Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 3

December 29, 2024

Famous in its day: Well of the Sea

A short time ago I had a chance to visit the fascinating second floor of the Fishs Eddy store in New York. It is piled high with not-for-sale dishware of all kinds, collected by the store’s owner Julie Gaines. The collection includes restaurant ware from the golden past when this country still produced such things. (Tours of the collection, hosted by Julie, are given periodically and booked by the New York Adventure Club.)

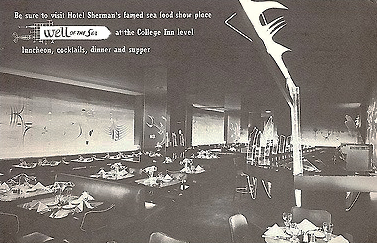

The Fishs Eddy collection also includes records from china producers that show pattern designs. A page from Shenango China in Newcastle PA — closed in the 1970s — depicted the design for a plate made for use at the Well of the Sea restaurant in the former Hotel Sherman in Chicago. (A ca. 1950 painting of the restaurant by Cal Dunn is shown at the top of this page. Below is a plate using the above Shenango design.)

The restaurant opened late in 1948 in the hotel’s basement, which no doubt suggested an underwater theme to the hotel’s owner, the colorful and theatrical Ernie Byfield. He had also originated the over-the-top glamour restaurant, the Pump Room in the Ambassador Hotel.

A number of abstract murals of underwater scenes by Richard Koppe, Chicago painter and student of the German Bauhaus, decorated the walls of the restaurant. One of them was used for the menu’s cover shown below. The room was further enhanced by darkness and other-worldly ultraviolet lighting.

In addition to the murals, Koppe also contributed wire fish and light sculptures somewhat visible in the black and white advertisement of unknown date. The color menu depicted one of the murals.

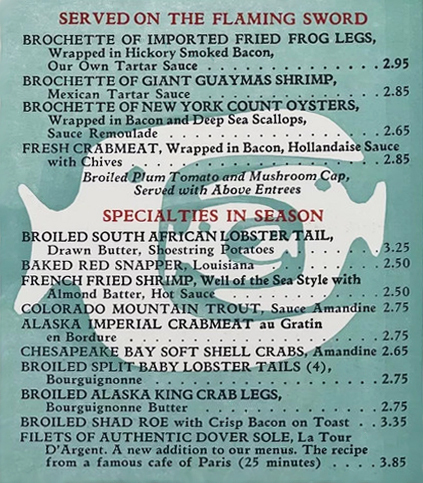

Needless to say, the restaurant specialized in fish, with frequent shipments coming in by air. It was especially known for what was called Black Clam Chowder made with Madeira wine, clams, and many herbs and spices. A portion of a menu is shown above.

Another unusual feature of the Well of the Sea was the attached art gallery in which the work of Koppe and other Chicago artists was displayed. The exhibit of Richard Koppe’s work took place in December, 1949, one year after the restaurant’s opening.

In 1968 the Sherman’s general manager explained that the ultraviolet light used in Well of the Sea was glamorous when it illuminated jewelry and white shirts but not when it lighted false teeth. But the customers liked it anyway despite the room being so dark that waiters had to assist them with flashlights in order to read menus. In 1968 a glow-in-the-dark menu was introduced to make reading easier.

Exactly when the dishware inspired by Koppe’s murals and designed by Shenango Potteries’ Paul Cook came into use in the restaurant is not known with certainty. According to Margaret Carney, whose International Museum of Dinnerware Design in Kingston NY features many pieces of dinnerware from the Well of the Sea, the design shown on the Shenango file page above was probably not used until 1954. What preceded it is unknown.

The Well of the Sea was popular from the start and stayed in business until 1972, a year before the Sherman itself closed.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

December 15, 2024

Continental cuisine comes to Orange County

In the mid 1950s Geril and Gosta Muller arrived on the west coast. They were born in Denmark and had graduated from a Hotel and Restaurant School in Copenhagen in 1943. Following that Geril had served royalty at a Royal Gun Club. [Gosta (left of then-president Nixon) and Geril, 1971, at Chez Cary]

After a few years in Reno NV, they would swiftly work their way to the top of the emerging luxury restaurant pyramid in Southern California, managing and eventually owning award-winning restaurants there.

