trusted guests. New York’s Colony was one that tried this method, not entirely without peril. In 1925 it was padlocked by Prohibition agents for 30 days.

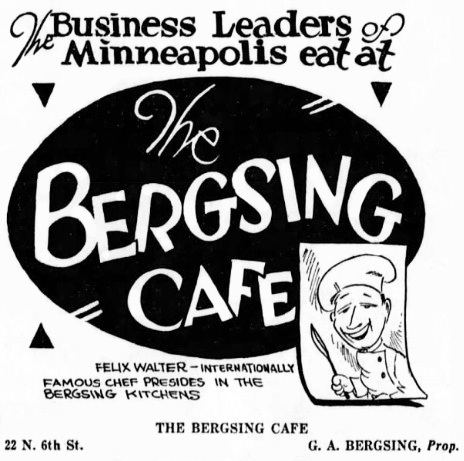

Another example of a respectable offender was the Bergsing Café in Minneapolis, described by the authors of Minnesota Eats as a “gentle speakeasy.” Patrons could be sure their reputations would not suffer if they ate there. As the 1929 advertisement shown above proclaims, it was popular with business leaders who evidently were not bothered by the practice of serving drinks to certain customers.

By contrast, the roadhouse known as the Hollyhocks Inn, in nearby St. Paul MN, was a true speakeasy. Although it drew a society crowd, they rubbed shoulders with serious gangsters. In fact, a co-owner of the inn was convicted of plotting with a gang to kidnap brewery head William Hamm and sharing in the $100,000 ransom. At his trial he was asked if he had run a speakeasy, drawing laughter from spectators when he answered, “I don’t know what you mean by a speakeasy.”

Federal agents sometimes went to great lengths to get into speakeasies. In New York three agents presented themselves as vaudeville players gossiping about fellow performers at a spot on West 46th street. They were admitted and made an arrest.

New York had so many accommodating restaurants and law-breaking customers – many of them tourists – that for many Americans in small towns the city it became seen as Sodom and Gomorrah. This widened the cultural gap. As historian Lewis Erenberg put it, it created “the sense that New York was not America.”

Aside from Greenwich Village, New York’s speakeasies tended to be located on side streets, particularly in residential brownstones west of Eighth avenue in the Forties. A Brooklyn restaurant proprietor reported in the trade magazine Restaurant Management that probably half of the eating places there made “their money on other things [than] food.”

Of course, New York, where there were an estimated 25,000 speakeasies, was scarcely the only city that violated the Volstead Act. Most American cities were also said to have thousands of speakeasies in the 1920s. For instance, Chicago had the South Side and Towertown, its Greenwich Village type of area. Even Pittsburgh – where the word speakeasy first came into use in the 1880s – was well supplied. On the other hand, Los Angeles was said to be lacking in speakeasies because most Angelenos did their drinking at home.

By the 1930s many speakeasy owners were plagued by gangsters who tried to muscle in for a cut. Some proprietors hoped that Prohibition would end and they could open legitimate restaurants that would be patronized by the clubby following they had developed. One of the features of the speakeasy that they hoped to capitalize on in the future was what a Life magazine story characterized as “an intimacy in the restaurant business that it never had before.” The writer Heywood Broun thought that speakeasies had been “a civilizing influence” that had helped “allay the feverish pace of American life.” They were, he thought, friendlier, with their small, quiet dining rooms, good food, accommodating waiters, and moderate charges. His concern was that the end of Prohibition would destroy that.

Others correctly felt that the public would still value small and intimate places. The Childs chain, which began to serve wine and liquor after Repeal, noticed that its booths, which had once been unpopular, were now sought after. They attributed the change to “the speakeasy influence.” Restaurant Management magazine reported in 1934 that cocktail lounges with bright ultra modern decor were being rejected by women, who preferred warmer Colonial American styles and soft lighting. Cozy Midwestern supper clubs, often located on the outskirts of town where they could avoid raids during Prohibition, showed a staying power after Repeal.

Speakeasies, it appeared, had indeed changed the public’s dining and drinking habits. Rather than lone men standing at bars, bartenders were seeing men and women at tables enjoying leisurely 5:00 o’clock cocktail hours. Diners were more knowledgeable about food and wine, and showed more enjoyment in dining out, in contrast to what one writer described as “the hurried days of eat, drink and move on to another place.”

The fondness for speakeasies also lived on long after WWII in numbers of restaurants and bars with names such as Keyhole, Hideaway, and of course Speakeasy.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

July 25, 2023

Dining with the garment trade

At a recent used book sale I picked up a copy of a small book of humor published in 1919 called “We Need the Business” by Joseph Austrian. I was charmed by the illustrations by Stuart Hay, several of which related to the food habits of the men in the garment trade as portrayed in the book.

The book is a series of letters written by Philip Citron, owner of a company in New York City called Citron, Gumbiner & Co. that, made women’s waists (as blouses were known then). Austrian had long worked in the clothing trade, suspenders being his specialty.

In his letters to his partner and salesmen in the field, Philip Citron mostly complains about competitors who are stealing their business. He gives the impression that most contracts the salesmen get are later cancelled when buyers find a cheaper deal elsewhere. At the same time, he is unhappy that his salesmen don’t get higher prices on the sales they make!

In the illustration shown at the top, Moe Gabriel, an eager salesman from a competing manufacturer, is successfully selling a bill of goods to Ike Weinberg that will result in a cancelled contract for Citron & Gumbiner. Ike actually seems far more interested in his lunch than in getting a cheap deal.

One of Citron’s salesmen is his son Abe. Philip sends him a birthday letter in which he congratulates his son on wise conduct with “the ladies.” Mingling with them, he writes, is fine if they are the “right kind of nice ladies.” The illustration suggests that Abe has other ideas. Later the reader finds out that Abe is also keeping late hours with the company’s secretary under the guise of working. Philip has no idea of what is going on.

In another letter Philip describes a trip he and his wife took to Atlantic City. He suffers from digestive problems and the little vacation is meant to get him to relax. They go to a restaurant popular with the garment trade that he refers to as the “Flyswatte” where the cooking was “high grade.” His wife asks the chef for the recipe for “a new style of cold fish” that he enjoyed there. Later, when they get back home, she prepares the dish. It makes him ill.

Philip goes to Boston to meet with a buyer from Holyoke MA named Cyprian Stoneman, from Neill, Pray & Co. He describes Stoneman [shown above] looking more like “the designer of a book like ‘The Antique Furniture of New England’” who eats pie for breakfast than an “up-to-date model shirt waist buyer.” But he is determined to find a customer in Holyoke so he settles on Stoneman, meeting him for lunch at the Café Georgette which is popular with garment salesmen and buyers – and where portions are big. Stoneman is so thin that Philip can’t imagine “where he stored all the linzen [lentil] soup, brust deckel [fatty brisket], kohlrabi, deep dish blackberry pie a la mode, watermelon and ice tea he put away.” He proves to be “one of those lemon buyers de luxe,” buying very little and wanting numerous alterations.

Citron, Gumbiner & Co. designer, Miss Kopyem, goes to Haines Falls in the Catskills on vacation, where she finds “the streets and porches . . . full of operators, contractors and salesmen of the ready-to-wear trade.” She does not enjoy the crowds and noise. Philip likens the scene there to “Fifth Avenue at lunch time” where, in fact, he is part of the crowds. He is shown bottom right in the drawing above.

At his partner’s recommendation Philip opens a lunch room for employees and adds a suggestion box. He removes it after it instantly becomes stuffed with 25 letters asking for additional benefits such as massages, a barber shop, soda fountain, and movies. Employees also want American chop suey, Gorgonzola cheese, marinierte herring [herring in cream sauce], strudel, gefülte fish, caviar sandwiches, welsh rarebit, and chicken a la King.

In the book’s final letter to his partner Sol, Philip reveals that the company has had its best year ever and “will show a clean net profit of about $52,000.” His stomach, he writes, “feels fine to-day.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

July 11, 2023

Restaurant brawls

All the discussion about guns in public places these days has me thinking about restaurant security, a subject that, as a patron, I never actually consider. Specifically, I began to wonder for the first time whether ordinary eating places all the way up to elite restaurants have armed employees or a gun stashed away somewhere. Or, might patrons be armed? [shown above is a 1946 Jiggs comic strip scene]

Given that the answer has been “yes” back into the 19th century, and that more Americans are armed now, it’s likely to still be true.

But a more common type of violent incident that occurs in restaurants is a brawl which, thankfully, hasn’t usually involved guns.

Of course restaurants have always had a certain number of problem patrons to deal with. According to one 19th-century account, even Delmonico’s had a man employed to handle difficult guests, such as those who arrived inebriated. He headed off trouble by not admitting them or by whispering a “word of advice” to patrons who drank too much while in the restaurant. Mainly, he said, his job was to recognize by sight the city’s “bunko steerers and confidence men”: “I just meet them at the door and tell them it won’t do, and they know it won’t, so they go away quietly. There is no bouncing or knocking out required.”

His genteel method was similar in tone to that of “The Foreigner’s Club” of Sorrento, Italy, where this card was used.

Alas, such methods were only available in certain restaurants. At others, there were no door keepers, subtle ushers, or “convertible waiter bouncers.” It seemed from time to time that nothing could stop patrons from fighting other patrons or a server or even instigating a mass brawl.

I started thinking about restaurant brawls when I read a story in this year’s January 29 issue of the NYTimes Magazine. It described the scene of a Waffle House in Texas where a melee erupted and was captured on video. It involved patrons standing on the counter, throwing dishes and chairs, and attacking workers who fought back in like manner. Other popular videos show similar scenes in Popeyes and sub shops.

The author, Niela Orr, expressed a degree of longing for the days of Edward Hopper’s famous 1942 painting Nighthawks, where patrons sit glumly in isolation from other sad sacks at the counter. Like the Waffle House patrons, they are alienated but unlike them they aren’t throwing crockery.

They could have been though. Restaurant customers were documented hurling dishes as early as the 1860s.

In 1920 movie patrons laughed at the subject of riots in restaurants.

Restaurant brawls are diverse. Undoubtedly many of the sites where they occurred were lowly eateries but others were mainstream chains, such as the International House of Pancakes, Child’s, and White Castle. And Googie’s – where comedian Lenny Bruce went through a plate glass window. [1957 photo]

Not even Grandma’s Family Restaurant and Pancake House in Rockford IL was safe from disruption. In a 1992 melee there, an estimated 30 patrons “went wild,” breaking out four plate glass windows, jumping over booths, and throwing whatever they could get their hands on.

Incidents sometimes involved brawlers you might not expect, such as students at elite colleges (Harvard vs. Dartmouth in one case), or men in tuxedos upset that a server refused to give them more sugar during WWII rationing. Generally participants have tended to be young, white, male, and intoxicated.

Few incidents could outdo the brawl in New York City’s Bryant Park Grill said to be a repeat of a similar event in DC three years earlier. To quote a 1998 story in the Jersey (City) Journal, 40 of NYC’s firemen celebrating Medal Day in their finest uniforms “annoyed patrons, exposed themselves, urinated in public and invaded a women’s restroom.” They also threw a policeman over a row of planters when he tried to break them up. And, as so often happens, no one was arrested.

Personally, I will try to push all this to the back of my mind when I’m visiting restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

June 27, 2023

On the town with O. O. McIntyre

When he died in 1938 Oscar Odd McIntyre – also known as Double O McIntyre or simply Odd – was the country’s highest paid, most widely read columnist. Not only did he make New York City, particularly Broadway, familiar to newspaper readers across America, but he also informed them of the attractions of the city’s restaurants.

Considering that his success brought him a princely income, a Park Avenue address, a custom wardrobe by Lanvin, trips to Paris, and a chauffeured Rolls Royce, his writing conveyed a humble perspective. It left the impression that he was a regular small-town guy and that life in New York, when deconstructed, was less glamorous than it might seem at first, yet still captivating.

From the start of his newspaper career in Ohio he aimed at New York. As he put it, “When I was ‘the’ reporter on the daily in a small Ohio town reporting how John Hawkins spent the day in town and how Mrs. John Spivens Tuesdayed in Addison I was always dumb with admiration when I came across a guest at the Park Central Hotel who had the magic letters ‘N. Y.’ after his name.” In 1912 he landed a job as associate editor of a magazine in New York and made his big move.

His column’s target readers were, in fact, John Hawkins and Mrs. Spivens, and he relied heavily on Ohio newspapers to buy his early columns. He assumed that, like him, readers would proclaim “This is the life!” after a visit to a café in New York such as Bustanoby’s Beaux Arts. And that, like him, they would have a fascination as well with the other side of town, exemplified by the liveliness of Hester Street and the grittiness of the Bowery. He presented the city’s dark side in scenes such as one where he witnessed a patron at a nearby table in a “semi-respectable” restaurant inject morphine into his arm and then calmly resume reading his newspaper.

He revealed in a number of stories he wrote for various publications that he had a breakdown shortly after coming to New York to work for a magazine that failed three months later. He couldn’t find another job, and spent a year without leaving his sick room. He also suffered from hypochondria, claustrophobia, and agoraphobia, and depended upon his wife Maybelle to handle the business end of his writing. After seven years in which he self-syndicated, she took over and successfully negotiated a contract with a major syndicator for twice what he had been getting.

His columns were built on the notion that he spent time strolling the sidewalks of New York, but some critics suggested he actually viewed the sidewalks from the back of his limo. Another version claimed he was a recluse who rarely left his apartment and who wrote columns from memory. I’ve begun to wonder if it was Maybelle who rambled the city collecting material for him.

Whatever was the case, he entranced the nation with his observations. When they visited New York for the first time, even readers from small towns might feel they already knew the city because of what he wrote. The columnist who succeeded him recalled that when his outlander cousin came to NY, he said that because of O. O.’s columns he would need no guidance. He declared: “I’m starting at the Battery tomorrow morning, and I’ll have grilled pigs’ feet and German beer at Lüchow’s [shown above]. I’ll just glance in at Fraunces’ Tavern, but I might take a snack at the Brevoort or the Lafayette, and maybe get up to Louis & Armand’s in time for chicken Tetrazzini or a steak at Sardi’s.”

In his columns O. O. not only painted fascinating scenes of fine living in New York, but also popped bubbles about its glamor. In a similar vein he reminisced about the simple life in his old home in Gallipolis OH, but never returned there even for a short visit. He presented charming portraits of Greenwich Village, but also produced a column about its fake Bohemians and artistic pretenders. He acknowledged that there were some genuine artists living there too, adding, “they are not on display nightly in the Purple Pup, Mauve Moon and Cerise Cat restaurants.” [He did not include the Pepper Pot, shown above, but might have.]

He was also critical of New York night clubs, which he called sucker joints, as well as places with trick names such as the ones he ran into on a Los Angeles visit – the Fly Inn, Monkey Den, Hamtree, Mammy’s Shack, Quick and Dirty, and Hamburger Hank’s.

Although he frequented New York’s top restaurants, he was no gourmet. He wanted to consume the high life, but it seems mainly for its aura of princeliness rather than its culinary excellence. Although the McIntyres had a French cook, his favorite meal was said to be steak, potatoes, and chocolate cake.

His personal food preferences didn’t keep him from feeling qualified to identify the world’s best restaurants. In 1931 he named six, with The Colony at the top, then New York’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel (where he and Maybelle lived for 13 years), three in Paris: the Ritz, Foyot’s, and the Tour d’Argent, and Horcher’s in Berlin.”

He hailed New York as “the Epicurean center of America,” but he believed it was non-New Yorkers who kept the elite restaurants in business, while the typical New Yorker followed “the eat-and-run plan of gastronomics.” So, for out-of-town visitors, he recommended the following dishes, claiming few New Yorkers even knew of them. They included caviar on a “pancake” at the Colony; noisette of venison, Grand Veneur at the Crillon; French pastry at Voisin’s; and for those preferring an unpretentious meal, doughnuts and malted milk at Liggett’s and hamburgers with chopped onions at the Owl lunch in Herald Square.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023