Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 34

May 11, 2014

Famous in its day, now infamous: Coon Chicken Inn

The long-gone Coon Chicken Inn restaurant chain claimed in its advertising that it was “nationally famous.” I believe that was a bit of an exaggeration – then – but it might be true now. Its present-day fame, more accurately its notoriety, is based on its objectionable name and use of a grotesque racist image on buildings, delivery trucks, china, glassware, and printed advertising pieces.

To whatever degree it was nationally famous it can only have been for its racist depictions. Certainly it could not have achieved fame for its food. The menu of the Coon Chicken Inn reveals selections only a few degrees more ambitious than the drive-ins of the 1930s. Other than chicken dinners, the menu included chili, burgers, and ice cream desserts.

Nonetheless, in its time it was a popular chain of four roadhouse restaurants with one each in Salt Lake City (est. 1925), Seattle WA (est. 1929), Portland OR (est. 1930), and Spokane WA. According to one account there were also Coon Chicken Inns in Denver, Los Angeles, and San Francisco but I’ve been unable to find any trace of them.

In 1930 Seattle’s NAACP protested against the restaurant’s racist imagery. Under threat of prosecution the chain’s owners, Maxon Lester Graham and Adelaide Graham, repainted the grotesque black faces on their restaurants’ entryways blue. They also obliterated the words “Coon Chicken Inn” painted on the figures’ teeth.

Having avoided prosecution they changed nothing else, keeping the chain’s name and logo, all of which seemed not to bother the restaurants’ white patrons at all. I would guess most people gave little thought to the large grinning heads, having already accepted the caricatures as merely another instance of the widespread “comical” portrayal of black Americans. They probably also saw them as just another example of an eye-catching building feature employed by roadside restaurants to attract motorists’ attention. Few white people perceived the restaurants as racist.

Having avoided prosecution they changed nothing else, keeping the chain’s name and logo, all of which seemed not to bother the restaurants’ white patrons at all. I would guess most people gave little thought to the large grinning heads, having already accepted the caricatures as merely another instance of the widespread “comical” portrayal of black Americans. They probably also saw them as just another example of an eye-catching building feature employed by roadside restaurants to attract motorists’ attention. Few white people perceived the restaurants as racist.

The Coon Chicken Inns regularly hosted meetings of clubs, civic organizations, and sororities ranging from a Democratic Club to the Junior Hadassah. They were the sites of wedding, anniversary, and birthday parties. In 1942 they were listed in Best Places to Eat, a nationwide guidebook published by the Illinois Auto Club. I can’t help but think that the restaurant in Portland was a peculiarly appropriate location for an Eastern Star group that chose it for their “Poor Taste” party in 1937.

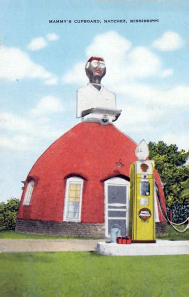

Like the word “mammy” and its stereotyped image, “coon chicken” was supposed to communicate that the restaurant specialized in Southern cuisine, in this case fried chicken. Mammy names and images were widely used by restaurants in the early and middle 20th century. The crudely constructed Mammy’s Cupboard in Natchez MS was another example of roadside “building as sign.” There was a Mammy’s Shanty in Atlanta, Mammy’s Cafeterias in San Antonio TX, and others in the South. Nor was the East without its Mammys: in Atlantic City was Mammy’s Donut Waffle Shop while Brooklyn had Mammy’s Pantry.

Like the word “mammy” and its stereotyped image, “coon chicken” was supposed to communicate that the restaurant specialized in Southern cuisine, in this case fried chicken. Mammy names and images were widely used by restaurants in the early and middle 20th century. The crudely constructed Mammy’s Cupboard in Natchez MS was another example of roadside “building as sign.” There was a Mammy’s Shanty in Atlanta, Mammy’s Cafeterias in San Antonio TX, and others in the South. Nor was the East without its Mammys: in Atlantic City was Mammy’s Donut Waffle Shop while Brooklyn had Mammy’s Pantry.

Several good articles have been published analyzing the Coon Chicken Inn’s everyday racism and the white public’s blithe tolerance of it. I recommend Catherine Roth’s essay for the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. Because of the volume and quality of what’s been written I hesitated at first to publish this post. I also hate the thought of increasing the desirability of Coon Chicken Inn advertising artifacts. Although there are good reasons to preserve historic racist ephemera, the extreme popularity of these images is disturbing. So great is the demand for them that the marketplace is flooded with fakes, including newly dreamed-up objects that were never used by the chain. Black faces have made a comeback along with “Coon Chicken Inn” on the teeth.

The Portland and Seattle branches of the Coon Chicken Inn closed in 1949 but the Salt Lake City unit remained in business until 1957.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

May 4, 2014

Nothing but the best, 19th cen.

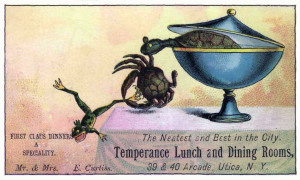

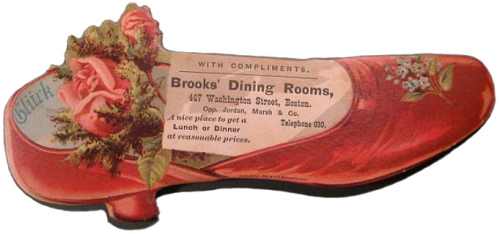

Restaurant advertising in newspapers of the 19th century tended to be very wordy, often using conventional phrasing such as “best the market provides” and “available on the shortest notice.” Once in a while a stereotyped line drawing of oysters would appear in an advertisement but usually they were all text. (This post is illustrated with business cards of the kind that came into use in the 1870s and 1880s.)

Restaurant advertising in newspapers of the 19th century tended to be very wordy, often using conventional phrasing such as “best the market provides” and “available on the shortest notice.” Once in a while a stereotyped line drawing of oysters would appear in an advertisement but usually they were all text. (This post is illustrated with business cards of the kind that came into use in the 1870s and 1880s.)

What follow are examples of advertisements that depart from convention and give a glimpse of the sometimes humorous claims and boasts of their times.

Epicurean Wit, 1803

“In choosing an appellation for his Hotel, he has endeavored to attract the notice of gentlemen of elegant leisure, or of delicate health; and he trusts he shall, in pursuance of his Motto [“Tam Epicuro, Quam Momo”] be enabled to combine in his social retreat, all the invitations which the politest palate may require, with all the wit-inspiring ingredients of intellectual festivity.”

– Othello Pollard’s Hotel, Cambridge MA

Indulge Yourself, 1815

“Persons inclined to indulge in the height of European luxury may be accommodated to their wishes. Chicken, Eel, and Game Pies; Puff Pastry, in variety; sweet and savory Jellies; plain and ornamented Omelettes; Creams; Blancmanges; almond, caramel, and gum Paste Ornaments; Italian Sallads; potted and collard Meats; Fish Sauces; cold ornamented Hams, Tongues, Fowls, and savory Cakes.”

– Mrs. Poppleton, Restaurateur, Pastry Cook, and Confectioner, NYC

No Ruffians, 1820

No Ruffians, 1820

“John Sherlock … respectfully acquaints epicures and connoisseurs that he is constantly receiving a fresh supply of that palatable, salutary and invigorating diet – Oysters, at his residence Washington Street opposite the Union Tavern … where he hopes to receive the resident citizens of this part of the District, or strangers; assuring them, that not only the quality of the Oysters will be attended to, but the cleanliness and neatness of the entertainment – no unpleasant company being admitted to his house.”

– Sherlock’s Oyster House, District of Columbia

Best of Both Worlds, 1822

“Being an entire stranger in Boston, though well known to individuals to whom he can refer, he may have occasion for some indulgence and allowances in little matters, until he can become perfectly acquainted with the local and prevailing taste – But no pains will be spared to gratify all – and to reconcile the fantaisies de Paris with the Boston notions …”

– Bertrand LaTouche’s Restaurateur, Boston

New Murals, 1843

New Murals, 1843

“While his palate is being tickled with a nice piece of delicious salmon, [the diner] may jump off Passaic Falls with Sam Patch, and while his eye gloats upon the juicy quarter of a savory canvas back, he may indulge in a promenade through Broadway, and as he discusses the merits of a cup of coffee, he may stand like Asmodeus upon the summit of the highest shot tower of the Monumental city. It is really a rich arrangement and worth double the price of a dinner to take a peep at it.”

– Ford’s Restaurant, Boston

As Good as Any, 1847

“His motto is ‘Let Brooklyn take care of itself!’ Why go to New York to dine? His table is every day furnished with the same delicacies of equal quality to any in New York, no matter how high the standing of the establishment.”

– Bell’s Refreshment Saloon, Brooklyn

Nick Nacks, 1850

“All the Nick Nacks of the Season, Green Turtle Soup Three Times a Week, Callapee and Calapash, West India fashion.”

– Pic Nic Saloon at the Bowery Reading Room, NYC

Best People, 1852

“Here meet daily the wits, fast men, and bloods of the town, to whose enjoyment it is his pleasure to cater. A Free Lunch is served daily, and every evening may be obtained a Supper, for which is expressly prepared all the delicacies of the season.”

– Charley Abel’s, NYC

A Treat, 1856

A Treat, 1856

“The Dinner at Winn’s, oh my! Another of the Same Sort before I die! Husbands take their Wives, Lovers their Sweethearts, and Old Bachelors themselves, to Winn’s for a Good Breakfast, Dinner or Supper.”

– Winn’s Fountain Head, San Francisco

“Pro-Bono Publico,” 1861

When Fainting with Hunger, how pleasant to meet

With a friend who’ll provide us with something to eat;

Refreshed, with new zeal we life’s journey pursue,

As thousands attest who their meals take of – TRUE.

– Lewis P. True’s Montgomery Dining Saloon, Boston

No Horsemeat, 1869

“One of the most Central, clean and best kept establishments of this sort in the State of Michigan, is the ‘Metropolitan,’ under the First National Bank. It has two heads, (which are better than one, we don’t say which,) and they belong to the brothers HODGE. Bon vivants, get an appetite and give Hodge Brothers a chance to get you up a lunch. They won’t ask you to ‘eat a horse.’ You bet.”

– Metropolitan Restaurant, Bay City, Michigan

Unusual Fare, 1869

Unusual Fare, 1869

This café has now become one of the popular institutions of the city. A new Turkish drink, called ‘Salepp,’ will be sold. This is a novelty in this country, and is made from a root grown in Asia Minor. It both healthful and pleasant to the taste. The only pure Mocha coffee in the city is sold here.”

– The Turkish Restaurant, Chicago

Natural Attractions, 1871

“Among the many attractions in Liberty is a natural one in the way of a pair of large Gold Fish, which attracts the attention of many, to look at them. All are invited to step in and look at them. The Subscriber has converted his Ice Cream Saloon into a first class Restaurant and Oyster Room where he will serve up Oysters in many ways, and guarantees satisfaction in every thing sold by him.”

– Pierson’s Restaurant, Liberty, Missouri

Clean and Neat, 1872

“It would take a microscope inspection to discover a spot on any of his immaculate linen. All about the little house, from the quaint French pictures, to the bright and burnished cooking range, is as neat as a pin. All Peter wants is a trial. His motto is Excelsior! And all other caterers must look to their laurels, or he will be perforce the ‘king of the roost.’”

– Peter Loiselles, Galveston, Texas

Don’t Sneer, 1873

Don’t Sneer, 1873

“Hi You Muck-A-Muck And Here’s Your Bill of Fare: Three Kinds of Meat for Dinner; Also for Breakfast and Supper. Ham and Eggs every day, and Fresh Fish, Hot Rolls and Cake in abundance. Plenty of Tea and Coffee every day for Dinner and Hiyou Sike’s Ale on Sunday. Hurry up, and none of your sneering at Cheap Boarding Houses. Now’s the time to get the wrinkles taken our of your bellies, after the hard winter.”

– Thompson’s Two-Bit House, Portland, Oregon

Boston’s Taste, 1884

“After fifteen years of laborious study, Mr. Louis P. Ober believes he has found the pulse of the public taste of Boston. He responds to the long-felt want of a salon where gentlemen will feel at home.”

– Ober’s Restaurant Parisien, Boston

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

April 27, 2014

Revolving restaurants II: the Merry-Go-Round

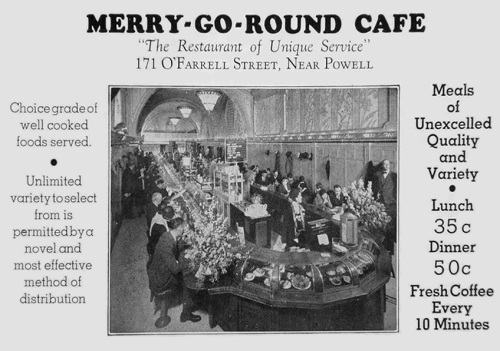

Apart from amusement parks, I think of merry-go-rounds mostly in conjunction with bars. It seems they served as jolly imbibing venues in the 1930s after Prohibition ended. It makes me mildly queasy to think of them going round and round but presumably they revolved very slowly and presented no hazards to tipsy customers. [pictured below is San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel bar during WWII]

Apart from amusement parks, I think of merry-go-rounds mostly in conjunction with bars. It seems they served as jolly imbibing venues in the 1930s after Prohibition ended. It makes me mildly queasy to think of them going round and round but presumably they revolved very slowly and presented no hazards to tipsy customers. [pictured below is San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel bar during WWII]

Even before revolving bars came upon the scene restaurateurs were dreaming up various sorts of revolving restaurants. I’ve written before about restaurants atop tall buildings that let diners gaze upon ever-changing vistas spread out before them. California also had counter-style restaurants made with a revolving inner counter that held food in glass-enclosed compartments, almost like a revolving Automat, but without slots for coins. Some were round while others had a U-shape.

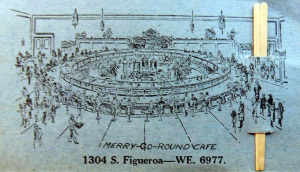

Gustav and Gertrude Kramm were likely the first to introduce the merry-go-round concept to diners. Around 1930 they established two Merry-Go-Round Cafes in Long Beach CA incorporated as Revolving Table Cafés, Ltd. The corporation also produced the revolving serving tables. In 1931 Gustav filed a patent application for a “Café Table of the Traveling Conveyor Type,” for which engineer Harold Hackett was listed as inventor. It involved two conveyors, the top loaded with prepared relishes, salads, sandwiches, and desserts, and the lower one transporting dirty dishes to the kitchen. The conveyor traveled slowly enough, and the selection of dishes was repeated often enough, that customers could lift the glass doors and remove food easily.

Gustav and Gertrude Kramm were likely the first to introduce the merry-go-round concept to diners. Around 1930 they established two Merry-Go-Round Cafes in Long Beach CA incorporated as Revolving Table Cafés, Ltd. The corporation also produced the revolving serving tables. In 1931 Gustav filed a patent application for a “Café Table of the Traveling Conveyor Type,” for which engineer Harold Hackett was listed as inventor. It involved two conveyors, the top loaded with prepared relishes, salads, sandwiches, and desserts, and the lower one transporting dirty dishes to the kitchen. The conveyor traveled slowly enough, and the selection of dishes was repeated often enough, that customers could lift the glass doors and remove food easily.

Hot food, particularly main dishes, soup, and coffee, was delivered by servers who worked behind the counter.

Hot food, particularly main dishes, soup, and coffee, was delivered by servers who worked behind the counter.

Essentially the conveyor system was implemented so that the maximum number of customers could be served a fairly wide range of food inexpensively in a limited amount of space. The specialty of the Merry-Go-Rounds was the provision of full meals averaging 35 to 50 cents, an attractive bargain during the Depression. For 50 cents diners could order a main dish such as Ham Steak with Country Gravy and then choose two salads and two desserts from the revolving counter, along with all the relishes, rolls & butter, and coffee they wanted.

The Kramms operated some of the Merry-Go-Rounds and leased others. By the end of 1930 there were units in Long Beach (2), Los Angeles (4), and Seattle WA (1). Later Merry-Go-Rounds were opened in Huntington Park, Pasadena, San Diego, San Francisco, and possibly Santa Barbara, California. I’m not sure how long the restaurants remained in business but I could find no trace of them beyond 1941.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

April 20, 2014

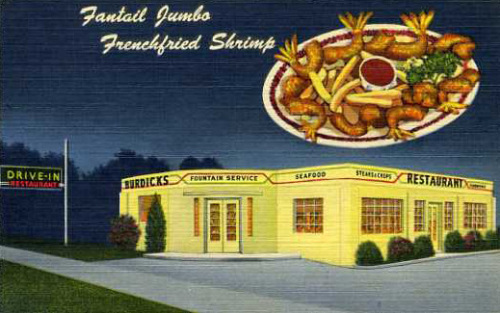

Basic fare: shrimp

Recently I heard that a shortage of shrimp due to disease is causing prices to shoot up. I stopped to wonder how long shrimp had been on American restaurant menus. I could find no instances before the Civil War.

Recently I heard that a shortage of shrimp due to disease is causing prices to shoot up. I stopped to wonder how long shrimp had been on American restaurant menus. I could find no instances before the Civil War.

Americans have probably been eating shrimp at home for centuries but shrimp didn’t make a splash in American cookbooks until after the Civil War when they became available in cans. Shrimp salad, usually whole shrimp piled up on lettuce with a mayonnaise dressing, became something of a delicacy that was especially popular with women. It began to show up on hotel menus as well.

Shrimp cocktail, not really so different than shrimp salad, became a staple of banquets in the early 20th century. Instead of mayonnaise a cocktail sauce was used; it was similar or the same as oyster sauce and based on catsup with ingredients such as lemon or vinegar, tabasco or Worcestershire sauce, and horseradish added to give it zing.

Shrimp cocktail, not really so different than shrimp salad, became a staple of banquets in the early 20th century. Instead of mayonnaise a cocktail sauce was used; it was similar or the same as oyster sauce and based on catsup with ingredients such as lemon or vinegar, tabasco or Worcestershire sauce, and horseradish added to give it zing.

Fried shrimp seems to have become a menu item in the early 20th century also, but breaded, deep fried shrimp did not make its big debut until after World War II when pre-cooked frozen shrimp, plain or breaded, came on the market. Then shrimp dinners, relatively cheap because the breading could cover less desirable specimens, became available everywhere, even in many drive-ins.

Until the advent of frozen shrimp, shrimp cocktail and fried shrimp were found most often on menus of restaurants in the Gulf states and California. In the late 19th and early 20th century locally caught shrimp were so plentiful in San Francisco that it was the custom for restaurants to present diners with a free plate of shrimp to nibble on before their meal was delivered.

Importation of shrimp from Mexico and India began in the early 1950s, but evidently it took some time before prices went down. Shrimp cocktail remained a minor luxury for many people through the 1960s. The cost of shrimp was high enough in the mid-1950s to make the theft of frozen shrimp a serious issue for New York’s Mamma Leone’s, which lost thousands of dollars worth of $1.12/lb shrimp to a ring of thieves. The thieves turned out to be a pantry man colluding with garbage collectors who resold the shrimp to other restaurants.

In today’s dollars Mamma Leone’s shrimp cost close to $10/lb, but in actuality prices are much lower than that now due to shrimp farms in Asia and Ecuador that supply most of what Americans eat in restaurants.

One last note, on the distinction among shrimp, scampi, and prawns. This could launch a long discussion about how many species of shrimp there are, what they are called in various parts of the world, etc. But for all practical purposes, in standard menu-ese scampi, often given as “shrimp scampi” on menus, refers to shrimp cooked in butter and garlic and prawns are very large or “jumbo” shrimp. Sometimes the terms are bizarrely combined on menus. The finest example of this I’ve seen was a 1977 Richmond VA menu partially shown above. For an International Seafood Festival it offered an Italian special called Scampi Portofino which was described as “Jumbo Shrimp Prawns.” I guess those were really, really big shrimp-style shrimp.

One last note, on the distinction among shrimp, scampi, and prawns. This could launch a long discussion about how many species of shrimp there are, what they are called in various parts of the world, etc. But for all practical purposes, in standard menu-ese scampi, often given as “shrimp scampi” on menus, refers to shrimp cooked in butter and garlic and prawns are very large or “jumbo” shrimp. Sometimes the terms are bizarrely combined on menus. The finest example of this I’ve seen was a 1977 Richmond VA menu partially shown above. For an International Seafood Festival it offered an Italian special called Scampi Portofino which was described as “Jumbo Shrimp Prawns.” I guess those were really, really big shrimp-style shrimp.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

April 13, 2014

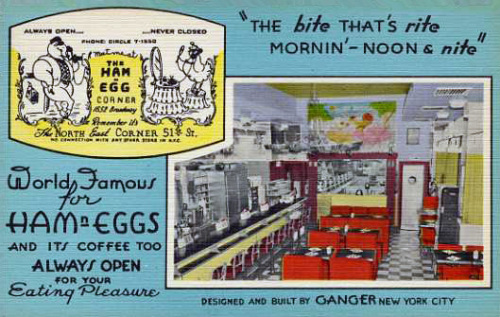

We never close

One way of sorting eating places is by the hours they keep. Those that are open 24 hours a day stand out from the crowd by their tirelessness and involvement in sometimes unwanted adventures.

One way of sorting eating places is by the hours they keep. Those that are open 24 hours a day stand out from the crowd by their tirelessness and involvement in sometimes unwanted adventures.

Mostly there are three kinds of customers for all-night restaurants: those who travel at night, those who work at night, and those who play at night.

In pre-Civil War NYC all night eateries were haunts of “b’hoys,” a class of rogue males (sometimes accompanied by their g’hals) prominently made up of firemen and the more prosperous newsboys. They enjoyed oyster cellars, but one of their favorite places in the 1840s was Butter-cake Dick’s, where for a mere 6 cents they could get a generous plate of biscuits with butter and a cup of coffee.

The authors of the many Victorian “lights and shadows” books about urban immorality were quite fascinated by the dubious goings on in all-night supper clubs. No doubt their readers felt a shiver of horrified excitement when they spotted signs along city streets advising “Ladies’ dining parlor, up stairs”’ or “Refreshments at all hours.” Was it or wasn’t it?

The authors of the many Victorian “lights and shadows” books about urban immorality were quite fascinated by the dubious goings on in all-night supper clubs. No doubt their readers felt a shiver of horrified excitement when they spotted signs along city streets advising “Ladies’ dining parlor, up stairs”’ or “Refreshments at all hours.” Was it or wasn’t it?

One such book was George Ellington’s The Women of New York; Or, the Under-world of the Great City. But even Ellington observed that patrons of private dining rooms in these quasi-bordellos were also there to eat. He reported that patrons could be discovered consuming fish balls or pickled salmon at 3 or 4 a.m.

People working at night surely outnumbered the pleasure seekers. Thomas Edison recalled that when his machine shop was on Goerck Street in NYC in the 1880s he used to grab a bite at 2 or 3 a.m. at a rough little place: “It was the toughest kind of restaurant ever seen. For the clam chowder they used the same four clams during the whole season, and the average number of flies per pie was seven. This was by actual count.” No doubt many of his fellow diners included some outside the law but also other denizens of the night such as newspaper printers, trolley conductors, bakers, and factory shift workers.

All-night restaurants were not just found in NYC but in all big cities and were often densest in areas near newspapers, city food markets, and ferries. Chicago’s all-night cafes on State Street were often portrayed as unsavory places where police connected with “stool pigeons” enjoying their midnight snack. Upstanding citizens shrank from the mere thought of all-night eateries but in actuality they were probably some of the most democratic places in that they drew characters from all stations of life.

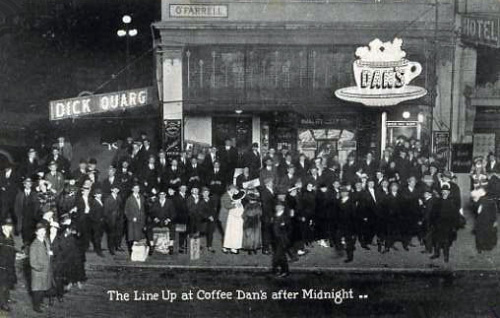

An all-nighter of renown in the 20th century was Coffee Dan’s, originally in San Francisco, which operated as an eating and entertainment venue, then a speakeasy in the 1920s and early 1930s. Its attitude in the mid-1920s is nicely expressed in the claim, “There will be dancing to the tinkle of a piano; there will be songs and it will never, never close, not even for fire, not even if the supply of ham and eggs is exhausted.” Coffee Dan’s expanded into a small chain and the Hollywood location became something of a gay hangout in the 1950s, a role played by all-night cafeterias such as Stewart’s in NYC’s Greenwich Village.

With so many night shifts for war workers in World War II, the demand for all-night restaurants rose to new heights. A 1948 restaurant sanitation manual noted how difficult it became to clean restaurants during wartime because of the never-ceasing 24-hour influx of customers.

The only figures I’ve run across concerning all-night restaurants were from the mid-1960s when 10% of eating places fell into that category. Some chain restaurants, especially coffee shops, pancake houses, and places offering breakfast at all hours, are founded on the 24-hour principle. Often they are located near highway exits to capture truck drivers and other nocturnal travelers.

The only figures I’ve run across concerning all-night restaurants were from the mid-1960s when 10% of eating places fell into that category. Some chain restaurants, especially coffee shops, pancake houses, and places offering breakfast at all hours, are founded on the 24-hour principle. Often they are located near highway exits to capture truck drivers and other nocturnal travelers.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

See also:

Toddle House

Cabarets and lobster palaces

April 6, 2014

Tablecloths’ checkered past

Throughout the 20th century red and white checked tablecloths in restaurants sent clear messages to patrons: this restaurant is inexpensive, friendly, and unpretentious. Whether ethnic or “American” they suggested that the customer was in a homey place, either authentically old fashioned or old world.

Throughout the 20th century red and white checked tablecloths in restaurants sent clear messages to patrons: this restaurant is inexpensive, friendly, and unpretentious. Whether ethnic or “American” they suggested that the customer was in a homey place, either authentically old fashioned or old world.

What kind of ethnic? Beyond noting that they were never Chinese (that I’ve discovered — so far), restaurants with checked tablecloths could be Italian or French, but also German, Viennese, Spanish, British, Greek, Hungarian, or Mexican.

As for signaling old-fashioned Americanness, that could mean “Pioneer Days on the Prairie,” “Frontier Saloon,” “Old-Time Beer Hall,” “Country Barn Dance,” “California Gold Rush,” “Grandma’s Kitchen,” “Colonial New England,” or “Gay Nineties.”

I use the past tense when referring to red and white checked tablecloths, not because they aren’t still around, but because I sense their vogue has ended, at least temporarily. I would say their appeal was strongest from the 1930s through the 1970s.

The fabric itself dates far back into the 19th century. Already by 1900 checked tablecloths were seen as old fashioned. But unlike other material culture of restaurant-ing, the meanings of the tablecloths were created as much by fundraising events and celebrations sponsored by churches, clubs, and schools as they were by restaurants.

The fabric itself dates far back into the 19th century. Already by 1900 checked tablecloths were seen as old fashioned. But unlike other material culture of restaurant-ing, the meanings of the tablecloths were created as much by fundraising events and celebrations sponsored by churches, clubs, and schools as they were by restaurants.

In restaurants, as well as outside them, the tablecloths have been accompanied by at least one of the following decorative touches: candles in wine bottles, lanterns, travel posters, braided garlic hung from walls, murals of villages, beamed ceilings, knotty pine paneling, wagon wheels, and peasant costumes. Candles in bottles were close to mandatory.

A number of famed restaurants used the tablecloths at some point in their history. A few of them fell outside the inexpensive class such as the “21″ Club [pictured] and the London Chop House. In 1961, a New York restaurant reviewer wrote that checked tablecloths were “almost obligatory for unpretentious Gallic restaurants in this city.” Boston’s Durgin-Park used them on their long communal tables, furnishing the means for burglars to tie up the staff during a 1950s robbery. In Chicago, the Drake Hotel’s Cape Cod Room added the colorful cloths to its busy decor that included pots and pans hanging from the ceiling.

A number of famed restaurants used the tablecloths at some point in their history. A few of them fell outside the inexpensive class such as the “21″ Club [pictured] and the London Chop House. In 1961, a New York restaurant reviewer wrote that checked tablecloths were “almost obligatory for unpretentious Gallic restaurants in this city.” Boston’s Durgin-Park used them on their long communal tables, furnishing the means for burglars to tie up the staff during a 1950s robbery. In Chicago, the Drake Hotel’s Cape Cod Room added the colorful cloths to its busy decor that included pots and pans hanging from the ceiling.

Surprisingly it wasn’t until the 1980s that anyone admitted they were tired of seeing the classic tablecloths in restaurants. The ascent of Italian restaurants into the higher reaches of culinary status provided the rationale. Now, for example, reviews would begin with the assertion that Restaurant X didn’t represent, “the Italy of checkered tablecloths and melted candles in Chianti bottles, but the Italy of designer Giorgio Armani.”

It’s been quite a while since I’ve seen tables covered in red checks. Now it could be risky, suggesting not authenticity but tired mediocrity.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

March 30, 2014

Famous in its day: Tip Top Inn

As the massively solid Pullman Building was under construction on Michigan Avenue in Chicago in 1884, a young Adolph Hieronymus was traveling to Chicago from his native Germany. Within a few years he would run a restaurant of renown on the building’s top floor.

The building was to be the new headquarters of the Pullman Palace Car Company which manufactured sleeping and dining cars used by major railways. When the imposing building was completed, the company occupied two and a half of its nine floors while the rest of the space was rented for offices and what were known then as “bachelor apartments,” probably lacking anything but the most rudimentary cooking facilities.

The building was to be the new headquarters of the Pullman Palace Car Company which manufactured sleeping and dining cars used by major railways. When the imposing building was completed, the company occupied two and a half of its nine floors while the rest of the space was rented for offices and what were known then as “bachelor apartments,” probably lacking anything but the most rudimentary cooking facilities.

For the first few years the Pullman company ran its own restaurant, The Albion, on the 9th floor. It was considered advanced at the time to locate restaurants on top floors so that cooking odors would not drift throughout the building. In addition, diners at The Albion, and later the Tip Top Inn, had excellent views of Lake Michigan.

During the Columbian Exhibition in 1893 Adolph Hieronymus left his job as chef at the Palmer House and took over the Pullman building restaurant, renaming it the Tip Top Inn. Under his management, it became one of Chicago’s best restaurants, hosting society figures and professional organizations. Until the Pullman company expanded its offices onto all eight floors below the restaurant, men living in the 75 or so apartments on the upper floors were also steady customers of the Inn, often having meals sent down to them.

During the Columbian Exhibition in 1893 Adolph Hieronymus left his job as chef at the Palmer House and took over the Pullman building restaurant, renaming it the Tip Top Inn. Under his management, it became one of Chicago’s best restaurants, hosting society figures and professional organizations. Until the Pullman company expanded its offices onto all eight floors below the restaurant, men living in the 75 or so apartments on the upper floors were also steady customers of the Inn, often having meals sent down to them.

The space occupied by the Tip Top Inn was divided into a bewildering number of rooms, at least five and maybe more. Each had its own decorating scheme. Over the years – but surely not simultaneously — there were the Colonial Room [pictured at top ca. 1906], the Nursery, the Whist Room [pictured below], the Charles Dickens Corner, the Flemish Room, the French Room [pictured above], the Italian Room, the Garden Room, and the Grill Room. The Whist Room was decorated with enlarged playing cards and lanterns with spades, hearts, diamonds, and clubs. The lantern and suits also decorated the Inn’s china and menus.

The outlawing of alcoholic beverages proved challenging to the Tip Top Inn, as it did to other leading Chicago restaurants of the pre-prohibition era such as Kingsley’s, Rector’s, and the Hofbrau, all of which would go under before the ban on selling alcohol ended. Perhaps to attract new customers, Hieronymus created an associated restaurant on the 9th floor called The Black Cat Inn, with somewhat lower prices than the Tip Top Inn and a menu featuring prix fixe meals.

The outlawing of alcoholic beverages proved challenging to the Tip Top Inn, as it did to other leading Chicago restaurants of the pre-prohibition era such as Kingsley’s, Rector’s, and the Hofbrau, all of which would go under before the ban on selling alcohol ended. Perhaps to attract new customers, Hieronymus created an associated restaurant on the 9th floor called The Black Cat Inn, with somewhat lower prices than the Tip Top Inn and a menu featuring prix fixe meals.

The Black Cat was unusual at the time for having a staff of Black waitresses – who served in restaurants far less often than Black men. The Tip Top Inn, just like the Albion and the Pullman dining cars, had always been staffed with Black waiters, some of whom worked there for decades. It was said that anyone who worked at the Tip Top could find employment in any restaurant across the country. “Black Bolshevik” Harry Haywood wrote in his autobiography that he quickly worked his way up from Tip Top Inn busboy to waiter and then landed jobs on the ultra-modern Twentieth-Century Limited train and with Chicago’s Sherman Hotel and Palmer House.

By 1931 when the Tip Top Inn restaurant closed, it was regarded as an old-fashioned holdover from a previous era. Its extensive menu of specialties such as Stuffed Whitefish with Crabmeat and Suzettes Tip Top, some of the more than 100 dishes created by Hieronymus, was no longer in vogue. Aside from Prohibition, Hieronymus attributed the restaurant’s demise to the death of gourmet dining. Hieronymus died in1932 but he and his restaurant were remembered by Chicagoans for decades. The Pullman Building was demolished in 1956.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

March 23, 2014

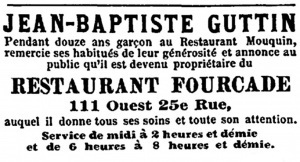

Find of the day: J.B.G.’s French restaurant

Last weekend I went to an antique paper show sponsored by the Ephemera Society of America where there were books and every sort of printed thing — maps, advertising cards, tickets, menus, postcards, posters, broadsides — for sale. I ended up buying only seven items, but one of them (shown above) was a gem.

I knew as soon as I spotted it that it was a relic of New York City’s old French quarter in which many restaurants flourished in the 19th century. The card probably dates from the latter years of the quarter, about 1904.

J.B.G.’s was operated by Jean Baptiste Guttin, who immigrated to the United States in 1872 and became a citizen in 1892. For many years he worked as a waiter at wine merchant Henri Mouquin’s well-known restaurant on Fulton Street. Then, in 1890, he took over a restaurant formerly run by A. Fourcade on West 25th street. Within a few years he changed the name to J.B.G. and moved down the street a bit.

Beginning in the 1890s the area from West 23rd to West 28th streets near Sixth avenue was the heart of the French quarter, which was said to be as much or more of a tight-knit community than the Chinese. It had earlier been situated farther downtown, south of Washington Square. By 1895 West 25th was the new restaurant row for French New Yorkers. The restaurants were also patronized by others who lived in the area, as well as adventurous “Bohemian” diners who came to soak up the atmosphere. Of course they also liked getting a six-course meal with red wine and coffee for 50 or 60 cents.

Beginning in the 1890s the area from West 23rd to West 28th streets near Sixth avenue was the heart of the French quarter, which was said to be as much or more of a tight-knit community than the Chinese. It had earlier been situated farther downtown, south of Washington Square. By 1895 West 25th was the new restaurant row for French New Yorkers. The restaurants were also patronized by others who lived in the area, as well as adventurous “Bohemian” diners who came to soak up the atmosphere. Of course they also liked getting a six-course meal with red wine and coffee for 50 or 60 cents.

Described in the 1903 guide book Where and How to Dine in New York as “very French,” J.B.G.’s was a truly old-fashioned table d’hôte in that customers had no choice in dishes and didn’t know what they would be eating until it was set down before them.

Jean Baptiste Guttin was successful in the restaurant business. When he died in 1914 he left the then-considerable sum of $4,000 to NYC’s French Hospital as a way of thanking the late chocolate-maker and restaurateur Henry Maillard for advancing him a loan of the same amount “in a moment of difficulty.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

March 16, 2014

Don’t play with the candles

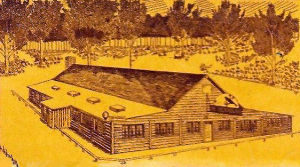

It’s not often that you run across a menu that tells patrons how to behave, right on the front. It seems to project the message Welcome! . . . or maybe not.

In case you were wondering what “trucking apart” means, I think it refers to flirting with someone other than who you came with.

The menu, which probably dates from the 1950s, is entertaining inside too: Pop Corn as an appetizer, Toast (under Specials, .20), Pickled Egg Salad with Crackers (.50), and Blackberry Wine from Ohio (.30 per glass).

The menu, which probably dates from the 1950s, is entertaining inside too: Pop Corn as an appetizer, Toast (under Specials, .20), Pickled Egg Salad with Crackers (.50), and Blackberry Wine from Ohio (.30 per glass).

The Nightingale’s finest and most elaborate offering is clearly its Chicken Dinner ($1.25). The potatoes, tomatoes, and biscuits get glowing modifiers while the chicken has none.

Tomato Soup or Tomato Cocktail

French Fried, Golden Brown Potatoes

Sliced Field Ripe Tomatoes

Peas or Beans

Piping Hot Biscuits

Coffee or Tea

Ice Cream

In 1940 Luther L. Dixon, an enterprising factory worker at American Tobacco Co. who made money in real estate, opened a restaurant/club called the Nightingale on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia. He had left the business by the mid 1950s, so the owner of the Nightingale with the menu advice, located south of Alexandria, may have been someone else.

In 1940 Luther L. Dixon, an enterprising factory worker at American Tobacco Co. who made money in real estate, opened a restaurant/club called the Nightingale on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia. He had left the business by the mid 1950s, so the owner of the Nightingale with the menu advice, located south of Alexandria, may have been someone else.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

March 9, 2014

Interview: who’s cooking?

Recently I interviewed someone who had cooked in a 24-hour restaurant located on the outskirts of a small Midwestern town in 1970.

Recently I interviewed someone who had cooked in a 24-hour restaurant located on the outskirts of a small Midwestern town in 1970.

He worked there one summer. He was the sole night shift kitchen staff from 10 pm to 6 am. Previous experience? One week as cook at a children’s summer camp the previous year.

He was 16 years old.

Although he gave it little thought at the time, he now suspects the restaurant was designed, owned, and operated by the food processing company that supplied the food, the menus, the “recipes” – in short, everything. Follow-up research revealed that the company supplied 1,500 restaurants, schools, and institutions in four states.

The building was new and blandly modern. It was surrounded by a parking lot. Through a big plate glass front window was a view of an interior with booths, formica-topped tables and chairs, and a counter with stools. The decor, as he remembers it, contained multi-colored hanging lights, fake stone, and grill work in a coordinated style he calls “corporate.” About 60 people could be seated. At night, except right after the bars closed on weekends, there were rarely more than a dozen patrons at any one time.

The building was new and blandly modern. It was surrounded by a parking lot. Through a big plate glass front window was a view of an interior with booths, formica-topped tables and chairs, and a counter with stools. The decor, as he remembers it, contained multi-colored hanging lights, fake stone, and grill work in a coordinated style he calls “corporate.” About 60 people could be seated. At night, except right after the bars closed on weekends, there were rarely more than a dozen patrons at any one time.

Most of the night customers were working men, traveling salesmen, work crews, people passing through town. It wasn’t much of a local hangout, unlike the bowling alley restaurant at the other end of town. It served no alcohol.

Was there a chef at this restaurant? Answer: prolonged laughter. The manager had preprinted forms on which he checked off what supplies were needed.

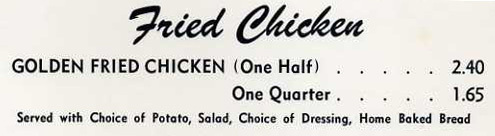

A popular order, particularly with the barflies, was steak and eggs ($2.50 with toast and coffee). Eggs were one of the few items of fresh food in the kitchen other than lettuce and tomatoes. “Everything was frozen so once you knew how to deep fry it or put it in the Lytton [microwave] oven, you were set,” he said. This included pies (“Served Hot from Our Electronic Ovens”), Cordon Bleu, Breaded Pork Tenderloin, Golden Fried Chicken, and Fillet of Perch. Potato Salad came in a tub, Soup of the Day in giant cans. Hard boiled egg came in a long tube so that every slice was the same. Home Baked Bread? Well, I think you know.

A popular order, particularly with the barflies, was steak and eggs ($2.50 with toast and coffee). Eggs were one of the few items of fresh food in the kitchen other than lettuce and tomatoes. “Everything was frozen so once you knew how to deep fry it or put it in the Lytton [microwave] oven, you were set,” he said. This included pies (“Served Hot from Our Electronic Ovens”), Cordon Bleu, Breaded Pork Tenderloin, Golden Fried Chicken, and Fillet of Perch. Potato Salad came in a tub, Soup of the Day in giant cans. Hard boiled egg came in a long tube so that every slice was the same. Home Baked Bread? Well, I think you know.

The food images shown in this post are stickers applied to the restaurant’s menu before the entire thing was plasticized. I take them to be generic, as I do the meaningless logo from the menu’s cover which looks like it was intended for a “steak & ale” eatery.

The food images shown in this post are stickers applied to the restaurant’s menu before the entire thing was plasticized. I take them to be generic, as I do the meaningless logo from the menu’s cover which looks like it was intended for a “steak & ale” eatery.

With some orders he got to do what he considered “actual cooking”: “Liver and onions. You have to make the bacon and onions – that was actual cooking. Denver omelet, that was actual cooking.” He enjoyed making sandwiches at the deli counter. One of his personal favorites was the Denver Sandwich — chopped ham, pickle, and scrambled egg made in a patty and served on toasted bread. He also enjoyed cottage cheese and pineapple.

Diners rarely sent food back to the kitchen. “It’s amazing how many different kinds of food that a 16-year old could cook and not ruin anything. I was feeding a lot of people with a lot of liability and it didn’t go wrong,” he said. The manager criticized him for one thing only: giving customers too many french fries. Limit them to a handful, insisted the manager. So he garnished the plates with parsley and “Never got in trouble for using too much parsley.”

Diners rarely sent food back to the kitchen. “It’s amazing how many different kinds of food that a 16-year old could cook and not ruin anything. I was feeding a lot of people with a lot of liability and it didn’t go wrong,” he said. The manager criticized him for one thing only: giving customers too many french fries. Limit them to a handful, insisted the manager. So he garnished the plates with parsley and “Never got in trouble for using too much parsley.”

Despite all, he had surprising praise for his old workplace, saying, “I was impressed with the efficiency of the kitchen. It was easy to work in. I liked that there was a ready supply of clean linens.” He added, “There were not many dining establishments. Before Applebee’s this filled a niche. It was more ambitious food than people had access to before.”

Did he ever return there as a customer? “No,” he said, “I had no warm fuzzy feeling for the place.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2014