Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 2

May 19, 2025

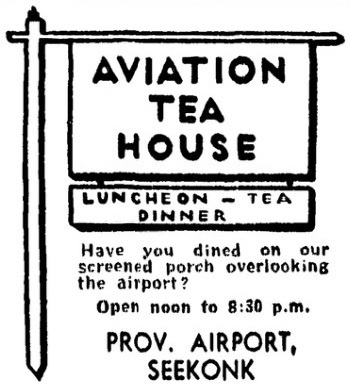

Find of the day: Aviation Tea Room

This past weekend at the giant Brimfield flea market I found the charming small menu shown above and below.

The menu is for a tea house that operated seasonally from 1928 through 1940. I’m guessing it may date from the mid-1930s since the prices match those in an advertisement from 1937 [shown below].

I couldn’t determine if the Providence Airport owned the tea house, renting it to the two women who ran it, or if the women were the owners. Despite the airport’s name, both it and the tea house were actually located in Seekonk MA, 7 miles from Providence RI.

The air field was private, offering flying lessons, short touring flights, and airplane storage. Its owners also sold the newly developed Aeronca monoplane.

The two women who ran the tea house for most of its years, Mildred Burrell and Lyle Lincoln, were from Fall River MA. They seemed to enjoy the status of socialites, being free to pursue that lifestyle in the months they were not running the tea house. They were able to make a success of the business for at least 10 years, which was greater than the lifespan of most eating places. It was offered for sale in 1939, but its new operator only kept it open for a year.

According to a 1932 feature story about women and aviation, women had no place in the early days of aviation, and were not expected to ever become passengers. However, that had changed by the time of the story when they had begun to learn to fly, and made up an increasing percentage of passengers and in-flight hostesses. According to the story, the operators of the tea house had made “occasional flights, [but] neither has a license or even any interest in obtaining one.”

Various newspaper stories of groups patronizing the tea house suggest that most came from Providence. Patrons could watch the airfield’s activities, but how many of the field’s plane owners, tour takers, or students taking flying lessons patronized the tea house is uncertain. Yet this 1929 advertisement suggests that there may have been some interest in an air tour followed by dinner on weekends.

By the time the tea house closed after the 1940 season, public airports were well established, and many featured full-scale restaurants that drew the public to dine while watching planes take off and land.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

May 11, 2025

Restaurant-ing on Mother’s Day

Beginning in the 1950s going out for brunch or dinner began to be a popular way to treat mothers on their annual holiday. But it seems to have lost its appeal somewhat in recent years. Has the idea of doing that waned with the public or is it because fewer restaurants are open on Sundays? Maybe restaurant staffs would like to celebrate the day themselves. But it is more likely that going out to eat on Sundays, once very popular, has become less so and restaurants don’t find it worthwhile to stay open. And, could it be that brunch has lost its appeal as well? [Above: Allgauer’s ad, Chicago, 1956]

April 27, 2025

Music & food at Café Society

Café Society was the satirical name of a New York jazz club in the late 1930s and 1940s. The name was meant to make fun of people who wanted to be seen as sophisticated rather than merely rich. However, it’s likely that Café Society nevertheless proved to be an attraction to many of those same people.

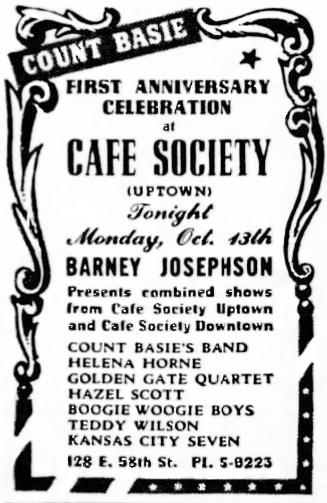

By the second year there were two locations of Café Society, Downtown and Uptown. The clubs and their owner Barney Josephson have become well known for the number of jazz greats they introduced and nurtured, among them Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, and Teddy Wilson. And also for their full acceptance of Black customers.

Unlike other “café society” club owners such as the Stork Club’s, Josephson refused to accept the racial codes of that time. He was determined not to follow policies that featured Black performers but would not allow them to mingle with the patrons, and excluded Black guests. Even when these policies began to soften, it was common for Black patrons to be seated inconspicuously in the least desirable spots. [Above: 1939 sign at the Downtown club ridiculing prominent society figures]

When he opened the Downtown Greenwich Village club in late December 1938, Barney recruited three musicians who had been part of a Carnegie Hall Christmas Eve program called From Spirituals to Swing. Albert Ammons, Meade Lux Lewis, and Pete Johnson performed at the club a few days later. The club advertised that it featured “boogie-woogie,” which was largely unknown in New York City at the time. [Above: Downtown in 1939; William Gropper mural]

But what about the food? In general, jazz clubs’ culinary output has not been regarded as the finest. Barney claimed that when he started out, most jazz clubs were run by mobsters who didn’t even try to prepare good meals. He tried to do better, but it’s hard to judge how well he succeeded since I’ve found little commentary. Club cuisine wasn’t usually written about.

In a book based on recordings of his memories, published by his fourth wife after his death, Barney commented that in most nightclubs waiters were urged to push drinks not food. For the Uptown Café Society (on East 58th), opened about a year later than Downtown, he made an effort to provide good food by hiring a chef who had managed the Claremont Inn and had been head waiter at Sherry’s. Robert Dana, nightclub editor of the Herald Tribune, was of the opinion that “On its food alone, Café Society ranked with many fine restaurants,” singling out squab chicken casserole and cream of mushroom soup. [Above: Uptown, 1943; Below: Advertisement with the musical lineup on Uptown’s first anniversary, 1940]

By the end of 1947 Uptown was out of business, and Downtown closed in early March of 1949. The problem was that Barney’s brother Leon, an admitted Communist Party member, was part owner of the clubs, having advanced start-up money. In 1947 Leon was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, refused to testify, and spent a year in prison. Barney was seen as guilty by association, attendance at his clubs plummeted, and he lost all his money. It seemed his career as a jazz club owner was over.

After that he concentrated on the restaurant business. He opened three restaurants, all called The Cookery, with one on Lexington across from Bloomingdale’s, one on 52nd Street in the CBS building, and then in 1955 a third one in Greenwich Village on University Place and 8th Street. The first two did not stay open long, but the Greenwich Village site was successful. [Above: The Cookery on Lexington; wall art by Anton Refregier]

While the two Café Societies had featured jazz with food, his third Cookery was to become a purveyor of food with jazz.

The Village’s Cookery was far from glamorous, generally described as “a hamburger, ham-and-egg type restaurant.” For the first 15 years there was no music. And then one day Barney had a visit from pianist Mary Lou Williams — who had played at Café Society Downtown – looking for work. As he described it:

“. . . this lady, one of the greatest musicians of all times, composer, arranger, not working? It was all this wild, crazy rock. . . . I investigated and found out I didn’t need a cabaret license in my place if I only had three string instruments.” [Above: Mary Lou Williams, at the Cookery in the Village, 1970]

So he told her to go rent a piano and, presto!, he was back in the jazz club business as of 1970. She was a draw. As he put it, “Mary returned to The Cookery each year through 1976 for three-month gigs, always to critical acclaim and crowds.” Other musicians who played there included Teddy Wilson, Marian McPartland, and the elderly singer Alberta Hunter, who had been working as a nurse.

The Cookery stayed in business until 1984.

For those interested in reading more about Barney’s clubs, see the book based on his recorded memoir published by Terry Trilling-Josephson in 2009 (Café Society: The wrong place for the Right people).

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

April 13, 2025

Catering to women’s tastes

In the 19th century and much of the early 20th restaurant owners viewed women’s tastes as quite different than men’s.

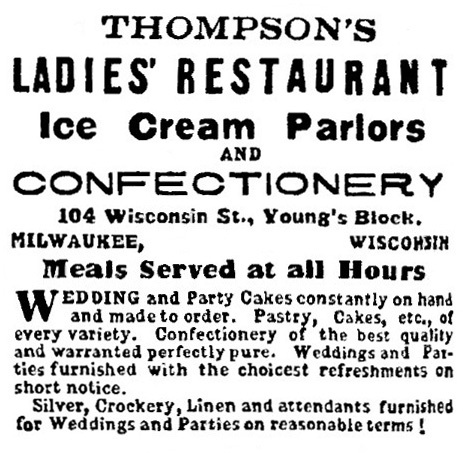

Women did not patronize restaurants to a great extent in the 19th century, but it seems when they did they preferred places that furnished ice cream, pastries, and cakes, not only for immediate consumption but also to order for the home. For instance, in 1865 in Milwaukee WI there was Thompson’s Ladies’ Restaurant, Ice Cream Parlor, and Confectionery which provided three meals a day plus Tea, along with Wedding and Party Cakes to order. [Advertisement shown below]

Such places were seemingly rare and I doubt that their customers included women of little means. In 1869, it was reported that poor working women frequented “coffee places” where they ordered simply bread or cake with coffee. But even these may have introduced the long-lasting idea that women were particularly fond of sweet foods.

I wonder if it was often the case that they made do with a simple sweet dish because that was all they could afford.

Of course, sweet dishes were not women’s only preferences if they could pay more. Oysters were also popular choices — as they were with men.

Commentary about women’s food preferences was sometimes insulting. The idea seemed to be firmly planted for decades and well into the 20th century that women were frivolous eaters while men chose real food. That would be repeated time and time again in books and newspaper stories. For instance:

1888, New York Tribune: In ladies restaurants a woman might order salad, ice cream, oyster patty, eclaire, cheese cake, “and perhaps one or two other varieties of whipped froth and baked wind.”

1894, Charles Ranhofer cookbook: “Should the menu be intended for a dinner including ladies, it must be composed of light, fancy dishes with a pretty dessert; if, on the contrary, it is intended for gentlemen alone, then it must be shorter and more substantial.”

1917, Housewives Magazine: a woman “expert” reported that men made “habitual food choices” while women “go by eye-appeal.” Typically, she explained, almost all men ate meat, while women preferred fruit salad, beans or macaroni, and cake and ice cream.

By the mid-1920s women were making up a larger proportion of restaurant goers than ever before, possibly as much as 60%. Pleasing them was becoming essential. The trade magazine Restaurant Management advised: “Many managers have not yet seen the light. If you doubt this watch the places that get the women’s trade. In the majority of cases these restaurants serve light, tasty foods in homelike surroundings and at a reasonable price “

But even as women’s patronage became important, there were still commentaries that were insulting. Eating habits were changing, possibly due in large part to Prohibition, leading the former proprietor of Keen’s Chop House in NYC to comment in 1931: “Formerly when a man took a lady to dinner he not only selected the restaurant, he took great pride in ordering a particularly choisi, well-balanced meal.” But, he said, it had become clear that now women “would rather have had the unholy hodgepodges you see them reveling in to-day.”

Even some women criticized women’s food choices. In 1937 a woman who had worked for major restaurant chains said that to succeed in the Depression tea room operators had to recognize that men wanted “real food” . . . not “Canary bird food.” [Above: Boston tea room’s “canary bird food.”]

Slowly, insults concerning women’s tastes died down, although differences in restaurant orders based on gender were still observed. In 1934 a woman tea room operator said that “The conventional woman’s taste runs to chicken patties, peas, and ice cream; men like steaks, French fried potatoes, and apple pie.”

Had differences largely disappeared by the 1950s? When I wrote an earlier post I thought that numbers of men still wanted what they regarded as he-man meals and that there were restaurants willing to cater to them.

Yes, a chef commented in 1952, there were those who still believed that men preferred “an exclusive diet of thick mutton chops, brawny steaks, large ribs of beef and mountainous apple pies” while women went for “chicken patties, asparagus points and meringue shells.” But he declared this false, saying in his experience women “want their double sirloins as big as those served to their husbands,” while the most popular choice at a NY men’s club was “creamed chicken with sherry,” despite the fact that the chicken was cut up into small chunks.

But there may still have been some resistance on the part of men about eating foods tagged as feminine. Salads are one example, a favorite with women since the 19th century, but not so much with men. That included meat and fish salads, and in more modern times, green salads. And an industry publication reported in 1960 that a large hotel lured men into ordering a sandwich by naming it “The Mountain Climber.” It was made of turkey, ham, and cheese and had been previously ordered only by women.

However, as much as the differences in the restaurant orders of men and women may have declined in the late 20th century, it seems that with a few exceptions women still haven’t achieved equal stature or full recognition as gourmets or culinary pace-setters.

I’d love to hear readers’ thoughts on this topic.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

March 30, 2025

Ruth Stout, her life and tea rooms

A few days ago I read a fascinating article by Jill Lepore in the New Yorker. It was about Ruth Stout, author of How to Have a Green Thumb, Without an Aching Back, originally published in 1955. It has been reissued and is still quite popular.

There were many engaging aspects to Stout’s life, such as her affair with the radical Scott Nearing, her career as a writer, the fact that her brother was the mystery novelist Rex Stout who created Nero Wolfe, her involvement with ‘no-plow’ gardening, and the fact that lived to be 96. [Below: Ruth in 1923, age 39.]

But what especially interested me was that Stout had been briefly involved in owning and running two tea rooms in Greenwich Village around 1917. They didn’t last long, but that was true — almost typical — of many tea rooms.

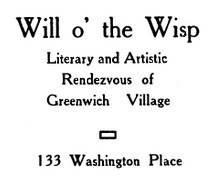

The first was the Will o’ the Wisp which she opened with a family friend. It was appropriately named, being short-lived. It was ridiculed by the New-York Tribune in a 1917 story about an imaginary visitor from afar searching NYC for the “real Bohemia.” He and the writer go to “the Wisp” (as it was known), where the “young ladies” (actually about 32 and 50 years old) that operated it invite them to come back the next night and help wash dishes around 1 or 2 a.m. The sardonic piece ends with the trite observation that Bohemia is a fantasy.

If the Tribune writer had known that the two women running the Wisp were both from small towns in Kansas, that would have been another sign of how misplaced his dismissive attitude was. They actually represented the adventurousness and talent of many New York transplants. In this case they were writers, world travelers, and free spirits.

The Greenwich Village tearooms before World War I served mainly as hangouts for local residents, many of whom were artists and who liked to gather with friends in the evening. Alas, they didn’t spend much, so the advent of visitors from outside the Village was a financial boon. The Wisp tagged itself in advertising as a place for writers, “the poets’ favorite,” not a slogan likely to draw the masses.

As the photo at the top shows (by the Village’s photographer Jessie Tarbox Beals), tea rooms were plentiful, with three in the building in this photo. And the building itself is none too impressive, even looks somewhat structurally unsound. The Wisp is on the ground floor.

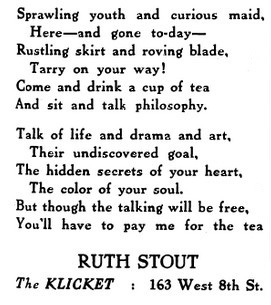

Not much later, or maybe simultaneously with the Will o’ the Wisp, Ruth opened a second Village tea room called The Klicket, this one with dancing. The Quill, the Village’s magazine, promoted it saying, “Ruth Stout’s ‘Klicket’ has a good floor, and say! Ruth CAN cook!” No doubt she was amused by that since she wasn’t much of a cook.

At the Klicket, Ruth found herself keeping even later hours, but there was little monetary reward.

As she indicated in her advertisement she mainly hoped her customers would end the evening by paying for their tea. It was not a financial success and she kept it going only for about a year.

In a 1917 book about the Village, author Anna Alice Chapin outlined the “phases” which the Village was going through, which included not only “the tea-shop epidemic,” but also psychoanalysis, arts and crafts, masquerade balls, and support for labor activism and anarchy. Ruth took up the call to radicalism. She and Rex were on the editorial board of a leading socialist-communist periodical The New Masses. She also visited Russia as a Quaker volunteer helping alleviate famine there in 1923 and became a helper and romantic partner of Scott Nearing for several years, living with him on his farm.

She published four books in the 1950s and 1960s, including her garden book and Company Coming: Six Decades of Hospitality, Do-it-yourself and Otherwise, in which she mentioned her tea rooms. Until her death in 1980 she spent her elder years in Connecticut where she and her husband Fred Rossiter had acreage.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

March 16, 2025

Exploding restaurants

After prohibition ended gangsters were in search of a new game. It didn’t take much time to discover the solution, in fact it was already in progress in Chicago by the late 1920s. [Above, Howard Johnson’s, Chicago, 1954]

As I mentioned in an earlier post on rackets, the new game involved getting protection money from weak sectors of the economy, namely businesses that had low-paid workers such as, but not limited to, restaurants. Unions wanted to recruit the workers but owners resisted. One solution seemed to be a bombing campaign that would soften the owners’ resistance. Some unions hired hoodlums to do the deed.

According to an account by Louis Adamic in his classic 1931 book Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America, workers wanting better pay and shorter hours were threatening to strike. The racketeers, according to Adamic, began to “‘muscle’ their way into the union offices and affairs, and in not a few cases took over the control of the organization.” The racketeers made more money and the unions thrived, at least in terms of growing membership.

To avoid the bombs, restaurant owners also paid gangsters protection money. If not, a bombing campaign might begin, perhaps starting with a weaker bomb, maybe a “stink bomb” or a mild explosive. If those didn’t work, it escalated to dynamite, resulting in heavier structural damage.

Often the bombings occurred late in the night or very early morning, but at other times, especially when stink bombs were used, it was during business hours. Even a stink bomb could put a restaurant out of business, since frequent customers, whose clothes might be ruined in the episode, would probably never return. Plus the restaurant could get a bad reputation. [Above, “humorous” letter sent to a newspaper in 1963]

Although workers unionized at numbers of restaurants in the 1920s and 1930s, especially in New York and Chicago, it’s not clear how much they benefitted. There is no doubt that they needed better pay and shorter hours. Many were working 12-hour days for very low pay.

Sometimes minor improvements did occur. A 1937 trial in NYC showed that if a restaurant owner chose to pay for protection against the mob there was one set monthly fee, but a lower one “if he contracted for increases of 50 cents or $1 a week for his workers and signed a closed shop contract,” that is, hired only unionized workers.

Famous New York restaurants such as Lindy’s were assessed with lower fees for joining protection plans because their fame helped persuade other restaurants to cooperate. A number of New York City restaurants resisted and were bombed., including Childs on 43rd street, many cafeterias, Park Lane, Ye Eat Shoppe, Rectors, Eatomat, Silver Dollar and Marine Grill, and Grant Lunch. Of course, there were many more.

New York succeeded in calming gangster infiltration (to what degree is unclear), but in Chicago it continued in restaurants into the 1970s. Union membership declined, but restaurant owners were still threatened and bombed, with racketeers seeking payment to make it stop.

Invariably, Chicago restaurant owners declared that they had no idea whatsoever about who had bombed them or why. More surprisingly, police also seemed strangely mystified. Very few bombers were ever caught or convicted. [Above, the owner of Wilkos in the Chicago suburb of Berwyn is comforted after 1964 bombing of his restaurant]

In 1964 Chicago Daily News columnist Mike Royko reported that the Illinois Fire Marshall William Cowhey said he was puzzled about what was going on. During a press meeting, Royko wrote, “Cowhey’s eyes squinted, as if he were peering into the distance for something. ‘The . . . rhyme . . . or . . . the . . . reason,’ he said, slowly. ‘If we could . . . get . . . the . . . rhyme or . . . reason.” In another column Royko explained, “The duties of the fire marshal included going to the restaurant, viewing the gaping hole in the door, the shattered windows, the rubble in the street, and announcing to newsmen: ‘This is arson.’ This job out of the way, it is the fire marshal’s duty to crouch and pick up a piece of rubble and stare at it so a picture can be taken.” [Above, owner inspects damage at his Ivanhoe restaurant in Chicago, 1964]

Although union membership and racketeering had declined by the 1980s, protection shakedowns, sometimes involving bombs, continued in that decade, and possibly still occur today.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

March 2, 2025

Famous in its day: Fanny’s

Lately I’ve been browsing through The Ford Treasury of Favorite Recipes from Famous Eating Places published in 1950. [illustration from Ford Treasury]

Among the 245 restaurants featured in the book, one stood out. Only Fanny’s gave no recipe. Instead, the ingredients of its salad dressing were simply listed. They were oil, tarragon vinegar, chutney, brown sugar, salt & pepper, mustard, fresh tomatoes, tomato paste, orange juice, ground pecans, garlic, onions, celery, and parsley.

The reason given was that the recipe was a valuable asset for which the owner Fanny Lazzar had been offered as much as $10,000. It was a “secret” recipe which, along with the restaurant’s spaghetti sauce, was closely guarded. The trademark had been registered in 1946.

Through the years the amounts said to be offered for the recipe increased mightily. In 1958 it was up to $250,000 according to the book Who’s Who — Dining and Lodging. (Oh, and it just happened that Fanny Lazzar was on the Advisory Board of Directors of the Who’s Who Historical Society that published the book.)

Fanny Lazzar of Fanny’s Restaurant serving her customers, A. Victor Abnee Jr. and Col. Robert Heuck, October 23, 1962 in Evanston, Illinois.

Fanny Lazzar of Fanny’s Restaurant serving her customers, A. Victor Abnee Jr. and Col. Robert Heuck, October 23, 1962 in Evanston, Illinois.The more I learned about Fanny Lazzar and her restaurant, the more I began to realize how much effort she put into promotion. She admitted that she needed to have a full house regularly since she had no bar. Evanston was a dry town until 1972, although patrons brought alcohol to Fanny’s with no fear of a police raid. [Note wine glasses on the table in the illustration]

Fanny had started the restaurant in an industrial area in Evanston, Illinois, in 1946. She was a divorced mother of two boys facing the challenge of creating an upscale restaurant in a downscale neighborhood. She approached the local newspaper, the Evanston Review, asking if she could start a weekly column. She was told that restaurateurs did not have columns, so she bought a want ad instead. Almost accidentally, that provided a tremendous boost to her business.

Her Evanston Review advertisement was sent on to The New Yorker magazine by a professor at Northwestern University. The magazine included the entire, lengthy classified ad under the heading “Anticlimax Department (Fried Chicken and Violets Division).” It began with a quotation from John Milton (“‘They eat, they drink and in communion sweet, Quaff sweet immortality and joy”) and then told a story about visiting her uncle and aunt in Italy when she was 6. She spent time lying in the grass and smelling violets. Her aunt called her in to eat, and insisted that she do so even though she said she wasn’t hungry. Her uncle intervened and said she could go back and enjoy the violets. Next her classified ad launched into promoting dinner at her restaurant, suggesting that her “fine spaghetti” with its “rich meat and all butter sauce” would restore “SOMETHING that seemed lost.” Then it gave the restaurant’s hours on Sundays and the prices per various pieces of chicken, for example one chicken leg, 75c.

Marshall Field III, grandson of the department store’s founder, saw the New Yorker’s teasing putdown (did he recognize it as such?) and decided to give the restaurant a try. After his visit he introduced wealthy friends to it, including J. L. Kraft, Oscar Mayer, Richard Sears, and the presidents of Montgomery Ward and the First National Bank of Chicago. Fanny’s was well on its way to becoming a society restaurant. Although her first year in business had ended in the red, she was beginning to build a following.

Over the 40 years she ran the restaurant, Fanny invested in many, many advertisements, as well as producing 40 years worth of weekly promotional columns in the Evanston Review and the Chicago Tribune. Her paid advertisements appeared monthly for years in the Rotarian magazine. Despite being on the so-called wrong side of the tracks, Fanny’s location was not entirely a bad one. The Rotarian’s headquarters were only six blocks from the restaurant and it was close to Northwestern University and not so far from Ravinia’s summer music festivals. [above, an enlarged view of the restaurant, possibly in the 1960s]

She endlessly boosted the restaurant, repeating over and over that it had been honored by foreign governments and the Butter Institute of America, visited by famous celebrities, and written about in more than 165 newspapers and magazines. In her first column in the Tribune in 1955, she reiterated her triumphant claims: written up in 15 national magazines in the first two years; recommended by three of Europe’s finest restaurants in her fifth year, including the Tour d’Argent in Paris; and that she personally still prepared a garlic bread so fine that nobody had ever succeeded in copying it.

It’s likely that all her patrons and many others in the Chicago area, the country, maybe even the world knew Fanny’s saga: spending the first year serving industrial workers in the neighborhood, shoveling her own coal, and sleeping fewer than four hours a night. How she spent a full year each developing her salad dressing and her spaghetti sauce. And how she hired chef Bobby Jordan to fry chicken after he told her he had been “sent by the Lord.” And how she met her second husband, Ray Lazzar, while dining at the Pump Room where he was captain of the waitstaff.

Her success enabled her to live well and to become a local philanthropist. But she seemed to reveal her continuing insecurity after a student at Northwestern University gave the restaurant a poor review in the student newspaper in 1980. He wrote that Fanny’s was “overrated,” decorated to “look like it’s a rich man’s garage sale,” and that the spaghetti sauce was “just a tinge above Ragu,” while the salad dressing tasted “just above vinegar and oil with food coloring in it.” [above: a latter day match cover]

She responded by taking out a full-page ad in the student paper in which she reiterated her success, even going so far as to list in capital letters two columns with names of “GREATS” who had patronized her restaurant. She called her critic a “gross ignoramus” and concluded the long letter saying, “your bungling efforts at reporting a WORLD FAMOUS RESTAURANT WERE NOT ONLY WITHOUT TRUTH, BUT ODIOUS AND ABSURD.”

Two years later the school’s new restaurant columnist decided to give the restaurant another test. He was in agreement with the 1980 review and complained about soggy iceberg lettuce, greasy “orange-flavored” salad dressing and chicken that wasn’t “nearly as crisp as the Colonel’s.”

It’s hard to know if the restaurant had declined or if the student critics were poor judges of quality.

Ray Lazzar died in 1984, which was surely a blow, and the restaurant closed as of the end of July in 1987 at which time Fanny was 81 years old.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

February 9, 2025

Mobsters & racketeering

This post was inspired by a 1959 Life Magazine feature story on the Chicago underworld. The magazine created a fictitious café to show the goods and services that actual mobsters forcibly provided to restaurants. The illustration above indicates those areas of mob involvement commonly found in restaurants then – and probably now to some extent.

In the magazine, a brief description of some of the real life gangsters who had invaded restaurants was linked to the illustration, complete with headshots of them (not shown here).

Here is a summary of who furnished what:

1 Former Capone lieutenant operates in laundry (and produce) unions. (See my earlier post about gangsters in the restaurant laundry business.)

2 Hit man handles steam cleaning of beer tap coils.

3 Slot machine operator also gets a cut of juke box revenues.

4 Former Capone gunman is boss of bartenders.

5 & 8 Two gangsters push Fox Head beer and get a cut.

6 Another juke box boss also handles vending machine merchandise.

7 A third juke box boss runs 15 Teamster locals and handles delivery drivers.

9 Meat supplies are furnished by the syndicate nightclub controller.

10 Man who handles syndicate bookkeeping also sells glass-washing machines through a front.

11 Former Prohibition-era bootlegger handles liquor distribution.

12 Glassware and glass-washing boss handles machines that happen to break glassware, stimulating his business.

The movement of mobsters into these fields began at the end of Prohibition, when bootlegging became obsolete. The mob had infiltrated the Teamsters Union in Chicago, and used it to their own advantage, doing little if anything for the workers, who saw little benefit and in many cases did not even know they were members.

Strangely enough, Life seems to have left out mobsters in the trash removal business.

As the story explains, if the restaurant owner “balks, the syndicate can harass him by ordering pickets to scare off customers. If this fails, the mob, which controls waiters and bartender union locals, can call members out. Since the mobsters also control Teamster locals who deliver, they can put the owner out of business by cutting of his supply of beer or by stopping his garbage pick-up.”

The next step would be violence such as burning down the restaurant, dramatically so in the case of suburban Chicago’s Allgauer’s Fireside Restaurant in 1958, whose owner was being punished for testifying at a Senate hearing on organized crime. The “workers’ union” at Allgauer’s was under the control of a local underworld leader. The crime was never solved. I would say “curiously unsolved” except that was always the case.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

January 26, 2025

The short life of the Roboshef

In 1940 the restaurant trade magazine Restaurant Management ran a story about a new San Francisco restaurant called Roboshef where one presumably unskilled cook could turn out 120 meals an hour. The feat was accomplished by using an automatic cooker that rapidly cooked steaks, fish, potatoes, and biscuits in hot oil. (Opening 1939 announcement below.)

The counter-sized cooker (shown above), the Roboshef, was patented by Walter Scharsch, a chef who had previously run his own restaurant.

The Roboshef menu also included juices, salads, vegetables, soup, and desserts, all prepared conventionally. On the menu, a half chicken with French fries and hot rolls was priced at 60c.

In 1935, prior to opening the San Francisco location, Scharsch had spent some time demonstrating his invention in Portland OR. A story that ran in the local paper described him demonstrating the invention in a local auditorium (shown above). Local production of the machine, said the story, had begun that same day. It said the plan was to open the machine to distribution in Oregon, Washington, and California before going national. I could find no evidence that Roboshef restaurants ever opened in Washington or Oregon.

The invention had appeared first in Tiny’s Waffle Shop in San Francisco in early 1938. Next came the Roboshef restaurant described in Restaurant Management, with its grand opening in July of 1939. According to the trade magazine’s story, the business planned to dedicate the upper two floors of the Van Ness location to a commissary and an office.

And then what happened after 1939?

Nothing, nothing at all. The Restaurant Management story was the last trace of Roboshef.

Except for this, which appeared months before Restaurant Management’s 1940 story – on Nov. 26, 1939:

It does not list any restaurant equipment, but seems to be referring to what would have been in the upstairs office. However the restaurant must have closed then or not much later, because by April, 1940, two months before the Restaurant Management story, a Persian rug store had moved into the space formerly occupied by the restaurant.

So it seems that Restaurant Management had presented a new restaurant – that had already failed!

Why did the San Francisco Roboshef go out of business so quickly? I could not find any explanation. My guess is that the invention did not work properly. That might explain why Scharsch submitted a new design for a similar yet different “Food Cooking Unit” to the U.S. patent office in 1941.

The new version of the Roboshef was acquired by Cogrisch Products which christened it the “Cogrisch Chicken Fryer.” Two advertisements from 1941 exclaimed about using it to cook chicken, one at the Nip & Tuck Chicken Inn in San Diego and the other at Earl’s Tavern & Chicken Shack in Tulare CA. There may have been others. Both the Nip & Tuck and an unknown place in Tracy CA advertised their used Cogrisch fryers for sale in 1950.

Meanwhile, Walter Scharsch had gone on to work for a shipbuilding corporation and to invent a Butter Slicing and Dispensing Machine around 1945.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

January 13, 2025

Notable restaurant mottos

In 1925 a restaurant industry publication presented advice on crafting a slogan that would draw customers. The article advised against simply saying “Where to Dine” because that really didn’t signify anything special to the public. The author then gave better examples of slogans that were “clever and appropriate.”

As a negative example, the article might have pointed to Teck’s Quick Lunch in Kansas City [shown above]. This card showing “A Place to Eat” dates from 1907. I can’t help but wonder what about it was “So Different.”

Most of the article’s examples were not especially convincing as model slogans. For instance, the list included a Buffalo restaurant with the motto “Is Different.” The author also approved of the slogan of the Everest Lunch in Newark: “If You Eat the Best, Eat Here.” To me this cried out for a rewrite. Clearly, a better version would have been “If You Want the Best, Eat at Everest.”

The article inspired me to look at old postcards for examples of mottoes. Usually the restaurants that used them were not elegant and sophisticated, but rather everyday lunch counters, cafeterias, and roadside places.

Superlatives dominated. One of the most popular was the word “unique,” or even better (and more ridiculous), “most unique.” Those that merely claimed to be the most unique in a limited area, such as “Most Unique Terrace Between New York & Buffalo” (Camillos Spiedi Bar in Endicott NY), were surpassed by those that were the most unique in the entire country or beyond. For example, the Bank Café in San Pedro CA declared itself “The most unique café in the world.”

Sometimes I wondered if a slogan was a joke – for instance, when the Coffee Cup in Wolcott NY claimed it was “Known from Coast to Coast.”

Parking arrangements were a feature that often merited acclaim. Morrison’s Cafeteria in Ocala FL said for some unexplained reason that they had “America’s most unique parking lot.” Earlier Rhode Island’s Stork Club — the “Most Popular Night Club in New England” – asserted it was “The only club with bell hop parkers.”

Other very specific claims were made with regard to air. Chicago’s North American Restaurant of the 1920s was, it said, “The Best Ventilated Restaurant in Chicago.” Later, air conditioning came to be notable, but some places made a big deal of it, such as Hap Miller’s Truck Town Restaurant in York PA which was “Scientifically Air Conditioned,” while the Studio Club in Westchester NY was “Delightfully Air Conditioned.”

As was true of the 1925 examples, some sent an ambiguous message. The 1920s list included a Montana mining town eatery that claimed “Our Prices Encourage Thrift.” Although they surely meant that they had low prices, it could easily be taken to mean the opposite. Likewise, the motto of the Square Shooters Eating House in Wyoming, “An unusual restaurant for respectable people,” is puzzling. Unlikely place for them to patronize? Or, if the motto was meant to attract respectable people, what about it was so unusual that they would like it?

Other mysterious or odd slogans included:

– a Pennsylvania Dutch restaurant in PA that claimed “State Tested Water 100%.”

– Coleman’s Restaurant in North Carolina with “Chicken in the Easy Way.”

– Granger’s in Texas with its “Fish That’s Different.”

– Houston’s Weldon Cafeteria that announced it was “The South’s newest and most modern Two line Cafeteria.”

– Columbus Ohio’s Jai Lai Restaurant, with its slogan “In All the World . . . There’s Only One!” evidently referring to its kitchen costing half a million.

In a land of superlatives, my favorite was New York City’s Penguin Restaurant with the slogan “The Second Most Charming Restaurant in the Whole World.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2025