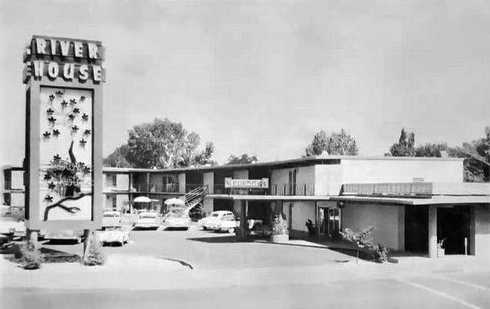

In Reno, the brothers worked at a motel restaurant called The Bundox (meaning boondocks). After a few years Geril went on to San Francisco to work as manager of the Pink Chateau restaurant in the Continental Motel. It may be significant that the Pink Chateau featured steak cooked on a “flaming dagger,” because flaming food would be a featured attraction at their next engagement in Orange CA. There the brothers firmly established their reputations for creating and running fine restaurants. [above: River House Motel, home of The Bundox]

In 1965 the Mullers helped establish Chez Cary, named for owner Cary Sinclair. The Chez, as it became known, set a model for an exquisitely posh and precious style of “continental” restaurant-ing not found much outside San Francisco and Los Angeles at that time. Orange’s residents may have been well off but they were not used to dressing up for dinner. A suit and tie was a requirement at Chez Cary where princely male waiters threatened to outdress their wealthy customers. [1967 cartoon of Geril wearing tuxedo]

The brothers decorated the restaurant lavishly with red velvet upholstered swivel chairs, crystal chandeliers, silver candlesticks, fine china, and old world decorative objects. Geril rounded up a talented kitchen and dining room staff. And, of course, there was quite a lot of tableside theatrics, with salads tossed and dressed, sauces poured, and meats and desserts flamed.

There was a ladies’ menu – i.e., one with no prices — since madame couldn’t possibly be the one paying the bill. And there were ladies’ footstools under the tables. Why the footstools? I don’t know, but they seemed to impress reviewers.

In 1966 the restaurant reviewer from the Long Beach newspaper observed that the bill for a dinner with his wife came to $18 plus tip. But, he wrote, it was the sort of restaurant where guests were not supposed to care what the total came to. He gave it his highest rating: AAAA. While the brothers were at Chez Cary, acting as managers and maitre d’s, the restaurant won four Holiday Magazine Awards, an accomplishment generally attributed to the Mullers.

The Mullers remained at Chez Cary until 1973 when they opened their own restaurant, Ambrosia, in a Newport Beach location formerly occupied by a restaurant called Karam’s [shown above]. Their ability to win awards continued at Ambrosia [below: cartoon of Geril with a Holiday award, 1975].

Ambrosia strongly resembled Chez Cary in luxurious decor and smooth operation. According to one report the restaurant “served so many flaming dishes that at one point it had to get special permits from the town’s fire department.”

Evidently patrons found Ambrosia very comfortable. Five-hour-long meals were not unheard of. By the 1980s the typical tab for two had risen to $150. [Above, Ambrosia in Newport Beach]

But, alas, ten years after opening Ambrosia the building’s owner threatened to double the rent. The brothers hatched a plan to relocate Ambrosia to an elaborate and expensive new restaurant complex they built in Costa Mesa called Le Premier. But Ambrosia didn’t succeed in its new location, closing a mere two years after opening in 1983. Geril bitterly observed that Costa Mesa was not a good location for a first-class restaurant, saying there weren’t “enough well-traveled people in Costa Mesa” and “Anything exclusive will not work there.”

Despite declaring bankruptcy, the Mullers did not give up the struggle to revive Ambrosia. Another restaurateur had adopted the name Ambrosia and the type style the brothers had used. They sued him, hoping to get back the name. Then they bought the restaurant in Newport Beach that had taken over their former location there – 30th Street Bistro — planning to open a new Ambrosia once they won the suit. Sadly for them, they did not succeed.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

November 26, 2024

Goodbye, Alice

Last week Alice Brock of Alice’s Restaurant made her exit from Earth. I wrote a post about her long ago, but thought I’d add a bit more about her life, including more of her colorful quotations. She didn’t find running restaurants easy and made that clear in interviews and in her 1975 book My Life As a Restaurant. [photos by Jane McWhorter, from Alice’s book]

In addition to opening and running three different restaurants in Western Massachusetts over a number of years, she worked with a franchise that was to create nationwide string of restaurants, not surprisingly named Alice’s Restaurant. In 1969 announcements were made that the first four would be located in Boston, New York, Nashville, and Los Angeles. The goal for the first three years was 500! Just how many of them materialized is difficult to determine, but it’s certain the total fell far short.

Alice derived some income from her association with the enterprise. She was paid to be a menu consultant, promoter, and for “just being Alice.” She fulfilled the third goal when she quit the job less than a year after the launch. Once she sampled the food at the New York pilot location she declared, “The food was no good. It wasn’t honest. It was like the movie – a lot of gravy but no meat.”

She spoke her mind, as her quotations make clear.

About her first restaurant in Stockbridge MA:

“. . . a year after I had opened the restaurant, I dragged my body in through the door and freaked out. I felt that instead of owning it, it owned me. . . . I had a terrible urge to smash everything. I telephoned Eastern Airlines and booked myself on the midnight flight to Puerto Rico. I emptied the cash box, gave away all the food.”

Working in a restaurant kitchen:

“. . . if you open the kitchen door, it’s like the door to Hell – everyone’s screaming and crying and cursing, and pots are being slammed around, sweat is pouring off everyone, and it’s a hundred and thirty degrees.”

Running a restaurant:

“Running a restaurant isn’t really satisfying. In fact, next to running a hospital emergency ward, I think this is the worst thing you can do.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

November 17, 2024

Restaurant-ing in movieland

In 1916 a newly arrived New Yorker named Adolph “Eddie” Brandstatter and a partner opened a café in Los Angeles. Modeling it on an unnamed New York City restaurant, they named it Victor Hugo and designed it to introduce fine French cuisine and continental service to the cafeteria-loving city.

Four years after opening the Victor Hugo, Brandstatter turned his attention to a Santa Monica project, the Sunset Inn, buying it with a new partner and selling his share in the Victor Hugo. His short tenure at the Victor Hugo was an early sign of his seeming “love it and leave it” relationship to most of the restaurants he created. Despite that, he rapidly became a well-known and well-liked public figure.

Trying to track all his restaurant ventures is a dizzying job.

By June of 1920 the Sunset Inn, which had served as a Red Cross center during WWI, had been remodeled and outfitted with a jazz band. Wednesdays were devoted to performances by Hollywood actors. But in 1922, less than two years after its opening, and despite the Inn’s apparent success, Eddie sold his share and moved on.

That same year, only a few months after departing from the Sunset Inn, he bought a new restaurant, the Maison Marcell, remodeling and reopening it. A little more than a year later he remodeled it again, renaming it the Crillon Café. Meanwhile, shortly after opening the Marcell, he had advertised the sale of his home’s furnishings, including suites from the living room, dining room, and two bedrooms, along with curtains, draperies, oriental rugs, flatware, and tableware.

Presumably the sale was meant to raise funds for his next project, the Café Montmartre which he opened in January of 1923 on Hollywood Boulevard, with a coffee shop below it on street level. At the luxurious Café Montmartre he continued the method of luring customers that had been adopted at the Sunset Inn: linking the café to the movies, attracting stars and a gaping public. Reputedly this often involved subsidizing meals for actors short on funds. [photo: Los Angeles Public Library]

The Montmartre would become the restaurant most closely identified with him, and the longest lasting of his cafes, staying in business for nine years. He took an active role in it, greeting and mingling with guests from the film industry, as well as overall management. Yet that workload barely slowed him down. In May of 1923, the Los Angeles Examiner announced that Eddie, “Little Napoleon of the Cafes,” was planning to open “the exclusive Piccadilly Coffee House on West Seventh street between Hill and Broadway.”

1925 was a busy year of ups and downs. The Crillon closed, as did his newly opened cafeteria called Dreamland, not even open for a full year. It was the only cafeteria I’ve ever come across that had dancing!

He also began a catering company that furnished food to movie casts and crews. In the next few years, the catering company took on some big projects. In one case it provided meals for 2,500 in Yuma AZ when the Famous Players-Lasky studio was filming Beau Geste. [above photo] To do that it was necessary to build a plank road atop the sand and to drill wells. The company also catered to studios when they filmed in Hollywood at night, as was the custom. That could mean serving as many as 25 studios on some nights.

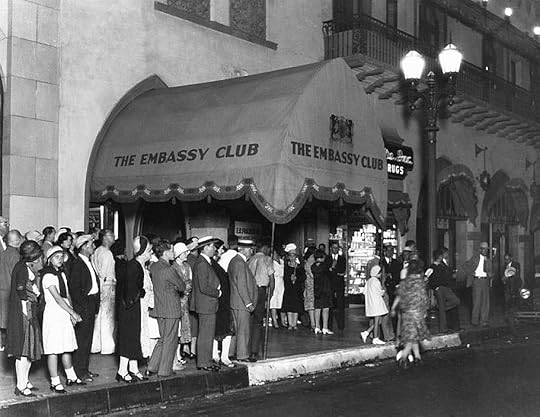

The Depression – and probably the end of silent film — took a toll. When Montmartre began to sag, he opened a swanky club next door for film people called the Embassy. It opened in 1929, closing three years later when his decision to open to the public failed to rescue it. [above: the public waits to get in] Also, in 1932 he was caught removing art objects and furnishings from the then-closed Montmartre, planning to use them in his next venture. At his trial it came out that the actual owner of the Montmartre was the realtor who had built the Montmartre and backed him by putting up capital, loaning him personal funds, and paying him a salary of $100 a week. He was found guilty and put on probation for two years.

In 1933 he opened a restaurant he called Sardi’s but in no way connected to New York’s Sardi’s. With booths, tables, and fountain service, and featuring his popular set-price buffet luncheon, it quickly became a success. Its success did not stop him, however, from launching another restaurant, a chop house called Lindy’s that he seemed to have no further link to. In 1936 Sardi’s was destroyed by fire. When it was rebuilt two years later he sold his share to a partner. [rebuilt Sardi’s shown above]

In 1939 he opened his final eating place, the Bohemia Grill, with prices as low as 35c for Pot Roast and Potato Pancakes. The following year he took his own life, apparently troubled by money worries. Among the honorary pall bearers at his funeral were Charlie Chaplin, Tom Mix, Bing Crosby, and studio head Jack Warner.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

October 27, 2024

An early health food empire

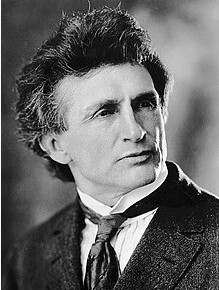

It’s rare to find business documents from long-gone restaurants, but last weekend I stumbled upon two letters to investors from the Physical Culture Restaurant Company headed by fitness and health food advocate Bernarr Macfadden [shown above, age 42].

Macfadden was a body-builder, natural food proponent, and entrepreneur who decided to spread the gospel by opening inexpensive, largely plant-based restaurants at the turn of the last century. He attributed his strength and energy to this special diet.

The 1904 end-of-year letter reported that four new restaurants had been added to the ten already in business, and that they had done business totaling over $243,000, with a net gain of $2,637. Five restaurants had been judged failures and closed, four of them in NYC and one in Jersey City. He and his board of directors believed in rapidly shutting down locations that did not draw crowds. The letter blamed a “business depression” and the normally slow start of new locations for the smaller-than-hoped-for profits.

Although he wanted the restaurants to succeed, his personal income was not dependent upon them. Macfadden’s primary business was publishing periodicals, beginning in 1899 with Physical Culture, which discussed diet and health, followed by True Story, Liberty and then, increasingly, a large number of detective and romance magazines with titles such as Dream World, True Ghost Stories, and Photoplay. In addition he authored scores of books on fitness, sex, and health, and established a tabloid newspaper, The New York Evening Graphic. His publications earned him a fortune.

The total number of Macfadden restaurants open at the same time never seemed to exceed sixteen or so. The first ones were in New York City, of which there were nine at one point. Others were spread across the East and Midwest, including Boston, Newark, Jersey City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. There was also one in Toronto. [above: 1906 advertisement and 1906 restaurant at 106 E. 23rd, NYC]

In the 1907 letter to stockholders shown above he floated the idea that the restaurant holdings might grow to 40 or 50 units if stockholders invested in more stock. This never happened.

Despite the growing popularity of the restaurants, it seems that for Macfadden they served primarily as a way to spread the gospel of a healthful diet. He could not be described as a restaurateur. No doubt he helped to conceptualize the restaurants and make up the early menus, but he did not manage them except in his role as corporate executive.

Prices were low in his early restaurants. A bowl of thick pea soup was 1c, as was a bowl of steamed hominy or oats or barley. Whole wheat bread and butter, however, cost 5c as did creamed beans or whole wheat date pudding. He sold loaves of whole wheat bread for 10c. [shown above]

A Macfadden menu shown in a 1919 British book reveals a wealth of choices then but also higher prices that reflect post WWI inflation. Five cents now bought less. Mushrooms on Toast cost 20c, as did meat substitutes Nuttose and Protose. A Macaroni Cutlet or Lentil Croquettes cost 25c, while omelets such as Mushroom, Walnut and Pecan, Orange, or Protose and Jelly were 30c.

In 1931, at which point only three Physical Culture restaurants remained, Macfadden gave up his fortune, said to be $5,000,000, and created the Bernarr Macfadden Foundation. In a radio broadcast he said: “It is a source of indescribable relief to feel like a free man again. Too much money unwisely used makes people greedy and ungrateful, destroys the home, steals your happiness, enslaves, enthralls you, lowers your vitality, and enfeebles your will.”

Yet his personal life continued to be full of numerous wives, affairs, and lawsuits. And, despite being “freed” of his fortune in 1931, he continued to spend money lavishly, taking it from the treasury of the Physical Culture Publishing Company after he turned that into a public corporation. Stockholders accused him of using nearly a million dollars for his own private interests, which included failed attempts to become a presidential candidate, governor of Florida, or mayor of New York.

In 1931 the Foundation opened the first of several Depression-era penny restaurants, no doubt modeled on Macfadden’s first restaurant at the beginning of the century where most dishes cost only one or a few cents. The initial Depression “pennyteria,” run by the Foundation, was located in midtown NYC. Drawing a crowd of about 6,000 a day, it quickly became self-supporting.

At a penny restaurant run by the Foundation, one cent would buy any of the following: coffee, split pea soup, navy bean soup, lentil soup, green pea soup, creamed cod fish on toast, raisin coffee, honey milk tea, cabbage and carrot salad, steamed cracked wheat, hominy grits, raisins and prunes, bread pudding, whole wheat doughnuts, whole wheat bread, or whole wheat raisin bread.

As the operator of the 1930s restaurants, the Foundation proved more flexible than Macfadden about dietary standards, but evidently he still had some say over what was served. According to one account he agreed to let meat appear on the menu as well as dairy products. Meat took the form of beef cakes, beef stew, and chicken fricassee. But he stood firm about bread, insisting only whole wheat be served.

I found no trace of the Macfadden restaurants nor the Foundation’s penny restaurants in the 1940s. Macfadden largely faded from the headlines, dying in 1955 and leaving an estate valued at only $5,000.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

October 13, 2024

Sell by smell

Through much of U.S. restaurant history, smells were a problem. Partly this was because of a lack of ventilation that caused the build up of odors of all kinds blended together in a miasma. Then there was also the ideal of the smell-free middle-class dining room where even delicious kitchen aromas were frowned upon. All this kept numbers of people out of restaurants.

Eventually this began to change. Better ventilation was achieved and restaurants learned to use good smells to their advantage, even as a kind of advertising. Today a restaurant owner might even hire an aroma consultant so that they may begin “profiting from pungency”!

Clearly that was exactly what a small Wisconsin drive-in did when the owners developed the “pizza-burger” following the end of World War II. Of course they didn’t hire a consultant, but their new type of hamburger was deliciously smelly in a way that attracted customers.

The sandwich was launched sometime around 1951 by veterans who had returned from the war, got a VA loan and opened a small roadside stand in Muskego WI selling burgers, hot dogs, and frozen custard. Soon it became a drive-in named Big 3 from which the partners launched the pizza-burger. Served on a toasted bun, it was made of ground pork and beef, cheese, chopped onion, and pizza sauce, the latter being the special, secret ingredient.

By 1956 franchises had been sold in every state in the U.S. As with Colonel Sanders’ fried chicken and “Chicken in the Rough,” franchisees bought the right to advertise with the product’s logo – the boy with the freaky nose – and a guarantee that the company would not license competing sellers within a delineated territory. It was not long before the inventors found food producers who bought rights to sell the pizza sauce and the frozen patties, greatly simplifying production for drive-in operators. [above: 1956 advertisement, Washington PA — note “Not a Gimmick”]

Despite the licensing, however, I have no doubt that many eating places around the country that claimed to offer pizza-burgers were not authorized and used their own guesswork recipes. One that I saw incorporated black olives.

The basic sandwich was so popular with teens that a similar one was soon adopted by school cafeterias, although recipes may have varied – greatly. For example, one I found used ground bologna and beef, and substituted spaghetti sauce for the carefully spiced pizza sauce.

The Muskego drive-in, later turned into a full-scale restaurant, is gone. But as of 2004 when the founder’s son was interviewed there were still a couple of places producing pizza-burgers under franchise.

Remarkably, the pizza-burger has been memorialized with a roadside marker.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

September 23, 2024

Postscript: Don the Beachcomber

A new book has come out about Don ‘s wife, Sunny Sund, who took over the Beachcomber chain and made it a success. Its author is Sunny’s daughter Karen, working with Cindi Neisinger. It is largely a personal account filled with anecdotes, a view of a mother/daughter relationship, celebrity mentions, and some of the harsh realities that shaped Sunny’s life. A drink recipe ends each chapter.

September 20, 2024

Free birthday cake!

A trip to Maine to celebrate two birthdays (not mine) got me thinking about how restaurants observe these events with customers. [above: at Wolfie’s, Miami, 1986]

The custom of restaurants recognizing birthdays with songs, cakes, fancy drinks, free dinners, and serenades took hold in the 1960s. It’s unclear whether it had anything to do with an IRS decision ca. 1959 not to charge a cabaret tax in eating places where servers sang birthday greetings.

But there was a notable earlier cake bestower: cafeteria king Clifford Clinton of Clifton’s fame. By 1945 he claimed to have given away over 110,000 birthday cakes to patrons. Of course since his restaurant was a cafeteria, it’s likely that there were no singing waiters involved.

Apart from the IRS, another barrier to growth of the custom was the royalties levied by a copyright holder who claimed rights to the Happy Birthday song until 2015. It led many restaurants to write their own birthday songs, particularly if they were large chains that would have been most likely to be caught. Otherwise, it seems that in independent restaurants waiters and waitresses sang the familiar, homey version pretty much fearlessly.

Songs aside, the special attraction that actually brought celebrants to a restaurant for their birthday was probably the freebies. There were numbers of people who wanted a free meal, dessert, or drink but didn’t really like being in the spotlight.

Despite all the deals, generous or skimpy, some diners rejected the whole idea of a public celebration of birthdays in restaurants. In his Chicago Sun-Times column, Roger Simon advised, “Never eat in a restaurant where the waiters sing ‘Happy Birthday.’” He echoed the spirit of the author of the “Lonely Man’s Doggy Bag Diary” who wrote in the Oakland Tribune that along with lobster bibs, wooden menus, flames, mushrooms, anchovies, patés, and so much more, he disliked “waitresses singing Happy Birthday to everyone.” The T.G.I. Friday’s chain eventually dropped the custom, sensing that many customers found it embarrassing.

Of course many restaurant owners found birthday (and anniversary) celebrations attractive as a way to draw customers. But it seems that deluxe restaurants were less likely to observe this custom, possibly judging that their guests weren’t looking for reduced prices or free desserts, preferred privacy, and didn’t find the drama of singing waiters appealing.

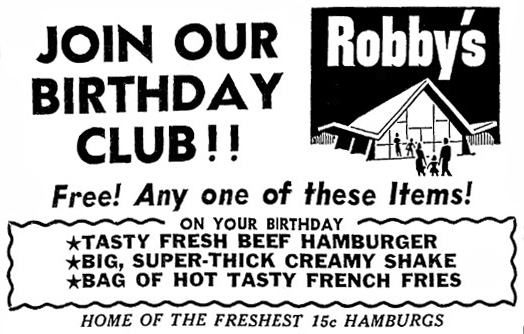

Restaurant chains, on the other hand, tended to make a big deal of their generosity toward birthday celebrants. As the growing popularity of television kept families home and reduced restaurant visits in the 1950s and later, a restaurant management advisor suggested “. . . one possible way to help offset the decline in business might be to get more people to celebrate birthdays by going out to dinner.” Many restaurants created birthday clubs.

Often customers seeking birthday specials were required to fill out forms prior to their birthdays, and to notify the restaurant when they were planning a visit. And, quite a few restaurants required that would-be celebrants bring along their birth certificates, suggesting there were customers who lied about their birthday.

Some customers evidently had a much harder time convincing restaurants that it was really their birthday. As late as 1991, a 13-year old Black girl in Vallejo CA was refused her free birthday meal at a Denny’s restaurant even though she brought her baptismal certificate. She told a reporter that “They just said that wasn’t enough and made a big scene. I felt embarrassed. It was humiliating because other families in there were looking at us, and I guess they thought we were some kind of bad criminals.” Her case became part of a successful class action suit brought against Denny’s in California.

There were some restaurants that developed more elaborate rules concerning the precise kind of “deals” they were offering and who was eligible. The Bill Knapp’s restaurants offered free birthday cake, not just for the guest celebrating their birthday, but for the entire party. The main guest also benefited from a 1% reduction in the price of their meal for each year of age over 11. Another Michigan restaurant, Dennison’s in Farmington Hills, offered cake plus a discount on the celebrant’s meal based on the size of the party. Benihana in New Orleans served a free dinner valued at upwards of $14 to the birthday guest in the early 1980s, but only if there were four in the party.

Cake wasn’t the only kind of birthday food offering. Brennan’s in New Orleans presented French bread decorated with cherries, olives and lemon slices. The bread was not meant to be eaten, just to hold a candle. Accompanying it was a character made of fruit and vegetables, followed by an Irish coffee. Cocktails took the place of dessert in some restaurants. At the Asian restaurant Jade East in New Orleans a celebrating guest received a flaming pousse-café with layers of blue Curaçao, grenadine, and rum or gin.

I’m not expecting any free cake or singing waiters/waitresses in restaurants we’ll visit this weekend — but if I’m wrong I’ll report back.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

September 8, 2024

Beer & barbecue at the fair

The 19th century was the century of world’s fairs, but the United States did not have a fair to call its own until 1876 when Philadelphia celebrated the 100th anniversary of U.S. independence. After Philadelphia, Chicago’s, in 1893, was the largest in this country. [above, outdoor beer garden at the Tyrolean Alps]

So . . . for St. Louis organizers of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, when St. Louis was the fourth largest American city, second-largest Chicago figured as the one to beat. St. Louis fair organizers hoped to surpass the Chicago fair in all ways, particularly attendance.

The St. Louis fairgrounds occupied an immense 1,200 acres, double the area of Chicago’s. Not only was the area very large but so were the buildings. A hotel on the fairgrounds, the Inside Inn, had 2,357 rooms and dining rooms accommodating 2,500 at a time. The Palace of Agriculture building alone covered 23 acres. Big money too: the entire outlay for the city, U.S. government, participating nations and states, exhibitors, and concessionaires came to over $500M in today’s dollars.

Planning the fair’s restaurants, with enough variety in fare and price to please fairgoers, was a formidable task. In St. Louis, those interested in being considered included owners of existing city restaurants, experienced professionals who made a career of running restaurants at fairs, various exhibitors who wanted to include a themed restaurant as an added attraction, some state and foreign nation buildings and exhibits, and food and drink companies and promoters.

The offerings ranged from about 50 stands selling sandwiches to 75 full-scale restaurants, some of them expensive. There were also oddities such as a proposed underground eating spot in the Anthracite Mining exhibit’s coal mine with waiters dressed as miners. Or, the restaurant in Hereafter — a tour through Dante’s Inferno — where diners ate off coffins in the Café of the Dead, probably an imitation of the Café of Death in Paris’ Montmartre.

Without a doubt the most lavish, expensive, huge, and overall outstanding restaurant was the Tyrolean Alps, organized by two prominent restaurateurs, New York’s August Luchow and St. Louis’ Tony Faust, plus three other experienced St. Louis caterers, and with many backers including St. Louis brewer Adolphus Busch. Like several others it could handle an estimated 2,500 diners at a time. Despite all the banquets it catered, the famous people who dined there, its extensive menu, its general popularity, and its gross receipts of nearly $1M, like so many concessions it managed to lose money by fair’s end. It carried on for a time post-fair, into the summer of 1905.

Even before the fair ended some restaurant concessions had failed. The two owners of the Japanese restaurants [shown above], overcome with debt, filed for bankruptcy. The German Wine restaurant that charged $2 for a lunch with wine, proved to be far too expensive for fairgoers. Also, beer, not wine, was the preferred beverage at the fair, costing a nickel for a glass or a dime for a stein. Beer pavilions, such as Falstaff’s and Blatz’s, competed with the almighty Budweiser, widely available and practically the official beer of at least 17 of the restaurants.

I haven’t found reports on how well the food stands did, but I’m guessing they fared better than many of the full-scale restaurants. The Barbecue, with six stands spread around the fairgrounds, was quite popular with the crowds. A reporter from Wichita KS let her readers know that it was a good deal, not requiring much money or time in being served, whether ordering hot beef, pork, mutton or sausage sandwiches. Plus, she reported, they supplied free paper cups and spoons (!).

Another winner was the enormous Inside Inn, the only hotel on the fairgrounds and the biggest financial success of the fair. A ham sandwich was 10 cents, while a complete dinner was 75 cents, and breakfast and lunch each cost 50 cents. At fair’s end, the Inn showed a sizable profit.

There were about a half dozen women operating restaurants. Prominent among them was well-known cookbook author Sarah Tyson Rorer who had also been at the Chicago fair. She ran a large restaurant seating 1,200 prominently located in the East Pavilion building [shown above], and she taught cooking classes. Harriet McMurphy, a food reformer and domestic science lecturer from Omaha, ran an eating place designed for people with digestive difficulties. She had very definite ideas of what was best to eat, rejecting pastry as something that should not be eaten more than once a year. Instead she offered baked apples with almonds and whipped cream. A local woman, Mrs. Reid, operated a breezy tea room called The Bungalow designed for women guests.

A few of the women restaurant operators also did the catering for some of the many banquets given during the fair, possibly including wedding ceremonies held in Ferris wheel gondolas [visible above] accommodating 60 persons.

The St. Louis fair has often been criticized for its disrespectful treatment of Philippine tribal people brought there to demonstrate the U.S.’s beneficial domination of developing nations considered inferior. Evidently they adjusted to modernity very quickly, soon tiring of the rice diet they were fed at the fair and demanding an American diet such as found at the restaurants. They were granted their wish.

A lesser known scandal was how Black fairgoers were treated. In June, a group of Black visitors observed notices posted by restaurants on the Pike that read “No colored people served in this restaurant.” Then complaints were received that white servers were refusing to sell glasses of water to Black visitors, claiming that if they did they would lose their white customers. The fair organizers expressed dismay and there was discussion about hiring a Black woman who would run a stand to greet visitors of color, but that did not materialize and the number of Black visitors declined. The water issue was supposed to be “solved” with separate tanks of water and distinctively marked glasses. Unsurprisingly, the Black press denounced the fair. The Cleveland Gazette, for instance, advised “Our people had better stay away from the St. Louis World’s fair. There is much discrimination on the grounds.”

In the end, the St. Louis World’s Fair drew about 8 million fewer visitors than had Chicago’s exposition. The sideshow amusements lost so much money that the chairman of the Pike Financing Co. reported, “So universal has been the losing on the Pike that not one of the St. Louis shows will be taken to Portland,” the site of the next big fair. Despite all the losses for private investors who naively expected to make money, the fair’s Exposition Company managed to break even after paying back government loans.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

August 18, 2024

Summertime restaurant-ing

Here are some of my blog posts from the past that were about visiting restaurants when it’s hot outside.

See also “Dining in a garden.”

Americans living in cities enjoyed spending hours in tea gardens in the 18th century and beer gardens in the 19th and early 20th. One example of such a pleasure garden was a grassy Philadelphia spot outfitted with “tables, benches, boxes, bowers, etc. and delightfully shaded by fruit trees.” However, eating outside near a road was disagreeable and largely unheard of. This began to change around the start of the 20th century — but even then only in a small way, except maybe in New Orleans where sidewalk cafes were said to be common.

Ice cream has a long history as a commercial product in this country. For decades it was not sold packaged in stores but was mainly consumed in public settings, often in park-like pleasure gardens. By the 1860s, though, Bostonians could enjoy their ice cream at Brigham & Son’s Ice Cream Saloon which also furnished a variety of other sweet treats such as Charlotte Russe and Jelly Whips. By the 1920s, as car ownership increased, roadside chains selling ice cream began to appear, including of course, Howard Johnson’s.

Summer was a slow season for eating places even into the early 20th century. Small marginal cafes, of which there were many, could not always afford to install large fans, assuming they even had electricity. Another alternative, at least for restaurants higher in the pecking order, was to close up their city location and run another place in a summer resort. Needless to say the adoption of air conditioning around WWII was a life saver for restaurants and they were quick to announce it in their advertising.

Rooftop drinking and dancing became popular in New York City in the 1890s. Over time these spots added dinners. They were especially likely to be atop hotels. Soon their popularity spread across the country. Clearly the attraction was about avoiding summertime heat, so it is not surprising that they tended to disappear as the 20th century found new ways to keep people cool.