Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1407

June 19, 2014

How to Spend the First 10 Minutes of Your Day

If you’re working in the kitchen of Anthony Bourdain, legendary chef of Brasserie Les Halles, best-selling author, and famed television personality, you don’t dare so much as boil hot water without attending to a ritual that’s essential for any self-respecting chef: mise-en-place.

The “Meez,” as professionals call it, translates into “everything in its place.” In practice, it involves studying a recipe, thinking through the tools and equipment you will need, and assembling the ingredients in the right proportion before you begin. It is the planning phase of every meal—the moment when chefs evaluate the totality of what they are trying to achieve and create an action plan for the meal ahead.

For the experienced chef, mise-en-place represents more than a quaint practice or a time-saving technique. It’s a state of mind.

“Mise-en-place is the religion of all good line cooks,” Bourdain wrote in his runaway bestseller Kitchen Confidential. “As a cook, your station, and its condition, its state of readiness, is an extension of your nervous system… The universe is in order when your station is set…”

Chefs like Anthony Bourdain have long appreciated that when it comes to exceptional cooking, the single most important ingredient of any dish is planning. It’s the “Meez” that forces Bourdain to think ahead, that saves him from having to distractedly search for items midway through, and that allows him to channel his full attention to the dish before him.

Most of us do not work in kitchens. We do not interact with ingredients that need to be collected, prepped, or measured. And yet the value of applying a similar approach and deliberately taking time out to plan before we begin is arguably greater.

What’s the first thing you do when you arrive at your desk? For many of us, checking email or listening to voice mail is practically automatic. In many ways, these are among the worst ways to start a day. Both activities hijack our focus and put us in a reactive mode, where other people’s priorities take center stage. They are the equivalent of entering a kitchen and looking for a spill to clean or a pot to scrub.

A better approach is to begin your day with a brief planning session. An intellectual mise-en-place. Bourdain envisions the perfect execution before starting his dish. Here’s the corollary for the enterprising business professional. Ask yourself this question the moment you sit at your desk: The day is over and I am leaving the office with a tremendous sense of accomplishment. What have I achieved?

This exercise is usually effective at helping people distinguish between tasks that simply feel urgent from those that are truly important. Use it to determine the activities you want to focus your energy on.

Then—and this is important—create a plan of attack by breaking down complex tasks into specific actions.

Productivity guru David Allen recommends starting each item on your list with a verb, which is useful because it makes your intentions concrete. For example, instead of listing “Monday’s presentation,” identify every action item that creating Monday’s presentation will involve. You may end up with: collect sales figures, draft slides, and incorporate images into deck.

Studies show that when it comes to goals, the more specific you are about what you’re trying to achieve, the better your chances of success. Having each step mapped out in advance will also minimize complex thinking later in the day and make procrastination less likely.

Finally, prioritize your list. When possible, start your day with tasks that require the most mental energy. Research indicates that we have less willpower as the day progresses, which is why it’s best to tackle challenging items – particularly those requiring focus and mental agility – early on.

The entire exercise can take you less than 10 minutes. Yet it’s a practice that yields significant dividends throughout your day.

By starting each morning with a mini-planning session, you frontload important decisions to a time when your mind is fresh. You’ll also notice that having a list of concrete action items (rather than a broad list of goals) is especially valuable later in the day, when fatigue sets in and complex thinking is harder to achieve.

Now, no longer do you have to pause and think through each step. Instead, like a master chef, you can devote your full attention to the execution.

June 18, 2014

Case Study: Is It Ever OK to Break a Promise?

Editor’s note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

To: Patrick Fishburn, Asst. Manager, Operations

From: Sameer Hopskin, Asst. Manager, Operations

Date: January 20, 2012 20:41

Subject: RE: lunch today?

thanks for the burritos—and the advice. i’m totally convinced i need to go for the MBA and move into the business side of things. i’ve learned a lot here, but i can’t be a college-educated factory hand forever! but man the tuition is crazy expensive!

To: Ioana Romana, VP Operations

From: Sameer Hopskin

Date: January 23, 2012 14:18

Subject: Meeting with Mr. Baba

Dear Ioana,

I want to ask a big favor: I’d like a meeting with Mr. Baba to discuss the possibility of the company sponsoring me in an MBA program. I’m sure that I could add a lot of value if I had more business training.

In my time at BABA, I’ve had four promotions and consistently high evaluations. I can do the job of just about anyone in the factory and can work most of the software the engineering guys use. But I feel pretty far behind on the business side of things.

Please help me get a meeting with Mr. Baba. If he agrees to sponsor my MBA, I’ll be able to bring so much more to this company.

Sincerely,

Sameer

To: Sameer Hopskin

From: Ioana Romano

Date: January 23, 2012 14:42

Subject: RE: Meeting with Mr. Baba

Hi Sameer,

As I mentioned, Anil doesn’t think it makes sense for us to send people off to do MBAs. He thinks it’s best to have our employees “get their hands dirty” and give them the training they need here.

He’s also worried that they’ll leave the company if they get “fancy credentials.” Manufacturing is not the most glamorous business, and MBA recruiters are known for tempting people into more “prestigious” careers. Anil is big on commitment. He still talks about one senior manager—a man he’d spent years teaching the business to—who left a while back after taking an executive education program and being wooed away by one of our competitors.

I’ll try to get you a meeting, but I wanted to give you this background first. Anil started this company 20 years ago, and it wasn’t easy to get it where it is today. He’s really a committed boss, and he expects the same from his employees.

Regards,

Ioana

To: Anil Baba, CEO

From: Ioana Romano

Date: January 23, 2012 17:52

Subject: Sponsoring an MBA

Hi Anil,

Sameer Hopskin has worked for us for five years. He joined just after completing his BS in engineering and has had an excellent progression with the company. He’s part of my operations team now, and he hopes to transition to a management position. I think his real goal is to work more closely with you at headquarters?

He’s hoping we’ll give him a one-year leave of absence to do an MBA, and that we’ll cover his tuition.

I know you don’t like this kind of thing in general, but I think you should meet with Sameer. He’s a real asset to us. Will you do that for me?

Respectfully,

Ioana

To: Ioana Romano

From: Anil Baba

Date: January 23, 2012 18:37

Subject: RE: Sponsoring an MBA

Fine. Tell him to come to my office tomorrow at 8 a.m. sharp.

To: Ioana Romano

From: Sameer Hopskin

Date: January 24, 2012 10:17

Subject: Never Give Up

Dear Ioana,

Thanks for arranging for me to meet with Mr. Baba. I really appreciate it.

Unfortunately, Mr. Baba was not keen on my idea. I know he is a very successful man, but I think he may not appreciate fully what I could add to this company with some formal business training. The landscape is getting more competitive and complex. Surely the company could benefit from a more contemporary perspective.

I know Mr. Baba really respects you. I would really be grateful if you would talk to him again. I am a loyal employee. Please help me get Mr. Baba to understand that.

Thanks in advance,

Sameer

To: Ioana Romano

From: Anil Baba

Date: January 29, 2012 05:02

Subject: RE: Sponsoring an MBA

You’re right about that Sameer kid. He reminds me of me. If he works hard for a few more years I can see him on my team. See what we can do to keep him around.

To: Anil Baba

From: Ioana Romano

Date: February 3, 2012 12:17

Subject: RE: RE: Sponsoring an MBA

Dear Anil,

I talked with HR, and we can structure a contract so that Sameer Hopskin will be obligated to work here for at least three years after finishing his MBA. If he leaves beforehand—and Legal says there’s nothing we can do to make that impossible—he’ll be required to repay us for his tuition.

Sameer is a good kid, and I think he’s right about the advantages of having a few more MBAs around here. This investment might not look so bad if you consider how much we paid those consultants last year.

Should I push this forward with HR?

All the best,

Ioana

To: Ioana Romano

From: Anil Baba

Date: February 3, 2012 12:27

Subject: RE: RE: RE: Sponsoring an MBA

Get HR to draft the contract, and have that guy with the Russian name in Legal look it over. He doesn’t miss a thing.

If this kid comes back in two years working for one of those consulting shops and charging us $10,000 a day, we’ll pay him out of your salary.

To: Sameer Hopskin

From: Ioana Romano

Date: February 6, 2012 13:42

Subject: RE: Never Give Up

Sameer,

I talked to Anil, and he’s open to sponsoring your MBA. I also talked with HR about how to formalize this. The deal is the company would pay your tuition and commit to a position (with a promotion) upon completion of the degree. You would be obligated to work here for three full years; otherwise, you would have to repay the tuition. It’s a pretty standard setup—more or less what the consulting firms do.

That’s the legal part of it. But I don’t want to offer you this unless we settle something more important. As you know, Anil’s main worry is that you won’t return after your MBA. It’s not about the money. It’s about the precedent. If you set a good example, Anil may see value in sending more of our people to get their MBAs, something I know several others, including your friend Patrick, are interested in. But if you violate his trust, no one else will get the chance. You have to promise that you’re going to bring all your new knowledge and skills back to this company.

Sincerely,

Ioana

To: Ioana Romana

From: Sameer Hopskin

Date: February 6, 2012 13:49

Subject: RE: RE: Never Give Up

Dear Ioana,

Thank you so much. I am fully committed to BABA. I will study hard and come back to really help this company grow.

Faithfully,

Sameer

To: Sameer Hopskin

From: Patrick Fishburn

Date: February 6, 2012 20:41

Subject: RE: MBA here I come

dude that’s amazing! you’re totally paving the way for the rest of us!

To: Raji Hopskin

From: Sameer Hopskin

Date: May 12, 2013 21:37

Subject: RE: RE: Back to School

Mom,

Tell dad I gave Mr. Baba the bottle of whisky he sent. Mr. Baba asked for your address; so I assume he’ll be sending you a thank-you note. He’s old school just like dad. Please thank dad again and tell him I did look Mr. Baba in the eye when I shook his hand today. (By the way, I don’t need any more lessons in “how to be a man.”)

Love,

Sammy

To: Sameer Hopskin

From: Lucia Baltimore, HR

Date: August 15, 2012 09:49

Subject: Tuition Payment Confirmation

Dear Sameer,

I confirm receipt of the signed contract. We have made a bank transfer, and your tuition is paid. Regarding your last question: Yes, your medical insurance will remain active. There is no cost to you.

See you in a year.

Lucia Baltimore

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Patrick Fishburn

Date: June 6, 2013 20:16

Subject: catching up

dude, how is b-school wrapping up? things are good here. they gave me your old job, and i’m learning a lot. i’m psyched to do an mba myself. peace, p

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Dana Knight, Principal, Zeisberger Assoc.

Date: June 8, 2013 07:12

Subject: Employment Opportunity

Mr. Hopskin,

I work with Zeisberger Associates, an executive search firm, and we represent a client who is interested in your profile. It is a startup in Silicon Valley with some serious VC backing. Your background in engineering and manufacturing, together with your stellar MBA performance, is really appealing to the company.

Can we arrange a meeting to discuss?

Cheers,

Dana Knight

To: Dana Knight

From: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

Date: June 8, 2013 07:22

Subject: RE: Employment Opportunity

Dear Ms. Knight,

I have class all day, but I can talk this evening after 6.

Sorry to ask, but how did you find me?

Thanks,

Sameer

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Dana Knight

Date: June 8, 2013 07:25

Subject: RE: RE: Employment Opportunity

Sameer, we looked through your school’s CV book. Your profile is clearly the best fit for this job. Trust me, it’s a very cool company. Silicon Valley, amazing office with a tennis court, gourmet lunches, jazz playing all the time, etc. I would so work there! Talk at 6. Cheers, Dana

To: Dana Knight

From: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

Date: June 8, 2013 19:21

Subject: RE: RE: RE: Employment Opportunity

Dear Dana,

I really appreciate your time today. The job does sound perfect. As I said, however, my company is sponsoring me, and I promised my boss I would return. I wouldn’t be here without their support. I need to think about this.

Thanks again,

Sameer

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Dana Knight

Date: June 14, 2013 19:26

Subject: RE: RE: RE: RE: Employment Opportunity

They loved you! But their investors are on their Board, so management is being pushed to fill critical vacancies ASAP. Sorry but they want a decision quickly. You said your contract requires you to pay back your tuition. I can try to arrange for WeDiggIt to cover those costs. As long as you honor the contract, you’re fine. Cheers.

From: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

To: Raji Hopskin

Date: June 14 2013 23:47

Subject: RE: RE: Tough Decision!

Mom,

I still can’t figure out what to do. I feel really bad about all this. I didn’t look for it. They came to me! I know how you and dad feel, but the new job is an unbelievable opportunity—with a salary twice what I’d be making at BABA. When I promised Ioana I’d go back, there’s no way I could have predicted this. Please make sure dad knows that the world is different these days. Things are more competitive now.

Love,

Sammy

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Ioana Romano

Date: June 15 2013 18:22

Subject: RE: Headhunter

Sameer,

That’s pretty common. Headhunters have approached me several times in my career. I appreciate the heads-up. (No pun intended.) I presume you told them you already have a job?

See you soon,

Ioana

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Lucy Vinapola, HR Manager, WeDiggIt

Date: June 22 2013 10:14

Subject: Offer of Employment

Dear Mr. Hopskin,

I have attached your offer, with an annual base salary of $146,000 and a sign-on bonus of 50% of your MBA tuition. Please let me know if you have any questions.

Yours,

Lucy Vinapola

To: Sameer Hopskin (MBA)

From: Ioana Romano

Date: June 23 2013 18:22

Subject: RE: RE: RE: Headhunter

Sameer,

The job sounds fantastic. I get it. I just want to remind you that you gave us your word you would come back. I want the person I supported then to make this decision, the one who swore to me he’d help the company that helped him. I trust you’ll do the right thing.

Sincerely,

Ioana

Question: Should Sameer return to BABA or take the WeDiggIt offer?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address

The EU Privacy Ruling Won’t Hurt Innovation

Consumers have a “right to be forgotten” – at least in the EU. Last month, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) classified Google as a data controller and ruled that they must comply with individuals’ requests to remove certain links to personal data. Google has asserted that this will adversely affect innovation, but those claims are premature. The EU’s human rights-centered views have been influencing global standards and privacy practices in the Middle East for decades, and businesses have adapted to more restrictive markets, like China and North Korea, and thrived. The ruling presents opportunities to establish profitable relationships with European clients who desire privacy-based services. Corporations need to see privacy as another market ripe for innovation, one that can yield global profits, because adapting to EU concerns means extending your market reach across the world.

And Europe’s concerns are global concerns. The ECJ ruling has implications for all multinational businesses that handle European data, and it dilutes the “proportionality test,” where businesses claim that the economic effort of deleting personally identifiable data is damaging to their business models. Now, companies need to pay attention to where their clients live (and the jurisdictions that govern them) because they can be held accountable.

Even before the ECJ decision, Europeans felt that they had to balance access to US markets with the risk of EU fines. A lawyer for an EU corporation told me, “When we work with U.S. companies who process our data, we have to put something in our contracts that give us some protection because we know that they won’t be held accountable. We want to participate in U.S. markets, but we know we are exposing ourselves at home.” Officials are even reviewing the Safe Harbor agreement, which enables the transfer of personal data from the EU to companies in the U.S., and pressing for more robust enforcement on U.S. soil. And a new Data Protection Regulation aims to create one centralized law and expand the arm of EU enforcement. If it goes into effect by 2015, the stakes will be even higher. These efforts will pressure European companies to look for U.S.-based providers who can address these concerns. This may keep EU companies from using U.S.-based services, but it also opens a market for companies with healthy privacy systems, since others won’t be able to shield their EU clients from litigation.

The Google case should motivate telecoms and global corporations to integrate privacy into their operational models, instead of treating them solely as issues of compliance. Google has already extended its practices to states outside the EU with similar laws, which (despite the company’s condemnation of the ruling) is an innovation that places Google at the forefront of privacy services. Bing is also following its lead by striving to develop a “right to be forgotten” feature. If other companies establish mechanisms to protect their clients’ private data, they can cater to the more regulated EU markets and rebuild consumer trust at home (it has deteriorated as a result of Snowden’s revelations and growing concerns about U.S.-based cloud computing).

U.S. laws about government surveillance and corporate data ownership likely won’t harmonize with Europe any time soon, but this is an opportunity for companies to maintain competitive advantage and keep up with newer market players. To respond to these changes and make privacy work for profit, consider:

A new market for privacy services. Google already handles a host of removal or review requests from the broadcasting and music industries for IP violations. Now the company is fielding an average of 10,000 individual requests a day through its new online form, and a team must be trained to review them. The economic impact on Google and others has yet to be determined, but it opens a job market for privacy experts. Reputation management companies, which work to bury search engine results, could also offer request services to individuals.

Integrating privacy officers. Privacy is not just about fulfilling legal obligations; it involves understanding telecom systems, regulations, and the operational characteristics of a particular industry. Businesses should take a cue from the intelligence community and make privacy officers more than compliance watchdogs. Train risk assessors to identify sensitive or important data and assess the connections among your security teams and your business models.

Privacy as part of your client relationship. These rulings mirror growing mistrust of how consumer data is managed. Surveys indicate growing American and European unease over how companies gather and use consumer data, their role in sharing personal data with governments, and the transfer or sale of data to third parties without consent or knowledge. Consumers increasingly believe that companies see them merely as data fodder. Treat their private data with respect, and you will attract loyal new customers. Firms that process data already provide tailored services for their clients, so it makes sense to include European privacy protection as another customized service. Hire data security experts and have them work with privacy officers to construct systems that secure data, use it responsibly, and test these mechanisms regularly. Embed data protection into your company’s culture, and involve your clients in the process. Communicate how you protect them in clear and concise language, and invite feedback.

Failure to take privacy seriously can put you at risk of fines or litigation, but the worse case scenario involves negative publicity equating your company with a lack of concern over personal information (e.g. Target and Neiman Marcus). The Google ECJ case is an opportunity to strengthen relationships between clients and consumers by reconsidering how their data is managed. The winners of the digital age will be those who see privacy as an investment that secures profits and opens up privacy markets across the globe.

How to Kill Quarterly Earnings Guidance

Quarterly earnings guidance has outlived its usefulness.

There are instances when it might be perfectly legitimate and value enhancing to issue earnings guidance in an effort to inform the market about material disruptions, shifts in the business model etc., but on the whole, the practice is not a helpful way of building a sustainable business that is geared to succeed in the long-term.

By now it is well understood that the short-term focus by shareholders on quarterly earnings can impair firms’ ability to create long-term value. Research by our organizations — the Generation Foundation and KKS Advisors — suggests that the costs of regularly issuing earnings guidance, either quarterly or annually, may well outweigh the benefits, and likely contributes to this short-term focus. Earnings guidance attracts investors focused on the short-term, and tempts executives to engineer quarterly earnings to meet the expectations that they have issued. At a macro level, there is evidence that it negatively influences analysts’ reports, thereby distorting the market.

Despite these costs, many firms feel tethered to the practice, worried that abandoning the practice might send a negative signal to the market. But these concerns can be mitigated with the proper strategy for shifting away from earnings guidance, and by replacing it with integrated reporting.

If you want to move away from this practice there are a few, clearly defined steps the CEO or CFO can take (importantly, the message should come from one or the other of those executives to highlight the company’s conviction in this decision):

Clarify that stopping guidance is not a sign of increased uncertainty or economic conditions, rather an effort to establish practices that emphasize long-term value creation.

Reinforce step one by confirming guidance numbers for the same period and issue one last set of guidance numbers for the following period when you announce your decision to end issuing earnings guidance.

Highlight that your board agrees with the decision, suggesting that this is a strategic, thoughtful choice that has received broad support internally.

Communicate a clear five-year strategic plan defining financial and sustainability milestones.

Announce the adoption of integrated reporting as it not only enhances the information environment of the firm but it also serves as a disciplining mechanism to ensure that the company has a long-term sustainable strategy. Integrated reporting is the process of communicating how the firm is using different forms of capital, human, financial, natural, physical, intellectual, and social to create value over the short, medium and long-term. Integrated guidance that intends to inform market participants about future changes in the value of these capitals can further improve the information environment of the firm.

In adopting these recommendations in your company, the guiding principle should be: are your communications with the market helping you attract and retain the right type of investor to support your strategy? Short-term investors that speculate on volatility and short-term performance are unlikely to support abandoning earnings guidance. But they are also not likely to support your efforts to increase the sustained profitability of your organization by focusing on initiatives like engaging your workforce and satisfying customers – which both require time and patience to accomplish.

To build a sustainable business that will succeed in the long-term you must seek backing from market participants who are aligned with this vision. It is time that you revisit whether your communication strategy is the right one in achieving this alignment.

Let’s Be Honest About Lying

If lying — or even just exaggerating a bit — would help your team win, would you do it? More provocatively: should you do it?

Consider the case study unfolding right now in Brazil at the World Cup. For many players, pretending they’ve been fouled is no big deal. Called “flopping” or “diving,” a player who has felt a minimal amount of contact will grimace in agony, fall to the ground, and, often enough, get a bit of sympathy from the referee, who will award his team possession of the ball. But the players on the U.S. and the U.K. teams, reports the New York Times, don’t like to fake fouls. Are they leaving goals — and wins — on the table?

Being honest and never dissembling is very consistent with the bland axioms of a “feel good” leadership discourse, but as in the case of sports, it is also remarkably inconsistent with what actually goes on in the real world. Truth is, some of the most successful and iconic leaders, including many CEOs, were (and are) consummate, accomplished prevaricators.

There’s Steve Jobs, 2005 Stanford commencement speaker and technology icon. The phrase “reality distortion field,” coined by the one of members of the original Macintosh team, refers to Jobs’s amazing ability to present what he would like to be true as if it were already reality.

There’s Larry Ellison, one of the richest men in the world and Oracle CEO and co-founder. Not only did Ellison and Oracle get into trouble in the early 1990s from misrepresenting the company’s actual sales in financial filings. As nicely described in David Kaplan’s book about the origins of the Silicon Valley, Ellison was great at telling customers that a product was available even if he was just thinking about designing it – possibly in response to the potential customer’s inquiry.

In a darker vein, there are the tobacco industry executives, testifying under oath in front of Congress that they had no idea cigarettes had adverse health effects. The CEOs of Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, among others, claiming their balance sheets were in great shape days before both firms collapsed. Former Senator Jon Kyle of Arizona maintaining, in 2011 as the federal government hurtled toward shut-down, that he could not support a continuing resolution that provided funding for Planned Parenthood because more than 90% of Planned Parenthood’s funds went to provide abortion services (the real number is more like three percent). Kyle’s statement, his office later claimed, was never intended to be factual – something that provided fodder for Jon Stewart’s Daily Show.

My takeaways? First of all, the amount of hypocrisy, in the world but particularly in the writing and speaking about leadership, is almost too vast to comprehend.

Second, all the moral “cluck-clucking” about how harmful this dishonesty is does nothing — or maybe even less than nothing — to change anything. Because people mistakenly believe that expressing disapproval is sufficient, they fail to follow through with initiatives that might actually compel people to be (more) honest.

Third, organizations — whether they are companies or soccer teams – exist in ecosystems and if you want to change individual behavior, you need to change the systems in which that behavior occurs. Or as a software company chairman once put it to me in conversation, “if everyone else is misrepresenting product availability, can we afford not to?” (This is where vaporware emanates from.)

Fourth, even as people express outrage over deception and misrepresentation, research shows that many, many people frequently engage in two processes that permit them to continue to do business with and support companies and leaders who have engaged in moral transgressions. One psychological process is moral rationalization — convincing themselves that the misbehavior wasn’t actually that serious. The other process is moral decoupling – arguing that the particular transgression is not relevant to the decision at hand — for instance, that sexual misbehavior is not probative of an athlete’s skills on the field.

Lying is incredibly common in everyday life in part because it helps to smooth over relationships. And the ability to convince people of something even if it is not quite the case, the art of salesmanship, is a quality actually both common to and useful in leaders. Note that even one of the early, iconic stories of truthfulness, George Washington admitting to his father than he cut down the cherry tree, is itself made up.

Strategy Isn’t What You Say, It’s What You Do

You sometimes hear managers complain that their organization has no strategy. This isn’t true. Every organization has a strategy: its strategy is what it does. Think about it. Every organization competes in a particular place, in a particular way, and with a set of capabilities and management systems — all of which are the result of choices that people in the organization have made and are making every day.

When managers complain that their company’s strategy is ineffectual or non-existent, it’s often because they haven’t quite realized that their strategy is what they’re doing rather than what their bosses are saying. In nine cases out of ten, the company will have an ambitious “strategy statement” or mission of some kind: “We are going to be the best in the world in our industry and always lead innovation to the benefit of all of our customers.”

The bosses will have worked hard to come up with such a statement and it may very well be a praiseworthy one. But unless it is reflected in the actions of an organization, it is not the organization’s strategy. A company’s strategy is what the company’s people are actually doing, not the slogan their bosses intone.

The point is that everyone needs to connect the dots. If strategy is what people do rather than what bosses say, it is absolutely critical that each person in the organization knows what it means to take actions that are consistent with the intent of the strategy as asserted.

Strategic choice-making cascades down the entire organization, from top to bottom. This means that every person in the company has a key role to play in making strategy. Performing that role well means thinking hard about four things:

1) What is the strategic intent of the leaders of the level above mine?

2) What are the key choices that I make in my jurisdiction?

3) With what strategic logic can I align those choices with those above me?

4) How can I communicate the logic of my strategy choices to those who report to me?

If you as a manager can do the first three of these four, then you will own your choices and own your strategy. If you do the fourth, you will set up your subordinates to repeat these four things and thereby own their choices and their strategy, and pass on the task to the next layer of the company. If each successive layer assumes this level of ownership, the organization can make its bosses’ statement a real strategy rather than an empty slogan.

And your bosses’ job? It’s to make sure to start the ball rolling by communicating their strategy choices well. Unless they do so, it won’t matter a whit how good their choices appear to be. They won’t be reflected in what you end up doing.

Two Kinds of People You Should Never Negotiate With

The first thing negotiation experts teach is to “separate the people from the problem.” The vast majority of the time, this is sound advice. But as a psychologist, I know that approximately 1% of the time, people are the problem. And in such cases, normal negotiation strategies just don’t work. Here’s how to recognize that rare situation and what to do about it.

First, determine what sort of person or people you’re trying to negotiate with (i.e. your counterparty).

Here are two types of counterparties you should negotiate with, even when it seems difficult.

1. Emotional counterparties. Emotion in and of itself shouldn’t preclude you from reaching a successful agreement – it’s natural for people to feel strong emotion in a conflict situation. Once the conflict is identified and addressed, and parties are allowed to vent, emotion usually dissipates. Keep in mind that some people (and cultures) simply express more feelings than others. Also, some negotiators use emotion strategically to influence the other party. Recognize the emotion, but don’t let it stop you from negotiating.

2. Unreasonable counterparties. We often think people are being unreasonable when they don’t agree with our logic and evidence. But more often, people who disagree with us are simply seeing different problems, and even different sets of facts, than we are. Even if you think the other party is being unreasonable, it’s still possible to bridge the gap and close a deal.

But here are two types of counterparties you should never negotiate with:

1. A counterparty who alternates between conciliation and provocation. People are usually more provocative, or difficult to deal with, at the outset of a negotiation. Then they become more conciliatory as the outlines of a settlement develop. Beware the person who is conciliatory at first, then becomes provocative — and then when you’re about to walk away becomes conciliatory again, and then provocative again. This behavior suggests that he will never be satisfied, nor finished, with the negotiation. What he wants is not a negotiated settlement, but control — over the process and over you. The time and energy it will take to continue will eventually outweigh any potential gains you could achieve through negotiation.

2. A counterparty who persists in seeing people in terms of absolute good and evil. Negotiation is a method for resolving conflicts of interest, not for adjudicating who is at fault. Most people, once they understand this, are willing to exchange concessions in order to satisfy their underlying interests. Watch out for someone who describes people as absolutely good and blameless, or as absolutely evil and responsible. This behavior suggests that he or she lacks the mindset necessary for negotiation. What this person wants is for evil people to be held accountable and punished, and because you are in a conflict with her, you may fall into that category. Walking away would deprive her of the opportunity to punish you. Therefore, if you negotiate, you can expect the process to be painful. You can also expect not to receive meaningful concessions, because this type of person does not believe you deserve them.

Even the best negotiators cannot reach a win-win outcome with people like this, as their underlying interests can’t be addressed with a settlement. The best negotiation advice and practice will not help you in these rare situations. Instead, here are four steps you should take:

Be realistic. This person is not going to change. There is no negotiation strategy you can use to make him or her change. Your goal should be to extricate yourself with the most gains (or least losses) possible. Let’s say you have a tenant behind on the rent. It’s worth negotiating with an emotional, even unreasonable tenant. Deep down, her primary interest is to keep the apartment. She can ultimately be trusted to act in her own interest. On the other hand, it’s not worth negotiating with an alternatively conciliatory, then provocative tenant who blames his neighbors and the property manager for his situation. Deep down, his primary interest is not the apartment; it’s his need to control the people around him.

Stop making concessions. The purpose of concessions is to reach an agreement, but since you’ll never do that (no matter how much you’re willing to give up!), don’t waste your time. That doesn’t mean you won’t incur significant losses. Your goal should be to minimize those losses. For example, if someone on your team fits the description of a no-win negotiator, you may already have made many concessions and picked up her share of the work, while she has yet to follow through on her promises to you. Enough! Do whatever is necessary to get the project finished, but stop making offers to her.

Reduce your interdependence. Take whatever steps you can to reduce your interdependence with this person. You don’t want to depend on him for anything, or owe him anything, going forward. This means, for example, that a lump sum payment for services is better than a payment plan. Working independently on separate pieces of a project is better than working together on the whole thing. If you must continue to work with this person, remember that even very immature children can still play nicely side-by-side if each is given his or her own set of toys.

Make it public, hold them accountable, and use a third party if you can. Avoid private discussions, if possible. Get everything out in the open and put everything in writing. Try to bump accountability to the next level, so someone higher up has to take action if the other party does not follow through on his or her obligations. If you can utilize a third party, like a mediator, arbitrator, or judge, then do so.

Remember, 99 times out of 100, your counterpart has rational underlying interests that you will eventually discover with patience and the right strategies. The secret to negotiating, after all, is to find out what the other party wants and how much it’s worth to him. In those rare cases when your counterparty wants to use the negotiation to control or punish you, however, it doesn’t matter how much it’s worth to him. It’s worth more to you to be free of him and able to get on with your business. Isn’t it?

Focus On: Negotiating

Negotiating Is Not the Same as Haggling

Negotiate from the Inside Out

To Negotiate Effectively, First Shake Hands

The Simplest Way to Build Trust

U.S. Government’s Pipeline of Young Workers Is Drying Up

A reputation for bureaucracy and hierarchy is helping to discourage young Americans from taking government jobs; in a poll of undergraduates, just 2.4% of engineering students and less than 1% of business students listed only government agencies as their ideal employers, according to the Wall Street Journal. Just 7% of the federal workforce was younger than 30 in 2013, compared with more than 20% in 1975, leaving the government without a pipeline of young workers in an increasingly digital age.

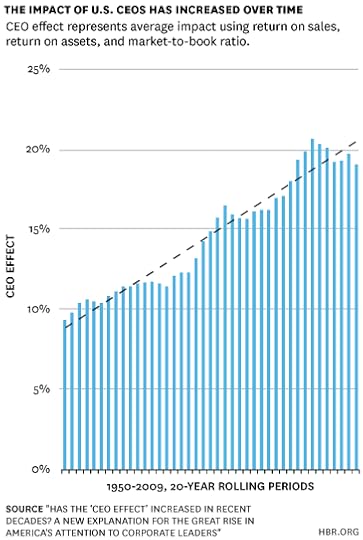

CEO Pay Is Rising, But So Is CEO Impact

It’s no secret that executive compensation has risen much faster in recent decades than wages, particularly in the years since the Great Recession. But a new report from the Economic Policy Institute points to another trend: CEO pay is rising even relative to compensation for the top 0.1% of U.S. earners.

Throughout the 1980’s and early 90’s, CEO pay was roughly three times as high as that of the top 0.1% of earners overall. That ratio spiked in the dotcom years, as CEO pay rose even faster than the stock market. But post-bubble, CEO pay seems to have settled into a “new normal” of 4.5 to 5 times that of top earners. In other words, CEO compensation has risen faster even than other “superstar” earners, a group composed mostly of lawyers, doctors, financiers, and other C-level executives.

The report suggests that, “The large discrepancy between the pay of CEOs and other very high wage earners also casts doubt on the claim that CEOs are being paid these extraordinary amounts because of their special skills.” That may be. The data does suggest that rising CEO pay can’t simply be explained by the broader increase in returns to highly skilled labor.

There’s no understanding CEO pay without noting the dramatic increase in stock options as a share of executive compensation; less clear is whether this explains the change relative to other top earners, or whether they are likewise are increasingly paid in stock. (The numbers from EPI include wages and realized income from stock options at the time they were exercised, but do not include unrealized stock options or other investment income; this may affect the numbers for financiers especially.)

But another explanation is that the value of good CEOs appears to have increased over time, according to recent research.

Less is known about why CEOs seem to matter more — it’s even possible markets just mistakenly think they do. But in any case, the impact of CEOs on companies’ performance has never been higher.

A final point of interest from the report concerns the distribution of pay between the top-paid CEOs and the rest. Contrary to all the talk of “superstar” effects and a winner-take-all labor market, between 2012 and 2013 it was the least-well-paid CEOs who saw the greatest increase in compensation.

Rightly or wrongly, shareholders believe that CEOs matter more than ever, and they’re willing to pay their top executive accordingly.

June 17, 2014

Don’t Do What You Love; Do What You Do

Last April, just two weeks or so before I graduated from Harvard College, I decided I would get a PhD in English (my dissertation might be something about Faulkner and medieval notions of genre). Or perhaps I would get an MFA in creative writing. Just two weeks after I had my diploma in hand, I decided it would be a better idea for me to become an acupuncturist.

Now, almost one year later, I haven’t made any progress with graduate school applications or with my acupuncture career. Instead, I’ve become, somewhat suddenly, a freelance writer who works for a diverse set of companies and organizations, spanning a foundation investing in new digital initiatives for change, a juice cleanse company based in Shanghai, and Cosmopolitan magazine – among others.

To my chagrin, I feel almost like a parodic example of what Forbes has called “Millennial multicareerism.” According to a 2011 survey by DeVry University and Harris Interactive, nearly three-quarters of Millennials expect to work for more than three employers during their careers. I’ve already exceeded three employers in less than one year spent in the workforce. My situation corroborates most – if not all – of the data found in MTV’s recent “No Collar Workers” study: 89% of Millennials reported the need to be “constantly learning” while on the job. Check. 93% of Millennials indicated their desire for a job where they can be themselves. Considering that I can produce good writing from the comfort of my bedroom, I’d say I am definitely myself – perhaps too much myself – “on the job.” Check again. Not only do I work from (my parents’) home, but I also create my own schedule. (Side note: over one-third of Millennials depend on their parents or other family members for financial assistance, according to a Pew Research Survey. Check once more).

And like many, I wonder if I am “following my passion.” Doing “what I love.” I do love writing — but I’m not necessarily passionate about describing the benefits of adding chia seeds to green juice. But after my yearlong search of trying to find that one thing that I was emotionally and intellectually invested in – be it poetry or treating liver stagnation with ancient Chinese principles – I realized that there might be something valuable in letting go of the assumption that “my career” and my passions would be one and the same.

My passions can go on existing fully, growing and changing – and I can “do” whatever it is I do to pay the bills with attention and care, learning new skills and things about myself regardless of whether or not it fills me passion and pleasure. So roughly one year after my college graduation, I stumbled upon a satisfying mantra for my work-life: Do What You Do. It’s an approach based in mindfulness rather than passion.

Miya Tokumitsu has Do What You Love (DWYL), the “unofficial work mantra of our time,” as elitist and untenable, “a worldview that disguises its elitism as noble self-betterment” and “distracts us from the working conditions of others while validating our own choices.” Tokumitsu’s overarching argument is, well, relatively inarguable: the idea that we should all embrace the notion of DWYL makes the false assumption that getting a “lovable” job is always a matter of choice. (The DWYL framework ignores those who work low-skill, low-wage jobs – housekeepers, migrant workers, janitors. These individuals are not simply failing to acquire gratifying work that they “love.”) The idea of DWYL, as Tokumitsu points out, privileges the privileged, those who are in the socioeconomic position to perpetuate this “mantra” as a way to rationalize their professional success and most likely, also their workaholism.

To explore these ideas further I talked with Sharon Salzberg, author of a new book entitled Real Happiness at Work, in which she describes a myriad set of actionable ways to find “real happiness at work” – even at “jobs we don’t like.” By practicing techniques of concentration, mindfulness, and compassion, Salzberg argues that that work is “a place where we can learn and grow and come to be much happier.” When we practice the art of mindfulness, we can tap into what is an opportunity for learning and growth on the job. “We can be purposefully helpful and attentive in conventionally trivial jobs,” says Salzberg, but warns we can also be “blasé ineffectual in potentially world-changing positions.” Or, as my colleague Joanne Heyman put it, “Do one thing at a time. When you are writing, turn off your phone. Really.” This is simple but essential advice that taps into the art of mindfulness.

Sure, some of us are lucky enough to have an idea of what we love to do – and then find an opportunity to get paid to do what it is that we love on the job. But instead of trying to find complete congruence between our passions and our livelihoods, it is perhaps more productive simply to believe in the possibility of finding opportunities for growth and satisfaction at work, even in the midst of difficulties – a controlling boss, demanding clients, competition with your colleagues, insufficient boundaries between your work life and personal life. Recognizing difficulties, and choosing to learn and to grow from them, does not negate their existence or potency, but establishes them as of a distinct facet of one’s life.

So try out the mantra “Do What You Do” (DWYD) – and maybe love will emerge from different places, professional or personal, at different times.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers