Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 5

March 17, 2024

Anatomy of a restaurateur: Clifford Clinton

Rarely is the word fantastical used to modify the word cafeteria. Nor are restaurant proprietors usually thought of as powerful vice crusaders. [cover, 1940s booklet; below Pacific Seas]

A major exception of the latter was Clifford Clinton, creator of two of Los Angeles’ most memorable cafeterias. Both Clifton’s Pacific Seas and Clifton’s Brookdale were indeed fantastical, exotic, and composed of an odd blend of entertainment and salvation. In appearance they anticipated elements of Disneyland as well as Polynesian restaurant decor.

One of their strangest aspects was that they represented Clinton’s missionary work. After a few years of operating his father’s Puritan restaurant chain in San Francisco – previously owned by moralist Alfred W. Dennett — he came to Los Angeles in 1931 and re-opened a former Boos Brothers cafeteria at 618 S. Olive.

By the following year he was running that “Clifton’s” cafeteria plus another one on W. Third, one on Hollywood Blvd, a hotel probably housing his employees, “A miniature Cafeteria of the Tropics” in Whittier, and a “Penny Caveteria” in a basement on S. Hill street that offered dishes for 1 cent each.

In October 1932, perhaps the worst year of the Depression, a newspaper featured a smiling woman in the Caveteria with her 5¢ meal of soup, veal loaf, macaroni, sliced tomatoes, and buttered bread. According to another story, she was but one of an average of 4,500 customers fed each day (except Sundays, when all Clifton’s closed). Lines typically stretched down the street. For Christmas that year 7,000 guests enjoyed a Christmas turkey dinner priced at 1¢.

In 1939 Clinton remodeled the redwood-forest-themed Clifton’s Brookdale that had opened in 1935 as well as the original place on S. Olive, Clifton’s Pacific Seas, with a dazzling Polynesian look, neon palm trees, and many, many waterfalls. [Brookdale interior shown above; below more waterfalls, Pacific Seas exterior]

Along with meals, the restaurants acted as social centers and spiritual retreats for the thousands of uprooted mid-westerners who had relocated to Los Angeles. And they served as a kind of political base for Clinton’s reform campaigns. His cafeterias and his political activities were entirely consistent with the tenor of Los Angeles culture of the time. As George Creel summarized it in a 1939 Colliers article, the city throbbed with “two thousand religious cults . . ., each claiming daily and direct communication with Jehovah, and an equal number of social, economic and political movements: Epic, Social Credit, Utopia, the Townsend Plan and Thirty Dollars Every Thursday, etc., all guaranteed to promote the immediate salvation of mankind.”

Religiosity permeated the Clifton’s Cafeterias, as it had Dennett’s and would in a number of restaurants later in the century. If guests left the main dining room of Pacific Seas and entered the basement they would find a life-sized figure of Jesus praying in The Garden of Meditation [shown above]. Brookdale featured a Little Chapel set amidst the redwoods.

During World War II, Pacific Seas diners could also post their “feelings and wants” on a bulletin board or consult with a “Mrs. Von” in her bamboo hut for advice on personal problems.

Clifford Clinton’s mission to offer affordable meals continued throughout his career. The policy was that no one would be turned away because of a lack of funds. Although the practice undoubtedly ate into revenue, and was probably taken advantage of by some, Clinton managed to amass enough profits to live in a sprawling mansion on Los Feliz Blvd. and Western Ave in which he hosted convalescing employees [shown above]. (The house sold last year for close to $5M.)

Clifford Clinton was as colorful as his restaurants, despite his appearance as a conventional religious and civic-minded family man. He had spent much of his childhood in China with his missionary parents, an experience that he said made him ultra-sensitive to human hunger. That is unusual but it was just a prelude to his role as one of Los Angeles’ prominent crusaders of the 1930s dedicated to cleaning up the city’s vice and political corruption.

He succeeded in getting Mayor Frank Shaw recalled and replaced by the candidate of his choice, who he promoted on his radio show. In addition, the city’s police chief was indicted and found guilty of plotting the car bombing that severely injured the private detective working for Clinton’s lawyer.

Clinton’s success as a crusader has been partly attributed to his alliances. He worked with Protestant ministers under the banner of an organization he created known as C.I.V.I.C (Citizens’ Independent Vice Investigating Committee). And he also allied with the Communist Party during its popular front phase. As a result of these efforts, gambling, prostitution — and the city’s anti-Communist Red Squad — were eliminated, or at least removed from sight.

Through these years Clinton experienced endless phone threats, a bombing at his home, false reports of food poisoning at his restaurants, and an endless array of dirty tricks such as an invasion of one of his public forums by 300 hungry people who had been given tickets for a (non-existent) free meal of chicken and beer. [above: 1939 advertisement for magazine article; below: Clinton examines bomb damage]

Having turned the cafeterias over to his children in 1946, Clinton and his business partner, Ransom Callicott, focused on world hunger. They found a scientist who developed what would be known as Meals for Millions, a soy-based one-dish meal that could be prepared as soup or, with a little flour or corn meal added, bread.

Clinton died in 1969 but his restaurants, including a number of conventional ones in shopping centers, endured well into the 2000s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

March 3, 2024

Restaurant food revisited

Over time I’ve written a number of posts about specific dishes and types of food highly associated with restaurants, some of them rarely prepared in home kitchens. Other items listed below are not restaurant dishes, but items that restaurants need to provide on the table or use in the kitchen – and that have played special roles — such as butter, cheese, bread, sugar, parsley, water, and cooking oil.

Beans – Beans were a basic dish in cheap eateries in the 19rh and early 20th centuries and furnished a meal for any time of day or night. Writers were attracted to beaneries for their symbolic association with rock-bottom reality. Beaneries disappeared when the increasing wealth of post-WWII America led restaurants to shun beans except in chili.

Bread – Clearly the filler-upper in America’s early eating places, it accompanied even the cheapest meals. In more modern times, it has served as a consolation to hungry diners waiting for their orders to arrive at the table. Today as many restaurants “monetize” their bread baskets, it is no longer “free.”

Butter – It has appeared on restaurant tables in various guises — whipped, as rosettes, curls, or pats. It was a bit of headache for restaurants but they had to serve it as long as they served bread. Restaurants continued to serve it during WWII when the federal government backed down on reducing the amount they were allowed.

Cheese – Although the custom of finishing a meal with a cheese course never really caught on in American restaurants, their use of cheese in a variety of menu items continued to rise throughout the last century. Its ever-increasing popularity was boosted by Italian dishes, saloon “free lunches,” cheeseburgers, and of course the rise of pizza and Mexican fast food chains. [pictured: chili cheese fries]

Chocolate desserts – Not much chocolate on the menus of hotels and eateries in the 19th century, but that was going to change. No doubt the entry of women into the dining-out public in the 20th century had a lot to do with its rising popularity, especially in the form of baked goods. By the 1970s a huge number of Americans began to declare themselves “chocoholics.”

Club sandwiches – Perhaps they originated in clubs, but that mere suggestion gave them a cachet and no doubt helped spread their popularity. That and how neatly they were layered and cut into four dainty triangular pieces recommended them to diners who were upwardly mobile – or wished they were. Perfect for restaurants because, really, who wanted to go to all the extra trouble to construct one at home.

Coffee – Coffee, the beverage of sobriety and business, was basic to restaurants for most of the 19th and much of the 20th century. And, surprisingly, its price per cup stayed at 5 cents in many restaurants until the 1940s. By the 1970s it was up to 25 cents but it was increasingly losing out to soft drinks. Eventually it lost its major place as an accompaniment to meals, except maybe with desserts.

Cooking oil – If anything shouts restaurant fare, it is the long history of deep-fried food served in public eating places. Early fryers relied on lard, later replaced with cheaper cottonseed oil. The number of items that are fried has only increased over the decades, to include meats, fish, potatoes, a wide assortment of vegetables, even cheese.

Crepes – Restaurants specializing in crepes became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, fueled by increased travel abroad and interest in wider food horizons. Yet, unlike other foods regarded as rather exotic, crepes were affordable. The Magic Pan chain became popular and was acquired by a major food corporation. But by the mid 1980s the trend had expired and the delicate food was declared out of fashion.

– A truly “legendary” menu item in the sense that its origin story was concocted to give it enough glamour that a higher price could be charged. Maybe not quite that deliberate, but close. A legend appears to have been invented, or perhaps embroidered, in the 1940s. Eventually the dish, a brunch favorite, became popular enough that it could stand on its own.

Fortune cookies – The cookies probably made their initial appearance in the 1910s at Golden Gate Park’s Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco. It didn’t take long before they were regarded as an invariable component of a Chinese restaurant meal. In the 1960s the paper on which fortunes are printed was sterilized and the message was printed with non-toxic vegetable dyes.

French fries – In cooking terms, frenched does not refer to France but to cutting food into strips. In France our “French fries” are their “frites.” The cost of cooking oil hampered their adoption in restaurants here for a time, but they began to appear on more menus in the early 20th century, especially after demand rose as WWI veterans who had been introduced to them in France returned home.

Fried chicken – Fried chicken could not become popular, inexpensive – and profitable — restaurant fare throughout the country until chickens went into mass production, mainly after the second World War. Before that fried chicken lovers had to travel into rural areas, often to tea rooms, to find it on a menu.

Hamburgers – Perhaps because in the 1890s hamburger sandwiches were strongly associated with “smelly” night lunch wagons whose customers ate them standing on the street, hamburgers were disdained by those of higher means. It didn’t help that in some cases the ground meat was questionable in quality and had been dosed with preservatives. It may have been young people who changed the equation, boosting hamburgers’ popularity in the 1920s.

Meat and potatoes – The popularity of restaurant meals containing both components was intense in the 19th and 20th centuries. The mutton of the 19th century vanished but the love of beef seemed eternal. This was the bedrock American diet, especially popular with men who patronized steak houses. It was not challenged until the 1970s, mostly for health reasons, and yet did not disappear.

Onion rings – Once Americans got over their aversion to onions — mostly in the 1970s when fast food outlets began to offer them — they decided they really loved those deep fried treats! It helped a lot that they had become available frozen and breaded, relieving kitchen workers from having to handle the smelly vegetables.

Pancakes and waffles – Pancakes had long been short order staples, growing in popularity in the Depression as an inexpensive, yet filling, menu choice. Later, the proliferation of chains specializing in pancakes made them popular for all meals, not just breakfast, and attracted the family trade. Waffles have probably been less popular than pancakes overall, but in some ways they proved more versatile since they could serve as a base for other foods, especially fried chicken.

Parsley – Some people eat it, but its main role in restaurants has been decorative. Better yet, it has filled in empty spaces on plates. Its use as a garnish departed from the European practice of matching garnishes with foods whose taste and texture they enhanced. In this country, parsley could appear on any plate regardless of what was being served. Nevertheless, its mere presence signals to the diner that s/he is eating away from home.

Pizza – In its early years it was known mainly to Italian-Americans, but it came into the mainstream in the 1950s, though still relatively unknown in some areas of the country such as the South. For a time it was regarded as a snack more than as a meal. Partly due to the growth of nationwide chains, it would eventually surpass hamburgers in popularity. Cities vie for pizza fame, among them New Haven CT, home of .

Salad – Salads tended to be reserved for elites in the 19th century, but in the 1910s they reached a wider slice of Americans in small French and Italian cafes. As the century progressed salad moved into the mainstream, popularized by salad bars. Meanwhile Caesar salads migrated northward from Mexico into California, while some other parts of the country enjoyed the unfortunately named “wop” salads.

Shrimp – Although hotels included shrimp salad on their menus in the later 19th century, the little crustaceans didn’t achieve notable attention until the rise of shrimp cocktails in the 20th century. Next came breaded deep-fried shrimp, their use boosted by frozen products marketed to restaurants.

Spaghetti – The early non-Italian fans of Italian restaurants featuring spaghetti dinners were drawn by their semi-forbidden attractions, namely red wine and garlic, plus the fun of wrangling spaghetti. In other words, precisely those things that made upright Americans uncomfortable. Artists and musicians, considered “bohemians,” boosted its popularity.

Sugar – Largely absent on restaurant tables today, sugar was once demanded by restaurant customers. Over time the unsanitary sugar bowl, often shared with strangers, was replaced with shakers and then individual paper packets. Wartime restrictions posed a vexing issue for proprietors, as did the behavior of some customers who employed ingenious methods to make off with the scarce commodity.

Surf ‘n’ turf – Brought to this country via airplane in the 1930s, South African “rock lobster” introduced a new menu selection that was destined to achieve fame. The inexpensive lobster tails paired with steak became popular in the 1960s, remaining a favorite into the 1970s. Price increases by the late 1970s were no doubt responsible for the once-inexpensive combo’s decline.

Tomato juice – Introduced to restaurants in the 20th century, tomato juice was once a trendy drink that could serve as an appetizer. Unsurprisingly, its menu appellation, Tomato Juice Cocktail, reflected its popularity during Prohibition. It was sometimes presented in special concoctions – with cottage cheese stirred in, or perhaps orange or clam juice.

Water – It seems that diners were first served a glass of water with their meal in the 1840s when some large cities, including Boston and New York, acquired reservoirs. The new custom pleased temperance advocates, but some newcomers, Italians for instance, preferred wine with their meals. Though many Americans don’t drink the water provided in restaurants, they tend to want it poured for them anyway.

February 18, 2024

A tough business in a tough town

Most people realize that the expense and hassle of opening a restaurant in New York City is daunting, but a 1980 New York Magazine story by Paul Tharp laid it out in excruciating detail.

Generally new restaurants have a short run, but the piece underscored this observation by noting that the city’s Restaurant Association claimed that three of every four places shut down or had new owners within five years. Tharp added that a real estate broker said that one out of ten operating restaurants was for sale “at any given time.”

New York was a particularly tough city for restaurant operators. Higher food costs there meant that the consumer was going to pay four times the cost of a meal’s raw materials rather than three times, then the national norm.

Expenses involved in opening a new restaurant were staggering. Although the total estimate for a 40-seat restaurant of $162,018 given in the article seems quite low by today’s standards, it wasn’t then. The biggest chunks of money were for payroll, kitchen equipment, rent, and remodeling costs.

But that was just the monetary total. Tharp also outlined a time factor, noting that the amount of time spent getting set up was often not anticipated by those lacking previous experience.

The article observed that few new owners expected to be putting in 14-hour days the first year working in the kitchen or waiting on tables, virtually abandoning their personal life. Nor did they realize how much time and patience would be required to obtain licenses and satisfy city regulations, such as taking and passing a 15-hour Health Department course in sanitation and food handling.

And then there were the exasperating bureaucratic hurdles. For some it was a surprise that stove vents were required to extend to the top of buildings. If the Buildings Department found that the restaurant had not obtained a permit and met city standards for remodeling, an owner might need to tear out all the work that had already been done and start over.

Taking over an existing restaurant may have avoided the hassles of remodeling, but its costs were likely much higher and brought their own hazards. Tharp relates a horror story involving two inexperienced men, elsewhere termed “babes in the gastronomic woods,” who wanted to take over a former Toots Shor restaurant for a bargain price if the new owners also assumed the restaurant’s debt. They teamed with major investors who pulled out and left them at sea. They renamed it Jimmy’s after soon-to-vanish partner Jimmy Breslin. Although at first it was quite popular, business then fell off with the recession and they realized they couldn’t handle the large staff or deal with unexpected costs such as credit card service charges, electricity rate hikes, and a temporary loss of their liquor license. Even adding an upstairs cabaret and a downstairs jazz club and hiring Jack Lemmon as Monday night bartender failed to attract the disappearing crowds. After about 34 months capped by a flooded basement, Jimmy’s shut down.

If Tharp’s report didn’t contain enough warnings, a published letter from a Manhattan realtor added another note of caution. He pointed out that owners of “quality buildings,” fearful of restaurant failure rates, tacked on security deposits equal to as much as five months rent, plus additional payments to make up for premiums required by insurers who assessed a higher fire risk for a restaurant tenant. Altogether, he estimated the operating budget should be 30% to 40% higher than Tharp’s.

