Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1409

June 13, 2014

The Rise of the Hands-On Dad

If you’re a dad who works, this is a good time to celebrate. Not only because it’s Fathers’ Day, but because caring about fathers and their needs is no longer a touchy-feely, Phil Donahue kind of thing. Businesses, researchers, the media, and all manner of celebrities have been throwing the spotlight on men who enjoy full lives honoring the importance of both work and family.

Let’s start with the pioneering companies now offering generous paid parental leave to new dads — firms such as Yahoo (8 weeks), PwC (12-14 weeks), and Bank of America (12 weeks). Deloitte and other leading companies support dads with informational resources and parenting groups. And many other companies are paying much more attention to men’s issues in their diversity and work-life programs, even if they haven’t yet fully articulated robust policies for dads. These companies are not addressing working dads’ concerns because they want to be charitable. They understand that a balanced approach to employee management and workplace flexibility are important ways to attract and retain key talent while avoiding the performance declines associated with chronic overwork.

In the world of sports, things might have looked bad a couple of months ago. That was when sports radio personalities Boomer Esiason and Mike Francesa harshly criticized NY Mets player Daniel Murphy for missing the first two games of the 2014 season, because he was on paternity leave. But the outcry that followed showed that their opinions were no longer the norm. As the story made it to national newscasts, Twitter lit up with reactions – over 95% of them rallying behind Murphy and his family. Elsewhere in sports, pro golfer Hunter Mahan left a $1 million tournament he was leading when his wife went into early labor. Over a hundred Major League Baseball players make use of MLB’s paternity leave policy, which was instituted in 2011. Several football players publicly declared they’d miss games to be at the birth of their children.

Meanwhile, some manly celebrity dads, such as Brad Pitt, Mark Wahlberg (cover of the current “fatherhood” issue of Esquire), and Prince William (who took paternity leave from the Royal Air Force when his son was born), are redefining what it means to be a model dad—achieving career success while being highly involved at home. Their public statements and actions are helping change society’s image of what it means to be a “real man.” Goodbye strong silent type; hello modern dad, equally comfortable carrying briefcase, gym bag, or diaper tote.

The entertainment industry is following suit. In 2012, NBC ran the sitcom “Guys with Kids” and last summer A&E premiered “Modern Dads,” both having fun with the new reality of men as primary caregivers for their families. Traditional sitcoms and dramas now highlight far more realistic depictions of modern working dads who are both successful in their careers and highly involved as parents. Phil Dunphy of “Modern Family” is a great example.

Back in the real world – or almost, anyway – the scholarly community is digging into daddy issues. Researchers at Boston College, the UC Hastings School of Law, Wharton and other major universities have led the way by examining the unique challenges faced by working fathers. A solid 20 percent of the program at the upcoming Work and Family Researchers Network conference is specifically focused on working fathers. Three recent (and really good) academic books: Superdads by sociologist Gayle Kaufman; Baby Bust by Wharton’s Stew Friedman; and The Daddy Shift by Jeremy Adam Smith. (And by journalists, Do Fathers Matter? by Paul Raeburn and, forthcoming, Stretch Out by Josh Levs, a response to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In.)

All the evidence that fathers need balance is finding its way to policymakers’ ears. Three US states—California, Rhode Island, and New Jersey—now provide for paid parental leave for both men and women. The FAMILY Act, which has been proposed in the U.S. Senate, would apply this model nationwide. The White House is hosting a Working Families Summit this month to bring together public policy advocate and industry experts to recommend Federal action for working families, and this week hosted a full-day Working Fathers event (where I am proud to have been a panelist).

The news media are picking up on the zeitgeist, and in turn raising awareness of fatherhood issues. For instance, the Today Show, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Esquire, and The Atlantic all extensively and repeatedly covered fathers’ work-family concerns. Glassdoor.com, Forbes, and Fortune routinely laud and highlight companies with progressive work-life programs. In the past few months in my own role as a fathers’ work-family advocate, I have published pieces with Time, The Wall Street Journal, Huffington Post, and The Good Men Project, as well as Harvard Business Review – and been invited to talk about working dads’ issues on MSNBC, NPR, and CBS This Morning.

In fact, there is so much media attention being paid to working dads who are striving for both professional success and parental involvement that The Guardian’s Alex Bilmes recently wrote an article complaining that that modern society is placing too much pressure on him, a traditional low-involvement dad, to be more hands-on. You know an issue has reached a tipping point when the old guard starts a backlash.

Does this all mean we can declare victory? (Or as the kids would say: Are we there yet?) No, there’s still a long way to go. The change has been slow up to now, as social change so often is. But I have the sense that this increased attention on working fathers will only pick up speed. So this weekend, along with any handmade cards or well-intentioned car washes that might come your way, take time to enjoy the good news that it’s more possible than ever before to have a great career, and be a great dad.

Start-Ups Need a Minimum Viable Brand

Sometimes it seems like Steve Jobs’ notorious reality distortion field has extended to all of Silicon Valley. Some eager entrepreneurs think their new product is so brilliant and so unlike anything else out there, that they just need to make it available and people will start clamoring over it. Other start-ups develop a core technology that has myriad possible uses and they’re not quite sure which will be most appealing, so they plan to just put it out on the market and let customers decide.

Approaches like these overlook the importance of brand strategy as the foundation for a successful launch. Having a brand strategy in place ensures that your internal team is aligned around the same goals, and helps determine how you plan to differentiate your product and win loyal customers. Real artists may indeed ship, as Jobs famously exhorted his team, but savvy businesspeople don’t do so without at least a basic brand strategy in place.

It may be tempting to skip brand development in the rush to get a new product to market. Most entrepreneurs are as short on cash as they are on time and they don’t think they can afford to spend either to attend to brand-building. And some people mistake product strategy for brand strategy, without realizing that a compelling brand is comprised of so much more than a product idea.

Since launches should be grounded in a brand foundation while at the same time being pursued with agility and speed, today’s entrepreneurs require an alternative to a complete, robust brand platform. Tech start-ups employ the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) concept, made popular by Eric Ries in The Lean Start-Up, to test product hypotheses with minimal resources. Using a Minimum Viable Brand (MVB) concept can ensure those hypotheses are grounded in strategic intent and market insights.

A MVB is comprised of the core elements of a brand that are necessary to ensure internal focus and alignment as well as external relevance and differentiation. A framework for defining and developing a MVB is the “6 What’s”:

what we stand for – our brand essence

what we believe in – our defining values

what people we seek to engage – our target audience(s)

what distinguishes us – our key differentiators

what we offer – our overarching experience

what we say and show – our logo, look, and lines (messaging)

These six elements cover the basic tenets that should be clearly articulated and commonly understood within an organization prior to it finalizing and launching a new product – and they leave out a fuller dimensionalization of the brand which isn’t necessary at first. Usually the MVB should be established through a couple of focused work sessions among the company leaders and perhaps a creative resource and an external facilitator to provide an objective perspective.

Several principles should inform the development of the MVB elements:

First, every organization should be brand-led and market-informed. Contrary to popular opinion, customers don’t own brands; companies do. Of course customer perceptions of a brand determine the strength and value of a brand, so brand managers must carefully cultivate the proper perceptions. But it would be a mistake to leave it to customers to determine the defining attributes and values that comprise the brand.

As the developer of a new product or solution, a business leader must have a point of view about what their brand stands for and the value they’re offering. This point of view should guide everything the organization does. If they don’t have it figured out, it’s unlikely customers will. A brand strategy may start only as a hypothesis that gets validated – or not – by market reaction, but it should be clearly defined before the product is introduced. That’s what “brand-led” means. “Market-informed” means that the founder’s point of view should be informed by market understanding. Customer insights, competitive dynamics, and broader contextual factors like socioeconomic trends should shape the brand strategy, but not drive it.

The MVB should be guided by the principle that focus is essential for new product viability. A brand should be positioned in a specific way to a specific target customer. Some entrepreneurs may fear that focusing their brand appeal will alienate potential customers – especially when market demand is unclear. But the exact opposite is true. When brands embrace and embody a clear identity and unique positioning, they attract people who are most likely to be loyal, high-quality customers. Think Red Bull, with its buzz-building marketing campaigns, and Harley-Davidson, with its loyal customer base. Actively segmenting the market and seeking out a particular target not only helps with resource allocation, but also cuts through all the noise out there and sends a powerful signal to those customers. After an initial launch, it may be necessary to refine the brand focus and rethink customer targeting, but being open ended from the start is a surefire way for a new product to end up meaning nothing and appealing to no one.

Finally the MVB should be grounded in emotional appeal. There are very few, if any, truly new-to-the-world ideas anymore, which means new products are usually based on nuance or detail, e.g., a new feature or functionality. The problem is, customers rarely notice details and even more rarely value them as much as their creators think they will or should. Of course, novelty usually generates some appeal in the short-term, but decreasing customer attention spans and aggressive competitive imitation makes it difficult to sustain appeal of a new product detail over time. To be perceived as truly distinctive, a brand must convey more compelling, sustaining differentiation and the best way to do so is through emotion. Tying product details to emotional values and seeking emotional connections with customers cultivates more meaningful, sustained customer relationships. (Apple does a great job of this, as the following ad conveys:

The approach to developing and launching a new product is certainly different in today’s information-rich, technology-fueled, and time-constrained business environment. Start-ups now create, evaluate, and refine their offerings iteratively, often expecting to have to reset or pivot as mistakes are made and information is gleaned. But being agile and responsive doesn’t require a ready-fire-aim approach when it comes to brand strategy. An MVB provides the right balance of structure and flexibility.

How the Software Industry Redefines Product Management

Quick, name a product that was developed without using software. It’s difficult, if not impossible. Software has become a crucial part of almost all goods and services. It’s used to design and develop just about any product you can think of, from consumer goods to industrial equipment – or any service or experience ranging from retail customer service interactions to luxury hotel stays. Likewise it’s central to buying most anything these days, and is a growing part of the customer and business experience generally.

But have you thought about the implications of this trend for management practices? The rapid pace of change in software (e.g., new product releases every day, not every year), has caused an increasing pressure on product development in other areas, and on management in general, to change more continuously as well. Indeed, software is emerging as the proving ground for the future of management practices, the way auto manufacturing used to be the proving ground for new management practices (think of the Toyota Production System).

For an example, I spoke with Andy Singleton, CEO of Assembla, a firm that helps software development teams build software faster. He told me the story of Staples vs. Amazon. As you might expect, Staples has a big web application for online ordering. Multi-function teams build software enhancements that are rolled up into “releases” which are deployed every six weeks. The developers then pass the releases to the operations group, where the software is tested for three weeks to make sure the complete system is stable, for a total cycle of nine weeks. This approach would be considered by most IT experts as “best practice.”

But Amazon has a completely different architecture and management process, which Singleton calls a “matrix of services.” Amazon has divided their big online ordering application into thousands of smaller “services.” For example, one service might display a web page, or get information about a product. A service development team maintains a small number of services, and releases changes as they become ready. Amazon will release a change about once every 11 seconds, adding up to about 8,000 changes per day. In the time it takes Staples to make one new release, Amazon has made 300,000 changes. This represents a truly disruptive management and operating model. Just as Southwest Airlines, for instance, has a low cost, point-to-point operating model that disrupted its hub-and-spoke competitors, Amazon has a radically different and better operating model that will crush any competitors who are making one change in nine weeks, while it is making changes every eleven seconds.

Amazon’s approach of continuous product changes opens new possibilities for sensing and responding to the market. Singleton told me that in his industry, they call this “data-driven product management.” He explains, “Product management is transitioning from a process that involves setting strategy and forecasting response, to a much simpler process where we can experiment and directly measure the response of customers to product changes.” In traditional product management, smart people (marketing, engineering, strategy, product managers, R&D) come up with new products and lob them over the wall to operations to put into production. The functional silos and serial process breed miscommunication, slowness, and make it hard to fix problems. Continuous delivery of new software enables experimentation and direct measurement of the response of customers to product changes, creating integrated teamwork, speed, closeness to customers, and facilitating quick fixing of problems in real time.

But the implications of this approach clearly go beyond the process changes for product management (what Singleton calls “Continuous Agile”). The approach naturally entails a faster management system that will increasingly disrupt traditional management systems based on hierarchies and command-and-control, which are inherently internally focused and slow. As Singleton told me, “The technology world is a cult of innovation. We see that innovation drives success in business, and in the larger economy. Software is an almost-pure form of innovation. We call it ‘soft’ because we can change it and reshape it easily.”

The software management practice of continuously releasing new product changes is opening up revolutionary new possibilities for management generally, pointing to a future in which organizations in almost any industry can deliver a steady stream of breakthrough innovations.

A Crisis Doesn’t Bring Colleagues Together

A crisis occurs; layoffs ensue. Colleagues are gone. The rest must adapt. But how? Does the shared crisis bring people closer together? Sadly no, new research by Pedro Neves of the New University of Lisbon suggests. Rather, supervisors vent their frustrations by bullying the most vulnerable of the employees in their charge. Data from employee surveys at 12 large to medium-sized Portuguese companies in industries ranging from financial services to construction showed a clear pattern: Individuals with lower self-confidence and fewer coworker allies received more abuse (as indicated by their agreement with assertions like "My supervisor blames me to save himself/herself embarrassment" and "My supervisor tells me my thoughts or feelings are stupid").

What to do? Apart from recommending that organizations hold supervisors more accountable, Neves suggests that the vulnerable take steps to protect themselves by making friends — since it’s the expectation that no one will come to their aid that makes them targets. —Andrea Ovans

Forgetting Is a Virtue The Case for an Absent-Minded InternetThe Boston Globe

The human brain is fantastic at forgetting. As The Globe's Leon Neyfakh writes, "scientists have definitively shown that forgetting unnecessary information is a crucial component of learning." What if the internet worked the same way? Neyfakh explores emerging thinking around the idea that, as one researcher put it, "forgetting should be more integrated into digital systems." There are several strong arguments and methods for this. One of the first is from Viktor Mayer-Schonberger, who in 2009 argued that we will eventually live in fear of being judged on everything we've ever done or said. Meg Ambrose, an assistant professor at Georgetown, argues that the courts should handle requests that information be taken down. Intel's David Hoffman proposes a regulatory body for such things. Martin Dodge, a University of Manchester lecturer, says computer memory should be designed to be patchy and gradually lose information. And, finally, researchers in Germany have created ForgetIT, software that looks for "unimportant content" to set aside, condense, or delete — what they call "managed forgetting," in which the software learns what a user deems important.

So Many Layers of Meaning Adding Female Characters to New 'Assassin's Creed' Would 'Double the Work,' says UbisoftThe Verge

Video game companies are no strangers to complaints about a lack of female characters. But the explanation Ubisoft gives in this case is particularly troubling: "Technical director James Therien said female assassins were on the company's feature list until 'not too long ago,' but were cut as a matter of 'focus and production.'" Because the game focuses on a male character, Arno Dorian, he became the "common denominator" when it came to design. "It's not like we could cut our main character," says creative director Alex Amancio, "so the only logical option, the only option we had, was to cut the female avatar." It is, in many ways, a very relevant way of talking about gender at work. No doubt, those creating the game were probably under the gun. But it's worth remembering that what seems at the time like a good management decision can say a lot about how your company views the world and who is at the center of it.

There's an App for That Sore ThroatDoes Oscar Sound Cooler Than Aetna? New York Magazine

When health care start-up cofounder Joshua Kushner had a sore throat, he didn't call a doctor. Instead, using an iPhone app, he sent a request to his doctor, who called back within 15 minutes and asked him to check to see whether there were white spots on the back of his throat. There were, and the doctor prescribed Amoxicillin. Behold Oscar, the digital-first health insurance company that has 16,000 subscribers and an estimated year-end revenue of $72 million. It features membership cards that arrive in an iPhone-like box, a medical information "Facebook," health provider rankings, and penetrable bill information. It is, as writer Matthew Shaer notes, "a harbinger of health care as it is likely to exist in the era of Obamacare: aggressively marketed, conspicuously consumerist, bristling with 'functionalities' that digital natives understand and appreciate."

Far from wholly celebratory, however, Shaer also explores some of the company's unsettling implications: putting health histories into the cloud, the Silicon Valley ethos of sharing and openness, the possibility that data could be monetized, and the company's cobbled-together foundation.

Step Right Up Tickets for Restaurants Alinea

Eateries can take reservations over the phone, online, or using software like OpenTable. So why would Alinea, a Michelin three-star restaurant in Chicago, turn to an unproven ticketing system called Next? Turns out it was wildly successful — and Nick Kokonas took to his restaurant's blog earlier this month to explain why. One of his big takeaways is that it created a transparent process and built loyalty because most reservation strategies "are predicated on two people lying to each other" about available tables (you know you've been upsold drinks in the bar). The same is true for the online system: How many times have you clicked "make a reservation" only to have a screen pop up that says "there are no tables within 2 hours of your requested time"? With Next, customers see all the tables available from the start, and they can buy tickets based on what's available.

There are many more business lessons in this piece, ranging from pricing best practices and the pluses of creating direct connections between a restaurant and a patron (instead of through third-party software). And Kokonas shares some compelling data, most notably a drastic drop-off in no-shows after Next was implemented.

BONUS BITSDads

Working Dads Need "Me Time" Too (HBR)

Father's Day Cards Are Out of Touch with the Modern Man (Quartz)

The New Dad: Take Your Leave (Boston College Center for Work & Family)

No Innovation Is Immediately Profitable

The meeting was going swimmingly. The team had spent the past two months formulating what it thought was a high-potential disruptive idea. Now it was asking the business unit’s top brass to invest a relatively modest sum to begin to commercialize the concept.

Team members had researched the market thoroughly. They had made a compelling case: The idea addressed an important need that customers cared about. It used a unique asset that gave the company a leg up over competitors. It employed a business model that would make it very difficult for the current market leader to respond. The classic fingerprint of disruptive success.

With five minutes left in the meeting, it was all smiles and nods. The unit’s big chief (let’s call her Carol) loved the concept, and in principle agreed with the recommendation to move forward. “I just need to see one more thing,” she said. “Can we talk about your financial forecasts? You’ve told me it’s a big market, but I’m not sure yet what we get out of this.”

The team members smiled, because they were prepared. They knew — and they knew Carol had been taught — that detailed forecasts for radically new ideas are notoriously unreliable. So they instead turned to their best guess of what the business could look like a few years after launch. They detailed assumptions about the number of customers they could serve, how much they could make per customer, and what it would cost to produce and deliver their idea. Even using what seemed to be conservative assumptions, the team’s long-term projections showed a big, profitable idea. Of course there were many uncertainties behind those projections, but the team had a smart plan to address critical ones rigorously and cost effectively.

Carol began to look impatient. “That all sounds good,” she said. “But can you double-click on the next 12 months? We can’t afford to lose money on this for more than nine months. When do you turn cash-flow positive?”

The team had estimated it would take at least two years of investment before there was any chance of crossing that threshold. They were being careful to stage investment, since they knew their strategy would change based on what they learned early on in the market, so they expected to keep early losses modest. But there simply wasn’t a realistic way to meet Carol’s request.

My six-year-old daughter Holly and I debate the existence of unicorns, and Carol obviously would come down on Holly’s side. After all, she was seeking a disruptive idea that would deliver market magic; flummox incumbents; leverage a core capability; was new, different, and defensible; and produced financial returns immediately. Would that such a creature existed!

It’s not really Carol’s fault. She was running a business unit coming off a turnaround, and she had steep financial targets to hit over the next 12 months. If the momentum continued, she was in line for a promotion within the next 18 months. If momentum stalled, well, she faced a different outcome.

The simple truth is that Carol wasn’t in a position to absorb the early-stage losses that developing a disruptive idea almost always requires. As much as we like to believe in overnight success stories, most start-up businesses fail, and those that don’t typically go through a fair number of twists and turns before they find their way to success.

Every company should dedicate a portion of its innovation portfolio to the creation of new growth through disruptive innovation. But companies need to think carefully about who makes the decisions about managing the investment in those businesses. If the people controlling the purse can’t afford to lose a bit in the short term, then you simply can’t ask them to invest in anything but close-to-the-core opportunities that promise immediate (albeit more modest) returns.

That doesn’t necessarily mean pulling all disruptive work to a skunkworks-like home far away from your current operations, because that approach can deny your new-growth efforts access to unique assets of your company, like its brands, technology, market access, or talent. And certainly scaling the business will likely involve the existing business. But to have any hope of disruptive success, early-stage funding has to come from a budget that allows for a long-term view.

Ideally in this case Carol’s boss would have created a central pool of resources to test out early-stage ideas. Carol should have a say in how those funds are deployed on ideas that her unit will ultimately have to invest in to scale, especially since her staff will be called on to contribute to up-front work. But she shouldn’t have to feel the financial pinch from initial investments in software development, early marketing, and so on.

If Carol’s boss wasn’t willing to take the short-term hit, then frankly the company shouldn’t waste time pursuing disruptive ideas. That choice has long-term repercussions. But it can be very clarifying for staffers who would otherwise just end up frustrated that, as they get closer to toeing the first mile of disruption, their sponsors find ever more creative ways to say no.

David-and-Goliath Partnerships Bring Innovation to Health Care

Every CEO of a large company worries about the small competitor that will come from behind and change everything. Consider Southwest Airlines, which shook up the airline industry with its low-cost, high-customer service approach to air travel. Or that little book retailing site that opened its online door in 1995 and became the world’s largest online retailer.

That’s why leaders of large healthcare companies are looking over their shoulder and thinking, “What is that small startup that is going to shake up our industry? Who is that David to our Goliath?”

Historically, corporate Goliaths have taken one of two approaches to this kind of upstart competition—try to muscle them out of the market or bring them into the fold through acquisition. But increasingly we’re seeing a third option: collaboration. In these novel relationships, the Davids and Goliaths leverage each other’s strengths and perspectives – and everybody wins.

From a pure business perspective, the greatest value in joining forces is that it makes the pie bigger for everyone and creates more value for consumers in the process.

A concrete example comes from within my own company, McKesson, the largest health-care services firm in the US. In 2005, McKesson invested in a David called RelayHealth that was in the connectivity business before connectivity was hot. A year later, we did acquire them — but rather than swallow RelayHealth whole, we wanted to preserve its innovative DNA and disseminate it across our company.

For its part, the RelayHealth clinical business team is fiercely protective of its culture and thinks of itself as a nimble, high-performing, risk-taking group inside the larger organization. There is some tension in this independence, but with thoughtful management, we’ve been able to bring out best in both organizations.

What makes it work for our company? There are two critical elements: 1) buy-in at the senior level of the organization and 2) the willingness to compromise on some processes that are integral to a large company but can kill innovation for a smaller firm. To be sure, we are still working through some of these issues. Our team at RelayHealth would tell you that they have benefited from the financial and customer resources that McKesson brings to the table. At the same time, they have experienced frustration with some of the structure and requirements that a $137 billion firm has to have in place to manage risk and scale. But even as we work through these issues, we continue to collaborate on ways technology can transform healthcare, and our role in that.

In our relationship with RelayHealth and other similar partnerships, we are seeking new ways to innovate – and looking over our shoulder. We’re mindful of an admonition from Rushika Fernandopulle, the CEO of startup Iora Health: “If you don’t disrupt yourself, someone else is going to do it to you.”

Iora’s own partnership with Dartmouth College offers additional guidance for both the large organization seeking external entrepreneurial ideas and the smaller innovator looking to increase its reach.

Iora Health’s prescription is simple: increase the connection between the patient and their provider. Iora’s reimagined version of primary care brings intense “coach-like” attention to the most costly patients to improve patient health and reduce costs.

The young company recently partnered with Dartmouth to provide primary care to their employees and retirees. As part of the relationship, Iora is collaborating with the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, a traditional healthcare provider that would normally be considered a large and forbidding competitor. But the leadership at Dartmouth-Hitchcock wanted to inject innovation into their primary care program.

Buy-in from the Goliath’s top leadership was critical. From Fernandopulle’s perspective, it takes “pretty progressive leadership” to pull off a successful David-and-Goliath relationship. That buy-in has to come from very senior leadership—middle management typically can’t pull off such an unusual partnership.

Fernandopulle also advises other Davids to be realistic about their expectations for the relationship with a large organization. Sometimes Goliaths are most comfortable with the smaller innovator if the innovator is already partnered with a known entity, as Fernandopulle did when he partnered with Mercer to provide primary care services to Boeing employees.

Finally, Iora’s top doctor advises Davids to put their branding ego aside and let the larger organization get the credit for the successful partnership. The startup’s value will be seen through the results of the partnership—but sometimes the larger organization’s leadership may need to claim more of the credit at the beginning of the project.

There are upsides and downsides for both organizations when large and small come together. But because large organizations may find it difficult to innovate from inside, looking outside the enterprise can help force change, bring fresh perspectives and challenge status quo thinking. At the same time, economic pressures mean companies need to be efficient and operating at scale. Goliaths can bring efficiency and scale to the table for the smaller organizations.

Given the unprecedented level of change gripping the health care industry, large and small health care organizations will need to depend on innovation, creative thinking and sometimes each other to successfully navigate the evolving marketplace.

History Backs Up Tesla’s Patent Sharing

Yesterday, Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, the electric car company, announced that Tesla would make its patents freely available to competitors. To many people this announcement seemed surprising if not shocking. After all, the conventional wisdom holds that patents are essential to keep competitors from imitating innovations, especially for small startup companies. If rivals imitate, they will drive down prices, wiping out the potential profits on innovation, thus making it difficult or impossible to earn a return on R&D investments.

But while this conventional wisdom applies to mature technologies, it is often wrong during the early stages of major new technologies. Indeed, since the Industrial Revolution, innovators have made their inventions and knowledge freely available to rivals during the early stages of critical new technologies including textile technology, Bessemer steel production, the personal computer, wireless communications, and the Open Source software that powers the Internet. Often innovators did not patent their inventions or when they did, they allowed other innovators to use them freely. Nearly two hundred years ago, the Boston Manufacturing Company, the leading producer of cotton cloth using the most important technologies of the Industrial Revolution, stopped enforcing its patents, allowing competitors to use its innovations, much like Tesla.

Moreover, these innovators shared knowledge for sound economic reasons. Some commentators have noted that Tesla’s move will help it hire talented engineers. Others see it as a brilliant PR move. They are right, but Tesla’s action is also central to their business strategy. There are real benefits to sharing knowledge that substantially outweigh the costs and this economic logic is very similar to the economics that motivated past innovators to share.

Consider first the benefits. Musk tells us “We believe that Tesla, other companies making electric cars, and the world would all benefit from a common, rapidly-evolving technology platform.” In order for Tesla to succeed, a lot of complementary knowledge and infrastructure needs to be developed. Auto mechanics need to learn how to repair electric vehicles; drivers need to learn to drive and to maintain them; new marketing and distribution channels need to emerge; and the roads need to be populated with charging stations for long distance travelers. All of these developments will happen faster if multiple electric vehicle makers coordinate around common, open standards, each contributing knowledge as new techniques are tried. The success of electric vehicles will benefit most from powerful “network effects” when they share enough knowledge to create a “common, rapidly-evolving technology platform.”

These benefits were much the same for early stage technologies in the past. A large body of complementary knowledge was needed to implement these technologies. The engineers of the early US Bessemer steel mills met regularly with their rivals as a self-described “band of loving brothers” until they had developed common standards for producing steel, slashing production costs by 78% in the process.

But what about the argument that competition will destroy profits? The critical thing about many major new technologies begin as a competition between two groups: those using the old, dominant technology and the other startups using the new technology. Musk realizes that, “Our true competition is not the small trickle of non-Tesla electric cars being produced, but rather the enormous flood of gasoline cars pouring out of the world’s factories every day.” This is likely to remain true for a decade or two. And as long as it remains true, the prices and profits of Tesla will be determined by the market share of gasoline cars, not by the trickle of rivals with whom Tesla is sharing its inventions. Sharing knowledge with them will not undercut profits in the near term.

This pattern, too, is seen in past examples of knowledge sharing. The early Bessemer steel mills competed mainly against makers of iron rails for the railroads, not against the trickle of other Bessemer mills. The early textile makers competed against home weavers and British imports.

This history explains why the conventional wisdom is sometimes wrong, but it also contains a warning for the future: the conditions that make knowledge sharing advantageous today won’t last forever. Eventually electric vehicles will replace much of the market for gasoline-powered cars. Then competition from other electric vehicle makers will affect Tesla’s profits and such extensive sharing might no longer be beneficial. But that is tomorrow’s problem. Elon Musk is shrewd to grasp today’s opportunity firmly, despite the conventional wisdom.

Why We Fight at Work

Disagreements and debate at work are healthy. Fighting is not. That’s because fighting with one’s boss is just as confusing and destructive as fighting with a powerful family member. Fighting with a colleague feels like fighting with a friend or a sibling. Fighting with people who have more or less power than we do feels like bullying.

Naturally, we have to learn to deal with aggression at work. But first, we need to understand the real sources of conflict—not the textbook “struggle over resources” issues—but the underlying psychological reasons why people fight. Then, we can develop ways to engage in conflict that keep us sane, help others, and hopefully support the organization.

What does conflict at work look like?

Conflict at work comes in several forms. First, there are the people who pretend there’s no problem when there’s an obvious problem. They may say something like: “I don’t see an issue here.” When you try to explain, you’re hit with: “You’re being illogical.” When things escalate, this becomes the ultimate insult: “You’re too emotional.” (Women, beware.) Turning the conflict around so it’s about you is a tactic—a crazy-making tactic. No matter what you do, you’re seen as unreasonable or you’re labeled as the one picking a fight. In this scenario, they win and you lose.

Another common approach to conflict at work is outright aggression. People who habitually choose this approach are bullies. They are the hyper-competitive, anything-goes, take-no-prisoners, narcissists among us. These people prove their worth by dominating. They’re especially dangerous because they often have vicious followers who do their bidding. When these bullies get mad, watch out.

Then there’s my least favorite tactic of all—passive aggressiveness. Passive aggressive people seem to be supportive, logical, and even helpful—until you read between the lines. Their attacks don’t seem like attacks because they are so good at hiding their word-weapons. Sometimes, you don’t even know you’ve been hit until later. Fighting with these people is like shadow boxing.

Why do people fight at work?

Disagreements and even true conflict are inevitable at work, for some pretty good reasons: the constant flood of information means that we are always touching different parts of the elephant and constant change requires constant debate. In a perfect world, we follow the textbook advice, treat these sources of conflict logically, behave like adults, and get on with it.

The problem is, we’re not working in a perfect world, and none of us is perfect. We each bring our own baggage to work each day. And, some of our issues rear their heads again and again. At the top of my list of sources of work conflict are: personal insecurity, the desire for power and control, and habitual victimhood. Let’s take these each in turn.

Insecurity. We are all insecure about something. And when insecurity gets triggered, we can find ourselves behaving in ways that don’t make us proud. We try to hide our mistakes, avoid healthy debate, shy away from disagreements and even lash out unnecessarily, just to protect ourselves. Sometimes we even start fights just to distract people.

Nobody’s perfect. So why spend so much time and energy trying to prove that we are? Wouldn’t it be better to just work with our shortcomings, rather than create complicated work-arounds that confuse people and inevitably cause conflict?

Desire for power. Most people want to feel that they have some control over their lives and actions—at work as well as at home. We want to have impact. We want to help people achieve goals, and we want the recognition we deserve. This is natural and healthy: proactively looking for ways to influence and impact people for the sake of the group is the epitome of good leadership. Unfortunately, many people are at the mercy of this very human need. Instead of working with others, the goal becomes to position ourselves above others. When it’s pathological, shared goals don’t really matter anymore, and shared credit isn’t an option. This stance, however well hidden, puts everyone on high alert and on the defensive. This is because we know that even normal disagreements about things like resources are actually primal struggles about who has power over whom.

Habitual victimhood. Insecurity can be a good thing—it can mean that we are in touch with our shortcomings and that we are ready to learn. And many people use their power well, for the good of the group. Habitual victimhood, however, has no redeeming value whatsoever. Still, it is all too common to find perpetrator-victim pairs in organizations. The script is so predictable: “He does thus-and-so all the time and I can’t do anything about it.” Really? You can’t do anything about being metaphorically kicked to the ground over and over again? Why do people put themselves in this position? It’s deep, for sure, and quite honestly if you find yourself the victim over and over, it wouldn’t hurt to talk with a good therapist. Or at least a good friend. You need to figure out how being a victim serves you. For example, giving up control means that we have a ready-made excuse and can’t be held accountable.

What can you do about conflict at work?

The first thing we can do is to admit that conflict at work is real and pervasive, and just as painful as fights and struggles in other areas of life. Let’s stop pretending that somehow it is more rational, more sterile than conflict elsewhere in our lives.

Second, we need to cultivate real empathy and compassion for others. What drives them? What are they insecure about? How would it feel to be them? This kind of reflection isn’t easy, and it is tempting to let your biases and stereotypes guide your conclusions.

Finally: Our feelings matter, and they need to be attended to first and always, not as an afterthought. So, dealing with conflict at work starts with self-awareness. What are you insecure about? Why? Is it rational, or are those old tapes from childhood still there, playing long after they stopped being true or useful? How do you feel about power—yours and others’? What happens when your freedom is threatened, or when someone tries to control you? And…do you make yourself a victim? Why? How does this serve you? Where else in your life do you do this? Is it really working?

This kind of self-awareness isn’t superficial—it’s deep. And it will help. Not just you, but your colleagues and your organization, too.

Focus On: Conflict

When and How to Let a Conflict Go

Managing Two People Who Hate Each Other

Get Over Your Fear of Conflict

How to Repair a Damaged Professional Relationship

Where Dads Do Moms’ Chores, Daughters Have Unstereotypical Career Hopes

Surveys of families with children aged 7 to 13 show that when fathers take on stereotypically female roles at home, such as child care and cooking, their daughters more easily envision balancing work with family and having careers that are less gender-stereotyped, says a team led by Alyssa Croft of the University of British Columbia. The reasons are unclear; one possible explanation is that counterstereotypical fathers unwittingly model future potential mates, signaling to their daughters that they can expect men to help at home. Also unclear is why boys are unaffected: When fathers enact more-egalitarian gender roles at home, their sons don’t internalize these roles, the researchers say.

Working Dads Need “Me Time” Too

Mother’s Day is widely recognized as a day to acknowledge moms who all-too-often forsake relaxation and self-care for the sake of family, work, and community responsibilities. It’s no surprise that many Mother’s Day gifts are designed to give Mom one day to put herself first (e.g., sleeping in, a break from chores and cooking, getting a massage or pedicure). Yet, as Father’s Day nears, few people acknowledge the fact that dads, too, are now increasingly engaged in childcare and household responsibilities, in addition to demanding jobs.

Fathers are more likely than mothers to log long hours at the office, and they report feeling even higher levels of work-life conflict than mothers do. In addition, fathers who give higher-than-average levels of childcare, ask for paternity leave, or interrupt their careers for family reasons are harassed more at work, receive worse performance evaluations, and get paid less than men who either don’t have kids, or who don’t spend much time with them. And when fathers ask for flex-time, they’re often even more penalized than mothers are for making the same request.

We need to recognize that working fathers, like working mothers, are susceptible to the “putting everyone else first” challenge of modern working-parenthood. We’re already seeing this starting to happen. For instance, this year, for the first time, the White House convened sessions on working dads as part of their Summit on Working Families, TODAY released the findings from their Modern Dad survey about the changing roles of fathers in our society, and Scientific American just published the book Do Fathers Matter?: What the Science is Telling us about the Parent we’ve Overlooked.

This increased visibility will hopefully lead to the systemic interventions we know work best; but in the meantime, how can individual dads start solving the problem of work-life conflict?

We set out to study working fathers of young children in our Total Leadership program – a widely recognized leadership development program that focuses on integrating four areas of life (work, home, community, and self) for improved performance in all four. The process starts with each participant diagnosing what matters most to him and engaging in dialogues with key stakeholders (spouse, boss, kids, and so on). Each participant then experiments with new ways of getting things done that serve all the different parts of their lives; they pursue “four-way wins.” (See this HBR article for descriptions of the nine types of experiments.)

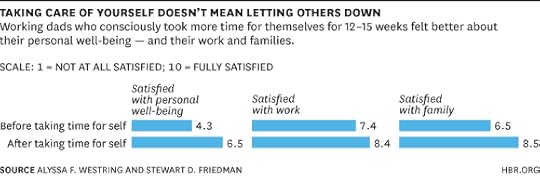

We conducted an in-depth analysis of 36 working fathers of young children (under age three) who participated in this program as part of their Wharton Executive MBA. At the beginning of the program, it was clear that these fathers were skipping sleep, exercise, healthy eating, spiritual growth, and relaxation for the sake of their work and family responsibilities. Indeed, at the start of the experiment, they rated their satisfaction with their personal well-being as an average of 4.3 on a scale from 1 (Not at all Satisfied) to 10 (Fully Satisfied). This is in contrast to their reported satisfaction with work and with family, which were both rated significantly higher, with averages of 7.4 and 6.5, respectively. In other words, they were putting everyone else first – and themselves last.

So it wasn’t surprising that when asked to design experiments to enhance performance in all areas of their lives, the most popular type of experiment for these new dads was “rejuvenating and restoring” (as compared to, say, planning or time-shifting). R&Rs involve taking care of yourself (e.g., changes in diet or physical activity, doing meditation, taking vacation, etc.) to increase capacity and performance at work, in your family, and in the community via positive spillover – indirect effects that ripple out from the self to other parts of life. In an earlier study of the nine kinds of experiments (forthcoming in the Journal of Management Development), 57% of program participants completed an R&R. However, 75% of those in our working fathers sample did so, indicating a greater need for this sort of change in their lives.

After their conversations with key stakeholders and some intensive coaching, the fathers in our sample implemented their experiments over the course of the subsequent twelve to fifteen weeks. One decided to do yoga for three hours each week, with the expectation that it will “improve my physical fitness, mental concentration at work and school, outward confidence, and show importance of exercise to my kids and other stakeholders.” Another committed to “exercise three times regularly a week because this will allow me to have more energy at home for the limited time I have for my wife and kids, providing me with the energy at work to handle stress better, be more patient, and be a much better leader… it will allow me to regain the health and peace of mind I so desperately need for myself.”

The goal is not for participants to implement their experiments perfectly, exactly as designed. Instead, the purpose is to gain experience with trying new ways of doing things and thereby increase one’s confidence and competence in one’s capacity to initiate change that’s truly sustainable. We were not surprised to find that many participants struggled to implement their well-being initiatives exactly as designed, given the intensive demands of their work, school, and family responsibilities.

Yet, even for those who struggled to fully follow through on attending anew to their personal needs as they had mapped out in the designs for their experiments, there was much growth and an increase in optimism. For instance, one father wrote that “this experiment and the introspection I have gained has taught me that without a healthy ‘you’ it is very difficult to excel or be your very best in other areas.” Another wrote, “Giving time to oneself is very important. In our daily lives which have become so wired and busy, we hardly do that. Exercise and diet is just one of the ways to achieve that.” Just as with working moms, several of the dads noted the importance of caring for oneself as a foundation for caring for others. One father aptly wrote, that “I heard someone refer to this as the analogy of putting on the oxygen mask before helping others, and that is how I feel.”

At the conclusion of our program, we asked participants to again rate their satisfaction with the different areas of their lives. Working fathers’ satisfaction with the “self” domain improved from 4.3 to an average of 6.5, a statistically significant increase. And these gains in the personal domain were not accomplished at the cost of reduced satisfaction other domains. Significant increases were also observed, as satisfaction with work and family also rose, to an average of 8.4 and 8.5, respectively. On separate measures, participants also reported significant improvements in physical health and mental health, as well as a reduction in stress.

All of us fall into the trap of saying we can’t afford to take time for ourselves; what’s important about our study is that it shows that on the contrary, we have to take time for ourselves in order to effectively serve others. It isn’t only moms who tend to put themselves at the bottom of the list, nor is it only mothers who can benefit from more self-care. Today’s fathers need it, too. This Father’s Day, let’s acknowledge the changing role of fathers in our society and appreciate that they may need a little encouragement to put themselves first. Instead of buying Dad a new power tool or another necktie, give him something that helps him take care of himself so he can really be there for all the people who depend on him.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers