Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1425

May 16, 2014

Help Leaders Be Less Useless at Strategy

At some point in the formulation of a strategy, its creator must review his or her work with the leader, either by choice or by procedure.

If the strategist is a CEO, the reviewer is the board (or a committee thereof). If the strategist is a business unit head, the reviewer is the CEO, and so on down the organization. Regardless of the specific players, the process looks much the same; typically, we wait, and wait, and wait until the strategy feels iron tight. Once it is ready, we go in to the meeting with a perfect slide deck and lots of points in defense of our view.

The goal is to get a big gold star for having produced a wonderful, perfect strategy. Anything less is a disappointment. The creator and the reviewer both know that this is the desired outcome — and they know that the other knows it too. Hence, the creator presents as if everything in the strategy is obviously and unassailably true. And the reviewer most of the time provides the gold star or offers minimal and easily incorporated feedback on small aspects of the strategy. He or she knows that if any criticism is levied or shortcoming pointed out, the creator will be dismayed, if not entirely disillusioned.

This approach to strategy review has the unfortunate effect of rendering the leader in the review position almost useless. If they give the gold star, they have added absolutely nothing of substance to the strategy. And, even if they offer reservations and feedback, the timing of the conversations renders those all but useless too. As W. Edwards Deming taught the production world, inspecting outputs at the end of the production line is the most ineffective way to improve quality.

If these leaders are in their positions legitimately (and if they are not you have a much bigger problem), then strategists should want to use the leader’s judgment and experience to the maximum to improve the strategy. That means going to the leader early and often. Don’t want until your strategy is so polished that you don’t want anything more than a pat on the back. Instead, construct a more productive series of interactions on strategy:

Go early with the framing of the strategy challenge that you want to tackle. Ask your leader whether there is a different way he or she would frame the challenge that you should be working on.

Go back with the possibilities you generate. Ask your leader whether there might be different possibilities he or she would consider or ones on your list that he/she sees as unacceptable on their face.

Return a third time when you have reverse-engineered the possibilities to determine what you believe would have to be true and have identified which of those things that you feel are least likely to hold true. Ask the leader whether there are additional conditions that would have to hold true and about which are they most skeptical.

If you do these things, three great things will happen:

You will get insights along the way that will shape and improve the way you are thinking about the problem at hand;

You won’t be sent back for time-consuming and expensive rework at the end of the process;

You will have a leader who is enthusiastic about the outcome because he or she genuinely helped to shape it.

That is how you transform a leader from being useless to being valuable in creating strategy.

May 15, 2014

Taking Business Back from Wall Street

Gautam Mukunda, HBS professor, on the dangers of managing companies for shareholders. He is the author of the forthcoming article “The Price of Wall Street’s Power.”

Jill Abramson’s Ouster: Why Aren’t Standards This High For Male Leaders?

Jill Abramson is out at The New York Times, and the circumstances of her departure have lots of observers feeling all flavors of depressed, angry, and tired.

We’ve seen this movie before.

It always starts out on a high note (the first woman to be put in charge of an American institution!), but then quickly deteriorates. Throughout her brief tenure, her management style comes under public fire. She’s too brusque. She’s too pushy. She’s too (dare I say it?) bossy. She promotes herself too much, has too many speaking engagements, or isn’t around the office enough. She might even be criticized for her clothes, or her voice. And then, one day, she’s gone.

In the case of Jill Abramson, there is another all-too-familiar twist: reports saying that she was paid less than her male predecessor.

The feminist commentariat has quickly latched on to these details to cry, “Sexism!” Others have been more wary, saying hold on, we don’t know all the details. Maybe she really was an overbearing boss. It’s a tough time to be in journalism – maybe top salaries have to come down.

The skeptics could be right, but that still doesn’t mean her dismissal was unbiased. It would only be free from bias if she were let go the same way a male editor would have been pushed out. Consider: Howell Raines, one of her predecessors, was occasionally critiqued for having a “hard-charging” management style, but he was only chased from the executive editor’s chair following the Jayson Blair plagiarism scandal. He was allowed to resign, and at his send-off, Sulzberger emphasized the decision had been Raines’s, that he had accepted it “sadly,” and that he wanted to “applaud” him for “putting the interests of this newspaper” first.

Again, it’s not biased to fire a woman; it’s biased when a woman is held to a higher standard than a man and is punished differently when she doesn’t meet it. There are a lot of opinionated editors in any newsroom. But are the men allowed to punch walls while the women must hire executive coaches to help smooth their rough edges?

To put it differently: wouldn’t offices everywhere benefit if the male executives were held to the same impossibly high standards as the women?

In 2009, Herminia Ibarra and Otilia Obodaru presented their analysis of 2,816 executives’ 360-degree evaluations: they found that female leaders scored higher than or equal to their male peers on ten out of ten key leadership behaviors. Ten out of ten. This doesn’t mean women are inherently better leaders than men are; it just shows they have to be exceptional to be promoted into positions of leadership at all. And when they do make it to the top of the career ladder, women are more likely to find that ladder leaning against a crumbling edifice. A famous study of FTSE 100 companies by Michelle Ryan and Alex Haslam also showed that women are more likely to be appointed to senior leadership roles when a company is suffering financially – a phenomenon they termed the “glass cliff.”

Why do women have a harder journey to the top and a tougher job when they get there? Joan Williams and Rachel Dempsey offer some answers in their 2014 book, What Works for Women at Work. Consider what they call the “Prove-It-Again! bias.” Citing study after study, they document how women’s mistakes are judged more harshly, and remembered longer, than men’s. When women are successful, it’s more likely to be ascribed to luck; when men succeed, though, it’s noted as skill. Men are also more likely to be judged on their potential, while women are held accountable for having actual accomplishments. In the hiring and promotion process, standards that are relaxed for men are tightened for women. Over two-thirds of the female leaders in Williams and Dempsey’s study reported encountering some form of Prove-It-Again! bias.

Or think about another form of bias the authors call the Tightrope. It’s been well documented that for men, success and likability go hand-in-hand, while for female leaders, there’s a tradeoff. Here’s how Williams describes it: “All high-paying jobs are traditionally seen as requiring masculine qualities, while women are expected to be feminine. So women in these jobs often find themselves walking a tightrope between being seen as too masculine – respected but not liked – and being seen as too feminine – liked but not respected. ” Nearly three-quarters of the women in her study reported this type of bias.

Williams also found that the Tightrope became even more difficult to navigate as the woman continued to climb higher in the organization. Instead of getting to the top role and finding that they’d finally “made it,” the women in her study reported that the scrutiny only got worse. To deal with it, the more hard-charging female executives had to develop intentionally compassionate, consensus-driven leadership styles – ones that wouldn’t conflict with the stereotype of how a woman is supposed to be.

While it’s easy to lament that this isn’t fair – women should be allowed to be just as brusque and bottom-line focused as men, dammit! – what we should really be arguing for is the reverse: more humane workplaces where male bosses, too, have to occasionally remember to ask how their employees are feeling.

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Let’s say you’re working in a new market, far away from headquarters, and you need to get approval for an initiative that is somewhat outside the company’s current strategy. What do you do?

A case study we just published on Samsung’s European innovation team offers some helpful insights. It details how in 2010, Samsung set up a small consumer-focused innovation team in London, headed by Luke Mansfield. The team’s mission was to come up with new products for the European market — and then, significantly, to convince senior management in South Korea to invest in those projects — several of which, it turned out, required Samsung to deviate from their current strategy within the product categories in question.

After more than three years of operation, it was clear that the team had worked out how to do this: by late 2013, the total measurable profit contribution from their projects was expected to hit half a billion dollars. As we spoke to them, Mansfield and his team shared five insights on how to work with senior management to get strategy-stretching innovations to market:

1. Negotiate the expectations up front. Everyone realizes that a new market will often require deviations from the existing strategy. So have a conversation with your managers about how to handle these types of conflicts and negotiate increased autonomy for your team so you get some wiggle room on results.

Mansfield made it a precondition of accepting the job that he got a three-year grace period before he was required to deliver results. As he told us, “Getting the agreement in place didn’t prevent management from asking questions, but it did allow us to push back and tell them ‘no’ at times.”

2. Build trust with low-risk ideas. As Mansfield’s colleague Ran Merkazy put it, “When we hire people, we explicitly tell them that their job is not to push for disruptive ideas at Samsung. Rather, it is to position themselves to create disruptive innovation. Before they can do anything, they need to move the needle on the trust gauge, making other people in the organization believe in them.”

In one case, the team managed to deliver a new, low-risk project to a senior manager in Korea just when he needed to present new ideas to his boss. He was eventually promoted, and became a useful resource for the team in their work to get more ambitious projects approved. Merkazy added, “Having built that initial trust means that once or twice a year if we run into resistance with a disruptive idea, we can bypass the middle levels and talk directly to the senior executives in the division. [But] you need to be very cautious about using that connection; bypass middle management too often and you risk turning them into enemies.”

3. Present a portfolio of options. Team member Jerome Wouters explained: “If we present five concepts, we will make sure two of them will be low risk and more incremental, two will be a bit more ambitious and only the final one will be a high-risk/high-reward concept — but with some elements that will be doable in the short run, which makes the whole concept less crazy. That way, our stakeholders can select how much risk they are willing to take for their business given their current circumstances, instead of making it a go/no-go decision on specific ideas.”

4. Manage the choice of evaluation methodology. Many large companies use established frameworks to assess new ideas, and by nature, methodologies favor specific types of ideas over others. To get ideas past the approvals gauntlet, it is crucial to have a detailed understanding of how the test works.

Mansfield’s team arrived at that insight after one of their earliest and most ambitious ideas (for a new kind of fridge) was rejected by headquarters. One issue was that Samsung used a specific quantitative survey methodology that, while good for assessing incremental products, was arguably biased against more radical ideas, such as the new fridge. Following that setback, the team took an unusual step: they developed their own evaluation methodology, and convinced senior management to use it alongside the standard one.

5. Consider going under the radar. Sometimes, it is better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission — and in one case, the team deliberately decided to ignore the corporate rules.

They had identified a problem with the Galaxy phone brand: If you switched to the Galaxy S2, it was difficult to import your contacts, photos and other data from your old (non-Samsung) phone. So they built an app called EasyPhoneSync that solved the problem, and got ready to launch it — only to be told to drop the project, as a team in Korea was working on a similar solution.

Mansfield’s team understood that some projects would be killed, and normally would have followed the order. But it was unclear when the other app would be released, and the team knew that the timing was crucial: the Samsung Galaxy S3 was about to be launched, and the lack of a good solution could cost Samsung lots of new customers. So they decided to take a risk and proceed with the launch of their own app.

It proved immediately popular, and by the end of 2013, it had been downloaded over a million times. As we have written elsewhere: If other options are closed to you, sometimes a bit of judiciously applied corporate disobedience can be the right way to go.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Should Big Companies Give Up on Innovation?

How GE Applies Lean Startup Practices

That Mad Men Computer, Explained by HBR in 1969

It’s 1969 on this season’s Mad Men, and a glass-enclosed climate-controlled room is being built to house Sterling Cooper’s first computer — a soon-to-be-iconic IBM System/360 – in the space where the copywriters used to meet.

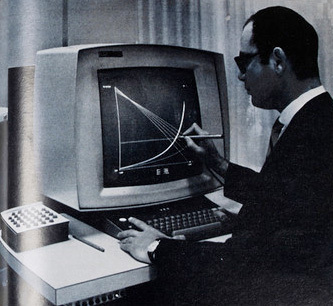

That same year, in an article entitled “Computer Graphics for Decision Making,” IBM engineer Irvin Miller introduced HBR’s readers to a potent new computing technology that was part of the 360 — the interactive graphical display terminal.

Punch cards and tapes were being replaced by virtual data displays on glass-screened teletypes, but those devices still displayed mainly text. Now the convergence of long-standing cathode-ray-tube and light-pen hardware with software that would accept English language commands was about to create a revolution in data analysis.

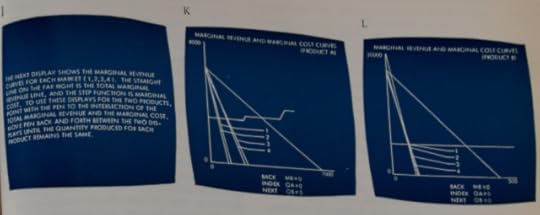

Previously, if executives had wanted to investigate, say, the relationship of plant capacity to the cost of production, marginal costs to quantity produced, or marginal revenues to quantities sold, they’d have to fill out a requisition, wait for a data analyst to run a query through the machine, using some computer language like Fortran, and then generate a written report. That could take months.

But interactive graphics offered the possibility of providing realistic answers quickly and directly. As Miller explains: “With such a console in his office, an executive can call for the curves that he needs on the screen; then, by touching the screen with the light pen, he can order the computer to calculate new values and redraw the graphs, which it does almost instantaneously.”

To read Miller’s tutorial is to return to some first principles that may still be worth bearing in mind, even in today’s world of vastly greater amounts of data and computing power (the largest mainframe Miller refers to has a capacity of two megabytes). The first is his almost off-hand initial stipulation that the factors affecting a business that a computer can process are quantitative.

The second is his explanation (or, for us, reminder) of what the computer does when it delivers up the graphs: “To solve business problems requiring executive decisions, one must define the total problem and then assign a mathematical equation to each aspect of the problem. A composite of all equations yields a mathematical model representing the problem confronting the executive.” Miller suggests, as an example, that a system programmed with data on quantities produced and sold, plant capacity, marginal cost, marginal revenues, total cost, total revenue, price, price for renting, and price for selling could enable businesspeople to make informed decisions about whether to hold inventory; expand plant production; rent, buy, or borrow; increase production; and examine the effects of anomalies on demand or the effects of constraints.

Even in this simple example it’s easy to see how hard it is to “define the total problem” — how, for instance, decisions might be skewed by the absence of, say, information on interest rates (which in 1969 were on the threshold of skyrocketing to epic proportions) or of any data on competitors, or on substitutes (a concept Michael Porter wouldn’t introduce until 1979).

Miller is hardly oblivious to the dangers (the term “garbage in; garbage out” had been coined in 1963); and in answer to the question of why an executive should rely on the differential calculus and linear programming that underpins the models (interestingly, Miller assumes senior business executives haven’t had calculus), he replies that the point of the equations is only to “anticipate and verify intuitive guesses which are expected to be forthcoming from the businessman” [italics original]. In other words, the mathematics are essentially meant to serve as an amplification of the executive’s judgment, not as a substitute.

Intuition-support is, in fact, the point for Miller. For him, the real benefit of the new technology isn’t just the ability to perform what-if analyses on current data, as powerful as that is, but that executives could do it in the privacy of their own offices, which would afford them the time for the private reflection from which intuition springs. “The executive needs a quiet method whereby he alone can anticipate, develop, and test the consequences of following various of his intuitive hunches before publicly committing himself to a course of action,” Miller says, before he even begins to explain how the technology works.

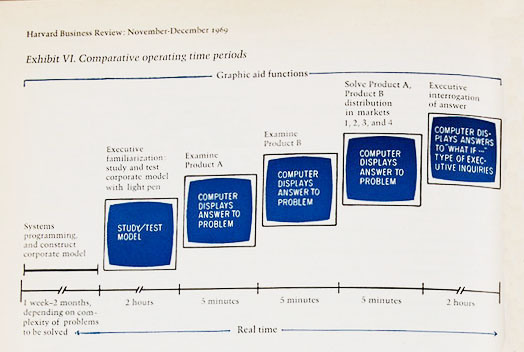

In this it’s enlightening to revisit Miller’s estimates of how much time the entire process was supposed to take: a few weeks to construct the model, five minutes to conduct each what-if scenario – and then two full hours for the executive to consider the implications of the answers. In this, HBR’s first examination of data visualization, it is in those two hours of solitary quiet time that the real value of interactive computing lies.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

Who’s Responsible for the Walmart Mexico Scandal?

The Walmart bribery scandal is one of the most closely-watched cases of alleged malfeasance by a global company. It broke into the open in April, 2012, when the New York Times published a lengthy investigative piece alleging Walmart bribery in a Mexican subsidiary and a cover-up in its Bentonville, Arkansas, global headquarters. The piece, which won a Pulitzer Prize for reporter David Barstow, raised a host of personal accountability and corporate governance issues for the company.

Late last month, on the second anniversary of the story nearly to the day, Walmart released its first Global Compliance Report (GCR). The report describes the company’s governance response and changed compliance framework — from holding 20 audit committee meetings in 2014, to substantial organizational restructuring, to enhanced education and training. On paper, Walmart appears to have adopted many best practices and to have set out a sound plan for moving forward. However, questions of accountability remain unanswered, when it comes to determining what actually happened in the past, what systems failed, and who was responsible for possible violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which bars bribery of foreign officials. A lengthy internal inquiry continues, as well as investigations by the Justice Department and the SEC, with the scope broadened to include possible Walmart improprieties in Brazil, China and India.

Finding the answers to these questions is important in two ways. First, the answers will determine whether current and past senior officials are culpable and whether any sanctions (governmental or company imposed) are appropriate. Holding people accountable — especially senior officers — is essential to deterrence inside Walmart (and for other companies, too). The essence of the Times story was the allegation that Walmart Mexico, under the direction of the then country CEO and his General Counsel, bribed officials to get permits and clearances for new stores — and falsified records of these transactions. When a Walmart lawyer in Mexico blew the whistle in 2005, senior officers both in Mexico and in the United States allegedly stopped two different efforts by other Walmart employees at headquarters to conduct a thorough and independent inquiry. The whistleblower charges were sent back to Mexico and buried. Although it must be emphasized that there are no official findings as yet, these senior officers, according to the story, included the then-Walmart CEO and General Counsel in Mexico, the then-CEO, Lee Scott (recently retired as member of the Walmart board); the then-head of Walmart international, Mike Duke (who succeeded Scott as CEO, has just retired from that position, and remains on the Walmart board as executive committee chair), and Thomas Mars, then-General Counsel. Also at issue are what and when management told the board and what processes the board had for oversight.

Second, the reforms outlined in the GCR are hard to evaluate fully unless and until the specific problems that prompted them are laid out in detail. Certainly an important goal for Walmart’s board and current management is to improve the company’s compliance capability. But it is also likely that enhanced compliance personnel, processes and systems are part of a company effort to respond to problems uncovered in the investigation to improve its position in settlement negotiations with the government. Whether there will be a settlement, what facts Walmart will admit and what precise sanctions and future obligations it will face are not known to outsiders at present.

What is known is that the inquiry is wide-ranging and Walmart has taken it very seriously. Through January, 2014, the company has spent $439 million on the probe, and estimated that it would spend $200-240 million more on investigative and compliance costs this year. It has retained three law firms, one for the audit committee, one to conduct an internal investigation and one to advise on the global compliance review. Moreover, it is paying numerous other firms to represent 30 Walmart employees who have been questioned in the probe, including senior executives from corporate headquarters.

The Global Compliance Report does respond, in general, to issues raised in the original story. Most substantially:

Walmart has a number of initiatives to combat the culture of silence which allegedly allowed the Mexican scandal to fester for a number of years before corporate leadership was informed. That malign culture, in turn, allowed corporate leadership to ignore the evidence of wrongdoing and keep the board in the dark. Among the most important new initiatives is an escalation and review procedure which aims to ensure that high-risk issues move swiftly to the attention of the chief ethics office in headquarters, which has a direct link to the Audit Committee. (Think GM and its delays in addressing problems with an ignition switch.)

Walmart has made a number of organizational changes to integrate compliance, legal, risk and finance staffs, both in geographies and in relation to different compliance subjects. This step aims to bring appropriate expertise (e.g. anti-bribery, money laundering, product safety, etc.) to different types of compliance issues in different nations and markets, and to create checks and balances so that key staff functions can be both partners to business leaders as well as guardians of the company, and not be pressured by business leaders to ignore serious issues. In the report’s next iteration, Walmart should, however, explain more clearly how its newly drawn (and perhaps overly complex) matrix organization will actually carry out the fundamental compliance tasks of prevent, detect and respond — how it will map business processes, assess risks under various requirements, prioritize them and then mitigate them.

Walmart has instituted a critical technique for ensuring board and senior management involvement in creating a culture of integrity. The Audit Committee on behalf of the board sets key compliance objectives for the next calendar year. The Committee then assesses whether senior managers have met those objectives. If not, then some or all of that executive’s cash incentive will be withheld by the board’s Compensation Committee. This vital focus on pay for performance with integrity involves the board and senior management in articulation and implementation of key annual compliance goals, just like key annual commercial goals. Here, too, more detail is needed in the next Compliance Report about what the goals actually are (one can infer them from the Report but a clear articulation would be more potent) and what methods were used to measure whether or not the goals were met.

What is missing, in my view, is a powerful statement by the CEO that he is the leader of compliance in Walmart — and a companion, deeply-felt statement by the board that this is a core CEO responsibility. The Report is replete with redrawn organizational boxes and organizational detail. But, an integrity culture is simply not possible without CEO commitment to integrity as a bed-rock company goal, and to driving compliance deep into the organization through personal action and reviews. In both the current Annual Report and Proxy Statement, there are rather pro forma statements, but not a sense of real personal commitment from the CEO (as opposed to the Audit Committee) or the board. Similarly, the company must make clear the related point that the top operating business leaders are the chief integrity and compliance leaders in their sphere — that they must make this issue a reality by their own personal actions and leadership.

Walmart’s bribery scandal, and the sweep of the current investigation, have made this case a poster-child for the snares of corruption facing global companies, putting it in the same category as the towering bribery scandal faced several years ago by Siemens. Many boards and CEOs from around the globe cite corruption as one of the top issues they face in current globalization efforts — in this sense, “the whole world is watching” the Walmart case carefully.

With its Global Compliance Report, Walmart has written an important chapter in this saga. But, until the results of the investigation are made public and the government’s response revealed, the story — both on past accountability and future governance — is far from over.

Build Your Own All-Star Team

Let’s imagine that you have recently assessed your company’s talent, and that you found plenty of high-performing executives and employees. Yet somehow your company’s overall performance isn’t where it should be — all those “A” players just aren’t getting the job done. Why?

The fact is, it isn’t enough just to hire the best. If you want to boost the productivity of your organization’s human capital, you also have to deploy those high performers effectively — put them to work so they can deliver the results they’re capable of. One of the most effective methods of deployment I’ve seen is to create all-star teams. Teams like these are a kind of force multiplier: if you group (say) three individuals from your list of A players into a team, you’ll typically get more than three times the output.

High-performing teams are the secret behind many extraordinary accomplishments. In the 1990s, for instance, then-CEO Mickey Drexler turned Gap around by creating a team of A-list merchants and designers, including luminaries such as Maureen Chiquet, now CEO at Chanel, and Andy Janowski, who later became CEO of Smythson. The team transformed Gap’s products and stores and helped the company grow faster than any other retail brand at the time.

More recently, SpaceX, the rocketry and spacecraft company founded by legendary entrepreneur Elon Musk, developed its Falcon 9 launch vehicle for just over $300 million. A NASA analysis determined that the space agency would have had to spend nearly $1.4 billion to achieve the same result. One big difference according to NASA: SpaceX relied on many fewer people. Its engineers worked long hours, probably longer than their NASA counterparts would have. But even more important was the efficiency and productivity of SpaceX’s top-performing design teams, which developed and launched the rocket for a fraction of what it would have cost NASA.

Many companies fail to take advantage of the force multiplier because their organizational systems get in the way. Here are three tips that may help you get past those internal obstacles:

Rank and reward team performance, not individual performance. Some companies rate individuals against each other and give disproportionate rewards to the top performers. These “stacked ranking” systems may sound appealing, but they work against high-performance teams. When there’s stacked ranking, people who are A players typically decline to collaborate with other top performers, for fear their ranking and incentive compensation will suffer. You’ll escape this trap if you reward team rather than individual results.

Create an inspiring goal. You can’t put your top-performing teams on every job — there aren’t enough A players to go around. So save these teams for the mission-critical tasks, and make sure every member understands the tasks’ importance. Teams of Navy SEALS and the best NASCAR pit crews succeed because every team member is a high performer and because they all know that achieving their goal matters. The teams at Gap and SpaceX were doing jobs that would determine the future of the company. If you want your top performers to work productively together and forget about their sometimes-large egos, you have to inspire them to put the mission first.

Put top leaders in charge of top teams. A 2012 academic study of a large company’s front-line supervisors concluded that, as one summary put it, “The most efficient structure is to assign the best workers to the best bosses.” Great bosses bring out the best in people by getting them to work more effectively. Think of Ford Motor Co. over the past 20 years: until 2006, its finances were shaky, and it was losing about a point of market share every year. Then Alan Mulally became CEO, and only a few years later Ford was making money and gaining share. Yet Mulally’s senior team is mostly the same group of individuals who were there while Ford was struggling. The difference was leadership.

The force multiplier from effective teaming and deployment is powerful: companies that tap into it can expect to improve their human capital productivity significantly. Like Ford, Gap, and SpaceX, they can perform better than anyone could reasonably have expected.

The IT Project That Brought a Bank to Its Knees

Sir Christopher Kelly, a former British senior civil servant, recently produced a damning report, which reviewed the events that led to the £1.5 billion capital shortfall announced by the U.K.’s Co-operative Bank in June 2013. This shortfall resulted in its parent, Co-operative Group, ceding control of the bank to bondholders, including U.S. hedge funds. One section highlights the problems the bank encountered as it attempted to replace its core banking systems, a program that was cancelled in 2013 at a cost of almost £300 million.

“The weight of evidence supports a conclusion that the program was not set up to succeed,” Sir Christopher writes. “It was beset by destabilizing changes to leadership, a lack of appropriate capability, poor coordination, over-complexity, underdeveloped plans in continual flux, and poor budgeting. It is not easy to believe that the program was in a position to deliver successfully.”

The factors contributing to the failure cited in the report are ones that we all too frequently have encountered when we have reviewed challenged or failed projects. We have developed a simple yet powerful framework that leadership teams can use to navigate the digital landscape and avoid the kinds of problems that Co-operative Bank suffered. It is based on four questions.

1. Are we doing the right things?

This is the strategic question. The CEO’s first accountability is to clearly and regularly communicate what constitutes value for the enterprise and the strategic objectives to which all investments must contribute and against which their performance will be measured. The second is ensuring through the initial investment-selection process and regular portfolio reviews that resources are allocated to investments that are both aligned with and have the greatest potential to contribute to the strategic objectives.

While the strategic rationale for the Co-operative Bank’s investment was not in question, the Kelly report notes that the bank’s leadership “was over-estimating its capability to deliver such a complex program.” For one thing, an investment of such complexity and risk had not been successfully undertaken by any U.K. full-service bank and, with limited exceptions, major banks in Europe and North America. Evaluating such risks is a key consideration in assessing any IT investment, especially one that is part of a major transformation. Two key questions are: Do we understand the extent of change required for this investment to succeed? And is this level of change achievable?

2. Are we doing them the right way?

This is the architecture question. Because this question is usually thought of as relating to technical architecture, it is generally considered by CEOs as a technical issue and the domain of the CIO. Nothing could be further from the truth. What we are advocating here is a broader view of architecture − enterprise architecture − that has both organizational and technological components. The CEO is accountable for ensuring that there is an overall enterprise architecture.

Since the Kelly report doesn’t consider this issue, we cannot comment specifically about whether the bank’s leadership gave adequate consideration to the standardization of processes and the degree of integration across all businesses. However, the observations in the report suggest that if such consideration had been given, it may have raised a number of flags.

3. Are we getting them done well?

This is the delivery question. Although this is the area where there is a significant body of knowledge, it is the one where the failure of governance continues to result in significant and very visible failures. We continually find that most major transformation initiatives end up being managed as IT projects, with responsibility abdicated to the CIO.

This is clearly where the Co-operative Bank’s program floundered. As the Kelly report states, “the Bank neither had the requisite levels of discipline before the program began, nor built it during the program.” Communication and coordination between different parts of the business involved in the program were weak. Dysfunctional and unconstructive working relationships across these areas did not help matters. There was also a lack of clarity about responsibilities for deliverables: People interviewed for the the report described “managers managing managers, managing managers.” A board subcommittee was supposed to provide closer oversight of the transformation program, but Sir Christopher says the figures were neither analyzed in sufficient detail nor with sufficient consistency to give it insight into key drivers of cost escalations. The message consistently given to the sub-committee by the program’s managers was the initiative was making satisfactory progress even when this was not the case.

4. Are we getting the benefits?

This is the value question. Surprisingly, this is the question that receives the least attention in most enterprises: Few measure or assess whether expected benefits have been delivered. This question also cannot be delegated to the CIO. In ensuring that expected benefits are realized and sustained, the CEO must be the person accountable for maximizing value from the portfolio of business-change investments. The Kelly report notes that there was a failure to develop a detailed business case and a complete lack of consistency about the expected benefits across the program.

Addressing these four basic questions is not just something to be done on a one-time basis to secure funding for any proposed investment. They must all be considered both individually and collectively on an ongoing basis to ensure that value is realized from investments in IT-enabled change. CEOs and boards may balk at this, but they need to recognize that IT is increasingly embedded in all aspects of their business, and creating and sustaining value from the change that IT both shapes and enables falls within their realm of accountabilities. The consequences of failing to do so are starkly illustrated by the Co-operative Bank’s crisis.

May 14, 2014

Alibaba Looks More Like GE than Google

Alibaba, the Chinese internet titan that filed for an IPO in the U.S. last week, could be the largest tech IPO in history. But Alibaba doesn’t look much like Facebook, Google, or even Amazon. Instead, it operates more like GE.

Spanning e-commerce, payments, messaging, business software, entertainment, and more, Alibaba looks a lot like a conglomerate. And it sets strategy like one, according to a Harvard Business School case study by professor Julie Wulf. Competition trumps cooperation, and distributed decision-making by individual business units trumps universal strategy.

With its success, Alibaba and its founder Jack Ma are making the case for a strategy approach that has fallen out of favor in the U.S. As the 2010 case describes:

By his own admission, Ma was a fan of Jack Welch, so it was only natural that his organization came to resemble that of GE in some regards. Just as Welch did not dictate an overall theme or strategy for GE, Ma preferred not to set one agenda from Alibaba’s corporate center, but rather to have each subsidiary set its own strategy. Much like Welch’s famed “#1 or #2” objective for each of this businesses, Alibaba’s governance inspired its subsidiaries to be the leaders of their respective industries. Ma explained, “Business unit presidents must have the freedom to do what is right for their business. I want business units to compete with each other…and focus on being the best in their businesses.

While conglomerates are few and far between in the West, their success in China is no surprise. As a 2013 HBR article explained, “Conglomerates may be regarded as dinosaurs in the developed world, but in emerging markets, diversified business groups continue to thrive.”

The article, by J. Ramachandran, K.S. Manikandan, and Anirvan Pant of the Indian Institute of Management at Bangalore, Tiruchirappalli, and Calcutta, respectively, also offers a concise history of the rise and fall of Western conglomerates:

Conglomerates were all the rage in the United States and Europe for decades, but hardly two dozen of them survive there today. By the early 1980s, they had been laid low by their poor performance, which led to the idea that focused enterprises were better at creating shareholder value than diversified companies were. Most conglomerates shrank into smaller, more specialized entities.

The heart of modern strategy is the alignment of complementary activities. If activities are complementary, they should be combined as divisions of the same firm, the thinking goes. If they are not complementary, part of the firm should be sold. Conglomerates resist this approach, combining more diverse businesses and allowing them separate decision-making structures. Investors are wary of this approach. As the article authors write, “On Wall Street the typical conglomerate discount ranges from 6% to 12%.”

Alibaba’s businesses are not completely diverse, of course. There is a central theme behind them all, and it is the rise of internet usage in China.

What stands out in the Alibaba case isn’t a total rejection of complementarity, but an approach to strategy that mirrors that of conglomerates. Rather than dictating decisions from the top down, Alibaba lets them roll up from the individual businesses. “When internal competitive conflicts arose among Alibaba’s businesses, the firm’s culture tended to favor individual subsidiaries over the group,” according to the case. “Ma constantly made subsidiary heads aware they had the freedom to do what was right for their businesses.”

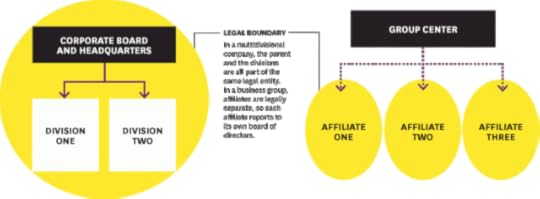

Like conglomerates, Alibaba’s businesses have separate boards, and even separate technology teams and platforms. The exhibit below, from the 2013 HBR piece, describes how Alibaba and firms like it handle strategy, in light of such a distributed approach: with a “group center.”

A “group center” is a group of executives in a conglomerate tasked with long term strategy, locating cross-business opportunities, and shaping the firm’s identity and values. Sure enough, this resembles how Alibaba is organized. One-hundred and twenty executives from its subsidiaries and C-suite form what is known as the “Group Organization,” a leadership team that meets annually to set long-term strategy and to consider “complementary organizational changes.”

Some group centers emphasize strategy work over identity or vice versa, but the authors suggest that the most successful ones balance the two.

This group-led approach to conglomerate strategy offers key advantages, the authors argue, in balancing the search for cross-business opportunity with a more flexible structure for day-to-day management solutions. They write:

In a sense, the business group liberates strategy from structure. Though structure is supposed to follow strategy, the former’s limitations seem to have decided strategy until now. Too often the need to pass up opportunities in order to satisfy shareholders’ expectations has inhibited companies’ growth. A business group, particularly one led by a dynamic group center, enables the pursuit of shareholder value at the affiliate level as well as strategic value at the group level. That makes the business group a winning organizational structure even if it isn’t popular in North America — yet.

While conglomerates may not be about to catch on in the U.S., there are signs that their bottom-up approach to strategy might be making a comeback. Facebook is unbundling its services, giving up on offering a single, comprehensive online offering and instead offering a series of separate apps. At some point, the company will have to decide whether the strategy flows up from those divisions, or flows down from the top — and what to do when two groups’ interests conflict.

The justification for the move, according to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, is the “premium on creating single-purpose, first-class experiences.” Jack Ma would no doubt agree.

Decisions Don’t Start with Data

I recently worked with an executive keen to persuade his colleagues that their company should drop a long-time vendor in favor of a new one. He knew that members of the executive team opposed the idea (in part because of their well-established relationships with the vendor) but he didn’t want to confront them directly, so he put together a PowerPoint presentation full of stats and charts showing the cost savings that might be achieved by the change.

He hoped the data would speak for itself.

But it didn’t.

The team stopped listening about a third of the way through the presentation. Why? It was good data. The executive was right. But, even in business meetings, numbers don’t ever speak for themselves.

To influence human decision making, you have to get to the place where decisions are really made — in the unconscious mind, where emotions rule, and data is mostly absent. Yes, even the most savvy executives begin to make choices this way. They get an intent, or a desire, or a want in their unconscious minds, then decide to pursue it and act on that decision. Only after that do they become consciously aware of what they’ve decided and start to justify it with rational argument. In fact, recent research from Carnegie-Mellon University indicates that our unconscious minds actually make better decisions when left alone to deal with complex issues.

Data is helpful as supporting material, of course. But, because it spurs thinking in the conscious mind, it must be used with care. Effective persuasion starts not with numbers, but with stories that have emotional power because that’s the best way to tap into unconscious decision making. We decide to invest in a new company or business line not because the financial model shows it will succeed but because we’re drawn to the story told by the people pitching it. We buy goods and services because we believe the stories marketers build around them: “A diamond is forever” (De Beers), “Real Beauty” (Dove), “Think different” (Apple), “Just do it” (Nike). We take jobs not only for the pay and benefits but also for the self-advancement story we’re told, and tell ourselves, about working at the new place.

Sometimes we describe this as having a good “gut feeling.” What that really means is that we’ve already unconsciously decided to go forward, based on desire, and our conscious mind is seeking some rationale for that otherwise invisible decision.

I advised the executive to scrap his PowerPoint and tell a story about the opportunities for future growth with the new vendor, reframing and trumping the loyalty story the opposition camp was going to tell. And so, in his next attempt, rather than just presenting data, he told his colleagues that they should all be striving toward a new vision for the company, no longer held back by a tether to the past. He began with an alluring description of the future state — improved margins, a cooler, higher-tech product line, and excited customers — then asked his audience to move forward with him to reach that goal. It was a quest story, and it worked.

Good stories — with a few key facts woven in — are what attach emotions to your argument, prompt people into unconscious decision making, and ultimately move them to action.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers