Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 38

July 24, 2013

Mob restaurants

Gangster stories run like a red thread through the 20th-century history of American restaurants, from the speakeasies of the 1920s, to the shakedowns and union infiltration of the 1930s, the rackets of the 1940s and 1950s, and the later years of money laundering and loudly proclaimed legitimate business.

Gangster stories run like a red thread through the 20th-century history of American restaurants, from the speakeasies of the 1920s, to the shakedowns and union infiltration of the 1930s, the rackets of the 1940s and 1950s, and the later years of money laundering and loudly proclaimed legitimate business.

But what seems to interest Americans the most are restaurants mobsters are alleged to patronize, and all the more so if there has been a legendary shootout there.

As portrayed in the film Dinner Rush, even rumors that a restaurant is a gangland favorite can boost its popularity immensely. The film was made by Bob Giraldi who’s been inside the restaurant business.

On July 28 a series called Inside the American Mob will begin on the National Geographic channel. My friend and neighbor John Marks, supervising producer, inspired this post when he mentioned the popularity of restaurants where mobsters have been gunned down.

On July 28 a series called Inside the American Mob will begin on the National Geographic channel. My friend and neighbor John Marks, supervising producer, inspired this post when he mentioned the popularity of restaurants where mobsters have been gunned down.

Violence is abundant in restaurant history. Two of the worst mass murders in the United States took place in restaurants, the killing of 23 people at Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen TX in 1991 and 21 at a McDonald’s in San Ysidro CA in 1984. Those tragic events did not bring about an influx of patrons wanting to soak up evil ambiance. Quite the contrary. Luby’s remodeled and reopened but never regained the business it once had, closing the Killeen site for good in 2000. McDonald’s razed the blighted unit in San Ysidro, rebuilding nearby.

On the other hand, when gangsters are shooting victims people are unmoved, evidently figuring they got what was coming to them. The absence of bullet holes and bloodstains disappoints.

Restaurants that are linked to mobsters, such as NYC’s Sparks Steak House, where Paul Castellano was killed as he stepped out of his car, do not always appreciate being included in guide books such as A Goodfellas Guide to New York just because a mobster sometimes ate there. I can’t blame them. Who would want tourists dressed in shorts and tee shirts turning up at your high priced restaurant? The mob is not what it used to be. Yet I have to wonder, is there an American restaurant that can be absolutely certain it has never hosted mobsters?

I’ll also point out that not all mob-connected restaurants are or have been Italian. Also, probably every ethnic group has had its own version of the Mafia at some point.

Most major cities in the U.S. have had restaurants that served as gangster hangouts. [pictured: the Cicero IL headquarters of Al Capone, ca. 1939] Chicago’s Colosimo’s was already in the books by 1930, ten years after its owner “Big Jim” Colosimo became one of the first victims of a gangland shooting in a restaurant. As late as 1958 when a new owner of the property announced he would raze the building, the site was overrun with an estimated 1,000 souvenir hunters. In the 1920s and 1930s even “nice” St. Paul MN could boast of four or five nightclub eateries with underworld associations, according to the authors of Minnesota Eats Out. Other mob-connected eating places illustrated in this post are Louigi’s in Las Vegas and Villa Venice outside Wheeling IL.

Most major cities in the U.S. have had restaurants that served as gangster hangouts. [pictured: the Cicero IL headquarters of Al Capone, ca. 1939] Chicago’s Colosimo’s was already in the books by 1930, ten years after its owner “Big Jim” Colosimo became one of the first victims of a gangland shooting in a restaurant. As late as 1958 when a new owner of the property announced he would raze the building, the site was overrun with an estimated 1,000 souvenir hunters. In the 1920s and 1930s even “nice” St. Paul MN could boast of four or five nightclub eateries with underworld associations, according to the authors of Minnesota Eats Out. Other mob-connected eating places illustrated in this post are Louigi’s in Las Vegas and Villa Venice outside Wheeling IL.

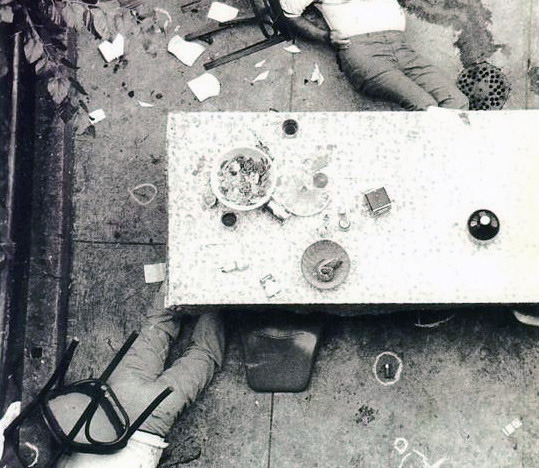

New York City and environs takes the prize for gangland restaurants, among which are restaurants where mobsters, their henchmen, and associates have met a messy end. Few still exist or remain in their original locations. To name some, both present and past: Nuova Villa Tammaro, Coney Island (Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria,1931); Palace Chop House, Newark (Dutch Schultz, 1935); Umberto’s Clam House, Little Italy (Joey Gallo, 1972); Joe & Mary, Brooklyn (pictured at top, Carmine Galante, 1979); Broadway Pub, Manhattan; La Stella, Queens; King Wah, Chinatown; Villa Capri, Long Island; Sparks, Manhattan (Paul Castellano, 1985); Bravo Sergio, Manhattan (Irwin Schiff, 1987).

New York City and environs takes the prize for gangland restaurants, among which are restaurants where mobsters, their henchmen, and associates have met a messy end. Few still exist or remain in their original locations. To name some, both present and past: Nuova Villa Tammaro, Coney Island (Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria,1931); Palace Chop House, Newark (Dutch Schultz, 1935); Umberto’s Clam House, Little Italy (Joey Gallo, 1972); Joe & Mary, Brooklyn (pictured at top, Carmine Galante, 1979); Broadway Pub, Manhattan; La Stella, Queens; King Wah, Chinatown; Villa Capri, Long Island; Sparks, Manhattan (Paul Castellano, 1985); Bravo Sergio, Manhattan (Irwin Schiff, 1987).

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

July 17, 2013

As the restaurant world turned, July 17

July 17 being the anniversary of my blog, I’m celebrating. In the beginning I thought a blog would be so easy. I’d browse over my notes, grab a few things, and write a post in half an hour. Hah! That was approximately true of the first few posts — one of which I’ve revised repeatedly and another of which I’ve deleted. In memory of that happy delusion I present a quick rundown of restaurant happenings on random July 17ths.

1890 – Waiters walking off the job close down three more restaurants as they join a St. Louis waiters’ strike. The Waiters’ Union is further heartened when it learns that members of the city’s Typographical Union have pledged not to eat anywhere non-union servers are employed.

1907 – A Bangor ME restaurant worker grinding clams for chowder runs into a hard substance which turns out to be a pearl. She rejects a local jeweler’s offer of $250 ($5,000 or $6,000 today) saying she will instead send it to New York for appraisal.

1907 – A Bangor ME restaurant worker grinding clams for chowder runs into a hard substance which turns out to be a pearl. She rejects a local jeweler’s offer of $250 ($5,000 or $6,000 today) saying she will instead send it to New York for appraisal.

1916 – Taylor’s Exchange Restaurant opens in a new building in Charleston SC promising there will be “no odors” since the kitchen is upstairs from the dining room. Taylor signs his advertisement, “I remain, Yours When Hungry.”

1930 – Despite his claims that he does not run a “booze joint” and had no idea liquor was hidden in his lunchroom’s walls, a judge fines the operator of Holyoke MA’s Washington Lunch $150.

1936 – Admitting she only took a restaurant job to escape “that darn farm” in Florida where she grew up, an Atlanta waitress announces she has won a scholarship to Louisiana State and will be quitting to study music there.

1950 – Fifteen members of the Washington, D.C. Interracial Workshop are arrested for holding up the line at Sholl’s Cafeteria after Afro-Americans in the group are denied service.

1958 – Although she was threatened with bodily harm, Beverly Sturdevant, a manager of the Embassy Restaurant in Cicero IL, testifies against mobsters inside Local 450 of the Chicago Hotel and Restaurant Employes Union to the US Senate Rackets Investigating Committee.

1958 – Although she was threatened with bodily harm, Beverly Sturdevant, a manager of the Embassy Restaurant in Cicero IL, testifies against mobsters inside Local 450 of the Chicago Hotel and Restaurant Employes Union to the US Senate Rackets Investigating Committee.

1962 – “Reverse Freedom Rider” David Harris announces he will open a barbecue and chili restaurant in Hyannis MA, summer home of the Kennedys. Harris arrived a few months earlier with a busload of Afro-Americans sent North by an Arkansas segregationist Citizens’ Council. The action was meant to embarrass President John F. Kennedy, who had recently taken a harder line on segregation.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

July 14, 2013

Dining in summer

For most of restaurant history proprietors watched their business drop off drastically in summer.

Not only did patronage decline but those who showed up ate less. In the 1890s many asked for crackers and milk in place of the usual steaks and chops. Orders for hot coffee fell off by a third or more. Around 1911 lunch rooms had become used to customers who ate nothing but a dish of ice cream. In the 1920s sandwiches and salads were popular. An August 1925 restaurant journal bewailed “the diner who doesn’t eat enough,” typified by the man whose cafeteria tray held only a measly dish of cottage cheese and a corn cob.

Food did not stand up well to the heat. Salt shakers became clogged, butter melted, oils turned rancid, and vermin multiplied. In 1882 a Chicagoan was disgusted by “butter the consistency of salad-oil, dotted with struggling flies.” Restaurants that put food on display, as many once did, were in danger of turning their patrons’ stomachs with what in effect had become an advertisement for not eating there.

Food did not stand up well to the heat. Salt shakers became clogged, butter melted, oils turned rancid, and vermin multiplied. In 1882 a Chicagoan was disgusted by “butter the consistency of salad-oil, dotted with struggling flies.” Restaurants that put food on display, as many once did, were in danger of turning their patrons’ stomachs with what in effect had become an advertisement for not eating there.

People’s moods were likely to sour along with dairy products. Servers were surly and the kitchen received more complaints than usual from dissatisfied customers.

It’s hard to imagine sitting in a stifling dining room wearing a suit and tie but that was the requirement for men in most restaurants before World War I. In 1911 it took a dire July heat wave in Cleveland for downtown eateries there to permit men to dine in shirt sleeves.

Restaurants tried all kinds of things to deal with the summer doldrums. In 1797 Boston’s Julien offered a range of (dubious?) remedies “calculated for strengthening and invigorating the system of nature, during the heat of Summer” which included vinegars and white wines. Another solution was to open a summer garden. Before the Civil War Delmonico’s opened a garden attached to their Brooklyn vegetable and dairy farm. Other restaurants took to the roof for a whiff of breeze.

Restaurants might shut down their city restaurants or open seasonal branches in resort areas. Brooklyn’s Gage & Tollner had a custom of closing up for summer altogether. Portland’s Exchange Restaurant in Maine opened a branch on the city’s Long Island in the 1890s where it hosted clam bakes and shore dinners. The English Tea Rooms near the Waldorf in NYC migrated to Newport and Northampton’s Rose Tree Inn moved to Maine while its principal customers, Smith College students, took summer vacation.

In the 1880s the more modern restaurants were equipped with fans driven by steam or electric dynamos in the basement. The New York Kitchen, a mass feeding establishment serving up to 2,000 meals a day, advertised in 1888 that it was the coolest restaurant in Chicago “made so by our steam exhaust fan, which introduces 15,000 cubic feet of fresh air every minute.” The so-called “quick lunch” eateries of the 1890s – forerunners to today’s fast food establishments – led the way with modern methods of buying, food preparation, and facilities equipped with ceiling fans. But the average, undercapitalized restaurant could not afford such luxuries and made do with paper fans. (Um, and pretend it’s electric?)

In the 1880s the more modern restaurants were equipped with fans driven by steam or electric dynamos in the basement. The New York Kitchen, a mass feeding establishment serving up to 2,000 meals a day, advertised in 1888 that it was the coolest restaurant in Chicago “made so by our steam exhaust fan, which introduces 15,000 cubic feet of fresh air every minute.” The so-called “quick lunch” eateries of the 1890s – forerunners to today’s fast food establishments – led the way with modern methods of buying, food preparation, and facilities equipped with ceiling fans. But the average, undercapitalized restaurant could not afford such luxuries and made do with paper fans. (Um, and pretend it’s electric?)

Movie theaters, passenger trains, and restaurants were among the first businesses to install air-conditioning in the late 1920s and 1930s, but it was still fairly rare in restaurants before WWII. The largest restaurants and chains such as S&W cafeterias and Toffenetti’s were in the lead. In New Orleans, Gluck’s (“serving more than 10,000 meals a day”) was air-conditioned by 1930. In the mid-1930s federally backed modernization loans helped, but it was still common to see restaurants in smaller cities at the time advertising that they were “the only” air-conditioned restaurant in, say, Rockford IL or New Bedford MA.

Movie theaters, passenger trains, and restaurants were among the first businesses to install air-conditioning in the late 1920s and 1930s, but it was still fairly rare in restaurants before WWII. The largest restaurants and chains such as S&W cafeterias and Toffenetti’s were in the lead. In New Orleans, Gluck’s (“serving more than 10,000 meals a day”) was air-conditioned by 1930. In the mid-1930s federally backed modernization loans helped, but it was still common to see restaurants in smaller cities at the time advertising that they were “the only” air-conditioned restaurant in, say, Rockford IL or New Bedford MA.

There can be little doubt that air-conditioning was attractive to customers. During WWII Gimbels in Philadelphia, where all six of its restaurants and private dining rooms were air-conditioned, was serving up to 23,000 meals a day. Needless to say, today it is considered a must.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

July 7, 2013

Dining by gaslight

Though it seems fairly obvious when you think about it, the development of entertainment districts post-WWII encouraged the growth of restaurant-ing in many cities across the U.S. On the minus side, the fate of such restaurants was highly dependent upon the fate of the districts.

Though it seems fairly obvious when you think about it, the development of entertainment districts post-WWII encouraged the growth of restaurant-ing in many cities across the U.S. On the minus side, the fate of such restaurants was highly dependent upon the fate of the districts.

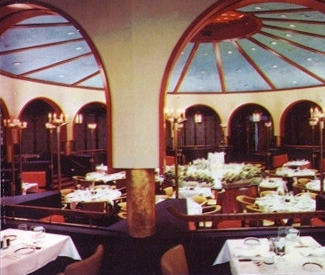

The Three Fountains [pictured] was the star restaurant in the entertainment district of St. Louis which began in the late 1950s and was officially named Gaslight Square in 1961. The one-and-one-half block area attracted affluent suburban St. Louisans and the city’s many conventioneers with restaurants, live theater, and clubs that featured national acts such as the Smothers Brothers, Joni Mitchell, Lenny Bruce, and Miles Davis.

Developing out of a racially borderline, transitional neighborhood populated with apartments, music schools, and antiques stores, its pioneering establishments included the Crystal Palace theater, the Gaslight Bar, Smokey Joe’s Tavern, the Laughing Buddha coffeehouse, and the Dark Side jazz club.

The Three Fountains exuded luxury with a multi-level interior lavishly decorated with antique fixtures complemented by an oversize menu filled with expensive dishes (the $6.50 pepper steak would cost about $46 today). Its decor, like most of the restaurants and clubs in Gaslight, consisted of an extravagant, crazy melange of salvaged windows, doors, railings, paneling, statues, fountains, and light fixtures from structures mowed down by a city obsessed with urban renewal.

The Three Fountains exuded luxury with a multi-level interior lavishly decorated with antique fixtures complemented by an oversize menu filled with expensive dishes (the $6.50 pepper steak would cost about $46 today). Its decor, like most of the restaurants and clubs in Gaslight, consisted of an extravagant, crazy melange of salvaged windows, doors, railings, paneling, statues, fountains, and light fixtures from structures mowed down by a city obsessed with urban renewal.

Slum clearance in an area known as Mill Creek Valley brought its bounty. There the destruction of residences formerly housing 20,000 people (95% of them Afro-Americans) freed up tons of antique woodwork and hardware for decorators with a taste for Victorian. The transfer of objects from Mill Creek to the nightclubs and restaurants in Gaslight Square can also be seen as an illustration of a troubled relationship with the city’s black population who lived close by, worked in Gaslight’s restaurants, and performed in its clubs, yet whose patronage was not welcome.

Slum clearance in an area known as Mill Creek Valley brought its bounty. There the destruction of residences formerly housing 20,000 people (95% of them Afro-Americans) freed up tons of antique woodwork and hardware for decorators with a taste for Victorian. The transfer of objects from Mill Creek to the nightclubs and restaurants in Gaslight Square can also be seen as an illustration of a troubled relationship with the city’s black population who lived close by, worked in Gaslight’s restaurants, and performed in its clubs, yet whose patronage was not welcome.

According to Jorge Martinez, owner of a couple of jazz clubs, the block’s business association ruled against his proposal for a dance hall out of fear it would attract Afro-Americans. Terry Kennedy, an Afro-American who grew up in the neighborhood adjacent to the area and became a city alderman in 1989, observed that if you were black “you better not be there too long, or the police would run you off.” (Interviews with Kennedy, Martinez, and others are found in the book Gaslight Square, an Oral History, by Thomas Crone.)

Yet, Gaslight Square offered opportunity to a few Afro-Americans. Sandra J. Parks occupied a rare position in America, that of black female chef. She cooked in several of the area’s better restaurants, including Kotobuki and Port St. Louis and managed Two Cents Plain before moving to Chicago for a career in catering.

Compared to the city as a whole, Gaslight Square was a somewhat integrated area. Nonetheless racial tension would become a major factor in its downfall, most evident in white patrons’ grossly exaggerated fear of black-on-white crime.

From the area’s beginnings as an entertainment zone to its serious decline by 1968, at least 20 restaurants, dozens of nightclubs, and numerous coffeehouses and theaters were in business there [see map]. After-hour parties took place above street level, in apartment buildings and flats.

There were steakhouses (Magnolia House, Marty’s, Jacks or Better, Mr. D’s), two Mexican restaurants (Tortilla Flat and a branch of Chicago’s La Margarita), a Polynesian restaurant (The Islander), a Japanese restaurant where servers dressed as geishas (Kotobuki), a fish restaurant where servers dressed as sailors (Port St. Louis), a Greek restaurant (Smokey Joe’s Grecian Tavern), a deli (Two Cents Plain), an Italian eatery (Bella Rosa), a tavern (O’Connell’s Pub), and several places whose cuisine I could not determine (Red Carpet, The Georgian, Carriage House, Die Lorelei, Left Bank).

Many of the restaurants were in converted town houses. Whenever possible they had patio dining in front, and most featured entertainment such as cabaret, folk music, or Dixieland, ragtime, or cool jazz. The more expensive restaurants were first to suffer from the area’s decline as well-dressed, well-heeled customers stopped coming. Conventioneers were warned off, in many cases, by cabdrivers who refused to drive there. Clubs with go-go dancers in the windows displaced coffeehouses with folksinging and poetry as a younger, more casually dressed crowd took over.

The more expensive restaurants were first to suffer from the area’s decline as well-dressed, well-heeled customers stopped coming. Conventioneers were warned off, in many cases, by cabdrivers who refused to drive there. Clubs with go-go dancers in the windows displaced coffeehouses with folksinging and poetry as a younger, more casually dressed crowd took over.

Although Gaslight Square was in ways a model for Chicago’s Old Town and Omaha’s Old Market, many businesses began closing or moving away by the mid 1960s. Port St. Louis and Two Cents Plain moved to more promising locations. In 1965 Craig Claiborne gave the Three Fountains a short – and horrid — review (“It is said to be the only French restaurant in the city and, if this is true, it is unfortunate.”) A few years later a number of gaslights were extinguished for nonpayment of gas bills. By 1972 when O’Connell’s moved to South Kingshighway, the area was largely in ruins.

Aside from a memorial constructed out of the pillars that once stood outside Smokey Joe’s, not a trace of Gaslight Square remains standing today.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

June 27, 2013

Anatomy of a restaurateur: Charles Sarris

It is always a big deal to me when I find a restaurant proprietor’s memoir, all the more so when he or she conducted an “everyday” sort of restaurant. My Ninety-Five Year Journey, privately published by Charles N. Sarris in 1987, was a just such a wonderful, and rare, find.

The book illustrates a fairly typical restaurant career for thousands of Greek-Americans who opened restaurants in small towns which had few eating places in the early decades of the 20th century.

Charles was born in Lesbos, Greece, in 1891. At 19 he lived in dread that any moment he would be conscripted into the Turkish army and, possibly, spend the rest of his life in an occupied country. He decided to leave for the U.S. For the next six years he bounced around Connecticut and Massachusetts, working in Greek-owned confectioneries where he learned to make candy and ice cream. In 1916 he went to work in a new confectionery in Amherst MA, population 5,500. It wasn’t long before Charles and his partners, who included his brother James, took over the confectionery and expanded it into a lunchroom serving basic fare such as hamburgers and ham and eggs.

The restaurant was named the College Candy Kitchen [1921 advertisement pictured], obviously aimed at student patrons from Amherst College and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts). Candy Kitchens run by Greek entrepreneurs could be found throughout the United States in the early 20th century. Coincidentally, another “College Candy Kitchen” did business in Cambridge’s Harvard Square.

The restaurant was named the College Candy Kitchen [1921 advertisement pictured], obviously aimed at student patrons from Amherst College and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts). Candy Kitchens run by Greek entrepreneurs could be found throughout the United States in the early 20th century. Coincidentally, another “College Candy Kitchen” did business in Cambridge’s Harvard Square.

One of only three Greeks in Amherst when he arrived, Charles would not feel welcome in his new home for some time. He heard racial and ethnic slurs unfamiliar to him from his previous residency in Andover MA. He observed that many townspeople valued people from France, Germany, or England more highly than those from Italy, Poland, the Middle East, or Greece.

In 1927 he and two other merchants who occupied the three-story building located on Main Street across from Amherst town hall formed Amherst Realty Co. to buy the property. Yet not until 1939, after running a thriving restaurant for 23 years, did Charles finally gain admission into one of the town’s fraternal organizations, the Rotary Club.

The College Candy Kitchen modernized and expanded in the 1920s [1920s Spanish-style interior shown], despite a disastrous fire in 1928 which necessitated moving to a new location for several months. Business slowed drastically but Charles and James got through the Depression ok.

Students, who made up the bulk of customers, balked when the restaurant introduced new foods such as yogurt and melons. Some greeted watermelon with the objection, “Gee, we’re not Alabama Negroes!” Charles reassured them that the menu would always include staples such as boiled dinners, baked beans, and meatloaf. For decades the restaurant continued to produce its own baked goods, ice cream, and, for holidays, candy.

Once again Charles encountered customer resistance when he hired Afro-Americans as staff or served them as patrons. “We had a lot of opposition from the students but we ignored it,” he wrote. Eventually they settled down and got used to it.

According to Charles, the restaurant closed in 1953 due to illness, parking problems, and customers’ demands for alcoholic beverages (which he did not wish to deal in). It was succeeded by the Town House Restaurant. A 1953 bankruptcy auction notice gave a fair idea of the size of the restaurant then. On the auction block were 30 leather upholstered booths, two circular booths, four showcases, a soda fountain with 12 stools, and kitchen, bakery, and ice cream equipment. I can just picture it.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

June 18, 2013

Women’s restaurants

Not all restaurants have been purely, or even mainly, commercial ventures. This was particularly true of women’s suffrage eating places and those of the 1970s feminist movement.

Although the women’s restaurants of these two periods were quite different in some ways, they shared a dedication to furthering women’s causes and giving women spaces of their own in which to eat meals, hold meetings, and in the 1970s, to enjoy music and poetry by women.

In the 1910s most major U.S. cities had at least one suffrage restaurant, tea room, or lunch room sponsored by an organization such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

In the 1910s most major U.S. cities had at least one suffrage restaurant, tea room, or lunch room sponsored by an organization such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

As was true of later feminist restaurants, those of the suffrage era tended to be small and undercapitalized. An exception was the suffrage restaurant financed by the wealthy socialite Alva Belmont in NYC. In terms of patronage, it was almost certainly the most successful women’s restaurant of either era. It reportedly served 900 meals per day from a low-priced menu on which most items were 5 or 10 cents and consisted of soup, fish cakes, baked beans, and home-made pie.

Suffrage restaurants admitted men and welcomed the opportunity to ply them with leaflets and home-made soups, salads, and fritters that would incline them to support the cause. An aged Philadelphia activist recalled in 1988, “I worked at a suffrage tea room. We lured men in, for a good, cheap business lunch. Then you could hand them literature and talk.” In the NYC restaurant operated by NAWSA in 1911, it was impossible to ignore the suffrage issue since every dish, glass, and napkin bore script saying Votes for Women.

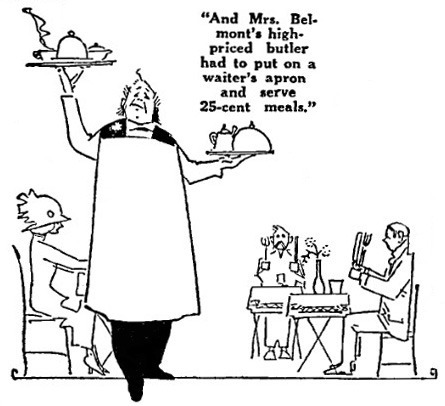

Though dedicated to women’s causes, women’s restaurants were not free of conflict. Many suffragists objected to how Alva Belmont ruled with an iron fist, brusquely ordering servers around until they walked out on strike, followed by the dishwashers. Belmont was ridiculed when she brought in her butler and footman to fill the gap. Her footman quit too. Some feminist restaurants experienced discord over cooperative management and, especially, whether or not to serve men.

Though dedicated to women’s causes, women’s restaurants were not free of conflict. Many suffragists objected to how Alva Belmont ruled with an iron fist, brusquely ordering servers around until they walked out on strike, followed by the dishwashers. Belmont was ridiculed when she brought in her butler and footman to fill the gap. Her footman quit too. Some feminist restaurants experienced discord over cooperative management and, especially, whether or not to serve men.

The first feminist restaurant, NYC’s Mother Courage, was founded in April of 1972. (Its co-founder Dolores Alexander discussed it in 2004-2005 interviews.) Others established in the 1970s included Susan B. Restaurant, Chicago; Bread & Roses, Cambridge MA; The Brick Hut, Berkeley CA; Los Angeles Women’s Saloon and Parlor, Hollywood CA; and Bloodroot, Bridgeport CT). Undoubtedly there were more, especially in college towns like Eugene OR and Iowa City IA. In the 1980s a number of women’s coffeehouses appeared, but they were performance spaces more than eating places.

As part of the counterculture, 1970s feminist restaurants typically aimed at a broad set of goals. Women’s equal position in society was paramount but it was embedded in a project of establishing a more peaceful and egalitarian world. Feminist restaurants rotated jobs and paid everyone the same wages. They raised capital by small donations from friends. Staffs were entirely female and women also did most of the renovating. Their decor was spare, with exposed brick walls, mismatched furniture, and chalkboard menus. They served simple peasant-style food, usually prepared from scratch. Some served wine and beer. More often than not menus were vegetarian, or at least beef-less. The L. A. Women’s Saloon and Parlor supported farm workers and would not serve grapes or lettuce. The Brick Hut boycotted Florida orange juice during the anti-gay campaign of spokesperson Anita Bryant. The Women’s Saloon avoided diet plates and sodas, deeming them insulting to large-sized women.

Many proponents of feminist restaurants felt that women were often treated poorly in restaurants, many of which regarded men as their prime customers. Feminist restaurants made a point of presenting women dining with men with the check and wine to sample. But for many women patrons, perhaps especially lesbians, the enjoyment of a non-hostile space was more significant.

At some point each feminist restaurant confronted the touchy question of whether they would serve men. Considerable acrimony erupted around this question at the Susan B. Restaurant in Chicago and Bread & Roses in Cambridge, resulting in the former restaurant’s closure after only a few months. At Bread & Roses a co-founder exercised non-consensus managerial power and fired a server who made men and some heterosexual women feel unwelcome, setting off rounds of group meetings. The restaurant, opened in 1974, was put up for sale and in 1978 became the short-lived “women only” Amaranth restaurant and performance space.

Today Bloodroot may be the sole survivor of the feminist restaurant era.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

June 11, 2013

Restaurant history day

Yesterday I was fully immersed in restaurant history. Starting off the day I had an e-mail exchange with a local 1970s activist about a feminist restaurant that once operated in Northampton MA. Next I had an interesting phone call from a researcher in Minneapolis who has unearthed the early 20th-century history of Greek immigrant restaurant and confectionery proprietors in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Then, while surfing a Facebook page about my former hometown of Webster Groves, Missouri, I discovered a discussion about a long gone restaurant there that refused to serve Afro-Americans.

Yesterday I was fully immersed in restaurant history. Starting off the day I had an e-mail exchange with a local 1970s activist about a feminist restaurant that once operated in Northampton MA. Next I had an interesting phone call from a researcher in Minneapolis who has unearthed the early 20th-century history of Greek immigrant restaurant and confectionery proprietors in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Then, while surfing a Facebook page about my former hometown of Webster Groves, Missouri, I discovered a discussion about a long gone restaurant there that refused to serve Afro-Americans.

The name of the restaurant was the Toll House. I never went inside but as a child I formed the impression that it was a place where old-line Webster Grovesians went to eat club sandwiches and fruit cocktail appetizers on the nights their maids were off. Since Webster Groves was a dry town then, it was a restaurant that my parents would never have chosen – no Manhattans!

The name of the restaurant was the Toll House. I never went inside but as a child I formed the impression that it was a place where old-line Webster Grovesians went to eat club sandwiches and fruit cocktail appetizers on the nights their maids were off. Since Webster Groves was a dry town then, it was a restaurant that my parents would never have chosen – no Manhattans!

An undated menu reveals that the Toll House had some surprisingly (to me) upscale dishes considering its rather drab appearance and its location in a dry, Waspy suburb of St. Louis – Oysters Rockefeller (.75), Pompano (.85), Lobster (1.25), Chateaubriand (1.35), and Baked Alaska (.40).

An undated menu reveals that the Toll House had some surprisingly (to me) upscale dishes considering its rather drab appearance and its location in a dry, Waspy suburb of St. Louis – Oysters Rockefeller (.75), Pompano (.85), Lobster (1.25), Chateaubriand (1.35), and Baked Alaska (.40).

The Toll House was the site of pickets and sit-ins against racial discrimination in 1961 and 1962. Sadly, the city of Webster Groves seemed all too ready to arrest protestors. Just how many protests took place there is unclear, but I have found evidence of at least four. In the summer of 1961, two women picketers were arrested outside the restaurant after the proprietor Myrtle Eales, who ran the restaurant with her husband Forrest, claimed they had pushed her in a scuffle. In January of 1962 thirteen black and white members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) were arrested for trespassing after they occupied the restaurant for four hours without being served. Although it was a cold winter day, the owners turned the heat off and the air conditioning on in an attempt to get them to leave. That same month a group of four protestors were locked in the restaurant’s vestibule for two hours. Then in April of 1962 three white protestors, all airmen from an Illinois military base, were arrested by Webster Groves police on suspicion of being AWOL (they weren’t).

The embattled restaurant did not survive the protests. I believe it closed in 1962.

Strangely enough, the otherwise obscure Toll House had made the national news earlier when it was featured in a 1944 Life magazine article about (white) teen-age social life. At that time it was a lunch counter popular with teens for hanging out. According to a letter sent to Life after the article appeared, whoever owned the restaurant then wanted young patrons to keep out. In a large advertisement in a local newspaper the management informed parents that their unruly children were bending silverware, breaking glasses, setting napkins on fire, carving up tabletops, and destroying stools.

In 1966 the CBS documentary “Sixteen in Webster Groves” appeared, portraying the suburb’s teenagers as spoiled, conformist, and more concerned about having a nice house with gleaming silverware than with the Vietnam war or civil rights. Residents were unhappy with what they felt was a false portrayal but, I wonder, was it completely off base?

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

June 3, 2013

Charge it!

The advent of travel and entertainment (T&E) credit cards in the 1950s was instrumental in sparking a renaissance in luxury restaurants that hadn’t been seen since pre-Prohibition days.

The advent of travel and entertainment (T&E) credit cards in the 1950s was instrumental in sparking a renaissance in luxury restaurants that hadn’t been seen since pre-Prohibition days.

Nowhere was the effect felt more strongly than in NYC, birth site of Diners’ Club.

On February 8, 1950, Frank McNamara paid for his lunch at a steak house called Major’s Cabin Grill in NYC with a Diners’ Club card numbered 1,000 (i.e., #1). With his little paper card he made the very first charge on a nationwide credit card.

The timing of the Diners’ Club launch was perfect. During World War II expense accounts had proliferated as a way companies could use income for entertaining clients rather than hand it to the government as a tax on “excess” profits (profits greater than those before the war). Now, in 1950, the excess profits tax lifted at the end of WWII was only a few months away from reinstatement for the Korean War.

The growth of T&E credit cards went hand in hand with the growth of expense accounts. As one publication put it, credit cards were spinoffs of expense accounts. And, each time the IRS tightened up its requirements for itemizing deductions, more credit card applications came in.

Unlike the nationwide bank cards that would eventually swamp T&E cards, the latter required high financial standing, an annual membership fee, and full payment of balances within 30 days. Having one of these cards brought cachet.

Unlike the nationwide bank cards that would eventually swamp T&E cards, the latter required high financial standing, an annual membership fee, and full payment of balances within 30 days. Having one of these cards brought cachet.

Following quickly on the heels of the Diners’ Club launch came many others: Dine ’n Sign, National Credit Card, Your Host, Inc, Duncan Hines’ Signet Club, the American Hotel Association’s Universal Travelcard, Hilton’s Carte Blanche, the Esquire Club, and the Gourmet Guest Club (the last two linked to Esquire and Gourmet magazines). A smaller Diners’ Club continues today, but the only other survivor is American Express, which inaugurated its credit card in 1958, then quickly rose to the top of the T&E field.

Traveling salesmen and men (rarely women) in industries such as public relations, advertising, publishing, manufacturing, and wholesaling were fans of the convenience of charging business meals. And, of course, in the early days of T&E club cards it was a status factor to simply dash off a signature on a slip, particularly if the lunch took place in a top restaurant.

Expense accounts and credit cards were a boon to restaurants. There were estimates that in the mid-1950s 50% to 80% of meals in high-priced restaurants were “on the company.” Vincent Sardi admitted that a big chunk of his NYC business was made up of men on expense accounts. Peter Canlis, of Seattle’s first-class Canlis Restaurant, said in 1953 that he decided to establish a restaurant there because “a lot of good expense account money wasn’t being spent because there was no place fancy enough to gobble it up – and I was happy to fill the gap.”

But not all restaurateurs were enamored of the cards at first. For one thing, Diners’ charged a 7% fee on transactions. Restaurant owners felt that they spent too long waiting for their payments and that they had to raise prices to make up for the fees, thus punishing cash customers. Some restaurants refused Diners’ Club cards or added surcharges for meals paid with them. The Diners’ Club lowered its transaction fees in 1966.

By 1965 the three biggest T&E cards, Diners’ Club, American Express, and Carte Blanche claimed a total of about 3.15M cardholders, a small fraction of the number of cards starting to be doled out then, often unsolicited, by nationwide bankcards.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

May 28, 2013

Ohio + Tahiti = Kahiki

In the heyday of Polynesian restaurants, the 1960s and 1970s, the business attracted operators because of high profits in rum drinks. Their marketing relied on bar decoration, bartender apparel, drink names, elaborate serving vessels, and imaginative presentation.

The same was true for “Polynesian cuisine.” There could be no such thing as a Polynesian restaurant without fabulously kitschy decor.

Whatever Polynesian cuisine was, it certainly wasn’t what real Polynesians ate past or present. The Kahiki’s reference point was Tahiti. So, what were Tahitians eating in 1961 when the Kahiki opened? According to a geographer, the traditional Tahitian diet consisted of baked fish, breadfruit, and taro, but natives then preferred French baguettes with Australian butter, rice from Madagascar, canned beef from New Zealand, and Canadian canned salmon, all “washed down with generous drinks of Algerian red wine.”

It’s doubtful that Tahitians ate much in the way of Oriental Beef or Tahitian Flambee (flaming ice cream with rum). Not to mention Tossed Green Salads, Eggs Benedict, or Reuben Sandwiches.

It’s doubtful that Tahitians ate much in the way of Oriental Beef or Tahitian Flambee (flaming ice cream with rum). Not to mention Tossed Green Salads, Eggs Benedict, or Reuben Sandwiches.

But people didn’t go to the Kahiki mainly for its food. As an unenthusiastic reviewer wrote in 1975, “If decor is your reason for dining out, the Kahiki in Columbus is the place for you.”

Its drinks, on the other hand, were hard to resist. With three bars on the ground floor alone, the Kahiki’s menu at one point illustrated drinks served in 30 different glasses, goblets, and ceramic cups and bowls. The most expensive was the Mystery Drink served with four straws. Its presentation involved a scantily dressed server, a gong, a lei, and a kiss. There were also Smoking Eruptions, with fumes emanating from chunks of dry ice, as well as Pago Passages, Malayan Mists, Tonga Tales, and Native Nectars.

Beyond rum, customers were dazzled by the restaurant’s architecture, decor, and theatricality (e.g., periodic thunder and lightning). In the restaurant’s last decades its fans celebrated it as a temple of kitsch but, surprisingly, in earlier years it was often regarded as authentic.

Beyond rum, customers were dazzled by the restaurant’s architecture, decor, and theatricality (e.g., periodic thunder and lightning). In the restaurant’s last decades its fans celebrated it as a temple of kitsch but, surprisingly, in earlier years it was often regarded as authentic.

The building reportedly cost $1 million to build in 1960 and, with 560 seats, was the largest Polynesian restaurant in the U.S. In a flat landscape peppered with indifferent utilitarian structures, it was a startling sight that promised relief from drab ordinariness. Stepping beyond the up-swooping 50-foot facade the visitor entered a darkened Tahitian village with tall palm trees, waterfalls, thatched huts, idols, and a wild profusion of South Seas-style artifacts.

The Kahiki’s decorator, artist and engineer Coburn Morgan, was a prominent Ohio restaurant designer whose career may have been launched by his work on the Kahiki. The flamboyant design of the Kahiki was undoubtedly due to him.

In 1960, when he drew the sketch shown above, Morgan was head of the design division of the Tectum Corporation which furnished many of the composite building materials used in the construction of the Kahiki, including pressed wood for roof supports as well as for soundproofing and decorative wall panels. It may also have been used for flooring and for the stylized fish arrayed along the roof’s crest.

Following completion of the Kahiki, Morgan designed the Aztec-themed Thunderbird Restaurant (Lima), a red-fronted prototype for the Bob Evans chain (Chillicothe), McGarvey’s Nautical Restaurant (Vermillion), the Wine Cellar (Columbus), Jack Bowman’s Steak House (Columbus), the Brown Derby (Columbus), the 18th-century-themed Old Market House Inn (Zanesville), the Tangier Restaurant (Akron — pictured), Mawby’s (Cleveland), and the “Western Victorian-style” Judd’s (Cleveland).

Following completion of the Kahiki, Morgan designed the Aztec-themed Thunderbird Restaurant (Lima), a red-fronted prototype for the Bob Evans chain (Chillicothe), McGarvey’s Nautical Restaurant (Vermillion), the Wine Cellar (Columbus), Jack Bowman’s Steak House (Columbus), the Brown Derby (Columbus), the 18th-century-themed Old Market House Inn (Zanesville), the Tangier Restaurant (Akron — pictured), Mawby’s (Cleveland), and the “Western Victorian-style” Judd’s (Cleveland).

For theme-restaurant inspiration, Morgan traveled to the American West for the Bob Evans chain and to Lebanon for the Tangier, which was modeled on the summer palace of the head of state. The Wine Cellar, owned by Kahiki creators Bill Sapp and Lee (Leland) Henry, had a Shakespeare theme. When it failed in 1991 “16 tall carved knight’s chairs” and a “grand piano bar with winged dragon” were among the furnishings auctioned.

During its more than 50-year run the Kahiki, which was also a nightclub and banquet center, entertained hundreds of thousands of individuals and groups such as Jaycee-ettes, senior citizens, anniversary and wedding parties, and so on. Despite its listing on the National Register of Historic Places and the efforts of local preservationists who felt the Kahiki was an important part of Columbus’ cultural identity, it was demolished in 2000.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

May 19, 2013

Find of the day: the Redwood Room

Sometimes after a day of largely fruitless hunting in the antiques marketplace – such as a recent trip to the Brimfield flea market – it takes a while to realize I’ve acquired a gem. In this case it is the above postcard of the Redwood Room in San Francisco’s Clift Hotel, ca. 1965.

I bought it because it has features that I like: diners, a chef, paneling, and red carpeting. From looking at thousands of images I’ve learned that the last two signify Beef, Money, and Masculinity. But it wasn’t until I read the back of the card that I realized it was a “find.”

On the back is the printed message: “The Redwood Room is unexcelled for fine dining. With its huge panels of 2000-year-old Redwood and the spacious bar, it conveys a feeling of masculinity that has for years appealed to leading San Francisco executives and their wives.”

Little did the people on the postcard know, but “barbarians” were about to descend on the Redwood Room.

The hotel opened around 1916 and the Redwood Room and the French Room (shown through the doorway) were created during the 1930s. Both served the same food, but the hyper-manly Redwood Room was also outfitted with a long redwood bar not shown on the card.

Craig Claiborne visited the Clift in 1964, and declared it was one of the few U.S. hotels that still maintained a kitchen of “relative eminence.” Its decor, he said, was of “undeniable elegance” and its tuxedoed waiters exhibited “politesse.” The menu specialty, as might be expected from a restaurant that borrowed dinner carts from London’s Simpson’s, was “absolute first rank” roast beef accompanied by Yorkshire pudding ($4.50).

The postcard photograph was taken when the hotel was at its peak, prior to a slump in the early 1970s brought on by a poor economy aggravated by a policy of turning away guests who violated the hotel’s conservative dress and hairstyle code. When Burt Lancaster and his longhaired son were refused admittance to the Redwood Room in 1971, the item made newspapers across the nation.

The Clift’s president, Robert Stewart Odell, created the dress code. When the musical “Hair” opened at the nearby Geary Theatre in 1968, “They came in from the theater, barefoot and bareback. For a time . . . the Redwood Room entrance was the scene of an almost daily confrontation between longhairs and the maitre d’hotel,” said a manager. The hotel posted signs and ran advertisements that advised: “The Clift Hotel caters to a conservative, well-groomed clientele. Registration, dining room and bar service is refused to anyone in extreme or abnormal dress and to men with unconventional hair styling.”

In response to the hotel’s conservatism, San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen ridiculed it relentlessly, claiming it maintained “standards set in the Coolidge era as opposed to the Cool era.”

After Odell’s death in 1973, the hotel’s new president (whose hair was longish) welcomed well-dressed stockbrokers, lawyers, and businessmen with hair descending below their collar tops, along with women in pantsuits.

In 1976 the Clift was renamed the Four Seasons-Clift after its acquisition by Toronto’s Four Seasons Hotels, Ltd. After almost two years of remodeling and restoration, the Redwood Room became a bar only rather than a bar and restaurant. Yet it was little changed as that would have brought howls of protest from San Franciscans. A 2001 re-do brought the by-then-shabby Redwood Room bar back into fashionability.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013