Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1427

May 13, 2014

Will China Bring Your Firm New Owners, Partners, or Competitors?

Consumers in the United States are used to buying products that are made in China. American multinational firms are accustomed to selling to Chinese customers within China. But what happens when China goes West? What are the implications for corporate America when Chinese firms begin doing business in the U.S. and other developed markets?

You may think this is an issue for tomorrow—when Chinese firms are known for being innovators instead of imitators, and when their overseas investments are not limited to natural resources in Africa and Latin America. But Chinese companies of all sizes are already operating in the U.S. in a big way. More than 80% of last year’s special U.S. visas for immigrant entrepreneurs were issued to individuals from China. U.S. corporations are placing orders for Lenovo-made laptops, while American workers are driving cars made by Chinese-owned Volvo to the office and feeding their families bacon produced by Shuanghui International, the new owner of Virginia-based Smithfield Foods. In total, Chinese companies invested $90.2 billion internationally last year, according to official Ministry of Commerce statistics.

The rise of Chinese investments in the U.S. offers very tangible benefits for the U.S. economy, but it is also changing the traditional dynamics of our domestic competitive landscape. How should corporate America respond? The answer to this question varies depending on whether an American firm is considering new ownership, seeking new partners, or responding to new competitors from China.

For American companies seeking strategic investment, Chinese ownership presents a new alternative to the traditional routes of private equity investment or acquisition by a larger domestic industry incumbent. A top concern among firms taking on private equity investment is who becomes the ultimate decision maker. Under private equity investment, the CEO—formerly the top decision maker in the company—has to answer to the representative assigned by the private equity firm. Chinese ownership can remove this concern from the equation. Moreover, Chinese owners may even be in a position to inject additional capital into a firm after a first round of investment, which would be almost unheard-of under private equity ownership.

During the global financial crisis, Robert Remenar, CEO of Nexteer, a Michigan-based automotive steering firm, deliberately searched for potential new Chinese owners. His firm required significant capital investment, but he knew that the fundamentals of Nexteer’s business were working well. In 2010, Chinese firm AVIC Automotive purchased Nexteer for $465 million. Under the new ownership, Remenar retained his entire management team and was allowed decision-making authority from the new owners to implement an effective strategy to get the firm back on track.

For American firms partnering with Chinese companies, access to new international markets, especially in China, is an obvious gain. In theory, this might sound like an ideal relationship: the American partner possesses technical know-how or a world-class brand while the Chinese partner brings capital and new market access. But what are the broader implications for industry standards? Western companies should consider the long-term implications of partnerships with Chinese firms, in particular the issues of intellectual property and technology transfer.

To cite just one prominent example, Hollywood studios and directors are now forming partnerships with Chinese production houses at a rapid pace—from DreamWorks Animation to Titanic director James Cameron. As collaboration between Hollywood and Chinese firms deepens over time, it will be interesting to see the impact these partnerships have on the Chinese movie production industry. Will Chinese production houses be able to close the knowledge gap and begin producing international blockbuster films of their own? Or will they remain reliant on experienced Hollywood experts for the long term?

Finally, a common misconception of Chinese investment in the U.S. is that the poor product quality, food safety issues, or corrupt business practices that may be present in firms’ China operations will carry over. This assumption is false. When a Chinese company operates in the U.S., it must do so in accordance with local regulations and business practices—or else face the legal consequences. For example, Sinovel, a Chinese wind turbine producer, had to divest its U.S. operations last July after it was charged in federal court with stealing trade secrets from its former U.S. supplier.

However, there may be cases when Chinese firms receive special incentives from the Chinese government (particularly state-owned enterprises), which could enable them to compete at unfair price points or extend contract terms to their customers at less than market value. In the U.S., the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission are both involved in the deal review process to monitor such anti-competitive concerns. American firms operating in the same industry as Chinese competitors should remain vigilant and work together to lobby relevant regulators and government bodies to prevent any anti-competitive business practices from taking place.

We are still at the beginning of the phenomenon of China going West. The number of Chinese companies operating in the U.S. as well as the amounts of their investments will continue to increase dramatically in the months and years ahead. Understanding what this means for American business is critical to ensure U.S. firms and the public can capitalize on new opportunities while avoiding or minimizing potential business risks.

May 12, 2014

Understanding the New Battle Over Net Neutrality

The Federal Communications Commission is expected to issue new proposed rules this week on “network neutrality,” the principle that broadband Internet service providers can’t discriminate among the content that runs through their pipes. Early indications are that it will be an Animal Farm sort of net neutrality, with some nets more neutral than others. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler promised recently that his agency “will not allow some companies to force Internet users into a slow lane so that others with special privileges can have superior service.” But the rule seems likely to allow ISPs to cut deals with content companies to ensure that their packets get delivered smoothly — as Netflix reluctantly agreed to with Comcast in February and Verizon last week. Which by definition means they’re in a faster lane than others, doesn’t it?

At this point, you may be expecting me to launch into a thundering denunciation of this assault upon our rights as citizens of the Internet. That is, after all, what 90% of what’s written on this topic amounts to (the other 10% can be found mostly on the opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal). I, however, am going to give you something different: 11 things I learned about net neutrality while spending way too much time studying the topic over the past few days. I remain anything but an expert (and I ask the communications lawyers among you in particular to please point out any errors in the comments), but I thought a semi-neutral take on net neutrality might make for a nice change of pace this week.

1. The judges did it. The reason we’re having to suffer through this net neutrality discussion yet again is because three judges on the D.C. Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals (two appointed by Bill Clinton and one by Ronald Reagan) ruled in January that the previous set of “open Internet” (that’s what the FCC calls net neutrality) standards violated the law and the agency’s own rules. The problem, the court said, was that the FCC’s bans on blocking or discriminating against certain Internet traffic sounded like the kind of rules that would apply to a “telecommunications service,” yet the FCC has classified broadband internet as an “information service.” So while two of the three judges (the Clinton appointees) agreed that the FCC had the right to regulate broadband providers’ relationships with content providers (the FCC term is “edge providers”) even if it classified broadband as an information service, they didn’t think the agency had done it correctly up to now. The majority jovially encouraged the FCC to try again (“After all, even a federal agency is entitled to a little pride,” wrote Judge David Tatel), an effort that Chairman Wheeler hopes to launch at a Commission meeting this Thursday.

2. This “telecommunications” vs. “information” thing isn’t just technical minutiae. The terminology comes from the Telecommunications Act of 1996, but the concepts date back to the 1970s, when the FCC began to differentiate between basic telephone service and the cool new things people were beginning to do with computers over telephone lines. Telecommunications services are common carriers, expected to provide basic service on equal terms to all — and to let other businesses make use of their infrastructure to provide information services. These information services, the thinking went, were better left free to innovate and compete largely exempt from FCC regulation. In the early days of the consumer internet, the hundreds of competing dialup ISPs that piggybacked on existing phone lines fell clearly in the information services category. But in 1998, the FCC decided that the broadband DSL connections provided by telcos amounted to a telecommunications service. In 2002 the Commission switched course again and ruled that broadband access provided by cable TV companies was an information service — the reasoning being, in part, that cable broadband had ended the DSL monopoly and created a competitive market once again. This led to a zillion lawsuits from phone companies and other non-cable ISPs, but in 2005 the Supreme Court decided that the FCC was within its rights to make that call. After that, just to be fair, the FCC deemed DSL and other broadband services to be information services as well. But that hasn’t stopped cable companies from becoming the dominant providers of broadband access, with DSL a clearly inferior option and the much-anticipated buildout of fiber-optic networks by the telcos going more slowly than hoped.

3. It’s been a great decade to be a telecommunications lawyer. By classifying broadband as an information service, the FCC was effectively pledging to leave it alone. But when Comcast started blocking BitTorrent and other peer-to-peer sharing services because it said they were using too much bandwidth, the Commission jumped in and, in 2008, determined that Comcast’s behavior “unduly squelches the dynamic benefits of an open and accessible Internet.” Comcast sued, and the D.C. Court of Appeals (with Clinton appointee David Tatel writing the majority opinion there, too) ruled in 2010 that the FCC had failed to offer adequate justification in the law for its actions — it had basically just cited some vague exhortations from the Communications Act of 1934. By then Democrat Julius Genachowski, an avowed net neutrality fan, was in charge at the FCC. After floating a trial balloon about re-reclassifying broadband as a telecommunications service, the Commission decided instead to draw up a set of open Internet rules that it based on some less-vague exhortations in the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Verizon Communications challenged these in court, which led to the January Appeals Court ruling.

4. Republicans are from Comcast, Democrats are from Google. The pro-net-neutrality camp wants more regulation of broadband providers, which sounds like kind of a Democratic thing. But many of its members are convinced that this regulation is needed to preserve the Schumpeterian, creative-destructive free-for-all of the Internet, which sounds like something Republicans would be for. Also, dislike of the cable industry is a nonpartisan emotion: I would guess that if you asked Republican voters, “Should cable companies be regulated like electric utilities?” the most common answer would be, “You betcha.” And while a decade ago the entities on the side of net neutrality (the term is usually traced to a 2003 paper by Columbia Law School professor Tim Wu) were mostly cuddly little nonprofits and startups — and thus presumably endearing to Democrats — some are now multinational giants. Google has about the same revenue and profits as Comcast, and more than twice the market capitalization. So increasingly, this fight pits one set of gigantic capitalist entities that happen to be preferred by Democratic politicians against another set preferred by the Republicans. It didn’t start out this way: The Telecommunications Act of 1996, with its push for competition and lighter regulation, was a bipartisan effort. The 2005 Supreme Court dissent arguing that of course cable broadband was a common-carrier telecommunications service was the work of arch-conservative Antonin Scalia. The FCC chairman who went after Comcast in 2008 was Bush appointee Kevin Martin. Now, however, the rhetoric, the FCC votes, and even the court rulings are increasingly breaking down along partisan lines.

5. We’re on a slippery slope to a walled garden. Or something. On the face of it, the fact that Comcast and Verizon want Netflix, which accounts for 28% of all fixed-line Internet traffic in the U.S., to pay for some of that bandwidth it’s hogging does not seem all that alarming and unreasonable — unless you work at Netflix. The concern is what comes next. Mr. Net Neutrality himself, Tim Wu, writes that “bloggers, start-ups, or nonprofits” will “be behind in the queue, watching as companies that can pay tolls to the cable companies speed ahead.” That’s a bit rich — companies like Netflix and Google and Facebook already spend zillions of dollars ensuring that their content gets delivered more quickly and reliably that that of your average blogger, start-up, or nonprofit. They’ve just been spending it on server farms, undersea cables, and cloud services, not deals with ISPs. Yes, the companies with control over the “last mile” into consumers’ homes are in a special and uniquely powerful position, and there are reasons to suspect that the cable companies in particular would love to turn the freewheeling Internet into a “walled garden” of selected and paid-for content and to disadvantage those, like Netflix, who compete directly with their own offerings. There are also reasons to suspect that competitive forces and/or the FCC will stop them. There’s also the example of the mobile internet, which the FCC exempted from some of its open internet rules because there’s less bandwidth available and more direct competition. Smartphone screens definitely have a walled-garden aspect to them, but the vegetation has nonetheless grown pretty freely and riotously, and the chief gardeners have turned out to be Apple and Google — not the wireless phone companies.

6. That’s not the only slippery slope. The argument from the other side is that if the FCC succeeds in laying down strict rules on how broadband providers may interact with content providers, then that could bring all innovation and evolution in broadband to a halt. “An unwarranted government interference in a functioning market is likely to persist indefinitely, whereas a failure to intervene, even when regulation would be helpful, is likely to be only temporarily harmful because new innovations are constantly undermining entrenched industrial powers,” Judge Laurence Silberman (the Reagan appointee) wrote in his partial dissent to January’s Appeals Court decision. (Then, just to be snarky, Silberman supported his assertion with a quote from Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires: “[J]udicial errors that tolerate baleful practices are self-correcting while erroneous condemnations are not.”) This reflects the standard conservative line on antitrust, which can be traced back to the University of Chicago Law School classroom of Milton Friedman’s brother-in-law, Aaron Director: monopolies may be bad, but competition usually wears them down, while government regulations are forever. Although of course in the FCC’s case, regulations only seem to last until the next Appeals Court decision.

7. An open Internet does seem like a good thing. There is widespread agreement among economists that the current open, modular nature of the Internet has stimulated innovation and growth. The debate is really over whether enforcing that openness by regulatory decree is necessary or even helpful. If Internet openness really is as great as it seems to be, one line of reasoning goes, then it will win out in the end anyway. The counterargument, made in economist Joseph Farrell and legal scholar Philip J. Weiser’s 2003 paper “Modularity, Vertical Integration, and Open-Access Policies,” is that if firms in gatekeeper positions such as broadband providers have monopoly power, they may do things that are in their own short-term interest yet reduce the overall economic value of the networks to which they provide access. American communications history offers some support for this contention: The first great U.S. communications network was the Post Office, which was run by the government. As historian Richard John tells it in Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse, Congress gave itself the power to determine postal routes in 1792 and subsequently expanded the postal system much faster than any profit-seeking businessperson (or even halfway cost-conscious bureaucrat) ever would have. This legislative involvement has in recent years become the USPS’s Achilles heel, as Congress won’t allow it to cut back on activities that lose billions. But in the early days it was crucial to building the national economy, and the nation. In his subsequent book Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications, John makes the case that the next great communications network, the telegraph, expanded much less quickly as a private monopoly than it would have if inventor Samuel Morse had succeeded in getting postal authorities to take it over, as he initially hoped. And of course the one-time phone monopoly AT&T, while birthing all sorts of amazing innovations at its Bell Labs, was legendarily reluctant to give innovative competitors access to its customers.

8. Just because something is a good thing doesn’t make it the law. The big problem the FCC has faced in all its attempts to impose its open Internet ideas upon broadband providers is that Congress has never explicitly asked it to do such a thing. Over the past decade several bills have been proposed to rectify this lack of direction, but none have made it far. So the FCC has, as noted above, fallen back on a section of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that directs it to take “measures that promote competition in the local telecommunications market or other regulating methods that remove barriers to infrastructure investment.” In its open internet rules, the FCC basically argues that preventing broadband providers from discriminating against certain content will stimulate demand for broadband, which in turn will stimulate more infrastructure investment. Not for nothing did Verizon’s lawyers refer to this reasoning as a “triple bank shot.” There was a time when such regulatory creativity was applauded in the courts, but that ended sometime in the 1970s. What’s interesting is that the January Appeals Court decision (and even the dissent) made clear that the FCC can expect little trouble from the courts if it takes actions that directly promote competition or remove barriers to investment. One such measure, which Chairman Wheeler has already promised is on the way, would be to preempt the despicable laws that at least 20 states have enacted (under heavy lobbying from the cable companies and telcos) to prevent municipalities from building their own broadband networks. But surely there’s much more the agency could do in that direction.

9. The most obvious solution may not be the solution. FCC could also just reclassify broadband providers as telecommunications services, giving it far more power to regulate their behavior. Chairman Wheeler has said this option is still on the table, but he doesn’t seem to be planning to make use of it anytime soon. Why not? My guess is that it’s some combination of (1) wanting to get some new broadband rules out quickly to fill the current regulatory void, which requires continuing on the same track rather than starting over on a new one, (2) fear of the legal and political blowback that would surely ensue, and (3) genuine belief that competition is a better solution to whatever might ail broadband than common-carrier regulation would be. If broadband were classified as a telecommunications service, for example, the law points toward a requirement that cable companies and telcos open up their broadband lines to rival providers of internet access. This could remove much of the incentive for companies to string new, even-broader-band lines into Americans’ homes. The FCC could then try to build in new incentives through regulation and subsidy, but that would obviously bring its own complications. In a very interesting petition filed with the FCC last week, the Mozilla Foundation (the people behind the Firefox web browser and some other stuff) proposed a middle ground of continuing to treat the relationship between broadband providers and consumers as an information service, but regulating the interactions between broadband providers and content providers as a telecommunications service. I have no idea if that would stand up to legal scrutiny, but I like the creativity.

10. Broadband internet service in the U.S. is … okay. As of 2012, the U.S. ranked 20th in the world in the number of fixed-line broadband connections per 100 people. This and other global measures of broadband penetration are often trotted out to make the case that this country is a terrible laggard in the field, but I’m not so sure of that — all but one of the nations ahead of it on the list are much smaller and more densely populated, and even the exception, Canada, has a population concentrated along its southern border rather than strewn all over as in the U.S. So the performance of broadband providers here seems neither brilliant nor dismal. And unlike in Europe, where economic troubles and budget cuts have curtailed broadband plans, the forecast for the U.S. seems to involve continued, if not exactly consistent, buildout — with Google Fiber and AT&T’s planned Ultra-Fast Fiber Network currently generating the most excitement. Interestingly, mobile broadband penetration in the U.S. ranks much higher, at ninth in the world. That could have something to do with it being easier to upgrade a small-town cell-phone tower than to string new wires to everybody in town, or it could be a reflection of a much more competitive market in wireless broadband than in the wired variety. Or both.

11. Cable companies are a long way from winning the hearts and minds of American consumers. The American Customer Satisfaction Index gives Internet service providers (the cable industry) a score of 65 for 2013 — the worst of any industry tracked — with hoping-to-merge giants Time Warner Cable and Comcast at even more dismal scores of 63 and 62, respectively. Subscription television services (the cable companies plus the better-liked satellite and telco providers) get a slightly better rating of 68, with Comcast at 63 and Time Warner Cable at 60. Electrical utilities, by contrast, score a perfectly respectable 77. The public sector rates a weak-although-still-better-than-cable 68, the much-criticized airlines score 69, and health insurers come in at 73. There’s no ranking for newspapers in 2013, although in some past years they’ve done even worse than cable. Interestingly, both newspapers and cable for decades followed the same simple business strategy: (1) acquire a local monopoly, (2) squeeze the greatest possible profits out it. In a generally admiring account of the rise of cable pioneer John Malone in his book The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success, Will Thorndike describes how Malone starved his cable systems of resources because he “saw no quantifiable benefit to improving his cable infrastructure.” It was only the arrival of competition from satellite TV in the mid-1990s that changed his tune. Malone was (and is) an extreme case, but in general pleasing customers and pursuing technological innovation don’t really seem to be in the cable providers’ DNA. Given that, it’s actually pretty remarkable how much they’ve accomplished in broadband over the past decade. Going forward, though, the question is whether the cable industry’s history should lead us to fear what it might do to the Internet — or chuckle at its hopes of outmaneuvering the likes of Amazon, Apple, and Google.

The Best Leaders Are Humble Leaders

In a global marketplace where problems are increasingly complex, no one person will ever have all the answers. That’s why Google’s SVP of People Operations, Lazlo Bock, says humility is one of the traits he’s looking for in new hires. “Your end goal,” explained Bock, “is what can we do together to problem-solve. I’ve contributed my piece, and then I step back.” And it is not just humility in creating space for others to contribute, says Bock—it’s “intellectual humility. Without humility, you are unable to learn.”

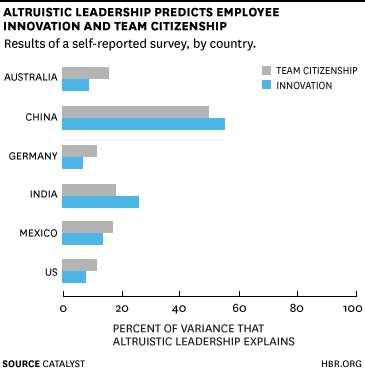

A recent Catalyst study backs this up, showing that humility is one of four critical leadership factors for creating an environment where employees from different demographic backgrounds feel included. In a survey of more than 1500 workers from Australia, China, Germany, India, Mexico, and the U.S., we found that when employees observed altruistic or selfless behavior in their managers — a style characterized by 1) acts of humility, such as learning from criticism and admitting mistakes); 2) empowering followers to learn and develop; 3) acts of courage, such as taking personal risks for the greater good; and 4) holding employees responsible for results — they were more likely to report feeling included in their work teams. This was true for both women and men.

Employees who perceived altruistic behavior from their managers also reported being more innovative, suggesting new product ideas and ways of doing work better. Moreover, they were more likely to report engaging in team citizenship behavior, going beyond the call of duty, picking up the slack for an absent colleague — all indirect effects of feeling more included in their workgroups.

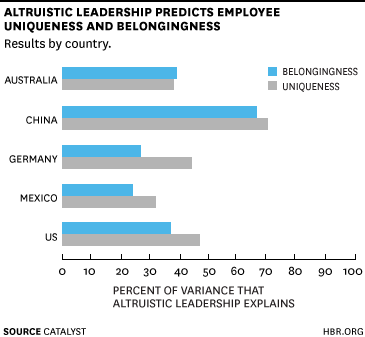

Our research was also able to isolate the combination of two separate, underlying sentiments that make employees feel included: uniqueness and belongingness. Employees feel unique when they are recognized for the distinct talents and skills they bring to their teams; they feel they belong when they share important commonalities with co-workers.

It’s tricky for leaders to get this balance right, and emphasizing uniqueness too much can diminish employees’ sense of belonging. However, we found that altruism is one of the key attributes of leaders who can coax this balance out of their employees, almost across the board.

Nonetheless, our study raises one common, perhaps universal implication: To promote inclusion and reap its rewards, leaders should embrace a selfless leadership style. Here are some concrete ways to get started based on both our current research and our ongoing study of leadership development practices at one company, Rockwell Automation:

Share your mistakes as teachable moments. When leaders showcase their own personal growth, they legitimize the growth and learning of others; by admitting to their own imperfections, they make it okay for others to be fallible, too. We also tend to connect with people who share their imperfections and foibles—they appear more “human,” more like us. Particularly in diverse workgroups, displays of humility may help to remind group members of their common humanity and shared objectives.

Engage in dialogue, not debates. Another way to practice humility is to truly engage with different points of view. Too often leaders are focused on swaying others and “winning” arguments. When people debate in this way, they become so focused on proving the validity of their own views that they miss out on the opportunity to learn about other points of view. Inclusive leaders are humble enough to suspend their own agendas and beliefs In so doing, they not only enhance their own learning but they validate followers’ unique perspectives.

Embrace uncertainty. Ambiguity and uncertainty are par for the course in today’s business environment. So why not embrace them? When leaders humbly admit that they don’t have all the answers, they create space for others to step forward and offer solutions. They also engender a sense of interdependence. Followers understand that the best bet is to rely on each other to work through complex, ill-defined problems.

Role model being a “follower.” Inclusive leaders empower others to lead. By reversing roles, leaders not only facilitate employees’ development but they model the act of taking a different perspective, something that is so critical to working effectively in diverse teams.

At Rockwell Automation, a leading provider of manufacturing automation, control, and information solutions, practicing humility in these ways has been essential to promoting an inclusive culture — a culture Rockwell’s leaders see as critical to leveraging the diversity of its global workforce.

One of the key strategies they’ve adopted to model this leadership style is the fishbowl — a method for facilitating dialogue. At a typical fishbowl gathering, a small group of employees and leaders sit in circle at the center of the room, while a larger group of employees are seated around the perimeter. Employees are encouraged to engage with each other and leaders on any topic and are invited into the innermost circle. In these unscripted conversations, held throughout the year in a variety of venues, leaders routinely demonstrate humility —by admitting to employees that don’t have all the answers and by sharing their own personal journeys of growth and development.

At one fishbowl session, shortly after the company introduced same-sex partner benefits in 2007, a devoutly religious employee expressed concerns about the new benefits policy — in front of hundreds of other employees. Rather than going on the defensive, a senior leader skillfully engaged that employee in dialogue, asking him questions and probing to understand his perspectives. By responding in this way, the leader validated the perspectives of that employee and others who shared his views. Other leaders shared their own dilemmas and approaches to holding firm to their own religious beliefs yet embracing the company’s values of treating all employees fairly. Dialogues such as these have made a palpable difference at Rockwell Automation. Employees have higher confidence in their leaders, are more engaged, and feel more included — despite their differences.

As the Rockwell example suggests, a selfless leader should not be mistaken for a weak one. It takes tremendous courage to practice humility in the ways described above. Yet regrettably, this sort of courage isn’t always rewarded in organizations. Rather than selecting those who excel as self-promotion, as is often the case, more organizations would be wise to follow the lead of companies like Google, Rockwell Automation, and others that are re-imagining what effective leadership looks like.

Robots Are Starting to Make Offshoring Less Attractive

The hype around robots taking jobs is reaching a crescendo, in response to an insightful new book The Second Machine Age by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, as well as an Oxford Martin School study: ‘The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization?‘ The former states that digital technology and robotics are advancing at such a pace that: “Professions of all kinds — from lawyers to truck drivers — will be forever upended. Companies will be forced to transform or die.” The latter claims that up to 47 percent of American jobs are susceptible to robots and automation within the next seven to 10 years.

Despite the doom and gloom, advances in robotics and associated technology are having a positive impact on local manufacturing and services and both sustaining and creating jobs. In developed economies, they have even sparked a trend toward the return of jobs from overseas, or “botsourcing.” This new wave of bringing production back home through robotics automation may be the single biggest disruptive threat to India’s $118 billion information technology industry. The more processes can be automated, the less it makes sense to outsource activities to countries where labor is less expensive.

The threat is being taken seriously elsewhere in Asia as well. Foxconn, the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer best known for manufacturing the iPhone, has recently announced it will spend $40 million at a new factory in Pennsylvania, using advanced robots and creating 500 jobs.

Thanks to one of the most advanced robotic manufacturing facilities in the world, Tesla Motors builds its electric cars entirely in the US.

In each of these cases, the combination of advances in robotics and automation and rising wages in developing countries has upended the promise of cost reductions through outsourcing. Sutherland Global Services, an outsourcing company in Rochester, NY, says it can reduce costs for its clients between 20 and 40 percent by shifting IT work to a developing economy, but it can reduce costs by up to 70 percent if it uses automation software coupled with its U.S.-based employees to complete tasks involving high volumes of structured data.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman writes in his book The Age of Diminishing Expectations: “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

The same is true of business: profits increase (or decrease) in proportion to the output per worker. Shifting work to places where labor is cheaper is one way to improve this in the short term. But over time technology is a far more reliable path to increased productivity.

In March 2012, Amazon announced the $775 million cash acquisition of Kiva Systems, a warehouse automation robotics company. By October 2013, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos noted that they had “deployed 1,382 Kiva robots in three Fulfillment Centers.” Yet Amazon continues to significantly grow its number of employees in these fulfillment centers, adding 20,000 full-time employees in the U.S. last year. This year, when the company announced that it was hiring an additional 2,500 full time U.S. fulfillment staff, it emphasized that the jobs had a 30 percent pay premium over traditional retail jobs. Technology done well doesn’t just replace workers, but makes them more productive.

For managers, the trend toward botsourcing will require a shift in thinking. Rather than moving operations to wherever work costs the least, consider which pieces can be automated, and how best to combine human and robotic expertise.

Attracting Top Contributors to an Open Innovation Project

“Not all smart people work for you,” begins Henry Chesbrough’s classic 2003 HBR article on the merits of open innovation. Firms must find a way to tap into external knowledge and ideas to innovate. Today, this premise is the basis for crowdsourcing, crowdfunding, open source development, and more. In each case, firms face a challenge: how to attract and motivate the best external contributors.

A recently published paper by researchers at Duke and the London School of economics sheds light on this issue by studying contributions to open source software. It suggests that to attract the most productive contributors, companies may have to give up more control over their project. At the very least, they need to consider the values of the community they’re hoping to attract, and not just offer financial or professional incentives.

In an attempt to determine what motivates open source contributors, the researchers looked at data from SourceForge.net, a site that hosts open source software projects. They measured various factors that might affect a developer’s chances of contributing to a project, like whether contributions were credited publicly, whether the project had a corporate sponsor, and what kind of software licensing the project used.

While they found that different types of projects attract different types of contributors, one consistent finding across types of contributors and projects was the importance of reputation as a motivator for contributing. Projects that more frequently publicly credited contributors attracted more contributions. This finding is consistent with recent research from Harvard on the motivations of Wikipedia contributors, which found evidence that social image is a primary motivator. For open innovation projects, the lesson is clear: make contributions transparent, and design tools that validate top contributors’ status in the group.

Giving credit is easy enough, but one of the paper’s other key findings points to a tradeoff for companies between attracting talented contributors and maintaining control. The authors found that developers who mostly contribute to openly licensed projects, or who contributed anonymously, were far more productive than those who mostly contributed to more commercially oriented projects. They attribute this to the power of intrinsic motivation.

The authors argue that to attract more of these highly productive, intrinsically motivated developers, firms must consider licensing their software projects more openly. (Open source software licenses vary, from those that are very friendly to commercial activity and so “less open,” to those that require all future variations of the code be made freely available, and so are “more open.”)

This lesson applies beyond software, and is ultimately about more than control. Developers in the open source community are often motivated by an ideological preference for openly licensed software. Hence this intrinsically motivated group gravitates to such projects. Firms considering any kind of open innovation — crowdsourcing a new product idea, encouraging app development based on one of its platforms, etc. — must appeal not just to professional or financial rewards. They must tap into the values of the community they’re looking to engage.

That could mean making a project more open, prioritizing a social aim alongside a commercial one, or investing the firm’s time and money into other open projects valued by the community of interest. These commitments might make open innovation more expensive in the short-term, but they may well pay for themselves by bringing more talented contributors to the table.

Can You Be Too Rich?

Is there such a thing as too rich?

Like most reasonable people, I agree whole-heartedly that people who accomplish greater, worthier, nobler things should be rewarded more than those who don’t. I’m not the World’s Last Communist, shaking his fist atop Karl Marx’s grave at the very idea of riches.

So. Perhaps I’ve asked an absurd question. Perhaps there’s no such thing as too rich — anywhere, ever. But try this thought experiment: Imagine that there’s a single person in the economy who is so rich he’s worth what everyone else is, combined. If there were such a person, he’d be able to buy everything the rest of us own. In time, his family, inheriting his wealth, would become a dynasty; and he could, by bestowing favors, direct the course of society as he so desired. In all but name, such a person would be a king; and no one else’s rights, wishes, desires, or aims could truly matter. And so no society with such a person in it could be reasonably said to be free.

It seems to me, then, there is such a thing as too rich, at least for people who wish to call themselves free. The only question is: Where is the line is drawn? How rich is too rich?

Imagine that you’re so rich you can afford the finest of every good in the economy. The best education, the best car, the best champagne, and so on. Would that be a justifiable level of wealth for a person to not just enjoy — but to aim for? A lot of people would probably say yes.

Now imagine you’re so rich that you can buy the finest of every good in the economy not just once — but 10 times over. Everything. The 10 finest homes. Meals. Doctors. Servants. Entire wardrobes. Apartments, mansions, investment portfolios. The 10 best yachts. Ten private jets. Would that be an excessive level of wealth?

Suddenly, such a level of wealth begins to sound not just unreasonable, but senseless. After all, what possible purpose could owning 10 gigantic homes, yachts, or jets serve? Why should anyone want to be that rich? Not just rich — but super rich?

What is it that induces a sense of repugnance in many of us — in most sensible people — about not just riches, but super-riches? Why is it that when an invisible line is crossed, our attitudes to wealth transform from admiration, to repulsion?

The doctor; the businessman; the neighborhood banker — all these are likely to be merely rich; and probably, many would argue, justifiably so. Their riches can be evidently seen to reflect a contribution to the common wealth. There is a purpose to their work, which requires long years of training and discipline, to which society rightly assigns a steep value.

But to paraphrase the famous line from The Great Gatsby: the super-rich are very different from the merely rich. The super-rich are not just worth millions; but billions. And they are not doctors; businessmen; bankers. They are hedge fund tycoons; “private equity” barons; privateers who have bought the natural resources of entire countries whole; CEOs with golden parachutes the size of small planets. And their wealth is questionable; not just in moral terms, but also in economic ones. For what useful purpose do speculation, profiteering, and company-flipping serve? In what way do they benefit the societies that incubate them?

The rich, if they do not plant prosperity’s seeds, at least tend to its branches — but the super-rich appear to be merely picking off the choicest fruit.

When societies allow the rich to grow into the super-rich, they are making a series of mistakes. The mistake is not just that a class of super-rich are fundamentally undemocratic because they hold the polity ransom. The mistake is not just that a class of super-rich is fundamentally uneconomic because the super-rich hoard vast amounts of capital, starving the economy of investment, opportunity. The mistake is not just that a class of super-rich is fundamentally inequitable because it is essentially impossible that any human being has single-handedly truly created enough value to be worth tens of billions. The mistake is not just that a class of super-rich is fundamentally unreasonable because there is no good reason for anyone to want such extreme riches. The mistake is not just that a class of super-rich is fundamentally antisocial, for the super-rich will never have to rely on public goods in the same way that the merely rich still need parks, subways, roads, and bridges.

All those are small mistakes. Here is the big one.

When societies allow the rich to grow into the super-rich, they are limiting what those societies can achieve.

Imagine a bountiful forest. And then — no one can say quite why — a small handful of the trees suddenly grow tall. Much taller. They became so tall and strong and broad that they block the sunlight from all the other trees. The other trees begin to wilt, and wither, and disappear. Their roots crack, and split, and turn to dust. And one day, not long after, even the roots of the tallest trees can find no water, can grip no soil. They begin to fall. Soon the whole forest becomes a desert.

A dry academic term like “income inequality” doesn’t really begin to cover it, does it?

When super-riches grow unchecked, no one wins — not even the super-rich themselves, in the long run. Everyone’s possibility is stifled when the invisible line from rich to super-rich is crossed. And that is precisely why no society should desire a class of super-rich; for it assures us that a society’s human potential will be eroded. And that is precisely why the moral sentiments of most reasonable people are instinctively, naturally opposed to the idea of super riches.

At this juncture, I’m sure that defenders of free markets will complain: Who are you to say that anyone shouldn’t be super-rich? But it is precisely defenders of free markets who should object most vehemently to the super-rich. I defy you to find me a fully-fledged member of the super-rich today who isn’t a monopolist, a scion, an oligarch … or all three.

Is there such a thing as too rich?

Here is my answer: No forest should become a desert.

Road Metaphors Are Powerful in Encouraging Goal-Directed Action

University freshmen put more effort into an academic task after thinking about their futures as a physical journey than after thinking of their coming years as a series of boxes, says a team led by Mark J. Landau of the University of Kansas. After being asked to visualize themselves as seniors and viewing an image of their undergraduate years as a path extending into the distance, the research participants solved 50.8% of a set of mental arithmetic problems; those who had viewed a metaphorical image of their years as a set of wooden trunks solved just 38.9%. The findings suggest that corporations, as well as sports teams and health communicators, might do well to employ journey-framed metaphors to encourage goal-directed action.

What an Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Actually Is

Fostering entrepreneurship has become a core component of economic development in cities and countries around the world. The predominant metaphor for fostering entrepreneurship as an economic development strategy is the “entrepreneurship ecosystem.” It should come as no surprise, however, that as any innovative idea spreads, so do the misconceptions and mythology. Here is a quick true-false test that will serve as a reality check on entrepreneurship ecosystems, and on the connection between entrepreneurship and development more generally. It’s important to get this right, because the emergence of entrepreneurship as a policy priority has paralleled (and is at least partly in response to) disappointment with dictated industrial policy, barren “cluster” strategies, and the failure of a limited focus on a set of macroeconomic framework conditions (the so-called “Washington Consensus”). If we’re to prevent the enthusiasm for entrepreneurial ecosystems from also fizzling out, we need to get a better grip on what the term really means.

You know that you have a strong entrepreneurship ecosystem when there are more and more startups.

False. There is no evidence that increasing the number of startups per se or new businesses formation stimulates economic development. There is some evidence that it goes the other way around, that is, economic growth stimulates new business creation and startups. There is also some reason to believe that the number of small businesses is negatively related to national economic health and the Kauffman Foundation recently reported that as the US economy is improving and good jobs are increasing, the number of startups is decreasing. In fact, encouraging startups may be bad policy.

Offering financial incentives (e.g. angel investment tax credits) for early stage, risky investments in entrepreneurs clearly stimulates the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

False. There are actually few, if any, good evaluations of the impact of near-ubiquitous angel tax credits. One study of one of the oldest such schemes, the Entreprise Investment Scheme, started in England in 1994, suggests that it stimulated a significant increase of small investments (less than $10,000) by inexperienced investors who believed they received worse returns than the alternatives. In fact, the majority of venture capital investments are in California, New York, Massachusetts, and Israel, with no direct financial incentives other than fully-taxable profits.

Job creation is not the primary objective of fostering an entrepreneurship ecosystem.

True. Because no one owns or represents an entrepreneurship ecosystem, there can be no one objective that motivates all of the actors. The motivation for fostering entrepreneurship entirely depends on who the actor or stakeholder is. For public officials, job creation and tax revenues (fiscal health) may be the primary objectives. For banks, a larger and more profitable loan portfolio may be the benefit. For universities, knowledge generation, reputation, and endowments from donations may be the benefits. For entrepreneurs and investors, wealth creation may be the benefit. For corporations, innovation, product acquisition, talent retention, and supply change development may be the benefits. Many stakeholders must benefit in order for an entrepreneurship ecosystem to be self-sustaining.

In order to strengthen your regional entrepreneurship ecosystem, it is necessary to establish co-working spaces, incubators and the like.

False. There is no systematic evidence that co-working spaces contribute significantly to growing ventures. There are many anecdotes of high-growth ventures in all segments which got their starts in incubators, but there are also many more examples, less visible perhaps, of very success ventures that made no use of co-working space. Some entrepreneurs find that co-working spaces diminish their creativity or distract them from their focus. Others feel that the network gives them access to information and ideas. Whether they are a help or a hindrance, these types of intentionally created support mechanisms are at most just a small sliver of the entire entrepreneurship ecosystem, and whereas they may be helpful, they are not necessary.

If we want strong entrepreneurship ecosystems we need strong entrepreneurship education.

False. Surprisingly, there is no reason to believe that formal education in entrepreneurship leads to more, or more successful, entrepreneurship; there is, however, some evidence that it is irrelevant. Well-known entrepreneurial hotspots such as Israel, Route 128, Silicon Valley, Austin, Iceland and others, had significant entrepreneurship long before there were courses in it. These arose organically, first and foremost due to access to customers and employable talent, as well as access to capital. I taught the first masters course on technological entrepreneurship in Israel at the Technion in 1987, 15 years after Israel’s first tech IPO on NASDAQ and when the entrepreneurial revolution in Israel was well underway. This is not to say that entrepreneurship education is not helpful, rather that it is probably not on the critical path to a regional entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Entrepreneurs drive the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

False. This is an oft-heard statement, but there is a critical difference between being one essential element out of many — which entrepreneurs clearly are — and being the driver. There is no one driver of an entrepreneurship ecosystem because by definition an ecosystem is a dynamic, self-regulating network of many different types of actors. In every entrepreneurship hotspot, there are important connectors and influencers who may not be entrepreneurs themselves. In Boston several bankers and professors were crucial catalysts in the 1970s and 1980s. In Israel there were three or four investors involved in many of the early successes. In emerging markets, NGOs such as Endeavor and Wamda have been key catalysts.

Large corporations stultify entrepreneurship ecosystems because they prey on entrepreneurs and their ventures.

False. Of course, many large corporations do indeed take defensive action against entrepreneurs who challenge their markets. But it is not possible to have a vibrant entrepreneurship ecosystem without a broad spectrum of business “flora and fauna.” This is true for a variety of reasons, two of which are: (1) corporations are important customers and market channels for entrepreneurs, not just competitors, and (2) flows of talented executives to and from larger corporations feed entrepreneurial success. Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship definitely do not occur in a business vacuum.

According to entrepreneurs the top three challenges everywhere are access to talent, excessive bureaucracy, and scarce early stage capital.

True. But this does not mean that they are right. Whether in Boston, Tel-Aviv, Reykjavik, Milwaukee, St. Petersburg, Johannesburg, Buenos Aires, Rio or Bogota (all places where I have conducted workshops and have conducted informal surveys on the question) raising capital, finding talent, and overcoming bureaucracy are three of the top challenges entrepreneurs ascribe to their environments. As I have argued, this is such a ubiquitous phenomenon that it probably reflects something fundamental about the generic process of entrepreneurship, rather than a deficiency of the ecosystem. The process of entrepreneurship intrinsically generates a feeling that risk capital is difficult to raise and in short supply.

Banks are irrelevant for the entrepreneurship ecosystem because they don’t lend to startups.

False. Yes, it is true that banks don’t, and shouldn’t lend to startups. That is not the business they are in. Yet banks, even if they never directly engage or interact with entrepreneurs, help financial markets mature and indirectly impact the entire value chain of investing. In fact, bankers have made a lot of money investing in somewhat later stage technology companies, which in turn increased the confidence of early stage investors that if their investments grew, they would find the capital to fuel their expansion.

Family businesses squash entrepreneurial initiative in order to protect their “franchise.”

False. I have heard it said by well-known promoters of entrepreneurship that family businesses achieve scale or maximize their contribution to open markets while remaining family businesses because they, for the most part, achieve their growth through special connections and protections. Yet experience in even the most advanced economies (e.g. Denmark) suggests that corporations with ownership structures from family to public to cooperative are essential to, and highly facilitative of, the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

How well did you score? If you got over 50% correct, then you are in very exclusive company. The above reality check is just a starting point. Entrepreneurship does indeed create many positive economic and social spillovers, yet the only way that policymakers, civil society, corporate leaders, and entrepreneurs themselves can truly set the context for successful economic development is to separate myth from reality and shake free from the many misconceptions that exist. Only then will we be able to accelerate the formation of entrepreneurship ecosystems. They are too important to leave to chance.

May 9, 2014

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

Sometimes it’s relatively easy to know what your customers are doing. In e-commerce, advances in tracking and analytics have made it possible for retailers to understand what individual customers are doing before they make a purchase, and to gather and analyze hundreds and thousands of data points to identify trends.

Brick-and-mortar stores haven’t had the same advantage.

“Retailers are all using scanner data to track what happened at the point of sale,” says Sam Hui, an associate professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business. “But they have no idea what’s really happening at a point-of-purchase decision.”

This is changing with the emergence of location analytics. Take Alex and Ani, which designs and retails jewelry, and Belk, a department store chain. Both have signed on with Prism Skylabs, a software company, to map in-store customer behavior.

By using a store’s existing security cameras, or installing new ones, Prism (no relation to the NSA program) is able to track the movement of a store’s customers and identify patterns. “We’re not really looking at any individual; we’re looking at what a group of people over a period of time do,” says senior vice president of managed services Cliff Crosbie. “That’s the really big thing: Identifying what a volume of people do over a period of time, and how you read that information.”

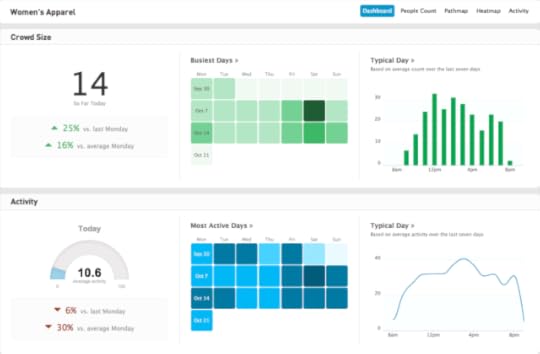

In many ways, Prism is capturing the simplest aspects of shopping, aspects ecommerce websites now take for granted. “Retailers want to know what parts of their store are busy, and where customers particularly shop. So, if there’s a promotion on, when do people stop there and what do they do?” Prism can also track what happens on individual days, or over time, using a dashboard like this (rather than reams of Excel spreadsheets):

These simple, color-coded data visualizations allow retailers to turn a store floor into an analytics narrative. (A new version also takes weather into account.)

Prism can also convey information on customer movements as a heat map. Consider this example from Alex and Ani during a pilot program during last year’s holiday season, which tracked customer movement on the floor over a three-week period. The redder the location, the more frequently it was trafficked:

For chief technology officer Joe Lezon, the results were both helpful and surprising. “We now know that there was a certain area in our store people went to more often,” he told me. “We also realized that 98% of the people turned right when they first entered the store.” Lezon, along with Alex and Ani’s head of merchandising and head of sales operations, used the data to inform product placement.

In one instance, a slower-moving product was moved to a more trafficked location, resulting in an uptick in sales. And when the location of store’s more popular items were shifted, Lezon and his team were able to watch the process by which customers were able to locate them.

Both Lezon and Greg Yin, Belk’s vice president of innovation, told me that the heat mapping is particularly valuable when it comes to maximizing the value of staffing – making sure customers have a salesperson to assist them, easing the burden of the busiest times on sales associates.

Yin also says collecting and visualizing this data has helped his company test out in-store assumptions quickly. “I don’t think we’re in a place in the industry right now where we can invest 12, 18 months in a long [research] project because the technology will have changed by then,” he explained. “It’s not about building out big, long-term solutions. It’s about building a foundation in our stores and online so we can move as our customer moves.”

And while there are some privacy concerns, Prism, unlike other kinds of online tracking, promises a level of anonymity.

“We’ve had cameras in stores for years,” Yin reminds me. “But the nice thing about Prism is that it’s anonymizing. There’s no personal data being reflected because it’s all aggregated.” At the same time, he recognizes that “when we’re talking about location-based marketing, we’re really talking about personalization.”

And when it comes to personalization, there has to be a give-and-take between the customer and the store; “research shows that many customers are willing to opt into these kinds of things as long as there’s some kind of [benefit] in exchange.”

He notes, however, that the kind of bartering with personal information that’s resulted in so many successful recommendation algorithms, for example, doesn’t necessarily translate to the in-store experience. “We have to understand that the online customer is different than the in-store customer, and that the expectations might be different,” he says. “When you get into facial recognition and trying to assess out the demographics of a customer coming into your store, then you’re getting into a little bit more of a gray area.”

And when it comes to just physically walking into a store, there’s no real way for a customer to opt out of becoming a data point that, presumably, might make the shopping experience better in the future. A 2013 Pew study found that 64% of American adults cleared their cookies and browser history to become less visible online; even Prism’s Cliff Crosbie notes that more people are switching off their WiFi in stores. While Prism’s technology removes the actual images of customers – something Crosbie says is “the right thing” to do – being tracked is still a hidden part of the shopping experience.

This is all the more important considering the fact that companies are just starting to experiment with how location analytics can both improve a shopper’s experience and boost their own sales. “We can correlate a slight uplift in the sales for slower moving products,” says Lezon.”But in general, this is a tough metric.”

“We could definitely see, after changing a display, the traffic really picking up there,” Yin explained. “The next obvious piece is to really be able to triangulate some sales against that.”

Those sales are what’s most important to Yin. “I don’t come in every morning and say, “How am I going to innovate today? That doesn’t really exist,” he explains. “The question is, ‘How do we drive business? How do we provide a great customer experience? How do we best equip our associates?”

“This is a really interesting time in retail,” he continues. “All of these technologies are starting to come together – whether it’s mobile, whether it’s social, whether it’s analyzing a lot of data – and they’re coming together to meet the customer. At the end of the day, understanding customer behavior in stores and being able to take actions on it is a problem we’re trying to solve.”

For Joe Lezon, the ultimate goal is the coupling of data based on a customer’s online and in-store experience.

“My ideal situation, to be honest, is: Gretchen, you walk into my store,” he says to me. “I know who you are. I know why you’re there: Your daughter’s birthday is next week and you want to buy her a gift. At the same time, I know what you’ve purchased in the past so I can actually help direct you to the right products.”

“How do you merge all the data together to get a full 360-degree view of the customer? That’s where all this is going.”

Imagine what that visualization might look like.

Editor’s note: This post was updated on May 9 at 2:30pm ET.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

Visualizing Zero: How to Show Something with Nothing

Case Study: Where to Launch in Africa

Benard Kenani spotted his uncle as soon as he walked into the hotel lobby. Uncle Michael was sitting at a corner table with two other men, also in suits, both of whom were laughing at one of his jokes. That was typical of Michael, a successful executive in Nigeria, whose affable disposition was widely admired. He quickly stood up when he saw his nephew.

“Welcome to Lagos!” he shouted across the room. He proudly introduced Benard to the others, referring to him as “one of Nigeria’s up-and-coming entrepreneurs.”

Right after the men left, Benard corrected his uncle. “You know I haven’t decided if Nigeria is the place to start my business yet.”

(Editor’s Note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.)

Michael shrugged off the comment. “What matters to me most is that you’re finally going out on your own, achimwene. It’s what you’ve always wanted. ”

Michael, like Benard, had been born and raised in Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi. Like many talented Malawians, he had left the country as a young man to seek opportunities elsewhere, settling in Nigeria a decade ago. He now ran a thriving manufacturing enterprise.

Benard had left Malawi, too, after winning a scholarship to study in the UK, where he’d completed both his university degree in economics and an MBA. But he’d been drawn back to Africa by the burgeoning opportunities there and a desire to be closer to home. After six years as a manager at a packaging company in Kenya, he now felt that he had enough experience to start his own business. His uncle, along with several other friends and family members, had committed to investing in it.

Benard was in Lagos to see his uncle and seek advice about where to establish himself. Though Benard had an ambitious vision of someday running a venture that spanned the continent, he knew he needed to focus on one country at the start.

“But you’re seriously considering Nigeria, right?” Michael said.

“Yes, of course.” Benard nodded as he opened his laptop. “The market is competitive, but my research suggests that there are still opportunities in some specialty packaging markets. I’ve run some projections.”

Michael interrupted Benard, closing his computer. “You just need to look around! The BBC, the New York Times, the Economist — the whole world is talking about how fast Nigeria is growing. We’re on the cusp of joining the G20. If you want to be on the forefront of Africa’s growth right now, Nigeria is the place to be.”

“I agree. There are many factors that make it an attractive market. If everything continues at this pace, I’m confident that I can be profitable in the next year or two,” Benard said. “But I’m also worried.”

He saw the puzzled look on Michael’s face as he continued, “The political environment makes me nervous. And I’ve been reading a lot recently about growing instability and how that could threaten the country’s prosperity.”

“Sure, those are risks, but you’re going to find risks everywhere. You also need to think about the upside of basing yourself in Africa’s largest economy. Where else are you considering?” Michael asked, quickly adding, “Wait…don’t tell me Malawi.”

Benard gave his uncle a nervous smile. He knew this was coming.

“Benard, when did you become so sentimental? Your vision is so much bigger!”

“With the expertise I can bring to the business, within a year I’ll be the number one packaging manufacturer there —”

Michael quickly stopped him. “But what does that matter? Number one in Malawi?”

“That’s just the start. Malawi will give me a base to launch into other east African markets — Zambia, Mozambique, Rwanda, even Tanzania — and then move into other businesses. I don’t want to be stuck in one place. I want to build across markets to achieve scale. ”

The apprehension on Michael’s face made Benard realize he should try a different approach. “Abambo, remember when you started out here in Nigeria, it wasn’t such an enormous economy. As the country has grown, so has your business. There are other smaller African economies poised for growth, and I can be a part of it. I already have a potential business partner in Lilongwe that can help get me started.”

“If that’s what you’re concerned about,” Michael interjected, “I can line you up with three potential partners here tomorrow. Just say the word.” He asked Benard when he expected to make a decision.

“Soon,” Benard said. He explained that he had told his boss that he would be leaving to start a new venture and had taken the week off to finalize his plans for it.

“I will support your business no matter what you decide,” Michael said. “But you need to think about where the money is now. That’s where you want to be.”

The Potential of Malawi

The following day, Benard flew to Lilongwe. He was eager to meet with Amara Desta, his potential business partner in Malawi. She had inherited a small packaging business from her father. Because she’d been preoccupied with several other successful entrepreneurial ventures, however, she’d done little to develop it. For the past year, Amara had been looking for ways to divest the business, ideally by finding someone to buy a majority stake from her. Benard’s father had introduced them during his last visit home.

“I simply haven’t had the time to put into the business,” Amara explained as she showed Benard around the manufacturing facility. Indeed, many of the machines were outdated, and several were no longer functioning. “Luckily, we’re still in the enviable position of often having more orders than we can fill. Your father probably mentioned that our customers are primarily tobacco producers.”

Tobacco accounted for more than 70% of Malawi’s exports, and tobacco packaging offered some of the most attractive margins among the products sold by Benard’s current employer in Kenya. If he just made a few equipment purchases and built off Amara’s existing relationships, he could get started right away. But he also realized that it was risky to set up a business where almost all the demand would come from one sector.

“You must enjoy being back home,” Amara said.

“Yes, I would love to spend more time here,” Benard responded, thinking about his childhood in Lilongwe. His family, as well as many of his friends, were still nearby. “Attractive as it is on the personal side, I want to make this decision objectively, based on the economics.”

“Malawi has more to offer than most people think,” Amara noted as she proudly rattled off a list of the country’s recent improvements to him as if he were a visitor, not a native. Though the 10 years Benard had been away from Malawi hadn’t felt long, he understood why those who’d stayed now treated him like an outsider.

“And the demand is there,” Amara continued. “The tobacco growers would love to buy packaging in country. Right now, the costs to import packaging are exorbitant. Producing domestically would dramatically lower them, and we’d quickly capture much of the market. We’re perfectly situated for later expansion into other markets in east Africa too, if that’s of interest to you.”

Benard agreed to be in touch with Amara in the coming week and excused himself to go meet his father, Kwende, for lunch.

Kwende was eager to hear about Benard’s meeting with Amara. “There’s lots of potential there, right?” Kwende asked enthusiastically. “It seems like a good partnership. You both bring such assets to the table.”

“It’s true. But, abambo, I know you want me here, and I think that’s clouding your judgment.”

“Listen, I’m not as successful as your uncle Michael, but I’ve been looking into this. Start in Malawi, and after you’ve succeeded here move into other countries. Focusing on one of the bigger markets like Nigeria and Kenya may seem safer now, but that can always change. By diversifying into several smaller markets, you’ll still have a business if there is political or economic upheaval in one place.”

“I’ve thought about that. In fact, the woman I spoke to in Rwanda argued the same thing.” Benard had been in touch with the head of the Rwanda Development Board, a government agency that was providing incentives for small-business owners as part of its postgenocide rebuilding efforts. She’d made several compelling arguments for establishing the business there, including a growing economy and reduced bureaucracy.

“She’s right. While some of these other markets might be less lucrative today, as they continue to grow, so too will your business.”

“Uncle Michael also raised the issue about a skilled labor shortage here,” Benard said. “It looks like Amara has struggled with that. I need to be sure I can hire people with the appropriate skills. If I can’t find my employees locally, it’s going to dramatically increase costs.”

“Benard, everyone is going to tell you to go to the big markets like Nigeria, South Africa, or Kenya. There’s still money to be made there, no doubt, but it’s also tremendously competitive. Malawi, Rwanda, Mozambique — they are low-hanging fruit by comparison. Sure, you’re going to face some significant challenges — labor problems this month, infrastructure ones the next. But you’re ambitious! Don’t you want to be a leader and put back into the country what it gave you?”

Back in Nairobi

One week later in Kenya, Benard knocked on his boss’s office door. After inviting Benard in, Peter Agambu, the CEO of the company, quickly got to the point. “I’m sorry that you’re going to be leaving us to go out on your own. Have you decided where you’ll be setting up your business?”

“I met with my uncle in Nigeria and a potential partner in Malawi. There are attractive opportunities in both markets. I also spoke with a government agency in Rwanda, and they’ve set up a ‘one-stop shop’ to help new businesses get all their permits. It’s now one of the easiest places to set up a business on the whole continent. So there are many options, but it’s hard to see the clear front-runner.”

“For me it was easy,” Peter replied confidently. “Kenya was a big market, and I’m originally from Nairobi, so I knew the place well. I just had to learn about packaging.”

Peter had hired Benard right out of business school and had been his mentor ever since. In Peter’s view, entrepreneurs needed to focus on one country to succeed in the African marketplace. Africa was so culturally and politically diverse that a business that spanned multiple markets would need a huge centralized infrastructure. “Dreaming of a successful pan-African business is just that — a dream,” he’d once told Benard.

Benard recognized the challenges. There were unquestionably significant hurdles associated with expanding into multiple markets. Countries in Africa might be geographically close, but differences in language, culture, and political systems often made them seem much farther apart. Even getting from one place to another was difficult. Countries that were practically neighbors might involve several plane connections, and travel could consume an entire day.

Still, Benard believed Africa was changing and that many smaller markets that had historically been overlooked by ambitious entrepreneurs like himself were now among the most attractive.

“I bet your uncle encouraged you to strongly consider Nigeria,” Peter said. “There’s certainly a lot of excitement about its growth and potential. Even those of us outside Nigeria are now talking about it. While you might be fighting for a smaller piece of market share, it can still be very profitable to be a relatively small player in a big market.”

“That’s certainly true,” Benard replied. “But there’s no reason I can’t build a profitable business by launching in a smaller market. Of course, the trouble is, if I start off there, I’ll need to expand into other countries to gain scale, and I’ll be creating exactly the type of business you always cautioned against, because it’ll be difficult to manage.”

“My strategy was my strategy, Benard. What’s yours?”

Question: Should Benard begin his new packaging business in Nigeria or Malawi?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers