Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 40

February 9, 2013

Celebrity restaurateurs: Pat Boone

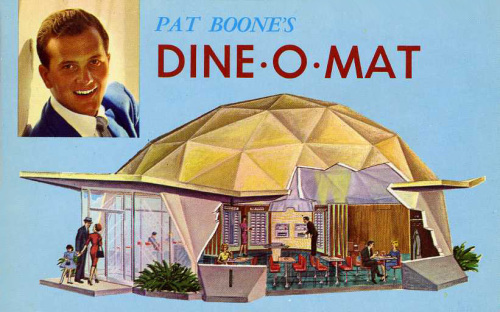

Few celebrities become deeply involved in the restaurants that bear their names. That was true of the singer Pat Boone, who was known to visit his namesake restaurants occasionally and to sing and sign autographs at openings. How much good his – or any celebrity’s – connection does for a restaurant is debatable. Neither Pat Boone’s success as a performer nor his pro-family, clean-cut, Christian image saved the ventures he lent his name and money to.

Pat Boone’s Dine-O-Mat appears to have barely gotten off the ground despite what publicity referred to as its “space age” design. “This . . . new type of fully automatic roadside restaurant is destined to be an important landmark on highways all over America,” boasted a 1963 advertisement aimed at investors. The initial plan was to build 100 of the restaurants by summer of 1964, but few seem to have been constructed.

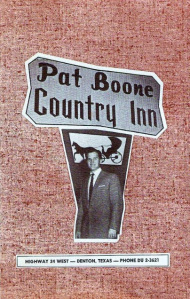

An earlier disappointing experiment in restauranting, Pat Boone’s Country Inn, in Denton TX, closed a mere four years after opening in 1958, even though Boone was connected to the town because of attending North Texas State College there.

An earlier disappointing experiment in restauranting, Pat Boone’s Country Inn, in Denton TX, closed a mere four years after opening in 1958, even though Boone was connected to the town because of attending North Texas State College there.

While the Country Inn was a conventional restaurant, Dine-O-Mats were designed to be “revolutionary.” Perhaps the New Jersey entrepreneurs who cooked up the Dine-O-Mat concept were inspired by Stouffer’s 1961 foray into selling frozen food from vending machines to Ohio turnpike motorists who reheated it in microwave ovens.

Little could Pat Boone and company know when they launched Dine-O-Mats in 1962 that Stouffer’s would announce less than a year later their intention to phase out the roadside restaurants after realizing that travelers only wanted “speed and price.”

Both Stouffer’s highway restaurants and Dine-O-Mats might be called automats. But unlike Horn & Hardart automats, coins put in a slot did not call forth ready-to-eat selections. Dine-O-Mats had only one employee on the premises, an attendant whose job was to keep the machines loaded with frozen food. Rather comically, the postcard above shows customers (and Pat) dressed in their Sunday best, yet they are “dining” in a dismal geodesic-domed hut surrounded by vending machines and two microwaves sunk into an imitation hearth.

Similar to Stouffer’s restaurants, Dine-O-Mats were to be located near “motels, service stations, shopping centers, bowling alleys, country clubs, amusement parks, factories, air and bus terminals and along major highways,” according to a 1962 prospectus. How many were ever built, other than the prototype on Route 46 in Little Ferry NJ, is unclear. There may have been a few additional ones in New Jersey and Georgia.

Since kitchenless Dine-O-Mats relied on cooked food supplied by an offsite commissary, the scheme made sense only if deliveries could reach multiple outlets easily. In 1964 construction was to begin on a unit in Augusta, Georgia, but the project was delayed because of company “reorganization.” It was to be part of a group of Dine-O-Mats in Albany, Macon, and Savannah, but whether any of the Georgia restaurants opened I cannot determine.

In 1965, when the Augusta construction was slated to begin, a newspaper report announced, “The Pat Boone Restaurant Corp. has revised all plans and has just now completed reorganization with new, modernized plans for its restaurants.” Though it’s hard to imagine what could be more modern than “space age,” it’s possible the geodesic dome had been scrapped and that the North Plainfield NJ Dunkin Donuts pictured here was once a Dine-O-Mat as some people believe.

In 1965, when the Augusta construction was slated to begin, a newspaper report announced, “The Pat Boone Restaurant Corp. has revised all plans and has just now completed reorganization with new, modernized plans for its restaurants.” Though it’s hard to imagine what could be more modern than “space age,” it’s possible the geodesic dome had been scrapped and that the North Plainfield NJ Dunkin Donuts pictured here was once a Dine-O-Mat as some people believe.

The company’s confusing advertisements for prospective investors required differing minimum investment amounts ranging from $2,500 to $10,000 for a “limited (inactive) partnership” in April of 1963, to $15,000 to become an “area controller” in October, then asking $10,000 for an “investment opportunity” in March of 1965. Did anyone ever get the 10% to 13% returns that were estimated?

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

February 2, 2013

Diary of an unhappy restaurateur

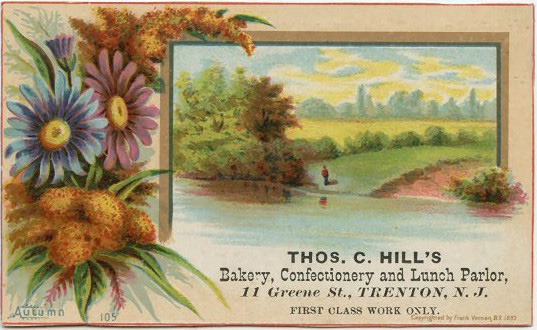

Edmund Hill began working in his father’s bakery and restaurant full-time in 1873 when he was 18. His help was needed because of his father’s poor health. He wanted to go on to Yale, yet he devoted his career to the business, which was operated under his father’s name Thomas C. Hill.

Edmund Hill began working in his father’s bakery and restaurant full-time in 1873 when he was 18. His help was needed because of his father’s poor health. He wanted to go on to Yale, yet he devoted his career to the business, which was operated under his father’s name Thomas C. Hill.

Thomas Hill founded the business in 1860, rapidly becoming one of the city’s leading caterers and furnishing everything needed for soirees, suppers, and weddings except, as a 1866 newspaper story remarked, the brides and bridegrooms. Located in the center of Trenton, New Jersey, the restaurant advertised in 1882 that it was “the largest and finest between New York and Philadelphia” and could provide in its dining rooms or beyond all the fancy dishes of the day: boned turkeys, croquettes, rissoles, jellied meats, carved ice blocks, charlottes, spun sugar centerpieces, and bon bons. Hill’s hosted many organizations at its Greene Street location, including the Young Men’s Gymnastic Association whose members stuffed themselves in 1883 with many of the above plus a variety of ice creams, meringues, and walnut kisses. He specialized in fancy desserts, as is demonstrated by a portion of an 1883 souvenir menu shown here (courtesy of Henry Voight — The American Menu).

Thomas Hill founded the business in 1860, rapidly becoming one of the city’s leading caterers and furnishing everything needed for soirees, suppers, and weddings except, as a 1866 newspaper story remarked, the brides and bridegrooms. Located in the center of Trenton, New Jersey, the restaurant advertised in 1882 that it was “the largest and finest between New York and Philadelphia” and could provide in its dining rooms or beyond all the fancy dishes of the day: boned turkeys, croquettes, rissoles, jellied meats, carved ice blocks, charlottes, spun sugar centerpieces, and bon bons. Hill’s hosted many organizations at its Greene Street location, including the Young Men’s Gymnastic Association whose members stuffed themselves in 1883 with many of the above plus a variety of ice creams, meringues, and walnut kisses. He specialized in fancy desserts, as is demonstrated by a portion of an 1883 souvenir menu shown here (courtesy of Henry Voight — The American Menu).

Edmund’s diary from 1876 through 1885 has been transcribed and digitized by the Trenton Historical Society and makes fascinating reading. Among other things it gives rare glimpses into the running of a bakery/restaurant/confectionery/catering business in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Edmund was a reluctant restaurateur. As the Historical Society’s site says, “Edmund severely disliked, even hated, working in the restaurant business and he focused much of his energies elsewhere, such as pursuing real estate and civic affair concerns throughout Trenton.”

Edmund’s diary from 1876 through 1885 has been transcribed and digitized by the Trenton Historical Society and makes fascinating reading. Among other things it gives rare glimpses into the running of a bakery/restaurant/confectionery/catering business in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Edmund was a reluctant restaurateur. As the Historical Society’s site says, “Edmund severely disliked, even hated, working in the restaurant business and he focused much of his energies elsewhere, such as pursuing real estate and civic affair concerns throughout Trenton.”

Despite Edmund’s lifelong disappointment over being forced to take up a trade, he ran a successful business which he diligently kept abreast with the progress of the times, remodeling the restaurant, increasing baking capacity, and installing electricity. In the 1880s Hill’s restaurant and catering service, almost certainly run on a temperance basis, was known throughout New Jersey. And it made money as his diary entry of December 31, 1881, shows: “Finished up accounts in store. We took in $18,146.60, against $15,294.40 last year. Very satisfactory all around.”

Edmund became an expert cake baker and could, and did, fill in for just about any employee. In 1880 he paid his German baker to teach him how to make the Vienna bread made popular by the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. (“Bargained with Karl to teach me baking for twenty five dollars.”) On at least two occasions he organized a series of public cooking lessons taught in Trenton by cookbook author Maria Parloa of New York. In his diary he wrote that he found her lecture on bass with tartar sauce, baked fish with hollandaise sauce, ginger bread and vegetables “very instructive.”

When he traveled to New York City or other cities he often ate at leading restaurants and probably toured their facilities. He mentions going to Dorlon’s, the renowned oyster restaurant in Fulton Market as well as Delmonico’s, the Hotel Bellevue, the Astor House, and the Vienna Model Bakery, all in NYC. He went to Moretti’s – Charles Delmonico’s favorite place for ravioli – but evidently did not care for it. (“Do not like Italian cooking.”) He even attended the French Cooks Ball to check out the fare. (“Dresses and dancing were ridiculous. The tables were superb.”)

When he traveled to New York City or other cities he often ate at leading restaurants and probably toured their facilities. He mentions going to Dorlon’s, the renowned oyster restaurant in Fulton Market as well as Delmonico’s, the Hotel Bellevue, the Astor House, and the Vienna Model Bakery, all in NYC. He went to Moretti’s – Charles Delmonico’s favorite place for ravioli – but evidently did not care for it. (“Do not like Italian cooking.”) He even attended the French Cooks Ball to check out the fare. (“Dresses and dancing were ridiculous. The tables were superb.”)

In addition to ensuring the reputation of Hill’s Restaurant and Bakery, he was a well-off, well-read man of the world who traveled to Europe several times, a successful real estate developer, a banker, a city councilman, an esteemed civic benefactor, as well as a devoutly religious family man. He was friends with famous people, including Leo Tolstoy, whose son he hosted at an honorary dinner at Delmonico’s. Yet, according to the Historical Society’s site, he never got over having to end his education to take over the family business and considered himself a failure.

He sold the restaurant building and all his catering equipment in 1905 while moving the bakery which continued in business for many years thereafter.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

January 26, 2013

Basic fare: bread

Bread has always been basic to restaurants ranging from the lowliest hash house to the most elegant French dining room. This was made evident in 1912, for instance, when Los Angeles drafted a city ordinance permitting no liquor to be served without meals. The ordinance defined a meal as “not costing less than 15 cents, to consist of bread, or equivalent, together with meat, fish, cheese or beans in sufficient quantity to go beyond the question of subterfuge for a meal.”

Bread has always been basic to restaurants ranging from the lowliest hash house to the most elegant French dining room. This was made evident in 1912, for instance, when Los Angeles drafted a city ordinance permitting no liquor to be served without meals. The ordinance defined a meal as “not costing less than 15 cents, to consist of bread, or equivalent, together with meat, fish, cheese or beans in sufficient quantity to go beyond the question of subterfuge for a meal.”

From the early decades of the 19th century, bread not only accompanied almost every meal, in many cases it was the meal. The most fundamental early eating house meal was bread and coffee or bread and hot milk. When ordering the typical cheap meal of a thin slice of meat accompanied by some potatoes, customers were consoled by the fact that their meal would be filled out with two slices of bread.

In addition to brown bread, i.e., whole wheat bread, restaurant customers could hope for other varieties to pair with their coffee. Waffles and pancakes tended to be classified as breads in those days. In San Francisco in 1858, the Empire State Dining Saloon also served “Mississippi Hot Corn Bread, Hot English Muffins, Hot American Waffles, Hot Hungarian Rolls, Boston Cream Toast, German Bread, and New York Batter Cakes.” After Vienna-style yeast bread was introduced at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, restaurants associated with bakeries scrambled to hire bakers who could produce this newest sensation.

In order to get their free bread, diners had to order something costing at least 10 cents, as recounted in the comical tale of the hapless diner who asked for bread with a too-small order. The amount of bread given with an order was limited. An 1849 bill of fare from Sweeny’s House of Refreshment in New York City shows 3 cents was the going rate for extra bread.

Bread – and butter – were often poor or deliberately adulterated in the 19th and early 20th centuries, so many eating places advertised that they observed quality standards. In the 1880s, cooking teacher Jessup Whitehead almost went apoplectic about the poor quality of baking-powder biscuits often found in low-priced restaurants. He wrote:

Bread – and butter – were often poor or deliberately adulterated in the 19th and early 20th centuries, so many eating places advertised that they observed quality standards. In the 1880s, cooking teacher Jessup Whitehead almost went apoplectic about the poor quality of baking-powder biscuits often found in low-priced restaurants. He wrote:

Such biscuits are yellow, dirty on the bottom, greasy to the touch; they have rough sides, no edges, for they rise tall and narrowing towards the top; they are wrinkled and freckled and ugly; they will not part into white and eatable flakes or slices, but tumble in brittle crumbs from the fingers, and eat like smoked sawdust.

Even today it is commonplace to form a quick judgment about a restaurant by the quality of its bread. Historically patrons probably fared best if they went to a bakery restaurant that made its own baked goods. Or to a tea room in the early 20th century, many of which made a specialty of raisin, nut, or gingerbread, preferably served hot from the oven. In tea rooms, however, patrons often paid dearly for bread and rolls, usually on an a la carte basis.

Even today it is commonplace to form a quick judgment about a restaurant by the quality of its bread. Historically patrons probably fared best if they went to a bakery restaurant that made its own baked goods. Or to a tea room in the early 20th century, many of which made a specialty of raisin, nut, or gingerbread, preferably served hot from the oven. In tea rooms, however, patrons often paid dearly for bread and rolls, usually on an a la carte basis.

By the turn of the century many habitual restaurant-goers had a habit of eating all the bread as soon as it was placed on the table. Etiquette minders disliked this behavior and owners preferred to serve bread only after other dishes were served. Waiters, on the other hand, liked the bread and butter set up because it enabled them to serve more guests who, with something to nibble on, were less impatient for their orders.

Not all eating places did their own baking even in the 19th century, and the number that did was drastically reduced by the mid-20th. As few as 6% of all restaurants did their own baking by 1952. However, the advent of frozen bread made “Doing our own baking” a common advertising claim in the 1960s. That decade also saw a spread in the novelty of individual loaves of bread served on a carving board, made possible by in part by frozen doughs, loaves, and rolls.

As popular as the “cute” little loaves were for a time, discriminating patrons rejected them as mushy and tasteless. The counterculture preferred heavier whole grain breads, which soon made their way into restaurants such as Sausalito’s Trident. On a ca. 1968 menu, the rather high price charged for a basket of rolls was justified as follows: “Our rolls are hand baked for us daily using only the purest ingredients: finest organic grains, fertile eggs, organically grown onions & raisins, raw butter, oils & honey.”

As popular as the “cute” little loaves were for a time, discriminating patrons rejected them as mushy and tasteless. The counterculture preferred heavier whole grain breads, which soon made their way into restaurants such as Sausalito’s Trident. On a ca. 1968 menu, the rather high price charged for a basket of rolls was justified as follows: “Our rolls are hand baked for us daily using only the purest ingredients: finest organic grains, fertile eggs, organically grown onions & raisins, raw butter, oils & honey.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

January 18, 2013

Busboys

Have you ever wondered how many items in a first-class restaurant are placed on and later removed from a table of two diners? Think of tablecloths, napkins, bread plates, water and wine glasses, candles, flower vases, six or more separate pieces of silverware for each, some of them replaced during the meal, salt and pepper shakers, condiment bottles, butter and olive oil holders, bread baskets, not to mention all of the food-bearing dishes in a multi-course meal . . .

Have you ever wondered how many items in a first-class restaurant are placed on and later removed from a table of two diners? Think of tablecloths, napkins, bread plates, water and wine glasses, candles, flower vases, six or more separate pieces of silverware for each, some of them replaced during the meal, salt and pepper shakers, condiment bottles, butter and olive oil holders, bread baskets, not to mention all of the food-bearing dishes in a multi-course meal . . .

In 1929 a highly systematized hotel chain that kept track of these things – probably the Statler – declared the number was 100. Most of the items were brought and removed by the waiter’s waiter, the busboy. (There were no busgirls then, few now.)

The busboy’s job also entailed ferrying heavy loads of dishes, glasses, and silverware – clean and dirty – to and from the kitchen which was often in the basement. And, should anything be broken or spilled by anyone, it was his job to clean it up. And to keep the waiter happy. In European restaurants, and perhaps a few in America, the waiter never entered the kitchen, this being delegated to his busboy.

Omnibus boy was the name of the position in the 19th century, meaning a restaurant worker who does all kinds of menial jobs. Around the turn of the last century it was shortened to busboy, and after World War I the longer word was rarely used. The word “boy” of course is routinely applied to holders of lowly jobs, all the more so if they are black or ethnic minorities as so often happens. Historically many busboys were in fact in their 30s and 40s.

The job can work out as an apprenticeship particularly useful for those who are learning English as an additional language. Many stories tell of those who began as busboys, such as Oscar Tschirky of Switzerland, maître d’hôtel of Delmonico’s and the Waldorf, who rose to high positions in hotels and restaurants. This was unusual. Mere survival was difficult enough in a position so strenuous and poorly paid. A bus boy revealed in 1920 that he received $15 a week plus meals for working an 11-hour shift that ran from 7:30 pm until 6:30 am. Meals were no small thing to busboys, nor to other restaurant personnel. Some hotels and restaurants paid no wages to busboys, considering them in the employ of the waiters. In any case, waiters were, and are, expected to share their tips with busboys.

The classic European uniform for busboys – not often adopted in the US — consisted of a short black jacket, black tie (in contrast to the waiter’s white tie), and a long apron. Over time busboy uniforms have become varied, though usually inconspicuously so. However, in the 1980s busboys at Sonny Bono’s restaurant in Palm Springs wore T-shirts decorated with his picture.

© Jan Whitaker 2013

January 8, 2013

Greek-American restaurants

Ethnic restaurants are generally seen as places where people from cultures outside the U.S. provide meals similar to what they ate in their homelands. A high degree of continuity between restaurant owners, cooks, and cuisines is presumed, as in: the Chinese run Chinese restaurants in which Chinese cooks prepare Chinese dishes.

Questions are sometimes raised about whether, for example, Chinese restaurants in America have adapted to American consumer’s tastes to the point where the Chinese cuisine is not “authentic,” but few question how obviously true or historically accurate it is to assume that Chinese always cooked or served Chinese food.

History is rarely tidy. Chinese, Germans, and Italians cooked French food. Germans ran English chop houses. And people of almost all ethnicities — Irish, Italian, German, Croatian, Greek — cooked American food and owned American restaurants.

Greek immigrants, in fact, have been especially inclined to run American restaurants which serve mainstream American food, with little suggestion of the Mediterranean. Typically they’ve been the independent quick lunches, luncheonettes, coffee shops, and diners that are open long hours, serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner to working people. Many have been run under business names such as Ideal, Majestic, Elite, Cosmopolitan, Sanitary, Purity, or Candy Kitchen, rather than the proprietor’s name.

Greek immigrants, in fact, have been especially inclined to run American restaurants which serve mainstream American food, with little suggestion of the Mediterranean. Typically they’ve been the independent quick lunches, luncheonettes, coffee shops, and diners that are open long hours, serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner to working people. Many have been run under business names such as Ideal, Majestic, Elite, Cosmopolitan, Sanitary, Purity, or Candy Kitchen, rather than the proprietor’s name.

The emphasis on names suggesting quality or cleanliness is explained by the tendency of Americans in the early 20th century to brand Greek-run eateries as “greasy spoons” or “holes in the wall.” A negative attitude to Greek eating places is evident in the following piece of rhyme published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1926 entitled “Where Greek Meets Greek”:

The other day I wandered in where angels fear to tread –

I mean the well known Greasy Spoon, where hungry gents are fed;

Where eats is eats and spuds is spuds, and ham is ham what am –

And the pork in the chicken salad is honest-to-goodness lamb.

Certainly there were substandard Greek restaurants, but I’ve found that Greek-American proprietors had a propensity to plow profits into modern equipment and fixtures whenever possible.

Greek immigrants showed strong affinity with the restaurant business since the beginning of the 20th century when they began coming to the U.S. in large numbers. The reason for this is often attributed to a lack of English skills, but the first Greek restaurants, actually coffeehouses where patrons could linger, probably had more to do with the absence of women among early Greek migrants. Coffeehouses furnished community. Although in big Eastern cities many Greek restaurants continued to focus on Greek immigrants, many enterprising Greeks took the step of expanding beyond their compatriots. Some, such as Charles Charuhas who established the Washington, D.C. Puritan Dairy Lunch in 1906, were expanding or transitioning from the confectionery and fruit business.

While heavily invested in the New England lunch room business, especially in Providence RI and Lowell MA, Greek immigrants spread to many regions of the U.S, bringing restaurants to the restaurant-starved South. It is impressive that a Raleigh-based Greek trio opened its 15th restaurant in North Carolina as early as 1909. At that time, Greeks were said to be “invading” the lunch room trade in Chicago, operating about 400 places. Because of the simplicity of American cuisine, it was said that two months spent shadowing an American cook was all it took for Greek restaurateurs to pick up the necessary skills.

Other successful Greek restaurateurs of the past century included John Raklios who at one point owned a chain of a couple dozen lunch rooms in Chicago. In New York City Bernard G. Stavracos ran the first-class restaurant The Alps on West 58th, established in 1907. The Demos Cafe in Muskegon MI was one of that city’s leading establishments. In Dallas The Torch of the Acropolis (pictured) had a 36-year-long run, closing in 1984, while the College Candy Kitchen was an institution in Amherst MA.

Other successful Greek restaurateurs of the past century included John Raklios who at one point owned a chain of a couple dozen lunch rooms in Chicago. In New York City Bernard G. Stavracos ran the first-class restaurant The Alps on West 58th, established in 1907. The Demos Cafe in Muskegon MI was one of that city’s leading establishments. In Dallas The Torch of the Acropolis (pictured) had a 36-year-long run, closing in 1984, while the College Candy Kitchen was an institution in Amherst MA.

The children of successful Greek restaurant owners often preferred professional careers, but a new wave of Greek immigrants arrived after WWII, gravitating to diners, particularly it seems, in New Jersey. In 1989 the author of the book Greek Americans wrote that according to his estimate about 20% of the members of the National Restaurant Association had Greek surnames. And, as if demonstrating a flair for adaptation, according to a 1990 study, Greek-Americans were then dominating Connecticut’s pizza business.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

January 3, 2013

Roadside attractions: Toto’s Zeppelin

As alcoholic beverages made their return in the early 1930s, supper clubs and roadhouses offering meals, entertainment, and good cheer sprang up on highways and byways across the nation. Eager to attract customers, some adopted unusual designs that, on the surface at least, promised something out of the ordinary.

As alcoholic beverages made their return in the early 1930s, supper clubs and roadhouses offering meals, entertainment, and good cheer sprang up on highways and byways across the nation. Eager to attract customers, some adopted unusual designs that, on the surface at least, promised something out of the ordinary.

One of them was Salvatore “Toto” Lobello’s place on the main road leading from Holyoke to Northampton MA. It looked like the German Graf Zeppelin that was always in the news with tales of travelers gliding through the sky while enjoying its deluxe dining and sleeping accommodations.

One of them was Salvatore “Toto” Lobello’s place on the main road leading from Holyoke to Northampton MA. It looked like the German Graf Zeppelin that was always in the news with tales of travelers gliding through the sky while enjoying its deluxe dining and sleeping accommodations.

The fantastic building was a type of roadside architecture of the late 1920s and 1930s commonly associated with California where sandwich shops and refreshment stands resembled oversized animals and objects ranging from toads to beer kegs. The zeppelin-shaped building was constructed in 1933 by Martin Bros., a well-known Holyoke contractor experiencing serious financial distress at that time. The nightclub apparently failed to open and, in 1934, suffered fire damage (for the first, but not the last, time).

In December of 1935, after months of trying to obtain a liquor license, Toto Lobello announced the grand opening of the Zeppelin. He solved the licensing problem by teaming up with Lillian and Adelmar Grandchamp who were able to transfer the license from their recently closed downtown Holyoke restaurant, the Peacock Club.

The advertisement for the opening of “New England’s Smartest Supper Club” announced that drinks would be available in the Modernistic Cocktail Lounge, which was on the ground floor below the dirigible-shaped dance hall. With Web Maxon and his orchestra providing dance music, and a promise of “Never a Cover Charge, Always a Good Time,” the Zeppelin soon became a popular place for nightlife generally and for dinner parties of organizations such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus.

The advertisement for the opening of “New England’s Smartest Supper Club” announced that drinks would be available in the Modernistic Cocktail Lounge, which was on the ground floor below the dirigible-shaped dance hall. With Web Maxon and his orchestra providing dance music, and a promise of “Never a Cover Charge, Always a Good Time,” the Zeppelin soon became a popular place for nightlife generally and for dinner parties of organizations such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus.

Toto Lobello also had a confectionery business in Northampton located on Green Street across from the campus of the all-women Smith College. Like the confectionery, the Zeppelin became one of the students’ favorite haunts for the 3-Ds (dining, dancing, and drinking). According to an informal survey in 1937 the majority of Smith students liked to drink, preferring Scotch and soda, champagne, and beer. Toto’s ranked as a top date destination.

Toto Lobello also had a confectionery business in Northampton located on Green Street across from the campus of the all-women Smith College. Like the confectionery, the Zeppelin became one of the students’ favorite haunts for the 3-Ds (dining, dancing, and drinking). According to an informal survey in 1937 the majority of Smith students liked to drink, preferring Scotch and soda, champagne, and beer. Toto’s ranked as a top date destination.

Toto’s Zeppelin served lunch and dinner and a special Sunday dinner for $1.00. On Saturday nights Charcoal Broiled Steak was featured.

One year after Toto’s grand opening the restaurant/nightclub faced a licensing renewal challenge requiring it to withdraw its application until unspecified “improvements” were made to the facility. But a more serious problem was about to emerge when dirigibles suddenly lost their appeal following the May 1937 Hindenburg disaster in which 36 people perished. Not too much later, in November of 1938, fire would also completely destroy Holyoke’s Zeppelin. In rebuilding, Toto chose a moderne style with a pylon over the entrance.

In the mid-1950s Salvatore Lobello, owing the state a considerable sum for unpaid unemployment taxes, filed for bankruptcy. He closed his Northampton restaurant, auctioning off all the fixtures in 1957. The building, at the address now belonging to a pizza shop, was razed. The Holyoke restaurant continued in business until 1960 when it was seized by the federal government for nonpayment of taxes. It briefly did business as the Oaks Steak & Rib House, a branch of the Oaks Inn of Springfield, before its destruction by fire in 1961.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

December 27, 2012

2012, a recap

I had a pleasant surprise when I looked over my numbers for the past year and discovered that my page views had increased by 78%. As a “niche blogger” my biggest question is whether anyone is reading what I write and I am happy to report you are. Thank you!

My “Tastes of a decade” posts are so popular that I decided to make them easier to find by gathering them together on a special page. Now my mission is to fill in missing decades, starting with 1910-1920 and 1970-1980.

Just like last year, readers continue to be attracted to the well-loved restaurants of the past, the London Chop House, Schrafft’s, and Maxwell’s Plum. But even they were outdone. A new TV show set in Miami Beach in 1959 called “Magic City” propelled my 2011 post on Wolfie’s into the rank of second most visited post of 2012! Taste of a decade: 1920s restaurants, written way back in 2008, continued as no. 1.

Holding its own quite nicely is one of my favorites — “You want cheese with that?” – written over three years ago.

Holding its own quite nicely is one of my favorites — “You want cheese with that?” – written over three years ago.

Two posts I wrote in 2012 made it into this year’s Top 20. One of them surprised me: Miss Hulling’s cafeteria in St. Louis. Maybe the traffic it attracted is accounted for by someone linking to it but so far I haven’t detected any evidence of that. Ice cream parlors, published in August, was the other top new post. The popularity of this one is easy to explain: it was chosen as a featured post by WordPress.

I am constantly adding to my list of ideas for future posts, so much so that it never seems to get any shorter. Some topics in the pipeline are: Greek-American restaurants, Nick’s Nest (a hotdog stand in Holyoke MA), sawdust floors, frozen entrées, menu design, chains of theme restaurants, and lunch wagons. If I can find enough material I’d love to write about the Kahiki in Columbus OH, which was perhaps the most exuberant example of a Polynesian restaurant in this country. A reader has suggested writing about Bookbinder’s in Philadelphia. So, as usual I expect to be working on many topics simultaneously.

Best wishes to everyone for a happy new year!

December 20, 2012

Christmas dinner in a restaurant, again?

I suspect that a lot of people living in the Wild West in the 1880s and 1890s had little choice but to eat their holiday dinners in restaurants. The majority of the residents of western mining and ranching towns were males living in “hotels” which were nothing but crude rooming houses with a saloon, pool hall, and none-too-fine restaurant attached.

I suspect that a lot of people living in the Wild West in the 1880s and 1890s had little choice but to eat their holiday dinners in restaurants. The majority of the residents of western mining and ranching towns were males living in “hotels” which were nothing but crude rooming houses with a saloon, pool hall, and none-too-fine restaurant attached.

John W. Conway ran such a place in Santa Fe NM, but judging from the spread he laid out for Christmas in 1891, he was making a generous effort to please his guests with a delicious meal. On this particular day he served a genuine feast for only 25 cents, the price of an everyday dinner.

Just down San Francisco street, Will Burton offered a more refined, pared-down dinner. Judging from the menu, the 50-cent meal might well have equaled one served in more sophisticated big city restaurants. Unlike John Conway’s, his dinner began with oysters and featured fish and game courses. And there was no Pork and Beans or Cornstarch Pudding on Will’s menu.

Will, aka Billy, had lived for a time in San Francisco where he may have acquired elite tastes. He hosted game dinners, kept vintage French wines in his cellar, and poured expensive Scotch whisky. He opened this restaurant in Santa Fe on Thanksgiving of 1891 but, alas, by the next spring he was ruined and reduced to running the short order department at Conway’s Bon Ton.

Regarding the first menu, I am left wondering what Nellie Bly pudding might be. Under Relishes on the same menu, German pickles were, I think, pickled green tomatoes with onions and green peppers. Chow Chow was a mixture of pickled vegetables. On Billy’s menu, Velouté Sauce, of meat stock, and creamed flour and butter, is incorrectly spelled. “A. D. Coffee” is short for after dinner coffee. Both menus use the French meaning of entree, a side dish usually of smaller cuts or chopped meat or fowl.

I find it interesting that Christmas dinner menus in most of the restaurants I looked at from the second half of the 20th century were far less elaborate than these.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

December 13, 2012

Fortune’s cookies

They’ve been used in political campaigns, as a method of publicizing new movies, and as a clever way to announce engagements, but most people have encountered fortune cookies in Chinese restaurants.

They’ve been used in political campaigns, as a method of publicizing new movies, and as a clever way to announce engagements, but most people have encountered fortune cookies in Chinese restaurants.

Searching for their origins in old Chinese customs is pointless because the fortune cookie was almost certainly “invented” in America, in California to be more specific. And probably by Japanese confectioners as a variety of senbei wafers.

Yet, even with their probable Japanese origins, there is nothing particularly Asian about them. The idea of embedding charms or slips of paper with fortunes on them in pastries and candies is an old idea in Western culture. The Victorians loved such things. Halloween was a popular time for fortune cakes and cookies and even fortune popcorn balls. A 1903 book suggested fortunes such as “You are going to marry and live abroad.” and “Thy flour barrel shall never be empty.”

Precisely why they were adopted by Asian restaurants remains a mystery. Could it have been that restaurant proprietors knew finding fortunes was popular with their non-Asian customers? Or was it the need to supply some kind of dessert to Western customers with a sweet tooth? A 1939 menu from San Diego’s Chinese Village restaurant shows Mixed Candy and Oolong Tea as finales to $1.00 and 75-cent meals but tea and Fortune Cookies with a 50-cent dinner.

Precisely why they were adopted by Asian restaurants remains a mystery. Could it have been that restaurant proprietors knew finding fortunes was popular with their non-Asian customers? Or was it the need to supply some kind of dessert to Western customers with a sweet tooth? A 1939 menu from San Diego’s Chinese Village restaurant shows Mixed Candy and Oolong Tea as finales to $1.00 and 75-cent meals but tea and Fortune Cookies with a 50-cent dinner.

As to when fortune cookies made their debut, there is general agreement that it was in the early 20th century, before World War I. Certainly they are never mentioned in stories about Chinese restaurants in the 19th century. Many have claimed to be the cookie’s inventor, but Jennifer 8. Lee, author of The Fortune Cookie Chronicles, thinks it likely that around 1910-1914 Makoto Hagiwara introduced them as accompaniments to tea at the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco where he was the concessionaire.

The cookies came into widespread restaurant use across the United States after WWII. For some inscrutable reason they also became frequent topics of gags in comic strips, newspaper gossip columns, and comedians’ routines. The fictive message “Help, I’m a prisoner in a Chinese cookie factory,” is one that falls flat with Asian-American cookie producers. But if you ask me most of the jokes are remarkably unfunny including the one from Archie comics.

The cookies came into widespread restaurant use across the United States after WWII. For some inscrutable reason they also became frequent topics of gags in comic strips, newspaper gossip columns, and comedians’ routines. The fictive message “Help, I’m a prisoner in a Chinese cookie factory,” is one that falls flat with Asian-American cookie producers. But if you ask me most of the jokes are remarkably unfunny including the one from Archie comics.

Writing fortunes was a part-time job for somebody’s cousin or a freelance writer, Asian or not, who would come up with a fresh batch of several hundred at a time. Supposedly beginning with translations from much-abused Confucius, eventually anything – anything at all – provided inspiration. Occasionally they are offensive to patrons, as exemplified by the 1942 lulu, “Every woman like to be taken with a grain of assault.”

By the 1970s production of cookies was fully mechanized and they were turned out in huge batches by Japanese and Chinese makers who supplied restaurants all over the country. Today they are an unquestionable part of American restaurant history, one that has spread around the world.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012