Perhaps to offset all the bad news, the story included five thumbnail sketches of restaurateurs who overcame obstacles. I took a closer look at their subsequent careers, which raised some questions about just how well they all did. Three seemed to be well-connected pros who, despite disappointments with some ventures, did well overall. One of those briefly profiled was Peter Aschkenasy who had a number of successes including Charley O’s and U.S. Steakhouse, but who hit a snag trying to revive the classic New York restaurant Lüchow’s [pictured at top].

One restaurateur had a place I could find absolutely no trace of anywhere, and another had a single tiny restaurant with a short life. It was operated by the only woman mentioned in the story, chef Leslie Revsin, whose professional biographies unfailingly cited that she was the first woman chef to be hired by the Waldorf-Astoria. She opened Restaurant Leslie in Greenwich Village in 1979. With only nine tables and no liquor or wine license, it lasted only a few years despite critical praise. Following that she cycled through about nine New York restaurant kitchens including Argenteuil, One Fifth Avenue, and The Inn at Pound Ridge, often as executive chef. Eventually she turned to writing cook books.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

February 4, 2024

Dining dangerously

It seems pretty certain that restaurants of the 19th century were far less sanitary than they are today, and that employee hygiene, though still a factor now, was far worse. There were few mechanical dishwashers, no electrical refrigeration, and little understanding of the dangers of foodborne illnesses.

It wasn’t until the 1880s that science threw a spotlight on the subject and the concept of “ptomaine poisoning” developed, identified as alkaline substances formed during animal decomposition. The term ptomaine continued in use in the popular media even into the late 1970s, despite being scientifically questioned for decades and totally discredited by the 1930s. Scientific authorities pointed out that although ptomaines were real, meat would need to be in such an advanced state of decomposition at that point that no human, no animal, would touch it.

Soon after the ptomaine theory of illness was introduced in the 1880s, newspapers began reporting on its victims, many of them restaurant goers. For example, in 1899 the San Francisco Chronicle produced a story about a man who experienced cramps, vomiting, headache, and dizziness two hours after eating ham in a restaurant. A doctor said he had suffered ptomaine poisoning.

Given the documented history of food adulteration, it’s certainly believable that bad meat was often knowingly served in cheap restaurants. Some patrons believed they had been served decomposing meat that was smothered in sauce to hide it. Americans were generally averse to sauces, and whether it was due to fear of poisoning or the sense they were “foreign” is a good question. Probably both.

Eggs also fell under suspicion. Advice given to women shoppers by Harper’s Bazaar magazine in 1896 seems wise. It observed that “One hears of more sick results from salads than any other dish.” Salad at that time did not typically refer to vegetable salad but rather to chicken or other meat salads dressed with mayonnaise. In these cases it was likely that eggs used in mayonnaise caused Salmonellosis. The article recommended ordering “something hot, and better still if it is cooked for you,” which was reasonable advice.

What may have limited the overall incidence of foodborne illness in the 19th century was simply that then fewer people ate in restaurants, most restaurants were small and served few meals, and food production was smaller in scale and more localized so that the reach of contaminated food was reduced. Of course, since symptoms of foodborne illnesses don’t show up until between 10 hours to days later, it was unlikely then, as now, that most were identified or reported as such.

The association of sickness with restaurants began to play on the public’s imagination in the early 20th century. In summer 1908 a lunchroom waiter offered his thoughts: “If you must eat meat [in] this hot weather, select anything but hash or a Brunswick stew. If you insist on a finger bowl, have the man who serves you fill it in your presence. If you drink water at meals, make a private arrangement with your waiter. And if you must have buttered toast with your breakfast, don’t read this story.”

No doubt the waiter’s warnings were correct. A 1929 article in Restaurant Management magazine claimed that 25 years earlier few restaurants could have met modern sanitary regulations. The author said that most used lard cans for cooking, had no dishwashing machines and kitchens full of flies. Most also saved scraps from customers’ plates, left them sitting out for hours, and served them a second time – which explains why customers were suspicious of hash and stews.

As of 1925 the biggest known outbreaks of foodborne illness in the U.S., with the most fatalities, resulted from typhoid-infected oysters from polluted Long Island waters. The problem was not uncommon in the early 20th century, and caused a drop in oyster consumption. Yet in 1925 outbreaks sickened more than 1,500 people in New York, Chicago, and Washington D.C., with 150 deaths. There is no report of how many of those afflicted ate the oysters in restaurants, but it’s likely most did.

Generally, tracing reported cases to their source has always been quite difficult and most are not reported at all. Victims often think they have the mythical “24-hour flu.” Or they might attribute their distress to the last meal they ate in a restaurant when the source could well have been something consumed days earlier. In the case of Campylobacter, it has been estimated that as many as 2M people are afflicted each year (though not solely from restaurant meals), leading to more than 10,000 hospitalizations. Salmonella may afflict somewhat fewer people but causes more hospitalizations and deaths. [Above: 1989 cartoon still using the term “ptomaine”]

If restaurants seem to loom large in food poisoning history, that is at least partly explained by the greater ease in identifying cases when there is an outbreak where a group of people have eaten the same thing.

In more recent decades restaurant outbreaks have received quite a bit of public attention. And, although restaurants are cleaner and more careful than in the past, food perils have not gone away. In fact pathogens recognized after 1990 such as E. coli O157:H7, Listeria, and Campylobacter are some of the most dangerous. And it is not just protein food that is risky, but also fresh produce that has been contaminated by exposure to infected animals or water.

Norovirus is the most common variety of foodborne illness, and is found in fruits and vegetables and oysters. Its symptoms are flu-like, and, unlike bacterial agents, its spread is aided by transmission from infected persons, particularly in close environments such as cruise ships.

As news of outbreaks goes, it tends to focus on chain restaurants such as McDonald’s, Jack in the Box, Sizzler, Burger King, and others. Often that is less an indicator of their bad practices than it is a result of a massive industrial food processing system they are part of, marked by risky methods of raising animals, long distance transport, and other profitable economies of scale.

In the case of one large supplier, Hudson Foods, outbreaks resulted in a 1997 recall of 25M lbs. of beef patties possibly contaminated with E. coli. As a result as many as a fourth of Burger Kings nationwide had no burgers to sell for up to two days. After Listeria was discovered in its turkey deli meats, processor Pilgrims Pride set a new record in 2002 by recalling 27.4M lbs. of its products that had been distributed to restaurants, food stores, and school cafeterias.

And yet it wasn’t just large suppliers and distributors that were to blame. Outbreaks of E. coli and Salmonella in Chipotle outlets across the county in 2015 were not believed to be linked to large-scale suppliers but to the company’s mission of sourcing fresh food from small, local farmers.

Despite today’s threats, however, it’s probably as safe to eat in restaurants as it is at home.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

January 21, 2024

Building a myth: Bookbinder’s

As a Philadelphia Inquirer story observed when the legendary Bookbinder’s on Walnut Street closed for the first time, in 2002, its popular appeal had been based not only on seafood and steaks but also on the restaurant’s ability to play on its history.

Eventually, in the 1940s, the myth led to a claim that it was founded in 1865. Not everyone took the claim seriously, but that still leaves the question of why the restaurant invented it. The motivation was somewhat mysterious considering that Bookbinder’s was in fact very long-lived compared to most restaurants in the U.S., which do well to last five years. It’s curious to me that the actual founding date in the 1890s wasn’t good enough.

An 1895 newspaper story reported that Cecilia Bookbinder, wife of Samuel, had bought the building on 125 Walnut Street for $5,000. Since 1884, it had been operated as an oyster and chop house by a man named Attila Beyer. It appears, however, that the devious Beyer may not have actually owned the building when he sold it to Cecilia, having already used it as collateral for a loan on which he was about to default as he left for California.

Perhaps due to monetary claims by Beyer’s creditors, the Bookbinders evidently lost ownership of the building and didn’t regain it until 1906, nevertheless operating the restaurant all the while, possibly at first under the simple name Merchant Restaurant. The restaurant was in Philadelphia’s long-established insurance district where business people flooded the local eating places at noon.

Somewhat before the myth of an 1865 founding was adopted, 1875 was advertised as the restaurant’s start date. For instance that was the date given in a 1940 Life Magazine advertisement for Hines ketchup shown here; it is also indicated by the poster on the wall.

A family rift may partially explain the adoption of an exaggerated founding date. Bookbinder’s on Walnut street adopted the name “Old Original Bookbinder’s” about 1935 or 1936 after Samuel C. Bookbinder, son of the founders, opened a rival Bookbinder’s on South 15th Street [shown above, 1935]. He had been in line to inherit the Walnut Street restaurant but was disinherited upon his conversion from Judaism to Catholicism in order to marry a Catholic woman. The false founding date and the name “Old Original” were likely ways to distance the Walnut Street restaurant from its new competitor. [Note that the 1936 advertisement below had not yet revised the fictitious founding date.]

As a result of the family split, Harriet Bookbinder took over the Old Original, operating it with her husband Harmon Blackburn. He was a successful corporate lawyer, and a collector of Americana, including the Lincoln memorabilia, old theater playbills, and Carrier & Ives prints that adorned the restaurant’s walls.

Obviously the building occupied by Old Original Bookbinder’s itself looked aged, and the memorabilia contributed to a sense of age. Other historical attractions were the fireplaces made of old cobblestones taken from Walnut Street. The fireplaces probably dated back to 1915 or 1916 when the city was removing cobblestones from streets. A 1916 advertisement promised “A Beefsteak Dinner in the ‘Maine Woods’” cooked at that room’s fireplace, with steaks and chops grilled in the fireplace and served with oysters, radishes, celery, and hot biscuits baked on the hearth.

When Harriet died in 1944, her husband ran the restaurant for a year and then donated the business to the Federation of Jewish Charities. Along with the building, the furnishings and equipment, the donation included “all food and liquors on hand, the good will and everything in the till.” John and Charles Taxin bought it, with John running it until its final bankruptcy and closure.

In the 1940s and 1950s Old Original Bookbinder’s was regularly recommended in books featuring the country’s favorite restaurants, such as Duncan Hines Adventures in Good Eating. In 1947 “The Dartnell Directory for America’s Most Popular Restaurants named it the country’s most popular eating place of the 2,300 restaurants it recommended.

In 1965 the restaurant celebrated its 100th anniversary as Bookbinder’s — a mere 30 years prematurely.

By the 1970s, the cobblestone fireplaces remained, but some rooms had been redecorated and modernized. Time was catching up with Bookbinder’s then, as new kinds of restaurants with inventive cuisine such as Le Bec-Fin came on the scene. Citing an estimated 300 new restaurants opening in Philadelphia in the early 1970s, a 1978 issue of trade magazine Restaurant Hospitality observed that traditionally conservative Philadelphia was now “vying with New York and San Francisco as the Eating Capital of the United States.”

Nevertheless, in 1986 Restaurant Hospitality rated Old Bookbinders the nation’s 7th highest-grossing restaurant, with annual sales totaling $10.6M and an average dinner check of $33. It was well-known nationwide and particularly popular with tourists, all the more so since it was near historical points of interest.

But nothing lasts forever. Both Bookbinder’s closed in the first decade of the 21st century.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

January 7, 2024

Psychedelic restaurants

The short-lived psychedelic “theme” did not become popular in restaurants to the same degree that it did in the music world. But when you think about it, that’s not too surprising. [Trident menu, ca.1969]

As decor, a psychedelic interior made generous use of strobe lights and brightly colored paint. The decor was most likely to turn up in a teen club or a nightclub, such as Mother’s in San Francisco in 1969. Just reading a one-sentence description of Mother’s interior “with walls that modulate, colors that pulsate to music, hallucinatory lights . . .” is enough to make me queasy. Scarcely an environment for dining!

Interiors were meant to mimic the effects of LSD without the aid of drugs. This makes sense for music clubs, but it’s hard to see what it might lend to a café’s ambience.

Nevertheless there were a scattering of restaurants and cafes throughout the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s that were referred to in the press as being psychedelic in some sense. It was not always clear what that meant other than having psychedelic decor with bright colors or swirls.

The psychedelic Uptown Café in Madison WI, for instance, was decorated with fist-sized rocks “handpainted psychedelically [with] pop swirls.” But surely it took more than that to categorize the café as psychedelic. What that might have been is unknown.

Like the “Uptown Café,” some so-called psychedelic eating places had names that weren’t at all suggestive of grooviness, such as Dino’s in Tampa FL, the Great Society in Minneapolis, and the Feed Store in Chicago. In 1969 the Feed Store was firebombed, with police assuming that the perpetrator was someone in the neighborhood who disliked hippies and their psychedelic decor.

Although the natural food movement emerged at the same time as the interest in exploring consciousness via drugs, it would seem that not all psychedelic restaurants embraced it. Haight-Ashbury’s main gathering spot for the area’s hippies was The Drogstore, so named to avoid the obligation to fill prescriptions. Tabletops there may have featured “psychedelic linoleum” but the menu was centered on ordinary hamburgers, minestrone, and soft drinks.

Other eating places shown on a Haight-Ashbury tourist map of the late 1960s could have been just about anywhere judging from their commonplace designations, such as Mexican Restaurant, Pizza Joint, and Grinder Joint.

Outside of San Francisco, the 1969 Temptations’ hit pop song Psychedelic Shack inspired several places to adopt that name, one in Belle Glades FL and another in Salt Lake City. Like so many psychedelically inspired eating places and clubs, they were aimed at young people.

A bit later, after the Haight-Ashbury scene had dispersed, mainstream commerce discovered psychedelics – and it was odd. Burger King’s “Love” postcards and Mattel’s Barbie embraced a watered-down version evidently acceptable to the majority of Americans in a way that hippies were not. The “vibe” was detached from all meaning other than swirling color and made its appearance slightly after the movement had lost its center in San Francisco. Yet it was undoubtedly an attempt to appeal to teens. Burger King gave away its postcards for patrons to send on Valentines Day, 1972.

The best known psychedelic restaurant was Sausalito’s Trident, owned for a number of years by the Kingston Trio. It had a swirling ceiling and wild-looking menus. The early menu shown above listed natural foods but later ones featured many conventional items such as steak, plus alcoholic beverages said to be generally rejected by hippies. By 1970 it had become a favorite of tourists, and reportedly entertained “the hip and many society names trying to be hip.”

The Trident’s early menus were filled with cosmic advice in tiny type, dispensing such pseudo wisdom as “One must rise by that which one falls,” and “You can’t know what is in if you’re never off.” However, the messages at the menu’s bottom brought the patron back to earth with a thud, advising, “Sorry we do not accept checks,” and “When necessary, table service minimum of $3 per person.” [Click to see later Trident menus]

Nonetheless, another message from the Trident menu contains a wish for 2024: “May all our offerings please you. Peace within you.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

December 19, 2023

Christmases past

Christmas, like Thanksgiving, is hard to write about on a blog about restaurants. I’ve tried my best to imagine topics over the years. This is the year to take a break and recycle them! The oldest one goes back to 2009, but it’s as good as ever. [above: the Log Cabin, Holyoke MA, as it once was]

Christmas Feasting

Saddle of antelope for Christmas? Not for me. Couldn’t Santa use antelope to pull his sleigh in a pinch?

Christmas dinner in a restaurant again?

A person could do a lot worse than having dinner at Conway’s Bon Ton in 1891. Only 25 cents, with 6 roasts and deserts galore.

Holiday banquets for the newsies

The newsboys had a hard life and this was the one day of the year they could celebrate – and get enough to eat!

Christmas dinner in the desert

Who would choose to celebrate Christmas at a restaurant in the desert called the Christmas Tree Inn? Actually, I don’t know the answer to that.

Chinese for Christmas

Chinese restaurant owners in New York City were eager to please their Jewish customers, so much so that at least one was kosher as early as 1907.

Dinner in Miami

Were there more restaurants serving Christmas dinner in Miami than in most cities? Maybe so.

I am wishing for happy holidays for all of my wonderful readers!

December 3, 2023

Black-owned drive-ins

Despite the documentary absence of postcards, I’ve discovered that there were others — after a lot of searching. And I’m glad, because in nostalgic American culture, drive-ins are seen as deeply and exclusively white.

Most I’ve located got their start in the 1940s and 1950s, the same years that white-owned drive-ins made their first appearance many places, particularly warmer climates. More people in those years, especially after WWII, had cars and a little extra money to spend. [Highlight Grill, Greenville MS, 1952]

The earliest reference I’ve found was to The Drag, on Lyons Avenue in Houston. In an advertisement for its sale in 1941 it was described as a “famous colored drive-in.”

Black drive-ins were most likely to be found in Southern cities before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made Jim Crow segregation illegal and all public restaurants had to serve everyone regardless of race. Although they could be found in Northern cities, it seems they were more likely to be in good-sized Southern cities such as Chattanooga, Memphis, and Nashville TN, Louisville KY, Little Rock AK, and Birmingham and Tuscaloosa AL.

Altogether I’ve run across 54 Black-owned drive-ins in this country, which is not many but surely an undercount. I have not found any in the Northeast. Nor in the land of drive-ins, Southern California, where they dated back to the 1930s. No doubt there were some, but probably fewer than elsewhere.

It was mainly in the 1960s that they began to show up in the yearly Green Books that advised Black travelers on places to stay, eat, fill up with gas, etc., in unwelcoming parts of the U.S. – i.e., most of it. (I cannot be 100% certain that every drive-in listed in the Green Books had a Black owner since sometimes white-owned restaurants that welcomed Black customers were also listed.) [Shown here, a Green Book advertisement from the 1961 edition.]

Many, maybe most, of the drive-ins served barbeque. For example, Nichol’s Drive-In in East St. Louis IL specialized in hickory-smoked Beef Ribs, Snoots, Pork and Chicken. It mentioned Soft Drinks, but a number of Black drive-ins served beer. Selling beer to underage customers seemed to get some of them into trouble.

I noticed that when a new Black-owned drive-in opened, it was usually greeted with enthusiasm in Black newspapers. White newspapers, on the other hand, often only reported on them in association with disorderly incidents and legal violations.

When a Black-owned drive-in was proposed for a location near a white residential area, it was unlikely the plan would be approved. (The same held true for Black-owned drive-in movie theaters.) In 1951 a Black man seeking official approval to build a drive-in restaurant in Memphis faced a hostile lawyer representing whites who opposed it. The opposition’s lawyer referred to the drive-in as a “Negro night club,” and when the applicant’s lawyer objected, maintained that a drive-in was “the same thing.”

The drive-ins that seemed to fare the best were those owned and run by prominent figures in Black communities. In the 1940s Little Rock’s Nou Vean Drive In was owned by Barnett G. Mays, a realtor, developer, and liquor store owner. He encountered numerous roadblocks throughout his business career, but seemed to press onward despite them. In Milwaukee a drive-in called Robbys appeared to have a promising future when it opened in the late 1960s. It was named after the son of owner J. C. Thomas, a community leader who was also a realtor, operated two billiard parlors named Ebony Cue, and published a newspaper called Soul City Times. [Above: Nou Vean, 1945; Below, Robbys 1969]

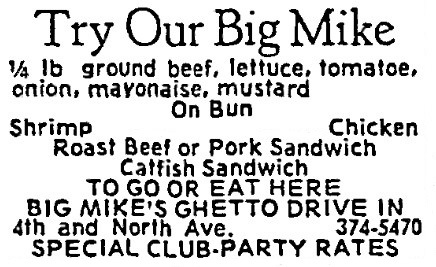

However, drive-ins generally – both Black and white – met major competition in the late 1960s when fast-food chain restaurants spread across the country. In Milwaukee Robby’s as well as Big Mike’s Ghetto Drive-In faced off with national chains and lost.

Big Mike’s owner Mike Watley, a social activist and close associate of comedian Dick Gregory, explained that he could not compete with a national corporation. With lower sales volume, he paid higher prices for food, a situation intensified by being given less financial support. His meat supplier, he said, capped his credit at $100, while white customers could run up their bill to three or four thousand. Although Watley blamed his failure on competition from a “white-owned corporation,” the nearby McDonald’s franchise was owned by two Black men, one of them Wayne Embry, a former player with the Milwaukee Bucks. Their McDonald’s venture was quite successful. [Above: Big Mike’s, Milwaukee, 1969; Below: Wayne Embry, left, and his partner, 1971]

Independent Black-owned drive-ins have not totally disappeared, however. In Longview TX White’s Drive-In, established in 1952 in conjunction with the White’s motel, has recently been re-opened by younger members of the family.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

November 21, 2023

Thanksgiving, turkey, restaurants

These are older posts, but still as good as ever! I mean, how much can you write about Thanksgiving and restaurants – or about turkey? Well I managed to turn out seven that are decent enough for a rerun. Here they are, in chronological order. [Victorian trade card, 1878]

Restaurant-ing on Thanksgiving

Is eating Thanksgiving dinner in a restaurant a “rather melancholic thing”? Does the menu tend toward “baby food”?

A Thanksgiving Toast

Why we should toast workers in Chinese restaurants on Thanksgiving day.

Thanksgiving quiz

I present you with four dummied up, but real, menus listing complete dinners that were presented at a Kalamazoo café in 1921 and you figure out which was the most expensive. The answer is given in the comments.

Cooking up Thanksgiving

Beginning as a Yankee holiday and retaining that association for decades, the holiday spread slowly. The story on restaurants is simply that it wasn’t at all common for restaurants to recognize the holiday in the 19th century and well into the 20th. It also took a while before all Americans, particularly immigrants, decided the day was meaningful for them.

Turkey on the menu

This one is focused less on the holiday and more on the leading dish. How has turkey fared in restaurants generally? Did luxury restaurants include it on their menus?

Turkey burgers

Another one focused on the bird and the restaurant industry’s attempts to get customers to accept it. Lo, the turkey burger!

Thanksgiving dinner at a hotel

Wealthy members of the Sons of New England showed a preference for goose and plenty of alcoholic beverages at a hotel dinner on Thanksgiving in 1817. Another group of men from Massachusetts, celebrating in 1843, enjoyed a side of baked beans, finishing with a bowl of molasses that made the rounds so they could all get a lick.

Wishing you all a happy holiday!

November 12, 2023

Chicken in the Rough

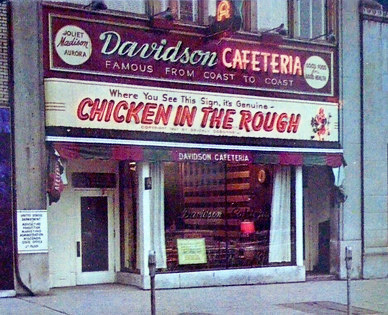

Frequently when I write about the demise of a restaurant chain I can almost be certain to hear from at least one person who lets me know there is a survivor of that long-gone chain.

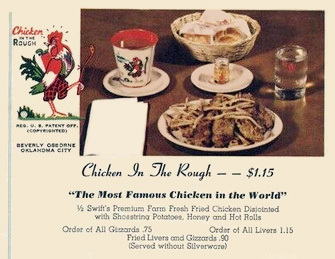

And, yes, that is also true of Chicken in the Rough, a franchised process for preparing fried chicken. As recently as now, Palms Krystal Bar & Restaurant in Port Huron MI offers “The World’s Most Famous Chicken Dish,” as it has for decades. In 2000 a Palms order consisted of an unjointed half fried chicken, with shoestring potatoes, hot bun, and jug of honey. Two orders cost $9.99 and they even threw in free coleslaw. In the 1930s an order usually was priced at 50 cents. [above, 1940s menu from an Arkansas restaurant]

The developers of the Chicken in the Rough formula were a husband and wife team, Beverly and Ruby Osborne. They ran roughly nine cafes and waffle shops in Oklahoma City and even the 1930s Depression could not halt their enterprising spirit. [above: Beverly Osborne pictured in yellow boots]

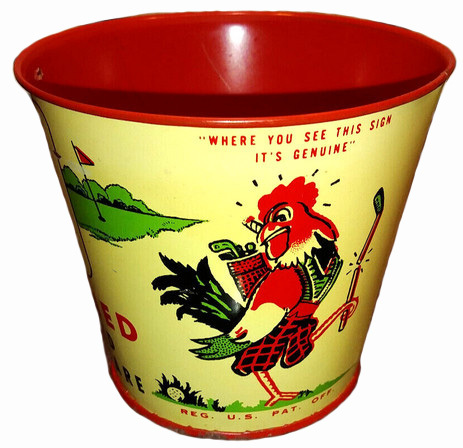

Their operations employed the magic word in modern management of that time – “system” – to streamline their operations and reduce costs. In 1936 they opened a drive-in in Oklahoma City which introduced customers to their method of preparing chicken. They soon began franchising the process and the trademark. In 1942, they patented their imprinted dishware and glasses, and the image of a chicken with a broken golf club, all of which had been in use for several years.

“In the Rough” was a perplexing phrase that often needed an explanation. It meant no silverware was provided despite the half chicken being unjointed. Evidently customers proved willing to adapt to “roughness,” although I’ve run across some evidence that over time some franchisees served the chicken in pieces. Another alternative was to serve the meal with a small metal pail filled with water for cleaning hands.

When the Osbornes opened the Ranch Room at their Oklahoma City drive-in in 1937 a large advertisement appeared in The Daily Oklahoman. Just in case anyone reading it didn’t realize the name Chicken in the Rough had been copyrighted, they were informed of this six times in the text: Yes Sir, “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – In one year we are known from coast to coast for “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – Served without silverware. In one year we have sold over 50,000 chickens or 100,000 orders of “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – We are now able to offer for sale franchises on “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) . . . We took the town by storm – “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) 50c. [Above: Madison WI franchisee]

The Osbornes were very particular about the meal’s composition, preparation, and presentation. Franchisees were required to use a freshly killed chicken, weighing 2 pounds and graded A, meaning it had been raised in an incubator and had sustained no injuries. No batter could be added to falsely make it look bigger and it had to be cooked in vegetable oil that had not been used for any other purpose. Inspectors came by regularly to make sure franchisees were following the rules.

World champion runner Jesse Owens, winner of four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics, was slated to open a restaurant featuring Chicken in the Rough in Chicago in 1953, for which he planned to use delivery wagons decorated with large images of himself racing. I could not determine the fate of that plan, but I don’t think it ever materialized.

The Osbornes sold the rights to their franchised process in 1969 and ten years later ownership changed hands once again. At the time of the first sale of the business there were only 68 franchises in 20 states left, compared to possibly 379 in 38 states at the peak, which I am guessing was in the late 1940s. Judging from a 1946 postcard that claimed to list all the U.S. restaurants with franchises then, most of the populous states without franchisees were in the Northeast. By contrast, Michigan had the most, followed by Indiana and California.

Unlike that of Harlan Sanders, who also began by selling a chicken recipe across the U.S. some years after the Osbornes, their venture remained a franchised cooking process and did not develop into a chain of restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023