Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1414

June 6, 2014

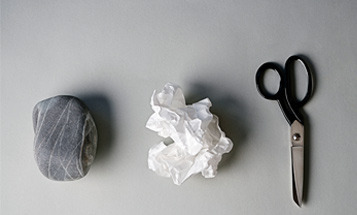

How to Negotiate with Someone More Powerful than You

Going into a negotiation with someone who holds more power than you do can be a daunting prospect. Whether you are asking your boss for a new assignment or attempting to land a major business deal with a client, your approach to the negotiation can dramatically affect your chances of success. How can you make the best case for what you want?

What the Experts Say

“There is often strength in weakness,” says Margaret Neale, the Adams Distinguished Professor of Management at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Having power typically reduces a person’s ability to understand how others think, see, and feel, so being in the less powerful position actually gives you a better vantage to accurately assess what the other party wants and how you can best deliver it. And when you do your homework, you’ll often find you’ve “underestimated your own power, and overestimated theirs,” says Jeff Weiss, a partner at Vantage Partners, a Boston-based consultancy specializing in corporate negotiations and relationship management, and author of the forthcoming HBR Guide to Negotiating. Here’s how to negotiate for success.

Buck yourself up

“Often we get fearful of the threat of competition,”says Weiss. We worry there are five other candidates being interviewed for a job, or six other vendors who can land a contract, and we lower our demands as a result. Do some hard investigation of whether those concerns are real, and consider what skills and expertise you bring to the table that other candidates do not. The other side is negotiating with you for a reason, says Neale. “Your power and influence come from the unique properties you bring to the equation.”

Understand your goals and theirs

Make a list of what you want from the negotiation, and why. This exercise will help you determine what would cause you to walk away, so that you build your strategy within acceptable terms. Equally if not more crucial is to “understand what’s important to the other side,” says Neale. By studying your counterpart’s motivations, obstacles, and goals, you can frame your aims not as things they are giving up to you, but “as solutions to a problem that they have.”

Prepare, prepare, prepare

“The most important thing is to be well prepared,” says Weiss. That involves brainstorming in advance creative solutions that will work for both parties. For example, if the other side won’t budge from their price point, one of your proposals could be a longer-term contract that gives them the price they want but guarantees you revenue for a longer period of time. You also want to have data or past precedents at your disposal to help you make your case. If a potential client says they will pay you X for a job, having done your research allows you to counter with, “But the last three people you contracted with similar experience were paid Y.” Preparation gives you the information you need to “to get more of what you want,” says Neale.

Listen and ask questions

Two of the most powerful strategies you can deploy are to listen well, which builds trust, and pose questions that encourage the other party to defend their positions. “If they can’t defend it, you’ve shifted the power a bit,” says Weiss. If your boss says he doesn’t think you are the right addition to a new project, for instance, ask, “What would that person look like?” Armed with that added information, says Neale, “you can then show him that you have those attributes or have the potential to be that person.”

Keep your cool

One of the biggest mistakes a less powerful person can do in a negotiation is get reactive or take the other person’s negative tone personally. “Don’t mimic bad behavior,” says Weiss. If the other side makes a threat, and you retaliate with a threat, “you’re done.” Keep your side of the discussion focused on results, and resist the temptation to confuse yourself with the issue at hand, even if the negotiations involve assigning value to you or your product. “Know what your goals are and direct your strategy to that and not the other person’s behavior. You have to play the negotiation your way,” Weiss says.

Stay flexible

The best negotiators have prepared enough that they understand the “whole terrain rather than a single path through the woods,” says Weiss. That means you won’t be limited to a single strategy of gives and gets, but multiple maneuvers as the negotiation progresses. If the other party makes a demand, ask them to explain their rationale. Suggest taking a few minutes to brainstorm additional solutions, or inquire if they’ve ever been granted the terms they are demanding. Maintaining flexibility in your moves means you can better shape a solution that’s not only good for you, says Neale, but also makes them “feel like they’ve won.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Put yourself in their shoes — it’s crucial to understand what’s important to the other side

Remember your own value — you are at the table for a reason

Ask questions — you’ll get valuable insight into their motivations and interests

Don’t:

Wing it — nothing beats good preparation

Depend on a single strategy — develop a range of responses to push the negotiation in your favor

Copy aggressive behavior — if they make threats or demands, stick to your goals

Case Study #1: Do your homework

Ben Koeneker knew the odds were stacked against him. Then the head of business development for a midsize Midwest telecom company, he was trying to convince Siemens, the multibillion-dollar electronics conglomerate, to give his firm an exclusive distribution contract for a new business communications product. At the time, his $28 million company was known more for refurbishing than distribution. “We were tiny,” he says. “We were the ant shouting at the elephant.”

Koeneker did copious amounts of research prior to sitting down at the table. He researched Siemens products and why their current channels of distribution weren’t working well. He also made sure he knew that his own company could deliver on every level, preparing counterarguments for any doubts that might arise. “I knew we couldn’t pretend we could do something we couldn’t do,” he says.

When the negotiations began, he emphasized the pros of his company’s distribution model, rather than the cons he felt currently existed in Siemens’ current method. “If you spend too much time talking about the negatives, you’re basically telling them that they’re doing their business wrong.” He also pointed out that signing with his firm would free up money to devote to marketing, which he knew from his research was something that Siemens wanted.

A turning point came when a senior Siemens executive said that while he was impressed with the proposal, he wondered if Koeneker’s company could scale effectively if the product line took off. Two rivals to Koeneker’s firm, the executive said, were bigger and could more easily handle growth. “I turned to him and said, ‘Are those two companies interested in distributing your product at this time?’” Koeneker says. “I already knew the answer from my research that those companies had turned them down.” He followed up by adding that while his firm was small, it was better thought of as “boutique,” with the unique ability to focus completely on the Siemens brand.

Shortly after, they inked the contract.

Case Study #2: Know your value

Management coach Ginger Jenks didn’t want to lose her client. Michael* had asked her to work on a side consulting project, but balked at her proposed fee. Though he had been paying her usual rate for several years, he went into “hard negotiation mode” for the extra work, Jenks says. “He told me he could get someone else for less than a third of my price.”

Jenks valued Michael’s continued business, but she knew she wasn’t willing to lower her rate. “I was fairly confident that he wanted me to do the work,” she says, “and I was certain that I did not want to feel ‘nickel and dimed’ on the project.” She decided her strongest strategy was not to take it personally that he was acting so insulted by her price. “I knew it was just a negotiating tactic on his end.”

When they met again to discuss terms, Jenks held fast to her initial proposal. She knew from hearing him relate stories of past negotiations that he respected strength and tenacity. She also knew that he valued good work above all else, and likely didn’t want the hassle of finding someone new.

At the table, Jenks stressed their great track record together, suggesting that if he could find someone who could do as good a job as he knew she would do, he should go elsewhere. Throughout, Jenks reminded herself that negotiating “is a little like dating,” she says. “If you are too interested, you lose power. But if you can remain calmly interested but still detached, that creates power.”

Michael thought it over for a few days, and then accepted Jenks’s original proposal. “It’s critical to remember that you have something the other person wants also,” she says. “Even if you aren’t in the power position, you have something to offer.”

*not his real name

Focus On: Negotiating

To Negotiate Effectively, First Shake Hands

The Simplest Way to Build Trust

Even Small Negotiations Require Preparation and Creativity

Make Your Emotions Work for You in Negotiations

June 5, 2014

The Secret History of White-Collar Offices

Nikil Saval, editor at n+1, on how gender, politics, and unions have affected the American workplace since the Civil War. For more, read his book, Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace.

Can GM Make it Safe for Employees to Speak Up?

In early April, following the news of faulty ignition switches and recall of more than 6 million cars, GM CEO Mary Barra announced a “Speak Up for Safety” program. “GM must embrace a culture where safety and quality come first,” Barra said at a company town hall meeting. “GM employees should raise safety concerns quickly and forcefully, and be recognized for doing so.” (Since April, the number of vehicles the company has recalled for a variety of reasons has doubled.)

In an industry that involves selling machines that transport humans at fast speeds, the notion that employees wouldn’t be encouraged to discuss safety seems odd. But the company’s transition to a culture that dissuades silence has been slow. As Harvard Business School professor David Garvin explains, “Culture is remarkably durable and resistant to change.” But at GM, and at many other large organizations, the challenges may be especially complex.

As Mary Barra put it to her employees, following today’s release of Anton R. Valukas’s three-month internal investigation, “The lack of action was a result of broad bureaucratic problems and the failure of individual employees in several departments to address a safety problem…Repeatedly, individuals failed to disclose critical pieces of information that could have fundamentally changed the lives of those impacted by a faulty ignition switch.”

In other words, it wasn’t a cover-up or a deliberate attempt to thwart safety; it was just the way GM did business, with “no demonstrated sense of urgency” and “nobody [raising] the problem to the highest levels of the company.” But even though Barra attempted to blame a few “individuals,” her underlying message hints at the importance of company — and industry — culture.

A fundamental problem at many American car companies is a legacy of reacting slowly, protecting executives from bad news, and focusing on cutting costs. And the sheer complexity of building cars also plays a role — David Cole, the former head of the Center for Automotive Research (and son of a former GM president), insists that this is really what’s behind the ignition switch error and why it was so hard for the company to get to the bottom of the problem.

But that’s exactly why it would be a mistake to look past organizational behavior and culture at GM: It is utterly inevitable that things will go wrong, according to Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson. This is “not because people screw up, but because of the immense complexity of what we do,” she told The Washington Post. “The phenomenal number of interacting parts, interacting people and continuing changes in technology mean that we will always have failures, full stop.” (Consider: there are bugs in your smartphone, too – another complex device – but they won’t kill you.)

And yet we have a canon of research and experience telling us that while mistakes always happen, it’s the environment in which they occur that really makes the difference. And it’s really hard for leaders to change that culture, even when they become aware of the problem.

The classic example of repeated institutional failure, of course, is NASA. “If you think about the Challenger space shuttle explosion [in 1986], the incident was attributed to cultural issues: an unwillingness to speak up and accept dissonant voices,” says David Garvin. “Then, 17 years later, we have the Columbia explosion. Culture is tough because it gets embedded.”

Conversely, says Garvin, there are programs like SUBSAFE for the U.S. Navy’s nuclear submarines. “At NASA, you had to prove something was broken, which is hard to do,” he explains. “At the nuclear submarine program, the working mantra is ‘prove to me that it’s right, that it’s workable.’ That’s a very different mindset.”

Each mindset requires very different types of communication — and proving that something works requires raising open-ended questions. In order to show that something is broken, however, you may feel you have to be completely confident in your facts. Garvin notes that this is where Edmondson’s work on implicit voice theories comes into play. These are “theories we have in our heads about the risks of speaking up. Things like: Don’t embarrass the boss in public. Don’t go up the chain of command. Everything must be done before you present it.”

“These theories are hard to dislodge, and you need leaders who explicitly invoke the kind of behavior they’re asking for,” Garvin says.

After the Challenger explosion, there were new requirements put in place, but none of them required major changes to the organization itself. More than a decade later, and under a culture sociologist Diane Vaughan says fell “back on routine under uncertain circumstances,” a piece of foam broke off the Columbia shuttle and hit a section of the wing during liftoff. Repeated requests for photos and data of the shuttle to discern any problems that might occur during reentry were dismissed. In a recent New York Times video on both disasters, one former engineer, Rodney Rocha, recalls asking why his request was rejected. The manager’s answer: “I don’t want to be a Chicken Little about this.”

At NASA, notes Rocha, “part of our engineering culture is that you work through your chain of command. I will regret always why I didn’t break down the door by myself.”

At GM, despite the company’s insistence that its culture is changing, there are a few key sticking points worth examining.

First, Maryann Keller, a former auto analyst, notes that, historically, GM hasn’t invested in root-cause analysis. While working on her 1989 book on GM, she shared this story that an engineer imparted: “They were having a problem with enormous warranty claims for a window washer motor. The original response from GM was not to look for the root cause because that wasn’t part of the company’s thought process. No one asked, ‘Why are they failing?’”

Instead, she said, “their proposal was to build another factory to make window washer motors.” And the reason the motors were failing in the first place? “To save a few pennies, someone had changed the design of the motor so that there was no internal way to cool it. So it had to use the washer fluid itself to cool down.”

Keller notes that root-cause analysis has gotten better, but the lack of it illuminates the industry’s mentality that you “build a car to the specifications that have been accepted for that segment of the market, make sure your bill of materials equals a certain cost, and whatever happens after that is extraneous.” American car companies, she says, have tolerated high warranty claims based, in part, on an attitude that “if something happens along the way, so be it. It’s not my job.”

Second, Keller says that for years it was considered bad for your career if information filtered up to the highest ranks. “I had people tell me that everyone would know about a problem, but no one would speak about it,” she explains. “The goal was to insulate the senior executives and hope that nothing happens.” It’s telling, as the AP reported yesterday, that the director of vehicle safety at GM was four rungs down from the CEO prior to the recall. Both Ford and Chrysler’s hierarchies place safety directors closer to the CEO, and management experts told the AP that “safety ranks higher at other companies as well, especially food, drug, and chemical makers. At some, the safety chief has direct access to the CEO.”

But although changing a corporate culture is hard, it is not impossible with the right leadership. Just take this now-famous story about Ford CEO Alan Mulally. As Fortune first reported:

“Mulally instituted color coding for reports: green for good, yellow for caution, red for problems. Managers coded their operations green at the first couple of meetings to show how well they were doing, but Mulally called them on it. ‘You guys, you know we lost a few billion dollars last year,’ he told the group. ‘Is there anything that’s not going well?’ After that the process loosened up. Americas boss Mark Fields went first. He admitted that the Ford Edge, due to arrive at dealers, had some technical problems with the rear lift gate and wasn’t ready for the start of production. ‘The whole place was deathly silent,’ says Mulally. ‘Then I clapped, and I said, ‘Mark, I really appreciate that clear visibility.’ And the next week the entire set of charts were all rainbows.”

It’s a striking moment, in which a subordinate was allowed to admit failure and the boss praised him for it — something Edmondson says is crucial to developing a culture that can learn from failure and communicate more openly. In a case study related to her research at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis, Edmondson chronicled the efforts of one executive to maneuver workplace norms. As Garvin explained to me, this executive borrowed the concept of blameless reporting from aviation. “If you have a near miss, and you file it with the FAA within 10-14 days, you are exempt from punishment.” He says the hospital executive instituted something similar, and worked to distinguish blameless acts from blameworthy ones to maintain accountability while encouraging employees to speak up.

GM is seemingly not there yet, despite the company’s insistence that today’s culture is markedly different than it was before its 2008 bailout. Sure, Mary Barra told employees, “If you are aware of a potential problem affecting safety or quality and you don’t speak up, you are part of the problem. And that is not acceptable. If you see a problem that you don’t believe is being handled properly, bring it to the attention of your supervisor. If you still don’t believe it’s being handled properly, contact me directly.”

But everything we know about speaking up shows that doing what Barra has asked people to do is completely and utterly terrifying. And while the first steps are important — the Speak Up for Safety program and hiring a new safety chief — transitioning from hiring someone in that role to embedding a safety culture throughout GM is far from guaranteed. “A strong safety culture stems from psychological safety — the ability, at all levels, to speak up with any and all concerns, mistakes, failures, and questions related to even the most tentative issues,” writes Edmondson. “Simply appointing a safety chief will not create this culture unless he and the CEO model a certain kind of leadership.” The stick of firing a handful of people isn’t enough to send the message — the CEO must also use the carrot of publicly praising employees who speak up.

At the same time, many of the people I spoke with are optimistic about Barra’s ability to lead going forward. “You hope a crisis brings change,” says Maryann Keller. “But GM has had a hard time internalizing that past crises were their fault.” And because Barra isn’t from the financial side of the company that’s obsessed with counting beans, Keller hopes she’ll have better insight into how difficult it is to put cars together — how tough it is to talk about things that go wrong.

Our Economic Malaise Is Fueling Political Extremism

The head of the fourth biggest and fastest rising political party in the world’s second most powerful economy is a racist. An aide to the Prime Minister of one of the world’s most promising societies is caught on camera kicking a protestor to the ground. The world’s largest democracy proudly elects a man who rode a wave of religious extremism. The head of yet another is a man whose calls for ethnic purity are becoming more strident. And that’s leaving out the rise of extremist parties in Greece, the U.S., France, and elsewhere.

What’s going on here?

Here’s my crude, rude version of events: history is repeating itself.

We’ve seen this before: a broken financial system that has created huge economic imbalances. Debtor nations that owe creditor nations impossible amounts, who would have to gut their very societies, and the futures of the people in them, to pay off those impossible debts. And debtor nations and citizens alike that are angry — furious — at the injustice of it. Out of this dangerous cocktail rises extremism, and eventually, war.

The great John Maynard Keynes saw all this as plain as day — after World War I, he predicted that a debt-saddled Germany wouldn’t take it lying down. After World War II proved him right — when not only Germany, but other economically gutted nations succumbed to nationalism and fascism — Keynes tried to design a new global financial system, creating the IMF and the World Bank. Their goals were to prevent exactly the vicious cycle above: imbalances, debt, servitude, extremism, and violence. The IMF was to prevent the buildup of debts and credits; and the World Bank was to invest the surpluses of rich countries in poor countries. We can argue, half a century later, about the sins of these great global institutions — yet, contrary to what today’s conspiracists and fantasists believe, they were not created to oppress; but precisely to prevent oppression from darkening into vengeance.

Yet, today, the situation Keynes foresaw is repeating itself — only more subtly. The problem today isn’t a small number of creditor nations, to whom the vast benefits of global wealth are flowing. It is a small number of super rich individuals: oligarchs, monopolists, scions. In a sense, the same problem, of vast, unjust imbalances, has reemerged; this time beyond national boundaries. Today, the super-rich and their empires span multiple nation-states; whisked from home to home and country to country by private transport, they use different infrastructure (who cares if roads and airports are crumbling when you’ve got a helipad?), play by different rules (do tax laws really matter if your assets are all offshore?), and even different methods of wielding political influence (why knock on doors when you can fund your own super-PAC?).

While the super-rich are vastly disproportionately enjoying the fruits of global prosperity, too many are being left behind. What is common in societies with extremists on the rise? The poor and the middle feel cheated — because they are. In the sterile parlance of economics, their wages aren’t comparable to their productivity — but more deeply, their lives are literally not valued in this system. And so they turn, in anger and frustration and resignation, to those who promise them more.

In all these societies, social contracts prize growth over real human development. Economies “grow”; but the benefits of growth are enjoyed vastly disproportionately by a small coterie of people — usually those politically connected; at the very top of a socially constrained pecking order; a caste society. We are told this is capitalism; in fact, it’s a perversion of free markets I call “growthism.” And while the size of TVs and shopping malls may improve for the poor and the middle, life usually doesn’t. They feel stuck — one paycheck away from penury; one illness away from bankruptcy; one dull, meaningless day at a time at a deadening job. The economy may be growing; but their well-being is not improving; they are asked to work harder and harder; but they do not grow smarter, richer, tougher, wiser, smarter, fitter. Their human potential — the one great gift each of us may be truly said to own — is being stifled.

This, then, is a broken global financial system. It is broken in the sense that the social contract it offers is a fools’ bargain; in which the blind pursuit of growth is asking too many to watch too few get unimaginably rich, while their own human potential is thwarted. And as Keynes foresaw, a financial system that breaks down and corrodes social contracts inevitably fuels great tensions between societies. It leads to vicious spirals of extremism, nationalism, and ultimately, perhaps, war. And today, we seem hell bent on playing out that greatest of human tragedies again; judge for yourself where in that downward spiral we appear to be.

So. My story goes like this. Economies stagnate in real human terms; a tiny few get very rich; life stands still for most; economists call it “growth” and declare it success. Stagnation sparks anger: extremists stoke it; and so the world is ablaze in a new age of extremism.

All as predictable as the sunrise.

And yet. Extremists are hucksters: alchemists of prosperity. They promise us something for nothing; plenitude without peace; taking without giving; that all is a zero-sum game; that we must bully and bluster our way into human possibility. And so we are worse than fools if we are seduced by them; we are cowards.

The paradox of prosperity is this. Imagine a lush field that goes fallow. The tribes begin fighting over the last few dried, cracked stalks of wheat. They fight one another tooth and nail. Until, at last, one is victorious. The field is theirs; but there is no longer any wheat; just handfuls of dust. The others starve. They will do anything for the dust. Until one day, a man says: “Why, the dust! It is rightly ours! Let us take it from them!” And so they do. And the spiral of violence and impoverishment never ends.

One day, generations later, the starving tribes wonder: Why didn’t our grandfathers plant another field?

The paradox of prosperity is this. It is at times of little that we must plant the seeds of plenty; not fight another for handfuls of dust. And it is at times of plenty when we must harvest our fields; and give generously to all those who enjoy the singular privilege of the miracle we call life.

(Nope, extremists; that’s not communism — not government redistribution of dust. It is, as Keynes foresaw, just common sense).

I believe a very great deal about the unsure path of human history will be decided in the uneasy years to come. And so I believe our challenge is nothing less than this. A story as old as time; and as familiar as twilight. To stop fighting over fistfuls of dust, and decide to plant another field instead.

The Innovation Strategy Big Companies Should Pursue

The inability of established firms to come up with breakthrough innovations is a truism today. It wasn’t always so. Joseph Schumpeter, the 20th century economist known for heralding the role of innovation in the evolution of society, argued that established firms were best positioned to innovate because of the resources available to them. Edith Penrose, one of the most prominent management thinkers of the 20th century, agreed.

It was the modern combination of internet and venture capital that changed people’s minds, by opening up a new source of breakthrough innovation: high-growth startup companies. With their appetites for high risks and returns, and no legacy systems or brands to encumber them, agile young businesses produced so many breakthrough products and services that they came out ahead, even given a high rate of failure and even though it often took many experiments to arrive at a winning business model. Innovation scholars who studied these new wellsprings of innovation soon came to appreciate the power of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, rich with resources and creative stimulus.

As the idea took hold that innovation comes from the “startup nation,” many established companies ceded the ground, deciding to focus on execution and efficiency instead. It wasn’t long, however, till they realized that these two strengths without innovation were not enough to win.

In reality, established companies never lost the advantages that served them well in past innovations: the much larger set of resources under their control and the extensive networks, often spanning the globe, they could tap. They might be at a disadvantage in hatching breakthrough solutions at the product and service level, but they beat startups in more complex breakthroughs – those that called for creations or transformations of whole markets and industries. Take, for example, the challenge of bringing about any major innovation in healthcare. Yes, we see startups launching ingenious products and services, but established players are taking the lead in shaping the new healthcare market into which these new solutions can be integrated. The same is true in the energy and transportation sectors, and in the realm of “smart cities.” (In some rare cases, such as social networks or internet content marketing, startups launch products and services capable in and of themselves of creating new industries. But in general, the newness of the business behind them imposes important growth constraints.)

Is it possible that large established companies could excel in both parts of the innovation challenge – not only driving the industry change to take advantage of new solutions, but also serving as hotbeds to create them? It is, but it will require creating different environments within enterprises, more conducive to breakthrough, bottom-up innovation.

You’re no doubt familiar with the distinction between breakthrough and incremental innovation. Terms such as the ambidextrous organization have been coined to highlight the difficulty of managing both simultaneously. What makes this especially challenging is that incremental innovation calls for managing knowledge on many fronts, whereas breakthrough innovation is more about managing ignorance. The processes are necessarily different.

There is another important dimension along which business innovations differ. Some come from the top down, conceived in the upper ranks of an organization and translated into execution plans for lower levels to carry out. Others percolate from the bottom up.

Combine these two dimensions and you can imagine four distinct types of innovation. First there are incremental innovations driven from the top – the updates and extensions planned to ensure continuous progress. Second, there are incremental innovations driven from the bottom, which we could call emergent improvements. The third group consists of breakthrough innovations driven from the top: these are strategic bets. And fourth, it is possible for breakthrough innovations to start at the bottom, and constitute strategic discoveries.

A firm choosing to pursue one of these types of innovation would rely on different processes than it would use for another type. A goal of continuous progress would involve formal planning processes yielding specific, demanding goals, while a goal of emergent improvements would call for processes such as employee suggestion collection and brainstorming. A firm wanting to place strategic bets would need processes to test the rightness of the vision and the organization’s ability to execute.

Big companies have all these processes in place. The ones they don’t tend to have are processes appropriate for strategic discoveries. The advantage of the startup ecosystem is that it brings together people with diverse skills and perspectives and allows the good ideas that result from their interchange to gain traction, without hierarchies of decision-makers to quash them. Corporate processes not only neglect but often prevent such breakthroughs.

How would a management team change that? To create a “startup corporation” environment, it would need to put a number of things in place, beginning with a different approach to motivation. People should be inspired by the vision and culture of the company, not compelled by its hierarchy and rewards structure. It would need to provide the stimulus to inspire new ideas: ways to interact with others from a rich mix of backgrounds through interest groups, idea fairs, and collaborative networks. It should attract interesting players from the company’s landscape to discuss and test ideas. Mechanisms would have to be designed to enable these diverse people and ideas to be combined. Methods would have to exist by which experiments would reveal the technology-business model combination that could succeed.

The point here is that breakthrough innovation need not be random: How you innovate determines what you innovate. Luck plays a role, but it favors the prepared mind.

It’s up to managers in big companies, then, to work on this missing part of their innovation capability – building the startup corporation strengths to generate strategic discoveries. Established companies can be at least as great a source of high-growth innovation as new, agile ones. They can be effective in devising breakthrough products and services, and they are uniquely positioned to create and redefine markets and industries. If they can learn to believe this about themselves, perhaps we will see that Shumpeter and Penrose were right all along.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

Google’s Strategy vs. Glass’s Potential

Why Germany Dominates the U.S. in Innovation

How Separate Should a Corporate Spin-Off Be?

Beware the “Smooth” CEO Succession

CEO succession is an inherently bumpy process. Even when the outgoing leader has performed well and seems ready to retire, the transfer of power is fraught with sensitivities. It’s hard for anyone who thrives in the all-consuming job of a CEO to hand over the reins.

So it’s no surprise that many boards work hard to make succession as painless as possible. They adopt processes that have them anticipating the change far in advance, treat the retiring CEO with full respect, and make him or her feel comfortable throughout.

This emphasis on having the transition go as smoothly as possible is a mistake. Consider the trouble it caused for one global company. When its long-tenured and highly successful CEO was nearing retirement, the company’s board readily agreed to his designated successor. But while this candidate had risen up the ranks and performed superbly at every level, he had a serious weakness in his lack of experience dealing with the board and other key external stakeholders. Some directors saw this as a worrisome risk, but kept quiet given the current CEO’s confidence and their own hesitation to ruffle feathers. Further assuaging their concerns was the outgoing CEO’s request to stay on as chairman, an arrangement to which they readily acceded.

Instead of focusing on addressing the weakness, however, the chairman continued to have a blind spot about it. Making matters worse, he never encouraged his protégé to develop independent relationships with the other directors. As a result, the new leader launched into his CEO role never having gained an understanding of key stakeholders’ perspectives or a wayof staying abreast of them. Less than two years after he took over, progress had slowed so much that the board had to go through the highly disruptive process of removing both him and his mentor.

It’s only natural for board members to respect the view of the successful sitting CEO who has the most intimate knowledge of the company, its leaders, and the environment. After all, many of the board members are current or former CEOs themselves and can’t help but identify with the CEO’s perspective. They easily fall into agreement with the leader’s strongly held perspective on the future, and they slip into assuming his or her continuing involvement in the company after a transition.

But even today’s best-performing companies need a hard, fresh look at their prospects for tomorrow. With a successful leader in place, the board inevitably focuses on the glorious past, not the uncertain future. The current strategy, as well as the currently available talent, becomes the default option.

There is a way for directors to ask the tough questions without undermining the sitting CEO or the company. But that means giving up on smooth succession as the overriding goal. It’s time for boards to accept and prepare for the bumps and bruises that come with successions geared to serve the company’s long-term interests — rather than the current CEO’s comfort.

Ideally the work starts as soon as a new CEO arrives. The board emphasizes their interest in ongoing succession planning. While the CEO should own the process for most of his or her tenure – focused on developing a strong bench and informing the board of progress – the board should gradually take on ownership of the process as the timing of the transition nears, usually a couple of years or more before the CEO’s likely retirement. The board has to be ready and willing to dive into potentially challenging conversations with the outgoing CEO about future strategy, the timing of the transition, internal and external candidates, and his or her role in the transition and the future board.

This expectation-setting is key, so the CEO doesn’t see the uptick in board involvement as a sign of disapproval. But the board needs to back up its intentions by doing its own homework. After all, a big reason CEOs tend to dominate the succession process is that they doubt the board’s ability to make a good decision.

An engaged board can manage succession even with a less-than-cooperative CEO. The founder of an industrial company had performed admirably in building his operation into a major industry player. But the board saw that different talents were needed to reach the next level. Three long-time directors that the CEO trusted went to him and strongly encouraged him to set a retirement date. They also insisted on an objective comparison of his favored candidate with other possibilities. When the leader of a growing business unit emerged as better equipped for the company’s future needs, the board went a step further and assessed that leader against some external talent before ratifying the choice.

As the transition date neared, the board reluctantly allowed the outgoing CEO to stay as nonexecutive chairman. But they rejected a variety of requested retirement perks, such as access to the corporate jet. To top it all off, they closely watched how he interacted with the new CEO. After seeing behaviors that undermined the new leader, they had the chairman removed after only a year. While not all of this was smooth, the board had done the hard work of vetting the succession and supporting the new CEO. And the company continued to thrive.

Corporate directors are facing growing regulatory and investor pressures to exert more oversight over succession planning. It’s only natural for them to relax when their companies are thriving. But that’s no excuse for quick agreement to even the best leader’s plans for succession.

The truly great CEOs recognize their limits. They have the humility to expect their boards to challenge them usefully in their thinking on future strategy and succession – and to keep their boards informed enough to do so. Great boards in turn know that their best contribution to the long-term health of their companies is to keep challenging their CEOs in these areas. This can make for a sometimes bumpy road to succession, but a better outcome for the company and its shareholders.

Diversity Is Useless Without Inclusivity

Over the past decade, organizations have worked hard to create diversity within their workforce. Diversity can bring many organizational benefits, including greater customer satisfaction, better market position, successful decision-making, an enhanced ability to reach strategic goals, improved organizational outcomes, and a stronger bottom line.

However, while many organizations are better about creating diversity, many have not yet figured out how to make the environment inclusive—that is, create an atmosphere in which all people feel valued and respected and have access to the same opportunities.

That’s a problem.

Minority employees want to experience the same sense of belonging that the majority does to the group. Indeed, dating back to 1890, William James noted that human beings possess a fundamental need for inclusion and belonging. Research has shown that inclusion also has the promise of many positive individual and organizational outcomes such as reduced turnover, greater altruism, and team engagement. When employees are truly being included within a work environment, they’re more likely to share information, and participate in decision-making.

There are many reasons that inclusion has proved so difficult for most organizations to achieve. Broadly, they tend to stem from strong social norms and the failure to gain support among dominant group members. To understand these issues better, it is useful to look at four dynamics that frequently work against inclusiveness in many organizations.

People gravitate toward people like them. We’ve long known that similarity makes people like and identify with each other. In organizations, leaders often hire and promote those who share their own attitudes, behaviors, and traits. Thus, many organizations unknowingly have “prototypes for success” that perpetuate a similarity bias and limit the pool of potential candidates for positions, important assignments, and promotions.

To counteract this natural tendency, leaders must focus on the systems in place, look at basic statistics, and ask deeper questions, such as: Who is getting hired? Who is getting promoted at the highest rate? Why don’t we have more diversity in various positions or on teams? Who has access to information and who doesn’t? Who is not being included in these decisions? Whose opinions have I sought and whose have I left out? Am I building relationships with people who are different from me?

Subtle biases persist and lead to exclusion. When minority-group employees are hired, they may experience more subtle forms of discrimination such as being excluded from important conversations, participation in a supervisor’s or peer’s in-group of decision-makers and advisers, and may be judged more harshly. I recently completed a study, for example, demonstrating that individuals who were racially different from their supervisors perceived differential treatment in the forms of discrimination, less supervisor support, and lower relationship quality. The findings also suggested that dissimilarity might lead supervisors to favor people who are similar (in terms of race, gender, etc.) and demonstrate bias against people who are different. Researchers refer to this phenomenon as “subtle bias,” which is often a result of unconscious mindsets and stereotypes about people who are different from oneself.

To neutralize exclusion, leaders need to proactively review the access of all groups of employees to training, professional development, networks, important committees, nominations for honors, and other opportunities. Often, employees who differ from the group in power must satisfy higher standards of performance, have less access to important social networks, and have fewer professional opportunities. A recent Monster poll showed that eight out of ten female respondents “believe that women need to prove they have superior skills and experience to compete with men when applying for jobs.” Leaders may need to invest in training to reduce the subtle biases of the workplace.

Out-group employees sometimes try to conform. Often as a coping strategy, those who are different from the majority will downplay their differences and even adopt characteristics of the majority in order to fit in. Female attorneys, for example, might adopt masculine behaviors to foster others’ perceptions of them as successful. But when unique employees move towards the norms of the homogeneous majority, that negates the positive impact of having diversity within the group.

To reduce conformity, leaders need to talk authentically about the issues, seek out, and encourage differences. Leaders should ask important questions such as “What is it like being the only African-American executive?” or “What has your experience been as a female executive?” “How can we leverage your unique perspective more effectively?” While the key is asking the right questions, it is also important to listen to the responses and not react negatively if the leader does not like what he or she hears.

Employees from the majority group put up resistance. Majority employees often feel excluded from diversity initiatives and perceive reverse favoritism. Many companies have experienced backlash when leaders don’t engage majority members in the conversation on diversity and inclusion, explain why change is necessary, and make everyone accountable.

PwC chairman and CEO Robert Morwitz has said that diversity and inclusiveness are major priorities for him personally. Morwitz prefers to serve as a role model and lead from the front. He pushes to have a diverse team on all major issues. Further, he believes that critical thinking comes from inclusion, that is, from the diversity of perspective. Leaders need to put inclusion—not just diversity—at the top of their agendas and mean it. They need to actively talk about its importance, notice when it is present and absent, and set the agenda for the organization.

High Frequency Trading and Finance’s Race to Irrelevance

John Maynard Keynes very famously proposed that the actions of rational agents in a market were akin to a fictional newspaper contest, where entrants were asked to pick who, out of a set of six women, was most beautiful. Those who successfully picked the most popular face would be eligible to win a prize. Keynes asserted that a naive strategy in such a game would be for an entrant to pick based on their own personal opinion of beauty; and that a much more sophisticated strategy would be to make a selection based on the broader public perception of what beauty is. The underlying insight behind the Keynesian beauty contest when applied to the capital markets: that people value a stock not based on what they truly think believe the value is, but rather, on an assessment of what they think everyone else thinks its value is.

It was hard not think about that analogy while reading the latest Michael Lewis book, Flash Boys. It delves into the world of high frequency trading (HFT), detailing the lengths that firms have undertaken to get a speed edge of only tiny fractions of a second. The effect of that edge? Well, to continue with Keynes’s analogy, it allowed the high frequency traders to peek at the ballots others were sending in to the newspaper before they arrived, in turn giving them the ability to cast their votes using information not yet available to the rest of the market.

Lewis’s book, and HFTs in general, have attracted a lot of attention of late. A big part of it stems from a deep and somewhat intuitive discomfort we have with how HFTs make money, and whether that’s at all correlated to the value they bring to society. Lewis does a very effective job of mounting the case that the correlation is not very high. But while that case is made, there is also an argument to be made that HFTs are not as destructive as they are made out to be in Flash Boys. Sure, stealing fractions of a cent on millions of trades isn’t doing anyone any good. But those fractions of cents would otherwise most likely be accruing to the big banks instead of these new, smaller HFT firms. As long as people have been trading stocks, there have been middlemen taking a cut; HFTs just mean that the cut is now captured by those with the fastest computers.

The broader point that has been missed in the discussion around HFTs is that they actually have very little impact on how companies are run. Because HFT firms are holding stocks for milliseconds, they’re not ever in a position where they’re voting on corporate governance issues. They have no real interest in the underlying fundamentals of the stock. As long as the stock is trading — regardless of whether it’s going up or down — HFTs can take their cut. Because of this dynamic, executives have no reason to pay any attention to them when making decisions.

In terms of the real world of building businesses and creating value, basically, HFTs don’t matter.

But that, in turn, is exactly what makes them so interesting. They represent the logical extension of a topic that’s captured the attention of a lot of great business minds for some time: the ongoing battle between those who view companies through the lens of building something, and those that view it through the lens of finance. HBR is running a special section at the moment dealing with just this; asking whether investors are bad for business. Clayton Christensen and Derek van Bever dig in on this topic, and they identify a number of reasons companies are being pressured to act with an increasing short-term focus.

This pressure poses a problem for people who are trying to build something. It’s hard to create something truly valuable — it takes a lot of time. A lot of patience. Many mistakes are made along the way. There’s a fantastic interview with Jeff Bezos where he talks about it: “I think some of the things that we have undertaken I think could not be done in two to three years. And so, basically if we needed to see meaningful financial results in two to three years, some of the most meaningful things we’ve done we would never have even started.”

Now, there are some rockstar CEOs — who oftentimes happen to be founders, such as Bezos, Steve Jobs, Reid Hastings — who have the ability to resist the pressure that the markets put on them. But what about everyone else? Well, it’s becoming increasingly hard to resist that pressure. The financial markets put pressure on you to generate the type of returns they’re looking for: quarterly results. If you’re an executive and your job lives and dies on those results, then you begin to realize that that’s what you need to deliver. Projects that take longer than that to materialize — particularly those that result in an upfront dip in earnings due to investment — get deprioritized.

In effect, financial markets are pushing companies to run a marathon… by having them sprint every lap.

It makes no sense to let such finance-oriented, short-term pressures seep into the economy’s innovation engines. The arguments against doing so continue to mount. And yet, as I was reading Lewis’s book on high frequency trading, I couldn’t escape the feeling that finance itself was making the most convincing argument of all: that given its way, it would reduce itself to computer algorithms, racing to see who can buy and sell stocks the fastest, in the ultimate of zero sum games.

High frequency trading is a different phenomenon from the increasing focus on short term returns by human investors. But they’re borne from a similar mindset: one in which financial returns are the priority, independent of whether they’re associated with something innovative or useful in the real world. What Lewis’s book demonstrated to me isn’t just how “bad” HFTs are per se, but rather, what happens when finance keeps walking down the path it seems to be set on — a path that involves abstracting itself from the creation of real-world value. The final destination? It will enter a world entirely of its own — a world in which it is fighting to capture value that is completely independent of whether any is created in the first place.

What the EPA’s Clean Power Plan Looks Like in Practice

Something reassuring happened Monday after EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy unveiled the Obama administration’s proposed Clean Power Plan, arguably the most important step the U.S. has taken in the fight against global climate change: The S&P 500 and Dow Jones stock indexes rose to record highs. I’ll take that as a sign investors aren’t buying the old scare tactic that federal climate action is bad for the economy. The public, too, understands that we can’t afford not to do this: More than two-thirds of Americans support carbon pollution limits on power plants, according to a new Washington Post poll. The days when lobbyists could kill climate action by trotting out bogus gloom-and-doom economic studies may finally be coming to an end.

Attitudes have changed since 2010, the last time Washington debated serious climate action, and not only because most of us have connected the dots between climate change and the extreme weather events that ravage our communities. Americans — and American companies — have also connected the dots between clean energy and economic growth, with 87% last year saying that developing clean energy should be a priority for the President and Congress.

Renewables are growing faster than any other kindof of power generation, with more solar panels installed in the U.S. over the last 18 months than the previous 30 years combined. The cost of solar and wind are falling rapidly; in fact, a few days before the new EPA announcement, Xcel Energy, which provides power to the American heartland, revealed that it was acquiring extensive wind and solar assets, “all at prices below fossil fuel alternatives.” Policies such as the new EPA proposal, which would establish firm limits on carbon pollution from power plants, will only help accelerate these much-needed market innovations.

There will be time to debate whether the EPA’s proposed targets are sufficiently ambitious. After all, the power sector is already halfway toward meeting its 2030 target of 30% below 2005 CO2 emissions levels. But the beauty of the EPA framework is that, while the limits on pollution are firm, the paths to reaching the targets are flexible. States and power companies can design their own way to compliance using a mix of onsite operational improvements and “beyond the fence” innovations, such as increased reliance on renewable energy sources, low-cost energy efficiency measures, and demand response, which compensates electricity customers for conserving energy.

These solutions aren’t in any way a mystery: They are market-tested, cost-effective, and proven to work, because many states are already doing what the EPA will require. Their success is evidence that the country is ready to meet and beat the targets laid out in the proposed standards.

Fifteen of these front-runner states wrote to the EPA at the end of last year detailing the health and economic benefits they’d achieved. All told, they slashed carbon pollution from electricity by 20% from 2005-2011, led by Washington, which saw a 46% reduction during that period.

California is also delivering some big results. The Golden State’s energy efficiency programs have saved its residents $74 billion over the last few decades and avoided the construction of more than 30 power plants. The state has a successful cap and trade program covering power plant pollution and a 33%-by-2020 renewable energy mandate, the most stringent of the 29 state renewable standards currently on the books.

Meanwhile, in the northeast, the nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) has been operating a cap and trade system covering power plants for several years. The program delivered $1.6 billion in net economic benefit between 2009 and 2011 and is on course to cut region-wide power plant carbon pollution by half from 2005 to 2020. The RGGI states are so pleased with their own success they have emphatically asked the EPA to pave the way for other states to join RGGI or to embark on similar regional efforts.

Low-carbon leadership isn’t just confined to the coasts. Illinois, a state heavily dependent on coal for electricity, has aggressive energy efficiency mandates that require utilities to cut energy use by 2% annually by 2015, as well as a 25%-by-2025 renewables standard has been a boon for the state’s wind industry. A similar renewable standard in Minnesota led to a 900% increase in the amount of wind energy in the state from 2000-2010. In Colorado, the state renewable energy mandate was bumped up from 20% to 30% in 2010. And the U.S. national champion for wind production? Texas, thanks in part to a renewables standard signed in 1999 by then-Governor George W. Bush.

The most exciting action here is coming from dynamic American companies that are developing energy products and services that save consumers money and give them new options. Google’s Nest thermostat, for example, lets homeowners control their appliances remotely to reduce peak load and save money. SolarCity’s groundbreaking solar leasing approach, and SCIenergy’s cost-cutting energy efficiency services for commercial customers, are both changing the energy cost equation.

Since the days of Thomas Edison, the power sector has had but one business model: a power company burned fuel to create electricity, then sent it along inefficient wires to the customers. Today that model is giving way to one in which power and information flow in both directions, and customers not only receive but also produce and store electricity. Given the sheer scale of our energy system, such change doesn’t happen overnight. But the EPA’s Clean Power Plan is focused on where America is going, and designed to help us get there faster.

How to Repair a Damaged Professional Relationship

If you’ve spent enough time in the workforce, you almost certainly have a trail of damaged professional relationships behind you. That doesn’t mean you’re a bad manager or employee; it’s simply a fact that some people don’t get along, and when we have to rely on each other (to finish the report, to execute the campaign, to close the deal), there are bound to be crossed wires and disappointments.

When conflict happens, many of us try to disengage — to avoid the person around the office, or limit our exposure to them. That’s a fine strategy if your colleague is peripheral to your daily life; you may never have to work with the San Diego office again. But if it’s your boss or a teammate, ignoring them is a losing strategy. Here’s how to buck up and repair a professional relationship that’s gone off the rails.

First, it’s important to recognize that making the effort is worthwhile. Obviously it’ll ratchet tension down at the office if you’re not glaring at your colleague every time they enter the room. But resolving this tension will actually aid your own productivity. A core tenet of efficiency expert David Allen’s Getting Things Done approach is “closing open loops” – i.e., eliminating unresolved matters that nag at your mind. Just as you can’t rest easy until you respond to that scheduling request, you’ll have a much harder time focusing professionally if you’re constantly in the midst of fraught encounters.

Next, recognize your own culpability. It’s easy to demonize your colleague (He turned in the report late! She’s always leaving work early!). But you’re almost certainly contributing to the dynamic in some way, as well. As Diana McLain Smith – author of The Elephant in the Room: How Relationships Make or Break the Success of Leaders and Organizations – told me in an interview, “You may be focusing on another person’s downside – and then starting to behave in ways that exacerbate it.” If you think your colleague is too quiet, you may be filling up the airtime in meetings, which encourages them to become even quieter. If you think he’s too lax with details, you may start micromanaging him so much, he adopts a kind of “learned helplessness” and stops trying at all. To get anywhere, you have to understand your role in the situation.

Now it’s time to press reset. If you unilaterally “decide” you’re going to improve your relationship with your colleague, you’re likely to be disappointed quickly. The moment they fail to respond to a positive overture or (yet again) display an irritating behavior, you may conclude that your effort was wasted. Instead, try to make them a partner in your effort. You may want to find an “excuse” for the conversation such as the start of a new project or a New Year’s Resolution, which gives you the opportunity to broach the subject. “Jerry,” you could say, “On past projects, sometimes our perspectives and work styles have been a little different. I want to make this collaboration as productive as possible, so I’d love to brainstorm with you a little about how we can work together really well. Would that be OK with you?”

Finally, you need to change the dynamic. Even the best of intentions – including an agreement with your colleague to turn over a new leaf – can quickly disintegrate if you fall back into your old patterns. That’s why McLain Smith stresses the importance of disrupting your relationship dynamic. In the aftermath of a conflict, she suggests actually writing down a transcript of what was said by each party, so you can begin to see patterns – where you were pushing and she was pulling. Over time, it’s likely that you’ll be able to better grasp the big picture of how you’re relating to each other, and areas where you can try something different. (If you were less vehement, perhaps she’d be less resistant.)

We often imagine that our relationships are permanent and fixed – I don’t get along with him because he’s a control freak, and that’s not likely to change. But we underestimate ourselves, and each other. It’s true that you can’t give your colleagues a personality transplant and turn them into entirely different people; we all have natural tendencies that emerge. But clearly understanding the dynamics of the relationship – and making changes to what’s not working – can lead to markedly more positive results.

Focus On: Conflict

The Best Teams Hold Themselves Accountable

Win at Workplace Conflict

Managing a Negative, Out-of-Touch Boss

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers