Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 9

October 30, 2022

Halloween soup

Although the food-page story in a New Orleans newspaper said that this photo showed a jack-o-lantern just carved by Chef Gunter Preuss for his children, I can’t help feeling a little bit spooked by it. Is it how he’s holding that knife, or his serious gaze?

Never mind, because the story was about the Harvest Cream Soup he makes out of the pumpkin’s insides. (See recipe below.)

At the time of this story, 1976, Gunter Preuss and his wife Evelyn were owner-operators of the Versailles Restaurant in New Orleans. Eight years later they acquired a part interest in Broussard’s, which they took over from 1993 to 2013.

The Versailles received a glowing review in Richard Collin’s “Underground Gourmet” column in 1978 — although it was definitely not a restaurant for the price-conscious diner. Collin declared it “spectacular,”and “about as fine a restaurant as one can imagine.” He singled out many dishes as “platonic,” meaning they could not be more perfect. Among them were Bouilabaisse Marseillaise, Rack of Lamb Persillades, Ris de Veau Grenobloise, and Pears Cardinal. Chef Preuss was also featured on the show Great Chefs of New Orleans.

The recipe for pumpkin soup does not give amounts for every ingredient. It calls for a pumpkin’s interior, seeds removed, to be cubed and washed. Then sauté the cubes with onions and celery until glazed. Add flour and a half quart of chicken stock. Simmer the mixture over medium heat for 45 to 60 minutes, seasoning with salt, white pepper, powdered ginger, and white wine. Then strain the soup and add three eggs yolks and a cup of light cream. Simmer on low flame for five minutes, then pour into cups and serve with a whipped cream topping and a touch of ginger. Serves six.

Enjoy Halloween!

October 23, 2022

Restaurant-ing with John Margolies

The multi-talented John Margolies spent nearly 40 years on the road taking tens of thousands of photographs of roadside businesses. He focused particularly on those with bright paint, unusual signs, or odd shapes. Often the buildings were amateurish constructions, sometimes abandoned and forlorn looking [above, Orange Julep, Plattsburgh NY, 1978].

Restaurants and ice cream stands were frequently his subjects, as were motels and gas stations. The photos were notable for the absence of people, which tended to give them a strangely monumental appearance as well as a degree of pathos. The sky was always blue, often cloudless, even if he had to wait for days to take the shot. It is clear that his involvement with these subjects was highly personal. [Daisy Queen, Greenville SC]

He produced at least a dozen books using his photographs and ephemera from his and other collections. Among them were The End of the Road: Vanishing Highway Architecture in America (1981), Pump and Circumstance: Glory Days of the Gas Station (1994), and Home Away from Home: Motels in America (1995). An elegiac tone concerning the buildings and businesses made obsolete by interstate highways, fast-food chains, and big box stores suffused his project.

Rejecting the distinction between good and bad taste, he was determined to put popular culture on a par with elite high culture. For example, he admired the flamboyant architecture of San Luis Obisbo’s Madonna Inn, designed by its owners who were untrained as architects. His photographic choices reflect his dedication to this mission.

How fortunate that nearly 12,000 color slides of Margolies’ work have been acquired by the Library of Congress and can be viewed online.

I have selected a few of the hundreds of restaurants whose images he captured. For the most part, these restaurants were not the sort to do much advertising or to be reviewed in newspapers, so they are difficult to research. For example, little is recorded about the barrel-shaped eateries he photographed, such as The Beef Burger in Amarillo TX. I suspect it may have once served as an A&W rootbeer stand.

The Fish Inn of Coeur d’Alene ID, on the other hand, often cropped up in local newspapers. It was designed by its husband-and-wife owners in the mid 1930s. It changed hands often and probably stood empty for a time, yet amazingly enough has survived into the present, primarily as a roadhouse with live bands.

A Spokane WA newspaper columnist in 1936 described it as “a grotesque structure, made in the shape of the fish, with its shingled sides representing scales and the huge mouth the main entrance.” That attitude would change. By the time Margolies photographed it in 1987, appreciation for what became known as “roadside America” had spread across the land and the Fish Inn had been noted as one of its gems. There were other odd structures in the greater Spokane area such as a creamery’s 38-ft tall milk bottles, the Miner’s Hat in Kellogg ID, a giant Paul Bunyan, a tavern in the form of a prairie schooner, and a number of pseudo-windmills.

After standing empty for several years The Boat Restaurant in Vernon NY was reopened in 2008, but possibly later closed and demolished. According to a brief note on the Oneida County History Center site, a longtime former owner dated it to 1923. Margolies photographed it in 1988, by which time it had lost a few of its original features. Why the restaurant was built as a boat is unclear other than to attract the attention of passersby. Many eating places have adopted the shape of boats over the years.

As a storefront restaurant built in an alleyway in the 1930s or 1940s, the 12-foot-wide Town Talk Diner was a “greasy spoon” notable for its cheap burgers, cream pie, and giant modernistic sign. Because of its front it is not strictly a piece of vernacular architecture, but it no doubt captured Margolies’ interest in 1984 because of its sign. Located on E. Lake Street in Minneapolis, it — along with many other businesses in the vicinity — was burned to the ground during protests against the killing of George Floyd in 2020.

In 2017 it had been taken over by new owners who renamed it the Town Talk Diner & Gastropub. Noticing that most of their guests came from out of town, they were puzzled about the lack of local customers. They discovered through social media that many thought it was still a diner, mainly because of the sign. How odd that what attracted Margolies kept customers away.

Powers Hamburgers, built before WWII, has survived fast-food competitors and thrives to this day in Fort Wayne IN. It even has a Facebook page. Like the Town Talk Diner, it seems quite different than vernacular buildings such as the Fish Inn and The Boat. Rather than whimsy, Powers and the Town Talk both display the influence of European moderne design as interpreted by professional designers. Powers Hamburgers reminds me of the architect-designed units of the White Tower chain in the 1930s with their white porcelain paneled exteriors.

In his later tours Margolies photographed fast food chain units, including a few McDonald’s, Bennigan’s, Papa John’s, and a Del Taco. Buildings by corporate chains with staff architects do not seem to have much in common with his earlier subjects, especially considering that their rise was responsible for the failure of so many “mom and pop” businesses. I’m still puzzling over that.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

October 9, 2022

True confessions

Through the years a number of writers have described deceptive practices and foul scenes in restaurant kitchens where they have worked. Probably the best known authors are George Orwell (Down and Out in London and Paris, 1933) and Anthony Bourdain (Kitchen Confidential, 2000).

In those books, and in periodicals, I’ve read many reports of bad restaurant food, along with dishes misrepresented on menus. But I’m still a bit stunned after reading Restaurant Reality: A Manager’s Guide by Michael M. Lefever (1989). One of the biggest surprises is that he reveals his own willing involvement in kitchen tricks and horrors inflicted on guests — even in restaurants he and his wife owned and operated.

The book has a puzzling disclaimer on the copyright page: “This book is a composite of the author’s own experiences. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or locales is purely coincidental.” But, whether absolutely factual or not, and despite being aimed at college students interested in restaurant management, the book seems to sanction questionable activities.

In his preface to Restaurant Reality the author makes several statements that seem to undermine the disclaimer somewhat. He says that he tried to present “an authentic overview” that was “a real eye-opener for anyone who has ever eaten in a restaurant.” He adds that while the content may be shocking, “that’s how things really are.”

Starting at age 14, Lefever had at least a 23-year career in a number of restaurant roles, including dishwasher, server, cook, and bartender for an Italian restaurant, followed by unit manager and district manager for a fast-food chain, and regional manager for a dinner-house chain. Plus, in between the chains, he and his wife were owner-operators of three independent restaurants. Following his restaurant career, he held academic positions both as Associate Dean of the Conrad Hilton College of Hotel and Restaurant Management at the University of Houston and as head of the Department of Hotel, Restaurant and Travel Administration at UMass Amherst.

Although no names of individuals, places, or restaurants are given in the book, I have discovered that the third restaurant the Lefevers owned briefly was The Balcony in Folsom, CA. According to a 1983 story in the town’s paper, their two previous restaurants were in Bend OR and Salt Lake City, probably in that order.

How things really were

At age 16 Lefever became head cook at an Italian restaurant. It was before microwave ovens were common so hot water was used for parboiling and defrosting items such as lobster tails. The same water might be used for multiple items, such as pasta, chicken, and fish, as well as frozen steaks before they went on the broiler. He remarks, “This may be of some interest to readers who are strict vegetarians.”

No matter what the customer ordered at the Italian restaurant, all steaks were delivered to guests rare and cooked further only if they complained. If the customer insisted on a well-done steak the kitchen took revenge by putting it in a deep-fat fryer, followed by treatment with a blowtorch which caused it to burst into flames. Just before it burned to a crisp they would throw it on the floor and smother it in salt, then shake off the salt, put it on a platter and brush it lavishly with butter. He claims – and maybe it was true – that customers loved these steaks and some started asking for theirs charred.

As a fast-food unit manager, he oversaw (or witnessed? or heard about?) some truly disgusting practices. For instance, afternoon employees hired mainly to clean toilets and dispose of trash often did some off-hour cooking as well — but they weren’t always terribly sanitary. If no fresh lettuce was available, he writes, “the afternoon employee might fish out of the garbage can some discarded outer leaves.” They were oversized with tough spines, so the worker would “simply place his palm on the assembled sandwich and smash it downward.” When condiments squished out, he would “take a dirty cleaning rag” and wipe off the bun.

Since Lefever’s monthly bonus was based on keeping costs down, he recycled sandwiches that had officially expired as often as he could, even though this subverted the chain’s system. Eventually they began to look inedible. Then the workers would replace limp lettuce, spray the dry bun with water, and make other repairs. If that didn’t work they would disassemble the sandwiches and salvage the valuable parts for remakes during the off-hours, and so much the better if the customers were nighttime drive-thrus who had spent their evenings in a bar.

At the Lefevers’ own restaurant, The Balcony, servers were instructed to tell customers that all dishes — Veal Piccata, Beef Wellington, and so on — were prepared on site though they actually came from a supplier of frozen entrees. The cooks were highschool students who defrosted them in a microwave while doing their homework.

He declares that customers who found eggshells in their omelets should have been grateful since this meant the restaurant used fresh eggs rather than processed omelet mixes. But it could also mean that they came from the bottom of containers they used to store hundreds of cracked eggs in water. And, he reveals, “The bottom also collected the heavier eggs, which result when hens are sick, given a strange diet, or frightened.” Customers requesting decaffeinated coffee didn’t necessarily get it, since servers randomly grabbed the handiest pot, switching the red or green plastic bands that indicated type of coffee.

In discussing food spilled on the floor, he writes, “I have served . . . entrees spilled and then salvaged such as lasagne, beef stew, chili, pasta, and scrambled eggs. Steaks and chops are no problem at all. Simply put them back on the grill or in the pan to freshen them, after washing them under the faucet.” But he advises cooks to inspect the entree “looking for hairs and foreign pieces of food that do not complement the dish.”

Lately I’ve found myself eager to eat at home.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

September 25, 2022

Basic fare: pancakes

After a start in the 1950s, pancake houses made it big in the following decade.

Of course pancakes were not new to eating places. Far from it. They had long been a staple of short order restaurants, known variously as flapjacks, hoecakes, hot cakes, griddle cakes, flannel cakes, batter cakes, butter cakes, and just plain cakes. The mighty Childs chain had built its business by transfixing pedestrians with women flipping pancakes in its windows.

Cheap yet filling, it’s hardly surprising that pancakes grew in popularity during the 1930s Depression. The Childs Corporation reported in 1931 that pancakes with butter and syrup ranked as “the most typical American dish.” Pancakes were once again in the spotlight in the film Imitation of Life (1934) in which a white woman’s Black cook runs Aunt Delilah’s Pancake Shop which makes a hit on the Atlantic City boardwalk. The 1930s was also the decade in which The Pancake House opened in Portland OR – a restaurant which James Beard playfully nominated in the 1950s as one of the 10 best in America.

But what was new in the 1960s, with the spread of economic prosperity through (white) America, was the popularity of the “family restaurant.” Children, who had earlier been a minor element in eating out, became a new factor in restaurant success. Now included in dining plans, they often ascended to the role of lobbyist and de facto decision maker. And, while Mom might frown on high-calorie menus and Dad might wish for steak, the kids loved pancakes.

Pancake restaurants of the 1960s welcomed children with bright primary colors, cartoonish figures on menus and walls, and at least in one case with a rather alarming-looking costumed clown. If a child had not fully satisfied their sweet tooth with pancakes, they could raid the “old-time” candy barrels at Florida’s Kissin’ Cousins Pancake Inns. Meanwhile, an adjoining cocktail lounge beckoned parents with beer and bourbon.

What else was new about pancake restaurants? They were part of the advent of eating places focused on single foods, such as hamburgers or pizza. Like pizza, pancakes held special charm for restaurant owners because their ingredients were cheap and no skilled cooks were needed. Plus, they weren’t just for breakfast — customers were ready to order them all day and through the night. The trade journal American Restaurant mused in 1960, “Who ever dreamed that the lowly pancake would build a fortune . . .?”

Restaurant consultant George Wenzel asserted that pancake houses proved “that any one item, prepared with great care, and basically popular, can lead to fortunes especially if the menu price is reasonably low.” While regular service restaurants had food costs up to 48%, he figured they were only 35% in specialty restaurants such as pancake houses.

Chains built around pancakes spread rapidly. By 1961 the International House of Pancakes had opened 25 units in just three years, and was poised to expand into the Northeast. Uncle John’s Pancake Houses, begun in 1956, were doing business with 60 units in more than 20 states. Each of these chains may have been inspired by Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House that opened in Disneyland in 1955.

Despite the development of dozens and dozens of pancake varieties and their high profit margins, pancake restaurants gradually broadened their menus. The trade magazine Cooking for Profit noted in 1964 that pancake restaurants had found it necessary to put steak on the menu. The growing menus meant that the pancake restaurant boom would soon give way to a more general sort of family restaurant in the 1970s. Like pancake restaurants, full-service family restaurant chains such as Denny’s and Country Kitchen were also expanding.

Eating in restaurants continued to be popular with families in the 1970s. Reporting on a Gallup survey in 1975, Food Service Magazine observed that more working mothers, increased family income, and smaller families suggested “a more profitable family market than ever before.” The survey also found that preferences included table service restaurants that welcomed children, had moderate prices – typically $1.00 to $1.99 per person for breakfast — and a menu with a wide range of selections.

A 1978 New York Times story titled “Family Restaurant Booming” noted that dining out is extremely sensitive to economic conditions, a situation that is likely to be especially true for family dining.

So the current economy should favor patronage at IHOP, the reigning pancake kingdom.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

September 11, 2022

Black waiters in white restaurants

In the 19th century Black waiters staffed most Northern restaurants and hotel dining rooms, particularly as hotels grew larger and better appointed beginning in the 1840s. Earlier, Black waiters in the North were mostly employed in private residences or for catered events.

Before the Civil War, the hotels were run on the American plan where meals were included with lodging and served family style. Mealtime was often a mad scramble, putting waiters under great pressure to bring out the dishes. They were often ridiculed, or seen as having no other virtue than being imposing-looking in uniforms.

After the Civil War, when the tipping custom spread, they were suspected of being interested solely in tips. Nevertheless, jobs as waiters were sought after and those who held them were highly respected in Black communities. Headwaiters, occupying a role similar to that of maitre d’, enjoyed the highest status.

A number of Black waiters rose in their profession and took the role of advisor and trainer of their fellow servers. An early example was Tunis Campbell who published The Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeepers’ Guide in 1848. He presented the headwaiter’s role as similar to an officer whose troops need a lot of drilling lest they became undisciplined and boisterous when facing a mob of impatient guests. His advice was put into practice, judging from an English traveler’s description of a remarkably choreographed scene in the 1850s. He reported that, “At a given signal, each [waiter] reaches over his arm and takes hold of a dish . . . at another signal, they all at the same moment lift the cover, all as if flying off at one whoop, and with as great exactness as soldiers expected to ‘shoulder arms.’”

Some patrons preferred Black servers to white ones, and it was said that the better restaurants and dining rooms of the post Civil War period preferred them to whites, particularly the Irish. But praise was often blended with condescension. A prominent Chicago hotelier noted that Black waiters were the “best.” But he added, “They are waiters by nature, and are peculiarly adapted to servitude.” Another admirer of Black waiters commented in a similar way: “White waiters always have an idea that they are doing a man a great favor if they serve him promptly and are polite and respectful. Colored waiters know their place and keep it, give themselves no airs, and take no liberties.”

Never did it seem to occur to white commenters that the best Black waiters had actually chosen to dedicate themselves to their profession and constantly improve their skills. Nor that they were performing a role rather than conforming to their nature.

Unsurprisingly, given the lack of a wide range of job opportunities, many Black men were known for their long tenure as waiters. Still, it is interesting that a Chicago restaurateur noted with surprise in 1899 how many Black waiters “find their way to the variety stage.” Perhaps they had been drilled in the Campbell method. [Blaney Quartette poster, 1898]

The position of headwaiter was especially coveted, particularly if a Black man was tall and impressive looking in a uniform, often a tuxedo in the 20th century. However, although some remained, by then the position of Black headwaiter was being replaced by restaurant owners and hostesses taking over the job of greeting and seating guests.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries a white backlash against Black Americans generally reduced work opportunities even further, threatening Black predominance as waiters. Immigrant men arriving in this country proved willing to accept jobs as waiters. However, there was a notable reason to favor Black men, one that hindered them at the same time. As a Black waiter explained in 1903, for Black men being a waiter was “usually the zenith of his industrial possibilities” and because of this there was strong competition among them for these positions. This allowed hotels and restaurants to pay them less than white waiters.

By the 20th century, white women also took jobs serving in restaurants, often replacing Black men. Actually, though, the Fred Harvey organization may have pioneered the shift from Black men to white women. In 1883 the men – considered troublesome – were replaced at one of the eating houses on the Santa Fe Railroad line, launching the phenomenon of the “Harvey girls.” Unlike white women, Black women were not often found waiting in white restaurants, but were more likely to be working in the kitchens. When they did occupy waitress roles, white patrons seemed to enjoy seeing them dressed in .

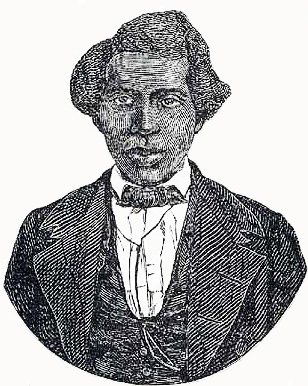

Black waiters organized mutual aid societies and employment bureaus as early as the 1820s, but many were skeptical of labor unions. When strikes failed, their distrust was intensified and they felt they had been betrayed by the white unions, particularly after losing their jobs and being replaced by white men and women. A failed strike at a lunchroom chain in Chicago in 1903 was long remembered with bitterness. Leading Black waiters supported advancement for Black waiters, but not of joining unions. John B. Goins wrote in his book (The American Waiter, 1908) that “unions will never be of any benefit to a colored waiter.” In an even stronger vein, he advised, “Keep out of strikes. If you are asked to join in a strike for better wages refuse point blank. And I would advise you to offer to quit; but first explain why you do so, stating your reason for quitting is to keep out of strikes.” His ally, Forrest Cozart (author of The Waiters’ Manual), was another strong proponent of improvement, urging Black waiters in American plan hotels to learn to read and write because such hotels were disappearing. [Forrest Cozart shown below]

Though there were still an appreciable number of Black waiters through the 1920s, competition with whites increased during the Depression of the 1930s. Then, even native-born whites who had long objected to taking service jobs began to compete successfully, significantly reducing the number of Black waiters.

After World War II, when the economy had improved, dining out for pleasure increased substantially in this country. Black waiters discovered that they were often shut out of waiting jobs in fine restaurants where there was a chance to make good tips. Possibly, though, Black waiters were favored in Southern restaurants such as the elegant Justine’s in Memphis, which hired a strictly Black waitstaff from its beginnings in 1948 until closing in 1995. The restaurant made much of the fact that many of its waiters stayed on the job for many years, yet there were signs of dissatisfaction on their part such as walkouts and complaints about low wages. Many had full-time day jobs.

A 1985 case study found that, unlike immigrants, Black men were not eager to be waiters in low-priced restaurants and that they were not often hired in the better eating places. How much this was due to racist attitudes on the part of managers and/or patrons was not clear. But the study noted that even “when the supply of European waiters fell during the sixties, New York City’s full-service sector did not hire blacks into these relatively high paying jobs, but used artists and actors instead.”

By 1970 Black servers, either male or female, made up only 16% of all waitstaff according to research by Dorothy Sue Cobble (Dishing It Out, 1991).

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

August 28, 2022

Catering to airlines

After the early years of serving cold box lunches, U.S. airlines tried to improve their in-flight food service through alliances with restaurants and restaurant chefs. As early as the 1930s, the decade in which transcontinental flights began, hot meals were becoming common. In 1939 George Rector, formerly of the swank and swinging Rector’s of pre-prohibition Broadway in New York City, advised Braniff Airways on their menus. He gave his blessing for a Thanksgiving menu that year that included roast turkey with oyster sauce and chestnut dressing, pickled watermelon rind, and other select dishes.

It’s fair to ask why airlines switched from cold box lunches, given how difficult and expensive it was to provide full-scale hot meals. A large part of the answer is that in the beginning they wanted to distinguish themselves in comparison with train travel. Over time, though, planes would become bigger and faster, offering cheaper fares and attracting many more passengers. Through all of this, meals would go from an attraction to a target for cost reduction.

It’s hard to know exactly what Rector’s role entailed. It may have been devising menus and training chefs rather than getting his hands dirty. Decades later that was probably equally true of another well-known chef, Wolfgang Puck of Spago in Los Angeles. In 1983 he advised luxury Regent Air Corp. on suitably impressive meals for its flights between LA and Newark. After being delivered to the airport via Regent’s limousine, passengers were treated to Beluga caviar, smoked salmon, and lobster fresh from Maine, washed down with fine wines. Within three years the airline had racked up $36 million in debt and was sold.

United Airlines was one of the few airlines that maintained their own flight kitchens. Starting in 1947 they were headed by Swiss chefs. Trained in European kitchens, they came to United with experience in major hotels and restaurants in the capital cities of Europe and America. Nonetheless United’s menus, whether in English or Franglais, were less than thrilling, especially when the various courses were all grouped together on a tray as depicted on this late 1960s postcard. Even though I’ve seen many United menus, I remain stumped about the ingredients in the “salad” that look remarkably like asparagus spears reposing on a bed of orange gelatin (though, to be fair, I’ve never seen gelatin on a United menu).

There were no Swiss chefs at the D.C. area’s Hot Shoppes drive-ins in 1937 when that company began to supply Eastern and Capital airlines with in-flight meals. Eventually the Hot Shoppes would become the Marriott Corp., a major airline caterer that became one of the largest, as did another that evolved from a restaurant chain, Dobbs House.

Meals in the 1950s may have been somewhat ho-hum (despite the fact that almost all flights were still first class only), but alcoholic beverages brightened the trip for some passengers. Despite the failed efforts of Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who introduced legislation in 1957 to outlaw the sale of alcohol on airplanes citing both safety and moral issues, nine domestic airlines began serving it in the 1950s, and the number grew from there. [Above, Delta, 1959]

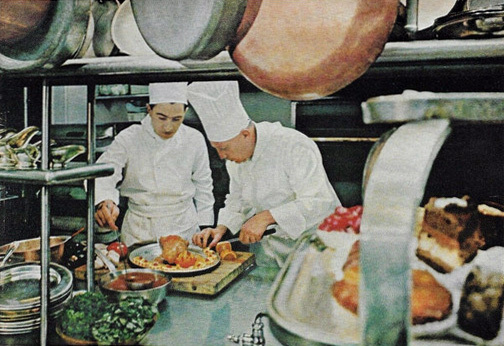

Two free drinks became an attraction offered by a number of airlines as they ramped up their meals. Competition in cuisine became intense among the major carriers in the 1960s, in some cases involving the participation of fine, or at least famous, restaurants. This was perhaps inspired by Pan Am who recruited Maxim’s to supply meals for flights departing from Paris. Soon airlines in the U.S. began to conjure intriguing flight names such as Famous Restaurant Flights, Captain’s Table, and Royal Dining Service. American Airlines enlisted “21″ to supply flights leaving NYC, while Eastern – once catered by the Y.M.C.A. – signed up the elite Voisin for first-class flights from New York and the Pump Room for those from Chicago. Eastern discarded its humdrum serving pieces [at top of page] of old for Rosenthal china and stylish silverware [shown below]. As a commentator said in 1967, “ Practically every airline worthy of the name also calls itself a flying five-star restaurant.” [above, Voisin chefs preparing food for Eastern Airlines, 1965]

The peak of competition in food probably occurred in the early 1970s, when airlines offered champagne breakfasts, a variety of hors d’oeuvres, lobster plus steak dinners, and prime rib sliced on a rolling cart for each guest — ditto for displays of salad tossing. Passengers could request special meals designed to suit taste, health, or cultural/religious requirements.

Through all of this, though, there were always complaints about food. Almost everyone agreed that warmed-up meals could never match good home cooking or fine restaurant fare. And, of course, there were those who preferred to make their own arrangements and have the cost of meals subtracted from the cost of their ticket.

They got their wish in 1978 with the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act. Airlines were freed to compete in terms of fares and routes. New airlines were created. Some old ones grew mightier while others, such as Braniff and Eastern, disappeared in the 1980s recession. “Frills” were eliminated. Snack packs came into being, making the sandwich and apple of the 1930s seem almost generous. In the 1990s United began offering McDonald’s meals for children.

While hot meals did not completely disappear, they tended to be limited to first class passengers whose proportionate numbers had shrunk drastically since the 1950s. Today, meals by foreign carriers get the highest ratings.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

August 14, 2022

What were they thinking?

I have often been struck by how many postcards fail to present restaurants at their best. Most of those I’ve chosen for this post are from popular restaurants, some of which stayed in business for a very long time and were well loved.

But the whole idea behind postcards was to extend the appeal of a restaurant beyond its regular patrons, to those who perhaps never even heard of it. What would strangers think about the places associated with these self-presentations?

Why show an exterior like this?

I don’t know what explains the sad appearance of the Olympia Oyster House. It was a popular spot that had been around for decades, but the front of the building in 1971, with its high-school-gym style and blanked out window, does not seem attractive even to the people in the photo. It seems they can’t quite bring themselves to enter.

Apparently the Hilltop Restaurant, shown here in 1960, was listed for sale for an extended period of time. Years and years — all the while doing business. Nothing like a patch of weeds to set off a place.

The names!

Please, no more Squat-N-Gobbles! Such a strange name for a white-tablecloth restaurant advertising “Dinner by Candlelight.”

And yet, having no name at all doesn’t work well either.

Identity crisis

As names go, Mammy’s Kitchen is offensive, and, in the case of this 1970s Myrtle Beach restaurant, does not seem to have anything to do with either the food or the strange atomic symbol hovering overhead. Its cuisine is likewise heterogeneous, covering the usual steaks and chicken, but also offering “Italian Kitchen and KOSHER SANDWICHES.” New management took over in the mid-1980s but the objectionable name from an earlier age was still in use as late as 2019.

The Wolf’s Den in Knox, Pennsylvania, opened in 1972 in a very old barn that had been decorated with plows, saddles, old rifles and such. The section called the Hay Mow is shown on this card. Something about the dusty appearance of dried out straw and the chains and hooks does not convey an enjoyable dining experience. According to a 1977 review, the restaurant was expensive and served “standard American fare” such as escargot and French onion soup. I’m confused.

Do these look delicious?

German pancakes have been a favorite at Pandl’s Inn in Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin, for decades. The trouble is they don’t photograph at all well. It is also a mystery to me why anyone would accompany a large pancake with a basket of bread and rolls.

A similar problem afflicts the specialty ice cream pie at Tripp’s Restaurant in Bar Harbor, Maine.

The postcard was almost certainly created to celebrate the opening of the Sirloin Room at Dallas’ Town and Country Restaurant in 1951. Of course steaks are brown, plus this one seems to be resting in a pool of its own juices. I can see that some touch of color was needed, but maybe this parsley is a bit much.

Threatening interiors

Probably when you’re actually in King Arthur’s Court, a room at the Tower Steak House in Mountainside, New Jersey, the deadly implements wielded by the suits of armor recede into the distance and the blood red carpeting is barely noticeable. But in this shot they loom disturbingly.

No, the lion is not actually holding a gun, but she is showing her teeth in a menacing way. Likewise those antelope horns look sharp at the Kenya Club in Palm Beach, Florida.

This light fixture? sculpture? installation? might just be the ugliest I’ve ever seen. Let’s hope that it was well connected to the ceiling of the William Tell Restaurant in Chicago. Then there are the inset wall displays, and . . .

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

July 31, 2022

Dining underground on Long Island

A couple of weeks ago when I wrote about the various editions of the Underground Gourmet, I omitted Long Island and Honolulu because I couldn’t find those books. But then a reader generously sent me a copy of the Long Island Underground Gourmet.

If you were looking for inexpensive restaurants with good food on Long Island in 1973, you might have been disappointed by the Underground Gourmet. It has me puzzled. Why were so many restaurants rated as expensive and even very expensive included in the book? Was it because of the opening sentence in the Foreword which said , “People still persist in saying there are no good restaurants on The Island.”

That sentence and others that say Long Island “has long been in the shadow of New York” and is “unjustly ignored” make me think that demonstrating the existence of fine restaurants took precedence over advising readers where they could find good food at bargain prices. The author’s belief that the Island’s restaurants were not well regarded was reflected in a 1972 restaurant review in New York magazine with a pull-quote referring to the Hamptons area as “a culinary desert.”

But, indeed, just how wonderful were many of Long Island’s restaurants that were rated “expensive” ($10 to $14) or “very expensive” (“Bring your checkbook”)? Barbara Rader made some ambiguous assessments of some of them, not saying they were bad, but planting little seeds of doubt. For example, she commented that the “very expensive” Greenbriar in Great Neck was beautifully decorated but, “I wish I could be as enthusiastic about the food as the decor.” Of the expensive Sans Souci, in Sea Cliff, she wrote, “the food is fairly good.” Similarly, expensive-to-very-expensive Hadaway House in Stony Brook had “some fairly good dishes.” The venerable Beau Sejour (“expensive to very expensive”) in Bethpage offered “good-to-excellent food” but sounded as though it was on the point of collapse, with “paint and wallpaper . . . showing their years, the chairs . . . a bit rickety and the electric wires draped across the paintings on the dining porch . . .” It closed a short time later.

The book leaves the impression that if Rader had limited her survey to “finds” comparable to those in other Underground Gourmet editions it would have made for a very slim volume. About 38 of the 300+ eating places covered in the book are given “mini reviews” of one short paragraph. They are mainly seafood stands, pizza joints, luncheonettes, and diners. No price range is given for them, but presumably they would fall in the category of “low cost” (95 cents for a meal) or “inexpensive” (under $3). I wonder if some of these would have qualified as finds but not a lot is said about the quality of their food.

There is not a great deal of cultural variety represented in the book, but what little exists is captured in a few of the mini reviews. Examples include a soul food place (Reid’s Bar-B-Que in Copaigue); a Puerto Rican restaurant (La Lechonera in Brentwood); and Pepe’s Taco in Smithtown.

Perhaps to make up for the small number of bargain places with good food, the book concludes with 13 pages of chain and fast food restaurants. The section includes some local/regional chains such as Wetson’s, serving “Big Ws” at 16 Island locations. Her assessment of it is “Strictly a drive-in, mobbed with families with kids, or with young couples with poorly developed palates.” Of the Big W she says, “Stick with the plain hamburgers.”

Other restaurants that I would think could be considered finds fall in the inexpensive to moderate ranges ($3 to $7 for a meal). They include Linck’s Log Cabin in Centerport (“A food fantasy for families; good food”); The Elbow Room in Jamesport (“plain but excellent food”), Wyland’s Country Kitchen in Cold Spring Harbor (“good home cooking”), and Gil Clark’s in Bay Shore (“one of the best known seafood houses on The Island” with “better-than-average food”).

Rader as well as the NY Times’ critic Craig Claiborne were in agreement that the “expensive to very expensive” Capriccio in Jericho was, as Claiborne put it, “probably the finest restaurant on Long Island,” one that could easily compete with the city’s best. However, on the whole the Long Island UG makes me think that the Island still had one foot in the era when many customers prized decor, atmosphere, and deferential service over cuisine, and were not interested in adventurous dining.

The contrast between Long Island in 1973 and San Francisco in 1969, as painted in the two books, is quite striking.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

July 17, 2022

My blogging anniversary

It’s kind of scary to realize that it’s the 14th anniversary of my blog.

At the start – July 17, 2008 – I thought it would be so easy. I thought I’d build my posts around my collection of restaurant memorabilia such as the match books above. I imagined it would take me about half an hour to write each post, and in fact the first one didn’t take much longer than that. That is no longer true.

Since then I’ve revised that initial post — Joel’s bohemian restaurant – because I came to realize it was much too sketchy. I’m thinking of revising it a second time.

My blog posts have grown longer, though I try to keep them relatively brief, and I have extended my topics way beyond the possibilities of my ephemera collection. Now my process is reversed and I’m always on the lookout for elusive images that are relevant to subjects I want to investigate.

When I began, WordPress was a folksy kind of blog host. I always got a quick answer to queries about how to do things, and they were signed with first names. The company made relatively little effort to sell additional services or to get bloggers to add advertising to their site.

They did, however, place advertising on sites without asking. The day I discovered that WordPress had inserted a weight loss advertisement into one of my posts, I shouted NO! Then I immediately signed up for “No Advertising” even though I had to pay an annual fee – and still do.

Now, after publishing 496 posts and pages, I remain glad that I didn’t “monetize” my blog.

Another change in WordPress (for the better in this case) was the ability to link posts easily to other internet sites such as Facebook, Twitter, etc. – and for readers to click “Like.” My early posts have no Likes, not because I had no readers but because there was no Like button then.

I am thankful for my readers and followers. I’m happy that they are interested in what I write about and that they bring a lot of knowledge about restaurants with them. Along with on-site comments, I get an equal number of emails from readers, some looking for additional information and others who kindly go out of their way to send compliments.

Another nice aspect of producing my blog are the occasional invitations to give talks and interviews.

Now, when I go back and look at my old posts I always see something that could be improved – where I should add a link or illustration (see part of my image file above), reword an awkward sentence, clarify a murky point, or insert something I’ve since discovered. Usually I try not to obsess over these shortcomings and end up moving on.

Although I often profile individual restaurants, frequent readers probably realize that my greatest interests are how the custom of eating out grew, how the various types of eating places developed, the types of food and ways of cooking that are highly associated with restaurants, and how restaurants reflect American culture.

A few of my favorites posts are linked here, some of them early ones that are deserving of more attention.

Let’s do brunch – or not?

Swingin’ at Maxwell’s Plum

You want cheese with that?

Eat and run, please!

Basic fare: club sandwiches

Back in 2008, a friend asked if I feared that I would soon run out of topics. That still makes me smile. I haven’t even come close.

Thanks for reading!

July 3, 2022

Underground dining

In the 1960s, with the rumble of social change came a flood of interest in low-priced eating places with character and good food. In this spirit, New Yorkers Milton Glaser and Jerome Snyder began a newspaper and magazine column titled The Underground Gourmet, followed by a guide book in 1966 with the same name.

Their book led to a series. It’s been a little difficult to nail down how many different UGs there were, but here is my list, with initial publication dates: New York (1966), San Francisco (1969), Los Angeles (1970), Washington D.C. (1970), New Orleans (1971), Boston (1972), Honolulu (1972), and the noncity Long Island (1973).

Several factors probably contributed to the new mood regarding restaurants. The economy was bad and the public was looking for bargains. Youth culture was blossoming as the baby boomers grew older, many becoming college students. And increased travel abroad was widening the public’s interest in unfamiliar foods and ways of cooking.

The public’s attraction to low-priced independent restaurants could also be seen as a reaction against the growth of fast food chains taking place, the greater use of frozen food in restaurants, and a rebellion against the blandness of much American food.

What was considered a low price for a meal during these years? The first New York edition specified in 1966, “Great meals . . . for less than $2 and as little as 50¢.” But the third edition (1977) explained that “unending inflation . . . has changed our perception of an inexpensive meal from one that cost $2.00 to one that costs $5.00 or $6.00.” For the New Orleans’ second edition in 1973, author Richard Collin promised meals “for less than $3.75 and as little as 50c.” This was still a lower price than featured by the others, which ran from $1.00 to $3.75 in San Francisco in 1969; $1.00 to $4.00 in D.C. in 1970; and “under $4.00″ in Boston in 1972. Dining in Honolulu remained a bargain, with the 1972 UG promising meals as inexpensive as in the first New York edition (50¢ to $2).

Low price was not really what set the best of the recommended restaurants apart from others. Rather it was the quality of the food for the price. Although Mr. Steak in 1970 offered its most expensive meal – Steak & Lobster with salad, toast and potatoes – for $3.99, it didn’t make the cut, though strangely enough a few other chain restaurants did win recommendations including a McDonald’s in D.C. and a Burger King in New Orleans.

What were some of the most remarkable finds in these books? Richard Collin [above cartoon] discovered a number of dishes that he gave his highest praise, naming them “platonic dishes,” as perfect as that dish could possibly be. His New Orleans list of platonic dishes included Oysters Bienville and Fried Chicken at Chez Helene’s soul food restaurant — which he rated one of the city’s finest restaurants; Creole Gumbo at Dooky Chase; and Fried Potato Poor Boys at the dirt-cheap Martin’s Poor Boy.

The number of restaurants that met the criteria varied from city to city. Boston and D.C. are notably slim books. New York is the fattest volume. San Francisco and New Orleans have about 2/3 the heft of New York. However, with his shorter entries, Richard Collin packed over 250 restaurants into the 1973 revised New Orleans edition, rating everywhere he ate, including some very bad places. Needless to say, this makes for interesting reading.

In his 1969 UG, R. B. Read made a case that the San Francisco area had a unique set of restaurants from all over the world, such as at The Tortola, which preserved “hacienda cookery” from the days before gringos settled in the state. He also heaped praise on restaurants that were rare in the U.S. then — from Korea, the West Indies, and Afghanistan. The latter instance, Khyber Pass, offered a “fabled” ashak, which he described as “aboriginal ravioli.” In a different category of unusual was The Trident in Sausalito, with jazz and a “debonairly eclectic” menu with a psychedelic design.

Because my copy is the third edition of the New York UG (The All New Underground Gourmet, 1977), I did not get the flavor of the earlier versions, which is a shame. Sadly, Jerome Snyder died during the publication of the book. That and rising prices may have cast a pall over this edition, which strikes me as less interesting than the New Orleans and San Francisco UGs. The original NYC book contained 101 of the best low-cost eating places (out of 16,000!). The third edition has about 130. The three given the highest ratings for “excellent food” were the Italian Caffe da Alfredo, and two Greek restaurants, Alexander the Great and Syntagma Square. Mamma Leone’s showed up in the book even though it met the price criterion only for its Buffet Italiano Luncheon where for $4.25 it spread out 25 feet of salami, mortadella, meatballs, celery, olives, green bean salad, and more.

The UG authors for Boston were Joseph P. and E. J. Kahn, Jr.; Washington D.C.’s were Judith and Milton Viorst. Both books show a lower level of enthusiasm. The Viorsts admitted that Washington “has not been known for its restaurants” and that of the 100 restaurants they visited, “a substantial proportion were so awful that we were unable to include them.” Father and son Kahn began by telling of a long-time resident of Boston and Cambridge who couldn’t imagine that anyone could recommend inexpensive restaurants since the area’s expensive restaurants were “bad enough.” The Kahns then admitted, “It is probably true that the Boston area does not loom large in the world of cuisine.”

Despite their reservations, the authors of both books managed to find some places they liked. The Viorsts singled out five D.C. restaurants as “great finds.” They were: the Calvert Café, an Arabic place “worthy of shahs and empresses”; Don Pedro, Mexican, with a marvelous mushroom appetizer called hongos; the Cuban El Caribe, featuring raw Peruvian-style fish cubes in lemon-onion sauce (95¢); Gaylord, an Indo Pakistani restaurant with “delicious samosas”; and Warababa, a West-African place run by a Ghanaian couple with “exquisite” dishes such as peanut butter soup and Joloff rice flavored with bits of beef and vegetables.

The Kahns didn’t exactly rave about finds in Boston or Cambridge. But, after encountering “enough blandness while making our rounds to put us to sleep,” they enjoyed spicy lamb stew at Peasant Stock in Cambridge. They included the No Name restaurant on Fish Pier – no name, no sign, no lights, no decor — where a seafood chowder (50¢) served as the house special and was “so incredibly rich and so brimming with hunks of fresh fish that a cupful could be a meal in itself.” But the popular Jack and Marion’s in Brookline, known for its giant menu and huge portions, ranked merely as one of the area’s “better delicatessens.”

Alas, I couldn’t find the books from Honolulu, Los Angeles, or Long Island, but I saw a magazine piece that criticized the Los Angeles UG for its surprising inclusion of 25 restaurants in Palm Springs.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022