Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1416

June 3, 2014

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

At a ThirdPath Institute conference a few weeks ago, a great discussion arose around the fact that workloads tend to ebb and flow, and it’s important to know how to alternate between periods of peak effort and recovery. Before long, someone noted the analogy to high performance in sports, and used a phrase that piqued my curiosity: Corporate Athlete. I loved the term so much I jotted it down, thinking I might make something of it in my writing and consulting. Then I Googled it.

Oops. Apparently, Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz have already made quite a lot of the term corporate athlete, having coined it way back in a 2001 HBR article (I was only 13 years late to the party!) and explored it in a series of best-selling books about engagement, energy, and business success. So much for my plan to unleash it on the world.

But I was all the more glad to find so much work already done on corporate athleticism, because it has a lot to offer my field: the challenges faced by working parents.

Loehr and Schwartz look at how the winners in the world of sports prepare for competition and then apply these techniques to managerial work. They urge executives “to train in the same systematic, multilevel way that world-class athletes do.” No, CEOs are not forced to run wind sprints (although some do). Rather, they are coached in a holistic program designed to help them attain – and sustain– the highest performance at their craft.

What strikes me most in the writing Loehr and Schwartz have done is their frequent use of the word “balance.” In particular, they see great athletes and corporate athletes achieving the right balance across three critical dimensions:

1. Mind and Body

2. Performance and Development

3. Exertion and Recovery

Of course, people trying to succeed both at work and at home are constantly thinking in terms of balance. But perhaps Loehr and Schwartz have given us a more nuanced way of thinking about what needs to be balanced. Using their dimensions, how might someone go about becoming a superstar Work-Life Athlete?

First, let’s think about that mind–body balance. For athletes, the classic mistake to avoid is focusing only on preparing one’s body for the game. Great coaches equip their players to win the mental game as well the physical one. Executives, by contrast, are too likely to grind away at intellectual tasks and overlook that their bodies must be healthy if they are to have the energy to perform well on the job. As Loehr and Schwartz put it, a successful approach to sustained high performance “must pull together [many] elements and consider the person as a whole.” It must address the body, the emotions, the mind, and the spirit.

For work-life athletes, mind-body balance suggests that we should get enough sleep, eat reasonably well, engage in some exercise – and make room in our lives for social interaction, “me time,” and perspective-seeking through reflection and meditation or prayer. You don’t have to be in perfect shape to be good at your job or effective as a parent. But if we neglect our bodies, or spirits, we may not have enough sustained energy for effectiveness in either work or family, let alone both.

The performance–development balance also has a particular relevance to the work-life realm. Athletes know that the vast majority of their effort is spent on development, preparing for the performance they must put in during actual competition. In business, it feels like the proportions are inverted: every day executives must perform, and only a tiny fraction of their time is set aside for “professional development.” But actually, the athlete’s understanding of the balance would make more sense for business people, too. Athletes in their development days focus on individual elements of their game and build their capacity in the fundamentals; on competition days, they pull all the pieces together and push performance to the maximum. Likewise in business, there are those high-stakes occasions when managers can only pull off what they are trying to accomplish by drawing on every competence they have; but between “big game” days, many assignments could be focused on honing particular fundamentals.

Now consider that working parents also have moments when their capabilities as work-life athletes are seriously put to the test and their performance has the greatest consequences. In those moments, they too need to pull together all their resources and abilities to make the right moves. And ideally, they would have prepared for those moments by deliberately developing individual elements in situations where the stakes were not so high.

Anyone who wants to sustain a performance edge needs to figure out how to keep developing new capabilities, and not just keep drawing on existing ones. If this can’t be accomplished through daily tasks, then it requires regularly scheduled time to be set aside. Whether it’s protecting 30 minutes every other day to read up on industry developments, listening to a language-instruction course during the morning commute, or trying a new recipe every week, turning off the performance pressure creates more openness to new approaches and heightens performance in the long run.

This brings us, finally, to the exertion–recovery balance that Loehr and Schwartz see great athletes managing so well. “In the living laboratory of sports,” they write, “we learn that the real enemy of high performance is not stress, which, paradoxical as it may seem, is actually the stimulus for growth. Rather, the problem is the absence of disciplined, intermittent recovery.” For example, in weight lifting, one stresses muscles to the point where their fibers literally start to break down. However, after an adequate recovery period, the muscle not only heals, it grows stronger. Without rest, one ends up with be acute and chronic damage.

In business, demanding projects, with tight deadlines and stretch goals, can be great – but can’t be unremitting. Occasional overwork is a necessity, at work and in the rest of our lives, but chronic overwork robs us of our resilience. This reduces our performance over time, and causes damage in our work and personal lives. Similarly, too many working parents go full-tilt, non-stop to tackle all they have to do without allowing themselves the recovery time needed for sustainable effectiveness. “Recovery” for the work-life athlete might not come when they jump from the demands of one front to the demands of another. It might require taking breaks from the jumping itself. A good start might be to arrange for some standing “no/limited contact” time slots with managers and coworkers (e.g., specifying that no one should expect a response to an email between 6:30 and 9:30 pm). For that matter, why not set “no screen” hours at home, when everyone stays off their phones, tablets, and other devices and is available to each other?

From a management standpoint, we need to rethink the notion that non-performance time is wasted time. Instead, we need to see that recovery is a key component of sustained high performance. This means we must resist continually increasing the time demands we put on our employees and expecting our employees to be constantly “on call” even after hours. We need to encourage our employees to take lunch breaks, relax on weekends, and actually take their vacation days, unplugged (and also do these things ourselves). By helping to strike the right balances, we can build the work-life athleticism we need when the stakes are highest.

Start with a Theory, Not a Strategy

Well-crafted strategies are road maps to places that yield competitive advantage and generate value for the firm. But once you’ve arrived, they don’t take you anyplace else. That’s a problem for companies under continual pressure from investors to find new sources of competitive advantage.

I recently had lunch with the CEO of a large privately held corporation that illustrated this dilemma. After two decades of strong growth, he recognized that that his strategy had run its course. In the minds of his investors, his success was baked into his company’s current value and they wanted to know where he was going to find more.

He presented to me three broad options for growth: diversify into a rather distant, weakly-related industry; develop and sell new services desired by their somewhat narrow set of existing customers; or expand globally into the same services they provide domestically. He asked which I thought made the most sense.

Of course, I did not give him a straight answer. Instead, I suggested that what he needed was a theory about strategy: a mental model about how his company could create value that would help him assess his three options.

In science, a good theory reveals compelling hypotheses that subsequent experiments will validate. A good corporate theory similarly reveals likely hypotheses about how the firm can create most value. It has three components:

Foresight into the future evolution of their industry,

Insight into what is distinctive and uniquely valuable in the composition of assets and capabilities the company possesses; and

Cross-sight into how combinations of internal and external assets and opportunities can create value.

For a company that has a good corporate theory, selecting the right next strategy should not be a problem; the fact that this CEO and I were having such a conversation about such divergent options revealed the absence of a good theory about what strategies were right for his firm.

I’m not going to pretend that it’s easy to come up with a good corporate theory. And, if anything, companies that have comfortable market positions will find the exercise more challenging than most. Microsoft is a case in point. Although it attained a remarkable position almost decades ago, the company has struggled to find new sources of value creation.

In the long run, firms compete not on their strategies, but on the basis of their corporate theories. For the past several years I have asked students ranging from executives to undergraduates the simple question: If you were given $10,000 to invest in Google, Apple, Facebook, or Amazon, where would you invest?

While the pattern of responses varies, most students quickly recognize that their answers have less to do with assessments of current market positions, and more to do with assessments of each firm’s corporate theory.

Each firm is entrenched in a market position quite distant from the others. Apple makes consumer electronics unrivaled in their ease of use. Google offers a search engine unparalleled in its speed and breadth. Facebook supports a social network unmatched in its reach. Amazon features a web store without equal in scope. But each is guided by a very different corporate theory, distinctly crafted as a reflection of the beliefs and current assets of their firm, which informs how they will move beyond their established and fully valued positions.

These theories (ideally) provide a sense of coherence to the growth initiatives that have pushed these firms into quite disparate and increasingly overlapping market space. Indeed, their theories seem to suggest no limit to the potential for strategic collision. Future results of strategic actions will ultimately determine the worth and accuracy of each firm’s theory.

Bottom line, unlike a strategy, a well-crafted corporate theory can take you beyond the one position or advantage. This is not to say that your theory will necessarily be the best one, but at least it will not be dead on arrival.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Boards Can Innovate

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Online Reviews Could Help Fix Medicine

A basic principle of health care is that everyone strongly favors transparency – for everyone but themselves. “Sunshine is the strongest disinfectant” is the oft-used expression that supports putting information out in the open for all to see. That said, every stakeholder in health care gets a bit nervous about exposing their own data. They are quick to cite the potential downsides – that patients will not be able to understand the limitations of the information, that risk adjustment will be inadequate to explain why their performance looks below average, that they may actually be below average.

No one gets as nervous about public reporting as my health care provider colleagues. We worry that everyone else may game the system, cherry-pick patients, or that we might lose patients if the data look less than perfect. It’s safe to say that number of physicians who hate the idea of public reporting is greater than the number who support it.

All of which makes it that much more fascinating that some provider organizations have recently begun putting all their patient experience data – including every patient comment about every doctor – on their Find-A-Doctor web sites. “Every” actually does mean every – the good, bad, and ugly (after removal of those that might violate patient confidentiality). And they are tied directly to the physician who delivered their care.

Why would they do this? The initial response from some commentators was that they were trying to “out-Yelp Yelp” – that is, control the information that was appearing about them on the Web. In truth, the initial idea was less about controlling information than providing more of it. Rather than living with on-line comments generated by a small subset of patients motivated by who-knows-what to write in, organizations like the University of Utah decided that they would survey all patients electronically, and post all their comments. And they would take the chance that more data would provide a better sense of the truth.

The University of Utah health care system was the first in the country to go down this road, and they were rewarded for their creativity and courage with a very pleasant surprise. The result over the last few years has been astounding improvement in their patients’ experience with their physicians. In 2009, only 4% of their physicians were in the top 10 percentile of Press Ganey’s national database for overall patient ratings. By 2013, it was nearly half – 46%.

University of Utah leaders realized that putting their patient information on the Web wasn’t mere marketing – it was creating a powerful motivation for physicians to give every patient the best, most empathic care. Financial incentives to improve patient experience could never have produced this kind of change. What mattered was physicians’ awareness that every patient visit is a high stakes encounter – the biggest event of the patient’s day or even month. As one orthopedist put it, “It forces me to be on top of my game for every single patient.”

Which is, of course, a good thing. And it’s the reason why other providers are going down this road. Piedmont Health in Georgia went live last month, and Wake Health in North Carolina went live last week. Other organizations, some very prominent, are actively planning to follow suit – including some outside the U.S.

To their immense credit, the quality leaders at the University of Utah are helping other providers follow their lead. Some of my more suspicious colleagues have asked, “Why are they doing that? Why don’t they try to preserve the advantage that they have built?” The answer seems to be that they believe their mission requires them to do the right thing. Plus, like all academics, they relish the pride that goes with sharing a patient-centric best practice.

The Utah game plan is simple, graduated, but not glacial in pace. Over four years, they first expanded the amount of data that were being collected. They moved to e-surveying and started sending surveys to every patient after every hospitalization or visit. Armed with more (and more timely) data, they moved to internal transparency, allowing anyone within the Utah system to see anyone else’s data. After physicians got used to the idea of others seeing their data, and realized the vast majority of comments were actually warm and even effusive, Utah went public in late 2012.

The impact on performance at each step was dramatic, and the secret is now out. Other organizations are aware of what Utah, Piedmont, and Wake Forest are doing, and saying, “We have to do that, too.”

As they do, they will be disseminating priceless marketing information about their care – most patient comments are incredibly warm, grateful, granular, and believable. But, more important, they will be helping their physicians live up to their own aspirations about the kinds of doctors they want to be. And patient care will be better for it.

To join the conversation, register for my June 5 webinar with Cleveland Clinic CEO Dr. Toby Cosgrove “Engaging Doctors in the Health Care Revolution.”

New Thinking Leads to a Decrease in Homelessness

Despite a housing-foreclosure crisis and the Great Recession, homelessness in America has declined 17% since 2005 because of a radical change in how states address the problem, according to the Christian Science Monitor. Officials have reversed the old logic of focusing on homeless people’s social problems first and housing needs second; once people are housed, some of their other problems turn out to be easier to resolve. The “housing-first” approach works only if there’s adequate affordable housing, however, so cities like Boston, where the rental market is tight, have seen increases in homelessness.

MOOCs Won’t Replace Business Schools — They’ll Diversify Them

Over the past few years, business school administrators — like other university officials — have been losing sleep over Massive Open Online Courses (or MOOCs), worrying that these low-cost digital alternatives will cannibalize their business model.

As elite business schools have started to offer their own courses through platforms like Coursera, commentators have pointed out that it’s now possible to cobble together an elite MBA for free. Others have argued that executive education programs are likely to be disrupted, as companies weigh the savings they could achieve by directing executives to MOOCs instead. These programs are a crucial source of revenue for business schools. At Wharton, nearly 20% of the annual revenue comes from executive education, while at Harvard Business School 26% does, and at IESE, it is nearly half.

Are these fears well founded? The answer depends on the students participating in MOOCs. If they fit the profile of traditional MBA or executive education enrollees, then the threat to business schools is clear. Our data suggest that this is not the case. At least at present, MOOCs run by elite business schools do not appear to threaten existing programs, but seem to attract students for whom traditional business school offerings are out of reach.

Though a few studies from Harvard, MIT, and the University of Pennsylvania have examined MOOC participants, none to date have focused specifically on those taking business classes. We analyzed data on over 875,000 students enrolled in nine MOOCs offered by the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. This includes a demographic survey with over 65,000 responses. The nine courses consisted of four that introduce the MBA core — Accounting, Finance, Marketing, and Operations Management — as well as Gamification and the Global Business of Sports. These business MOOCs do not appear to be cannibalizing existing programs but do seem to be reaching at least three new and highly sought-after student populations.

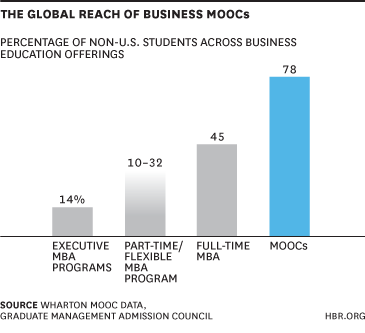

According to the Wharton data, 78% of individuals who registered for an online business course came from outside of the United States. For comparison, Executive MBA programs in 2012 only attracted an average of 14% foreign students. Part-time or flexible MBA programs attracted 10%-32% foreign students, depending on the type of program. Even full-time two-year MBA programs, which attracted 45% foreign students, fall far short of the international reach of these business MOOCs.

It is clear that none of the traditional business education programs can match the global reach of MOOCs, which is all the more impressive when you consider that they are operating at significantly larger scale.

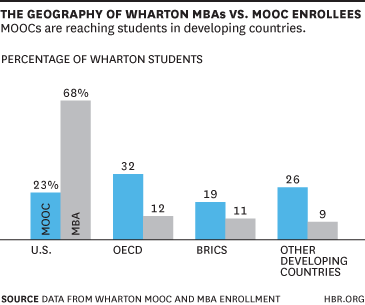

For business schools, then, MOOCs are a tremendous opportunity to expand into underserved markets. Nearly half of the international students enrolled in Wharton’s MOOCs hail from developing countries.

Businessmen and women in developing countries have few sources for high quality management training; there are only five business schools in all of sub-Saharan Africa that have received AACSB, AMBA, or EQUIS accreditation – all in South Africa. They are turning to MOOCs for accessible world-class training.

Even among U.S. enrollees, there appear to be important differences between the population of MOOC students and traditional business school students. First, well-educated foreign-born U.S. residents appear to be overrepresented in business MOOCs. Overall, 35% of all U.S. individuals enrolled in the Wharton business MOOCs are foreign-born, with 54% having a graduate or professional degree. Only 12.9% of the U.S. population is foreign-born. Though MOOC enrollees are quite educated overall, the rate of advanced degrees for foreign-born U.S. enrollees exceeds that of other students.

17%, or one in six, of the highly educated, foreign-born American enrollees in business MOOCs are unemployed, higher than the 13% unemployment rate for native-born American MOOC enrollees. Again, we seem to be seeing groups of individuals who cannot access elite executive education courses obtaining training through MOOCs. And for the unemployed, this may be a way to obtain credentials and skills to enhance job searches.

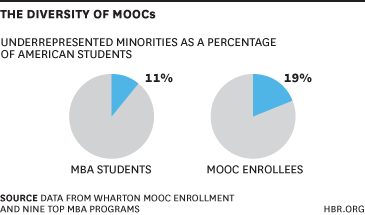

The final group enrolling in business MOOCs is underrepresented minorities. In open, online Wharton business courses, 19% of American students are underrepresented minorities, compared to 11% of students enrolled in traditional MBA programs at nine of the top U.S. business schools. And in terms of absolute numbers, not just percentages, there are vastly more underrepresented minorities online. Across those nine top business schools, that 11% represents just 315 underrepresented minority MBA students, while 19% of the Wharton online business classes constitute 166,552 underrepresented minority students.

Business schools are trying to attract these three groups — students from outside the United States, especially developing countries, foreign-born Americans, and under-represented American minorities. According to the 2012 Application Trends Survey by the Graduate Management Admission Council, these populations were among the most likely to receive special, targeted outreach by business schools. Open, online business courses are reaching them in droves. These MOOC courses might then provide a highly enriched recruiting pool for full-time and executive MBA courses.

One area where business MOOCs are falling short is in attracting female students. While more than 40% of applicants to MBA programs are now women, only 32% of students enrolled in business MOOCs are women. That number drops to 23% in BRICS countries. Women in the developing world face even greater barriers to traditional business training than their male counterparts. Careful marketing aimed at these women might open the door for yet another large population of new business school students.

If business schools want to take advantage of the MOOC opportunity to reach a more diverse group of students, they should seek to better understand those students’ motivations. For instance, lots of previous debate over MOOCs has focused on the relatively low rate of course completion. Indeed, only one out of every twelve students who enrolled in Wharton’s courses were still watching the lectures after eight weeks. Only 5% completed all of the course material and assessments (slightly higher than the 3% rate for non-business courses). And it turns out these “completers” tend to be disproportionately male, well educated, employed, and from OECD countries. Among American students, they tend to be white.

On its face, this finding might seem to undermine MOOCs’ potential to enhance the diversity of business school offerings. But for many students, completing an online course is not the most important outcome. Just 43% of respondents to a pre-course survey administered to nine business and non-business courses at Penn indicated that receiving a certificate of accomplishment was “extremely important” or “very important” to them. Similarly, edX has found that only 27% rank earning a certificate of mastery as extremely important.

Business schools must bear this in mind and move away from a business model of charging for certificates of completion. Instead, they must tailor offerings to the goals of these learners, whatever they may be. This could be as simple as moving to a monthly subscription or “freemium” model for access, or it could mean a more fundamental rethinking of what comprises a “course” online.

It is clear from our research that, rather than cannibalizing business school course offerings and executive education, open, online business courses appear for now to be expanding the overall reach of business education. Even in their infancy, business MOOCs from Wharton are reaching groups of students most commonly targeted for outreach by business schools: working professionals outside the United States as well as foreign-born and underrepresented minorities in the United States.

MOOCs are undoubtedly disrupting higher education. Business schools, like other university institutions, will need to strategically adapt to changing circumstances. But the MOOC disruption may not necessarily be the threat everyone is worried about. In fact, it looks more like an opportunity.

June 2, 2014

What’s Holding Uber Back

As a consumer, I absolutely love Uber. The other week I was at a dinner in a relatively remote part of Singapore. Afterwards, the hotel concierge furiously worked three phones to get taxi cabs to appear for the 15 people who were waiting with growing impatience. I clicked three buttons, and my ride was there in 12 minutes. It’s simple, and it works beautifully.

I also love Uber as a student (and teacher) of disruptive innovation theory, because the challenges the transportation company is encountering as it seeks to expand into new cities helpfully illustrate how to assess an idea’s disruptive potential.

This is important, because companies that adhere as closely as possible to the patterns of disruption have the greatest chance to create explosive growth and transform markets. Those that deviate from the approach can succeed, but they are likely to have to fight much harder and spend much more.

Based on our field work applying Clayton Christensen’s foundational research on disruptive innovation, we look at potential disruptors’ performance in three critical areas.

First, the would-be disruptor should follow an approach that makes it easier and more affordable for people to do what historically has mattered to them. Making the complicated simple and the expensive affordable is why disruptors have the potential to dramatically expand a constrained market or prosper at price points that are far lower than market leaders’.

Uber nails this. Getting a taxi is a maddeningly complex task in cities around the world. Uber’s slick user interface solves the problem in a simple, elegant way. It has had to deal with occasional customer complaints about so-called surge pricing (when the price of a ride shoots up dramatically at times of high demand, such as during major weather events or on New Year’s Eve). But it probably has a more committed user base than any business launched in the last five years.

Next, the innovator has to develop a behind-the-scenes advantage: a way of producing a product or service that seems magical from the customer’s perspective and that is difficult for other companies to replicate. Ideally, the innovator has a proprietary technology that makes the offering simple and affordable, or it has developed an innovative operating model that enables the business to keep its costs radically lower than competitors’ as it scales up. Either (or ideally both) of these advantages helps the innovator defend itself when existing competitors or others inevitably respond by trying to emulate its success.

Uber looks solid here, as well. Its powerful back-end system allows it to manage a real-time network of cars in an extremely simple and potentially low-cost way. It can take advantage of network effects in its operations, since the more drivers it recruits, the more valuable its service become and the more other drivers want to join in.

The final area — and the one where Uber faces clear challenges — is whether the would-be disruptor is following a business model that takes advantage of “asymmetries of motivation”. In simple terms, that means a disruptor is attacking markets that existing companies are motivated to exit or ignore because they are unprofitable or seemingly too small to matter. (We discussed these in detail in Seeing What’s Next.)

Consider the early days of Salesforce.com. The company sold its cloud-based customer relationship management software to small companies that could never afford more-sophisticated applications sold by industry leaders like Siebel. Salesforce.com didn’t compete against these applications. It competed against pen and paper and handmade spreadsheets. In its early days, market leaders felt no pain because Saleslforce.com wasn’t taking away any of their customers; rather, it was creating new ones.

The other way disruptors take advantage of asymmetries of motivation is to build a business model that makes it financially unwise for incumbents to respond. This is at least one reason why Netflix ended up crushing Blockbuster. Netflix’s business model did not require it to charge the late fees that made up the vast majority of Blockbuster’s profits. Naturally companies are unlikely to follow strategies that appear to destroy profitable revenue streams or promise to lose them money.

Uber is following neither of these paths. It targets exactly the same customers that taxi companies want. And customers pay fares that are generally comparable, if not higher, than ordinary taxi fares. Taxi companies therefore are naturally neither motivated to ignore nor to flee from Uber. Rather, they are fighting fiercely with every tool at their disposal, including protests by taxi drivers and legislative action.

Worse, the battle between traditional taxis and Uber has attracted opportunity-sniffing entrepreneurs who want to help the incumbents fight back. For example, one of the most popular apps now in Singapore is called GrabTaxi, which uses an Uber-like mobile interface to simplify the process of ordering a traditional cab. That allows cab drivers to offer many of the conveniences of Uber without being disintermediated. GrabTaxi isn’t trying to disrupt the market; it’s trying to help established companies fight back against entrants.

All of these battles are great for consumers, who get to enjoy simpler, increasingly more convenient solutions. There’s little doubt that Uber will continue to penetrate the markets it targets — particularly with its growing war chest of venture capital funding. But because it appears to be missing a key disruptive ingredient, the fight looks like it will get increasingly difficult and expensive.

The Simplest Way to Build Trust

In the midst of an intense negotiation, it’s hard to know what’s motivating the person across the table — is he willing to cooperate with you to meet both your interests or does he only want to serve his? You need to build trust with your counterpart so you can align your interests and increase the likelihood that he will honor his commitments.

A powerful way to establish trust is to employ one of the mind’s most basic mechanisms for determining loyalty: the perception of similarity. If you can make someone feel a link with you, his empathy for and willingness to cooperate with you will increase.

My favorite example of this occurred outside Ypres, Belgium in 1914. The British and the Germans had been fighting a long and bloody battle, but on the eve of December 24th, the British soldiers began to see lights and hear songs from across the field that separated their trenches from those of their foes. They soon recognized that the lights were candles and the songs were Christmas carols. What happened next was rather amazing. The men from both sides came out of their trenches and began to celebrate Christmas together. Men who had hours before been trying to kill each other were now sharing trinkets and family photos in complete trust that no violence would occur. Why? No one knows for certain, but I suspect that it was because in those moments, the men stopped viewing themselves as British and Germans, and rather saw themselves as fellow Christians. They came to perceive themselves as similar, and that meant they could trust each other.

Now you might think I’ve constructed a fanciful theory for a fluke occurrence. Fair enough. My colleague Piercarlo Valdesolo and I wondered the same, so we set out to study it. Although it made good sense that the mind would use similarity as a metric to decide to whom to be loyal, we had no hard proof. To find out if our suspicions were correct, we designed an experiment that allowed us to manipulate similarity stripped down to its most basic elements in order to see how it would affect behavior. To do this, we brought participants into the lab one at a time for what they believed was an experiment on music perception. They put on earphones and sat across from another person, who was actually an actor working with us. The task was simple; all it required was tapping the sensor in front of them with their hand to the beats they heard over their earphones. The beats were designed so that some participants could see their hands tapping in synchrony with the actor (who had his own sensors and headphones), while others would see random, unsynchronized tapping. Why the tapping? Moving in time is an ancient marker the brain uses to discern who’s similar. It occurs in rituals, in military drills, and in team exercises. If you’re moving in time with someone, it’s a symbol that right here, right now, the two of you are a unit.

After the tapping, we had designed a situation where the participants would see the actor get stuck while completing an onerous task from which they themselves were excused. But before they left the experiment, they were offered the opportunity to help the actor complete the onerous tasks if they so desired.

As we expected, relatively few people (18%) decided to come to the aid of the other when they hadn’t been synchronized. But if they had tapped in synchrony, the number who helped (50%) jumped dramatically. What’s more, the increase in helping was directly tied to how similar participants felt toward the actor. Surprising as it may seem, those who tapped in synch believed they shared more in common with the actor than those who didn’t, even though they had never said a word to the actor.

There’s nothing magical about hand tapping. We’ve found the same effect in several ways, including telling people they shared some esoteric (or even phony) characteristic with another. All that’s required to increase people’s willingness to support each other is any subtle marker of similarity.

Try it in your next negotiation. Find and emphasize something – anything – that will cause your partner to see a link between the two of you, which will form a sense of affiliation. And from that sense of affiliation — whether or not it’s objectively meaningful – comes a greater likelihood of trustworthy behavior.

Focus On: Negotiating

Make Your Emotions Work for You in Negotiations

The One-Minute Trick to Negotiating Like a Boss

How to Negotiate Your Next Salary

Should You Eat While You Negotiate?

How to Win the Argument with Milton Friedman

In 1970, in his famous essay, The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits, Milton Friedman railed against any corporate attempt to promote “desirable social ends” which he argued were “highly subversive to the capitalist system.”

Ever since, folks who have gotten together in gatherings like last week’s Inclusive Capitalism Conference have argued that Friedman is wrong to make the trade-off between shareholders and the rest of society so wholly in favor of shareholders and that greater balance is required in that trade-off.

Yet the fact that they make that argument is precisely why Friedman has won the day for going on half a century, a spectacular success for a social sciences argument. Friedman has won the way a great debater wins — by cleverly framing the terms of the debate, not by brilliantly arguing the logic of the debate once it has been framed.

Because Friedman was so inflammatory in his call for a 100% versus 0% handling of the trade-off, his entire opposition for the entire time since 1970 has focused on making arguments for a number lower than 100% for shareholders. In doing so, they implicitly — and I would argue, fully — accepted Friedman’s premise that there is a fundamental trade-off between the interests of shareholders on the one hand and other societal actors such as customers, employees and communities on the other hand.

Ever since, the Friedmanite defense has been to force the opposition to prove that making a trade-off to any extent whatsoever against shareholders won’t seriously damage capitalism. As a result Friedman is innocent until proven guilty and the opposition guilty until proven innocent. That is why we are exactly where we are nearly a half century later.

Had the opposition been cleverer, it would have attacked the premise from the very beginning by asking: what is the proof that there is a trade-off at all? Had they done so, they would have found out that Friedman had not a shred of proof that a trade-off existed prior to 1970. And they would have found out that there still isn’t a single shred of empirical evidence that 100% focus on shareholder value to the exclusion of other societal factors actually produces measurably higher value for shareholders.

Friedman, of course, didn’t feel the need to assemble any empirical evidence to support his point. An economist falls apart and turns into a blubbing puddle on the floor if you take away the concept of trade-offs because they all started in the same place: the societal trade-off between guns and butter. Trade-offs are a sacred article of faith for economists. You simply can’t be an economist if you don’t consider trade-offs to be a central feature of your worldview.

I am an economist but the training apparently didn’t stick entirely for me. I think I read too much Aristotle along the way and to me he just seems smarter than anyone else I have ever read. What he argued about happiness has more direct relevance to shareholder value maximization than anything an economist has ever written. He maintained that happiness does not derive from its pursuit but rather is the inevitable consequence of leading a virtuous life.

The same applies to corporations. If they make it their purpose to maximize shareholder value, shareholders are likely to suffer because that cravenness turns off customers, employees, and the world in general. If they make it their purpose to serve customers brilliantly, be a fabulous place to work, and contribute meaningfully to the communities in which they operate, chances are their shareholders will be very happy.

That is my premise and I am sticking to it until someone can provide a shred of evidence that the opposite has any validity whatsoever.

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

If your company puts you in charge of developing a foreign market or a new line of business, your challenges are in many ways similar to those facing a startup. Before you can scale the business, you have to understand what your customers really want and value, and how to deliver it to them — and that process requires a lot of flexibility.

In theory, you have decent odds of getting it right. Unlike entrepreneurs working out of the proverbial garage, you can draw on your company’s resources to get things done. But as Steve Blank, Henry Chesbrough, and others have pointed out, that advantage is offset by the daunting fact that corporate innovators have to fight a war on two fronts. Like a startup, you have to get the market fit right, but you also have to fight the corporate systems at the same time, dealing with the rules, procedures, and approval processes that every big company has in place to support its strategy. It is a fight that every manager is familiar with, but nowhere is the challenge bigger than when the existing strategy is not aligned with the demands of the situation you are in.

To some extent, you can secure the necessary flexibility by negotiating it up front. Luke Mansfield, the leader of Samsung’s successful European innovation team, did just that; before accepting the job of establishing the new team, he secured full autonomy along with a three-year grace period in which his superiors were not allowed to ask for results. But up-front agreements can only carry you so far. Even if you are operating as a completely separate legal entity, getting things done requires you to collaborate with the main business — and in that process, you will quickly run into conflicts of interest and clashes with existing rules and regulations.

This is where the concept of stealth innovation can help you. In the research that my co-author Paddy Miller and I did for our book “Innovation as Usual”, we found that successful corporate innovators don’t always stick to the rules. Simply put, sometimes the right thing to do is to stop asking for permission and start bending or even breaking select internal rules, working quietly to help the company succeed in spite of its own control systems.

As outlined in our HBR article on the topic, rules and other control systems are generally there for a reason, and stealth innovation should be used in moderation and with great care. It is best practiced by people who have been with the company for a while and understand which of the internal rules should NOT be messed with. And it requires a constant vigilance to make sure that you don’t get into legal or ethical grey areas or lose sight of the company’s interests. For one, when you operate under the radar, it is imperative to involve some informal advisors and consult with them regularly, so you don’t become blind to your own actions or start taking dangerous risks.

Within the political sciences, the merits of conscientious civil disobedience are well recognized. But in the business world, strategic rule-breaking is still very much a polarizing idea. We can all agree that companies should strive to empower their employees. But empowering people to the extent of accepting that they should sometimes break internal rules, even if cautiously and with good intentions? When we wrote about the topic last year, we saw a lot of strong reactions; one commenter even called it “the work of the devil”. The concerns over stealth innovation were perhaps most succinctly stated by fellow HBR author Chris Trimble, who asked of senior executives, “How many stealth innovators do you want running around in your company?”

The question is reasonable, and if you are a senior leader, it is tempting to answer “zero”. But before you do, consider another question: How many of your CURRENT success stories have come about because somebody bent the rules? If you are like most of the companies we have worked with, several of your existing cash cows were created because somebody bent or even broke a few rules. That aspect of the corporate innovation process is rarely highlighted at awards ceremonies or in newspaper articles, and yet, as any innovator will tell you, it is undeniably there. Yes, breaking rules is risky; but the alternative of relentlessly sticking to them, even when the situation changes, also carries a risk. To deny the potentially positive impact of conscientious rule breaking is to ignore a fundamental truth about how successful companies operate in reality.

To be clear, it’s not that rules are bad. By and large, corporate strategies and the internal rules they engender are good and useful. But like the laws that shape our societies, they need to be interpreted and challenged when circumstances change. When formally established courts interpret laws, they aim to ensure maximum fairness, but they take a long time. In a company that needs to move fast, the interpretation often has to take place in real time, on the ground. Our job as senior managers is not to prevent all forms of rule breaking. It is to ensure that when the rules occasionally need to be broken, the people we put in charge are equipped with the experience, the incentives, and the informal support systems to make the right calls.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Boards Can Innovate

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Closing a Business Gracefully

Our family company, founded by my grandfather in 1880, was an importer and distributor of preserved food products in the Greek market. We had dry goods like sugar, coffee, beans, lentils, peas, and chickpeas. We also stocked preserved fish that we supplied to the mountain villages, many of which which had no electricity: Dutch smoked herrings, salted sardines from Portugal, and salted codfish from Norway, Iceland and Canada, all packed in 50 kilo wooden boxes or jute bags.

When I was a boy, none of our goods were branded; they were all sold in bulk and delivered to grocery stores; competition was all about price. It was not until the mid fifties, when I joined the company after completing my MBA in the US, that all this changed. We started packing products in branded half-kilo and one-kilo plastic bags. We also introduced non-food products to grocery stores, securing the distribution rights for American Home Products and Johnson and Johnson.

Our sales of packaged and branded products rose quickly and we prospered for a while as the first mover. But our industry model was changing as supermarkets started to displace the traditional grocery stores and began sourcing supplies directly. In this new environment there was no longer a viable place in the value chain for the wholesaler, and in order to survive we would have to become commission agents for our suppliers, taking orders from the supermarkets.

In our case, our early move into branded goods had bought us time to adjust, and we could embark on the process of closing down our wholesale business deliberately. But there was a real risk that we would lose a hefty sum in receivables from our eleven thousand grocery clients all over Greece, many of whom, not expecting more business with us, would sit on their debt to us forever. To reduce the chances of this happening, I made it a point to visit as many of the larger customers as I could to communicate in person that we would no longer be supplying them.

It wasn’t just about my meeting the customers, of course. There were too many of them for that. I also had to ensure that our sales force would co-operate. Since many of them would be losing their jobs as a result of our change in strategy, their co-operation could not be taken for granted. To secure it I engaged an employment finding agency to help them find new jobs, and paid them their salaries until they did. I also provided them all with warm personal letters of recommendation.

It wasn’t cheap, but the investment paid off, as we were able to recover the vast majority of our receivables. Better yet, the fact that we had made such a graceful departure positioned us well as a commission agent, a role for which it is important that you have a reputation for fair dealing. Trust, not price, is the differentiating factor.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers