Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1418

May 30, 2014

Reinvent Your Company by Reassessing Its Strengths

Strategic consistency is the hallmark of many great companies. Southwest Airlines’ decades-long strategy of “short-haul, high-frequency, point-to-point, low-fare service” produced what was not only one of the best-performing airlines in the U.S. over the last half-century, but also one of the best-performing companies in any industry. For over 50 years, Wal-Mart has pursued essentially the same strategy of “offering the lowest price so its customer can live better.” Wells Fargo has become the most valuable bank in the world by sticking to its strategy of building a value proposition around selling more products per customer than anyone else. And the essence of Walt Disney’s original strategy remains intact today: to construct a range of businesses — from animated film to fun parks, TV, retail, cruise ships, and more — around a group of engaging, family-friendly characters.

But the corporate landscape is also littered with once-great companies whose strategies became obsolete faster than they were able to reinvent themselves. For example, deregulation killed off icons in the airline business such as Pan Am and TWA. Digital technology overwhelmed Kodak’s once-formidable business in photography. The emergence of e-commerce obliterated the likes of Borders, Circuit City, and Blockbuster. Smartphones destroyed Nokia’s cell phone business. Strategic consistency may be a hallmark of great enterprises, but it hastened the demise of these companies. They needed reinvention, not more of the same.

Smart executives know that sustaining great companies requires both strategic consistency and reinvention. But how do you achieve each without sacrificing the other?

In my experience, the answer lies in being able to answer — and act on — two important questions: what capabilities set your company apart from everyone else? And, are there changes happening in your world that will make those capabilities obsolete or insufficient?

The foundation of strategic consistency is being clear about the capabilities that make your company special. Frito-Lay’s direct-to-store delivery capability, Inditex’s fast-fashion supply chain, and Toyota’s production system took years to hone into true sources of enterprise differentiation. If a company’s leaders understand the capabilities that define its unique identity, they’ll make smarter decisions about what businesses to buy and sell, what markets to enter and exit, what to prioritize in new product development, how to manage costs, where to invest, and all the other choices that are inherent in sustaining a great company.

However, leaders must always ask themselves whether their differentiating capabilities are still relevant. Today, all the major credit card companies are seeking to move from traditional payments to digital commerce. In payments, core capabilities are tied to driving card usage because the economic model is based on card transaction fees; but as they move into digital commerce, most credit card firms are finding they lack a new set of required capabilities — the ability to generate, analyze, and use customer data in order to drive sales and loyalty for their primary customer, the merchants who accept their cards.

Similarly, in big-box retailing, most players have run out of room in their home markets for laying down more super stores, so they are seeking growth by using a small-store format to penetrate pockets of geography that their bigger stores cannot reach. But the capabilities — from merchandising to managing store staff and operating the supply chain — are very different for a small-store format.

Or consider U.S. health care providers: the push for more accountable care will require new business models where risk sharing with private and government insurers becomes more the norm. And, yes indeed, such models will demand a set of capabilities now alien to most care providers. Leaders of any company operating credit cards, big box retailing, or health care should be be saying to themselves, “Yes, changes happening in our world are making our capabilities insufficient, if not obsolete. Strategic consistency is not enough right now; we need strategic reinvention to shore up and bolster the foundation of capabilities that will underpin great performance from the business we will have, not just the business we have today.”

There are a handful of leaders who have successfully managed the tension between strategic consistency and reinvention to survive major changes and create a new life for their companies. Andy Grove pivoted Intel from a memory chip to a smart chip company; Lou Gerstner turned IBM from a hardware OEM to an IT services provider; and Phil Knight transformed Nike from a sports shoe company to a sports licensing company. In each case, the reinvention was about adding new capabilities to those that made the company great in the first place. Thus, neither its reinvention meant the loss of strategic consistency nor did strategic consistency come at the cost of falling behind the changes happening all around it.

Managing the tension between strategic consistency and reinvention does not have to mean taking less of one in order to have more of the other. If you correctly identify the capabilities that make your company great and build your strategies around them, and if you act smartly on the enhancements or additions to those capabilities that your changing world requires, you will achieve the benefits of strategic consistency while also preparing your company for the seismic shifts that are inevitable in every industry.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Boards Can Innovate

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Millennials Are Cynical Do-Gooders

It’s tempting to caricature Millennial workers as bright-eyed idealists, given their loudly stated preference for having a social impact through their careers. Either that or as narcissists only out for themselves. But neither is quite true, according to a new paper from The Brookings Institution. It’s easy to cherry-pick from the data to verify a stereotype about Millennials one way or the other, but the holistic picture painted by the paper is more subtle.

The generation born in the 80’s and 90’s does have an earnest belief that companies should care about the environment and other social issues, but they’re also the least trusting generation on record. And those two impulses aren’t contradictory.

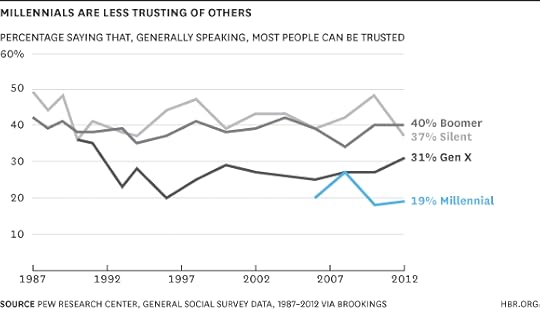

Millennials score lower than any other generation in terms of believing that people can be trusted, and that that cynicism rose in the years following the Great Recession.

Millennials remain scarred by the financial crisis and ongoing tepid recovery (for instance, they keep more than half their savings in cash — much more than older generations do). The Brookings paper, a roundup of existing research on millennials, quotes a UBS report calling them “the most [financially] conservative generation since the Great Depression.”

The tension between Millennials’ hope and their cynicism often gets expressed as pragmatism. They aren’t particularly ideological, but they are attuned to global instability and injustice, economic and otherwise. As the authors put it, “The desire of Millennials for pragmatic action that brings results will overtake today’s emphasis on ideology and polarization as Boomers finally fade from the scene.” Millennials ditched their parents’ ideology but kept their insistence on a better world.

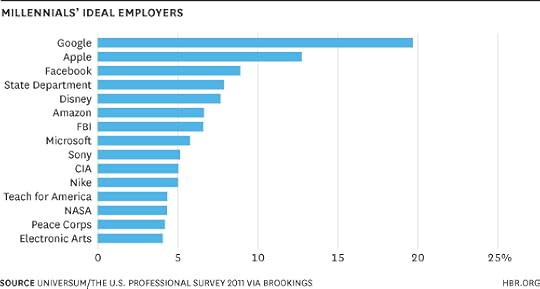

That means prioritizing social goals at work, of course — the paper cites a 2012 survey noting that two thirds of millennial workers said they want their employer to contribute to social or ethical causes. But they want to change the system from within: the organizations Millennials most want to work for include tech giants like Google, Apple, and Facebook, or the government — hard to get more establishment than that. When they are attracted to social impact organizations, they’re those that are designed to be short-term commitments, like Teach for America or the Peace Corps.

In addition, a USC study of Millennials working at PwC noted their demand that companies “make good use of worker’s time, be transparent with them, and provide a supportive work community.”

As this list of demands for corporations starts to expand beyond the environment and social ills to include transparency, engagement, and work-life balance, older generations might be again tempted to write Millennials off as naive. But perhaps younger workers are just expanding the role of the corporation beyond the interests of shareholders.

The Brookings paper cites research from Pew, noting that “about two-thirds of the Millennials surveyed in 2012 also agreed that ‘businesses make too much profit,’ which was the highest level of agreement among all generations.” That’s the thread that ties Millennials’ disparate demands together, even if most of them wouldn’t express them with reference to fiduciary duty.

Today’s younger workers aren’t seeking a revolution. They’re too practical for that. Instead, they’re taking jobs in corporate America and, in the process, insisting that average companies clean up their act. For decades, Wall Street has driven corporations to prioritize shareholder value above employees, the environment, social issues, and sometimes even customers. Now a wary, pragmatic generation is asking for those priorities to change.

The Trouble with a “Jock Culture” at the Office

A few years back, I took over a large research business that was dangerously close to free-falling. Sales had shrunk for 13 consecutive quarters. Many of the best people had left for greener pastures; the worst people had been laid off. One of the board members joked that the only employees left were politically-adept mediocre players. That wasn’t completely true, but it wasn’t totally false, either.

The team I encountered when I arrived was made of a single, distinctive type. They were 100% male, and 100% former jocks–mostly basketball players. Sports permeated the culture. Monday morning staff meetings were spent recounting the weekend’s pro sports games, or their own amateur athletic endeavors. The sports focus created enormous insularity—it was difficult for anyone who didn’t follow the Bruins or the Pats to gain traction in a conversation.

Meanwhile, their business performance was abysmal. These guys would make a forecast on Monday and miss it Friday of that same week.

I wound up replacing that team with a mixture of men and woman with many different backgrounds, effectively breaking up the company’s sports cabal. Soon the jock network was gone. It was not intentional—I never consciously thought, “I need to get rid of the jocks.” I just put in place the folks I though were best, jock or not.

The experience has stayed with me, however. Many companies have strong jock cultures, particularly in their sales departments. Many managers prefer to hire former athletes, figuring that someone who’s put in years of (sometimes painful) hard work to become a high-performer in a competitive sport will show the persistence needed to succeed in non-athletic pursuits, too. In business-to-business selling, entertaining clients at pro sporting events (or on the golf course) is commonplace, so it’s natural that sports fans gravitate to these jobs. (Some of those jobs all but require people to become conversant in sports, even if they’re not really interested.) And in any company, it’s natural for cliques to develop, and for people with similar interests to band together—whether the groups consist of people who do yoga at lunchtime, gossip about reality TV shows, or knit.

Still, I’ve come to believe that having an intense jock culture creates an unusual set of problems. First, the teams are not just dominated by men—they’re almost exclusively men. And anyone who has successfully built teams over the years knows firsthand how crucial woman are to better team performance. Second, the sports metaphors run out of explanatory steam very fast. How many times can you say “We need to keep pushing the ball up-court”? Third, diverse of points of view are lacking. Groupthink sets in, and teams tend to keep pursuing the same strategy, whether it’s working or not. Fourth, this all adds up to an exclusionary vibe. Different types of people are not welcome. If you’re really smart, but a bit different, it doesn’t matter. You’re not accepted, nor do want to join in the first place. This puts the organization on a death path.

In my experience turning around the formerly jock-oriented company, the more I traveled around this business, the more I learned how much its formerly cliquish insularity had been hurting its overall performance. I met many men and women (especially women) who’d concluded they’d never get promoted, recognized for awards, or included in the company’s elite trip to Hawaii (for high sellers) because they didn’t fit in with the jock group. They did what they had to do to keep their jobs—but no more, because they felt demoralized and excluded.

Once the jocks’ control of the culture abated, these workers began to shine. They’d been working at about 70% of their capacity, they told us. Once they were convinced the culture was changing and realized they could be promoted and rewarded, they worked harder. Productivity soared. When a few thousand people increase their productivity by 30%, it has a meaningful impact.

My new leadership team hadn’t anticipated this effect. While we hadn’t liked the culture we encountered when we arrived, we’d seen so many jock-centered cultures during our time in business that we’d become used to them. We hadn’t focused on the culture as the problem—we’d focused on the poor performance. It wasn’t until after we broke that culture that we saw how pernicious it had been—and saw a measurable payoff from working to break it.

To be clear, I love sports. I played in high school and college. (I was mediocre.) I still enjoy going to games of all kinds. I follow the standings, especially in baseball. In fact, a few years ago I took many dozens engineers from foreign countries to Yankee Stadium. They had been fascinated by the strategic aspects of baseball and wanted to see a bit of American culture, and our outing was a wonderful experience.

But being a sports fan is just one aspect of my personality and life. It doesn’t dominate what I think about—not even close. At our Monday morning meetings, sports does come up occasionally. But my team is just as likely to talk about taking our kids to the zoo, a book we finished reading, or a good vacation.

Does Hachette Have any Cards to Play Against Amazon?

The publishing world has been watching the standoff between Amazon and Hachette — at its heart a dispute over contract terms, but one in which Amazon is playing hardball by de-listing Hachette titles — with great interest. Not surprising, since their fight is not only business news, but news about their business. The New York Times has weighed in multiple times, describing the dispute as “clashing visions about the distribution of information in the information age”; so have authors, independent publishers, and Amazon itself. The stakes are big not just for publishers and writers, but for anyone whose products sell through Amazon (a list that’s getting longer every day).

In the June issue of HBR, Ben Edelman addresses perhaps the biggest issue their standoff raises: how less-powerful players (like Hachette) can hold their own against massively powerful players like Amazon (or Google or Apple), who seem to hold all the cards in a negotiation. “Mastering the Intermediaries” suggests four strategies for the Hachettes of this world: exploit the platform’s need for completeness, identify and discredit discrimination, support or create an alternative platform, and deal with customers more directly.

When I checked in with Edelman about this particular fight, he said, “Hachette doesn’t want to lose access to customers who shop at Amazon…but Amazon would be equally alarmed to lose the ability to sell JK Rowling’s popular books [which Hachette publishes]. If Rowling isn’t available on Amazon, customers will need to try another online bookstore. Maybe Amazon isn’t quite as powerful as it thinks.” Which suggests that Hachette could use two of the strategies Edelman recommends: exploiting the platform’s need for completeness and creating or supporting an alternate platform.

“Facing an adversary as sophisticated as Amazon or Google, it’s easy to be despondent,” he added. “But with the right tactics, it’s possible to restore the balance.”

New Research: How Four Talent Practices Add Up to Big Revenue Gains

Too many companies miss out on enormous opportunities for growth and profitability because they don’t appreciate the impact of excellent talent management. Now, research by Gallup clarifies the relationship between firms’ use of four specific human capital practices and their revenue growth. And most importantly, it reveals the power of implementing all four practices together; employers who combine them see substantial additive effects.

If you have studied biology or chemistry, you might be familiar with the term. An additive effect is the precisely measurable boost that occurs when a new intervention pushes things in the same direction as an earlier one. An anesthesiologist, for example, might administer a barbiturate to a pre-surgery patient and then choose to add a tranquilizer, knowing the additive effect it will have on the patient’s relaxation. Interventions aren’t additive when they work against the first effect, or when they are simply redundant and the time and resources spent on them yield no greater effect.

We designed our research to look at four human capital practices previously revealed to be valuable, and discover whether a firm choosing to implement more than one of them would experience additive effects. The answer was a resounding yes. In isolation, these practices are each associated with increasing revenue per employee, but none by more than 27 percent. Combined, however, they drive higher gains – as high as 59 percent when all four practices are in place.

If you do nothing else: select managers with natural talent. Let’s start with the strategy linked to the greatest impact on revenues per employee: the practice of selecting and deploying managers based on their true talent for managing people. As discussed in another post, people can get promoted into management positions for all kinds of reasons (for example, based on years of seniority or to reward standout performance as an individual achiever). But in the most progressive companies, they get the job for only one reason: they are among those few people (about 1 in 10, we find) who have what it takes to motivate and enable teams to do great work.

Whom a company names manager has a ripple effect on everything else. Bad managers drive talented employees away, damaging customer relationships, while talented managers attract and engage the most capable talent. The key to hiring the right managers is to select candidates based on what the job requires – that is, on their ability to inspire employees, drive outcomes, overcome adversity, hold people accountable, build strong relationships, and make tough decisions based on performance rather than politics. The business units we find to be systematically filling their managerial ranks with people who have natural managerial strengths are winning big in the marketplace: they experience 27% higher revenue per employee than the average business unit.

Add to the gains: select the right individual contributors. A 27 percent revenue advantage might sound like plenty, but the big finding of our research is that it is not even half of what companies achieve when they add three other elements to their human capital strategy. An additional 6 percent revenue gain comes when the companies who hire the right managers extend that philosophy to employee hiring. While it might seem obvious that companies would select and develop employees based on their having the natural talents to succeed in particular roles, the reality is that candidates are more often chosen based on generic achievements such as education level, technical skills, and past work experience.

Ideally, with each hire, a company manages to reduce its performance variance and make performance more predictable. The key is to develop a systematic process using assessments that predict future performance. This streamlines the decision-making process, increases productivity, removes bias, improves diversity, and enhances customer and employee engagement.

Push revenue further: engage employees. So far, we’ve seen two practices combine to account for a revenue-per-employee advantage of 33 percent. We can take that up to 51 percent by adding good practices in engaging employees. Here we should note again that we are looking for additive effects. We know that when organizations put naturally talented managers in place, they already achieve higher engagement levels. However, focusing on engagement in itself can produce additional benefits.

Employee engagement initiatives typically begin with a survey to establish baseline metrics and focus attention on what needs to improve. For example, Gallup’s 12-item employee-engagement assessment, the Q12, measures employees’ involvement in and enthusiasm for their jobs and workplace, which links directly to their willingness to go the extra mile for the company and customers. Based on what is discovered, firms devise strategies, establish accountability, communicate progress, and build the data bases that will allow them to do predictive analytics. And as employee engagement rises, companies see gains in productivity, profitability, retention, safety, quality, and customer engagement. Thus a specific focus on increasing employee engagement levels is associated with an additive effect of 18 percent higher revenue per employee.

For maximum payoff: add a focus on strengths. One last major practice in human capital management can be layered on for even greater gains. We know from extensive past research that employees thrive best when they are aware of their greatest strengths and focused on capitalizing on those (as opposed to spending their energy trying to turn their relative weaknesses into strengths). Gallup found that when managers focus on employees’ strengths, 61% of workers are engaged and only 1% are actively disengaged — a dramatically better result than what surveys find of employees generally.

When employees use their strengths, they’re more engaged, perform better, and are less likely to leave their company. And, of course, their company benefits from their relative excellence at the work they do. All this contributes to the additive effect shown by our data: teams who add a focus on strengths to the three human capital practices discussed above see an additional 8 percent higher revenue per employee, for a total advantage over the average business unit of 59 percent.

How many firms are seeing this ultimate additive effect? Unfortunately, very few: from Gallup’s analysis of U.S. organizations, we estimate that less than 1% of teams are given the benefit of all four of these human capital strategies. This highlights an area of tremendous opportunity for any company to accelerate their growth. Businesses can implement the four strategies in whatever order best meets their needs. While the incremental gains might be calculated somewhat differently, the effects will reliably be additive.

The important point is that, in combination, these practices drive increases in everything companies want — more sales, increased productivity and profitability, lower turnover and absenteeism, fewer accidents and defects, and a culture of high customer engagement. Of course, 59% higher revenue won’t happen overnight. But each step pays off in higher human capital capacity, and moves a company along on the path to growth.

Is the Possibility Bias Keeping Us from Having Crazy Fun?

Amateur auto racers aren’t reckless; in fact, they’re more rational about choices than the average population, according to a study by Mary Riddel of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and Sonja Kolstoe of the University of Oregon. Survey results show that racers’ behavior arises not from a devil-may-care attitude but from a relative insensitivity to what’s known as the “possibility” bias, an exaggerated fear of possible but low-probability negative events and an exaggerated expectation of low-probability positive events. The possibility bias, which afflicts the majority of people, leads to poor financial decisions, such as overinsuring against highly unlikely losses and overinvesting in highly unlikely payoffs.

One Reason Cross-Cultural Small Talk Is So Tricky

It was my first dinner party in France and I was chatting with a Parisian couple. All was well until I asked what I thought was a perfectly innocent question: “How did the two of you meet?” My husband Eric (who is French) shot me a look of horror. When we got home he explained: “We don’t ask that type of question to strangers in France. It’s like asking them the color of their underpants.”

It’s a classic mistake. One of the first things you notice when arriving in a new culture is that the rules about what information is and is not appropriate to ask and share with strangers are different. Understanding those rules, however, is a prerequisite for succeeding in that new culture; simply applying your own rules gets you into hot water pretty quickly.

A good way to prepare is to ask yourself whether the new culture is a “peach” or a “coconut”. This is a distinction drawn by culture experts Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner. In peach cultures like the USA or Brazil people tend to be friendly (“soft”) with new acquaintances. They smile frequently at strangers, move quickly to first-name usage, share information about themselves, and ask personal questions of those they hardly know. But after a little friendly interaction with a peach, you may suddenly get to the hard shell of the pit where the peach protects his real self and the relationship suddenly stops.

In coconut cultures such Russia and Germany, people are initially more closed off from those they don’t have friendships with. They rarely smile at strangers, ask casual acquaintances personal questions, or offer personal information to those they don’t know intimately. But over time, as coconuts get to know you, they become gradually warmer and friendlier. And while relationships are built up slowly, they also tend to last longer.

Coconuts may react to peaches in a couple of ways. Some interpret the friendliness as an offer of friendship and when people don’t follow through on the unintended offer, they conclude that the peaches are disingenuous or hypocritical. Such as the German in Brazil who puzzled: “In Brazil people are so friendly – they are constantly inviting me over for coffee. I happily agree, but time and again they forget to tell me where they live.” Igor Agapov, a Russian colleague, was equally surprised to experience the pit of the peach on his first trip to the United States: “I sat next to a stranger on the airplane for a nine-hour flight to New York. This American began asking me very personal questions: was it my first trip to the U.S., what was I leaving behind in Russia, had I been away from my children for this long before? He also shared very personal information about himself. He told me he was a bass player and talked about how difficult his frequent travelling was for his wife, who was with his newborn child right now in Florida.”

In response, Agapov started to do something unusual in Russian culture. He shared his personal story thinking they had built an unusually deep friendship in a short period of time. The sequel was quite disappointing: “I thought that after this type of connection, we would be friends for a very long time. When the airplane landed, imagine my surprise when, as I reached for a piece of paper in order to write down my phone number, my new friend stood up and with a wave of his hand said, ‘Nice to meet you! Have a great trip!’ And that was it. I never saw him again. I felt he had purposely tricked me into opening up when he had no intention of following through on the relationship he had instigated.”

Others are immediately suspicious. A French woman who visited with my family in Minnesota was taken aback by the Midwest’s peachiness: “The waiters here are constantly smiling and asking me how my day is going! They don’t even know me. It makes me feel uncomfortable and suspicious. What do they want from me? I respond by holding tightly onto my purse.”

On the other hand, coming from a peach culture as I do, I was equally taken aback when I came to live in Europe 14 years ago. My friendly smiles and personal comments were greeted with cold formality by the Polish, French, German, or Russian colleagues I was getting to know. I took their stony expressions as signs of arrogance, snobbishness, and even hostility.

So what do you do if, like me, you’re a peach fallen amongst coconuts? Authenticity matters; if you try to be someone you’re not, it never works. So go ahead and smile all you want and share as much information about your family as you like. Just don’t ask personal questions of your counterparts until they bring up the subject themselves. And for my coconut readers, if your peach counterpart asks how you are doing, shows you photos of their family or even invites you over for a barbecue, don’t take it as an overture to deep friendship or a cloak for some hidden agenda, but as an expression of different cultural norms that you need to adjust to.

China’s Tough Approach and a Changing Economic World Order

The international spotlight is on China again, as its behavior in the South China Sea has led to violent protests in Vietnam, rising regional tensions, a flurry of media coverage, and questions about where this is all heading.

We put a few of those questions to Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group and author of Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World. An edited version of our conversation is below.

Do you see the recent actions by China as typical and consistent with their past behavior, or do you think it’s a change, something new and different?

It’s escalatory. The Chinese are dramatically increasing their naval and air capacity in the South and East China Seas. They’re not expanding as a land power, but they see naval power as critical for facilitating their economic ambitions in the region. Their long-term concern is the potential for a Southeast Asian multilateral security framework, potentially aligned with the United States. They see that as dangerous, especially if US/China relations start getting worse.

So they feel there’s a window over the next couple of years to probe and change the status quo ante in the region, and that’s what is happening with this military escalation – and they’ll see what kind of response they get. Recent incidents with Japan and the air defense identification zone resulted in a very significant US response: trips by Secretary Hagel, President Obama, announcements on the US Defense Treaty pertaining to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands issue – ultimately leading to the US and Japan developing a much closer relationship. But the US has made no statement on the South China Sea, where we do not have any defense obligations. And so what I see here is China, vastly bigger than the Philippines and Vietnam, with not only more military capacity, but much more economic capacity and influence over those markets, seeing if they can improve their situation on the ground, and not minding so much if the cost is that a couple of noses get bloodied.

What do you think China’s more aggressive approach means for Western economies and for the world economy?

Look at China 30 years ago and the role it had in global GDP. It was around 2%. Look at it now, and it’s something like 13%. China is close to becoming the world’s largest economy. But when it becomes the largest economy, it will still be poor. It will still be state capitalist. It will still be authoritarian. In other words, it will not share the values and priorities of the United States or our allies in advanced industrial economies. That is an enormous challenge to the economic order.

There’s no question that China is reforming, and that Xi Jinping is engaged in politics of economic transformation that, if successful, will make us cooperate much more closely with the Chinese over the medium to long term. But China is getting bigger faster than it’s reforming, and there is also uncertainty around whether reform will be successful.

All of this means that the challenges that China poses to America and its like-minded allies, from an economic and political perspective, will absolutely grow larger. That can be mitigated – by smart policy, and by the United States having a lot of economic success. But there are also issues between the US and China that are already getting much, much worse. Security for one, because of the rise in the Chinese military and the economy, and their willingness to push. But the second, of course, is cyber, where the Chinese and the Americans are actively at war against each other, and the Americans have had no ability whatsoever to get the Chinese to engage in meaningful dialog in trying to reduce those tensions. So as a consequence, the US has taken the unilateral step of going to the Department of Justice and actually filing charges against five members of the People’s Liberation Army. That will only lead to further escalation, it’s very clear.

You have noted elsewhere all the media hoopla around China becoming the largest economy. But you have also said that this benchmark is not so important to the Chinese, that they have no desire to engage in economic triumphalism. Instead, they prefer a quieter kind of economic expansion. Isn’t that in tension with what they’re doing in the South China Sea, which seems very much like 20th century hardball expansion?

I don’t think those things are inconsistent. The Chinese want to become the largest economy in the world as quickly as possible. They want the rewards and benefits of that to accrue to them as quickly as possible. What they don’t want is to have everyone out there saying, “Oh my God, China’s the largest economy! We’d better do something about it!” Right? So they absolutely want to change the rules of the road through their real power and influence. But they don’t want a bunch of reports publicly saying, “Hey everyone, look. China’s number one.” They understand that they’ve got to be more responsible. They have to play more of a leadership role. They’ve got to put money into dealing with climate. They have to put money into dealing with collective security issues.

Now if it were Russia, that would be different. If someone did a report and it claimed that Russia was the largest economy, you’d have Putin touting that all over the world out of insecurity. The Chinese aren’t insecure. The Chinese want to get as big and powerful as possible before the folks that could stop them might start taking measures that could be damaging to them.

You recently tweeted that the clear winner from the US/Russia fight over Ukraine is China. How so?

The Russians and the Chinese have been negotiating the recent huge energy deal for over ten years. It went on and on and didn’t get done. Now it’s done. The reason it wasn’t getting done for all that time is they weren’t coming together on price, and the Russians were not willing to compromise. What’s changed? The Russians are now under a lot more pressure – from the Americans in particular, but also from the Europeans – and they want to show very strongly that the American policy of isolating the Russians is going to fail. So it was extremely important, politically, for Putin to get this deal done with the Chinese. And it is a massive deal: $400 billion, providing natural gas over 30 years. It definitely shows that the American policy has failed on Ukraine. It also shows that the Chinese are clearly in the driver’s seat here.

[Making money is] not the reason the Russians are doing this. They’re doing it because they feel like they need to show strength, and tying this knot with the Chinese is a wonderful way to do that.

How does China view international economic development differently than we do in Western economies?

The Chinese have absolutely learned that providing lots of money for development-related activities in poor countries is a great way for them to build goodwill and for them to get outcomes that they want. But unlike American development, this is not conditionally linked to democracy or economic advancement or modernization. Chinese development money – and there’s a lot of it, the Chinese development bank, UCDB, gives more money internationally than the IMF and the World Bank combined –constitutes a quid pro quo for decision making that supports Chinese economic objectives directly. So they’re going to help you build a stadium. They’re going to build hospitals. They’re going to build roads. They’re going to give you a power grid. But this is what they want in return. And it’s a very clear list.

So there is no pretense towards development for poor countries and their economies to become strong and self-standing?

No, the Chinese are not, in my view, trying to make these countries strong and self-standing. Now, of course, the Americans don’t always do that [either]. The argument I’m trying to make here is, the fact that the Chinese don’t do as we do doesn’t mean that the Chinese are bad. It means that the Chinese are at a very different level of development with a different economic and political system, and it should surprise us very much for the Chinese to act any differently than they do. So, for instance, when we tell the Chinese we want them to be responsible stakeholders in the global community, the logical Chinese response is: Wait a second. So you want us to act like a rich country, even though we’re a poor country, and you want us to support rules and norms that you created to benefit like-minded countries, of which we are not one. It makes no sense for China to do that.

So in light of what’s been happening in Southeast Asia specifically, and some of these broader dynamics more generally, how should people who are running companies be thinking differently in terms of the risk profile in the region? Is the threshold rising for a destabilized environment there?

I don’t see war between China and Vietnam, or China and the Philippines. As I said, I think the Chinese are pushing and probing in this new phase, and if they get whacked, then they’ll recalibrate. I don’t think this will have a huge impact on investors or multinational corporations on the ground in the near term. Longer term, as China continues to grow, if reforms fail or if they become more antagonistic towards the West, then I expect the ability of Western multinationals to do effective business on the ground in these countries will deteriorate greatly.

The biggest problem I see is a growing paradox: not only is China going to be the world’s largest economy, but out of the top 20 economies in the world, China likely has the largest variance in terms of how attractive it will become for Western investors over the next, say, ten years. At the same time, the Chinese are engaging in fundamental economic transformation, unleashing forces that might lead to a China that can work well with us, or could possibly lead to the collapse of the system, or enormous xenophobia and nationalism. The vast majority of American and Western multinational CEOs are unwilling to think about this, and are just not investing. They don’t think they’ll be in their corporations that long, and they don’t want to deal with that core uncertainty and its implications.

May 29, 2014

Cross-Culture Work in a Global Economy

Erin Meyer, affiliate professor at INSEAD and author of The Culture Map, on why memorizing a list of etiquette rules doesn’t work. For more, read the article, Navigating the Cultural Minefield.

Win at Workplace Conflict

No matter how sound or well-intentioned your ideas, there will always be people inside — and outside — your organization who are going to oppose you. Getting things done often means that you’re going to go head to head with people who have competing agendas. In my career studying organizational behavior, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing some incredibly effective conflict management techniques. I’ve distilled a few of them into some rules for dealing with organizational conflict:

1. Stay focused on the most essential objectives.

It’s easy to become aggravated by other people’s actions and forget what you were trying to achieve in the first place. Here we can learn a lesson from Rudy Crew, a former leader in the New York City and Miami-Dade County schools.

When Crew was verbally attacked by Representative Rafael Arza, a Florida legislator, who used one of the nastiest racial slurs to describe Crew, an African-American, Crew filed a complaint with the legislature but then essentially went on with his work. As he told me at the time, a significant fraction of the Miami schoolchildren were not reading at grade level. Responding to every nasty comment could become a full time job but, more importantly, would do nothing to improve the school district’s performance. Arza was eventually expelled from the legislature. Crew’s takeway? Figure out: “what does winning look like?” If the conflict were over and you found that you had won, what would that look like? Which leads to the second rule…

2. Don’t fight over things that don’t matter.

For a while, Dr. Laura Esserman, a breast cancer surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and a leader of fundamental change in breast cancer treatment and research, was sponsoring a digital mammography van to serve poor women in San Francisco. The sponsorship was taking a lot of time and effort — she’d had trouble raising money for the service after the Komen Foundation had reneged on a pledge of support. Her department chair was worried about the department’s budget and why a department of surgery was running a radiology service. The hospital CFO was not interested in funding a mammography service that would generate unreimbursed care while the university was raising debt to build a new campus. And Esserman herself did not (and does not) believe that mammography was the way forward for improving breast cancer outcomes. After figuring out that sponsoring the mamo-van was absorbing disproportionate effort and creating unnecessary conflict with important people inside UCSF, Esserman offloaded the van. It smoothed the relationship with her boss and allowed her to focus on higher-leverage activities.

3. Build an empathetic understanding of others’ points of view.

As the previous example illustrates, sometimes people fight over personalities, but often they have a reason for being in conflict. It helps to understand what others’ objectives and measures are, which requires looking at the world through their eyes. Don’t presume evil or malevolent intent. For example, an ongoing struggle in the software industry has centered around when to release a product. Engineers often want to delay a product release in the pursuit of perfection, because the final product speaks to the quality of their work. Sales executives, on the other hand, are rewarded for generating revenue. It’s therefore in their best interest to sell first and fix second. Each is pursuing reasonable interests consistent with their rewards and professional training — not intentionally trying to be difficult.

4. Adhere to the old adage: keep your friends close, and your enemies closer.

The late President Lyndon Johnson had a difficult relationship with the always-dangerous (because he had secret files on everybody) FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover. When asked why he spent time talking to Hoover and massaging his ego, Johnson was quoted as saying: “It’s probably better to have him inside the tent pissing out, than outside the tent pissing in.” This is tough advice to follow, because people naturally like pleasant interactions and seek to avoid discomfort. Consequently, we tend to shun those with whom we’re having disagreements. Bad idea. You cannot know what others are thinking or doing if you don’t engage with them.

5. Use humor to defuse difficult situations.

When Ronald Reagan ran for president of the United States, he was (at the time) the oldest person to have ever been a candidate for that office. During the October 21, 1984 Kansas City debate with the democratic candidate, Walter Mondale, one of the questioners asked Reagan if he thought age would be an issue in the upcoming election. His reply? “I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

Let’s face it: you’re going to have conflict in the workplace. It’s unavoidable. But if you keep these simple — albeit difficult to act on – rules in mind, you’ll learn to navigate conflict more productively.

Focus On: Conflict

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Conflict Strategies for Nice People

Senior Managers Won’t Always Get Along

When Your Boss Is Too Nice

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers