Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1415

June 5, 2014

Asian Leaders Value Creativity and Intuition More than Europeans Do

Do leadership styles differ around the world? This is one of the questions explored by our recent International Business Report. We asked 3,400 business leaders working in 45 economies to tell us how important they believe certain attributes are to good leadership.

Patterns in their responses point to some intriguing cultural differences. While the top traits – integrity, communication, and a positive attitude – are almost universally agreed upon by respondents (and confidence and the ability to inspire also rank high globally) not everyone is aligned on the importance of two other traits: creativity and intuition.

Nine in ten ASEAN leaders believe creativity is important, compared with just 57% in the EU; while 85% of ASEAN leaders think intuition is important, compared to only 54% in the EU. More generally, we find greater proportions of respondents in emerging markets falling into the leadership camp we would call “modernist.” They put more emphasis on intuition and creativity and also place greater value on coaching than leaders who are “traditionalists.”

This is an intriguing discovery, but it immediately raises a follow-on question. It’s conceivable that our survey captured a gap that still exists for now but is shrinking, as globalization brings a certain sameness to businesses around the world. Will we see a steady convergence in leadership – and toward the Western style – as developing economies mature?

Many believe so. As one example, Harvard Business School’s Quinn Mills has made this prediction: “As Asian companies rely more on professional employees of all sorts, and as professional services become more important in Asian economies … Asian leadership will come to more resemble that of the West.”

I’m not so sure. Given the superior growth rates of their economies, it might be that leaders in emerging markets are gaining the confidence to stick with the management approaches that have apparently been working for them – or that they have the agility to adapt to whatever techniques and tone prove best suited to their fast-evolving local markets. A separate Grant Thornton study on Chinese leadership finds that chairmen of companies there are deliberately blending imported and home-grown management techniques and approaches to create a new “Chinese Way” of leading, rather than copying and replacing.

And here is the really big factor in play as leadership styles continue to evolve: Women still have far to come as business leaders. Today, just 24% of senior business roles around the world are held by women, but the proportion of female CEOs is on the rise. Awareness is growing that diversity, of all sorts and in any walk of life, leads to better decisions and outcomes. There is now a wealth of empirical evidence proving that greater gender diversity correlates with higher sales, growth, return on invested capital, and return on equity. One recent study from China even finds that having more women on company boards reduces the incidence of fraud. Meanwhile, uniformity of background often yields uniformity of opinion and worse decisions. The pressure is on to make boardrooms and management ranks less “male and pale.”

It has often been claimed that a key way in which business women differ from business men is in their leadership styles. For example, research shows that women leaders, on average, are more democratic and participative than their male counterparts. Studies have also shown that, as investors, women are more risk-averse and, at the household level, tend to invest a higher proportion of their earnings in their families and communities than men.

Looking across the global landscape today, we find women more prevalent in the upper echelons of companies in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. Perhaps it is not just coincidence that where we see more women leading, our survey finds more openness to using creativity and intuition – and also a higher value placed on the ability to delegate. In any case, these parts of the world, with their higher proportions of women in leadership, have a fair claim to be arriving sooner at the well-blended leadership style of the future.

Decision-making based on analytics is all the rage now, and certainly represents progress in many areas where managerial decisions have been made in the past on “gut feel.” But there are still many decisions in business that, either because they relate to future possibilities or because they involve trade-offs of competing values, can’t be reduced to data and calculations. One could argue that those are the very decisions – the ones requiring creativity and intuition – where leadership is most called for and tested. In a fast-moving, digitally-powered world, creativity and intuition could be the difference between gaining ground as an innovator and getting left behind.

June 4, 2014

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

After an unprecedented decade of growth, analysts wrote off 2013 as a year to forget for Apple. Most pundits agreed on what was wrong — a lack of breakthrough innovation since the passing of founder Steve Jobs. But in our view, Apple faces a deeper problem: the industries most susceptible to its unique disruptive formula are just too small to meet its growth needs.

Apple has seemingly served as an anomaly to the theory of disruptive innovation. After all, it grew from $7 billion in 2003 to $171 billion in 2013 by entering established (albeit still-emerging) markets with superior products — something the model suggests is a losing strategy.

Back in 2008, we suggested that the key to Apple’s success was that it had perfected a particular disruptive strategy we dubbed “value chain disruption.” That is, rather than employ a new technology to disrupt a company’s business model, an upstart disrupts the entire breadth of an entrenched value chain by wresting control of a critical asset. Thus Apple’s integration of its iPod device, iTunes software, and iTunes music store disrupted the existing music industry value chain from the record labels to the CD retailers to the MP3 device makers. The key to Apple’s success was that Steve Jobs was able to convince the major record labels to sell its critical asset — individual songs — for 99 cents.

Achieving such a wholesale disruption of an industry is exceeding rare because the key players in the existing value chain typically have controlling rights to the scare resource, which prevents a new value chain from forming. And they are understandably loathe to give it up. But at the time, the music labels were under attack by upstarts giving their offerings away for free and were embroiled in a fairly hopeless effort to sue Napster and other music-sharing services into oblivion. In relation to nothing, 99 cents looked pretty good.

The deal Jobs struck allowed Apple to form a new digital value chain for the legal distribution of music content with itself at its center, reaping high margins on its iPod hardware. Apple quickly became the largest music retailer in the U.S. The record labels grumbled that Apple sucked the lion’s share of the profits out of the industry, but it was too late.

Jobs and Apple were able to run this play again with the introduction of the iPhone. About a decade ago, wireless carriers like AT&T, Verizon, and Sprint tightly controlled the wireless telecom value chain through the critical asset – so-called “walled gardens” they had placed around their service that prevented users from putting any nonauthorized content on their phones.

Jobs made the iPhone’s success possible by negotiating the famous deal in 2007 with the then-struggling AT&T Wireless which, in an effort to distinguish itself from its rival carriers, surrendered control over phone content in exchange for exclusive access to the iPhone in the U.S. for three years. As a result, Apple was once again able to create a new value chain, with the App Store playing a role similar role to the iTunes store, and once again reaping high margins on its hardware.

AT&T’s deal with the devil allowed it to grow substantially, but it started a process that has led wireless carriers to increasingly complain that profits have shifted from them to the device and content producers. Customers now decide first what mobile value chain they will join (Apple or Android), and choose a carrier second.

Today, Apple sits at a crossroads. In our view, the question facing CEO Tim Cook isn’t how Apple will remain “insanely great” without Jobs at the helm. It’s whether there are any other value chains it can disrupt in industries both desperate enough to be vulnerable — and big enough to fuel Apple’s further growth beyond its current $171 billion in annual revenues. After all, even modest 6% growth at this point equates to more than $10 billion in new revenue.

Let’s look at four value chains Apple could disrupt, each of which in markets that, on the face of it, seem large enough to offer hope: television, advertising, health care, and automobiles.

The TV market is immense, and Apple has a toe in the door with its Apple TV, a special purpose device that allows users to stream content from the iTunes library and a select group of partners to existing televisions. But by this time, content owners like Time Warner and cable operators like Comcast have learned from the music and mobile phone industries and won’t cede sufficient control over content to enable Apple to disrupt the entire value chain. So, at the moment Apple TV is a $1 billion line of hardware that is so small, relatively speaking, that Jobs dismissed it as a hobby. What’s more, Apple already has to contend with competing offerings from start-ups like Roku and other tech companies like Google and Amazon, both of which have introduced set-top boxes with streaming content services.

Just as traditional television will be with us for many more years, so will traditional television advertisements. The market looks more than big enough for Apple, and it has made several acquisitions that edge onto the market, including Quattro Wireless (a platform for mobile advertising) for $250 million in 2010. But the critical asset in that value chain is the viewership data that Nielsen provides, which sets the price for advertising. And Nielsen has no reason to cede control of it.

Apple might try to compete with Nielsen directly by offering up a superior metric, such as a measure of audience engagement or a way to track actual transactions generated by a broadcast advertisement. That’s not entirely impossible, given the obvious limitations of Nielsen ratings as a predictor either of audience size or of a commercial’s ability to increase sales. But that approach would take substantial investment, and the fight with entrenched incumbents on their own ground would be fierce.

The delivery of primary health care in the United States is ripe for disruption. Apple might conceivably go beyond what seems to be inevitable forays into the fitness and health-monitoring markets to create new disruptive ways to diagnose and deliver primary care and support the ongoing treatment and management of chronic illness. Doing so would require some nifty regulatory maneuvering. It would also require the company to crack a problem that has flummoxed Google and Microsoft: the creation of a simple, common electronic medical record, which could function as the glue of a new primary care value chain.

IBM with its Watson computer seems to be positioning itself as a vital partner for the world’s most complicated problems, but Apple has a demonstrated history of bringing elegant simplicity to the kinds of everyday problems that serve as the core of primary care. Our view is this is the most complicated of the organic options and therefore the one with the lowest chances of success, but the one that also has the most upside potential.

These first three paths are primarily organic in nature. But what if Apple followed through on rumors that it might acquire Tesla, Elon Musk’s rapidly growing electric vehicle company?

Tesla is clearly attempting to disrupt the automobile value chain by building charging stations and battery factories and challenging independent dealers with direct sales. Perhaps combining with Apple would help Tesla navigate the complicated regulatory challenges facing its deployment. However, rather than leveraging preexisting assets at the center of the sprawling petroleum-powered car value chain to disrupt it, Apple and Tesla would have to invest heavily to create an entirely new one. Apple’s vast assets would certainly help Tesla wage that battle, but the required investments would be gargantuan.

None of these options is a slam dunk, of course. If they all end up being strategic dead ends and Apple can’t find another mega-industry value chain ripe for disruption, perhaps the company needs to consider something more radical. A recent article in The Economist counseled Warren Buffet to break Berkshire Hathaway into smaller pieces. Perhaps Cook should consider a similarly radical decision to break Apple up so that the remaining pieces are small enough to again love niche opportunities that aren’t quite so difficult to pull off. Otherwise, Apple’s next decade runs a high risk of looking like Microsoft’s last — steady performance, attractive cash flows, but an overall sense of stagnation.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

Google’s Strategy vs. Glass’s Potential

Why Germany Dominates the U.S. in Innovation

How Separate Should a Corporate Spin-Off Be?

When an Inability to Make Decisions Is Actually Fear of Conflict

When a company’s planning and decision-making process involves a lot of meetings, discussions, committees, PowerPoint decks, emails, and announcements, but very few hard-and-fast agreements, I call that “decision spin”. Decisions bounce around the company, from group to group, up and down the hierarchy and across the matrix, their details and consequences changing as different stakeholders weigh in. Often, the underlying problem isn’t an inability to make decisions – it’s a tendency to avoid conflict.

Decision spin doesn’t prevent decisions from being made altogether. But they often don’t stick, because people hesitate to express their disagreements during the discussion. There is a lot of head nodding, smiling, and camaraderie — which is undermined later when participants don’t follow through on the decisions that they didn’t really buy into.

Decision spin can be incredibly frustrating at all levels of the organization. It also has a huge impact on cost, productivity, and customer service. For example, when managers at one company I worked with couldn’t agree on the best way (or the few best ways) to configure their sales management software, they ended up with dozens of variations, which not only increased licensing fees, but also made it much more difficult to coordinate sales across divisional or geographic lines. Similarly, when another company needed to reduce its expenses, the pain was spread like peanut butter across the different cost centers because the senior management team couldn’t reach a decision about where to focus — which meant that areas with growth potential lost as much muscle as those with less opportunity.

From the outside, of course, this kind of behavior looks silly. Why can’t managers — even at a very senior level — have open, honest and candid debates, work through their differences, and then reach agreement? That’s what they’re paid to do. Unfortunately, it’s not that easy, for two reasons:

One is that managers are people and have a very human desire to be liked. They want others to think well of them and not feel that they’re difficult to work with. They want to get along and seem like team players. So even when they disagree with something, they often hold back on expressing it too vociferously so as not to get into a fight. In fact, many managers I’ve talked to are afraid that disagreements might turn into uncomfortable battles that will damage or destabilize relationships. So they unconsciously pull their punches to keep things calm.

The second reason for avoiding conflict is that many managers lack the skills to engage in it constructively. Perhaps because of the psychological issues described above, these managers don’t get a lot of practice at conflict, or they’ve never been trained in conflict management. As a result, they miss some of the basic principles and tools necessary to engage in positive conflict, such as defining the overarching goal to be achieved, identifying common ground, focusing on the problem instead of the person, objectively listing points of agreement and disagreement, listening more than talking, and shifting from debating to problem-solving. While none of these principles are rocket science, they’re also not necessarily skills that everyone is born with. And in the absence of these skills, it’s easy for business conflicts and disagreements to quickly escalate into interpersonal tensions — which triggers the avoidance syndrome described above, and a continuation of decision spin.

Breaking this kind of cycle is not easy, particularly if it’s deeply engrained in the culture of your company, and in the emotional makeup of key senior leaders. However, if you want to address it — from wherever you are in the organization — here are two steps that you can take:

First, convene your team, or a group of colleagues, and talk about whether decision spin is an issue. If it is, discuss some real examples, how they played out, and the consequences for the company. Consider whether these are isolated instances or part of a recurring pattern, and what the payoff might be to reduce some of the spin. The key here is to avoid abstractions and build some awareness and alignment about the need to make improvements.

Once you’re in agreement that decision spin is worth attacking, work with your team or your colleagues to develop some ground rules for constructive conflict. These might include giving everyone two minutes to share his or her views; appointing someone to write down pros and cons of an issue; reminding everyone that disagreements are not personal attacks; setting a time limit for debates; or agreeing that decisions don’t get changed unilaterally. Obviously, this is not the same as full-blown conflict management training, but it’s a way to get started — and if you experience some success, it could create the readiness for additional developmental work.

Companies can’t afford to let decisions spin around with no resolution. Shortening that cycle, however, requires managers to understand that conflict should be embraced, rather than avoided.

Focus On: Conflict

Managing a Negative, Out-of-Touch Boss

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Conflict Strategies for Nice People

Senior Managers Won’t Always Get Along

Finding the Balance Between Coaching and Managing

Ask 100 people if they have good common sense, and more than 95% will tell you they do. Ask them if they are good coaches, and almost as many will say yes. Executives we talk to assume that if they’re good managers, then being a good coach is like your shadow on a sunny day. It just naturally follows.

This would be good news, if it were so, since more and more top executives are expecting managers to coach their subordinates. In fact one at Wells Fargo announced that he expects the bank’s managers to dedicate fully two-thirds of their time to coaching subordinates.

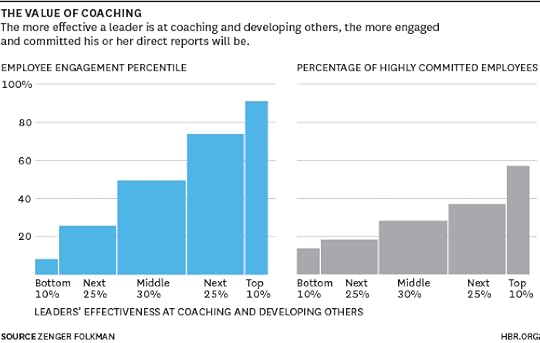

What’s more, employee surveys we’ve conducted over the past decade show that subordinates want coaching. Our own empirical evidence echoes myriad studies in finding that effective coaching raises employee commitment and engagement, productivity, retention rates, customer loyalty, and subordinates’ perception of the strength of upper-level leadership. Responses we’ve collected over the 10 years from some half-million individual contributors worldwide, evaluating about 50,000 of their managers in 360 reviews, show just about a perfect correlation between the leaders’ effectiveness in developing others and the level of their subordinates’ engagement and discretionary effort:

Unfortunately, our long experience helping executives find and develop their strengths has taught us that coaching is not something that comes naturally to everyone. Nor is it a skill that is automatically acquired in the course of learning to manage. And done poorly, it can cause a lot of harm.

What’s more, before they can be taught coaching skills, leaders need to possess some fundamental attributes, many of which are not common managerial strengths. Indeed, some run counter to the behaviors and attributes that get people promoted to managerial positions in the first place. Here are a few of the attributes we have recently begun to measure in an effort to determine what might predict who would make the most effective coaches. You’ll quickly see the conflict between traditional management practices and good coaching traits:

Being directive versus being collaborative. Good managers give direction to the groups they manage, of course, and the willingness to exert leadership is often why they get promoted. But the most effective managers who are also effective coaches learn to be selective about giving direction. Rather than use their conversations as an opportunity to exert a strong influence, make recommendations, and provide unambiguous direction, they take a step back, and try to draw out the views of their talented, experienced staff.

A desire to give advice or to aid in discovery. Subordinates frequently ask managers questions about how they should handle various issues or resolve specific problems. And managers are often promoted to their positions because they are exceptionally good at solving problems. So no one should be surprised to find that many are quick to give advice, rather than taking time to help colleagues or subordinates discover the best solution from within themselves. The best coaches do a little of both.

An inclination to act as the expert or as an equal. We’ve all seen instances when the person with the most technical expertise has been promoted to a supervisory or managerial position. Organizations want leaders to understand their technology. So, naturally, when coaching others, some managers behave as if they possess far greater wisdom than the person being coached. But in assuming the role of guru, the well-meaning manager may treat the person being coached as a novice, or even a child. Still, the excellent coach does not behave as a complete equal, with no special role, valued perspective, or responsibility in the conversation.

How effective is your approach to coaching? We invite you take a coaching evaluation to see where you stand in comparison to outstanding business coaches. It will measure the how strongly you prefer to behave collaboratively or dictatorially, how prone you are to giving advice or enabling other people to discover answers for themselves, and how apt you are to exert your expertise or treat everyone as equals. While certainly the best coaches adjust their style to the particular person and situation at hand, we have found that there are ideal ranges on the scores for all six of these dimensions.

Neuroscience is consistently reminding us that the brain is remarkably plastic. So even though we’ve found a strong correlation between certain traits you may not already possess and the ability to be an effective coach, we have found that people can learn to acquire them — if they are willing to work at it. What that takes is a willingness to step outside your comfort zone and behave in ways that may not be familiar. It’s just like learning to play golf or tennis. What feels awkward at first begins to be more comfortable in time.

Leaders can learn to be more collaborative as opposed to always being directive. They can learn the skill of helping people to discover solutions rather than always first offering advice. They can learn how satisfying it is to treat others with consummate respect and to recognize that in today’s workforce, it is not unusual to have subordinates who are more comfortable with the latest technology than their leaders are.

5 Hidden Assumptions of Tech Privilege

Privilege has been in the news over the past few weeks. At Princeton, an undergraduate’s objections to being told by classmates to “check your privilege” were published as an op-ed in the school’s conservative paper, then reprinted in Time, and then discussed widely in major media outlets like The New York Times.

There are also stories coming from another sort of campus — the manicured lawns and bikeways of tech firms’ headquarters. Last week, Google released its HR statistics showing that, for technology-specific jobs, 94% of its workers are white or Asian, and just 17% are female. The company’s admitted lack of diversity underscores broader challenges in the sector, such as exclusion of women from male-dominated VC networks and homogeneity of thought among the young, white, hoodie-wearing crowd.

On a related note, Pew’s new survey report on the Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable computing, reveals growing concern about the technology sector’s cognitive privilege — a set of unrestrained assumptions, often based in power and influence, about how the world should operate.

Many of the Pew survey’s expert respondents argue that there’s considerable risk to societal well-being if these privilege-based assumptions from the tech sector were to guide the design and development of the Internet of Things over the next decade. If we’re going to ensure an appropriate balance between commercial and societal interests around the Internet of Things, the data suggest technologists will need to put at least five of these assumptions in check now, before it’s too late:

Ubiquitous consent. The assumption now is the Internet of Things is opt-out, not opt-in. With sensors everywhere, there will be an explosion of new opportunities to conduct Big Data experiments on how people behave and interact with other people and things. Those in the privileged “screen everything crowd,” as one respondent in the survey calls them, naturally assume that previous consent to being tracked suggests future consent, with enhanced tracking capabilities.

Another respondent notes, “We will assume these people, brought to us by lenses and digital connections, are there for us. … This urge to watch is so compelling that we will adopt its logic — as we do with all our tools — and we will easily move from watching what we can see, to watching what we could see.”

Needless to say, such an approach is rife with privacy implications and untested areas of law. Assuming my data is available for others to profit creates a kind of digital imperialism.

Your behavior needs to be modified. There’s a privileged notion that the next generation of technology should become an unavoidable path to self-improvement — and that efficiency and errorlessness are always inherently good. As one respondent notes, “The Internet of Things will help more things go right and help more dumb things do smarter things. Anywhere there’s currently a human in the loop, there’s an opportunity for failure, as well as an opportunity for a device to make sure things go right.”

The problem with this is that those that don’t want to adhere to this world view may face new forms of economic discrimination. “Every part of our life will be quantifiable, and eternal, and we will answer to the community for our decisions. For example, skipping the gym will have your gym shoes auto tweet (equivalent) to the peer-to-peer health insurance network that will decide to degrade your premiums,” as another respondent cautions.

Those not buying into the system would need to create new forms of retreat from an everyday life characterized by these activities. Respondents note the emergent need for “Google Glass-free zones,” “personal anti video firewalls around our bodies,” and “technology shabbats” — a day of the week where we figure out a place that’s off the grid.

Perceptual insufficiency. Another assumption is that our natural experience of the world is (or soon will be) insufficient. The report mentions dozens of examples of new tools that will help us survive and thrive in the Internet of Things, where data-mediation and analytic decision-making become oxygen for everyday living. Augmented reality (AR) glasses will superimpose information to improve vision and decisions about health and nutrition as we buy groceries, for example; virtual reality (VR) headsets will create immersive connections to loved ones in other environments.

Respondents voiced many concerns about potential consequences of this assumption getting baked into the development of the IoT. Walking down the street will become risker as data is literally cast into your field of vision; life will feel more filtered and moral responsibilities more abstracted; meaning could decay in relationships that have long been based on direct physical interaction, such as in parenting and marriage. And when you do see others directly, you may feel a sense of “social exhaustion” as a result of perpetual feedback and “stimulation due to always-available computing.”

New gadgets are a precondition to human flourishing. As the circuitry of the Internet gets woven into the basics of life — into clothing, home heating systems, fields of corn, and car engines — there’s greater potential to use personal analytics tools to improve health and well-being. Want to gather detailed physiological data to share at your next doctor visit? Wear a health monitoring shirt. Want to figure out how to lower your utility bill? Install a Nest Thermostat, which will analyze your energy habits and use algorithms to reduce energy consumption.

Yet, many respondents voiced concern that this logic could also lead to an even wider digital divide. What about those unable to buy the beneficial tools that interact with ubiquitous sensors? As one respondent opines, “just as students today are burdened if they don’t have home Internet … there will be an expectation that successful living as a human will require being equipped with pricey accoutrements. … Reflecting on this makes me concerned that as the digital divide widens, people left behind will be increasingly invisible and increasingly seen as less than full humans.”

Humans are things, too. A fifth assumption is rooted in the construction and interpretation of rhetoric. To some the phrase ‘The Internet of Things” implies that people, linked to ubiquitous cloud networks with tools like wearable technology, are “just another category of things.”

Rather than technology being at the service of people, the reverse takes hold: people become “nodes” constantly transmitting and receiving data. “Google Glass is already part of Google’s sensory network, with all images and sounds that the user obtains sent onto Google’s servers for storage and analysis,” observes one respondent.

Too often, these five assumptions reveal possibilities for technological invention decoupled from consumer needs: technology for technology’s sake. While the Internet of Things suggests something vast, creating economic and social value will require a lot of small scale experiments. These will give users a say in whether an application is truly solving a problem — or creating a new one based on a faulty assumption or an unconscious exercise of privilege.

To Negotiate Effectively, First Shake Hands

Negotiations − especially when they involve high stakes, complex issues, and multiple parties — require much thinking and preparation on each side of the bargaining table. Consider the recent negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. Even before the contentious talks actually started, U.S. President Barack Obama and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani scheduled a meeting that took months to arrange. There was only one item on the agenda for the meeting: a handshake. At the last moment, however, Rouhani decided not to meet Obama, leading American pundits to call the incident the “historic non-handshake” that risked compromising the quality of the ensuing negotiations.

People make inferences about one another’s motives based on first impressions, which occur extremely quickly. We only need 100 milliseconds to form judgments of others on all sorts of dimensions, including likeability, trustworthiness, competence, and aggressiveness. Even more interesting, our first impressions of others are generally accurate and reliable. For instance, first impressions about a person’s competence have been shown to be good predictors of important outcomes such as who will win a political election.

Handshakes can create a positive first impression by conveying a sociable personality. In one study, a firm handshake was positively related to extraversion and emotional expressiveness and negatively related to shyness and neuroticism. Another study found that people who follow common prescriptions for shaking hands, such as using a firm grip and looking the other person in the eye, also receive higher ratings of employment suitability in job interviews. Witnessing people shaking hands in a business setting not only leads third-party observers to more positively evaluate the relationship, but it even increases activation in the nucleus accumbens in the observers’ brains — the area associated with reward sensitivity. That is, we feel rewarded simply by watching others shake hands!

In the context of a negotiation, a handshake’s message can go even further, my research finds. Consider that we all rely on subtle sources of information to determine whether to behave in cooperative or antagonistic ways during our negotiations. One such source of information is nonverbal behavior, including handshakes. Across many cultures, shaking hands at the beginning and end of a negotiating session conveys a willingness to cooperate and reach a deal that considers the interests of the parties at the table. By paying attention to this behavior, negotiators can communicate their motives and intentions, and better understand how the other side is approaching discussions.

In one study, colleagues at Harvard’s and the University of Chicago’s business schools and I asked pairs of executives to negotiate as the buyer and seller in a hypothetical real estate deal. The executives had to negotiate over one issue only: the price of the land. In the simulation, the seller believed that the property under consideration was zoned for residential use only, but the buyer knew that the zoning laws would change soon, allowing the buyer to develop the land for commercial use and thereby making it much more valuable. Clearly, the buyer had little interest in sharing this information with the seller. In fact, when asked by sellers whether they intended to use the land for commercial development, many buyers lied or dodged the question altogether.

We instructed half of the pairs to shake hands before negotiating. We did not give specific instructions to the other half about handshaking, our control condition. Most of them just jumped into the negotiation without shaking hands first, presumably because they were under time pressure. Pairs who had been asked to shake hands divided up the pie more evenly than did those in the control condition. In addition, buyers in the pairs who had been asked to shake hands were less misleading about the zoning change than were buyers in the control condition.

In follow-up studies, we tested whether these results held for integrative negotiations — those where parties could discuss multiple issues and potentially create value. In one experiment, for instance, we randomly assigned undergraduate students to the role of “hiring boss” or “job candidate” and gave them time to prepare individually for the negotiation to determine the latter’s salary, start date, and office location. The students in the role of job candidates knew they had the job if they wanted it, but they needed to negotiate the details with the hiring boss. Both parties were instructed to prefer the same location and have opposing starting positions on salary and start date. Because the candidate cared more about salary and the boss cared more about start date, the solution that maximized the joint outcomes was to allow the candidate the highest salary and the boss the earliest start date. We told the pairs that the participant who received the better score in the negotiation would earn a financial bonus (for real!).

Half of the pairs were accompanied to the table where they would negotiate and told, “It is customary for people to shake hands prior to starting a negotiation.” The other half of the pairs was seated immediately and thus had no opportunity to shake hands. Pairs then negotiated for no more than 10 minutes. Two research assistants who were blind to the hypotheses of the study coded videotapes of the negotiations on a variety of criteria, including our main measure of interest: the parties’ openness in discussing their individual priorities throughout the negotiation. The result: Shaking hands induced greater openness about negotiators’ preferences on contentious issues and improved joint outcomes.

When I was little, I often got into conflicts with my brother and sister over toys or books. As in many other families across the globe, my parents used to tell us to “shake hands and make up.” Their words conveyed the belief that the simple gesture would induce cooperation and goodwill. As my research and others’ shows, the simple act of shaking hands is indeed a powerful gesture in negotiation.

Focus On: Negotiating

Make Your Emotions Work for You in Negotiations

The One-Minute Trick to Negotiating Like a Boss

How to Negotiate Your Next Salary

Should You Eat While You Negotiate?

A Benefit of the Mechanization of War: Savings on Veterans’ Benefits

The most overt costs of war, including military spending and the destruction of capital, are of relatively short duration, but the costs borne by combatants, caretakers, and society last for many years. Thus, committing troops to a war zone has lasting implications for fiscal policy: Depending on the scope of the conflict, the government’s obligation to pay veterans’ benefits can run as high as 50% of the nation’s prewar GDP, according to a study of U.S. wars by Ryan D. Edwards of the City University of New York. Even an expensive mechanized war, with the loss of large amounts of costly equipment, may be not only far preferable in terms of reduced loss of life and limb but may be far cheaper in the long run if it conserves future veterans’ benefits, Edwards suggests in the Journal of Public Economics.

The Rebirth of U.S. Manufacturing: Myth or Reality?

The media has been full of reports lately about a renaissance in U.S. manufacturing. The cheerleaders cite an array of heartening examples, including a $4 billion investment by Dow Chemical to boost its ethylene and propylene capacity on the U.S. Gulf Coast, an announcement by Flextronics of plans to create a $32 million product innovation center in Silicon Valley, and a decision by Airbus to build a $600 million assembly line in Alabama for its jetliners. These stories have prompted much talk about the “reshoring” of manufacturing jobs to the U.S. from China and elsewhere. Indeed, President Obama recently hailed “a manufacturing sector that’s adding jobs for the first time since the 1990s.”

But is this revival for real? Forbes has derided the notion of a U.S. manufacturing comeback as “a cruel political hoax.” And the New York Times recently ran an editorial by Steven Rattner entitled “The Myth of Industrial Rebound.”

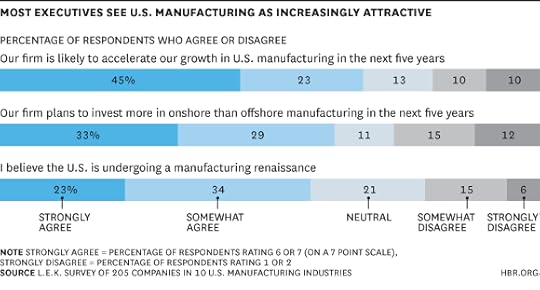

A lack of detailed data has made it hard to assess what’s really going on within the U.S. manufacturing sector. To help remedy this, L.E.K. Consulting conducted a study of decision makers in 10 U.S. manufacturing industries, including aerospace and defense equipment, chemicals, industrial components, automotive equipment, and electronics. The study, which focused on large companies with more than $500 million in revenues, also involved in-depth interviews with high-level executives about the factors driving their decisions on where to locate their manufacturing.

The picture that emerges from this research is less black and white than either the cheerleaders or the naysayers would suggest. Overall, we see a modest improvement in U.S. manufacturing but not a wave of reshoring. More companies are investing in the U.S. or considering it as a location for new manufacturing facilities. But this is essentially a rebalancing after many years in which manufacturing shifted overwhelmingly to lower-cost nations such as China.

Intriguingly, the study also indicates that cost factors are no longer the key consideration for many companies deciding where to locate their manufacturing. The leading factors driving companies to manufacture in the U.S. include a growing desire to locate their manufacturing near their customers so they can respond quickly and efficiently to customer needs and drive growth, while simultaneously de-risking the supply-chain. A corporate strategist for one manufacturer told us: “It’s tough to get the same quality level and cycle time to serve your customers if your supplier networks are far away.” At the same time, these companies are continuing to invest in manufacturing outside the U.S., particularly in emerging markets, for many of the same reasons. So the picture is truly nuanced.

The CEO of a manufacturer in the automotive industry added: “We hesitate to put a component or product that requires high, stringent control in many developing countries.” In fact, American companies often have a competitive advantage when it comes to producing technologically advanced, differentiated goods that require precision manufacturing and a high level of quality control. As a corporate strategist at one U.S. manufacturer put it: “Overall, the harder the skill required, the closer to home we keep it.”

Costs are just one component of a more complex equation, but they clearly remain a significant factor. Thanks to the boom in U.S. oil and gas, the country now possesses an abundance of inexpensive energy. As a result, the U.S. is an increasingly attractive location for manufacturers that are energy intensive or that can use natural gas as a primary input. Clear winners are chemicals and petrochemicals (e.g., plastics), and also sectors that serve those industries. An executive at an energy equipment manufacturer told us: “For industries like chemical processing or metals manufacturing, energy costs are a much bigger deal than for machined and electronic goods and could certainly cause companies to relocate.” By contrast, energy costs are less important in industries like furniture and textiles; so manufacturers in these areas are less likely to reshore to the U.S.

In the past, a key driver for companies to move their manufacturing out of the U.S. was to save money on labor. The difference in labor costs is still significant, but it has narrowed as wages have risen elsewhere. The strengthening of China’s currency has further eroded this cost advantage, and U.S. manufacturers have also closed the gap somewhat by enhancing their productivity and their use of automation. According to the global business director at a welding-equipment manufacturer, fierce overseas competition “has forced the evolution of the industrial base in the U.S., where many industrial manufacturers have become lean [and] automated to survive.” So our study suggests that labor costs are no longer the dominant factor in determining where companies base their manufacturing.

In the future, many commoditized products will continue to be made offshore. In the U.S., we expect a growing emphasis on more sophisticated manufacturing, including the use of 3-D printing to accelerate product development. This cutting-edge technology holds particular promise for the type of complex, low-volume products developed in industries such as aerospace and defense.

What could deter manufacturers from investing in U.S.-based manufacturing? Our survey respondents suggest that high corporate taxes and regulatory uncertainty are the two biggest factors hindering U.S. manufacturing from growing faster. Manufacturers in lower-cost countries such as China are also raising their game, not least by improving their own use of automation.

In general, we don’t expect many companies to close their existing facilities in China and to reshore them in the U.S. But we do expect many companies to locate new manufacturing facilities in the U.S., particularly in sectors such as aerospace and defense, industrial manufacturing, oil and gas, and the automotive industry. The bottom line is that companies will locate close to where their growth is originating. This doesn’t amount to a renaissance or a new dawn. But after decades of decline, it’s a welcome advance.

June 3, 2014

Disrupting the Gaming Industry with the Same Old Playbook

With a market size of $8 billion in 2013 Massive Multiplayer Online Gaming (MMOG) is becoming big business. It’s not just about the players, either: people are going online just to watch the games being played, a global viewership estimated at about 71.5 million as of 2013.

Welcome to the brave new world of e-Sports. Some MMOG professional teams players can command six figure salaries, thanks to the finance provided by corporate sponsorships and advertising. Recently the USA recognized professional e-gamers as pro athletes eligible for P-1A visas.

The MMOG that epitomizes the birth of this new industry is perhaps League of Legends (LoL). LoL’s core gaming business is built around by the Free to Play model in which community building and social engagement are the main objectives. The model is in part monetized through micro-transactions in which virtual goods used in the game are purchased with real currency. The game has been popular since its release in the 2009 and has an active unique monthly user base of 67 million, generating $625 million in annual revenue.

But the real revenue driver is viewership. Online broadcasting channels are filling up the distribution space just as television did in conventional sports. Twitch.tv — one of the leading on-line game streaming channels — has partnered with game publishers and game console makers to add features that allow gamers to stream their game play live or recorded over the channel. Revenue flows primarily from the online ads targeting the soaring viewership.

And what a viewership! LoL’s 2013 World Championship garnered online viewership of 32 million on Twitch.tv alone, significantly more than Game 7 of the 2013 NBA Finals, which had a peak viewership of about 26 million over various media formats. The event itself in the Los Angeles Staples Centre was a sell-out. Sponsors included big names like Coca Cola, Intel, and Amex, all looking to reconnect to the lucrative demographics (18-35) LoL caters to.

This all sounds splendidly disruptive: new technology-enabled social media redefining what we think of as sport. Yet the hype tends to obscure just how familiar the story actually is and just how much of the success is the result of canny business folk applying a well-used playbook.

What LoL is doing in MMOGs is pretty much repeating what shoe manufacturer Vans did for skateboarding. A fad for 20 years up to the 1990s, skateboarding was haphazard and disorganized: it lacked adult supervision, provided few external rewards and was widely seen as solitary activity for misfits. No sponsors or advertisers invested in it. At certain moments, only the enthusiasm of skateboarders kept the sport alive.

Until Vans made its move. The company institutionalized the sport creating a world championship as a way to recognize player excellence and found a mass audience by selling rights to ESPN and similar channels. It invested in organized and parent-friendly skateboard parks; produced a Sundance festival winner documentary on the history of skateboard (Dogtown and Z-boys); and sponsored the Warped Tour, a series of concerts in various cities showcasing trendy, cool music in line with the skateboarding lifestyle.

In other words, just as LoL is doing today, Vans created a sports ecosystem. Its festivals, skateboard parks, and world championships represented new business lines, most of them profitable in the first half of 2000s. But the real benefit for Vans was that its strategy made the sport mainstream and opened it up to the masses, which ultimately had huge benefits for its core shoes and clothing businesses.

Stories like LoL and Vans illustrate a profound truth about strategy and business. Industries are reinvented and new ones are born all the time. But this does not mean that the strategies by which they are redefined or created also change. If anything, the stories of LoL and Vans illustrates just how enduring strategy actually is. Disruption doesn’t change the rules for good strategic moves — rather, it gives new players more opportunities to apply them.

Share Your Financials to Engage Employees

If you’re searching for ways to improve employee engagement, you’ll find lots of laundry lists. Fourteen tips. Seven steps. The “Ten C’s.” Most of these sources contain good-but-basic advice, like providing mentoring, encouraging two-way communication, and recognizing people when they do great work.

But the statistics suggest that following such advice, like staying on a diet, is harder than it looks—some 70% of U.S. workers say they don’t feel engaged on the job, a number that hasn’t changed much in recent years. If time-starved owners or managers don’t naturally abide by all those nostrums, are they likely to start now?

We have a different way of thinking about engagement, because we have a different idea of what it is.

Our approach begins with a question: Who do you think is more engaged in the business, the farmer or the hired hand? The building contractor or the guy pounding nails? The store owner or the clerk behind the counter? The answers are obvious, but they raise an equally obvious objection. Not everyone can be an owner. And as a National Bureau of Economic Research study shows, even employees who hold an ownership stake in their employer aren’t necessarily more engaged or motivated than their nonshareholding peers.

But the objection misses the essence of ownership. It isn’t just that owners are in charge. It’s that they’re players. They’re in the game. They know the rules. They act, and they watch the numbers to find out whether their actions were on track or misguided. If they win the game, they know there’ll be a payoff. Most people think of engagement in individual terms—feeling fulfilled by the task at hand, wanting to do a good job. We see engagement as being part of a team that’s competing to win.

It’s surprisingly easy to generate this kind of engagement among employees when you make the economics of the business come alive by sharing some key financial numbers. It’s an open-book approach: people begin to watch these indicators. Then they figure out how to move them in the right direction.

A while ago, for instance, a global travel-management company picked three representative U.S. branches to pilot open-book methods of building engagement and improving performance. The company’s team identified a critical financial number—site revenue minus direct site costs, known as direct profitability. Branch employees then began meeting every week to review these financial results, brainstorm ideas for improvement, and forecast future results.

In the past, the company’s front-line travel counselors had behaved pretty much like employees everywhere. They did a competent job, but they didn’t worry about the financial implications of a changed itinerary or a new hotel pricing policy. Now—engaged in the business of improving their branch’s numbers—they began spotting opportunities an owner might think of. A customer-relations rep in St. Louis, for instance, contacted vendors to recover money lost due to hotel no-shows and canceled flights. Over the first few months she collected $189,093—a significant savings for the company.

Each pilot branch generated several such ideas, which they then shared with the other two. At the end of the pilot period, the experimental branches had exceeded their profit budgets by 10%, 17%, and 20%, resulting in more than $1.7 million in incremental earnings. None of the other U.S. branches hit budget that year.

We’ve witnessed similar results at many other companies that follow the open-book path to engagement. A designer at a D.C.–area design/build firm says she notices “everyone caring more and being more accountable and taking responsibility.” The CEO of a midsized manufacturing company told us, “I don’t have employees in my plant anymore. I have entrepreneurs who are looking to find ways to make more money.” At one company, employees even organized small betting pools around the accuracy of each month’s profit forecast. (Now that’s engagement.)

Most open-book companies tie incentive compensation to improvement in the key financial numbers, so employees see a payoff as well. But the real engagement comes from thinking and acting like owners.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers