Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1411

June 11, 2014

Navigating an Office Without Formal Processes

You just changed jobs from a highly structured, corporate company to a much more casual environment. You may be finding that adjustment difficult. Maybe you’re wondering: Where is the meeting software, and do I really have to use this nap room? The Silicon Valley office with its pool tables, free-flowing beer, and hoodie-clad CEO is a cultural cliché, but many offices are becoming more casual – not only more relaxed socially, but also in their policies and processes. Zappos is getting rid of traditional management structures and even job titles. Netflix has done away with vacation and expense reporting policies. Adobe axed formal performance appraisals. If you’re entering such a company from a more rules-driven company, do you have to change – and how much?

What the Experts Say

Adaptation is the name of the game, says Amy Jen Su, a managing partner and co-founder of Isis Associates and coauthor of Own the Room. “Part of performance success is understanding the culture you work in and being able to appropriately adapt to it,” she explains. “Working with the culture will affect whether you succeed at your job so it’s important to get it right.”

At the same time, your new office values your skills—that’s why they hired you. The trick is to adapt without losing your confidence or what has made you a successful in the past, says Dr. Karie Willyerd, a senior vice president at Success Factors. You have to learn what works best in the new environment.

Here are four principles to follow when navigating a new, less structured company culture.

Observe three key aspects of corporate culture

Since corporate norms might not be obvious at a more casual workplace, when you’re starting a new job, step one is to go into high observation mode. Start by simply looking at when people are working. “Look at work time-frames—when people come and go, what times certain colleagues are in or not in,” says Jen Su. Then take note of how communication flows—is it virtual or face-to-face? Who are the pockets of people in these conversations? Finally, observe tactics of persuasion: how people get buy-in and how key decisions are made.

Identify effective coworkers

If you can’t figure out the flow of the office and you’re not getting the right players to collaborate on projects you need to accomplish, Jen Su suggests taking a particularly effective or long-tenured coworker out to lunch. Say something like, “I love how you got the whole team to buy into X. I’d love to hear about how that works here. Any suggestions or tips for me?”

Don’t underestimate the importance of office socializing

In an office with minimal formal policies and procedures, informal influence can take on outsized importance. “Relationships matter because they help bridge the lack of process,” Willyerd says. Skipping happy hours or holding back about your personal life not only make you seem out of step; they also reduce your persuasive power.

If you’re an older worker or a parent, going out for drinks may not be realistic – or appealing. But there are workarounds. Willyerd suggests lunch events, because it’s the socializing that matters, not the after-hours margaritas. “Figure out alternative ways to get to know people personally and build relationships,” she says.

If the idea of emoting with colleagues makes you want to run for the door, stick to safer personal topics. “Kids and family are an easy one,” says Jen Su. She described a former client who would talk to other parents at the office about trying to find a pre-school for her three-year-old. If that still seems too personal, just having conversation about how you spent your weekend can be a way to connect without over-sharing, and allow you to be authentic without feeling vulnerable, says Jen Su.

“In a casual business environment, relationships matter and help to bridge the lack of process,” Willyerd says. “Trust and authenticity are key when decisions are made quickly without the time to socialize everyone involved.”

Introduce structure when it adds value

Adapting to a more casual office doesn’t mean giving in to inefficiency, however. You can introduce more formalized process improvements if they really help. Perhaps at your old office, meetings were always scheduled with Outlook. At the new office, a preference for informal discussions is causing endless email strings or constant interruptions, and you’d like to suggest implementing some kind of meeting software. Willyerd says the way to go about it is to show how your idea will benefit your new organization. . “In a casual environment, you would not introduce a new process or tool simply for consistency’s sake, to make you more comfortable,” she explains. “So explain the value the new tool or process brings to everyone. With a good story this week, you could be on Outlook next week.”

Jen Su points to risk management as an area where your new organization might welcome more formal processes. “If you notice that the casualness means there could be a risk to governance, or ethics — for example, the online security systems aren’t as good as the ones at your old workplace — it’s a great opportunity to suggest changes,” she says.

Be extremely mindful of the language you use, however. A constant refrain of “when I was at Company X, we used to…” will undoubtedly prompt eye-rolling among your new colleagues, Willyerd says.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Spend your first weeks in deep observation mode

Take an effective coworker out to lunch and ask her for advice

Be authentic without oversharing

Don’t:

Use your old company as a benchmark of how things ought to get done

Bring in practices from your previous employer just to make yourself more comfortable – only introduce them if they’re in the best interest of your new company

Lose your confidence – they hired you for a reason

Case Study #1: Be selective with the changes you’re advocating

Margo Schlossberg is a marketing manager for a chain of auto repair shops – an environment she prefers to the Fortune 500 company where she previously worked.

Because her new firm’s project management processes felt disorganized, relative to ones she’d previously used, she tried to introduce her new marketing colleagues to a system called Basecamp. She sent out invitations to join, but they were ignored, so she backed off.

“It’s a work in process, and it may happen some day in the future as the organization looks to expand,” she explains.

She did succeed in getting her boss to use Google Docs, “which was a win”, and hopes to convert more people to that sharing tool. She’s also keeping her eye out for situations in which she can explain the benefits of more formal project management tools. “I can only try to point out in a logical manner the opportunity cost of not using systems to be more organized,” she says.

Case Study #2: Use a new process to build trust

When Austin Melton went from an old-school media company where he wore a suit and tie to a creative agency run by young executives called liquidfish, where jeans and sneakers were the norm, it was a bit of a shock, says the Oklahoma City-based digital marketing manager. “There’s a full bar and a keg at my office now. If I were in my previous job having drinks at work, I would be called into HR.”.

But the biggest adjustment was getting used to how his new employer prepares profit and loss statements. “I was used to working closely with P&Ls at my previous job so I could stay on top of the department’s revenue and profitability goals,” Melton explains. At his new company, his boss simply keyed figures for the whole company into accounting software without breaking P&L down by department or forecasting for the next quarter.

Melton felt he had to create his own P&L to track his team’s revenue allocations, expenses and profitability, and set forecasts in order to make effective decisions. At first, “the owner was a bit taken back,” he says. But ultimately his boss has been pleased with how smoothly his department was running. Department-specific P&L forecasting has not yet been implemented for other directors, but it’s been an essential tool for Melton because of the work his particular department does.

By taking the initiative to institute more formal processes, “I was able to keep my part of the company running smoothly and build trust with my boss,” Melton says.

A Small Firm’s Response to Higher Health Care Costs

There are many reasons I love May – the flowers and leaves emerge, including those on the tree right outside my office window in downtown Boston; it’s light enough to play golf until 8PM; and we banish our heavy wools to make room for light-weight clothes. However, here’s what I hate about May – my company’s health insurance plan comes up for renewal.

I cower when I see the email from our health insurance broker, cheerfully writing to schedule our annual plan review and a discussion of the increase for the coming year. I say increase because we have never seen a decrease in the 10 years of such meetings. Having heard in the media recently that health insurance plans were seeing dramatic price jumps, I didn’t even ask our agent, Bob, what the increase was in advance, because I didn’t want to extend my inevitable agony.

Since our financial services firm’s inception in 2005, we have had a PPO (Preferred Provider Organization) plan fully funded by the partnership. Some of us had prior nightmarish experiences with HMOs and we wanted to avoid the gatekeeper process for referrals. Despite switching a couple of times among the few insurers in Massachusetts, we have stayed at the high end of the spectrum; this past year, across our 29 covered lives, that plan cost us $1546 a month per family and $581 per individual.

When Bob came to the office to meet with three of us who serve as the unofficial “health insurance committee,” the first words out of his mouth were, “This isn’t good.” He then proceeded to tell us the news: a 34.9% price increase! Bob can be a master of understatement. I was expecting bad, but this was insane. All I could say was, “You’re kidding, right?”

He wasn’t. He explained that for decades, the financial services industry has enjoyed a relatively low cost of insurance compared with other Massachusetts industries (could have fooled me), since their members and families use far less medical care than some other industries, such as construction and manufacturing, whose premiums were historically greater, reflecting their higher per-capita use. Unbelievably, it turns out that our $18,552 per family per year was really a bargain compared to a moving company! And also under the Affordable Care Act, insurers can no longer discriminate by sector, and companies with less than 50 employees, such as ours, cannot band together to negotiate lower rates.

We asked Bob what we could do. He mentioned a very similar plan offered by another carrier that would “only” cost 11% more than our current plan. (What’s the inflation rate again?)

While this option seemed the clear winner if we wanted to continue to fully underwrite the best package, I wondered if perhaps it was time to rethink our strategy of fully funding employees’ PPO plans. Do employees really value this benefit, and if not, should we consider alternative approaches? Maybe we should start only covering a portion of the plan (as many other employers do) or offering a stipend that could be applied to a few different insurance plans.

To explore where employees rate their health insurance benefits among other job benefits, I surveyed over 50 people and asked them to simply list the top five aspects of their job in order of preference, without offering any choices so I would not “lead the witness.” Because I assumed higher-level executives would be less likely to describe health benefits as a top-five attribute, I surveyed a wide ranging group of workers within different organizational structures, but all were white-collar office workers.

Not one person listed health insurance within their top five. Intellectual challenge was the most cited first choice, with colleagues and salary tied for second place. Several people mentioned the length of their commute or their offices.

I then asked if people liked their health insurance and what percent their employer paid. Everyone said they were pleased with their plan, even though several did not know what percent their company paid. Those who did reported that their companies contributed 75-80% of the premium. Despite the relatively small sample size, it seemed clear that a fully funded health plan was not top-of-mind for people considering their favorite elements of their jobs.

What, then, were the options I could offer my colleagues? We could keep the existing plan but not cover the price hike. We could keep it and pay a portion of the increase, requiring employees to contribute the remainder. Or we could switch to another, similar plan and either absorb or share the increase. Discussions with my partners on the subject contained a certain friction, as people are always anxious and suspicious about issues that involve change, money, and trust. I also worried about seeming uncaring and motivated by other concerns than the welfare of our staff.

We recalled that two years ago, facing an increase in the 20% range, we moved to a plan just below the most expensive offering. The plan we chose then had a $500 deductible for the first surgical procedure. Since the switch would save us many thousands in premiums, we told our staff that the company would cover the deductible for the first surgery within any family. Since then, we have saved close to $30,000 in premiums, while only spending $2,000 in reimbursing deductibles for four surgeries.

So last month, we decided to pursue a similar approach. We switched to the alternate plan – the one with the 11% increase per capita — and we will provide $500 per person toward the $1,000 cumulative family deductible for surgeries, diagnostic tests, or in-patient stays. Next year, depending on the level of price increase, we my look into offering a few options with some employee responsibility, but this market is changing so fast, it’s hard to even imagine the landscape 12 months from now.

By then, there may be some valuable data from the experience of the Affordable Care Act to help enterprises struggling with these decisions. In the meantime, I will be curious to see if anyone at our company notices that they have an incremental increase of $500 per family deductible.

Keep Learning Once You Hit the C-Suite

What skills do companies prize in C-level executives ? To answer these questions, we surveyed 32 senior search consultants at a top global executive-placement firm. Experienced search consultants typically interview hundreds and even thousands of senior executives; they assess those executives’ skills, track them over time, and in some cases place the same executive in a series of jobs. They also observe how executives negotiate, what matters most to them in hiring contracts, and how they decide whether to change companies. (See my posts on “The Seven Skills You Need to Thrive in the C-Suite” and “Headhunters Reveal What Candidates Want”)

Many consultants emphasized that executives need a first-rate core of technical and soft skills. These skills will vary by industry and function, but up-to-date financial, technical, managerial, and leadership skills are of universal value. The terms “flexible,” “adaptable,” and “curious” came up frequently. One consultant described a typical in-demand executive as “a sponge,” primed to “take in new skills” and “learn from the people around them.” Another endorsed “willingness to learn and adapt to changing environments,” and a third urged “adaptability, the ability to operate in multi-cultural environments and the openness to learn.” One consultant virtually spelled out a formal specification: “Executives should not only have a high level of intellectual curiosity (staying current on market trends and changing dynamics in business), but also a personal sense of flexibility and adaptability.” Several consultants urged executives to build on their personal strengths, or, in the words of one respondent, to “stay very focused and honest on where their core strengths lie.”

Several consultants urged executives to refresh their technical skills constantly. “It is always important to keep oneself up to date with what is happening in the industry,” one said. “Updating one’s IT skills and getting acquainted with the new ways of communicating and interacting (social media) are obviously also very important.” Another urged executives to “continue to educate themselves commercially, financially, and operationally.”

Some argued that merely keeping pace with industry and market changes is inadequate; an executive must anticipate change. The costs of not doing so—not continuously changing and evolving—are likely to be high. Those who neglect to keep up, one respondent said, “will be left behind in a rapidly changing market.”

Finally, team-building skills are both highly prized and shifting rapidly: executives are apt to find themselves managing co-located teams, cross-functional teams, global teams, and virtual teams. Accordingly, they are increasingly expected to apply an analytical lens to team management and to be familiar with best practices (as opposed to managing by gut).

Where should executives turn for advice on skills they need to acquire and upgrade? According to the search consultants, executives might also want to seek out these four sources of insight:

Self–assessment. Many consultants stressed astringent self-reflection, urging honest self-scrutiny about one’s shortcomings and developmental needs before turning to peers, colleagues, mentors, coaches, or courses. “Be extremely critical of yourself,” one counseled. Another urged “listening, adapting, and being cognizant about your own strengths and weaknesses.” The risks of complacency and arrogance arose repeatedly. As antidotes, some recommended flexibility, openness, and willingness to listen. “[Leaders] need to be constantly testing how people are responding to them,” one consultant said, “and open to adjusting their style—both in how they communicate with different groups of people and how they change their leadership approach to suit the situation.”

Peer and subordinate feedback. “External awareness”— which one consultant described as “the ability to seek information outside the executive’s classic sphere”—was viewed as just as important as self-awareness. Several respondents advocated a “strong and diverse network” and openness to 360-degree feedback—that is, not just feedback from supervisors. One even declared that executives “should always be asking their team, peers, and boss how they can be better.”

The same relationships that can fortify executives’ self-knowledge can also keep them abreast of the market and the industry. One consultant urged executives to “seek advice at all levels, and leverage the experts they have in their businesses—this helps build trusted relationships as well as provide them with valuable information.” Another noted one hazard of failing to do so: “Too often I see good executives focused only on their role, and not interested in spending time building a good network of peers. The consequence is that they miss the weak signals of the market.”

Mentoring. Many respondents recommended a mentor—one whose career trajectory the executive hopes to emulate—as a source of information and advice. “Analyze the success of others in their company,” one consultant suggested, “and don’t be afraid to seek out a mentor.” Others extolled the benefits of taking a more junior colleague as a mentor, or “reverse mentoring.” “In a few cases we have been successful in implementing a ‘reverse’ mentoring program, i.e., giving an under-30-year-old mentor to an executive of 54 years of age or older,” one consultant said. “They have been helpful in changing some old habits and ways of thinking.” The junior partners tend to be front-line managers and professionals with up-to-the-minute knowledge of customers, competitors, products, technologies, and trends.

Formal education and developmental assignments. Some consultants praised external educational offerings, including formal executive-education courses, for the access they offer to new research and practices, examples of companies facing relevant challenges, and sometimes a global network of contacts.

Others advocated seeking out varied and off-track job assignments, or what one consultant called “opportunities that take one out of one’s comfort zone.” Developmental assignments outside one’s areas of expertise can often provide exposure to new practices, new markets, and disruptive technologies.

Professional coaches were also cited as a source of reliable but confidential feedback about oneself and one’s managerial skills. “Having a coach or peer group to bounce ideas off is important as execs review their own performance critically,” said one consultant. “An impartial outsider is often required.” Coaches can help executives correct their blind spots and weaknesses, and offer valuable negative feedback that subordinates might withhold.

As one executive offered advice for the long haul: “Do not spread yourself too thinly, and focus on the objectives you have been given. Ensure you have a happy and healthy support system outside of work, and make this a priority.” Some cautioned, too, that flexibility ought not to displace long-term objectives. The goal, one consultant said, is to “stay open-minded but remain on purpose.” Another warned against embracing fads and “every whimsical management book that comes to the market.” Another observed, “The problem is not the sources of information. It is about the analytical and reflective capacity to sort through all that information and pick what is specific to their needs.”

Today, the most pressing question is,“How can you keep your skills current?” It’s really a question of career survival.

About the Research

We talked to the 32 consultants in 2010, but the findings are consistent with everything we hear today. As a group, the senior search consultants we spoke to were 57% male and 43% female. They represented a wide range of industries, including industrial (28%), financial (19%), consumer (13%), technology (11%), corporate (6%), functional practice (6%), education/social enterprise (4%), and life sciences (4%). These senior search consultants worked in 19 different countries from every region of the world, including North American (34%), Europe (28%), Asia/India (26%), Australia/New Zealand (6%), Africa (4%) and South America (2%).

Don’t Hide When Your Boss Is Mad at You

Years ago, as the editor of prestigious trade magazine, I remember losing my cool with one of the top reporters. We were sharing a late-night cab home from the office, both having put in a long day, and when I pressed her on when I’d finally see the very late article she’d been laboring over, she told me she wasn’t sure she’d make the deadline, or any deadline that would allow the article to be printed in the next issue of the magazine. Caught by surprise, I lost it and started yelling at her. All the things I’d have to do to fix the problem were running through my mind. I was angrier than I’d ever been in my professional career and when I got out of the cab, I slammed the door as hard as I could. She avoided me the whole next day at work and the tension between us festered for a few days until I came up with a new piece to fill the hole in the magazine. Only then was I able to rationally discuss her article with her – and when it was finally finished, it was a great piece.

It was not my finest moment as a manager, but I can imagine it was even worse for her. Nobody wants to be on their boss’s bad side. After all, study after study shows how critical the relationship with your manager to your happiness at work. Not to mention that your boss controls many aspects of your working life, from assignments and raises to vacation requests.

In hindsight, I wished I’d handled the matter differently. As the boss, I should’ve discussed the problem with her calmly in the morning, when we were both rested and I’d had time to rationally think through the implications of her missing the deadline. But bosses, like everyone, aren’t perfect, and sometimes it’s up to the employee to make amends. It’s hard to step up, especially given the difference in power, but if you want to recover from making your boss angry, it’s important to not be timid and take the lead. Here’s how.

Don’t retreat to the shadows. Don’t be tempted to hide from your boss or sweep the conflict under the rug. That can cause the tension to fester and lead to future blow-ups, perhaps disproportional to the original offense. It’s critical that you attend to the working relationship if it’s been damaged, says Jeff Weiss, partner in Vantage Partners, a consultancy that specializes in negotiations and relationship management. Don’t wait for your boss to take the initiative to smooth things over. When you’re feeling calm and rational, go see your boss to clear the air.

Get input. Resist the urge to gossip about what happened with your colleagues. You can inflame a tense situation quickly if everyone is talking about it and word gets back to your manager. But it can be helpful to talk over the situation with one trusted friend or colleague to get perspective and to air your own thinking. You may rehearse what you want to say and your friend might, for instance, point out where you sound defensive or insincere.

Remember that your boss has more going on than just your battle. Your boss has normal reactions to stress and disappointment just like anybody else. She may be reacting disproportionately for reasons you can’t see in the moment. When I yelled at the reporter it was because I saw even longer days and nights of stress ahead of me until I came up with another article for the issue. But she probably didn’t realize that. Try to see the issue from your boss’s perspective.

Own the mistake. If you’ve done something to trigger your boss’s ire, take the high road. If you make a mistake, ‘’own it,’’ advises communication expert Holly Weeks, author of Failure to Communicate: How Conversations Go Wrong and What You Can Do to Right Them. Even if it’s not entirely your fault, your boss will appreciate you taking responsibility. My reporter was working on a very tricky piece. It wasn’t entirely unreasonable to be late and I’d pushed her to finish sooner than she wanted to. Still, a sincere apology like, ‘’I’m sorry I let you down,’’ would’ve gone a long way.

Offer a solution. If you can help solve the problem, do so. You may not have a ready-made solution at the time, so consider taking a break in the conversation, reflecting on what happened and how you make it better, and then come back to it with fresh eyes, Weiss advises. “Some conflicts take multiple iterations to resolve,’’ he says. “Success may come in small increments.’’

Re-align with your boss. Make a point of getting on the same page with your boss. Tell her you’d like to avoid disappointing her again and ask her to discuss her priorities with you. If making a deadline is a top priority, you’ll know to communicate with her long before that’s in jeopardy. If not being surprised by bad news matters most, knowing so will let you avoid finding yourself in a similar predicament to my reporter.

It might not be you. If you have no idea what you did to trigger your boss’s ire – and you think maybe you aren’t at fault – still make a point of checking in with her. Your boss will appreciate that you’re making the effort to get on the same wavelength. In that conversation, your boss may let her guard down and explain the stress that she’s under, helping you better understand her challenges. But be careful to listen, rather than complain about her anger. Your goal is to open the doors to candid conversation. Either way, your boss will respect your having the courage to talk with her about how to make things better. On the other hand, your boss’s anger may not be justified. It’s not unusual for a manager to blow up at the last person in a chain of bad news. You can’t always know what caused your boss to lose her cool. It’s possible there wasn’t a good reason she lost her temper and she doesn’t have much to say about it — you were just the unlucky recipient. If that’s the case, try to put it behind you. If you keep the incident in perspective, it won’t color an otherwise good relationship.

Fortunately for both of us, I ended up repairing my relationship with the reporter, enough to convince her to join the next magazine I went to. And eventually, we were able to laugh about the incident. Like me, your boss may be embarrassed by the way she handled the situation. And like me, your boss would appreciate your working a little bit harder the next day to set things right. “Conflict is inevitable and conflict is not bad,’’ Weiss says. “We need to manage differences every day. Sometimes the best we can do is build understanding.’’

Why It’s Getting Harder to Find a Small Home in the U.S.

The proportion of big homes being built in America has increased: Mega-houses of 4,000 square feet and more accounted for more than 9% of new homes last year, compared with 6.6% in 2005, and 3,000-to-4,000-square-foot houses made up 21.7% of new homes, up from 15.6%. Meanwhile, dwellings of 1,400 square feet or less made up just 4% of the new-home total, down from 9%, according to CNN. Yet many young people are closed out of the home market because of high prices, difficulties getting mortgages, or student-loan debt.

The Digital Opportunity Staring Credit Cards in the Face

Credit card companies could be doing a much better job of saving us from ourselves.

It’s well known that very few consumers are familiar with the terms of their credit card agreements and that even fewer are aware of those terms’ implications. Pop quiz: What are your favorite card’s interest rate and fees? If you were to charge $1,000 to it and make only the minimum payment each month, how long would it take you to pay it off?

We couldn’t answer those questions either. This lack of awareness can get people into deep trouble. Without realizing what they’re doing, consumers can quickly amass huge, expensive debts, and the consequences can be far-reaching. Recent history has demonstrated the dangers posed to the economy as a whole by poorly understood financial products.

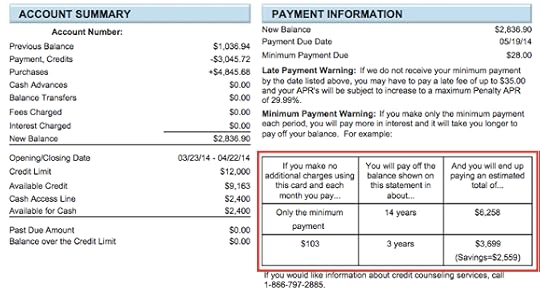

That’s why Congress has been requiring credit card companies to be more transparent. For example, the 2009 CARD Act stipulated that each monthly statement include a “minimum payment warning” spelling out how much time and money it would take to pay off a card by sending in just the minimum. Here’s an example of such a disclosure, which shows the high long-term cost of accumulating credit card debt (in red):

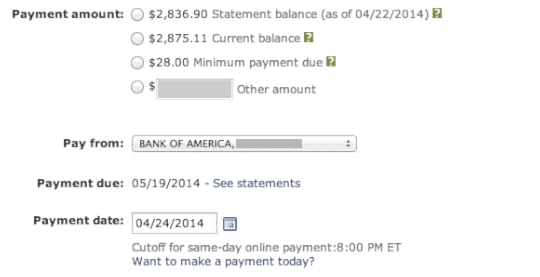

But this disclosure policy and others like it are designed for a world that’s rapidly disappearing: that of paper statements and postal mailings. Although consumers are going paperless in droves, a customer paying a credit bill online via a PC or a mobile app can almost always do so without ever being shown the minimum payment warning. Here’s what a typical online payment page looks like on a computer screen:

To see the minimum payment warning, a customer would have to find and download an electronic version of the paper statement.

Although the federal legislation doesn’t require it (the law focuses on monthly statements, which are central to the paper-statement world), credit card providers should post the warning where it can be easily seen. If a disclosure is important enough to be on the first page of a paper statement, it should be on the corresponding online payment page and mobile-app screen. But there’s a bigger point: The credit card companies are missing a valuable opportunity to make consumers smarter about debt.

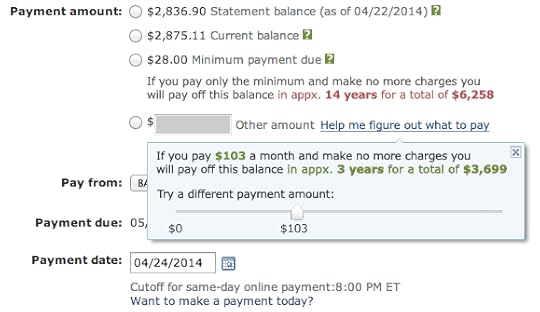

Unlike a paper statement, a web site can turn a data point into a function that aids decision making by spitting out dynamic, personalized information. People are already—and increasingly—using such online tools to help translate personal data into good decisions. FitBit, for instance, takes complicated health goals such as weight loss and distills them into something as simple as tracking the number of steps you take each day. The tool works because it makes a difficult task much easier to manage. Other tools tell us which foods are healthiest, which driving route is fastest, and which new TV series will hook us.

Apply that concept to financial decision making, and you can see how effective it might be for credit card companies to turn the minimum payment disclosure into an online tool. Consumers could use it to see the ramifications of paying the minimum or any other amount that fits their financial circumstances, like so:

A few credit card companies are beginning to take their online offerings in this direction. Capital One recently launched the Credit Tracker, which allows customers to simulate how financial decisions might affect their credit scores. This is a laudable development, but such tools are incomplete, and hardly an industry norm.

Which brings us to the question of whether the credit card companies want consumers to be smarter about debt. Some would argue that they don’t, that their business model is built on extracting hefty interest payments from us, even if it means driving us and the economy to ruin. Certainly the companies’ decision to follow the letter, but not the spirit, of the CARD Act by leaving the minimum payment warning off of online bill-payment screens suggests a cynical disregard for consumers’ financial welfare.

But improved financial literacy should be in the companies’ interest. In a world where card companies are often perceived as the bad guys, this is a way for a company to differentiate itself as a consumer advocate and build a more engaged, loyal customer base. Sure, such efforts would come at a cost. But the potential upside is large: making consumers smarter about their use of credit and reducing default risk, in addition to building a stronger brand. Credit card companies have an opportunity to present themselves not only as providers of credit but as educators.

And in that role, they need to see the internet’s vast potential as a tool for education as well as for easing the management of difficult things. In fact, there are other tools that card companies could build as well. For example, they often provide customers with end-of-year spending analyses—displaying how much of your expenses went toward gas, entertainment, groceries, and so forth. An online tool could allow customers to set spending goals and benchmark their spending against a set of peers of their choosing, encouraging smart financial decisions.

The internet has opened up consumers’ and corporate leaders’ thinking about the meaning of disclosure. Credit card companies should take a lesson from what other consumer companies have done and truly enter the digital age as leaders in improving financial decision making.

June 10, 2014

Your Work-Life Balance Should Be Your Company’s Problem

Seven out of ten American workers struggle to achieve an acceptable balance between work and family life, reports a new study published in American Sociological Review, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That number has been climbing over time, to a point where employees — especially parents — feel stressed, overwhelmed, and maxed out. In “Changing Work and Work-Family Conflict: Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network,” researchers asked what can be changed in the workplace to address this growing health and productivity problem. They conducted a large-scale experiment in a Fortune 500 company and found that work-family conflicts don’t need to be solely employees’ individual, private troubles, but can be resolved systemically with a little management leadership.

Nearly 700 employees from an information technology department participated in the experiment. These were highly skilled, middle-aged workers with professional and technical degrees. They worked long hours, with over 25 percent logging more than 50 hours per week. Some worked remotely but reported pressure to be visible at the office to demonstrate work and team commitment. The research team randomly assigned these employees to two groups. Those in the “treatment” group were then given greater control over when and where they worked, and more supervisor support for their family and personal lives. The control group’s working conditions remained unchanged.

Over a six-month period, the people in the treatment group experienced a significant reduction in work-family conflict — that chronic sense of being pulled in two different directions. Crucially, employees who were more likely to be vulnerable to work-family conflicts (parents and people with less supportive supervisors initially) benefitted most from the intervention. Parents reported working one hour less per week than non-parents, but others did not have to increase their workloads to accommodate parents. People in the treatment group also reported that they felt they now had adequate time to spend with their families while managing their workloads. Overall, they felt more in-control and less overwhelmed.

For people working every day to balance complicated lives, this might not sound like news — but here’s why it is. This is the first study to offer evidence based on a randomized trial that workplace interventions, such as increased schedule control and supervisor support, can reduce employee work-life conflict. The randomized, experimental method allowed researchers to eliminate competing explanations for their findings — explanations, for example, like lower initial stress or the possibility that some workers quit to take less stressful jobs elsewhere. The study is also the first experiment to change the way people and supervisors work to benefit employees’ work-family balance. By altering factors in entire workplace groups or departments, the research shows that there is a way to move away from “Mother may I?” workplace flexibility — individual accommodations that a person negotiates with his or her boss — and toward systemic change in an organization that benefits all.

Numerous benefits of lowering work-life stress have been documented, in physical health and mental health (including reduced hypertension, better sleep, and lower consumption of alcohol and tobacco), as well as decreased marital tension and better parent-child relationships. So it’s surprising that two other new studies report weakened company commitment to employees working flexibly. While more than 8 in 10 employees in new survey from the Flex+Strategy Group cited negative impacts on worker loyalty, health, and performance when a company does not permit work-life flexibility, almost half of the respondents sensed ambivalence and declining commitment to it from their employers. Further, a Boston College study found that, while telecommuting and flexible hours are often negotiated between individual employees and their supervisors on an as-needed basis, companies have cut back on some critical work-life balance options like reduced hours, part-time work, job sharing, and paid family leave.

What employees sense about their managers’ and companies’ commitment to work-family-life balance reflects the organizational culture and its leadership. Returning to the American Sociological Review study, the people in the experimental group who were given more control over when and where they worked, almost doubled their average hours of work at home (from 10 to almost 20 per week). These technology workers had the tools to telecommute prior to the workplace experiment, but they either had not been given discretion to do so or had not felt comfortable doing so. The “permission” granted by the experiment freed workers to think about new ways of working, and many did so. The experiment also “unfroze” managers from old ways of doing things.

In the end, adjustments in management thinking about when and where work gets done, and about support for employees’ lives outside work, led to the work-life holy grail: design of system-wide flexibility (to relieve pressure for people who need it), without burdening those working conventionally, and without requiring individual workers to figure out alone how to balance everything.

In Defense of Routine Innovation

Almost every discussion of innovation today inevitably turns to the topic of “disruption.” Academics write about the power of disruptive innovation to transform one industry after another. Consultants have set up practices to focus specifically on helping companies become disruptive innovators. Venture capitalists tout their latest investments as potential disruptors. Even executives of large corporations talk about the need to make their behemoths into nimble disruptors.

It is, of course, with good reason that disruptive innovation draws our attention. Disruptive innovation — generally defined as innovation that fundamentally transforms the way value gets created and distributed in an industry — has the promise to catapult start-ups into multi-billion-dollar enterprises and topple seemingly untouchable giants, all at the same time. The promise of becoming the next Google, Amazon, or Apple (and the threat of becoming the next, Kodak, Polaroid, or Barnes & Noble) is certainly enough to make us take notice.

Yet all the excitement about disruptive innovation has blinded us to one simple but irrefutable economic fact: The vast majority of profit from innovation does not come from the initial disruption; it comes from the stream of routine, or sustaining, innovations that accumulate for years (sometimes decades) afterward. An innovation strategy has to include both. Let’s examine a few examples.

Intel is certainly one of the great disruptors of all time. Its microprocessor fundamentally altered the structure of the personal computer industry. Yet, its strategy for almost three decades has largely been that of a sustainer, not a disruptor. Its fortunes have been built upon its successes in pushing the technological frontier of the microprocessor. But its essential value proposition — a higher-performing, high-margin product — has not changed.

Let’s take the introduction of the x386 in 1985 as the starting point for the sustaining strategy (although one might argue that the x386 was itself just a sustaining innovation, relative to earlier generations). How has this strategy worked? Well, since 1985, Intel has generated cumulative operating income before depreciation of $287.4 billion.

Is Intel’s growth slowing today? Sure. Is it facing threats today from companies that are making chips better suited to mobile computing? Absolutely. Might it decline in the coming decade? Certainly a possibility. But, how many companies out there (or their investors) would pass up the opportunity to have generated close to three hundred billion in cash?

Another example is every innovation pundit’s favorite company to criticize today: Microsoft. Again, the company has its origins as a disruptor. But for much of its history, Microsoft has been an incredible sustainer. It has built and defended its competitive position by reinforcing its Windows/Office franchise. Its specific tactics have evolved over time, but the basic strategy has remained the same.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact point that Microsoft became a sustainer because it has been a sustainer for so long. Let me be generous to it and take the introduction of Windows 3.1 in 1985 as the transition point. (Many will argue, correctly, that there was not much novel about Windows and that, Microsoft did not really do anything ”disruptive,” in the true sense of that word, since the introduction of DOS). Since 1985, Microsoft has generated $325 billion in operating profit cumulatively before depreciation. Not bad for a mere sustainer.

Is Microsoft’s growth slowing? Absolutely. Has it missed out on really key growth markets like search? Undeniably. Does Linux threaten it in corporate servers? Big time. Is the move toward mobile a potential disruptor for Microsoft? Certainly. Like Intel, these are challenges the company must navigate, but how many companies in corporate history have earned $325 billion over three decades? None as far as I can tell.

Then there’s Apple. The iPhone has got to be the single most successful consumer electronics product in history. Since 2011, Apple has generated $150 billion in cash flow, much of that from the iPhone. But was the device disruptive? There were plenty of smart phones and PDAs around long before the iPhone (the Palm Treo, Nokia 9000, etc.). Why did the iPhone succeed? The answer is pretty simple: It was better. It was better designed aesthetically and functionally. It was beautiful and far easier to use than the alternatives. And later, with the opening of the Apps Store, the iPhone became a much more versatile device.

There was no big disruption. The iPhone did not change the value proposition of the business; it did not create a new market or enter an existing market with a low-end alternative (a classic disruption strategy). The idea behind the App Store — allowing and making it easy to install third-party software on a device — has been around since the beginning of the computer industry. The iPhone has been extraordinarily successful, but it’s hard to argue that it was “disruptive.”

My intention is not to diminish or dismiss disruption. But there is far more to the innovation game than disruption. If you disrupt and can’t sustain, you don’t win.

There are many examples of initial disruptors in an industry that did not sustain their advantage because they were unable to rapidly build upon and improve their initial design. EMI invented the CAT scanner but was crushed by GE, which brought to bear its superior engineering experience and distribution in diagnostic imagining. There were dozens of early personal computer manufacturers in the late 1970s, but most of them failed after IBM entered the market. The early internet search companies (e.g., Lycos) were surpassed by Yahoo, which itself got crushed by Google because it had a far superior search algorithm. Palm and Nokia lost out in smartphones because they failed to win at this brutally competitive game of rapid evolutionary (sustaining) innovation.

In creating an innovation strategy, managers should strive to achieve the optimal balance between disruptive and sustaining efforts. There is no magic formula. Young start-ups are not going to beat an Apple or Google at its own game. They need to find an alternative value proposition, and disruptive strategies are likely the only route there. (This is why it makes sense for venture capitalists to obsess about disruption).

But once a company is established, innovation strategy means understanding how to leverage distinctive existing strengths to generate value and capture value. It means understanding how your repertoire of R&D skills, intellectual property, operating capabilities, relationships, distribution channels, and brand can protect and extend the value from innovation.

Playing to your strengths is a fundamental principle of strategy, and applies to innovation as well. Of course, there is a trade-off — another fundamental principle of strategy. If you play to your strengths, you will exclude certain options (Apple is probably not interested in putting Android on its phones anytime soon). Sometimes, with 20-20 hindsight, excluding a particular option turns out to be very costly. But management, unlike academic research, is not practiced with 20-20 hindsight.

Strategic thinking about innovation requires carefully understanding and evaluating the risks and benefits of leveraging existing capabilities and resources. It certainly does not mean allowing your existing resources to drag you into oblivion as the competitive landscape changes. But neither does it mean blindly observing the often-repeated mantra: “You should eat your own lunch before someone else does.” Sometimes, your own lunch is pretty good and the right strategy may be to protect and extend it as long as possible. A company that is a great sustaining innovator has no reason to be ashamed.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Customer Complaints Are a Lousy Source of Start-Up Ideas

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

Start with a Theory, Not a Strategy

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

Negotiating Is Not the Same as Haggling

There’s a popular misconception that in a negotiation you can either “win” or preserve your relationship with your counterpart — your boss, a customer, a business partner — but you can’t do both. People assume they need to make a choice between getting good results (by being hard and bargaining at all costs) or developing a good relationship (by being soft and making concessions to build the relationship). Thinking that way is dangerous, however, because you need both: You have to be able to stand firm and maintain important relationships.

Too often, a typical negotiation goes something like this:

Party 1: Here’s what I want.

Party 2: Here’s what I want.

Party 1: OK, I’ll make this small concession to get closer to what you want. But just this one time.

Party 2: OK, since you did that, I’ll also make a small concession. But just this one time.

Party 1: Well, that was the best I can do.

Party 2: Me too.

Party 1: I guess I need to get my boss involved (or find someone else with whom to negotiate).

Party 2: I may need to walk away, too.

Party 1: Maybe there’s something I can do. What if I make this additional concession?

Party 2: That would help.

Party 1: I’ll need to get a concession from you then.

Party 2: OK. What if we agreed to split the difference?

Party 1: It’s a deal.

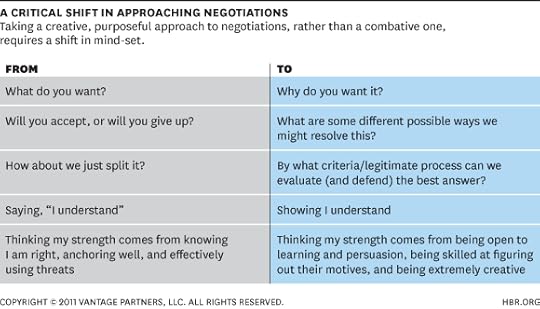

Sound familiar? This is a common approach, often called “positional bargaining.” People believe that if they go into the negotiation looking stern and unmovable, and then make small planned concessions and not-so-thinly veiled threats along the way, they’ll have more influence and get the results they want. But in my view, that isn’t a path toward negotiation that gets you what you want. It’s simply a haggle, a concessions game that forces you (and your counterpart) to compromise.

Positional bargaining isn’t all bad. It can be quick and efficient. It requires little preparation other than knowing what your opening offer is, what concessions you’re willing to make, and any threats you might use. And in the end, it always feels like you got something, because if your counterpart played his role, then he conceded as well. In fact, positional bargaining works great when you are negotiating simple transactions that have low stakes and you don’t care about your ongoing relationship with the other party (think about agreeing on a price for that leather couch off Craigslist). But that doesn’t describe the majority of situations.

In almost all business negotiations — resolving a conflict with a customer, convincing others of a change in policy, agreeing on a budget for next year, for example — there is a lot more at stake, and chances are strong that you’ll need to continue to work with the other party going forward. If you were to try to use positional bargaining in those situations, you wouldn’t get impressive results.

That’s because there are serious downsides as well. Positional bargaining rewards stubbornness and deception; it often yields arbitrary outcomes; and it risks doing damage to your relationships. Most importantly, it causes you to miss the opportunity to get more value out of the negotiation than you originally expected. In other words, you won’t be creative and find ways to expand the pie because you’ll be so focused on exactly how to divide it up.

Perhaps most dangerously, there is an underlying assumption in this approach that you’re in a zero-sum game: If you gain something, the other party has to give up something in return. In the vast majority of negotiations we’ve worked on, there is always more value to be created than originally thought. The pie is rarely — probably never — fixed.

To negotiate more effectively, you need to shift your approach away from this combative and compromising approach and toward a more collaborative one. The figure below shows how to reframe key questions about the negotiation with this approach in mind. For example, instead of asking yourself, “What am I willing to give up?” you might think more creatively and wonder, “What are different ways we can resolve this?” This helps ensure you aren’t shrinking the pie but expanding it.

This shift leads to an approach where two parties come together to jointly solve a problem — decide on a contract, create the parameters of a new job, or delineate the conditions of a partnership. Together they dig to fully understand each other’s underlying interests, invent options that will meet everyone’s core interests (including those of people not even in the room), discuss rational precedent, and use external standards to evaluate the possibilities — all while actively managing communications and building a working relationship.

At first read, this may sound like a “soft” approach to negotiation. In fact, it is just the opposite: It takes discipline and toughness to truly get creative and to apply sound decision-making criteria. Taking a joint problem-solving approach does not require, or even condone, sacrificing your own interests. It is about being clear about why you want what you want (and why the other party wants what they want) — and using that information to find a high-value solution that gets you both there.

The benefits of this approach include better solutions, improved working relationships, greater buy-in and commitment, and more successful implementation of solutions.

Of course, there are drawbacks as well. This approach requires more preparation, deeper skill, and real discipline. You may feel uncomfortable at times as you use what may be an unconventional approach. Your counterpart might be uncomfortable as well. She might even interpret your openness to collaboration as weakness and think she can take advantage of you. But if you take a disciplined approach to negotiation, she won’t. In fact, you’ll shape the negotiation and get the results you seek, and often much better ones than you ever expected..

This post is adapted from the forthcoming HBR Guide to Negotiating .

Does Race or Gender Matter More to Your Paycheck?

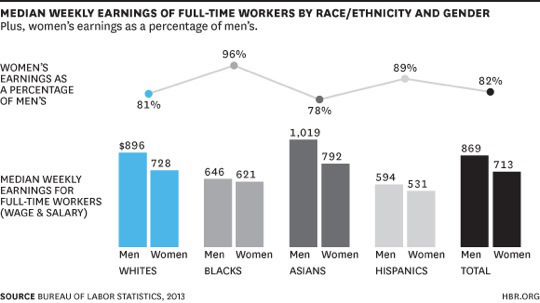

In 2013, American women made 82 cents to every dollar a man made and 80 cents to every dollar made by a white male; up from 79 cents and 77 cents, respectively, in 2012, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. However, white and Asian people, regardless of their gender, make more than blacks and Hispanics – regardless of their gender.

So when it comes to pay gaps, do race and ethnicity trump gender? I set out to find out.

First I explored weekly median earnings by age as well as gender and race/ethnicity. Younger workers, aged 16 – 24, are more likely to be in minimum wage jobs because of lack of experience or less education; if one demographic group had a remarkably younger workforce, that would skew their average income lower. In 2013, men and women had the same percentage of workers between 16 – 24 years of age (8.7%) – but the percentage varied much more widely by race/ethnicity. Hispanics, the group with the lowest wages in the chart above, have the highest percentage (12.4%) of workers between 16 – 24 years of age. Asians, who have the highest earning power, have the lowest percentage (6.5%) of workers between 16 – 24 years of age.

But the correlation between age and earning power breaks down when you look at whites and blacks. The white workforce is younger than the black workforce — 8.8% of their full time workforce is between 16 – 24 years of age compared with blacks at 8.0% — and yet whites earn considerably more. (In addition, it’s worth noting that the unemployment rate for black youth is 26.6% almost double the unemployment rate of white youth at 13.5%.). While age may play a role in the lower weekly median earnings for Hispanics, it does not explain the lower median wage for blacks.

Next I turned to education to help sketch a fuller picture. According to census data, educational attainment is lower for Hispanics and blacks; but comparable for men and women. So at first blush, education appears to explain the pay gap between the races (though not, importantly, the genders).

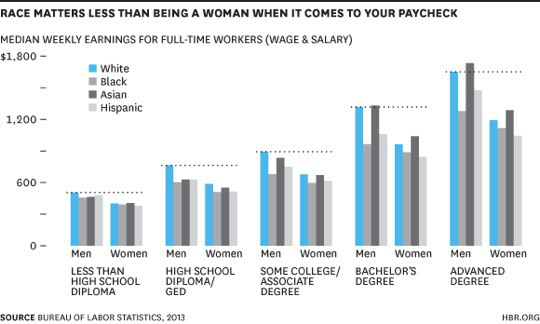

To see how much education matters to the pay gap, I held education levels constant across both race and gender and excluded workers aged 16-24 (who may not be finished with their schooling). The results are visualized below. Greater education does increase earnings, however, education is not “the great equalizer” it has often been made out to be. Earners with the least amount of education have the smallest pay gap – lack of an education affects everyone about equally, resulting in poverty. But having an education has the most benefit for men, especially white men.

Only now was I starting to get an accurate picture of the wage gap in America – or rather the wage gaps, plural. The oft-used simple chart at the top of this post provides a misleading picture of the status of white women on the earnings pyramid. This second chart shows how men, regardless of race or ethnicity, earn more than women of any race when education level is held constant, with one exception – Asian women. Asian women with bachelor’s and advanced degrees are the only women who make more than one group of men–black men, who earn the least in comparison to their male counterparts at every level of education.

This chart exposes one other important myth: that companies have to pay more for talented women of color. In discussions of affirmative action cases and throughout my career, I have heard both from right-wing bloggers and middle-of-the-road human resources professionals that a premium is paid to attract and retain women and minority talent and especially, women of color. The central argument is that because there are assumed to be so few “qualified” candidates who are both female and nonwhite – and because companies can count women of color towards multiple diversity targets — competition for those candidates means they end up with significantly higher salaries. Setting aside the question of whether there is, in fact, a shortage of qualified women of color, it should by now be obvious that those women aren’t getting paid a premium. In fact, black and Hispanic women vie for last place on the earnings pyramid at every level of education, and the gender pay gap actually increases with higher education for black, white, and Hispanic women. Routinely, when pay equity analyses are done for corporations, the employees whose actual salaries are greater than two standard deviations higher than their predicted salary (based on job-related variables such as market value, time served, and performance ratings) are white men.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers