Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 36

December 22, 2013

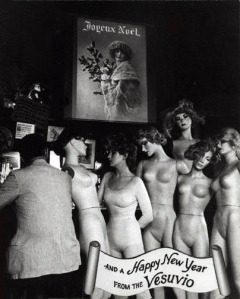

Holiday greetings from Vesuvio Café

I wish I could explain the Vesuvio’s holiday cards, but I can’t. Maybe it’s enough to know that the Café was a beatnik gathering spot in San Francisco.

The café was founded in 1949 by Henry Lenoir, who wore a beret and undoubtedly preferred to spell his first name as Henri. I’m guessing he’s the aging cherub on the left on the 1956 postcard above. I couldn’t find much about him other than that he was born in Massachusetts around 1904. The son of a Swiss university professor, he was a college graduate at a time when that was fairly unusual. In 1940, before he opened the café, he worked as a salesman in a San Francisco department store that I like to think was the Emporium. He was an art lover who enjoyed the company of beats and hipsters.

I don’t know if the Vesuvio served much food. It seemed to be more of a drinking than an eating place back in the days when Henry presided behind the bar. A sign in the window advertised “booths for psychiatrists” and a “Gay ‘90s Color Television” flashed old photos of women clad in bloomers. In the late 1950s it was on the North Beach circuit for beatniks who made the rounds from the Vesuvio to the Coexistence Bagel Shop and a nameless bar called “the place.” No doubt they stopped in at the City Lights bookstore too; Henry lived upstairs.

It was the day of the Hungry I, the Purple Onion, and the Anxious Asp (where the restroom was papered with pages from the Kinsey Report). “The place” and the Coexistence, considered the birthplaces and headquarters of the San Francisco beats, were both gone by early 1961. But, although Henry sold the Vesuvio in 1970, it continues even today. Of course it isn’t the same. Given that Beatnik dens became tourist sites almost overnight, it already wasn’t the same in 1964 when the card with the 5 nude mannequins and one real woman modestly dressed in a long-sleeve leotard was produced.

It was the day of the Hungry I, the Purple Onion, and the Anxious Asp (where the restroom was papered with pages from the Kinsey Report). “The place” and the Coexistence, considered the birthplaces and headquarters of the San Francisco beats, were both gone by early 1961. But, although Henry sold the Vesuvio in 1970, it continues even today. Of course it isn’t the same. Given that Beatnik dens became tourist sites almost overnight, it already wasn’t the same in 1964 when the card with the 5 nude mannequins and one real woman modestly dressed in a long-sleeve leotard was produced.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

December 17, 2013

The Shircliffe menu collection

Arnold Shircliffe spent his life in the catering trade, working in almost every branch of it. He held jobs in railroad dining cars, the Army, hotels, clubs, and restaurants. He began as supervisor of a dining car in 1902, remaining in that occupation for a couple of decades before becoming catering manager of the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. While there he published the Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book in 1926. Around 1936 he became manager of the restaurant in Chicago’s Wrigley Building, then known as Grayling’s, a position he held until his death in 1952.

Arnold Shircliffe spent his life in the catering trade, working in almost every branch of it. He held jobs in railroad dining cars, the Army, hotels, clubs, and restaurants. He began as supervisor of a dining car in 1902, remaining in that occupation for a couple of decades before becoming catering manager of the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. While there he published the Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book in 1926. Around 1936 he became manager of the restaurant in Chicago’s Wrigley Building, then known as Grayling’s, a position he held until his death in 1952.

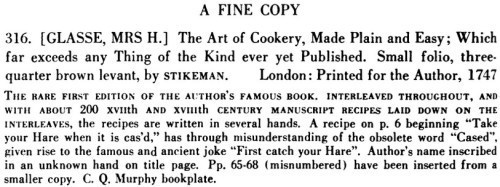

By 1928 he had amassed an impressive collection of cook books that included a first edition of Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy published in London in 1747. Somewhat later he began to collect menus.

In 1954, two years after Arnold Shircliffe’s death, his son Harold auctioned his father’s collection which by then was vast and focused mainly on antique cook books. It also included what was described in the auction catalog of the Parke-Bernet Galleries in NYC as “the Pride and Joy of His Life,” about 14,000 menus. The catalog has been digitized as part of the Hathi Trust and can be viewed in its entirety.

I have been able to find only two auction records from the sale of the 697 lots in the Shircliffe auction. Mrs. Glasse’s folio-edition book went for $300. The sum is equivalent to several thousand dollars today but it strikes me as very low. Another rarity, William Turner’s A New Boke of the Natures and Properties of All Wines That Are Commonly Used Here in England, published in 1568, brought $500.

The menus were grouped in lots numbered 354, 420-422, and 470-473. I find #354 quite fascinating. It is described as a Horn Book Menu made of wood, almost 8 inches tall and 3 inches wide, with a handle and a manuscript menu labeled “The Carte of the Palais Royal Dinner,” presumed to be English from the 19th century. In a 1943 note, Arnold wrote about a horn book he displayed at a culinary exhibit put on by the Societe Culinaire Philanthropique de New York at the Hotel Commodore. He said that horn books were originally worn around children’s waists and used for studying the ABCs, prayers, etc. Then, he wrote, “The model of the horn book or paddle was taken up by the restaurateurs and they used same as a menu – when it was issued to the waiter, his name was placed upon it; this hung from the waiter’s side in many restaurants and the menu was read to the guest. The menu or horn book was charged to the waiter, and when he left the service or was discharged, his name was scratched off and the name of the new waiter placed on same.”

The largest auction lot of menus was #470 which held an estimated 10,000 items, many from 19th-century American hotels. In it was a tavern broadside from 1790 showing the set price for “the best dinner,” but the oldest true bill of fare, from The Rainbow in NYC, was dated 1838.

The largest auction lot of menus was #470 which held an estimated 10,000 items, many from 19th-century American hotels. In it was a tavern broadside from 1790 showing the set price for “the best dinner,” but the oldest true bill of fare, from The Rainbow in NYC, was dated 1838.

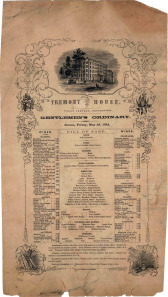

In another annotation for the exhibition of the Societe Culinaire Philanthropique Arnold explained that the Tremont House in Boston was one of the first to issue written menus. He added, “The earliest hotel menu that I have is dated 1825.” No menu from a date this early appeared in the list of highlighted items in lot #470, however there was a menu from the Tremont House dated August 25, 1844, that was similar to that of May 1844 shown above.

In 1955 Arnold’s son donated 10,000 menus to the New York Historical Society. A short time later the Historical Society put them on display with the bill of fare from The Rainbow included. This leads me to believe that it was lot #470 that Harold Shircliffe donated. The Historical Society’s notes on the Shircliffe Menu Collection say only that “The core of the collection was assembled by Arnold Shircliffe but has been added to since its donation.” I can’t help but wonder if lot #470 had failed to receive any acceptable bids — or any bids at all – and that was the reason for the donation.

The NYHS menu collection is viewable at the Historical Society’s Patricia D. Klingenstein Library on a walk-in basis (registration with a photo ID required). An electronic database of what is contained in the collection is available at the library.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

December 8, 2013

Books, etc., for restaurant history enthusiasts

TURNING THE TABLES: RESTAURANTS AND THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920, by Andrew P. Haley, University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

In the time that has elapsed since my reading this fine book — and getting to meet Andrew in person — and now, he has gathered numerous glowing reviews plus a 2012 James Beard Award. Proving he didn’t need any help from me to get the attention he deserved for this well-researched and highly readable book. Still, I’d like to see him get even more.

In the time that has elapsed since my reading this fine book — and getting to meet Andrew in person — and now, he has gathered numerous glowing reviews plus a 2012 James Beard Award. Proving he didn’t need any help from me to get the attention he deserved for this well-researched and highly readable book. Still, I’d like to see him get even more.

Turning the Tables is an investigation of the role of the American middle class in the creation of restaurants that suited their tastes, values, and habits: in other words, in creating the kinds of restaurants we patronize today, where the menu is streamlined and written in plain English, where women and children are welcome, and where food of many ethnicities is enjoyed. The book investigates in detail what it was about elite restaurants of the late Victorian age that average Americans disliked. And I must say it is refreshing to read an account of the making of our culture that portrays average people “turning the tables” and spreading access to the good things of life rather than aspiring to become privileged exclusivists.

HISTORIC RESTAURANTS OF WASHINGTON D.C., by John DeFerrari, The History Press/American Palate, 2013.

John is a preservationist and an authority on Washington. He is the author of Lost Washington and of the well-illustrated blog Streets of Washington. His book on the city’s restaurants is carefully researched and beautifully illustrated with postcards from his collection and photographs from the Library of Congress. There are eight pages of color illustrations, the remainder in black and white. Reading the book makes clear that even if Washington’s restaurants – like those of many cities across the nation – were long considered of little culinary interest, that doesn’t mean that their histories are any less significant. John has ferreted out plenty of evidence of the important role they played in the life of the city.

John is a preservationist and an authority on Washington. He is the author of Lost Washington and of the well-illustrated blog Streets of Washington. His book on the city’s restaurants is carefully researched and beautifully illustrated with postcards from his collection and photographs from the Library of Congress. There are eight pages of color illustrations, the remainder in black and white. Reading the book makes clear that even if Washington’s restaurants – like those of many cities across the nation – were long considered of little culinary interest, that doesn’t mean that their histories are any less significant. John has ferreted out plenty of evidence of the important role they played in the life of the city.

I particularly liked his chapters “Black Washington’s Restaurants” and “Power Lunches and Dinners.” And, of course, I appreciated that he included a chapter on tea rooms. I know I will be dipping back into his book many times as I write my own posts.

REPAST: DINING OUT AT THE DAWN OF A NEW AMERICAN CENTURY, 1900-1910, by Michael Lesy and Lisa Stoffer, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013

Michael Lesy is of course the author of the newly reissued, haunting classic Wisconsin Death Trip, as well as numerous other books. In Repast he has teamed up with his wife Lisa Stoller to write about turn-of-the-century dining, high and low, American, French, and other ethnicities. Splitting the task between them almost 50-50, Michael authored the Introduction and the chapters Pure Food, Quick Food, and Other People’s Food while Lisa wrote Her Food, Splendid Food, and the Afterword. Together the chapters create a vivid portrait of how people lived as reflected through their eating habits.

Michael Lesy is of course the author of the newly reissued, haunting classic Wisconsin Death Trip, as well as numerous other books. In Repast he has teamed up with his wife Lisa Stoller to write about turn-of-the-century dining, high and low, American, French, and other ethnicities. Splitting the task between them almost 50-50, Michael authored the Introduction and the chapters Pure Food, Quick Food, and Other People’s Food while Lisa wrote Her Food, Splendid Food, and the Afterword. Together the chapters create a vivid portrait of how people lived as reflected through their eating habits.

The book makes great use of the New York Public Library’s Buttolph menu collection which is particularly strong in the first decade of the 20th century. Many of the photographs shown in the book are from the incomparable Byron Company collection at the Museum of the City of New York. As a consequence, the book tends to favor New York particularly in the illustrations, which are printed beautifully in this handsome, full-color book.

The sprightly image of a menu from McDonnell’s Drive-In shown here, in 1940s Los Angeles, is from CC’s mixed set of ten cards, the American Collection. Other note card sets in their lineup include those of the Old West and the cities of Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. I like how the inside left side of each card gives a glimpse of the menu’s interior.

The sprightly image of a menu from McDonnell’s Drive-In shown here, in 1940s Los Angeles, is from CC’s mixed set of ten cards, the American Collection. Other note card sets in their lineup include those of the Old West and the cities of Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. I like how the inside left side of each card gives a glimpse of the menu’s interior.

And, in case you were wondering what that brown bottle is that the female carhop carries on the tray, it is indeed beer. In addition to colas, ice cream sodas, and “churned buttermilk,” McDonnell’s served bottled beer and beer by the glass (10 cents), with a higher charge for Eastern beers than those brewed in the West! So let’s drink a toast to California’s unique concept of the drive-in and to Cool Culinaria’s mission of “Rescuing Vintage Menu Art from Obscurity.”

December 1, 2013

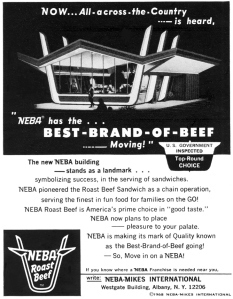

Roast beef frenzy

According to Mike Davis, creator of the Neba chain, the arrival of fast-food roast beef sandwiches in the early 1960s was a sign of an upward-bound middle class able to afford its beef sliced rather than ground to bits. His sandwiches cost 69 cents as against the 15 or 20 cents for a chain burger.

Indeed, sliced beef was big. Despite being first into the beef sandwich market, by 1967 Neba faced competition from Arby’s, Beef Corral, RoBee’s (soon to become Roy Rogers), Heap Big Beef (with its odd Indian theme), and others. Burger King and McDonald’s were testing roast beef in some of their units and Minnie Pearl’s was poised to add roast beef to its chicken menu.

Davis began his fast food career with submarine sandwiches, branching into roast beef in 1960 because it was easier to produce in quantity and not commonly found in chain restaurants. There are various ideas about where the name Neba came from. Almost certainly it was not an abbreviation for “Never eat burgers again.” As strange as it sounds, it’s likely that Neba was chosen because it was the name of a dog once owned by Davis, as he said in a 1969 interview. “Nicest eating beef around,” sometimes used as an advertising slogan, may have been a back formation.

Davis began his fast food career with submarine sandwiches, branching into roast beef in 1960 because it was easier to produce in quantity and not commonly found in chain restaurants. There are various ideas about where the name Neba came from. Almost certainly it was not an abbreviation for “Never eat burgers again.” As strange as it sounds, it’s likely that Neba was chosen because it was the name of a dog once owned by Davis, as he said in a 1969 interview. “Nicest eating beef around,” sometimes used as an advertising slogan, may have been a back formation.

The first sandwich shops in the Neba chain were in the Albany NY area, the company’s headquarters before moving to Hollywood FL. In 1965 a Mike’s Submarine and Neba Roast Beef unit opened in Pittsfield, the first in Davis’s home state of Massachusetts. Franchised units eventually opened in Florida and southern states but the chain never made it to the West.

Davis described himself as driven to make money ever since his miserable childhood in which he earned up to $100 a week by organizing a crew of boys to deliver newspapers. Reportedly he used the money to pay rent and buy food for his brothers and sisters in an attempt to make up for parental neglect. Dropping out of school after 8th grade, he was apprehended for breaking into houses and stealing money in his teens and spent time in a reformatory. Described as “tight-lipped” and “compulsive,” he confessed he felt inhuman and never laughed.

Davis described himself as driven to make money ever since his miserable childhood in which he earned up to $100 a week by organizing a crew of boys to deliver newspapers. Reportedly he used the money to pay rent and buy food for his brothers and sisters in an attempt to make up for parental neglect. Dropping out of school after 8th grade, he was apprehended for breaking into houses and stealing money in his teens and spent time in a reformatory. Described as “tight-lipped” and “compulsive,” he confessed he felt inhuman and never laughed.

The Neba chain reached its peak in 1969 when there were 70 units in the U.S. Having sold the Canadian branch, Davis, 35, was said to be worth $15 or 20 million at that time. In 1970 he resigned as chairman a month before the corporation declared bankruptcy. With 400 units by then, Arby’s had become the competition-busting roast beef leader.

As late as the mid-1980s a few of the original Neba sandwich shops, in upstate New York and Miami FL, remained in business under new owners.

I don’t know what happened to Davis after he left the company. I’d like to think he found some degree of happiness.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

November 24, 2013

B.McD. (Before McDonald’s)

In most towns and cities across the USA the landscape is filled with fast food eateries that belong to chains, McDonald’s obviously being only one. Chain restaurants make up close to half of all restaurants today, and many of them can be classed as fast food places. A large proportion of the meals people eat away from home come from this type of eating place.

Where did people grab a quick bite before the fast food chains came along? What was the ordinary, inexpensive eating place like for so much of the last century, B.McD.?

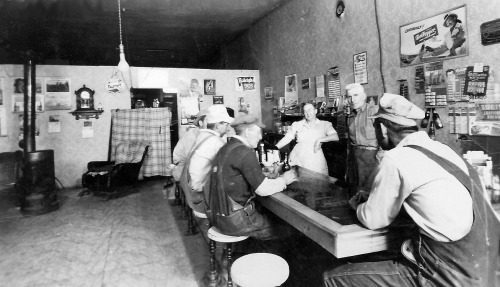

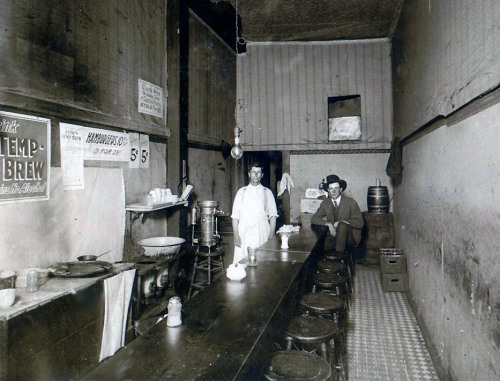

Let’s peer back into the first half of the 20th century. There were some “quick lunch” chains in existence, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Although high-traffic locations in larger cities were quickly grabbed up by chains such as Baltimore Lunch or John R. Thompson, less desirable sites in cities and on Main Streets in smaller towns were populated with small independent eateries.

Many, perhaps most, lunch rooms and cafes – not likely to be called restaurants then – occupied storefronts or freestanding one-story buildings of very basic construction. Often they were “mom & pop” operations with one of the pair handling the cooking, the other running the food service side of things. Very likely the proprietors knew most of their customers on at least a first name basis.

Most lunch rooms shared a basic floor plan in a standard storefront space 18 to 25 feet wide and 75 to 100 feet deep. About 2/3 to 3/4 of the space was devoted to the dining room, the rest making up the kitchen which was hidden behind a wall, partition, or just a curtain.

Usually seating would include both a counter and some tables or booths along the side or arranged toward the back. Very narrow storefronts had counter seating only. Shelves behind the counter or glass display cases might hold baked goods, packaged groceries, cigars, or candy. A cash register was often a prominent feature.

In many cases during Prohibition, a café’s or lunch room’s previous status as a barroom was plainly evident.

Decor, such as it was, was frequently provided by posters and stand-up signs advertising national brands, particularly soft drinks.

What was gained and what was lost when the old lunch rooms disappeared? It’s a mixed picture. I doubt that their food was much to brag about. Some were clean, some were dirty. Often their menus were limited — but rarely as limited as the fast food chains. Food was served on dishes, not in paper wrappings. They provided service and often friendliness and a sense of community, though it was sometimes circumscribed by race, gender, and familiarity.

I recall walking into a local café in Hannibal MO about ten years ago. The few customers at the counter all turned to stare openly as we came though the door. The proprietor screeched, “Where are YOU from?” We were horrified when the chili came with a big scoop of sour cream on top. She seemed offended when we failed to order pie. I hate to admit it but, all in all, I would have preferred the anonymity of a chain for lunch that day. On the other hand, if we had gone to a chain I wouldn’t remember being in Hannibal at all.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

November 17, 2013

Road trip restaurant-ing

For New Yorkers even today a lengthy car trip can raise concerns about letdowns at the dinner table, but all the more so in 1915.

For New Yorkers even today a lengthy car trip can raise concerns about letdowns at the dinner table, but all the more so in 1915.

That was the year that two writers, Theodore Dreiser and Emily Post, separately set out across country [Post pictured above, about ready to embark]. Although novelist Theodore Dreiser is often credited with writing the “first road trip” book, the publication of his Hoosier Holiday in 1916 was in fact matched by Post’s By Motor to the Golden Gate that same year.

Dreiser’s trip took him back to his boyhood state of Indiana, while Post daringly continued westward to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Diego and San Francisco. Both were in their 40s, lived in New York, and had failed marriages behind them. Both traveled with a companion and a chauffeur, in Post’s case her son.

Each made interesting observations about places where they ate. Dreiser, on a sentimental journey into his past, tended to see most restaurants as symptomatic of the identity-less mediocrity of American culture. Post experienced the journey with a liberating sense of adventure and was less judgmental than Dreiser, but only to a point.

As much as possible the Post party stuck to respectable hotels for their meals, for which they spent a fair amount of money for that time. An appendix in Post’s book provides a rundown of expenses. The joint dinner check for all three travelers usually came to between $4 and $5 plus a 10% tip even though Post reports they were light eaters.

Though she encountered some very bad meals in dingy lunch rooms, including a barroom in New Mexico where no plates were provided, Post was most critical of the dining room of Chicago’s much-ballyhooed Blackstone Hotel. She compared it unfavorably to Cleveland’s Statler Hotel [pictured] where she found the food and service “extraordinary.” Dreiser saved his greatest praise for a quick lunch eatery in Princeton IN and another restaurant in Vermilion OH where he enjoyed cherry pie provided by a Japanese-born proprietor (misidentified in his book, but almost certainly named Mamoru Okagi). He aimed his criticism at more pretentious places.

It’s safe to say that Dreiser, from a much humbler background than Post, disliked the hotel dining rooms of the sort Post preferred. He ridiculed their fake European elegance which aped the “Palace of Vairsigh,” as he mockingly put it.

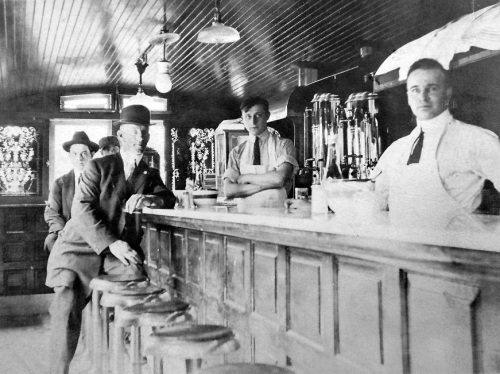

Despite, or because of, her higher social standing, Post had to juggle gender issues. She avoided hotels of the “saloon-front-and-ladies’-entrance-in-the-back variety.” Whereas Dreiser sneered at then-trendy grills and rathskellers [grill in Scranton PA pictured], Post could not even get into them. Dreiser found these types, which were so popular with men, dull and silly – “made to look exactly like a western architect’s dream of a Burgundian baronial hall”. But Post was disappointed when she was turned away from the men-only grill room of the Fontenelle Hotel in Omaha.

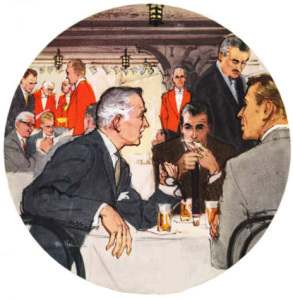

Dreiser’s discomfort was induced by stuffy dining rooms where haughty head waiters fauned over rich men — and by country lunch rooms where local “wits” hung out. The following photograph illustrates what I imagine he saw walking into some of the places he encountered on his trip.

Both cast a cold eye on the attire of other guests in upscale dining rooms. Post shuddered at the casual, wrinkled outfits worn by the wealthy, as well as at how freely California women combined colors such as “an emerald-colored fan with a sage-green frock!” But, although Dreiser was horrified by “the upstanding middle class American with his vivid suit, yellow shoes, flaring tie and conspicuous money roll,” the socialist-leaning author nevertheless said he wanted to “compose an ode” to this sort of common man of democratic society.

Summing up her travel experiences, Post reflected, “It is your troubles on the road, your bad meals in queer places, . . . , in short, your misadventures that afterwards become your most treasured memories.” Dreiser wondered, “how long will it be before we will have just a few good [restaurants] in our cities?”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

November 5, 2013

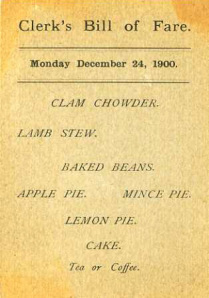

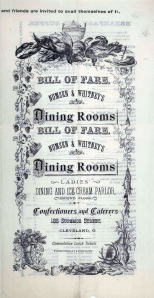

Menu vs. bill of fare

The short version is that Bill of Fare is English and Menu is French, and up until the 1920s the use of Bill of Fare was standard, but by the 1930s it had been almost universally supplanted by Menu. In a way it seems surprising that Menu won out and I wonder, was it because it’s shorter?

The short version is that Bill of Fare is English and Menu is French, and up until the 1920s the use of Bill of Fare was standard, but by the 1930s it had been almost universally supplanted by Menu. In a way it seems surprising that Menu won out and I wonder, was it because it’s shorter?

Commercially printed Bills of Fare were unknown before the late 1830s. But did that mean that previously diners had no idea what was being served until they sat down and saw what was being set out on the table? No.

As early as the American revolution, and no doubt much before that, public eating places (whether taverns, inns, coffee houses, or eating houses) provided a written list of what they were serving that day. For instance a New York paper advertised in 1777 that at Mrs. Treville’s “the bill of fare is to be seen in the coffee room every forenoon.” In other places, too, around 10 or 11 a.m. a list of what was to be served that day would appear.

How the Bill of Fare was presented is never described, alas. Since paper was rare and expensive then, I would guess that it was usually chalked on a board.

It is also interesting that more than a few eating places in the early Republic followed the (supposedly French) innovation of letting guests choose their dishes and pay accordingly rather than charging them a set fee for pre-chosen dishes. Baltimore’s Freemason’s Tavern and Coffee House in 1796 advertised that “A bill of fare, with the price of each article, will be fixed up in the public room, so that gentlemen may chuse [sic] their own dinners, at any price, from a quarter of a dollar upwards.”

In the cheapest eating places the day’s offerings were recited verbally at the door, presumably because most patrons could not read.

In the 1860s the word Menu came into use – often referred to in italics to indicate a foreign word. Special dinners and banquets at first-class eating places, such as Delmonico’s and a few hotels in the Northeast, were accompanied by souvenir Menu cards giving the dishes chosen for that event. Such a Menu, sometimes called a Carte du Diner, was often decorated with gold lettering, ribbons, and hand-colored illustrations.

By the late 1800s it was commonplace for the better hotels and restaurants to print a Menu, not Bill of Fare, for their special dinners, including those for holidays. Often some or all of the dishes were listed in French but this was not essential. As a manual published in 1896 called The Practical Hotel Steward explained, in American usage the word menu was popularly understood to indicate a “limited, choicely selected meal, as for a table d’hote dinner, a banquet, etc.”

Bill of Fare remained in use up until roughly World War I, especially among everyday lunchrooms, such as Clerk’s (shown). It was so common, in fact, that it came as a surprise to me to discover an ordinary eating place that had no association with anything French using the term Menu in the first decade of the 20th century. What led Mann Fang Lowe on Pell Street, or Van Liew’s quick lunch, both in NYC, to head their list of dishes with the word Menu?

At that time Menu still carried an association with French terms and dishes – and with a degree of snobbishness that brought forth “just folks” humor such as the following from 1914:

But change continued nonetheless. In the 1920s, many restaurants switched from Bill of Fare to Menu, yet it was still enough of a transition period to produce some strange combinations such as an American, Italian & Chinese restaurant in St. Louis that termed its list an A La Carte Bill of Fare, or the Berkeley CA restaurant that printed Menu on the outside but Bill of Fare on the inside.

By the 1930s Menu had become the norm, with no suggestion whatsoever of any French connection, so much so that it didn’t seem a bit strange that drug store lunch counters used that term. If a restaurant wanted to put on French airs they would have to resort to Carte du Jour.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

October 31, 2013

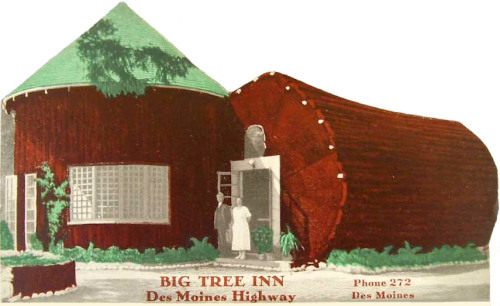

Odd restaurant buildings: Big Tree Inn

Was there ever a building or structure so strange, so awkward, so ugly that no one yearned to turn it into a restaurant?

Chicken coop, stable, giant tree stump. Why not? Especially if it was likely to catch the eye of speeding motorists and get them to stop out of sheer curiosity if nothing else.

That’s not to say that the Big Tree Inn, for instance, had nothing to recommend it but its oddness, but it certainly had plenty of that. Built from two sections of a redwood log it was designed to exhibit Humboldt County CA’s wood products at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

That’s not to say that the Big Tree Inn, for instance, had nothing to recommend it but its oddness, but it certainly had plenty of that. Built from two sections of a redwood log it was designed to exhibit Humboldt County CA’s wood products at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

The stump house, 20 ft in diameter, plus its associated log structure, was contrived by the Rodney Burns Redwood Novelty Co. and shipped by rail in sections to San Francisco where it was reassembled.

Following the exposition, a realtor in Washington state bought the log structure, transporting it to Des Moines WA at great cost. Then he added a kitchen and dining room. The odd building quickly proved a great attraction to gawkers.

The realtor’s intentions in buying the two-part building are unclear – if he had hoped to make money from the redwood structure he was evidently disappointed. For several years the property languished among the real estate listings even though it was described as “very desirable for a chicken dinner place.”

Finally, in 1923 a couple from Seattle, middle-aged and recently married Andrew and Katherine Swanson, bought the Big Tree Inn. Andrew was a bookbinder, an occupation with no seeming suitability for operating a restaurant. Katherine, however, had worked as a cook.

The two managed to make a success of the venture, running it as a seasonal business for 20 years. A 1930 postcard shows Katherine standing in front of the Big Tree with her new Oldsmobile.

It was a popular destination for parties of city dwellers wanting chicken or steak dinners – or other dishes listed on the menu shown above such as Minced Ham and Pickle Sandwiches. In 1925 a Seattle newspaper advertised the Big Tree as “The Most Unique and Attractive Summer Resort in Washington” – On Des Moines Highway – Family Chicken Dinner, $2.00 – Special ½ Fried Chicken, on Toast, 50c. Not necessary to phone. We are always ready to serve.”

The Big Tree Inn’s location on a heavily traveled highway between Seattle and Tacoma was essential to its success, so when the highway was rerouted in 1938 the Big Tree Inn followed. The Swansons sold it in 1944. The building survived a bad fire in 1946 and was back on the market five years later, described as a “summer gold mine on main hiway” that was “ideal [for] couple management.” What happened to it after that I don’t know.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

October 24, 2013

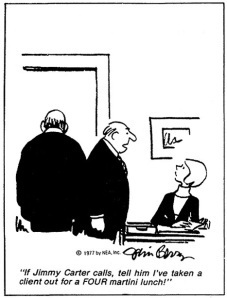

The three-martini lunch

Living as we do in the era of lunch at your desk, the three-martini lunch might well conjure up appealing images of editors and advertising executives on expense accounts, clinking glasses over a leisurely repast at New York’s “21″ Club as they sign up famous authors or land new clients.

Living as we do in the era of lunch at your desk, the three-martini lunch might well conjure up appealing images of editors and advertising executives on expense accounts, clinking glasses over a leisurely repast at New York’s “21″ Club as they sign up famous authors or land new clients.

But just how common was the three-martini lunch?

Martini cocktails became popular in the 1890s and no doubt were often enjoyed at noontime, but the phrase “three- (or two- or four-) martini lunch” did not come into use before the 1950s.

It was more a political slogan than a description of what was swallowed at lunchtime.

It first cropped up in an efficiency campaign during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower when Washington bureaucrats were informed in 1953 that the long lunch, with its “two” martinis, would no longer be tolerated.

But that was a mild martini attack compared to the one Jimmy Carter would launch during his administration. In a September 1976 debate with President Gerald Ford, candidate Carter tied the “$50 martini lunch” to Republican tax laws that subsidized the pleasures of the privileged few with the taxes of hard-working folk. After he was elected, cutting business lunch income tax deductions by 50% became a contentious element in Carter’s tax reform package.

But that was a mild martini attack compared to the one Jimmy Carter would launch during his administration. In a September 1976 debate with President Gerald Ford, candidate Carter tied the “$50 martini lunch” to Republican tax laws that subsidized the pleasures of the privileged few with the taxes of hard-working folk. After he was elected, cutting business lunch income tax deductions by 50% became a contentious element in Carter’s tax reform package.

To counter Carter’s attempt at clipping expense account meal deductions, restaurant and hotel associations published surveys about what real businessmen (yes, men) did at lunch, which included the following:

• The average businessman spent $3.93 for an expense account lunch.

• Even at the “21″ Club, most lunches cost $18 to $20, not $50.

• The typical expense account lunch consisted of sandwich, french fries, vegetable, and salad.

• Coffee was the beverage most often ordered with expense-account lunches (27%), while cocktails were ordered only 3% of the time. The order of drink popularity was: coffee, soft drinks, hot or iced tea, milk, fruit or vegetable juice, shakes, cocktail, beer, wine.

In the 1970s new profiles of the drinking habits of top executives emerged. Rather than iron men who could down three martinis or other potent drinks while doing business and go back to work refreshed, they were depicted as pathetic alcoholics who had to be helped bodily out of restaurants and who collapsed onto their office couches to sleep off the effects.

In the 1970s new profiles of the drinking habits of top executives emerged. Rather than iron men who could down three martinis or other potent drinks while doing business and go back to work refreshed, they were depicted as pathetic alcoholics who had to be helped bodily out of restaurants and who collapsed onto their office couches to sleep off the effects.

But change was occurring. Martinis were out. It was becoming fashionable to sip white wine at lunch, or to spend the time at a health club. Although Carter’s tax reforms failed, in the 1980s and 1990s business lunch deductions were whittled down, first to 80%, then to 50%. The restaurant industry, contrary to predictions, was not grievously injured and lived to see another day. And many corporations instituted programs for alcoholic employees.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

October 16, 2013

Restaurant-ing in Metropolis

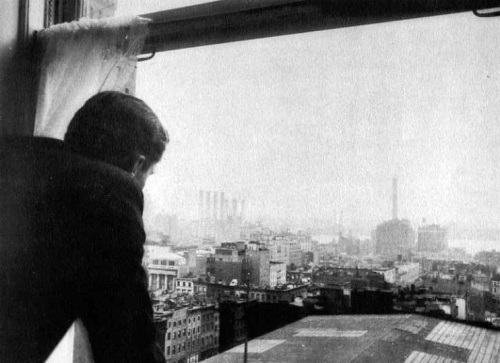

In the depths of the Depression, in 1934, Harper & Bros. published a book of 304 photographs called Metropolis. Most of the photos were by Edward M. Weyer, Jr., an anthropologist who wanted to show how people in greater NYC lived. Captions were supplied by the popular writer Frederick Lewis Allen.

In a 2010 NY Times story the book was described as a “romantic masterpiece of street photography” composed of “moody black-and-white coverage of day-to-day life in New York in the ’30s. Beggars, snow-shoveling squads, schooner crews, railroad commuters, subway crowds, tenement life, tugboats, a sidewalk craps game. . .”

I find it particularly interesting that a major focus of the book was to contrast how different social classes lived, illustrated in part by where they ate lunch.

The central narrative follows employees of a company headed by a Mr. Roberts. He lives in a house on a 4-acre plot in Connecticut, commutes to New York, and employs a house maid whose duties include fixing his wife’s lunch each day. On the day he is being profiled Mr. Roberts eats a $1.00 table d’hôte lunch at his club (equal to $17 today). So frugal, Mr. R.

Mr. Roberts is visited by a Mr. Smith from out of town (shown above looking out hotel window). Mr. Smith “stands for all those who come to the city from a distance,” whether Los Angeles, Boston, or elsewhere. He is “reasonably well off.” Mr. Smith eats a $1.25 table d’hôte lunch – er, luncheon — in a dining room on a hotel roof (pictured). Prices are high there, making his meal a relative bargain. Had he wanted to splurge he could have ordered a Cocktail (.40), Lobster Thermidor ($1.25), and Cucumber Salad (.45) – total $2.10. I would guess that many visitors to New York tend to spend more on restaurants than natives.

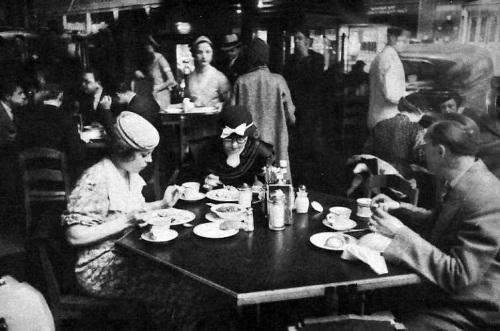

Mr. Roberts’ secretary, Miss Jordan, lives with her mother and brother in an apartment just off Riverside Drive. With a combined family income of less than $4,000 the three can barely afford their $125/month rent. She goes to lunch at a café (pictured) and orders To-Day’s Luncheon Special which consists of Tomato Juice, Corned Beef Hash with Poached Egg, Ice Cream, and Coffee, all for 40 cents. Frankly, I don’t see how she can afford to do this every day.

Miss O’Hara and Miss Kalisch transcribe dictation from other executives in the firm and each makes about $22.50 a week. Miss Kalisch lives in Astoria, Queens, and is married. Evidently she is pretending to be single in order to hold her job (her name is really Mrs. Rosenbloom). Miss O’Hara lives with her father in a somewhat decrepit apartment costing almost half her wages. He has been out of work for three years. The two women eat lunch at a drugstore counter (pictured) where they order Ham on Rye Sandwiches, Chocolate Cake, and Coffee (.30). I fear Miss O’Hara is living beyond her means if she does this often.

Miss Heilman, a young clerk, makes about $16.50 a week and is subject to occasional layoffs. She lives with her brother, his wife, and their two children in a 3-room apartment in Hoboken NJ, for which they pay $15/month. Like the other “girls” at the bottom of the totem pole she brings a sandwich and eats it in the office.

Mr. Smith, being on his own, must go out for dinner. Once again he chooses a hotel roof garden (pictured), where about half the guests are also out-of-towners. With a live orchestra and dancing, it is undoubtedly expensive. I’m guessing he went for the Cocktail and Lobster Thermidor this time.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013