Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1422

May 23, 2014

What It’s Like Being a Business Traveler in Iran

It is not easy to visit Iran these days – less than a thousand visas have been granted to Americans over the past 12 months. But with a sense that a new dialogue may be happening between this remarkable culture and the West, about a dozen CEOs from the U.S., U.K., and Canada with extensive experience in emerging markets persevered to take a closer look. We were secured in something of a bubble seeing sometimes what our guides, some explicitly working for the government, wanted us to see. Still, throughout our ten days this month in Tehran, the religious center of Qom and historic Kashan, Isfahan, and Shiraz, little of what we experienced was expected.

We came, of course, colored by the Western news cycle narrative. Iran, for us, was the Iranian Revolution and hostage crisis from our youth, decades of Cold War diplomatic tit-for-tats, and a regime bent on suppressing its own people while actively supporting instability in the region. But after spending the past two years traveling across the Arab world (and writing a book about innovation and entrepreneurship in the region), I also knew how younger generations and new technologies can redefine business and engagement across the board.

We almost immediately learned that Iran is an astoundingly lovely place, with very little of the deep poverty one sees intertwined into the societies of most emerging markets. We visited some of the greatest historic and cultural centers we have ever seen. There is an excellent education system – their engineering, in particular, is globally competitive. We didn’t see a fraction of the religious tension we expected. Everywhere we went, people (especially young people) came up to us even on the streets, tourist spots and restaurants to say hello, to thank us for being there, to express affection.

We met with a wide cross-section of Iranian business leaders, start-up entrepreneurs, clerics, students, and others, and we heard very different perspectives. When history came up at all, which was infrequent, they recalled western-backed coups, our willingness to turn a blind eye to the corruption and human rights violations of leaders we supported, our policies of regime change and our inconsistent follow-through in the region up to the present day.

At the same time their frustration at their own top-down government weight of the last 40 years was equally palpable. Even while we were often monitored, we regularly heard across generations a sense of deeply missed potential and yearning for different futures. “You are impressed by what you’ve seen, that it is better than you expected,” one CEO of a large enterprise told me, “But I can’t help wondering where we’d be today without the tensions, the sanctions, and the missed opportunities.”

Sanctions have clearly had a significant toll – devaluations have had enormous impact on purchasing power, job opportunities across the board are limited, and inflation is improbably high at over 30% – but we were told repeatedly that the banking sanctions were the most effective. For manufacturing equipment, building materials, and consumer goods, however, there were myriad ways (legally and illegally) to work around them, especially through Turkey and Dubai. Coke and Pepsi were everywhere. In oil and gas, where Iran ranks fourth and first in the world respectively, alternative non-western markets have kept their economy marginally afloat for the time being. China was everywhere in big ways and small – sadly it was near impossible to find a real Iranian piece of jewelry or textile in the ancient and bustling bazars.

Stuxnet, the computer virus that attacked much of their security apparatus several years ago, was a wakeup call and the country has since invested significantly in their technology infrastructure. Today, in a country of roughly 70 million, there is well over 100% mobile penetration – meaning many people have more than one “dumb” phone – but 3G is coming and their over 60% Internet penetration is rising (albeit service speed is slow by western standards.)

Even the government has become more proactive in supporting innovation through dozens of tech “incubators” emphasizing technology that fits their economic planning for oil, gas, agriculture, education and city infrastructure. At the same time, there is a rising independent start-up community as well. The recent “Startup Weekends” have attracted nearly 2,000 kids in Tehran looking to learn entrepreneurship and innovate. And despite the sanctions and difficulty in buying apps, we were told that there are some 6.5 million iPhones in the country. Despite government restrictions for access to social networks, every young person we saw has found works-arounds to access Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and more.

One executive said, making an analogy to one of the fastest growing emerging markets of the last twenty years: “Think of us like Turkey a decade or two ago – only Turkey with enormous oil and gas reserves and a hungry and highly educated new generation wanting different lives and to move more quickly.”

And here lies the most central point.

I found that in Iran the difference in outlook between the older and the younger generations could not be wider. The new generations were born after the taking of our Embassy, so it’s not part of their world-view. They have little interest in their parents’ politics or religion, and in being told what to do. They experienced a rigged election five years go and the subsequent brutal crackdown when they protested, and they mistrust anything they cannot prove. They see what other young people are doing around the world with and through technology, and they want to do the same things.

What would happen if Iran’s and Western policymakers embraced this potential, bubbling just an inch below the surface? There are risks. We can’t know precisely what Iran will do in the coming months or years, but we do know with complete certainty that there will be a lot more technology in a lot more hands of the new generation. Bottom up, they will solve problems with new tools and build new economic futures for themselves. The risk in opening up dialogue to be on their sides thus also offers a staggering opportunity – for Iran, the region and globe.

May 22, 2014

How to Manage Wall Street

Sam Palmisano, former CEO of IBM, on striking a balance between running a company for the long term and keeping investors happy. For more, read the interview, Managing Investors.

Find Quiet (and Maybe Even Peace) at Work

My uncle has a farm in Meriwether County, Georgia. When I was a kid, I spent weekends there camping, fishing, and spending time with family and friends. It was my place to wonder and wander. In a time before mobile devices, I could lie in the grass looking up at the stars and experience real solitude and silence. There were no car engines or text message alerts. The silence created space for reflection and imagination.

On a recent workday, in contrast, a venue near my office held an all-day rock concert that shook the windows in my office with sound checks and live music from 9 a.m. until I went home. The previous day I’d made a day trip to New York — a 16-hour cacophony of jet engines, pilot announcements, car horns, and strangers talking loudly into mobile phones. My experiences are not unique. Most of us now live and work in noisy environments. The ubiquity of electronic devices and the density of the cities in which we live mean that few of us regularly experience silence.

All this noise is bad for us. Julian Treasure, chairman of the Sound Agency, has documented a number of these impacts in detail (PDF), noting, for example, that according to the World Health Organization 40% of Europe is exposed to noise levels that could lead to disturbed sleep, raised blood pressure, and potentially increased incidences of heart disease. The European Commission has estimated the total health and productivity costs of road traffic noise in Europe alone at €30–46 billion. And one study indicates that one in three Americans now suffers hearing impairment as a result of noise in the environment. Stephen A Stansfeld and Mark P Matheson (PDF), in a similar roundup of the health impacts of noise, note many of those highlighted by Treasure as well as high incidences of good old-fashioned “annoyance” in adults and children.

Some studies also link noise to decreased performance in the workplace or classroom. Treasure, for example, claims that open office environments in which workers overhear other conversations can reduce productivity by 66%, and classrooms with high noise levels may prevent kids from hearing 50% of what is taught. Aircraft noise near schools has been associated with impaired reading comprehension.

Yet, for all of this evidence, most of us remain ensconced in noisy environments. So what can we do to recapture silence and, in doing so, our health and productivity? Here are a few suggestions:

Properly design your home or workplace. Open office environments may have a number of benefits for collaboration, efficient space usage, and office culture. But due to noise levels and interruptions, they can negatively impact concentration. Similarly, air conditioners, heating units, and electronic devices are critical modern conveniences, but the background noise they create can hinder performance and health. Proper design offsets these impacts. As Cornell’s Lorraine Maxwell notes (PDF), if an office is going to be open, it should contain small, closed spaces available for periods of intense focus. And choosing the right carpeting, furniture, and even ceiling height at home or work can mute the impact of increased noise. The “architectural option” might seem extreme, but for organizations or individuals so motivated, it could work wonders.

Close the door; turn off the TV. Recently, I noticed a bad habit I’ve developed when traveling for business: Almost as soon as I’d get into the hotel room, I’d turn on the TV, just to have a little background noise. Speaking with friends and colleagues, I’m not alone. Many of us reflexively fill silent spaces with music, radio programs, or television shows. Or, we allow the well-intentioned temptation to maintain an “open door policy” in the workplace to prevent us from quietly focusing with deep concentration on the task at hand. There are times for TVs, open doors, and stereos. But there are also times for silence, and to be healthier and more effective, we’d do well to make space for both.

Put in your earplugs. A classic response to unwanted noise is to replace it with wanted noise. As a student, for example, I commonly played everything from ‘90s rock to classical music in my dorm room while studying. And music can have its benefits. At least one study suggests Mozart for those seeking focus, and music has been linked to stress relief and relaxation. But additional research shows that while emotionally satisfying, music may actually decrease a person’s capacity for recall. So for common noise relief, the simplest answer may be to block it with earplugs or noise-canceling headphones.

Take a noise retreat. Even if you can’t cut down on the noise in your daily life, you can find periods of respite. For me, that’s still escaping to my uncle’s farm, to the beach, or to the North Georgia mountains. For others, it’s taking advantage of “silent retreats,” where participants go to actively avoid speaking or experiencing other man-made sounds. Ecologist Gordon Hempton has found only 12 spots in the U.S. free of human-made noise for intervals of 15 minutes or more, but there are a number of resorts that promise as much escape from noise as possible without a long hike into the Alaskan wilderness.

It’s ironic that, as more of our tasks become mental, our environments make the concentration so necessary for intellectual labor more difficult. The noise permeating our environments can impact our health, concentration, and happiness. As silence becomes rarer and more valuable, we’d be wise to seek it out.

Conflict Can Jeopardize Your Health

People who said in response to a survey that they “often” or “always” experienced conflicts with people in their lives were 2 to 3 times more likely than average to be dead 11 years later, according to a Danish study of nearly 10,000 middle-aged adults. The deaths were generally from illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and alcohol-related liver disease, according to The Atlantic. So although isolation is a risk factor for disease and death, social interaction isn’t a good antidote if it’s fraught with conflict.

Three Quick Ways to Improve Your Strategy-Making

The standard strategy processes at most companies share three common characteristics: 1) you wait until the annual strategy review to revisit your strategy; 2) you put together a SWOT analysis as input to the start of the strategy process; and 3) you start the strategy process with a long and arduous exercise to wordsmith a mission/vision statement or organizational aspiration.

These activities are, no doubt, reassuring and familiar. They are also almost completely useless. Let’s take a look at each in turn:

The annual strategy cycle

Last time I checked, competitors don’t wait for your annual strategy cycle to attack, customers don’t wait for your annual strategy cycle to shift their preferences, and new technology doesn’t wait for your annual strategy cycle to leapfrog yours.

Strategy can’t wait for bureaucratic, non-market timing. When you make your strategy choices, you need to specify what aspects of the competitive marketplace — consumer preferences, competitor behavior, your own capabilities — have to remain true for the strategy to be a good one. Then, you need to monitor those religiously.

If those facts about the marketplace don’t change, then revisiting strategy is unnecessary and unhelpful. But as soon as any one of them ceases to hold true, the strategy needs to be revisited and revised. Waiting for a pre-ordained time to do that has only benefits your competitors.

The up-front SWOT analysis

Perhaps the single most common way to kick off a strategy process is with a SWOT analysis. However, there is simply no such thing as a generic strength, weakness, opportunity, or threat.

A strength is a strength only in the context of a particular where-to-play and how-to-win (WTP/HTW) choice, as is the case for any weakness, opportunity and threat. So attempting to analyze these features in advance of a potential WTP/HTW choice is a fool’s game. This is why SWOT analyses tend to be long, involved, and costly, but not compelling or valuable. Think of the last time you got a blinding insight on the business in question from an up-front SWOT analysis. I bet one doesn’t come to mind quickly. The up-front SWOT exercise tends to be an inch deep and a mile wide.

The time to do analyses of the sort that typically turn up in SWOT analyses is after you have reverse-engineered a WTP/HTW possibility. That will enable you to direct the analyses with precision at the real barriers to making a strategy choice — the exploration will then be a mile deep and an inch wide.

Writing a vision or mission statement

Typically right after the SWOT exercise, the strategy team turns its attention to producing a vision or mission statement. This often devolves into a long and arduous process during which the team members argue sincerely about specific word choices in order to produce the “perfect” statement.

Unfortunately, you can’t nail down your vision/mission statement (or what I refer to as your Winning Aspiration) without having made your where-to-play/how-to-win (WTP/HTW) choice. Spending time wordsmithing a vision/mission statement before making a WTP/HTW choice is a colossal waste of time.

That doesn’t mean an aspiration is unhelpful. So, take a quick first pass at a statement before diving into WTP/HTW. But don’t spend more than an hour on it — and then keep revisiting it during and after the making of the WTP/HTW, capabilities, and management systems choices.

If your strategy process is anchored in these three activities, you can expect to see a big improvement if you simply put the cart back behind the horse and lead with some decisions about where to play and how to win.

Strategy making is not about unearthing and implementing a causal chain from the first principles of market conditions and existing capabilities towards the one right market position. It’s about making choices and taking gambles to get where you want to be. Make your strategy process reflect that fact.

May 21, 2014

Will You Be Able to Repay That Student Loan?

This month, thousands of college seniors are tossing their mortarboards in the air – and getting ready to start paying off their student loans.

But will they be able to? A recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by Lance J. Lochner and Alexander Monge-Naranjo takes a closer look at the problem, going beyond simple default rates and looking at repayment patterns, and the total amount owed, more closely. They researched graduates who were not currently making any payments 10 years after finishing school, either because those borrowers were in default or because they had received a forbearance or deferment on their loans. (Deferments and forbearances are more common in the early post-college years, and considered more serious 10 years out.)

One big determinant: how much money you make after you graduate. The researchers found that a $10,000 increase in your post-school salary is equivalent to 1.2% in increased repayment amounts.

It also matters where you went to school. Graduates from four-year colleges tend to repay more of their debts (see the point above about making more money). Two-year colleges and for-profit colleges turn out the most defaulters (and more drop-outs), even though their debts are lower. (Critics of for-profit schools blame the schools for this; the schools themselves say they are simply serving a more financially precarious population, in essence shifting the blame to their students.) Students attending historically black institutions tended to graduate with less-than-average debt, although the researchers warned that the sample size here was too small to draw specific conclusions.

Finally, it also matters how much you borrowed. For every additional $1,000 borrowed, the likelihood of nonpayment rises by 0.4 percentage points. Put differently, to offset every additional $1,000 you borrow, you need to earn an additional $10,000 in income or your risk of nonpayment will rise.

All of these factors are, to some degree, within borrowers’ control – which career path you choose after school, which school you enroll in, and whether you choose a very expensive school or a cheaper option are all up to you, even if which schools accept you, how much financial aid you’re offered, and who ultimately hires you are all outside of your direct control But Lochner and Monge-Naranjo also found a range of factors wildly outside of student borrowers’ control, some of which mattered more than the above. For instance:

Whether your mother went to college. In a regression analysis that controlled for race, SAT score, and parental income, the researchers found that students whose moms didn’t go to college ended up borrowing about $1,500 more, and owed more on those loans 10 years out. However, they note that these borrowers do not have significantly higher default or nonpayment rates than borrowers whose mothers did go to college.

Whether you are a woman or a man. The authors note that women’s “significantly lower post-school earnings” translates into higher nonpayment rates. Women owe more on their loans 10 years after graduating. While men and women have “nearly identical” default rates, according to the paper, “women have defaulted on 80% more debt than have men.” And yet it’s very important to note that once you control for the amount of money men and women make, this gap shrinks and becomes statistically insignificant – confirming that it’s the differential in pay, not some other factor, that leaves women owing more.

Whether you are white, black, Hispanic, or Asian. “On average,” they write, “black borrowers still owe 51% of their student loans 10 years after college, while white borrowers owe only 16%. Hispanics and Asians owe 22% and 24%, respectively.” These are among the most significant findings in the paper, and they’re worth quoting in full:

Among the individual and family background characteristics, only race is consistently important for all measures of repayment/nonpayment. Ten years after graduation, black borrowers owe 22% more on their loans, are 6 (9) percent more likely to be in default (nonpayment), have defaulted on 11% more loans, and are in nonpayment on roughly 16% more of their undergraduate debt compared with white borrowers. These striking differences are largely unaffected by controls for choice of college major, institution, or even student debt levels and post-school earnings. By contrast, the repayment and nonpayment patterns of Hispanics are very similar to those of whites. Asians show high default/nonpayment rates (similar to blacks) but their shares of debt still owed or debt in default/nonpayment are not significantly different from those of whites. This suggests that many Asians who enter default/nonpayment do so after repaying much of their student loan debt.

Importantly, the researchers did control for different college majors, different SAT scores, and different post-school earnings for each racial group. They conclude: “While blacks have significantly higher nonpayment rates than whites, the gaps are not explained by differences in post-school earnings – nor are they explained by choice of major, type of institution, or student debt levels.”

What does explain them? Lochner and Monge-Naranjo don’t have satisfying answers. They speculate that it all comes back to how much money mom and dad have. If your parents can help you out – with both cold, hard cash, and sound financial advice — you’re a lot less likely to end up in nonpayment. The researchers found that every $10,000 increase in parental earnings equated to about $250 less in student loans for their children. And an earlier study by Lochner and colleagues of Canadian students with low post-school earnings found that financial support from their parents was instrumental in keeping students out of default. But one thing that’s not in the data is how much wealth parents have beyond their earnings, which could have important racial implications – previous studies have shown that even when blacks and whites make the same salary, black families still hold less wealth.

With student loan debt at crisis levels, Lochner and Monge-Naranjo’s findings add important nuances. This is information that government leaders and lenders need to pay attention to as the debate over regulation heats up – and that students need before they make possibly the biggest financial decision of their lifetimes.

3 Problems Talking Can’t Solve

Constructive conversations are a vital part of any leader’s job description. But the importance of conversation and communication as a leadership skill is something that can often go unexamined. There is now extensive evidence that shows there is a time and place for conversation — and that any leader or aspiring leader would likely benefit from a more serious consideration of the pitfalls of some types of dialogue. Critically, the nuances that lie within and around conversations are often as important as the conversations themselves.

Let’s look at three situations in which conversations, per se, may not be the answer to effective leadership:

“All talk and no action”: Conversations may create the illusion that something is being done or that one is progressing when all that is being done is communication without the necessary action. This is something we all have experienced and struggle with at work — unaware that there is scientific evidence that helps explain what leaders can do. As early as 2004, Margaret Archer, a well-respected researcher, explored the concept of how one’s actions are impacted by one’s “reflexive” nature. She defined three types of reflexives: “communicative reflexives” are those who require others to complete their internal conversations to enable successful performance; “autonomous reflexives” do the opposite — they shut themselves off from others in the completion of their internal conversations and are much more strategic; and “meta reflexives” are those who use strongly held values to guide their reflexivity. Archer concluded that when you depend on others to help you complete your conversations, you are more likely to remain unmoved within the organizational hierarchy whereas those who rely on their own internal conversations move upward and meta reflexives move laterally within organizations.

While no one style is likely to be exclusively present in any person, this study points to the value of moving in and out of conversation. Specifically, conversation draws our attention outward and creates a feeling of movement, but is often ineffective unless one takes time to translate this experience into an insight and inner conversation that moves one upward within an organization, or when one wants to encourage others to advance as well.

Heightened emotional sensitivity: Although conversations that progress exclusively through mutual understanding and emotional connection can be helpful when forming teams, they can also be very destructive in negotiations particularly. We may be in trouble if all we do is “feel” what another person is saying in order to understand them. A prior series of studies has demonstrated that this type of emotional sensitivity can, in fact, be detrimental to to the outcome of a discussion at the bargaining table. Instead, another form of empathy, cognitive empathy, may be more useful in discovering hidden agreements within the negotiation. This kind of conversation requires using one’s head as well as one’s heart when negotiating. Often, we are content to simply demonstrate that we understand how another person feels, but this is not enough. It pays, in the context of a negotiation, to actually view things from the other person’s point of view so that one can escape one’s own biases.

“Delusional” consensus: Conversations are also often held in order to achieve consensus, but consensus on its own does not imply effective leadership. Humans as a group are prone to multiple illusions, distortions and psychological traps, and having a consensus about these may lead to mass delusion rather than actually effective leadership. One need not even go as far as Hitler or apartheid to make this point. We are all prone to falling into psychological traps, and if we were all prone to these cognitive biases, we might have consensus but be completely wrong.

So what can we do if we are subject to these situations? First, Archer’s research would suggest that all conversation should be followed by internal reflection (see “autonomous reflexives” above) to avoid stagnation. Feed conversational data to yourself consciously and allow your own brain to process this deeply. Secondly, the studies on cognitive empathy suggest that we should not get carried away by sharing emotions during negotiations, but also share points of view. And the fact that we may all fall into psychological traps suggests that decisions need to transcend consensus and may need to be implemented as “best guess” alternatives.

These studies suggest that being an effective leader requires being conversational as well as internal; using your head and your heart; and at times, acting against the consensus of the group. The next time you’re drawn into a conversation, see if you find yourself falling into any of these traps.

The Cable Guys Need to Come up with a Better Argument

A couple weeks ago, at the annual industry hoedown known as The Cable Show, National Cable and Telecommunications Association CEO Michael Powell argued against those who think broadband internet access should be regulated as a public utility:

The intuitive appeal of this argument is understandable, but the potholes visible through your windshield, the shiver you feel in a cold house after a snowstorm knocks out the power, and the water main breaks along your commute should restrain one from embracing the illusory virtues of public-utility regulation.

Powell then went on to contrast these grim images with the shiny world of the internet:

Because the internet is not regulated as a public utility it grows and thrives, watered by private capital and a light regulatory touch.

It’s not too hard to find nits to pick here. Cable internet service goes out in snowstorms, too, and if the latest American Customer Satisfaction Index is to be believed, Americans are much happier with their energy providers (who score a respectable 76 on the index) than their internet providers (a dismal 63, absolute worst of the 43 industries tracked). Potholes are indeed a pain, although unless Powell is proposing to turn every last cul-de-sac in America into a toll road, I’m not clear what his private solution would be. As for the water-main breaks, a lot of them are caused by guys digging up roads to lay cable.

Still, Powell is right that broadband networks are still growing and improving, while the U.S. electricity, transportation, and water networks mostly aren’t. The most obvious explanation for this is that broadband providers are serving a new and burgeoning market. The power, road, and water networks had their boom times, too — and while they are now older, with limited growth prospects, this would also be true if they were unregulated and entirely private. So the question is really whether the current, mostly hands-off regulatory regime for broadband has led to faster growth and more investment than if Powell, as chairman of the FCC, hadn’t decided in 2002 to classify cable broadband as a lightly regulated “information service” instead of a common-carrier “telecommunications service.”

The best answer to this I can come up with is that while I really don’t know the answer, Powell and the cable industry make an awfully weak case for yes. There is economic evidence that some kinds of regulation depress infrastructure investment. If the government is going to restrict how much money you can make, you’ll probably invest less. But since the mid-1990s, telecommunications regulation in the U.S. has been aimed mainly at encouraging competition, not telling providers how much they can charge. For several years starting in 1998, for example, the FCC made the then-dominant providers of broadband service, the phone companies, open their DSL lines to competing internet service providers. The reasoning was that, without regulatory pressure, monopoly owners of communications networks tend to charge too-high prices that depress use of their networks and end up crimping innovation and economic growth. Opening up parts of their infrastructure to upstart competitors was a way to counteract that tendency.

Most other developed countries have continued to force broadband providers to open the “last mile” into consumers’ homes to competitors. Since Powell’s reign at the FCC, the U.S. has instead banked on head-to-head competition between the cable companies and the telcos, each with their own last-mile wires. But cable broadband is markedly superior to DSL, and Verizon’s and AT&T’s plans to wire the nation’s homes with even-faster fiber optic cable haven’t amounted to all that much, at least not yet. So the cable industry has become the dominant provider of wired broadband, and in most of the country competition is muted. Some argue, as Brendan Greeley did in Bloomberg BusinessWeek a few months ago, that the U.S. approach has been shown to be a mistake because the broadband rollout here has lagged that of countries that do have last-mile rules. I’m not entirely convinced by this evidence — international comparisons are difficult, and the race isn’t over yet. But it’s a lot more compelling than the cable industry’s case that we in the U.S. are living in the best of all possible broadband worlds.

The evidence trotted out by the NCTA (the cable lobby) consists mainly of the impressively large quantities of dollars that cable companies have been spending on infrastructure. But as Matthew Yglesias showed last week, that spending appears to have been declining in recent years. In response, the NCTA trotted out a new chart going all the way back to 1990, but even that showed flat spending at best over the past few years.

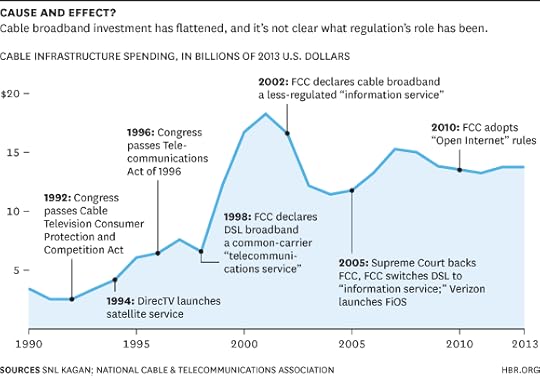

This piqued my interest, and I thought it might be instructive to adjust the numbers for inflation and annotate the resulting chart with a few regulatory and competitive landmarks, to see if any patterns jumped out. I asked the NCTA for the numbers underlying the chart, and was told I should get them from the source: media and communications research firm SNL Kagan. SNL Kagan told me they couldn’t give out “that many data points,” and seemed a little peeved that the NCTA had. So I settled for eyeballing the NCTA’s chart for the numbers, and adjusting them using the GDP deflator for nonresidential fixed investment. Here’s what I came up with:

The main story this chart tells is of a big rise in cable infrastructure spending in the 1990s, then a massive binge during the Internet bubble, then a hangover, and for the past decade a slight upward trajectory with some swings that seem related to the ups and downs of the overall economy.

This doesn’t reflect poorly on the cable guys at all. They’re spending a lot more money than they were in the 1990s, and seem to have gotten past the boom-bust ways of the early Internet to a steady investment plan. But neither does the chart back up any particular argument about the impact of regulation on capital spending. A 1992 cable law that the industry said would depress investment was followed by … a big increase in capital spending. That increase probably had a lot to do with the arrival on the scene in 1994 of satellite television purveyor DirectTV, the first direct competitor most cable companies had faced. The FCC’s 1998 ruling that broadband internet was a common-carrier “telecommunications service” did not visibly discourage spending by cable companies trying to get in on the broadband party. And then, when the FCC decided in 2002 that cable broadband wouldn’t be regulated like that, there was no discernible spending boom — at least not for quite a few years.

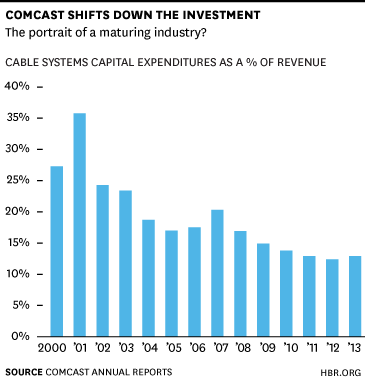

When I looked at a single company, industry leader Comcast, the story was one of a long, steady decline in cable investments as a percentage of cable systems revenue over the past decade and a half (I calculated it that way to reduce distortions from the acquisition of NBC Universal in 2011):

What is Comcast doing with its money instead? It’s been making big acquisitions and giving lots of cash back to shareholders. In 2002, Comcast didn’t spend a penny on share buybacks or dividends; in 2012, buybacks and dividends added up to $4.6 billion, only a little bit less than the $4.9 billion in cable capital expenditures. Last year the company dialed back a bit on buybacks, with just under $4 billion returned to shareholders, but the trend is clearly upward.

This is not a bad thing — it’s what big, maturing companies do. But if Michael Powell wants to keep arguing that his broadband deregulation has unleashed a huge wave of investment and innovation in the U.S., he needs to come up with some better evidence than this.

Where the Jobs Are: Fixing Those Crumbling Roads

With America’s roads, bridges, seaports, and water systems in disrepair and skilled workers heading toward retirement, jobs maintaining the nation’s infrastructure will be wide open in the next decade. The Brookings Institution says nearly a quarter of infrastructure workers will need to be replaced, but beyond that, employment in infrastructure jobs is projected to increase 9.1% from 2012 to 2022. That means an additional 242,000 material movers, 193,000 truck drivers, and 115,000 electricians, Brookings says.

How Boards Can Innovate

Governing boards might seem like the last place for innovation. They are, after all, the company’s steadfast guidance system, charged with keeping an even keel in rough waters. Corporate directors are the flywheel, the keeper of the flame, the preserver of tradition.

All that is true, or least should be so, but companies are also forever having to reinvent themselves — IBM, Nucor, and Wipro bear only the faintest resemblance to their founding forms — and boards ought to be at the forefront of those transformations, not rearguard or resistant. New products are, of course, the province of R&D teams or research partners. But new strategies and structures are squarely in the board’s domain, and we have seen any number of governing boards innovating with, not just monitoring, management.

If boards are viewed as partners with management, not just overseers, innovative ideas are as likely to come from their dozen or so directors — all highly experienced and certainly dedicated to the firm’s prosperity — as any dozen employees of the company. Some boards have taken the principle further by forming their own innovation committee. The directors of Procter & Gamble, for instance, have established an Innovation and Technology committee; the board of specialty-chemical maker Clariant has done the same; and Pfizer has created a Science and Technology committee.

The value of a board’s active engagement in innovation can well be seen at Diebold, a $3 billion-company whose 16,000 employees make ATMs and a host of related products. Founded in 1876, the company had survived far longer than most major manufacturers because of a readiness to embrace new technologies — virtually none of its products today have any resemblance to those of 100 years ago — and its directors hope to ensure that the company incorporates new technologies to survive another 100 years.

To that end, Diebold recruited a new CEO in 2013, Andy W. Mattes, who had previously led major divisions at Hewlett-Packard, Siemens, and other technology-laden companies. And then, in conducting its annual self-evaluation, the board found that a number of its directors had recommended that a board committee be created to work explicitly with the new CEO on technology and innovation — not to manage it, but to partner with management on it. With the concurrence of the new CEO, the directors created a Technology Strategy and Innovation committee with a full-blown charter requiring its directors to “provide management with a sounding-board,” serve as a “source of external perspective,” evaluate “management proposals for strategic technology investments,” and work with management on its “overall technology and innovation strategy.”

The chair of the new three-person committee, Richard L. Crandall — the managing partner of private-equity firm Aspen Partners, who also runs a roundtable for software CEOs and is a former CEO himself — was mindful of the lurking risk that directors might stray into the weeds and step on management prerogatives. He accordingly worked out an explicit understanding among the CEO and his committee members on where the directors should and should not go. “I watch like a hawk,” he said, “to ensure we do not go too far.”

Diebold’s innovation committee members are on call for everything from brainstorming to networking. When Diebold executives began looking for new technologies it might buy, Crandall and his two colleagues — rooted in tech start-up and venture capital communities — helped the CEO and his staff connect with those who would know or own the emergent technologies that could allow Diebold to strengthen its current lines and buy into the right adjacent lines.

Innovations at the top extend even to how the board itself operates, and Blackstone Group — one of the leading investment groups in the world — has been pressing the case. Sandy Ogg, an operating partner in Blackstone’s Private Equity Group, had previously served as a senior vice president for leadership and learning at Motorola and chief human resource officer at Unilever. Having thought a lot about what makes for effective company leadership, whether in the executive ranks or around the board table, Ogg wants to know if the directors of an investment prospect for Blackstone bring a profile that is complementary to their CEO’s, “filling holes that need to be plugged.” He wants to know how prospective directors will react if a CEO tells the directors to get lost. And at companies where Blackstone has invested, Ogg presses directors to “do the work” and not just be a “business tourist.” In other words, Blackstone has been innovatively working to get more out of their boards than traditional norms might have allowed.

Innovative companies that are not innovating in and around the board room run the risk of becoming less so. For example, we are familiar with the boardroom of one of America’s premier technology makers, which is dominated by a non-executive chair who underappreciates how vital but difficult it is to create new products in its recurrently disrupted markets (the innovator’s dilemma). The board has too few technology-savvy directors, and its nomination committee has blocked suggestions for more experienced innovators on the board.

Without innovation at the top in how boards lead, companies may come to see less innovation from below. Viewed affirmatively, directors who learn to work with executives on product and service innovations constitute an invaluable — and free — asset during an era when creativity is increasingly at a premium. And for that, observed David Dorman, former AT&T CEO and now board chair at CVS Caremark Corporation, “we need a robust set of thinkers on the board who know the market place.” With that, the board can take responsibility for ensuring that its enterprise transcends the ever-present dilemma of innovating or dying.

Dennis Carey, Ram Charan, and Michael Useem are offering a two-day program on “Boards That Lead” at Wharton Executive Education on June 16-17, 2014.

More blog posts by Michael Useem, Dennis Carey and Ram Charan

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers