Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1410

June 12, 2014

Succeeding Quietly in Our Recognition-Obsessed Culture

David Zweig, author of Invisibles, on employees who value good work over self-promotion. For more, read his article, Managing the “Invisibles”.

What Tesla Knows That Other Patent-Holders Don’t

Tesla made a seemingly unusual move today: it invited competitors to use its patents, for free. In a post on the company’s blog, CEO Elon Musk declared that Tesla’s “true competition is not the small trickle of non-Tesla electric cars being produced, but rather the enormous flood of gasoline cars pouring out of the world’s factories every day.”

Rather than worrying about car companies copying their technology, Tesla now hopes they will do so, in order to expand the overall market for electric vehicles.

This counterintuitive strategy is more than good PR — although that too — say several IP experts. In fact, it reflects a keen understanding of both innovation and talent.

The first thing to note is that Tesla is not truly giving away its secret sauce, the source of its competitive advantage. “There’s a lot of thinking in the research these days on the gap between the codified knowledge that is patentable and gets disclosed versus tacit knowledge that really exists in how you actually produce,” says Orly Lobel, a law professor at the University of San Diego specializing in intellectual property. “That gap is probably relevant in this market.”

A Tesla vehicle is quite literally more valuable than the sum of the parts, even when the value of the patented technology is included. “They have this sexy car that people are increasingly liking,” says Lobel. “It’s something different from just the aggregation of the knowledge in the patents.”

That thinking is echoed by Alberto Galasso, another IP expert at the University of Toronto, who put it this way: “A patent on a great technology is worth nothing if there is no threat of imitation.” Access to the patents doesn’t ensure that a competitor can execute on an equally innovative product.

Tesla is trying to thread the needle of expanding the industry without giving up its competitive position. By giving away access to its patents it is offering competitors a leg up, but not fully ceding its lead in innovation.

“Tesla is very much the dominant innovator in the industry, so it can afford making that move,” Lobel told me, adding that the company may hope that it will trigger reciprocal action by others equally committed to furthering the industry.

But there is another advantage to the strategy. The move may also help with recruitment, says Lobel, either directly, by attracting engineers committed to open innovation, or indirectly by boosting the brand.

Tesla will presumably keep patenting for defensive purposes, Lobel suggests. But the basic idea articulated in Musk’s post that “Technology leadership is not defined by patents” holds. As Lobel puts it, “Really, the innovation is in creating the end product really well.”

Why Smart People Struggle with Strategy

Strategy is often seen as something really smart people do — those head-of-the-class folks with top-notch academic credentials. But just because these are the folks attracted to strategy doesn’t mean they will naturally excel at it.

The problem with smart people is that they are used to seeking and finding the right answer; unfortunately, in strategy there is no single right answer to find. Strategy requires making choices about an uncertain future. It is not possible, no matter how much of the ocean you boil, to discover the one right answer. There isn’t one. In fact, even after the fact, there is no way to determine that one’s strategy choice was “right,” because there is no way to judge the relative quality of any path against all the paths not actually chosen. There are no double-blind experiments in strategy.

To be a great strategist, we have to step back from the need to find a right answer and to get accolades for identifying it. The best strategists aren’t intimidated or paralyzed by uncertainty and ambiguity; they are creative enough to imagine possibilities that may or may not actually exist and are willing to try a course of action knowing full well that it will have to be tweaked or even overhauled entirely as events unfold.

The essential qualities for this type of person are flexibility, imagination, and resilience. But there is no evidence that these qualities are correlated with pure intelligence. In fact, the late organizational learning scholar Chris Argyris argued the opposite in his classic HBR article Teaching Smart People How to Learn. In his study of strategy consultants, Argyris found that smart people tend to be more brittle. They need both to feel right and to have that correctness be validated by others. When either or both fail to occur, smart people become defensive and rigidly so.

This does not imply that smart people should be kept away from strategy. It does imply however that strategy should not be a monoculture — as it can become in strategy consulting firms — of high-IQ analytical wizards. Great strategy is aided by diversity of thought and attitude. It needs people who have experienced failure as well as success. It needs people who have a great imagination. It needs people who have built their resilience in the past. And most importantly, it needs people who respect one another for their range of qualities, something that is often going to be most difficult for the proverbial smartest person in the room.

Adding Fees That Consumers Won’t Hate

TicketMaster recently settled a pricing-related class action lawsuit that provides important pricing lessons to all businesses. In addition to paying for admission to an event, the ticketing giant used to tack on additional charges such as convenience, facility, order-processing, and delivery fees to purchases. The class action plaintiffs claimed these fees were misleading; had they known TicketMaster was making profit off the order-processing and delivery fees, the suit claimed, they might not have purchased.

As a pricing consultant who goes to a lot of concerts, I’m particularly interested in this litigation. When I read the lawsuit, my first thought was that it’s crazy. Why is it anyone’s business how a company’s profit is structured? Isn’t it the final price that matters—if you pay $25 to attend an event, does it really matter what individual fees (and the associated profit structure) that cumulatively make up the final price?

But then I thought about a purchase I recently didn’t make. I send engraved thank you cards to friends and business associates as an expression of my gratitude. Recently, I was pleased to see my favorite cards on sale for $19 (for a box of 10) on a leading ecommerce site. Ready to purchase, at checkout a $6 shipping fee popped up. “Six dollars to ship a box of cards?” I noted with a twinge of anger. I felt the e-tailer was taking advantage of me and as a result, I didn’t make the purchase. I later reflected on this experience and concluded that had the price been structured as $25 including shipping, or even $22 plus $3 shipping, I would have purchased. It was simply the $6 shipping fee – not the total price – that bothered me. All of a sudden, $25 wasn’t $25.

Understanding this consumer behavior, StubHub recently moved to an “all-in” pricing strategy. Market research by the eBay-owned ticket reseller revealed their buyers didn’t care for the mandatory additional fees that were tacked on at checkout. Previously, after agreeing to a ticket price, customers were hit with a delivery charge as well as a sketchy 10% “buyer fee.” While a delivery charge is reasonable and customary, this “buyer fee” seemed out of place (or at least could have been phrased better). For example, since StubHub provides excellent fraud insurance (if a resold ticket is fake, one call to StubHub will get you into the event no matter what), this charge would have been more consumer friendly had it been labeled a “buyer security fee.” Now Stubhub includes all fees in the initially viewed price. As a result of moving to this all-in pricing strategy, StubHub claims its customer satisfaction ratings have increased by 10 points and sales are growing.

Since $25 is indeed $25, why do individual component prices matter? To be clear, customers don’t always behave in an economically rational manner. After all, is 99 cents significantly cheaper than one dollar? Most consumers behave as if it is, which is why so many prices for consumer goods are set at a penny below a round dollar value.

The key lesson is that many customers evaluate prices sequentially. Each presented price in a transaction is judged for fairness. Thus, even if the total price is acceptable, a charge that is not customary or seems unusually high puts the entire transaction at risk.

Companies can use this understanding of sequential pricing decision-making to their advantage. To be clear, I don’t recommend including all of the customary charges into the initially presented price – as StubHub now does – for two reasons. First, this “all-in” price will likely be higher than the “first” price (before additional charges) of competitors, which can be disadvantageous. But more importantly, it’s the act of having customers review (and evaluate) these customary charges that is critical to boosting a company’s brand. For instance, if shipping is “free,” we all know that it is baked into the price. However if shipping is presented as a low-priced “pass through” cost to customers, many of us will code this as being fair.

I’m dubious on the merit of class action plaintiffs’ key claim – they might not have purchased had they known TicketMaster was earning profit from ancillary fees. After all, what’s next? Outlawing “free shipping” in favor of “shipping included?” Still, the lawsuit highlights how all companies can benefit from smarter sequential pricing. By strategically setting customary additional charges in a manner that engenders a sense of fairness, companies can enhance their brand.

Are Apple’s Patent Wars a Marketing Strategy?

The latest battle in the three-year long Apple-Samsung patent saga concluded few weeks ago. In contrast to previous litigation between the two tech-giants—which revolved on the overall look of the phones—this case focused around autocomplete, tap-from-search and slide-to-unlock software. Despite the technical nature of these innovations, there are a few broad managerial lessons that have emerged from this prominent patent case.

Often, managers think about patent litigation as a “narrow” strategy to protect a particular technology against a specific infringer. Plenty of management books describe patent litigation in such a narrow way: you file a suit to recover damages from someone who is copying you. The Apple-Samsung battle shows that patent litigation can be a much broader and powerful strategy. In particular, there are two features of the case which are worth pointing out.

The first one is the marketing effect of IP litigation. “Apple says Samsung copied iPhone” was the typical news headline during the first weeks of litigation. The case was not only mentioned on specialized business press; it was front page news material for major newspapers around the globe. International news channels devoted several minutes of their prime time to the patent case. The opening statements by Apple’s lawyer, Harold McElhinny, alleging that “Samsung copied the iPhone” and that “Samsung went far beyond the world of competitive intelligence and crossed into the dark side” were translated in a multitude of languages and displayed next to pictures of Steve Jobs, one of the most charismatic CEOs of all time. How much would it cost to have similar media coverage through a traditional advertising campaign? Probably way more than Apple’s lawyer bills. And this is particularly interesting given the aggressive marketing strategy implemented by Samsung in the past few years. AdvertisingAge reports that in 2012, Samsung increased its U.S. advertising budget more (percentage-wise) than any other high tech company. For the same year, Samsung global ads expenditure was $4.3 billion; that is more than four times the expenditure of Apple. At this point it seems reasonable to add patent litigation to Apple’s history of non-traditional marketing strategies.

A second lesson from the case is that IP litigation with one competitor may strongly affect the patent strategy of other competitors. The most interesting aspect of the Apple-Samsung patent battle is that the actual technology war is not between Apple and Samsung. The real enemy of Apple is Google, whose Android operating system runs on Samsung’s phones. So why has Apple not sued Google? The answer is Google’s business model. Android is an open-source system, and hardware companies do not pay for it. Google profits are generated indirectly from ad revenues derived from Android device use. Instead, Samsung makes a lot of money selling phones that use Android. It is much easier to persuade a jury to force Samsung to give up some of its phone revenue than it is to persuade a jury to convict a company that gives away software for free.

But taking Samsung to court affects Google, too. First, it makes other hardware makers more reluctant to use Android after seeing Apple litigating with Samsung, the leader among Android device makers. Second, it shows Google the value of Apple’s patents. Unsurprisingly, Google and Apple called a truce on their litigation on Google’s Motorola unit patents only a few days after the Apple-Samsung court decision. Firms need to learn the value of each other’s patents to settle disputes, and court decisions are a powerful way to learn.

In a research article recently published in the Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, I study a number of patent litigation cases which took place in the semiconductor industry between 1985 and 2005. I show that very often, a suing and counter-suing pattern, as the one observed in the Apple-Samsung battle, ends with a grand settlement in which firms enter a broad cross-licensing agreement. This is particularly likely for capital intensive firms that invest heavily in manufacturing facilities. The study suggests patent litigation plays a key role in convincing companies of the value of each other’s patent portfolios. It is not uncommon for top managers to overestimate the value of their technologies, and the damages awarded in the Apple-Samsung case confirm such overconfidence (Apple obtained less than 6 percent of the $2.2 billion requested). Court assessments help create more reasonable expectations and facilitate future technology exchange. This perspective can also explain why the settlement agreement between Apple and Google is not as broad as other cross-licensing deals observed in high-tech industries. This is because a broad cross-license agreement between Google and Apple would require much more information than the subset indirectly released from the Apple-Samsung court decision.

The Apple-Samsung patent war illustrates how patent litigation has impacts that go far beyond stopping a specific firm from copying a particular technology. This narrow view overlooks the effect it has on brands, and on other competitors not named in the suits. In considering their own IP strategy and in responding to litigation, managers can benefit from thinking more broadly about patent wars and recognizing their multiple effects.

The Neurochemistry of Positive Conversations

Why do negative comments and conversations stick with us so much longer than positive ones?

A critique from a boss, a disagreement with a colleague, a fight with a friend – the sting from any of these can make you forget a month’s worth of praise or accord. If you’ve been called lazy, careless, or a disappointment, you’re likely to remember and internalize it. It’s somehow easier to forget, or discount, all the times people have said you’re talented or conscientious or that you make them proud.

Chemistry plays a big role in this phenomenon. When we face criticism, rejection or fear, when we feel marginalized or minimized, our bodies produce higher levels of cortisol, a hormone that shuts down the thinking center of our brains and activates conflict aversion and protection behaviors. We become more reactive and sensitive. We often perceive even greater judgment and negativity than actually exists. And these effects can last for 26 hours or more, imprinting the interaction on our memories and magnifying the impact it has on our future behavior. Cortisol functions like a sustained-release tablet – the more we ruminate about our fear, the longer the impact.

Positive comments and conversations produce a chemical reaction too. They spur the production of oxytocin, a feel-good hormone that elevates our ability to communicate, collaborate and trust others by activating networks in our prefrontal cortex. But oxytocin metabolizes more quickly than cortisol, so its effects are less dramatic and long-lasting.

This “chemistry of conversations” is why it’s so critical for all of us –especially managers – to be more mindful about our interactions. Behaviors that increase cortisol levels reduce what I call “Conversational Intelligence” or “C-IQ,” or a person’s ability to connect and think innovatively, empathetically, creatively and strategically with others. Behaviors that spark oxytocin, by contrast, raise C-IQ.

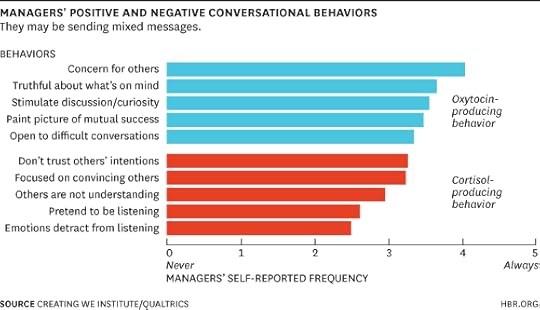

Over the past 30 years, I’ve helped leaders at companies including Boehringer Ingelheim, Clairol, Donna Karen, Exide Technologies, Burberry, and Coach learn to boost performance with better C-IQ. Recently, my consultancy, The CreatingWE Institute, also partnered with Ryan Smith, CEO of Qualtrics, the world’s largest online survey software company, to analyze the frequency of negative (cortisol-producing) versus positive (oxytocin-producing) interactions in today’s workplaces. We asked managers how often they engaged in several behaviors — some positive, and others negative — on a scale of 0 through 5, in which 0 was “never” and 5 was “always.”

The good news is that managers appear to be using positive, oxytocin and C-IQ elevating behaviors more often than negative behaviors. Survey respondents said that they exhibited all five positive behaviors, such as “showing concern for others” more frequently than all five negative ones, such as “pretending to be listening.” However, most respondents – approximately 85% — also admitted to “sometimes” acting in ways that could derail not only specific interactions but also future relationships. And, unfortunately, when leaders exhibit both types of behaviors it creates dissonance or uncertainty in followers’ brains, spurring cortisol production and reducing CI-Q.

Consider Rob, a senior executive from Verizon. He thought of himself as a “best practices” leader who told people what to do, set clear goals, and challenged his team to produce high quality results. But when one of his direct reports had a minor heart attack, and three others asked HR to move to be transferred off his team, he realized there was a problem.

Observing Rob’s conversational patterns for a few weeks, I saw clearly that the negative (cortisol-producing) behaviors easily outweighed the positive (oxytocin-producing) behaviors. Instead of asking questions to stimulate discussion, showing concern for others, and painting a compelling picture of shared success, his tendency was to tell and sell his ideas, entering most discussions with a fixed opinion, determined to convince others he was right. He was not open to others’ influence; he failed to listen to connect.

When I explained this to Rob, and told him about the chemical impact his behavior was having on his employees, he vowed to change, and it worked. A few weeks later, a member of his team even asked me: “What did you give my boss to drink?”

I’m not suggesting that you can’t ever demand results or deliver difficult feedback. But it’s important to do so in a way that is perceived as inclusive and supportive, thereby limiting cortisol production and hopefully stimulating oxytocin instead. Be mindful of the behaviors that open us up, and those that close us down, in our relationships. Harness the chemistry of conversations.

Don’t Offer Employees Big Rewards for Innovation

It stands to reason that if you want your employees to come up with high-powered ideas, you need to offer high-powered rewards. That’s why Google created its Founders Awards to provide stock worth up to several million dollars as an incentive to innovation.

But our research shows that high-powered rewards are no better than low-powered incentives at producing radical innovations. They may generate excitement and high hopes, but they result in few breakthrough concepts.

High-powered incentives do produce a flood of ideas, but that’s not necessarily a good thing—a flood can be overwhelming, leaving companies unable to act on many of the ideas. You’re better off implementing low-powered rewards, which are much cheaper and yield a more manageable stream of ideas.

The basic question that motivated our research—Should firms reward their employees for innovative ideas?—is far from settled, even after years of research. Various management scholars, for instance, have argued that rewards are hard to administer and may corrupt employees’ motivation and creativity. Nevertheless, many firms continue to reward good ideas: 3M and Google allow employees to spend 15% to 20% of their time on projects of their own choosing, and other companies actively solicit suggestions or stage .

To study the effectiveness of rewards, we used a simulation model—an unconventional but powerful tool. A simulation model provides a virtual “laboratory” in which researchers can manipulate every variable of interest (the reward level, say) while eliminating noise such as inappropriate management intervention. Simulated people are programmed to act like real individuals.

Our goal was not to mimic the innovation process at any specific firm, but to develop a model that was as simple as possible without oversimplifying. The virtual organizations we designed consisted only of employees that could search for ideas and a top management that selected the best ideas and shared a part of their value with the inventor. Low-powered rewards typically shared 5% to 10%; high-powered shared roughly 30% or more.

The model’s underlying assumptions are based on past empirical findings—for example, that employees respond positively to incentives but become discouraged by low odds of securing a reward or by being overlooked. We also made sure our model reproduces what we already know about the innovation performance of real companies.

The beauty of a simulation is that once you’ve set it up, you can let it run, much like a Sim City game, and then puzzle out its results, some of which may be surprising. Our model provided valuable insights about incremental innovation in large firms. As our simulated employees responded to their firms’ offer to share a large amount of an idea’s value with them, they put more effort into the search for innovations, and ideas poured forth. The companies were quickly hampered by what we dubbed the “congested project pipeline” effect: Because taking action would have required investing resources such as management attention, the firms were unable to act on most of the ideas that were generated. (This effect doesn’t apply to small firms, where the pipeline rarely becomes congested.)

As employees competed for space in our simulations’ increasingly crowded idea pipelines, more and more came away empty-handed and gave up trying further. This demotivation reduced their effort and prevented them from putting in the time and energy needed to come up with breakthrough ideas.

Could this have been why Google cut back its Founders Awards in 2007, switching to smaller rewards instead? Google hasn’t revealed the reason, but we wouldn’t be surprised.

We found in our model that low-powered rewards such as 10% of the idea’s value produced a healthy number of ideas (the vast majority of them, course, being incremental ideas) without clogging the pipeline or crushing employees’ hopes. Corporate practice seems to bear this out: A recent comparison of the idea-management systems at 105 German firms between 1980 and 2011, for example, suggests that rewards for valuable innovations often range between 5% and 15%. A 2005 survey of 306 German companies showed that ideas yielding a return worth 1.4 billion euros had been rewarded by incentives totaling 159 million euros, or about 11% of the ideas’ value.

Some companies take a tiered approach to incentives. Volkswagen, for example, shares up to 50% of the value of small ideas, but only up to 10% for high-value ideas. That makes sense, because a company can easily act on a lot of small ideas, such as “If we change the position of these two machines, the production process is shortened by one second,” but can implement only a small number of big ideas.

But because breakthrough ideas are so rare, a simple reward system is unlikely to generate many of them. To get more breakthroughs, the best approach is to focus on increasing the variety of ideas that are generated. Past research suggests you might need a culture or organizational structure that encourages play, serendipity, and random interaction. A few companies are experimenting, counterintuitively, with switching the focus from success to failure, rewarding employees who dare to stick their necks out: At Google’s lab X and at WPP’s advertising firm Grey Group in New York, employees can be rewarded for brilliant failures that provide some sort of insight, even if they turn out not to work. Similarly, at the Tata Group’s regional and global innovation contests, a rubric named “Dare to Try” provides rewards for failures that are informative.

Programs such as these help people get over the fear of failure and stimulate employees to stretch themselves—to go far beyond the “acceptable” innovations that they think management wants to hear.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Customer Complaints Are a Lousy Source of Start-Up Ideas

Disarming Landmines Through Strategic Innovation

The Innovation Strategy Big Companies Should Pursue

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

Business Wisdom from the Commencement Speakers of 2014

Commencement speakers face an impossible challenge: to inspire, advise, and entertain, without overstaying their welcome. In the age of YouTube, there’s the added pressure to craft a speech that could go viral, and perhaps even inspire a book. And this year, those invited to take the podium were no doubt aware of the student protests that forced some speakers to cancel.

It’s understandable then that speakers fall back on a similar set of themes: graduates should dream big, failure is part of the path to success, this generation comes to the rescue of a world in need of saving. Nonetheless, several of this year’s speakers put their own unique spin on these and other themes, like Janet Yellen’s inspiring description of her predecessor Ben Bernanke, or Sal Khan putting the profit motive in historical perspective. Others found a fresh angle through their own stories, like Chobani founder Hamdi Ulukaya speaking of the unusual first order he gave as CEO.

What follows is a short recap of some of the best bits from this year’s commencements, as related to business and career success.

Sometimes the hardest part is just getting started

Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, speaking at City Colleges of Chicago

Sometimes big dreams can be overwhelming. It feels like you can’t get from point A to point C. Well the good news is you don’t have to. You just have to get from point A to point B, then from B to C, and so on and so forth. Breaking really big dreams into small steps is the best way to get there… Start by figuring out where you want to go, and aiming high, then take the first step in that direction.

Hamdi Ulukaya, founder and CEO of Chobani, speaking at University at Albany

My first board meeting…they’re looking at me as if I have the magic answers. And one of them, Mike, he says “What now?” I said we’re going to go to the Ace store and we’re going to buy some white paint and we’re going to paint the outside. He said, “Those walls haven’t been painted for the last 15 years, don’t you have anything else to worry about?” I said, But they don’t look good, we need to do something about it. He said, “Do you have any other plan other than painting the walls?” I said, No. But, my friends, one of the best things I’ve done, in summer of 2005, was start painting the wall. I didn’t have a lot of answers… but that summer we painted those walls… Along the way I came up with more ideas… This poet who lived in Turkey Rumi says, “If you start walking the way, the way appears.” And the word that I said, without that much wisdom, that let’s start to paint, was the first very step of Chobani.

(Read HBR’s interview with Ulukaya.)

So don’t focus too much on making plans that you’ll just have to revise anyway

Susan Wojcicki, CEO of YouTube, speaking at Johns Hopkins University

So maybe one thing more to try to remember is plans are made to be broken. You need to be prepared to explore a bit, to make decisions, on what you find, enjoy, discover. I never would have experienced any of that — I never would have discovered that technology could be creative, I never would have started my career in tech, joined Google, led Youtube — if I had tried to stick to a specific plan that I had made when I was your age. The Internet as we know it didn’t exist yet when I graduated. We need to think of our plans as written in pencil, not pen.

After all, the world is changing too quickly

Steve Blank, consulting associate professor at Stanford University, speaking at ESADE

I’d like to start with a request. Everyone, hold your phone up in the air like this. Now look around. In this sea of phones do you see any Blackberries? How about any Nokia phones?… Think about this; 7 years ago Nokia owned 50% of the handset market. Apple owned 0%. In fact, it was only 7 years ago that Apple shipped its first iPhone and Google introduced its Android operating system. Fast-forward to today—Apple is the most profitable Smartphone company in the world and in Spain Android commands a market share of more than 90%. And Nokia? Its worldwide market share of Smartphones has dwindled to 5%. You’re witnessing creative destruction and disruptive innovation at work. It’s the paradox of progress in a capitalist economy. So congratulations graduates – as you move forward in your careers, you’ll be face to face with innovation that’s relentless.

Everyone faces challenges, the difference is in how we respond to them

Jill Abramson, former executive editor of The New York Times, speaking at Wake Forest University

Graduating from Wake Forest means all of you have experienced success already and some of you — and now I’m talking to anyone who’s been dumped, not gotten the job you really wanted, or received those horrible rejections from grad school — you know the sting of losing, or not getting the thing you badly want. When that happens, show what you are made of.

Janet Yellen, Chair of the Federal Reserve, speaking at NYU

There is an unfortunate myth that success is mainly determined by something called “ability.” But research indicates that our best measures of these qualities are unreliable predictors of performance in academics or employment. Psychologist Angela Lee Duckworth says that what really matters is a quality she calls “grit”–an abiding commitment to work hard toward long-range goals and to persevere through the setbacks that come along the way.

One aspect of grit that I think is particularly important is the willingness to take a stand when circumstances demand it. Such circumstances may not be all that frequent, but in every life, there will be crucial moments when having the courage to stand up for what you believe will be immensely important.

My predecessor at the Fed, Chairman Ben Bernanke, demonstrated such courage, especially in his response to the threat of the financial crisis. To stabilize the financial system and restore economic growth, he took courageous actions that were unprecedented in ambition and scope. He faced relentless criticism, personal threats, and the certainty that history would judge him harshly if he was wrong. But he stood up for what he believed was right and necessary. Ben Bernanke’s intelligence and knowledge served him well as Chairman. But his grit and willingness to take a stand were just as important. I hope you never are confronted by challenges this great, but you too will face moments in life when standing up for what you believe can make all the difference.

True leadership isn’t about giving orders…

Jim Whitehurst, CEO of Red Hat, speaking at Campbell University Law School

I see too many leaders who take the short cut – they simply say “go do this because I said so.” That is the simplest way to disenfranchise those with whom you work. You, by virtue of your degree and title, will have positional authority. But I implore you to use that position sparingly. Work to engage those around you. You will be personally more effective, but also gratified by the results you inspire in others.

…it’s about listening to others

Ellen Kullman, CEO of DuPont, speaking at MIT

The hardest thing I had to learn in my career is that I am not always right. I had to develop the discipline to listen. Listening doesn’t always mean agreement. You may continue to disagree, but if you take the time to listen, it will be disagreement for a reason and that tension can lead to understanding and more importantly, to new ideas… This is a particularly important skill for the scientist and engineer to develop, because it can often address our biggest blind spot. Sometimes the science we find so elegant or the technology we feel is so promising doesn’t look that way to others who view the world through a very different lens.

The purpose of business is not just to make profit

Tory Burch, founder of Tory Burch, speaking at Babson College

From the beginning, one of the reasons I wanted to start a company was to start a foundation. Social responsibility was always part of the business plan. This was not always viewed as a positive—some people told me never to mention the word social responsibility and business in the same sentence. That only made me more determined.

In 2009 we launched our foundation to support the economic empowerment of women entrepreneurs and their families. It has been incredibly meaningful not only to me personally, but to our customer, our employees and our business partners, all of whom care about giving back and helping women.

Sal Khan, founder of Khan Academy, speaking at Harvard Business School

Think of the firm not as a tool to maximize profit, but profit as a byproduct of maximizing global well-being, money not as a superficial scoreboard of success, but a command over resources to make the world a better place… Remind yourselves that you are in the eye of the hurricane, in one of the most important times in human history. Imagine living in Athens in the fifth century BCE and only being concerned about your crop yield. Imagine living in 15th or 16th century Florence and only worrying about the next transaction. Imagine living in Philadelphia in 1776 and only caring about your profit. In a thousand years people will romanticize about the time that we live in right now. The time when humanity went from being a fragmented, provincial, unconnected, sometimes petty proto-civilization to being a multi-planetary connected sentient one. The time when the human species awakened. Your grandchildren — and based on what is likely to happen in medicine your great-great grandchildren as well — will ask you what it was like to be alive at the dawn of the awakening of our civilization and what you did to catalyze it.

(Read HBR’s interview with Khan.)

And it’s up to a new generation of more diverse leaders to change the world

Mary Barra, CEO of GM, speaking at the University of Michigan

I noted earlier how the Millennial generation is the largest and richest and most technical, logical generation in American history. What I didn’t say is you’re also the most inclusive and the most optimistic. Use these traits, along with the unprecedented access to information and global communications that we have today, to challenge convention. More than any other generation in history, you have the power to expose and correct injustice, to rethink outdated assumptions, to truly make a difference. And remember while there certainly a lot wrong in this world today, there’s also a lot that’s right. Not everything needs changing. Some things need protecting. And that can be just as important, challenging, and rewarding as changing the world.

Sean Combs, entrepreneur, rapper, and record producer, speaking at Howard University

Your generation is empowered to change the world in ways we can’t even imagine. See right now we are in an epic turning point, a changing of the guard. Our politicians are younger, our entrepreneurs are younger, our faith leaders are younger. The leaders of this generation are more diverse and connected. Your generation crosses cultural lines and breaks gender barriers. I don’t want you to be the next Oprah, I don’t want you to be the next Obama, I don’t even want you to be the next me. I want you to be you.

Being Treated as Invisible is More Harmful than Harassment

Although surveys show that people consider it more psychologically harmful to be harassed than ignored, workplace ostracism turns out to have a bigger impact than harassment, doing greater harm to employees’ well-being and causing greater job turnover, says a team led by Jane O’Reilly of the University of Ottawa. Ostracism is also more common: Of more than 1,000 university staff members, 91% reported such experiences as being ignored, avoided, shut out of conversations, or treated as invisible over the past year, whereas 45% reported being harassed, such as by being teased, belittled, or embarrassed.

What to Do When Success Feels Empty

Why do career “wins” often leave people feeling empty and dissatisfied? And — more important — how can you avoid that problem? We recently asked HBR readers to share their thoughts, and several of the responses call to mind Douglas T. Hall’s classic model of psychological success.

Hall’s model suggests a number of reasons that a success might feel like a failure:

Trade-offs between career and personal goals. This can be as dramatic as going against your deeply held beliefs in order to thrive politically at work or as simple as enduring a punishing work schedule that allows no time for relationships and self-care. Consider this (lightly edited) response to our earlier post, from Jess, who earned a degree in education while running her own business and juggling the demands of her family:

“During this time, my major motivator was the thought that when I was finished, I would have my degree and be more accomplished and successful. However, when I graduated, I felt rather empty. I had divided myself so much during my time in school that I felt I had cheated my family of being present, and though the degree gives me some bragging rights, the close relationships with my children and family are much more noteworthy.”

Lack of ownership. If you don’t believe you are responsible for your win (perhaps you attribute it to luck or other external factors), you won’t feel satisfied by it. It’s not enough to get the big promotion, Hall’s research has shown. You have to believe you’ve earned it.

Lack of validation by others. Others also have to believe you’ve earned your success. This is why many young managers, struggling to move past an “eager novice” image in the companies where they started their careers, end up pursuing growth and advancement elsewhere.

No time to learn. Once you’ve landed the account, gotten the promotion, or made partner, do you have a chance to reflect on what you’ve learned and how to approach your new responsibilities? Or do you start putting out fires right away? Whether your organization sets a manic pace or you do (or both), it’s common to tackle one big challenge after another without taking time for growth in between.

With so much tension between the professional and the personal, how can any of us hope to achieve real satisfaction? One way is what psychologists call generativity: passing along what you’ve learned over the years to help people in the next generation achieve their goals and dreams. As another HBR reader, P.G. Subramanian, put it, “You really succeed when the team succeeds.”

That mind-set is a strong undercurrent in our article “Manage Your Work, Manage Your Life.” Though our research sample of senior executives was diverse in many ways — we synthesized the insights of almost 4,000 men and women from a range of industries, job functions, and nationalities — the leaders in our data set had one important thing in common: They all took time from their busy lives to share what they’d learned with the MBA students who conducted the interviews.

The concept of generativity was first defined by Erik Erikson, who saw it primarily as a midlife concern: Do we succumb to thoughtless routines and selfish pursuits? Or do we make lasting contributions by teaching, mentoring, participating in social systems, raising children, or creating things that will outlast us and benefit future generations?

Though the midlife years are indeed ripe territory for questions like these, even kindergarteners (some more than others) derive great enjoyment from helping and teaching. Highly generative people often note that as children, they became aware of the problems of others and felt moved to take action. Generativity encompasses both social concern and the competence and confidence to act on it. Dan P. McAdams, a major researcher in this field, suggests in his book The Redemptive Self that generative adults are authoritative (not authoritarian), involved parents; that they are likely to be involved in the political process, organized religion, community and civic affairs; and that they have broad friendship and social-support networks. Unsurprisingly, generative people tend to report high levels of subjective well-being.

How generative are you? Take this assessment to see where you stand.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers