Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 39

May 9, 2013

Behind the kitchen door

Although restaurant patrons often question servers about the sources of the food on the menu – whether it’s organic, local, or fresh – they rarely think about the work life of their server or other restaurant personnel. In the words of Saru Jayaraman, author of Behind the Kitchen Door, most “are totally unaware of the horribly exploitative working conditions in restaurants, which affect the quality of our food and, ultimately, our health.”

Although restaurant patrons often question servers about the sources of the food on the menu – whether it’s organic, local, or fresh – they rarely think about the work life of their server or other restaurant personnel. In the words of Saru Jayaraman, author of Behind the Kitchen Door, most “are totally unaware of the horribly exploitative working conditions in restaurants, which affect the quality of our food and, ultimately, our health.”

They do not know, for instance, that many restaurant workers earn less than poverty-level incomes in jobs that are ranked among the nation’s worst paying, are often cheated out of their earnings, and often feel compelled to work when sick. Or that female restaurant workers and all workers of color face discrimination pushing them into the lowest ranks of restaurant jobs where their chances of rising are often blocked.

Jayaraman, one of the founders of the Restaurant Opportunities Center (ROC) in 2002, wrote Behind the Kitchen Door to make the restaurant public as thoughtful about restaurant employees as they are about restaurant food, and to engage them in the movement to better workers’ pay and opportunities. The book intersperses facts about restaurant working conditions with moving stories of individuals.

If you read this book it’s true that you will probably not be quite as carefree about future restaurant experiences as you were before. You may become more selective about which restaurants you patronize. On the bright side, you may decide to help change things.

Consider the following, much of which is from surveys conducted by ROC:

● Restaurant workers made, on average, an annual income of $15,092 in 2009, one third of what other workers in the private sector made on average.

● The $2.13 federal minimum wage for tipped workers, originally calculated as one half the minimum wage (when it was $4.25), has not risen since 1991. (Restaurants are allowed to apply tips to workers’ hourly wages to meet the current $7.25 federal minimum wage.)

● The National Restaurant Association, “dominated by large multinational restaurant corporations that have a lot of money to spend on lobbyists,” such as the Darden group (Red Lobster, Olive Garden, and others) firmly opposes increases in the minimum tipped wage of $2.13.

● The National Restaurant Association, “dominated by large multinational restaurant corporations that have a lot of money to spend on lobbyists,” such as the Darden group (Red Lobster, Olive Garden, and others) firmly opposes increases in the minimum tipped wage of $2.13.

● States can set a minimum wage for tipped workers, and seven (Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) have the same minimum wage for tipped as for non-tipped workers. The NRA claims raising the minimum wage for tipped workers would create a hardship, yet the seven states “all have thriving restaurant industries,” according to Jayaraman. Look at the Department of Labor’s 2013 table “Minimum wages for tipped workers” to see how states compare.

● ROC surveys of more than 4,000 restaurant workers found that 90% had no paid sick days and most could not afford to take off work when sick. According to Jayaraman, the National Restaurant Association “has spent years lobbying to prevent restaurant workers from winning paid sick days. In Washington, D.C., the NRA struck a closed-door deal with the city council to exempt all tipped workers from a local paid sick-leave law.”

● In ROC’s national survey, “three-quarters of all white workers held a position in the front of a restaurant, while less than half of all African American and about one-third of all Latino workers held a front of the house position.” When African Americans and Latinos do work in the dining room they are most likely to be bussers – and to find it hard to get promoted to server with the chance to multiply their earnings times five or more.

These are but a few of the revelations in Behind the Kitchen Door. If the book has a single message about what to do, it is, “Adopt a definition of ‘sustainable food’ that includes sustainable labor practices.”

ROC puts out an annual National Diners Guide. Although it contains relatively few restaurants, it is worth looking at.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

April 30, 2013

Before Horn & Hardart: European automats

Note: In preparing for an interview for a documentary on Automats I looked at new sources I wasn’t aware of when I originally wrote this post in 2010, among them a wonderful German trade publication which pictures European Automats produced by the Sielaff company of Berlin. The booklet, from the Hagley Museum and Library’s digital archives, also contains rare exterior and interior shots of NYC’s first Automat, opened in 1902 by James Harcombe. I’ve made modifications to the post and have included some new illustrations.

When automats opened in New York and Philadelphia in 1902 many people were convinced they were an American invention. But they were not. A reporter for the New York Tribune captured a conversation between an American businessman and a foreign guest at James Harcombe’s NYC Automat in 1903, shortly after its opening. After examining the place, the American exclaimed, “What a tribute to American inventive skill!” The man at the next table replied, speaking with an accent, “This is a German idea. There are dozens of these restaurants on the Continent and this one was moved bodily from Berlin …” As the editors of the American Architect and Building News had observed in 1892, when it came to “penny-in-the-slot” machines the U.S. was “far behind the rest of the civilized world.” Even though Americans detested tipping, admired gadgetry, and loved fast service, for some reason the US lagged in the area of automated restaurants.

Slot machines actually go back to antiquity. The first may have been a holy water dispenser in Egypt over 2,000 years ago. But it was Germany that developed the first automatic restaurant, applying electricity to the idea of self-service. Germany was also responsible for the term “automat” which in German usage applies to any type of coin-operated dispensing apparatus. The world’s first automatic refreshment dispenser appeared on the grounds of the zoo in Berlin in June of 1895 and was considered a “howling success.” On its first Sunday in operation it sold 5,400 sandwiches, 9,000 glasses of wine and cordials, and 22,000 cups of coffee. The first “automatisches restaurant,” providing hot meals as well as sandwiches and drinks was also designed by Max Sielaff of Berlin. It was presented to the public at a Berlin industrial exposition in 1896.

Slot machines actually go back to antiquity. The first may have been a holy water dispenser in Egypt over 2,000 years ago. But it was Germany that developed the first automatic restaurant, applying electricity to the idea of self-service. Germany was also responsible for the term “automat” which in German usage applies to any type of coin-operated dispensing apparatus. The world’s first automatic refreshment dispenser appeared on the grounds of the zoo in Berlin in June of 1895 and was considered a “howling success.” On its first Sunday in operation it sold 5,400 sandwiches, 9,000 glasses of wine and cordials, and 22,000 cups of coffee. The first “automatisches restaurant,” providing hot meals as well as sandwiches and drinks was also designed by Max Sielaff of Berlin. It was presented to the public at a Berlin industrial exposition in 1896.

The fame of automatic restaurants spread rapidly in 1897 when one was installed and won a gold medal at the Brussels world’s fair. That same year an announcement was made that a similar restaurant would open soon in Philadelphia and in St. Louis – as far as I can determine neither of these became a reality at that time. In 1900 Paris had ‘buffets automatique’ — which resembled automats — all along the boulevards. Automats appeared in London a bit later. Around this time a visitor to St. Petersburg, Russia, found an automatic restaurant by the name of Quisisana, which evidently was the name of a Sielaff competitor in the European automatic restaurant industry. (pictured: top, Karlsruhe, 1903; middle, Dortmund, 1902; bottom, Wurzburg).

© Jan Whitaker, 2010, revised 2013

April 23, 2013

“Distinguished dining” awards

After World War II American consumers were filled with pent-up demand accrued over years of rationing and deprivation. They wanted to sample the joys of the good life, which included American and world travel, even if only in their imaginations. A sophisticated magazine – Holiday — was created to cater to their aspirations.

After World War II American consumers were filled with pent-up demand accrued over years of rationing and deprivation. They wanted to sample the joys of the good life, which included American and world travel, even if only in their imaginations. A sophisticated magazine – Holiday — was created to cater to their aspirations.

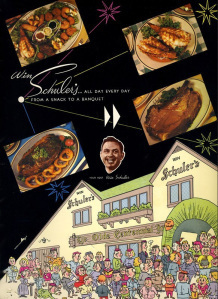

Holiday’s first issue came out in March 1946. A couple of months later Madison Avenue advertising man Ted Patrick took over as editor. A gourmet and bon vivant, Patrick gravitated toward fine restaurants. In 1952 the magazine began presenting awards to American restaurants that achieved dining distinction, recognizing 49 the first year. Among the winners were Bart’s (Portland OR), Commander’s Palace (New Orleans), Karl Ratzsch’s (Milwaukee), and Win Schuler’s (Marshall MI).

Holiday’s first issue came out in March 1946. A couple of months later Madison Avenue advertising man Ted Patrick took over as editor. A gourmet and bon vivant, Patrick gravitated toward fine restaurants. In 1952 the magazine began presenting awards to American restaurants that achieved dining distinction, recognizing 49 the first year. Among the winners were Bart’s (Portland OR), Commander’s Palace (New Orleans), Karl Ratzsch’s (Milwaukee), and Win Schuler’s (Marshall MI).

Winners tended to remain on the list, though it was not guaranteed. Win Schuler’s (still in business today) featured steaks, prime rib, and pork chops, and hosted 1,200 patrons a day at its Marshall location [see menu below]. In 1971 it won its 20th Holiday award, no doubt not its last..

Even if, as Harvey Levenstein writes in Paradox of Plenty, Holiday stuck to “safe, sound, and usually American” choices where “the steak, lobster, and roast beef syndrome … reigned supreme,” its recommendations carried weight and raised the seriousness with which many American diners and restaurateurs regarded restaurants.

To win, a restaurant’s offerings were supposed to compare to French cuisine. It’s hard to see how a steak-and-baked-potato place could do that, but plenty such restaurants won awards. On the other hand, many of the winners were French inflected, particularly in NYC. A quick scan of restaurants included in the 1976 Holiday Magazine Award Cookbook shows that nearly 25% had French names and many more specialized in French dishes.

To win, a restaurant’s offerings were supposed to compare to French cuisine. It’s hard to see how a steak-and-baked-potato place could do that, but plenty such restaurants won awards. On the other hand, many of the winners were French inflected, particularly in NYC. A quick scan of restaurants included in the 1976 Holiday Magazine Award Cookbook shows that nearly 25% had French names and many more specialized in French dishes.

What some thought was a bias for restaurants in NYC and, to a lesser degree, NY state prevailed until 1968 when California restaurants won as many awards as New York (even though the number of winners in San Francisco still lagged behind NYC, 17 to 25).

The overall volume of winners grew over the years, reaching over 200 by the mid-1970s. The numbers reflected the growth in dining out – and maybe the tendency of award programs to expand. In the beginning whole swaths of the country had nary a winner. Winners would boast that they were “the only” restaurant – for example, in Wisconsin, in the South outside of Florida, among Midwestern states, etc. But over time winners could be found in all parts of the country, requiring some adjustment in the meaning of distinction. Statements appeared saying that awards were not given solely to elegant places. As Patrick’s successor Silas Spitzer said, “Elegance has a certain value in making our judgment of restaurants – but it’s not essential.”

The overall volume of winners grew over the years, reaching over 200 by the mid-1970s. The numbers reflected the growth in dining out – and maybe the tendency of award programs to expand. In the beginning whole swaths of the country had nary a winner. Winners would boast that they were “the only” restaurant – for example, in Wisconsin, in the South outside of Florida, among Midwestern states, etc. But over time winners could be found in all parts of the country, requiring some adjustment in the meaning of distinction. Statements appeared saying that awards were not given solely to elegant places. As Patrick’s successor Silas Spitzer said, “Elegance has a certain value in making our judgment of restaurants – but it’s not essential.”

I suspect that the significance of the awards was greatest during Patrick’s editorship, which ended with his death in 1964. The magazine fell on hard times in the 1970s and was sold in 1977. Even earlier the awards were losing clout. Among those in the 1976 cookbook were several that had come under harsh criticism. Many specialized in “continental” cuisine which had lost its glamour by this time, or were considered uninspired. In 1974 John Hess wrote that The Bakery in Chicago and Ernie’s in San Francisco were “disappointing.” NYT critic John Canaday declared in 1975 that Le Manoir was the French restaurant where he had the worst meal in the past 20 months, Le Cirque the “worst restaurant in proportion to its popularity,” and the “21″ Club “least worth the trouble.”

The awards, called Travel-Holiday awards after Holiday’s 1977 merger with Travel, continued until 1989.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

April 14, 2013

Restaurant as fun house: Shambarger’s

I came across this restaurant while looking through lists of winners of Holiday Magazine awards. I was intrigued to learn that Shambarger’s, in the small town of Redkey, Indiana, was one of only five restaurants in that state to win such an award in 1972.

I came across this restaurant while looking through lists of winners of Holiday Magazine awards. I was intrigued to learn that Shambarger’s, in the small town of Redkey, Indiana, was one of only five restaurants in that state to win such an award in 1972.

As I learned more about Shambarger’s I had mixed reactions: fascination at its creator’s unstoppable spirit, surprise that it had won prestigious awards, and gratitude that I had never been compelled to sit through a 5- to 6-hour dinner and vaudeville show there.

For Shambarger’s fell into a category I call the fun house restaurant, once occupied by hotspots of enforced jollity such as Greenwich Village’s Village Grove Nut Club or the Beacon Supper Club in Denver whose owners put on funny hats to make people laugh [pictured]. La Nicoise in Washington, D.C. had waiters on roller skates.

For Shambarger’s fell into a category I call the fun house restaurant, once occupied by hotspots of enforced jollity such as Greenwich Village’s Village Grove Nut Club or the Beacon Supper Club in Denver whose owners put on funny hats to make people laugh [pictured]. La Nicoise in Washington, D.C. had waiters on roller skates.

Shambarger’s, adjacent to a railroad track, resembled an abandoned building on the outside, a junk shop on the inside. Its proprietor John Shambarger “performed” most of the seven-course dinner preparation in front of 50 or so guests who made reservations many months in advance, often traveled from afar, and paid about $100 a person in today’s dollars.

Making ten or more costume changes an evening, as a pirate, Tiny Tim, a Hawaiian dancer, etc., John chopped and mixed while singing, pattering, or loudly playing records keyed to each dish. Sometimes he told jokes, kissed women diners, or screamed ‘Aaayyyyy’ in people’s ears in concert with a Spike Jones record.

Making ten or more costume changes an evening, as a pirate, Tiny Tim, a Hawaiian dancer, etc., John chopped and mixed while singing, pattering, or loudly playing records keyed to each dish. Sometimes he told jokes, kissed women diners, or screamed ‘Aaayyyyy’ in people’s ears in concert with a Spike Jones record.

And all this without cocktails! No alcoholic drinks were served, except in later years when dinner began with punch bowl of “Bloody Redkey” made of tomato juice spiked with a Budweiser six-pack. Burp.

Holiday magazine’s volunteer judges in the 1960s and 1970s had a weakness for French cuisine. Which was what Shambarger’s provided, sort of. The menu was actually as jumbled as the decor of old clocks, menus, mirrors, lamps, and a moose head wearing a hat. It always included a main dish of Imperial Prime Ribs of Beef Flambee (in rum) and a dessert of sky-high strawberry pie (see above), but the first five courses varied. In one 1968 account they included – in a sequence that is perplexing – chicken soup, fresh fruit cup, corn fritters rolled in powdered sugar, shrimp, and guacamole with John’s special dressing.

Recipes for Shambarger’s guacamole and “Antique Salad Dressing” are furnished in the Holiday Magazine Award Cookbook (1976). I like guacamole and do not think it needs a dressing, especially not one made of cottonseed oil, vinegar, chopped onions, loads of sugar, catsup, concentrated lemon juice, and apple butter.

The restaurant had its fans and its detractors, but enough of the former to keep Shambarger’s in business under John’s management from 1959 until the early 1980s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

April 8, 2013

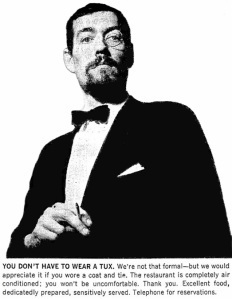

Dressing for dinner

In the vast majority of eating places customers never had to be told to “come as you are.” That’s how they were going to come – or else they weren’t coming at all. Farmers wearing overalls were likely to show up in small town cafes, while white collar workers in shirtsleeves grabbed seats in city lunchrooms.

Nevertheless, there was a segment of society that “dressed” for dinner. People of high society were accustomed to donning formal wear for dinner parties given in private homes. Then, as New York society began to expand beyond “the 400″ in the late 1890s, growing ranks of wealthy newcomers adopted formal dress for dinners in hotel dining rooms and swanky restaurants.

In the late 1890s men began to wear tuxedos for such outings. Women wore long gowns, cut lower than their daytime dresses. But the era of luxury dressiness was brief. After WWI, with prohibition forcing the closure of many fine restaurants and “lobster palaces,” more informal clothing became acceptable in most restaurants. [Rector's, 1913, illustrated] What was known as afternoon wear – coats and neckties for men and daytime dresses and hats for women – became the new standard. But even that dress standard tended to erode.

It isn’t as easy to enforce a dress code as it might seem. As long as a restaurant isn’t using a dress code as a foil for illegal discrimination, it can set the dress bar as high as it wants. But will customers constantly challenge it? Even worse, will they shun the restaurant entirely?

Rejection of the Café de l’Opera’s formal wear requirement was cited as one reason for its sudden demise in NYC in 1910. And the 1930s Depression encouraged a lower standard. After World War II some predicted a return to elegance, but that proved shaky. Many well-established fine restaurants struggled with turtleneck-wearing male guests in the 1960s and 1970s. At New York’s “21″ the maitre d’ developed a practice of requiring necktie-less men to put on a hideously garish tie that he provided. This had the effect of either making them (a) leave, or (b) feel so embarrassed they never dared come without a tie again. Other places relented and admitted guests in “dressy casual” wear.

A new restaurant wishing to enter the esoteric fine dining ranks, underwritten by a dining room of well-dressed guests, has to ask itself if it can pull it off. If it does not draw the “top-drawer” clientele it aims for it may find its dress code impossible to enforce. For instance, resorting to posting a “Dress Code for Ladies” notice near the front door, as a San Diego reviewer said of a restaurant there in 1981, is “simply tacky.” It is scarcely better than a sign reading “No shirt, no shoes, no service.”

A new restaurant wishing to enter the esoteric fine dining ranks, underwritten by a dining room of well-dressed guests, has to ask itself if it can pull it off. If it does not draw the “top-drawer” clientele it aims for it may find its dress code impossible to enforce. For instance, resorting to posting a “Dress Code for Ladies” notice near the front door, as a San Diego reviewer said of a restaurant there in 1981, is “simply tacky.” It is scarcely better than a sign reading “No shirt, no shoes, no service.”

Likewise, a restaurant may portray itself as elegant, on a postcard, publicity photo, or website, but rarely will the actual guests look quite so sophisticated as those pictured. And, needless to say, fancy dress does not in itself project elegance.

Today there is a small top tier of restaurants whose guests would not dare to wear shorts, t-shirts, baseball caps, or overlarge rubber-soled shoes. But, most restaurants are far more informal. Overall, “come as you are” – a phrase first used by churches — has remained in effect.

The phrase itself attained widespread use by restaurants in the 1960s when it appeared in advertisements for suburban establishments wishing to attract families. A new segment of chain restaurants came into being, a few notches less casual than fast food establishments, but entirely non-intimidating in their standardized cuisine, friendly service, and “fun” decor. Philip Langdon, in his book Orange Roofs and Golden Arches, sees the “chain dinnerhouses” as coming from the West (where restaurant dress rules were always more relaxed). Examples included Victoria Station, originating in San Francisco, and Steak & Ale, from Dallas.

At the present moment, at least, it is difficult to imagine a return to turn-of-the-century formality. I’d guess that even the 1% don’t like to dress up.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

March 30, 2013

Dining on the border: Tijuana

Borderlands are fascinating social and cultural mixing bowls. Their restaurants exemplify how variable these places can be. Lacking tradition as well as a local clientele and culture, there is little shaping them other than market forces. In Tijuana prominent historical factors shaping the market were drinkers’ desire for alcohol and restaurant owners’ need to recoup lost business.

Borderlands are fascinating social and cultural mixing bowls. Their restaurants exemplify how variable these places can be. Lacking tradition as well as a local clientele and culture, there is little shaping them other than market forces. In Tijuana prominent historical factors shaping the market were drinkers’ desire for alcohol and restaurant owners’ need to recoup lost business.

The history of restaurants and cafes in Tijuana is marked by all the instability and calamity that the restaurant business is known for – and then some! Partnerships shifted, scandals erupted, and fires swept through the main street, Avenida Revolucion.

When Prohibition became the law in the United States, a number of San Diego restaurant, café, and bar owners – Italians, Jews, Slavs, and others — set up shop a stone’s throw away, in Tijuana, then a village of little more than 1,000 people. American visitors who began to head there did not go to soak up Mexican culture, but to escape restraints [see 1922 advertisement above]. Tourist eating places, all furnishing drinks and often entertainment, had names like Johnny’s Place, Aloha [American teens in Aloha Cafe, 1940s, below] , and Alhambra. Few were run by Mexicans and Mexican food ranked low on the culinary scale.

From the point of view of San Diego’s anti-alcohol, cafeteria-loving reformers, the drinking, gambling, and prostitution that went on in Tijuana made it a hell hole. Tijuana’s reputation, of course, did not stop everyone from going there, even many respectable, well-off San Diegans and Los Angelenos, as well as civic organizations. Determined to limit vice, prohibitionists waged vigorous battle to restrict passage by shortening border crossing hours, finally succeeding in closing the border from 6 pm to 6 am in 1926.

Despite the curfew, San Diego’s hotel and restaurant industries protested in 1931 that the 6 pm closing “ha[d] not prevented one single person from going to Tijuana,” and had actually reduced their business by 25%. They alleged that visitors went for the whole day or stayed overnight, enabling them to engage in more drinking, gambling, or whatever than previously. Tijuana flourished, opening more cafes, clubs, and hotels.

The better restaurants specialized in “international cuisine” which consisted mainly of steaks and seafood along with Italian, French, German, and Mexican dishes. In this category were restaurants variously operated by Alex and Caesar Cardini of salad fame. Julia Child wrote in her 1975 book From Julia Child’s Kitchen that she remembered going to Caesar’s for lunch in 1925 or 1926 with her parents. They had heard of his special salad and were eager to taste it. “Caesar himself rolled the big cart up to the table, [and] tossed the romaine in a great wooden bowl,” she wrote.

The border curfew was relaxed in1932 and lifted entirely in 1933. But if that had an adverse impact on Tijuana tourist trade, it was nothing compared to the blows delivered by the repeal of U.S. Prohibition in 1933 and a Mexican gambling ban in 1935. Tijuana bartenders correctly predicted few bars and cafes would survive. Sure enough, proprietors headed back to the U.S. Caesar Cardini opened a place in San Diego in 1936.

The tourist economy waxed and waned thereafter, thanks to such things as the 18-year-old drinking age, the availability of marihuana, and incidents of violence. Mexican cuisine became more popular in Tijuana’s tourist district in the latter 20th century. Richard Nixon, then Vice President of the United States, ordered Mexican dishes and German beer in an informal visit to the Old Heidelberg there in 1960.

Today Tijuana is a large global city, yet Americans tend to stick to the main tourist avenue as of old. There is a diversity of restaurants, many with Hispanic names and owners. Caesar’s has continued, off and on, since the Cardinis departed. Yet, as much as I’d like to believe a recent comment about it on TripAdvisor.com (“nice place to feel the real culture and history of Tijuana”), I have to ask, “Real culture? Real history? What?”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

March 19, 2013

Postscript: beefsteak dinners

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Armory Show, an art exhibit that introduced Americans to modern art, most notably to Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase [No. 1]. Last week I received a copy of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art Journal which commemorates the show. To my surprise, the journal contains an article (Meat and Beer, by Darcy Tell) about a beefsteak dinner given by the artists who organized the Armory Show in gratitude to the press whose extensive coverage helped make the show a popular success.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Armory Show, an art exhibit that introduced Americans to modern art, most notably to Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase [No. 1]. Last week I received a copy of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art Journal which commemorates the show. To my surprise, the journal contains an article (Meat and Beer, by Darcy Tell) about a beefsteak dinner given by the artists who organized the Armory Show in gratitude to the press whose extensive coverage helped make the show a popular success.

The Armory Show was largely organized by American artists Walt Kuhn, Arthur Davies, and Walter Pach. (Kuhn’s and Pach’s papers are preserved in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

In an earlier post I wrote about beefsteak dens, dungeons, and caves where men put on butchers’ aprons and threw aside the trappings of civilization. Sitting uncomfortably on boxes in dingy cellars, they drank beer and ate steaks without silverware or napkins.

The 1913 Armory Show dinner was held at Healy’s restaurant, on 66th Street in NYC, a popular place for these feasts. It had three rooms dedicated to them: the Dungeon, the Jungle Room, and the Log Cabin Room. The artists and their “friends and enemies from the press,” as they were designated on the menu, gathered in the Log Cabin Room, probably the most civilized space of the three, furnished with long tables and chairs and complete with tablecloths and napkins. While the guests ate, someone read aloud humorous, insiderish (fake) telegrams, even one purporting to be from Gertrude Stein [see link below].

The 1913 Armory Show dinner was held at Healy’s restaurant, on 66th Street in NYC, a popular place for these feasts. It had three rooms dedicated to them: the Dungeon, the Jungle Room, and the Log Cabin Room. The artists and their “friends and enemies from the press,” as they were designated on the menu, gathered in the Log Cabin Room, probably the most civilized space of the three, furnished with long tables and chairs and complete with tablecloths and napkins. While the guests ate, someone read aloud humorous, insiderish (fake) telegrams, even one purporting to be from Gertrude Stein [see link below].

I have to admit I was a tiny bit disappointed to learn that such a (presumably) sophisticated group of men as was represented at this dinner would choose to attend a beefsteak at Healy’s. By 1913, if not long before, beefsteaks were recognized as evenings of orthodox jollity for business men and conventioneers. Yet, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors paid out $234 [at least $5,500 today] for a dinner much like that enjoyed by the Paper Box Makers Association and the League of Associated Hat Men.

And, just like the hat men and box makers, they took away a regulation group photo to show for it.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

March 13, 2013

Three hours for lunch

For every devoted restaurant-goer who likes to keep up with the latest restaurant trend there are probably two others who would prefer an eating place from the past. Despite my fascination with the history of restaurants, it might surprise some readers to learn that as a diner I am not attracted to historic restaurants; I study the past but eat in the present. Journalist and author Christopher Morley, however, might have been the patron saint of those who would gladly flip back the calendar when dining out.

For every devoted restaurant-goer who likes to keep up with the latest restaurant trend there are probably two others who would prefer an eating place from the past. Despite my fascination with the history of restaurants, it might surprise some readers to learn that as a diner I am not attracted to historic restaurants; I study the past but eat in the present. Journalist and author Christopher Morley, however, might have been the patron saint of those who would gladly flip back the calendar when dining out.

Through the 1920s he gathered together friends who loved to explore the corners, alleys, and waterfronts of Manhattan and environs, especially Hoboken which he christened the “seacoast of Bohemia.” Their whimsical jaunts centered on a leisurely lunch.

The group, whose personnel was always changing, was made up of men who had enough time to join Morley’s Three Hours for Lunch Club. He initiated it in 1920 when he began writing a column for The New York Evening Post called “The Bowling Green” that chronicled his explorations of New York and the escapades of the club. Later the column appeared in the Saturday Review of Literature.

The club was less about food than about male camaraderie, conversation, and humorous one-upmanship. In earlier times, before Prohibition, it might have been a drinking club. The loss of masculine drinking culture and the alleged feminization of restaurants underwrote a lament for a present era supposedly ruined by women lunching on sandwiches and soft drinks at soda fountains. By contrast, Morley & Co. searched out old-fashioned taverns and chop houses.

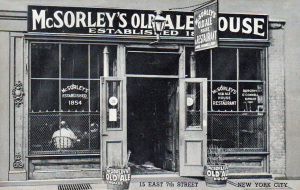

He wrote in a tribute to McSorley’s Ale House (which did not admit women until 1970), “Atrocious cleanliness and glitter and raw naked marble make the soda fountain a disheartening place to the average male. He likes a dark, low-ceilinged, and not too obtrusively sanitary place to take his ease. At McSorley’s is everything that the innocent fugitive from the world requires.”

He wrote in a tribute to McSorley’s Ale House (which did not admit women until 1970), “Atrocious cleanliness and glitter and raw naked marble make the soda fountain a disheartening place to the average male. He likes a dark, low-ceilinged, and not too obtrusively sanitary place to take his ease. At McSorley’s is everything that the innocent fugitive from the world requires.”

Without his male buddies, Morley might have been limited to the company of his wife Helen, whom he called Titania in his columns. Although the pair enjoyed frequent Saturday lunches in the basement of Moretti’s table d’hôte on East 14th Street, he complained publicly, “Anyplace that I think is peculiarly amusing, or quaint, or picturesque, Titania thinks is unhealthy. Sometimes I can see it coming. We are on our way to Mulberry Bend, or the Bowery, or Farrish’s Chop House. I see her brow begin to pucker . . .”

The club, which included Don Marquis, sea captain/writer David William Bone, Sinclair Lewis, and other editors and writers, flourished about the same time as the Round Table whose literary stars met at the Algonquin Hotel. For a time before he founded his own club Morley was part of a group of Vanity Fair writers who congregated at the Café Noir, but he felt edged out because he lacked the Vanity Fair style. “Even Thackeray would have been grayballed,” he wrote later.

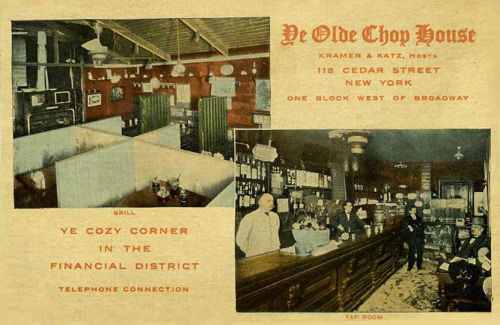

A favorite THFL place in lower Manhattan was Ye Olde Chop House on Cedar Street (pictured pre-Prohibition with sawdust floors beloved by CM) where the club named a waitress “the Venus of Mealo.” The cuisine of chop houses, as might be expected, featured grilled meat and homey dishes such as pickled beets, corned beef hash, tapioca pudding, and rhubarb pie. Far from seeking adventure in the culinary department, Morley once ordered swordfish steak, but declared it “too reptilian.”

Other than the musty hangouts of lower Manhattan, Hoboken’s Hofbrau, Meyer’s Restaurant, and the American Hotel were popular with the club. In 1929 Morley and others bought a bankrupt ironworks on River Street in Hoboken to become club headquarters. But it seems the club was waning around this time and it’s not clear how long that experiment continued. Three-Hours-for-Lunch was succeeded by another club, the Baker Street Irregulars, which Morley – a Sherlock Holmes fan – formed at Prohibition’s end.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

February 27, 2013

Light-fingered diners

If the number of newspaper stories is a reliable index to a trend, then a fad for stealing small items from restaurant tables began in the 1890s. Its continuing incidence is perhaps one reason why table appointments gradually became far less elegant and costly.

If the number of newspaper stories is a reliable index to a trend, then a fad for stealing small items from restaurant tables began in the 1890s. Its continuing incidence is perhaps one reason why table appointments gradually became far less elegant and costly.

A flurry of stories appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries about affluent society people who “collected” cordial glasses, demitasse cups, salt cellars, silver spoons, oyster forks, and nut picks as “souvenirs” of first-class hotel dining rooms and restaurants. Anything small that bore an insignia from an elite establishment sent out an irresistible message: “Take me home with you.” Or, as a NYC restaurant owner would confirm decades later, “Put a spoon on a table with a fancy crest on it and kiss it goodbye.”

The “thieves” – a term pointedly avoided by all – were usually identified as young women from the best families, though men were also known to freely pocket alluring items. It was especially attractive to pick things up while traveling. Women would display their booty in cabinets with little ribbons and tags that gave the date and occasion that each bibelot commemorated.

The “thieves” – a term pointedly avoided by all – were usually identified as young women from the best families, though men were also known to freely pocket alluring items. It was especially attractive to pick things up while traveling. Women would display their booty in cabinets with little ribbons and tags that gave the date and occasion that each bibelot commemorated.

How cute! A little less cute, though, were college student pranks following athletic competitions. A gang of Amherst College students met with suspension after they raided three railroad restaurants on the return train trip from a Dartmouth football game in 1893. During their “wilding” episode they descended en masse on three successive Vermont depot restaurants, making off with everything they could grab from sandwiches and ginger ale to dishes and spoons to remind them later of their escapades.

Typically souvenir hunters were portrayed as feeling not the least bit guilty about their some-would-say-larcenous activities. “I must steal one of those lovely things,” said a woman at a fashionable restaurant. Her friends merely laughed. Another received encouragement from her luncheon companions when she declared she wanted to snag a silver match case for her husband. “So she tucked it in her muff and went out with the glee of a smuggler,” the story relayed.

Often these activities brought forth a degree of censure among reporters and readers. Was it not true, for instance, that these same people would probably condemn a poor man for stealing food? Was it really a victimless crime? Didn’t waiters have their small wages docked for missing silver?

The moral code, such as it was, decreed that stealing from need was a crime, but stealing something you didn’t need or could easily afford to pay for was not a crime. Plus, as much as restaurateurs hated it, who wanted to accuse wealthy guests of stealing? Prosecution, or even confrontation, was rare though sometimes additional charges – curiously hard to read – were levied on a check. Over time menu prices crept up to cover shrinkage, tableware became ordinary, and peppermills grew monstrous.

The moral code, such as it was, decreed that stealing from need was a crime, but stealing something you didn’t need or could easily afford to pay for was not a crime. Plus, as much as restaurateurs hated it, who wanted to accuse wealthy guests of stealing? Prosecution, or even confrontation, was rare though sometimes additional charges – curiously hard to read – were levied on a check. Over time menu prices crept up to cover shrinkage, tableware became ordinary, and peppermills grew monstrous.

We’d probably hear more on this subject, particularly on the diverse range of things taken from restaurants, but restaurant managers prefer to keep silent. As one confessed in 1976, “We don’t like to talk about this sort of thing. It only gives the public more ideas.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

February 19, 2013

Mind your manners: restaurant etiquette

When etiquette manuals address manners in restaurants they are usually discussing first-class restaurants since that is where people are at their most self-conscious and insecure. Cheap, casual restaurants, on the other hand, have been understood as living museums of what not to do, presumably being filled with patrons who are perfectly content to slurp their coffee, eat off their knives, tuck napkins under their chins, and chew on toothpicks.

When etiquette manuals address manners in restaurants they are usually discussing first-class restaurants since that is where people are at their most self-conscious and insecure. Cheap, casual restaurants, on the other hand, have been understood as living museums of what not to do, presumably being filled with patrons who are perfectly content to slurp their coffee, eat off their knives, tuck napkins under their chins, and chew on toothpicks.

For many people, middle-class women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, the notion of eating among strangers required some getting used to. Although etiquette at its most basic means being considerate of the feelings of others, it is clear that much advice was meant to make female readers themselves at ease in restaurants.

Anxiety started at the point of entry. Walking through a restaurant toward a table was agony for some women. As a woman writer in American Kitchen Magazine remarked in 1899, “Even today it is a severe trial for many women, and some men, to enter a hotel dining room and particularly hard if it must be done without a companion. Some that march in with boldest front and utmost nonchalance are but actors, trembling within while brave to outward seeming.”

As a result of discomfort about walking to a table, for years etiquette books and columns seemed preoccupied with this subject. All agreed that when the headwaiter beckoned, the woman of the duo should go ahead of her male companion. I would think that would have made women even more uncomfortable but perhaps the ruling of etiquette mavens relieved the stress of uncertainty. Horrors, the man is going first in the above illustration.

As women went to restaurants more often, things began to change. Young women grew restless at the confinement of propriety which required that they could not go out with a man without a chaperon, could not drink wine, and should only pick at their food. How shocking that they began to have fun, devour their dinners with enthusiasm, and lean their elbows on the table!

As late as 1915, though, women were still being advised to let the man do the ordering and not to even look at the menu unless he suggested it. As for the bill, heaven forbid she should view it: “A woman makes a point, always in restaurants, of not seeing the check when it is brought by the waiter, and while the man is getting out the money to pay it she should keep her gaze from it.”

If the 1917 novel The Rise of David Levinsky is at all representative, ambitious immigrants also wanted advice on restaurant-ing. In it David admits that on his first visit to a high-class restaurant with a business associate, “The occasion seemed to call for a sort of table manners which were beyond the resources . . . of a poor novice like myself.” He confesses ignorance to his kindly companion who agrees to tutor him on how to order, use a napkin, eat soup, fish, and meat and “what to do with the finger bowl.”

Conservative advice continued to be issued in the 1920s, such as Emily Post’s 1923 dictum: “Absolutely no lady (unless middle-aged – and even then she would be defying convention) can go to dinner or supper in a restaurant alone with a gentlemen.” But the Depression and World War II eras were about to have the effect of relaxing American customs.

Still, even today many people have questions about how to act in a formal restaurant setting. As for how to handle bread, break it into pieces and butter each piece individually before eating it. And what if you drop a fork? Ask the server for another. Personally, I truly wish more people would follow this 1904 counsel: “Private affairs should not, ordinarily, be discussed in the public dining room, but if they are, a low tone should be used.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013