Jan Whitaker's Blog

November 2, 2025

A grandiose failure?

It’s difficult to assign a definite cause to the short life of Raphael’s, a Chicago restaurant that opened in October 1928 and seemed to have closed by the following July. It would make perfect sense if it had failed after the Wall Street crash at the end of October 1929, but it seems to have closed while the boom was still in progress. [Above: Detail of a platter from Raphael’s shown below, with a fanciful depiction of the building.]

Then again, Prohibition was in effect and that almost undoubtedly contributed to failure. But whatever the cause, Raphael’s on Chicago’s south side didn’t even make it to its first birthday as far as I can tell.

Judging from its exotic design, the restaurant clearly had grand aspirations. Its financial backing totaling $300,000 amounted to a small fortune at that time, equal to nearly $5,700,000 today. At least two thirds of the capital came from a major Chicago investment banker. The remaining $100,000 presumably was furnished by the restaurant’s nominal owner, Edwin Raphael.

In June of 1928, as construction began, the Chicago Tribune ran a snarky story that managed to insult the design as well as Chicagoans’ taste in general. It said that the building “should make one think he’s in Persia, provided he doesn’t know too much about Persian Architecture,” and that it was aimed at “Chicago’s epicureans – if we have any.” [Above: Raphael’s main dining room in 1929]

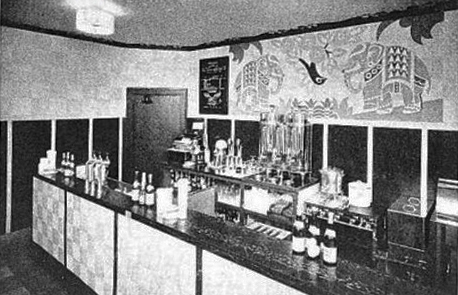

The layout of the building accommodated a small tea garden inside the front door that was outfitted with trees and fountains. Next came a two-story dining room accommodating hundreds, with a ceiling imitating a blue sky with twinkling stars and surrounded on all sides by a balcony that also held tables for guests. Two ends of the building provided people entering from the street access to two interior lunch counters with soda fountains. [Above: one of the lunch counters, but looking strangely like a bar.]

With its minaret, the building reached 60 feet in height and was visible for miles along all three major streets that crossed there. The minaret was used for advertising with neon lighting and a crescent on top. The illustrations used for this building, whether on the restaurant’s dinnerware [shown above] or in advertising, took great liberty in portraying it. [Below: April 1929 advertisement that imagines the building with two domes, four minarets, and palm trees!]

The main dining room featured a band named Raphael’s Persians. Their performances could be heard on the radio at night.

The March 1929 issue of The American Restaurant Magazine hailed Raphael’s for its ability to merchandise meals by “stealing the thunder” of night clubs and offering them stiff competition while putting food “foremost.” When the radio audience listened to the Raphael’s orchestra, the story said, they would feel that the restaurant had “an air of mystery about it” and want to visit “Chicago’s most exclusive restaurant.” But did they?

The combination of three types of eating places in one business was an odd one, something that would be more understandable in a hotel than a restaurant. It would seem as though the tea room and the snack bars would keep earlier and shorter hours than the restaurant/nightclub which stayed open until 3 a.m. and that this would cause staffing problems. By June of 1929 Raphael’s had figured out more ways of making money, as is shown on the advertisement below, such as afternoon dancing, an additional cover charge, and higher cover charges on weekends, but it’s likely that it wasn’t enough.

The trade journal also hailed Raphael’s for its modern kitchen facilities that were filled with the latest mixing machines, ranges, refrigerators, warmers, etc., proving “that the kitchen methods of this modern restaurant are a far cry from the methods employed when the members of Persian tribes would prepare feasts for their shahs.”

A reader of The American Restaurant would be left with the idea that Raphael’s was an elegant place catering to a clientele with sophisticated tastes. But that idea was dashed in a story written by a young reporter who spent a night there playing the part of a “shy cigaret girl.” Over the course of the evening male patrons hit on her nine times. She also observed people drinking alcoholic drinks, probably enhanced by their own whisky flasks. The crowd included teenagers. By June of 1929, the restaurant was reduced to featuring a “crystal gazer” on the balcony named Allah Mahalla. So much for elegance!

Despite serious searching I could find no advertising, nor any mention of the Raphael restaurant at all after July, 1929. In 1940 the address was mentioned as the location of a bunco party (a dice game) hosted by a political group. In 1947 the building, then occupied by a beauty supply warehouse, was auctioned for taxes. It sold for a mere $14,027 plus payment of back taxes of $11,259. The second floor was offered for rent in 1948, and it may have been then that the American Legion moved in. [Above: Could the Hippodrome have occupied the building when this advertisement ran in 1938?]

However, according to a recent Chicago Sun Times story by architectural critic Lee Bey, Raphael’s continued in business until WWII, and “later converted into the American Legion South Shore Post 388.” I haven’t been able to find out why he thought Raphael’s stayed in business that long.

Another eating place that might have once occupied the building (in addition to the Hippodrome) was the Kickapooo Inn. Its address was given as 7901 Stony Island in a 1957 obituary notice for its owner.

The building was acquired by The Haven of Rest Missionary Baptist Church in 1966 and used for church services until 1977 when they built a new church. Now the church is seeking a grant to restore the building, hoping it can be reopened in a few years as a community center. [Above: the building as it appeared recently.]

If any reader has information about this building and its uses over time, I’d love to hear from you. It could assist the church in applying for grants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

October 6, 2025

Newspapers & restaurants

Newspaper workers, especially reporters and pressmen, made up a significant part of urban restaurant patrons in the 19th century and much of the 20th. Early on most of them were men, dropping in at all-night eateries of which there were many. Such eating places tended to choose locations close to the newspapers which were often grouped together in areas of a city referred to as “newspaper row.” [Above: advertisement for a Kansas City MO restaurant, 1940]

In his book Appetite City, about New York’s restaurant history, William Grimes notes the importance of newspapers in building nationwide interest in that city’s restaurants. He observes: “From the 1830s on, New York spawned so many papers and journals that their employees and writers constituted a sizable market, concentrated for the most part along Park Row. Moreover, journalists tended to regard oyster stands, saloons, food markets, and cafes as good copy. As the city grew and restaurants of every description proliferated, journalists turned out colorful slice-of-life stories for local and national consumption.” [Above: early 20th century postcards of newspaper rows in NY and San Francisco]

The restaurants that the newsmen patronized in the 19th century tended to be of two kinds. Either they were no frills, quick-eat places of the kinds newsboys favored, or they were places popular with artists, actors, and other free-wheeling sorts. For their evening meals, when newsmen were on their own time, they were said to enjoy the latter type of places where “there was no style, but plenty of ‘atmosphere’” such as the German “Kitty’s” on Park Place in New York with its Weiner Schnitzel and noodles.

One of New York’s best known hangouts was Bleeck’s [pronounced Blake’s] Artist and Writers, where reporters from the New York Herald were said to dominate. From its beginnings in 1925 until 1934, part of which time it was run as a so-called club in order to avoid the liquor ban, it barred women. Finally they were admitted, inspiring the unfunny comment from an old-time member, “There’ll be mayonnaise on the steak next week.” [Above: newspaper men play game to determine who will pay for drinks at Bleeck’s, 1945]

Another thriving New York restaurant with multiple locations, Crook & Duff, had a restaurant in the basement of the Times building for decades. Other magnets for newspaper folks included Jack’s, Hitchcock’s beanery, and Stewart’s in Sheridan Square. Childs’ in the Madison Square Garden building was a gathering spot for columnists, drama editors, critics, and press agents.

What might be called the Jewish newspaper row in New York was on the lower east side, which over time housed papers such as the Yiddish Daily Paper, Truth, The Day, Morning Journal, and The Forward. The Forward was located on East Broadway near the Garden Cafeteria, a gathering place for activists, intellectuals, and newspaper people, among others.

Of course New York was not the only city where newspapers, their employees, and restaurants were linked.

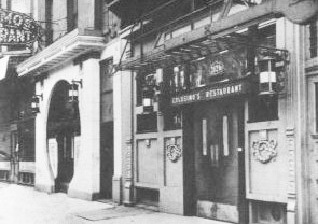

In Chicago, Schlogl’s, an old 19th-century restaurant, served as the newsmen’s club, watering hole, and dinner spot in the 20th century. Also known as Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese Tavern of America, it was located near the Chicago Daily News where its big round table hosted Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters, Ben Hecht, Thornton Wilder and other writers who worked for papers. But there were numbers of other places feeding reporters and printers, such as King’s, run by Mary King in the old Herald building. One of her daughters became a newspaper editor.

Boston had Thompson’s Spa. But as early as the 1870s, the editor of the newly founded Boston Globe established a lunch table at a nearby restaurant that endured for decades, hosting judges, lawyers, journalists, and business men. By the 1880s, Boston’s newspaper row was filled with dairy lunches and “temperance lunch rooms.” Other favorite day and night spots with the newspaper crowd were the various locations over time of Mrs. Atkinson’s, where baked beans and brown bread, corned beef hash, pies, and doughnuts were in demand for nearly 40 years. From the 1880s until 1919 Vogelsang’s was not only an eating place for newspaper men, but also for Democrats, making it a source for contacts and stories as well as for meals. [Above: Gridley’s in Boston’s newspaper row, early 20th century]

For decades in the teens and 1920s, and probably the late 19th century as well, Washington D.C. newspaper men enjoyed the French restaurant run by Count Jean Marie Perreard. He was known for his Bastille Day parties, where a tall Bastille made of boxes would be built in a corner to be attacked by guests at midnight.

St. Louis had Thony’s, where 19th century newsmen mingled with merchants and bankers while enjoying oysters brought from New Orleans on steamboats. Other newspaper men such as Eugene Field, an editorial writer in the 1870s, enjoyed the Old Beanery.

In the 1870s, Philadelphia newspaper workers almost certainly would have been found at the Model, which fed about 2,300 a day, joining a crowd that included the “sons of toil.” In the 1890s the quick lunch places grouped around the city’s big stores and newspaper offices would also have drawn them and it’s almost certain that later they would have flocked to the Horn & Hardart Automat opening in 1902. But the anti-alcohol emphasis of the city may have discouraged clubbiness.

Frequent employee patronage of eating places was only one way that newspapers influenced the restaurant world. Not only did the papers report on restaurants and carry their advertising, over time their role in promoting, evaluating, and rating them grew. Eventually there were formal reviews, and also gossip columns whose one-sentence quip about a well-known celebrity spotted in a restaurant was often enough to build the restaurant’s desirability and familiarity with readers across the U.S.

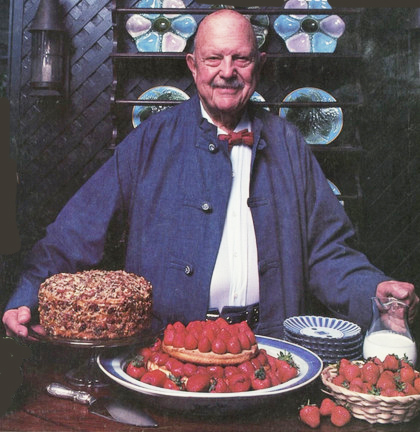

In the mid-20th century food columnists gained prominence. In 1962 Craig Claiborne began regular restaurant reviews for the New York Times. New Yorker James Beard [above] covered not just his city but the nation, running columns in many papers. When columns featured recipes, they almost always praised the restaurants that supplied them. And as has been observed by others, newspapers across the country were inclined toward favorable reviews for restaurants that were regular advertisers.

Restaurants began to turn to newspaper advertising in the 1920s, considering that the best way to attract customers. Almost certainly the most frequent advertiser nationwide in that decade was the low-priced Waldorf System with 94 units spread across 28 cities. Waldorfs were not fancy, but according to their ads they were extremely clean, with each unit undergoing inspection four times every 24 hours.

With the diminishment of newspapers, restaurant gatherings also ended by the later 20th century as did men’s clubs generally.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

September 22, 2025

More about odd restaurant names

When I started looking up strange business names for restaurants I was thinking this was something in the past. I was so-o-o-o wrong. It’s impossible to say how many there are – or how many there have ever been, but now I’m convinced that they are as popular as ever, probably even more so than in the past. [Denver Post comic strip, 1997]

This was strongly confirmed when I discovered a current that is dedicated to helping people find the right name for their new restaurants. It lists over a hundred novelty restaurant names that were operating at the time the site was created. Some are clever, some are ultra-corny, and some are borderline objectionable. I don’t think any of them would draw me in because of their names alone.

In the past – probably beginning in the 1950s, odd restaurant names were still unusual enough that newspaper columnists would write about them. It was considered newsworthy or at least unusual enough to attract readers. That focus would tend to be ridiculous today because it’s no longer much of a novelty to have a strange or comical name.

Also, it now seems quaint that in 1957 a columnist for a paper in Washington thought that the restaurants opening in a Sheraton Hotel were “unusual.” They were Café Careme, Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, and Indian Queen Tavern. Today they don’t seem unusual at all.

As I look over my notes and an , I realize the attraction to whimsical names began in the early 20th century, with tea rooms prominent among them. Aside from them, most of the restaurants that adopted funny names were casual eateries, not formal or expensive restaurants. That is probably the case today too. [Above: 1921 advertisement from a Norfolk VA newspaper]

Places that made fun of themselves could have a strong attraction, with Ptomaine Tommy’s, dating back to 1913, being a prime example.

In one notable case, an odd name caused problems for its owner. A restaurant in Detroit was losing customers in 1970 because it was named Mercury Fish and Chips. Trouble was that this was the time when mercury was being discovered in fish in Lake Erie and other lakes. She was losing about a fifth of her business because of this. The name was not even meant to be cute but had a name that mainly indicated it was a fish restaurant. She had kept Mercury in the name because that was the name of the very popular restaurant that preceded hers and she thought it would be a draw.

In another case, the strange restaurant name Le Garbage, as well as its location 200 feet from a sanitary landfill in Pennsylvania would have seemed to be a guarantee of failure. But it was a very popular truck stop with its customers, trash haulers. They found it all funny, including the joking observation about food being brought in fresh daily.

A popular trick name for a restaurant is The Bank, which allows related naming for everything on the menu from main dishes such as Money Bags and The Stick Up, and side dishes under the heading Loose Change, as in a 1970s menu of an Indiana restaurant.

It’s almost needless to say that odd, funny, or even puzzling restaurant names are meant to draw attention, stand out in the crowd, and perhaps lure curious customers. With the increase of restaurants over time, it may seem more necessary than ever to have a name that is comically appealing. But, how well does this actually work? Hard to say.

Clearly there are some who enjoy them while others are going to avoid them, reasoning that the emphasis is on cutesiness rather than cuisine.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

September 7, 2025

Heroism at Lunch, cont’d.

I am republishing this post that I originally presented ten years ago, because of the September 4 death of Joseph McNeil, age 83. The Greensboro lunch counter has been on exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. since the 1990s when it was acquired from Woolworth’s. It will be one of 250 items featured in a show of “revolutionary objects” at the museum in 2026.

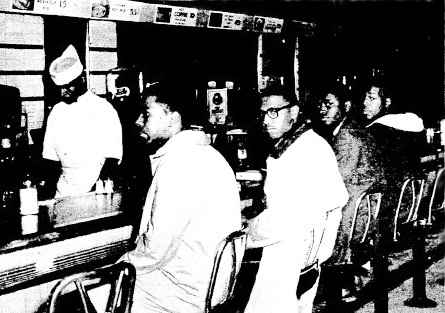

Actually there was no lunch. But there was plenty of heroism when four college students sat at a Greensboro NC lunch counter in February 1960. [Above photo: Joseph McNeil is seated on the left.]

The students were told to go to the segregated snack bar in the back of the Woolworth 5 & 10 cent store, but they refused. And although the Woolworth staff would not serve them, the students also refused to leave until closing time and pledged to come back every day until they won the right to eat there.

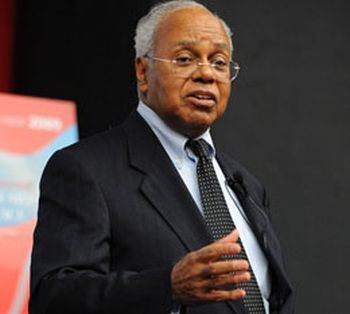

It was an honor to hear one of the organizers of the protest at the 9th Annual Northeast Regional Fair Housing and Civil Rights conference in Springfield MA. Joseph McNeil [shown above at the conference] told a room of 500 attendees how much had hung in the balance for him at the time. A first-year student at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, he feared that he could end up in jail and disastrously interrupt his college career. (Fortunately, his fears were not realized and he went on to graduate and eventually become a major general in the U.S. Air Force.)

McNeil related how the Greensboro protest grew as students from area schools joined with the initial four, then more student protests erupted at Woolworth stores around the South. In July 1960 Woolworth reversed its policy, which had been to let local managers decide whether or not to serve Black customers based on local customs.

He explained that the sit-down protests served as “a down payment on our manhood and womanhood” for him and his fellow students. The action, he said, was driven by their belief in the “dignity of men” and “the moral order of the universe.”

In the Q & A after his talk, a woman in the audience asked what his mother had thought about his decision to join a sit-in at the lunch counter. He said she had been uneasy about it but had to agree that it was the right thing to do based on the values she and his father had taught him.

McNeil received repeated standing ovations from conference goers. Everyone laughed when he said that he had always wanted to order coffee and apple pie at a Woolworth lunch counter but when he did, “The apple pie wasn’t very good.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

August 25, 2025

Restaurant psychology

My last post about a restaurant designer who applied psychology to his work inspired me to look further into this subject.

I discovered that when the restaurant world was experiencing hard times there was a turn toward psychology, though of course that wasn’t the only inspiration. In the 1920s, when liquor sales became illegal, expensive restaurants were inspired to look harder for ways to please their guests. A proprietor whose famous eating place had to close warned others that “What the restaurant loses in the revenue from wines and liquors it must make up in psychology.” Evidently in his case, this realization came too late.

Canny cafeteria operators, though never dependent upon liquor sales, were already using psychology on their guests in the 1920s. And as early as 1927 a psychology professor appeared at restaurant conventions to give attendees help in figuring out “What do people like and why?”

Psychology often veered into what I would call blatant manipulation, for instance in cafeterias. Cafeterias tried such things as enlarging trays so they looked empty unless the customer loaded up. They also placed desserts on eye-level shelves that were the first thing the hungry customer saw as they entered the cafeteria line.

In later years other manipulative ploys in everyday eating places would include uncomfortable seating and bright colors that shortened customers’ stays, as I have previously written about.

The Depression and WWII put a damper on psychology advising, but it returned in the 1950s. A strange example was a Hollywood therapist who made a practice of visiting a restaurant called The House of Murphy. He went table to table giving customers, many of them actors, his analyses of their psyches. I would not think they appreciated some of his insights, such as when he told Gary Cooper that he was a “withdrawn introvert.” As for dining, his verdict was that “A very large meal is an escape mechanism.” As he saw it, “The customer is gorging himself in order to have a sense of security and power.”

Other restaurant psychologists turned to writing columns for newspapers. Dr. George W. Crane, for instance, focused on sloppy waitresses who failed to meet his standards, that of a “glorified mother.” “And be sure to smile,” he advised them, “for this makes you a psychotherapist who helps the morale, appetite and even the digestion of lonely, moody and fearful souls.” All for 50 cents an hour?

By the 1970s restaurant psychology had taken leaps forward and was a tool of restaurant designers, beginning with interior and exterior design and assistance with restaurant concepts, naming, advertising, and public relations.

In 1977 David Stevens, then considered a leading restaurant designer, had a hand in the design of 100 restaurants, including fast food chains Hobo Jo, Humpty Dumpty, the Mediterranean in Honolulu, and a number of Bobby McGee’s, as well as the Mai Kai in Fort Lauderdale [shown below]. He believed a restaurant had to be in tune with the “emotional trend of the nation.” In 1977 he favored nature themes and booths to “give the public something to lean on” at a time of nationwide insecurity due to a weak economy. Though he declared that the rustic look was “out,” he admitted that heavy beams could sooth tension.

Another slant on booths came from a designing couple who proclaimed that they served as “a womb surrounding and hiding customers who don’t want to be seen, especially if they’re a little overweight.”

Plants were tricky according to some. In 1980, the part owners of Ruby Tuesday’s Emporium noted plants could be used very strategically. “If you’re aiming for college-age patrons,” they advised, “there should be floor plants.” On the other hand, young professionals liked hanging plants which they said, “denote a higher degree of sophistication.”

In 1983, restaurants had not recovered from the recession of the previous year. In Broward County, Florida, with its 2,600 restaurants, there was a high failure rate in the first year of the recession. Some restaurants sought help from an industrial psychologist who trained staffs in empathy with the customer, and taught them to how to handle uncomfortable situations.

The emphasis stayed on servers at the National Restaurant Association’s annual conference the following year. A psychology professor from Denver’s School of Hotel and Restaurant Management was on hand to instruct participants in their “real” business: not selling food and drink, but in fulfilling people’s needs. Servers were to smile, answer questions, and show interest in what the customer was ordering. They were to nod their heads, and say “I see“ and “uh-huh.”

Of course, by this time it was taken for granted that interior design was important. In 1984 some thought that the nation was “longing to return to simpler times.” In design this was frequently interpreted as early-American themes, barn siding, and huge beams.

But in Houston a design team had a very different interpretation. They preferred to give new restaurants a worn, slightly dirty, look. To achieve this they gave walls a few stains and planted handprints around light switch plates. Customers were to feel they didn’t have to be super careful, that spills were perfectly ok. The Atchafalaya River Café gave an aged look to the building formerly occupied by the Monument Inn. They covered part of the roof with battered tin, deliberately left paint splatters on the front window, and used old doors for the front, pasting them with bumper stickers, all in the belief “that tacky, comfortable design makes people happy.”

Why not a country theme? Well, as the designers of the Atchafalaya River Café liked to say: “Pastoral scenes are deadly to a good time in restaurants. Customers feel mother or grandmother is watching every move.”

Bringing another sense into play, noise became part of design in the 1980s. Designer Leonard Horowitz said in 1986 that at the Crab Shack in Miami, where diners smashed crabs with wooden paddles at their tables, “ear-splitting volume is one of the things that makes the Crab Shack so popular with many of its customers.” He thought it was because people “enjoy feeling like part of a party or performance.” He also noted that while noisy spaces felt festive they also encouraged quick turnover, which of course greatly enhanced profits in popular places.

By the late 1990s, and very likely before that, having a professional designer versed in restaurant psychology was common, particularly in the case of restaurant chains. That was especially true in restaurants that aimed to entertain as well as to provide food. The word for this is “eatertainment” in recognition that food is only one reason that people patronize restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

August 4, 2025

Fear of restaurants?

In a talk he gave at the National Restaurant Association convention in 1965, restaurant designer Richard Kramer observed that “Eating and drinking are anxiety-evoking situations that reduce man’s independence and make him regress to a child-like dependency.” Going into a restaurant made him feel “angry because he is hungry and also dependent on someone else to feed him.”

I find it so interesting how he linked anxiety and anger, not to mention restaurants and anger.

He applied this mostly to men. By contrast, I would think most women then would have felt grateful and relaxed when going to a restaurant because someone else would be doing the cooking and clean up.

Kramer, who said he had studied psychology and psychotherapy, had a very successful career as a restaurant designer and founder of Integrated Design Associates in Los Angeles in the 1960s. The company continued in business long after he retired in the 1980s. IDA won 6 of 19 awards given by a national magazine in 1964, two of them for the restaurant El Gaucho in Beverly Hills’ Wilshire House [shown above].

In addition to El Gaucho, IDA’s clients included Hyatt Hotels, a couple of Playboy Clubs, the Balboa Bay Club, Chez Voltaire in the Beverly Hills Rodeo Hotel, the Little Corporal in Chicago, Quivira Inn in San Diego, Dobbs Houses at the Dallas/Fort Worth Airport, eating facilities in the Air Resort Hotel in Fresno and the Friendship International Airport in Baltimore, The Lodge of the Four Seasons in Missouri’s Ozarks, and a number of western Sirloin Pits.

After reading Kramer’s approach to design I could only wonder what his interiors looked like. Although I could find very few images of restaurants he designed, I noticed that he seemed to like to use the color red, a color that has been linked strongly to mid-century restaurants especially attractive to male diners. I was surprised when I saw the red interiors, mainly because I don’t see redness as soothing. But perhaps the role of red in restaurant decor was to suggest luxury more than to soothe an anxious, angry diner. [above: Chez Voltaire]

His observations were that people eating in restaurants “want to be taken care of in a basic psychological sense.” They choose restaurants that make them “feel secure.” But he was also aware that a restaurant had to present a sense of luxury if guests were to “enhance their status and bolster their egos.” He wrote that “The designers’ task was to find a balance between extravagant formality and boring familiarity.” Otherwise their interiors might fail to “activate a buying mood.” Another hazard was that the diner might decide that a restaurant served bad food, according to Kramer, who declared, “To any angry, anxious person, the best food can have no taste except bad.”

Who knew that the stakes in restaurant design were so high?

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

July 20, 2025

What was a restorator?

The early French restaurants in this country probably were the best places to eat in the late 18th century and early 19th. Along with gourmet food (they said), they offered to improve the health of ailing patrons. This was in keeping with restorators in France at the time. [Above: part of an 1800 advertisement for a new Portland ME restorator]

Among customs that differentiated restorators from eating places in general was their soup. As in France in the early days of the development of the restaurant, soup was an important part of the business. It was meant to restore health, leading the eating places that specialized in it to call themselves restorators.

Restorators in this country offered other dishes as well as soup, of course, but the fact that they served soup tended to set them apart from other eating places which generally did not offer it at that time. Julien, whose restorator is considered the country’s first “restaurant,” was known as the “prince of soups.” His soups included barley, turtle, and “brown soup,” which was a beef consommé. Like many restorators, he also offered alcoholic beverages including wine.

Most of their advertising does not mention cost, however one that does quotes shockingly high prices in 1797. A Philadelphia restorator named Bossee offered “Jelly Broths, and every thing that may be wished for, as well Liquors and Meats of all kinds. Exactly at Three o’clock there will be a Dinner served, at One Dollar for each person, with half a bottle of old Bourdeaux wine.”

That, and a few comments I’ve found from the days in which they flourished suggest that restorators were patronized by men who were wealthier than the average.

Of course, restorators also provided a wide range of dishes beyond soup. Pastries were specialities too. Boston’s Dorival & Deguise advertised in 1796 that they furnished “every thing that the season affords, such as Meat, Poultry, Fish, Vegetables, Fruit, etc., which will be varied with a great variety of excellent Creams, Pies, Cakes, etc. – such as never fail of pleasing the palate of Gentlemen who are in, or out of Health.” Note that American cooks of that time were not known for their skill in creating pastries.

The custom of many restorators of providing alcoholic beverages put restorators on the list of objectionable public resorts in the eyes of the anti-alcohol forces that gained strength in the 1830s. A magazine titled The Youth’s Companion published an article in 1837 that worried about how (male) youth would spend time “at the fashionable ‘Restorator,’ where the taste of its delicacies and the fumes of the wine cup and the cigar will soon obliterate the salutary impressions you may have received by reading the Youth’s Companion, or at the Sabbath School.”

It is true that the period in which restorators flourished in cities was in fact considered by historians as “probably the heaviest drinking era in the nation’s history.” [Drinking in America, Edward Lender & James Kirby Martin] But most heavy drinkers were imbibing liquor, not wine.

Nevertheless there were still places called restorators as late as the 1880 census, though maybe they were just restaurants calling themselves that, or a designation made by old-fashioned census takers. Advertisements did not mention soup or an emphasis on health beyond the 1830s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

June 30, 2025

Popcorn at the movies

Popcorn isn’t a meal, and a movie theater isn’t usually (with a few exceptions) a restaurant, but it’s summer and my mind is straying. I became curious about how popcorn got so popular with movie goers.

Turns out that popcorn in theaters was a topic destined to become a popular topic with journalists. Columnists were attracted to it, and newspapers often raised the question of popcorn eating in their “people on the street” surveys.

There seemed to be quite a lot of people who strongly disliked listening to popcorn crunching in theaters. And before popcorn boxes and tubs were introduced they also complained of the rattling of paper bags that popcorn was served in.

The earliest complaints I found began in the teens. But long before people began complaining about popcorn in theaters, they complained about peanuts. As early as 1865 a story titled “The Peanut Nuisance” appeared in a New Orleans paper. Of course the theater would not have been showing movies then, but the complaint foreshadows the popcorn debate. The theater goer wrote: “. . . we hold that no gentleman will eat peanuts in a theater. No man can be a gentleman who, for a little self-gratification, will annoy and disgust all those around him.”

Popcorn came to theaters in the early 20th century. Already by 1916 the Majestic theater in Monticello IN was popping and buttering corn with a newly invented “beautiful” electric Butterkist popcorn machine [shown above] that stood proudly in its lobby. The Monticello Journal remarked that the theater was now “in line with the progressive picture houses of the big cities.”

It didn’t take long for complainers all over the country to register their opinions. A letter to the editor of a newspaper in Stockton CA announced that the writer disliked the “rattlings, scrunching and smacking” so intensely that they could barely restrain themselves from “having a violent fit.” By the 1920s commentators were calling popcorn eating at the movies a “craze.” Still, negative reactions filled papers across the country for decades, finally beginning to die down in the 1960s.

Some theaters also disdained popcorn. The Loew’s theaters took the initiative in prohibiting patrons from eating popcorn in their theaters. Not only did the theaters not sell it, they asked anyone bringing it inside to check it. The name of the owner was written on the package and it was returned after the showing.

The official response to complaints about popcorn in theaters included exploring the possibility that popcorn drew rats. The Wichita KS city council, for example, asked the health department to investigate this risk in 1939. No evidence that popcorn threatened health was found.

Even without rats as an excuse, some officials took the route of outlawing popcorn in movie theaters. In the late 1940s there were attempts to pass state laws to ban popcorn in movies in Oregon and Wisconsin. They went nowhere.

Theaters insisted that they needed the revenue produced by their refreshment counters — where popcorn was the big seller. In 1946 a theater in San Diego admitted that one week their candy counter took in more money than the movie that was playing. By the early 1950s concession sales were seen as essential for economic health, all the more so as television became common. A story reported that an accountant representing theater owners told the House Ways and Means Committee in 1953 that “only popcorn and candy had kept the movies in business during the last two years.”

The popcorn wars came to an end. If some people disliked popcorn crunching they kept it to themselves.

Public attention turned to what kind of movies stimulated popcorn sales most successfully. Gangster and cowboy movies and musical comedies were said to rate highly unlike “the serious and thought-provoking types.” Elvis movies were said to sell the most popcorn in 1956 and 1957. The Exorcist was the winner in 1974 and Jaws was said to be the “popcorn picture” of all time. Some psychologists were of the opinion that the hand-to-mouth activity was soothing.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

June 16, 2025

Colosimo’s charm

Many restaurants through the decades have built their popularity on a genial host. That was true of Colosimo’s in Chicago and its owner and host Jim Colosimo.

To a large degree the restaurant’s reputation was built around “Big Jim.” Before 1920 that was because of his pleasant manner. And, maybe, the spaghetti at Colosimo’s really was exceptionally good.

But the genial host was also a big-time gangster.

The restaurant was located in a part of Chicago known as the levee, an area specializing in prostitution. Colosimo had opened his restaurant in 1910, having previously run two “single-hour” hotels.

He expanded his operations to become a crime boss who not only provided illegal services but also had procurers recruiting naive young women as prostitutes in and outside of Chicago. And he handled the police, seeing to it that they didn’t interfere with these activities. His lieutenants collected payoffs from other illegal operators — and killed people as necessary — leaving Big Jim’s hands clean. (Of course, the police knew very well what he directed his minions to do.)

Many of Colosimo’s patrons also must have known about his other activities. In 1914 a letter appeared in the Chicago Tribune from a woman who feared for the fate of young women that might venture into the place:

I have been reading The Tribune about this vice upheaval and notice what is said about Colosimo’s. This recalls that when I first came to Chicago last winter I saw, I believe, [full] page ads in the leading Chicago theater programs which advertised what a fine place was to be found at Colosimo’s. I didn’t know what kind of a place it was and didn’t go there to find out, but I’ll warrant any number of younger girls went there, led by the page advertisement in the Chicago theater program, and undoubtedly a great many of them can now trace their downfall to Colosimo’s. [above: 1914 advertisement]

Its reputation evidently didn’t bother many of its patrons. The theatrical profession was said to flock there. And a publication reported that “The café . . . is crowded nightly after the show with a merry making throng which makes it one of the brightest spots on the city’s map.” It served as an ongoing attraction for the city’s “society slummers.” And in 1916 an advertisement for Colosimo’s appeared in the Official Program of the Republican National Convention to be held in the city.

His execution helped perpetuate the restaurant’s appeal after Colosimo was gunned down on the premises in 1920. It also helped that Al Capone was associated with the restaurant. He had been hired as Big Jim’s bodyguard, replacing him as the city’s crime boss after he was killed.

In subsequent years the name of the restaurant remained Colosimo’s, despite his absence and a new owner. It was remodeled to look elegant, and operated as a nightclub. Its past, presumably firmly behind it, did not deter the crowds in the 1920s. Drinks were available, although the restaurant was shut down repeatedly for violating Prohibition. Apparently that was okay with the alumni of a Vermont military college which planned a dinner there in 1925, including their “wives and sweethearts.” Their invitation noted “At this place we can be entertained by dancing, eating and looking . . .” [my emphasis]

The new owner, who had bought a half share in the restaurant shortly before Colosimo’s murder, operated it until its end in 1948, by which time it had suffered the bizarre fate of being converted into a cafeteria. [Above: the restaurant in the 1940s]

Colosimo’s murder was never solved.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

June 1, 2025

Famous in its day: Café Johnell

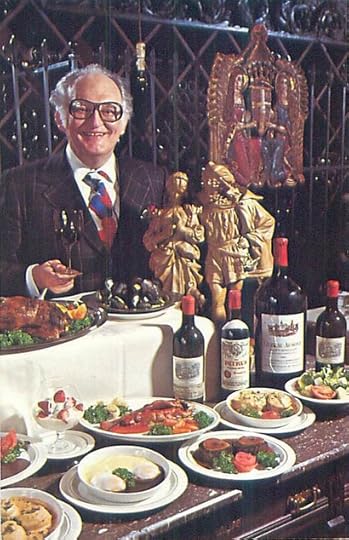

John Spillson came from a restaurant family, so it’s not entirely surprising he went into the business himself, eventually establishing the Café Johnell in Fort Wayne IN in the 1960s and winning endless awards through the years. [Above: ca. 1974]

And yet his path to success was surprising. After working at his father’s restaurant in Fort Wayne, the Berghoff Grill and Gardens, until WWII, he opened his first restaurant in 1951. It was called Meal-A-Minute. I could learn nothing about it other than it went bankrupt the following year.

In 1956 he had a new restaurant, Big John’s Pizza on South Calhoun, at the same address that would one day become Café Johnell. (The nickname “Big John” stuck with him for many years, referring to his height and overall size.)

In 1960 John opened a second pizza outlet on North Clinton. Soon he began to transform the South Calhoun pizza place into an Italian coffee house called Café Johnelli. When a local columnist visited it he noted that it served a variety of coffee drinks as well as an unusual lettuce salad, and baklava for dessert. He concluded that dining at Johnelli’s was “new and different” and “a rare treat.” In 1962 the size of the coffee house doubled and a year later John dropped the I from Johnelli.

In 1963, he adopted a French identity for the restaurant. As he explained it, “I dropped the Italian food because of the Kennedys. They were serving French food in the White House and wine with dinner. I looked at all the publicity they were getting; the public wanted to do what the Kennedys were doing. . . . So I . . . .decided to go French.”

As The Holiday Magazine Award Cookbook noted in 1976, the pizza parlor was “reincarnated . . . as an elegant French restaurant and [he] ran it with such panache that kings, stars of screen and field, everyone within a 200-mile radius who wanted a truly decent meal, flocked to his Café Johnell. Today, in a city noted for auto pistons, life insurance and high school basketball, it’s Spillson’s restaurant that attracts new top executives.” [Above: advertisement from July, 1959, prior to the transformation]

Holiday Magazine awards were some of the almost uncountable number of awards showered on Johnell’s beginning in the 1960s and continuing over the years. They recognized the restaurant’s coffee, wine, and cuisine. But Johnell did not make it into Playboy’s top 25 restaurants in 1984, instead being mentioned as a “regional favorite.”

As John Spillson grew older he brought his daughter Nike into the restaurant as chef, after she was trained in France’s Cordon Bleu. He also began to groom some of his other children for positions as well. Longtime cook Elsie Grant also visited Paris, presumably under John’s sponsorship, trained at the New Haven Culinary Institute, and apprenticed at Le Mistral in New York and Maxim’s in Chicago. Her career was notable in demonstrating opportunities for professionalization rarely offered to Black women cooks in this country.

Following John’s death in 1995 his children continued to run the restaurant until it closed in January, 2001. In its last years the restaurant’s ratings declined, with many feeling the time for a restaurant of that kind had ended decades earlier. Nevertheless, the restaurant reviewer for the Journal-Gazette, who was quite critical of the restaurant’s decor in later years, praised it after it closed even though she admitted it was “a prime example of a business too long on a respirator.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2025