Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 37

October 9, 2013

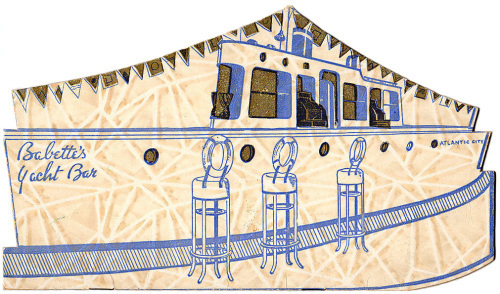

Image gallery: dinner “on board”

There are numerous historical links between restaurants on land and vessels that navigate seas, lakes, and rivers. Ocean going sailors arriving in port, for instance, made up a notable fraction of early restaurant customers. Their ranks also provided stewards, cooks, and chefs, bringing new skills and cuisines wherever they took up their profession on land. San Francisco in the 1850s provides a striking example. In the United States steamboats that traveled the rivers and Great Lakes contained dining salons that were among the 19th century’s most luxurious and among the few places where ornamental French cuisine flourished.

But . . . this post isn’t about that. Instead it illustrates how far restaurants featuring ship and boat themes have strayed from a connection with their watery history. Ship restaurants are for the most part little more than a novelty – but a novelty that can be traced back at least to the 1850s. Despite quite a lot of ship restaurants running aground or sinking, literally and figuratively, there is some kind of primal appeal that keeps them going.

Frank Bazzuro may have been first. He arrived in San Francisco from Italy in 1852 and installed a restaurant in one of the hundreds of ships abandoned in the Bay, introducing his customers to a Genoese fish stew, cioppina. In the 1880s Capt. Paul Boyton, a world-famous swimming champion who popularized rubber wet suits, opened a restaurant on West 29th in NYC called “The Ship” which resembled a ship’s cabin. On Venice Pier in CA, a developer constructed a replica of a Spanish Galleon in 1904, after which it rode the waves of good and bad luck until its demolition in 1946. After an underworld shooting in 1928, it went through a couple of name changes, from Show Boat Café to Volga Boat.

Most ship restaurants that float on water – which not all do – have had checkered pasts as more utilitarian vessels or ones that have spent some time under water. Before it became a floating restaurant in Wilmington NC in 1951, the Ark had transported troops, hosted gamblers, and housed the coast guard. The SS Catala was one of about ten ships that appeared in Elliott Bay during the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle. Previously it had served as a coastal passenger steamship, then fish transporter. When the fair ended it was towed to Los Angeles where it failed as a nightclub restaurant, then appeared in an Perry Mason TV episode before returning to restaurant-ing in Washington where a storm ran it aground.

Dining on a floating restaurant can be hazardous. A storm tore St. Louis’s Becky Thatcher Riverboat from its moorings, sending it downstream where it ran onto the opposite side of the Mississippi in 1969. Bar business was said to be brisk in the interlude before its 100 diners were rescued.

Ships moored on land are safer but rarely very convincing in their roles, particularly if they are in Dallas or Phoenix (below, respectively), smack on a roadway or surrounded by an asphalt parking lot where the water consists of a few puddles.

A parking lot might seem like a strange place for a ship but, a little reflection tells you that Noah’s Ark could have ended up almost anywhere. And that may be the reason enterprises with that name have done business not only on the beach in Leucadia CA, but near the interstate in St. Charles MO (pictured) and in Grovetown GA and Des Moines IA.

Some sites present a real challenge. How do you make your restaurant resemble a ship when it’s in the middle of a block? Boyton’s ship cabin restaurant where only the interior resembles a ship gives an answer, but so do a number of storefronts that have been adorned with protruding ship’s prows, such as Bernstein’s in San Francisco (pictured).

There were oh so many bars shaped like boats and yachts, of which Babette’s was one (above).

There were oh so many bars shaped like boats and yachts, of which Babette’s was one (above).

Many restaurants with ship themes specialize in fish and seafood, but not all. Why not Chinese and American cuisine as in the 1940s Ship Ahoy chain with restaurants in Atlanta and Augusta GA, Charlotte NC, Columbia SC, and Houston TX? Or hamburgers (McDonald’s, St. Louis riverfront, shown below)?

In researching this topic I learned that almost every city or town will sooner or later have a ship restaurant. And many of them will sink, be scrapped, or get towed to another location. The fate of the Showboat Restaurant in Beaverton OR was ironic. In 1981 it became Showboat Liquidators where “Selling Your Boat Is Our Only Business!”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

October 1, 2013

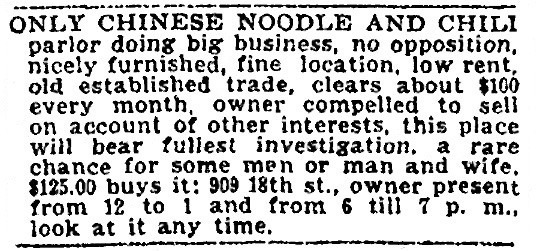

The case of the mysterious chili parlor

Historical research sometimes goes nowhere. I saw the following advertisement in a 1903 Denver newspaper and was intrigued. Chinese noodle and chili parlor? Another strike at the idea of ethnic authenticity in cuisine. I wondered, was the owner Chinese or Mexican or neither? What did “no opposition” mean? I hoped I could find out more.

The ad says “old established trade.” I was unable to verify that. I discovered that in 1890 a man named Reuben Newhart ran a restaurant at 909 18th street, but I could find nothing about him. In the early part of 1902 a restaurant at that address was under the management of Mrs. Lizzie Albin. She also proved to be a cipher. Otherwise Denver city directories for the intervening years showed no restaurants at #909.

I searched for additional advertisements. What I found made everything more confusing.

Can you, dear reader, create a scenario which explains the following series of advertisements?

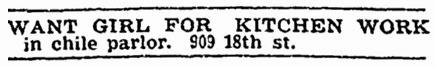

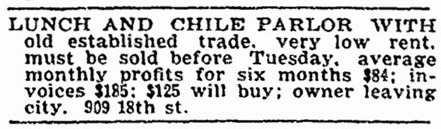

The earliest I found was September 15, 1902, when the business is described as a chile parlor. (Note: chile was often used instead of chili.)

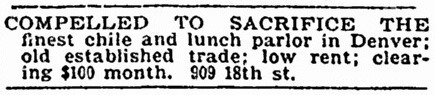

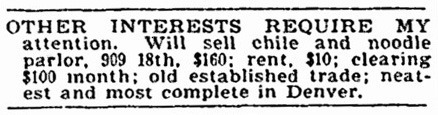

In October it is put up for sale. Clearing $100 a month, about $6,000 today – not too bad for a chili parlor.

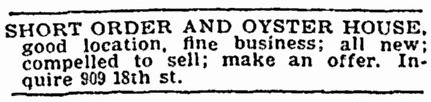

October 24, it is no longer described as a chile parlor but as an “all new” Short Order and Oyster House.

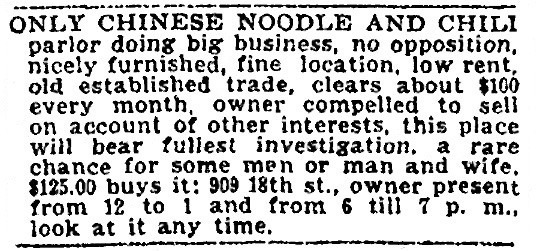

It is on November 19, 1902, that the restaurant is first described as a “chile and noodle parlor.”

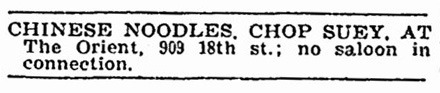

But on December 13 it is doing business as “The Orient” and serving Chinese Noodles and Chop Suey. Western Chinese restaurants were often located in the rear of saloons but, the advertisement announces, this is not true of The Orient. Now we discover the asking price: $160.

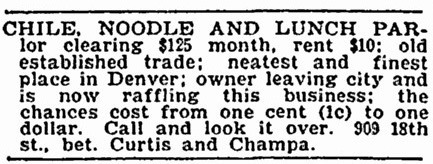

Eight days later, December 21, and the Chile, Noodle and Lunch Parlor is clearing $125 a month. But is that true? The owner must be pretty desperate to sell if s/he is willing to raffle it at 1 cent a chance.

Well, it’s January 25, 1903, and evidently the raffle was not successful. The owner must sell in the next few days. The profit picture seems to have dimmed a little – but maybe the new owner could collect on those invoices, which I’m guessing had been figured into previous profit estimates. Price dropped to $125.

The advertisement that got me interested in the first place, January 28, 1903. Why is no one buying it if it’s doing big business and has a fine location and low rent? The owner isn’t around much.

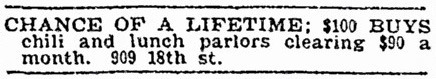

Six days later, the price drops to $100, but now the place is clearing only $90 a month.

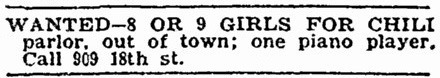

March 11, 1903. Makes no sense at all.

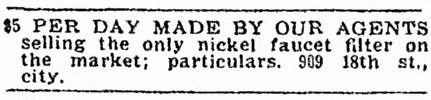

Chile parlor gone! Looks like selling faucet filters is a better deal.

September 24, 2013

Taste of a decade: 1970s restaurants

In the 1970s the restaurant industry and the custom of eating in restaurants grew rapidly. The decade was the gateway to the present in many ways. Despite economic woes (recession and inflation), the energy crisis, urban decline, crime, and escalating restaurant prices, restaurant-going continued to rise.

In the 1970s the restaurant industry and the custom of eating in restaurants grew rapidly. The decade was the gateway to the present in many ways. Despite economic woes (recession and inflation), the energy crisis, urban decline, crime, and escalating restaurant prices, restaurant-going continued to rise.

The president of the National Restaurant Association proclaimed “Dining out is a significant part of the lifestyle of this great country,” noting in 1976 that one out of three meals was being consumed outside the home.

Restaurant patronage was encouraged by all kinds of things, including relaxed liquor laws in formerly dry states and counties, which brought more restaurants into the suburbs, the spread of credit cards, more working wives and mothers, youth culture, and a me-generation quest for diversion.

New York exemplified the problems faced by restaurants in troubled inner cities. Fear of crime kept people from going out to dinner. Restaurants closed, few new ones opened, and cash-strapped survivors began to trade vouchers for heavily discounted meals for advertising. But as New York struggled, California experienced a culinary renaissance as did other parts of the country. Still, much of the U.S. wanted only steak and potatoes, and hamburger was the most often ordered menu item nationwide.

A number of restaurant formats and concepts faced senescence, but new ones came on the scene at a rapid pace. Going, going, or gone were automats, coffee shops, continental cuisine, diners, drive-ins, formal dining, Jewish dairy restaurants, and Polynesian restaurants, not to mention the rule of elite French cuisine.

Fast-food chains continued to grow, with the number of companies increasing by about two-thirds. Growth was especially strong in the Midwest which was targeted as a region susceptible to their appeal. Toledo was bestowed with Hardee’s, Perkins Pancakes, a Mexican chain, and, in 1972, the arrival of two Bob Evans eateries. Another Ohio city, Columbus, was christened a test market for new fast-fooderies while Junction City KS, bordering Fort Riley, looked like a franchiser’s fast food heaven. By contrast, greater Boston had only one Burger King and one McDonald’s in 1970.

Along with the chains and a shortage of (cheap) kitchen help, came an upsurge in restaurants’ use of convenience foods and microwaves. In response, municipalities across the country enacted ordinances to protect consumers against false claims on menus, many of them centering on misuse of the words “fresh” and “home-made.”

Along with the chains and a shortage of (cheap) kitchen help, came an upsurge in restaurants’ use of convenience foods and microwaves. In response, municipalities across the country enacted ordinances to protect consumers against false claims on menus, many of them centering on misuse of the words “fresh” and “home-made.”

Yet as the country was swamped with fast food, it experienced the flowering of restaurants specializing in ethnic, artisanal, and natural foods. Hippie and feminist restaurants stressed honest, peasant-style meals. Burgeoning interest in nutrition made salad bars popular. Bean sprouts, zucchini, and more fish showed up on menus. Diners learned that Chinese food was not limited to Cantonese, but might also be Mandarin, Szechuan, or Hunan. Once languishing behind luxurious decor, impeccable service, and famous patrons, food took center stage in deluxe restaurants as they purged Beef Wellington from their repertoire and took up the call for culinary creativity and authenticity.

Though not unknown in earlier decades, the restaurant-as-entertainment-venue came into full flourish with the proliferation of theme restaurants with unbearably cute names such as Orville Bean’s Flying Machine & Fixit Shop. To supplement a shrinking supply of old stained glass windows, telephone booths, and barber chairs, restaurant fixture companies began to manufacture reproduction antiques.

However crazy and mixed up the foodscape, America had become the land of restaurants for every taste and pocketbook.

Highlights

1971 – In Berkeley CA Alice Waters and friends found Chez Panisse, marking the movement of college and graduate students into the restaurant field, a career choice which is beginning to have cachet.

1971 – In Berkeley CA Alice Waters and friends found Chez Panisse, marking the movement of college and graduate students into the restaurant field, a career choice which is beginning to have cachet.

1972 – NYC’s Le Pavillon, considered the finest French restaurant in the U.S., closes. In Kansas City MO the first Houlihan’s Old Place, adorned with nostalgia-inducing decorative touches, opens, as does Mollie Katzen’s natural-food Moosewood Restaurant in Ithaca NY.

1972 –Dry since 1855, Evanston IL, home of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, grants liquor licenses to two hotels and six restaurants. Their business doubles in a few months.

1973 – Los Angeles County becomes the first jurisdiction in the country to enact a “truth in menu” ordinance. During the pilot program, the scenic Sea Lion Restaurant in Malibu is caught selling the same fish under five different names with five different prices.

1974 – A Chicago food writer throws cold water on arguments about which restaurant has the best lasagne, asserting that the debaters “might have found that same lasagne in restaurants all over the country” courtesy of Invisible Chef, Armour, or Campbell’s.

1974 – Restaurateur Vincent Sardi spearheads a campaign to get New Yorkers to eat out, claiming that the city’s major restaurants have lost up to 20% of their business in the past two years, thus precipitating the closure of 20 leading restaurants.

1976 – The CEO of restaurant supplier Rykoff says whereas his company once supplied whole tomatoes it now provides diced tomatoes “because the operator just can’t afford to pay someone to cut them up.”

1976 – Richard Melman’s Chicago restaurant company, Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, operator of RJ Grunts, Great Gritzbe’s Flying Food Show, and Jonathan Livingston Seafood, opens Lawrence of Oregano and prepares to take over the flamboyant Pump Room.

1976 – Richard Melman’s Chicago restaurant company, Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, operator of RJ Grunts, Great Gritzbe’s Flying Food Show, and Jonathan Livingston Seafood, opens Lawrence of Oregano and prepares to take over the flamboyant Pump Room.

1977 –Industry journal Restaurant Business publishes survey results showing that, on average, husband & wife pairs eat out twice a month, spend $14.75 plus tip, prefer casual restaurants, and tend to order before-dinner cocktails and dishes they don’t get at home. Measured by sales, Lincoln NE is one of the country’s leading cities for eating out.

1977 – Once characterized by blandness, San Diego now has restaurants specializing in cuisines from around the globe, an improvement one observer attributes in part to the new aerospace industry there.

1978 – A reviewer in Columbia MO complains, “A brick floor and pillars, old photos, Tiffany lamps, stained-glass windows and trim on the tops of the booths as well as revolving single-bladed, old-fashioned fans [is] a familiar type of decoration these days and I’m getting a little weary of the sameness of so many restaurants.”

1979 – As the year ends restaurant reviewer Phyllis Richman observes that more people are eating out than ever before, transforming once-lackluster Washington D.C. into “what is known as a Restaurant Town.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

September 16, 2013

Picky eaters: Helen and Warren

Helen and Warren liked eating in restaurants in the early 20th century when it was a rare experience for most Americans. They kept up with the trends and they tried restaurants of every format. They were affluent New Yorkers, somewhat jaded and always seeking the new thing.

Helen wanted to avoid expense and ostentation but was uncomfortable in offbeat places. Warren was cynical and alternately a cheapskate or big-spender. Both were distrustful. They feared they’d be taken advantage of, and sometimes were.

In the 1920s Helen and Warren were the best known couple in the U.S.A.

But they were fictional. They were the creation of Mabel Herbert Urner who wrote a column about the pair for over thirty years, from 1910 until the early 1940s. The column was widely syndicated in newspapers from Boston to Los Angeles as well as in Canada and England. Though fiction, the column presents a fascinating subjective view of dining out, particularly in the 1910s and 1920s.

Helen’s and Warren’s experiences likely had some resemblance to Mabel’s own life, particularly when the couple visited restaurants in Paris, London, and other European capitals. After marrying rare book dealer and collector Lathrop Colgate Harper in 1912, Mabel traveled with him around the world. In New York they lived in an apartment at 1 Lexington Avenue across from Gramercy Park from which they surely forayed into restaurants regularly.

Helen’s and Warren’s experiences likely had some resemblance to Mabel’s own life, particularly when the couple visited restaurants in Paris, London, and other European capitals. After marrying rare book dealer and collector Lathrop Colgate Harper in 1912, Mabel traveled with him around the world. In New York they lived in an apartment at 1 Lexington Avenue across from Gramercy Park from which they surely forayed into restaurants regularly.

Did Mabel and Lathrop, like her famous pair, have a preference for out-of-the-way restaurants such as the French and Italian tables d’hôtes in NYC? One starlit summer night in 1913 Helen dragged Warren to a backyard café run by three sisters. Helen exclaimed “Why, it’s a bit of Paris!” when she stepped into the garden. They were surrounded by writers, artists, and illustrators, including a “queerly dressed” literary woman. (Mabel’s inside joke?) Warren, a successful businessman, scoffed at the artists but even he had to admit afterward, “That [was] the best dinner in New York for the money.” They paid 65 cents each for soup, beef tongue with piquant sauce, squab, and salad, finished with fresh pears, Camembert, and coffee – wine included. The café was clearly modeled on that run by the Petitpas sisters on W. 29th in conjunction with a boarding house where artist John Butler Yeats lived. A dinner with Yeats and friends about this time was memorialized in a painting by John Sloan.

The Petitpas dinner was one of the couple’s few positive experiences. As much as Helen was drawn to offbeat restaurants, she was often squeamish about unsanitary conditions. She refused to eat ground meat. Usually she wiped her silverware with her napkin. She had problems in a Chinese restaurant, an Italian place, an “anarchist restaurant,” probably Maria’s, as well as at the Pink Parrot in Greenwich Village (probably the Pepper Pot, shown here). When she pushed away her plate there, Warren reprimanded her, saying, “You’re a bum bohemian.”

Helen and Warren visited cafeterias, tea rooms, pre-war cabarets, hotel dining rooms, roadhouses, and shoreline resorts in the NYC metro area. Helen was often embarrassed by Warren’s behavior when he showed off or spent too much money. They bickered. He declared a tea room she liked “a sucker joint.” She was critical of the decor and pomp of expensive restaurants, but her attempts to put a brake on Warren’s spending often backfired.

In 1913 they went to a restaurant in the throes of a waiters’ strike. Somewhat surprisingly, considering the bourgeois lifestyles of both Mabel and Helen, the story presents a case for the strikers. Helen questions their server about the goals of the strike, and he says, “They want decent food, m’am; clean food and a clean place to eat it. They want to be treated like men – not dogs! And they want a living wage.” Warren asks about tips and the waiter replies, “Why does he have to depend on tips thrown at him?”

In many ways Helen’s and Warren’s restaurant adventures and complaints seem relevant today. Has it happened to you that a server tries to remove your meal in progress? Have you been charged extra for bread? Welcome to the 1910s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

September 9, 2013

Hot chocolate at Barr’s

Even in a good-sized, prosperous city as Springfield MA was in the late 19th century, a chance to sit down and be served a cup of hot chocolate or other refreshments was hard to come by. Other than hotel dining rooms, usually open only during mealtimes, there was just about nothing.

Except for the city’s leading confectioner. As was true in other cities, a confectionery restaurant assumed a prominent role in feeding and entertaining the public.

E. C. Barr & Co. was Springfield’s leading restaurant, caterer, candy and ice cream maker, and baker of fine pastries and wedding cakes. In an advertisement in December 1889 it advised, “Ladies while on your Holiday shopping tour try a cup of that hot Chocolate, Cocoa or Bouillon at BARR’S Restaurant.” For most of its long existence it did business on Main Street, for 20 years occupying a corner just across from the city’s foremost retailer, the Forbes & Wallace department store.

Barr’s reach went beyond Springfield. With a branch in Northampton, its fame was known throughout Western Massachusetts. The restaurant ran advertisements in Amherst to lure students from the Massachusetts Agricultural College to come out for a “spread” or a class dinner. This 1884 example ran in the M.A.C.’s yearbook.

Barr’s reach went beyond Springfield. With a branch in Northampton, its fame was known throughout Western Massachusetts. The restaurant ran advertisements in Amherst to lure students from the Massachusetts Agricultural College to come out for a “spread” or a class dinner. This 1884 example ran in the M.A.C.’s yearbook.

Barr’s stayed in the public eye as a prime banquet venue and with elaborate show window displays of confectionery. In 1909 the company commemorated the exploration of the North Pole with representations of Cook and Peary and their exploring party, all made of sugar fashioned by owner Edwin Barr’s son Walter.

Recently I was lucky to find the postcard image of the Japanese Tea Room in the Barr restaurant shown above. It dates from about 1906, when a dessert called the Priscilla College Ice, an ice cream soda with a “totally different flavor,” was a popular order. Edwin Barr’s second wife, Minerva, worked with him and it’s likely she supervised the tea room and may have chosen the Japanese theme which was in vogue then.

Barr’s was begun in 1865 or 1866 when founder Edwin Barr finally decided to give up prospecting for gold in California and Montana and returned to Springfield to settle down. It wasn’t until around 1891 that Edwin acquired the Main and Vernon corner (384 Main), one of the most valuable corners in the city’s shopping district. (It’s likely that the 884 Main address on the trade card shown here is misprinted.)

In 1870 an article in the Springfield Republican claimed that Barr’s decor was more “tasteful” than that of Delmonico’s in New York. Keep in mind that the New England taste of that time leaned toward plainness. The story also praised the appearance of the restaurant’s menu which was printed on cream paper with a thin magenta border – “neat, but not gaudy.”

Sadly the Barr family’s lives were not so neat. In 1891 Edwin’s eldest son, George, who managed the family’s Hotel Warwick in Springfield, shot and killed his wife and himself in a fit of jealousy. Edwin’s third son, Jesse, manager of the Northampton restaurant, died of syphilis in 1900.

Fortunately Edwin’s son Edgar lived a long life and carried on his father’s business for a time after Edwin’s death in 1911. In 1912 the restaurant moved to East Bridge Street and later was recreated on State Street. I have not been able to discover how long it remained in business.

Clearly Barr’s glory days were at Main and Vernon. That site underwent many demolitions, the latest being construction of the Monarch Place hotel and office complex.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

September 2, 2013

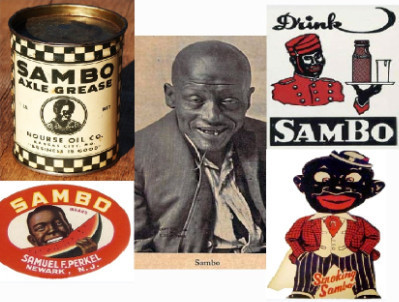

Name trouble: Sambo’s

You might imagine that chain restaurants would spend vast amounts of time and money researching potential names in order to pick one that would convey exactly the desired associations and nuances. Certainly one that would not insult a portion of its intended customers.

I’m sure most do. Sambo’s was not among them.

Wouldn’t the founders of Sambo’s, in the late 1950s, dimly perceive that the name Sambo was not beloved by everyone, especially African-Americans?

Why would they decorate with images from the book “Little Black Sambo,” the American editions of which were filled with racist caricatures?

Evidently they had no idea that Sambo had been – and still was – a derogatory word for black males for over 100 years; that the name and ridiculous images of Sambo were used on many consumer products in the early 20th century; and that after WWII school libraries had complied with requests by African-Americans to remove the book from shelves.

Even if they didn’t know any of this, when protests erupted they might have realized they had made a terrible mistake. Regardless of whether “Sam-bo” originated from the first name of one of them combined with the nickname of the other.

Nope, nope, nope, and double nope.

Instead the founders, their successor, and the corporation that finally took over the chain all insisted right up to the bitter end that no harm was intended or implied. Even as they renamed some units in the East where there had been boycotts, the company insisted the change was purely in order to market their new menus.

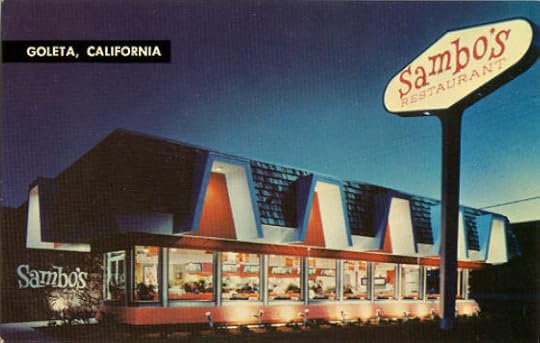

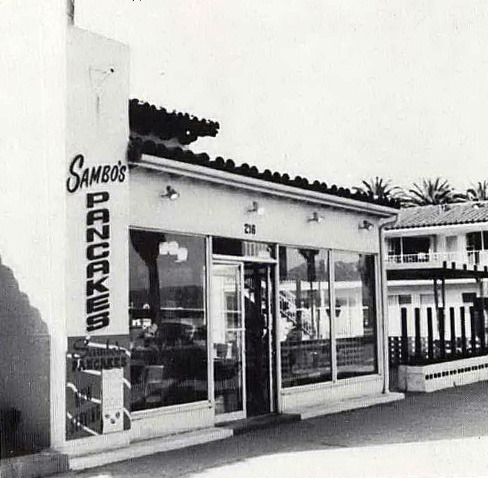

The first Sambo’s was opened in Santa Barbara in 1957. [pictured] By 1977, when the son of one of the founders was heading the company, the chain was the country’s largest full-service restaurant chain, with 1,117 units.

The first Sambo’s was opened in Santa Barbara in 1957. [pictured] By 1977, when the son of one of the founders was heading the company, the chain was the country’s largest full-service restaurant chain, with 1,117 units.

But trouble was looming. Protests during the West Coast chain’s expansion into the Northeast had already resulted in renaming units in the Albany NY area “Jolly Tiger.” Eventually there were 13 Jolly Tigers in various towns. Protest would spread to Reston VA, New York, and New England including at least 9 towns in Massachusetts. In 1981 the Rhode Island Commission on Human Rights ordered the company to change its name in that state because indirectly the name violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act by denying public accommodations to black persons.

The company responded that it would rename 18 of its Northeastern units “No Place Like Sam’s”; in fact according to an advertisement a few months later they actually renamed 41 units.

The company responded that it would rename 18 of its Northeastern units “No Place Like Sam’s”; in fact according to an advertisement a few months later they actually renamed 41 units.

Soon thereafter the company began to collapse. In November 1981 it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, closing more than a third of its units. In Leominster and Stoughton MA, early morning customers had to pick up and get out immediately so the restaurants could be padlocked.

In 1982 all, or most, remaining Sambo’s were renamed Seasons. By 1984 most of the Seasons restaurants had been sold to Godfather’s Pizza and other buyers.

The successive name switches undoubtedly hurt business, but a more serious problem was that Sambo’s, like other chains using a coffee shop format with table service and extensive menus, had been steadily losing out to fast food chains.

The chain is kaput yet the beat goes on. The original Sambo’s in Santa Barbara continues in business under new ownership – still using the thoroughly discredited name. On its website it also continues the threadbare tradition of justifying the name as a compound of the founders’ names.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

August 26, 2013

“Eat and get gas”

When I first encountered that jokey phrase as a child I thought it was amazingly clever and funny. So did many adults, evidently, because over the decades numbers of roadside eateries adopted it as a catchphrase. Even as late as 1976 Stuckey’s was using it on a billboard near Dallas. A roadside gas station/café outside Omaha bore the equally cornball name Tank and Tummy.

It wasn’t long after thousands of Americans acquired cars and took to the roads in the 1920s that all kinds of roadside businesses popped up to serve them. They ranged from campgrounds in farm fields to tourist homes and cabins, gas stations, tea rooms, and cafés. The Depression failed to stifle the urge to travel by car while inspiring thousands to try to make a living from passing traffic. Among the ideas included in a dispiriting little 1937 pamphlet called The Roadman’s Guide (“A Valuable Book of Money Making Formulas, Recipes, Ways, Plans and Schemes”) were carnival games, refreshment stands, and “eating joints.”

The gas station/restaurant combination was a popular one, often further combined with a gift shop or rooms for overnight guests. The logic is the same one-stop-shopping idea used by department stores: get customers to stop in for essentials and they may buy other things they didn’t even know they wanted. In Taunton MA in the 1920s, the Marvel Lunch and Filling Station not only had chicken and duck sandwiches on offer but also advertised “Stop and See the Trained Bears.”

Although it did tend to render them less refined, some tea rooms were linked to gas stations. Yet Duncan Hines’ 1937 edition of Adventures in Good Eating for the Discriminating Motorist gave a slightly grudging nod to The Old Elm Tree near Fremont OH, indicating “Just a wayside place with filling station adjacent but they serve a mighty good steak and chicken dinner, as well as all kinds of sandwiches and salads.”

Among those who tried combining gas and eating in the Depression – and succeeded – were Harlan Sanders and Gus Belt, respectively founders of Kentucky Fried Chicken and Steak ’n’ Shake.

Which came first in these combined ventures — the gas station or the restaurant? I’ve decided that in most cases it was – and still is – the gas station. And that might account for why so few roadside dining spots earn a reputation for fine food. Consider chains such as Stuckey’s, Nickerson Farms, and Dutch Pantry.

With superhighway construction in the 1950s and 1960s, highway stops institutionalized paired restaurants and gas stations, though by this time they were housed in separate buildings. In 1961 the Stouffer Corporation teamed up with Standard Oil of Ohio to test automat-style restaurants. They were not a success, but generally highway self-service food courts have proved acceptable to the motoring public.

Like many of the eat-and-get-gas highway oases before them, interstate service plazas also do duty as truck stops. But that is the subject of a future post.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

August 15, 2013

The fifteen minutes of Rabelais

Watch me wipe that smile off his face.

François Rabelais was a French writer, an eccentric, and a joker who lived centuries ago. Based on a prank he pulled to get out of paying a dinner bill, the phrase “quarter hour of Rabelais” has come down through history to refer to the unhappy time when diners are confronted with the bill for their restaurant meal.

Personally, I am someone who always has a rough estimate of what I’ll have to pay at the end, so I am scarcely in the same boat as Rabelais. All the more so because I definitely would not go into a restaurant (in his case, an inn) and order a meal knowing I had no money.

But, it is a well known fact that some people order freely – and drink freely – to the point that they have no idea what their total bill will come to. And, in the olden days, there was no written menu so it wasn’t always clear what everything cost.

According to lore, Rabelais was penniless yet ate and drank as though there would be no reckoning. When the bill came, he held up a flask and announced he planned to poison the king with its contents. He was arrested and carried off to the palace. The king took the whole incident as a big joke. An unlikely story if I ever heard one.

Nevertheless the phrase survived and is, or was, well known in France as a moment of letdown when you realize you’ve got to pay the bill. Maybe in modern times credit cards have distanced us from that feeling. Or, is it simply that not that many people sit around restaurant tables drinking all night anymore?

Obviously misery about paying the bill is worsened if the diner is short of money. Or if his or her companions have departed without leaving enough money for their shares – something that can still be counted on to happen from time to time. Perhaps that is a modern example of the “quart d’heure de Rabelais” as it was memorialized in the following bad poetry from 1887.

The question of who pays is an associated issue. Though it isn’t well known, the law considers everyone at the table responsible for the check. If there are four and three leave, and all the orders are on one check, the last person remaining must pay the total bill.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

August 8, 2013

Image gallery: shacks, huts, and shanties

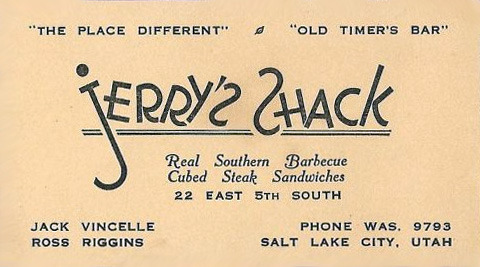

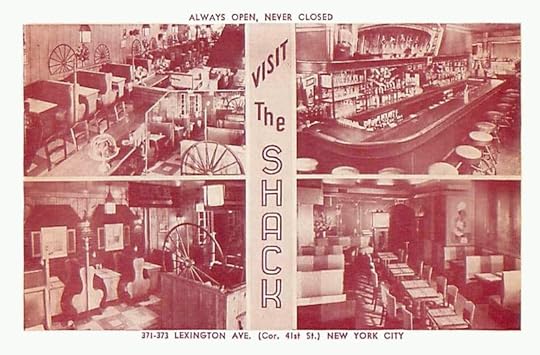

Like stands, shacks most certainly represent a type of eating places whose origins stretch back into antiquity. Their simple structures can be erected hastily for fairs or to capture the pennies of hungry travelers. In an automobile culture they suggest open spaces and open roads.

Like stands, shacks most certainly represent a type of eating places whose origins stretch back into antiquity. Their simple structures can be erected hastily for fairs or to capture the pennies of hungry travelers. In an automobile culture they suggest open spaces and open roads.

They convey honest rusticity with uncomplicated, inexpensive fare for ordinary folks rather than elaborate cuisine accompanied by the pomp and ceremony of the palace as enshrined in posh restaurants. The kinds of food sold in shacks, huts, and shanties is likely to be lobster, fried chicken, barbecue, or other casual fare that is eaten with the hands, and quickly.

Low prices are implied in huts and shacks. The slogan of the Shack in Upper Darby PA was “Where Dining is an Event not an Extravagance,” while New York City’s eighteen Shanties of the 1930s promised “The Country’s Finest Products at the City’s Lowest Prices.” For 15 cents the menu offered orange or tomato juice, buttered toast, and coffee.

Low prices are implied in huts and shacks. The slogan of the Shack in Upper Darby PA was “Where Dining is an Event not an Extravagance,” while New York City’s eighteen Shanties of the 1930s promised “The Country’s Finest Products at the City’s Lowest Prices.” For 15 cents the menu offered orange or tomato juice, buttered toast, and coffee.

On the other hand, low prices or not, how many people would want to patronize a true shack? The crude Depression-era lunchroom shown above has a tarpaper roof and scanty stock on its display shelves.

Today, because such places are harder to find, they project a strong contrast with the manufactured food and decor of chain restaurants. In contrast with artless roadside shanties, McDonald’s and other fast-food outlets are carefully designed, highly managed food selling environments.

Today, because such places are harder to find, they project a strong contrast with the manufactured food and decor of chain restaurants. In contrast with artless roadside shanties, McDonald’s and other fast-food outlets are carefully designed, highly managed food selling environments.

At the same time, restaurants tend to look to the past rather than the future for themes that will attract customers. Shacks and huts are entirely capable of filling that role too, even in New York City, a most unlikely setting. The Shack, in Manhattan, is scarcely convincing. One of Chicago’s leading restaurants of the 1930s was the Chicken Shack, which was furnished with not-a-bit-rustic modernistic chrome tables and chairs. Its proprietor, Ernie Henderson, was invited to demonstrate his chicken frying methods at the 1939 convention of the National Restaurant Association, marking the first time an African-American was given such an opportunity.

At the same time, restaurants tend to look to the past rather than the future for themes that will attract customers. Shacks and huts are entirely capable of filling that role too, even in New York City, a most unlikely setting. The Shack, in Manhattan, is scarcely convincing. One of Chicago’s leading restaurants of the 1930s was the Chicken Shack, which was furnished with not-a-bit-rustic modernistic chrome tables and chairs. Its proprietor, Ernie Henderson, was invited to demonstrate his chicken frying methods at the 1939 convention of the National Restaurant Association, marking the first time an African-American was given such an opportunity.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

July 31, 2013

What would a nickel buy?

At a self-service restaurant in the town where I live, the menu includes a simple dish of beans and rice for only $1.25. It’s not steak but it’s better than a candy bar for anyone who is hungry but short of money.

It’s interesting to see typical restaurant prices from the past and to try to figure out if their prices were low or high. I remembered running across old advertisements for 5-cent dishes which I estimate might equal the $1.25 rice and beans of today. What, I wondered, did 5 cents buy in lunch rooms and restaurants of the past?

1869 – One quarter of a pie costs 5 cents in cheap and lowly New York City restaurants. (Five cents then would equal 87 cents today.)

1878 – Boston’s saloon eateries charge 5 cents for a schooner of beer. In some places the beer entitles the purchaser to free cheese and crackers. (Five cents then would equal $1.25 today.)

1880s – At the Old Albany Oyster & Eating House, patrons can take their choice of vegetable soup, meat stew, 1 dish of pickles, 4 slices of bread, or 1 dish of butter, each for a nickel.

1880s – Visitors to the circus in Hartford CT can get a meal very cheaply [see menu], just as they can at Frank’s Dining Rooms in Boston [see above].

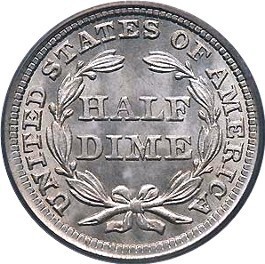

1890 – At the Half-Dime Lunch in Springfield MA, as in Hartford, every dish costs only a nickel. Half dimes were replaced by nickels in 1866 and are suggestive of the olden days.

1890 – At the Half-Dime Lunch in Springfield MA, as in Hartford, every dish costs only a nickel. Half dimes were replaced by nickels in 1866 and are suggestive of the olden days.

1894 – Chicago’s sandwich wagons sell ham and egg sandwiches for 5 cents to patrons who don’t mind eating on the curb. In Worcester, night lunch wagons price all sandwiches at 5 cents except for sardine sandwiches which cost double. (Five cents then would equal $1.38 today.)

1894 – Five cents doesn’t buy much except a little something to eat. A Boston restaurant that covers its walls with folksy signs has one that says, “No napkins served with 5¢ orders. See?”

1905 – Five cents at the J.S. Mill’s Lunch and Sandwich Room in St. Paul MN will buy a sandwich of egg, wienerwurst, cheese, or pigs’ feet. (Five cents then would equal $1.35 today.)

1914 – About 1/4 of drug store soda fountains charge 5 cents for an ice cream soda.

1921 – At Thornton’s Cafeteria in Atlanta, fried oysters are 5 cents apiece. (Five cents then would equal 64 cents today.)

1929 – Following the stock market crash, a roadside stand in Great Falls MT named The Barrels slashes the price of a 10-cent glass of root beer in half.

1950 – The Horn & Hardart Automats finally raise the price of a cup of coffee from 5 to 10 cents. (Five cents then would equal 48 cents today.)

1979 – At a New Jersey surf & turf barn called The Wooden Nickel, nickels are valued only for their nostalgic aura. The Wooden Nickel’s specialty dish costs $12.95.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013