Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1426

May 14, 2014

How to Deal with a Slacker Coworker

No one likes picking up someone else’s slack. But when a colleague leaves early, misses deadlines, and doesn’t give 100% to a project, it can be difficult to determine the best course of action. Should you confront them about their behavior? Speak to your boss? Or mind your own business?

What the experts say

We’ve all worked with someone who doesn’t pull his own weight — a colleague who checks Facebook all day, takes two-hour lunch breaks, and never meets a deadline. But as irritating as it can be, you shouldn’t become the behavior police unless their slacking is materially affecting your work. “You don’t want to have the reputation of an oversensitive alarm detector,” says Allan R. Cohen, a professor of management at Babson College and author of Influence Without Authority. Susan David, the founder of the Harvard/McLean Institute of Coaching, agrees: “If your slacking coworker isn’t impacting your ability to do your job or your ability to advance in the organization, move on and focus on your own work.” But if your job is suffering because of your colleague’s behavior, it’s time to act. Here’s how to handle this tricky situation.

Put yourself in their shoes

Dealing with a colleague who isn’t giving his all can be frustrating, but don’t presume to know the root causes of his behavior — slacking doesn’t always indicate laziness. “It may be an issue at home,” says Cohen. Or it could stem from difficulties at work. Perhaps the person is struggling to understand a new assignment or to learn a new skill set. “Context matters,” says Cohen. “You don’t want to make assumptions about the other person’s motivations.” He advises doing some “exploration and inquiry” before making any moves. And that includes some introspection. But don’t spend too much time debating whether to approach them. If you wait until you’re fed up with their behavior, you’re more likely to lose your temper and look unprofessional.

Choose conversation over confrontation

If your work is affected by your colleague’s behavior, it’s time to speak up. But don’t ambush him or adopt an accusatory tone. “Approach the conversation with curiosity and compassion,” says David. “You want to show that you’re genuinely trying to solve the problem, rather than punish or make a point.” Ask how things have been going. Say, “I’ve noticed that you seem to be less engaged with this project than you used to be. Are there ways that I could help?”

Stick to the facts

Bring specific examples of the offending behavior to the conversation, and clearly explain the impact it’s had on you and other colleagues. “You want the discussion to be, ‘Here’s what happened and here’s the difference it made,’” says Cohen. For example, tell the person that her missed deadline jeopardized a client’s deal, or that her early departures required you to stay late. But keep the dialogue positive and forward-looking. Cohen suggests role-playing the conversation with someone first to get the words and tone right.

Be flexible

You may have your own idea of how best to fix the problem — but don’t get fixated on any pre-set solutions. “What is helpful is to explore different options with the individual,” says David. You should also resist the temptation to think about the situation as black-or white: you’re right and the other person is wrong. “Thinking someone is wrong is actually very depleting to us as individuals,” says David. It takes up energy, and “prevents our ability to solve anything.”

Give them a second chance

If one conversation doesn’t do the trick, try again. It may be that you weren’t direct or specific enough the first time. “You want to be able to come back to the person and say, ‘We talked about this, here’s what you said you would do, and here’s what hasn’t happened,’” says Cohen. “There might be a couple rounds of that.” If the behavior persists and it continues to negatively affect your work, it’s time to take the issue to your boss. But give your colleague a heads-up, Cohen says, both out of professional courtesy and as a further spur to change his behavior. “I believe in advance warning,” he says.

Tread carefully with your manager

Approach the boss in the same way you did the slacking colleague: with empathy, an open mind, and specific examples. If you handle the situation with grace, your manager will be impressed. If you don’t, you “start to be the person who is toxic, and who doesn’t have the emotional agility to move on,” says David. So make sure you come across as flexible and willing to help solve the problem.

Principles to remember

Do:

Keep an open mind — your colleague might have unseen reasons for slacking

Address the issue with your colleague before talking to your boss

Use specific examples to show how the behavior is affecting everyone’s work

Don’t:

Get caught up in the issue — if it’s not affecting your productivity, it’s not your problem to fix

Tell your boss without giving your colleague more than one chance to improve

Use an accusatory tone — approach the conversation with curiosity

Case Study #1: Take a friendly approach

When copywriter Katherine Childs* joined a Midwestern advertising agency, she quickly realized that Kevin* was pegged as the office slacker. The young art director took longer than others to complete assignments, turned in work using outdated software, and let his skills fall behind those of his colleagues.

Katherine, whose role included managing project workflow, saw how Kevin’s work habits hurt the entire creative team. “He was slowing down my production line,” she says. “I needed to have a certain amount of work out the door each day, but it took the team three times longer to process his files.” Though the problem had persisted for months, no one had approached Kevin about improving his workflow. “It was the elephant in the room,” Katherine says. “There was a lot of resentment, but no one was demanding he get his skills up to snuff.”

Katherine decided to talk to Kevin. She learned that he often took longer on projects not out of laziness, but because of the way he conducted research. It was clear “he wanted to be great at his job,” she says. He’d also clashed with a former boss at the agency, and cocooned himself as a result, making it easier to ignore the frustrations building around him.

Sensing Kevin would rise to the challenge, Katherine arranged for him to be given more assignments. She also quietly arranged for colleagues to train him in the skills he was missing. When broaching the subject with Kevin, she emphasized how the added effort would help him build his portfolio — and he eagerly agreed. “You often need to present such things in a way that benefits them,” she says.

In short order, Kevin was meeting deadlines and taking on more work. His colleagues noticed, and his slacker reputation was forgotten. “Once someone makes an effort — and you can see they are making an effort,” people change their perceptions, Katherine says.

Case study #2: Work around them if necessary

When Mark Berlin* was tapped to build a new direct-sales division at a major insurance company, he had to overcome a number of challenges. Chief among them was the fact that his colleague Dennis*, the head of the phone sales department, resisted doing the extra work that changing the status quo required.

Mark approached Dennis about the problem, pitching it as an opportunity to make both of their processes more efficient. “I suggested we each learn more about each other’s part of the sales funnel,” he says, but the effort went nowhere. He tried again, telling Dennis that he was hurting other teams down the line. “I tried to suggest very limited, very doable, low-hanging fruit kind of things” that could be accomplished together and build trust, says Mark. But Dennis and his team continued to be a drag on the entire division.

Ultimately, Mark had to “completely reengineer” his process to compensate for Dennis’s inefficiencies. But his efforts didn’t go unnoticed: The VP of the group “knew how hard it was to work with Dennis and appreciated what we were doing,” Mark says.

Mark’s takeaway from the experience? “Stop focusing on the slacker and start focusing on what needs to be accomplished.” There’s no right way for dealing with a colleague who isn’t giving 100 percent — “you can marginalize them, incorporate them, redirect them, or even remove them,” Mark says. But at the end of the day, “you need to know what you’re trying to get done and focus on that, not on the person.”

*Not their real names

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

Imagine you are the CEO of one of Britain’s oldest and possibly least innovative insurance companies, The Prudential. One of your better managers comes to you with the idea of setting up an internet bank. Or you are a supervisory board member of Mannesmann, a solid German engineering company, and your executive team suggests that the company bid for a mobile telephone license. Do you invest in the exciting new opportunity even though it does not fit with your existing strategy?

It depends on whom you ask.

Some experts will say that you should invest in a portfolio of new ventures as part of what McKinsey calls the “third horizon.” Using this logic, both Prudential and Mannesmann should have a go.

Other experts will argue the opposite: “stick to your existing strategy,” “don’t let yourself be distracted,” and “beware of becoming over-diversified.”

Who’s right? After more than 30 years working on corporate-level strategy issues as an academic, and advising companies as a consultant, I have learned to avoid coming down firmly on one side or the other.

In my new book, Strategy at the Corporate Level, my co-authors and I describe three logics for making these decisions: business logic, added-value logic, and capital markets logic. The latter is only relevant in the case of acquisitions or divestments. Since both of the opportunities described above are about organic growth, we can start by applying the first two logics to help leaders decide what to do.

The first logic speaks to a basic truth: companies should seek to invest in attractive businesses. An attractive business is one in a high-margin industry that is growing. In addition, the business must have or be able to create a competitive advantage. For the Pru, internet banking proved not to be a high margin industry and although it did successfully launch an internet bank, it has not had a good return on its investment. The CEO should, therefore, have been wary about this opportunity.

Owning a mobile telephone license in German, on the other hand, was likely to be a high-margin business, and, since there were few licenses for sale, the owners of a license would have a competitive advantage. Hence, the supervisory board members should have been keen to hear more about this opportunity.

Let’s look at the second logic. It makes sense for a company to own a new business if it can create more value from owning the business than other parent companies. If not, it is likely to be outcompeted by the other companies. So how does a company create more value from owning a business than others? Sometimes the parent company has some special wisdom to bring to the table or some special assets to contribute. Sometimes, the new business adds some special value to other businesses that the parent company already owns.

Unfortunately, in the cases of Mannesmann and The Prudential, neither condition appeared to exist: both new investment projects would have failed the test of the second logic.

Putting the two logics together suggests that The Prudential should have outright rejected the proposal to create Egg, the company’s internet bank, while Mannesmann should only have invested in a mobile telephone license if it anticipated changing its strategy so that it would be able to create extra value from the new business (by for example, becoming an international telecoms company) or if it anticipated selling the license after a year or two to an international telecom company (the strategy it chose).

Since this last thought involves a possible sale of a business, we need to engage the third logic, which is about the likely state of the capital markets at the time a transaction might be needed. Are the markets likely to over or under value the asset being sold? It would be reasonable for Mannesmann to expect that one of only a few mobile telephone licenses in Germany would, when the industry consolidated, attract more than a few eager bidders. So over-valuation would be more probable than under-valuation: as a potential seller of a license, Mannesman would gain.

Let’s try the three-logic analysis on an up-to-date case: whether Apple should get into the drone business. Since Microsoft and Google are buying drone businesses, I can imagine that a manager at Apple might suggest to Tim Cook that he do the same.

Is the manufacturing of drones likely to be a high margin business? Since this is a high-tech product, and there are likely to be many different segments, the answer is probably yes.

Is an Apple drone business likely to have a competitive advantage? This would depend on the specific proposal. But, although those proposing the investment will believe that they have something unique, given the range of competitors, the probability that Apple’s business will end up with an advantage is low; Cook should be wary.

Is Apple likely to create more value from owning a drone business than other companies? It’s unlikely. Even if it is possible to create exciting apps linked to drones, it is not obvious that Apple needs to make the drones to get the synergies. Other aspects of Apple’s way of managing are unlikely to constitute “wisdom” that would be of great value to a drone business. So, added value is not likely to be high and subtracted value is possible: Cook should be even more suspicious.

Finally, is the market for drone businesses over or under-valued? Given the amount of activity recently, and the rich companies that have been buying drone assets, it is likely that drone businesses are over-valued. Even capital markets logic is against this proposal. With all three logics giving red or amber signals, Cook should say no to buying into a drone business.

The three logics will often caution a management team against a new opportunity that does not fit the company’s existing strategy. But, as the Mannesmann example shows, they do not rule out all such investments. Of course, if the company does decide to go ahead, they face the challenge to decide how to structure and manage the new unit.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Should Big Companies Give Up on Innovation?

How GE Applies Lean Startup Practices

How College Experiences Shape Adult Lives, According to Gallup

High levels of well-being and engagement with work in adulthood are linked to 6 experiences in college, according to Gallup: having at least one professor who generated excitement about learning; feeling that professors cared about students as people; being encouraged by a mentor to pursue goals and dreams; working on a project that took a semester or longer to complete; having an internship or job that allowed for the application of ideas learned in the classroom; and being extremely active in extracurricular activities and organizations. Although few people report having had all six experiences, those who had the first three are 2.3 times more likely to be engaged at work and 1.9 times more likely to experience high well-being.

Beijing’s Rules for State Capitalism Are Changing

When Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy, a Chinese solar cell-maker and power-generator, missed an interest payment on its bonds in February 2014, the Chinese government didn’t intervene. As a result, Shanghai Chaori became the first Chinese company to default on servicing its debt — since 1997.

That immediately led to conjecture worldwide that China’s “Lehman Brothers moment” had arrived. In the aftermath of the Shanghai Chaori debacle, experts feared, more defaults would occur and China’s financial markets and stock markets would crash, triggering off an economic crisis — as happened in the U.S. in 2008 after Lehman Brothers went under. Nothing of the sort happened, of course.

A month later, in March 2014, when building materials company Xuzhou Zhongsen Tonghao New Board missed a coupon payment on bonds it had issued last year, the China Securities Regulatory Commission stated that “the market” would handle the problem. Sino-Capital Guaranty Trust, the bond guarantor, eventually paid investors, but Xuzhou Zhongsen became the second Chinese company to default in recent times, again sparking off speculation that China’s moment of reckoning had arrived. But it hasn’t.

In fact, the Lehman Brothers collapse is the wrong analogy to use. China has actually reached its “Dubai moments,” when the line between commercial loans and government debt must be publicly redrawn. That happened in Dubai in late 2008, when housing sales fell dramatically and real estate companies, some of them state-backed, were unable to service debt. Housing prices fell by around 60% over the next two years, and many developers went broke.

Dubai’s growth had been masterminded by its government, with state-owned banks and real estate companies shouldering most of the risk for projects that would not have been normally approved. Deal terms were often altered, so that private companies and banks would be willing to invest heavily in big projects. As a result, Dubai became one of the world’s financial capitals in 10 years’ time.

One of the problems with a state-sponsored development strategy is that it creates the widespread belief that commercial projects enjoy sovereign guarantees. That is, investors assume that if things go wrong with projects, the country’s leaders will help them by getting state-owned companies, banks, and local governments to support them. In the case of Dubai, the assumption was that oil-rich Abu Dhabi would step in if there ever was a major problem.

When Dubai’s real estate companies started collapsing, investors looked to Abu Dhabi, but the response from down the road was chilling: These were commercial loans, pointed out the Abu Dhabi government, and not guaranteed by the state. Over the next years, Abu Dhabi provided some support, but those holding commercial debt had to take significant write-downs. Real estate companies folded, investors incurred losses, and the line between commercial loans and government debt in the UAE was redrawn.

Abu Dhabi’s response at that juncture sounds pretty similar to recent statements from the China Securities Regulatory Committee in response to the two Chinese companies’ defaults. It stated that the situation “would be handled by market rules,” and in a post on Weibo, pointed out that it had “required the bond issuer, broker, and insurer to fulfill their responsibilities to investors.” Business in China is quickly realizing that the rules have been redefined, and that implicit government guarantees on commercial projects no longer exist.

Clearly, China is having its “Dubai moments.” Xuzhou Zhongsen has realized that there will be no government rescue forthcoming. Sino-Capital Guaranty Trust is confronting the reality that insuring commercial bonds is not a risk-free business. The banks have woken up to the fact that they could be stuck with non-performing liabilities. And investors are realizing there is no government guarantee on investments in China, even those associated with the state-owned banks.

What does that imply for China and the world?

One, we are, once again, witnessing the renegotiation of the rules of state capitalism in China. The relationship between the state and business, which is understood implicitly and usually not documented, is being clarified publicly. In China, that’s a pretty normal process.

Two, that process shouldn’t be equated with instability. There will be a knee-jerk tendency to link Chinese companies’ commercial problems with the financial system’s stability. However, the latter relates more to debt and cash levels, not defaults.

Three, investors would do well not to hold bank equity in China, but they shouldn’t worry about bankruptcy either. Many banks remain profitable although several smaller banks will likely need to recapitalize themselves at some point.

Four, concerns should rise about the fate of Chinese private companies, particularly those in real estate, solar, steel, cement, and manufacturing. Not only are many small groups vulnerable to downturns in the real estate market, but also, they operate on the periphery of the relationship between the state and business. When those lines shift, they could go under.

Five, don’t worry much about real estate projects in China. Even if a developer goes bust, it will be left with some construction commitments, and most projects will be put on hold or snapped up by larger players. In Dubai, five years after, the real estate market is growing so rapidly that it is generating concerns that it is over-heating.

Above all, remember that these defaults have not changed the fundamentals, which are still about manufacturing, consumer demand, and rapid urbanization in China.

May 13, 2014

The Persuasive Pressure of Peer Rankings

Introducing a new product is essentially an exercise in persuading people to change their behavior. Many companies try to tackle this challenge by making the functional benefits of the new seem so much more compelling than the old. But this approach rarely works. After all, how many of us as children enjoyed eating our vegetables just because our moms said they were better for us than desert?

But how much quicker would your attitude have adjusted if your best friend had dared you to eat them? Or if eating broccoli had suddenly become the newest craze in your fifth-grade class?

A new form of social data that harnesses the power of peer pressure is emerging as a potentially powerful way to change behavior and spur the growth of new categories of products. It works because peer pressure data goes beyond demonstrating the functions of a product to satisfy deeply powerful emotional or social needs we may not even realize we have.

Many people are aware by now, for instance, that utility companies across the U.S. have been taking advantage of peer pressure to reduce energy consumption by including charts in electricity bills showing how energy efficient you are compared to your neighbors. Companies such as Opower and My Energy have developed these data systems, and they can now point to studies that show the combination of data and social pressure reduces home energy use.

Presented in the right way, peer data can also be effective in changing consumer financial habits, such as encouraging a higher savings rate. The ING division of CapitalOne has one such application, called CompareMe, that promises to increase retirement savings rates by drawing on survey data to compare your rate to that of people with similar incomes, and to the average in your state. Putnam Investments has developed a “How Do I Compare?” feature for its 401K clients. Academic studies are showing that the peer effect works in motivating people to save more.

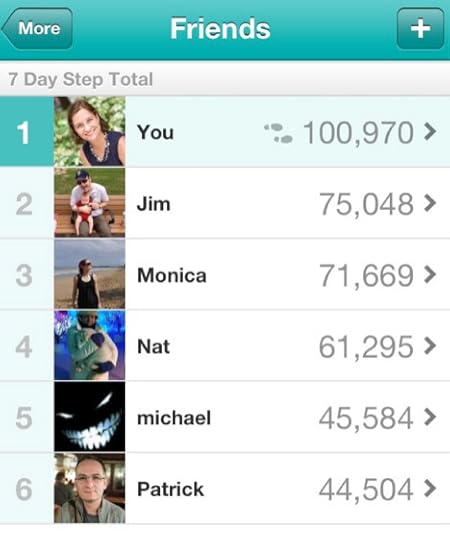

And consider what happened the first time consumers who’d bought a FitBit to track how much they exercised and slept saw the “Friends” tab on their app. Suddenly, users were invited to take part in a friendly competition to rank themselves against their friends and colleagues in weekly step counts. Here’s what you might see on (what you’d hope is) a typical week:

Competing wearables offer a variety of peer data, differentiating themselves from the mechanical activity trackers and pedometers that have long been on the market. Taken together, the power of all that peer data has helped transform a small, sleepy category into a hot product segment. Forecasts are calling for annual sales of activity trackers to balloon to more than 45 million by 2017. And this figure is almost certainly too low, considering that Apple is expected to include fitness tracking in its iWatch this fall, and some forecasters are predicting that Apple will sell more than 60 million units in the first year.

In our experience, when evaluating whether peer data can be harnessed to change the behavior of your customers, you would do well to apply these three lessons:

Know what behavior you want to change. This sounds straightforward, and in a company with a clear strategy it is. Walgreens, for instance, which has widened its mission from operating pharmacies to improving people’s overall wellness, would naturally want people to get more exercise and live healthier. So employing peer data to encourage consumers to get more exercise would certainly be desirable.

The next step, though, is not as straightforward, even in this simple case.

Identify all the compelling functional, social and emotional jobs that might motivate someone to alter that behavior. The best way to find those unmet jobs is to spend time observing current habits of consumers. Walgreens, for instance, knows that its customers are motivated by discounts (which is why it has its Balance Rewards program, which trades discounts for loyalty). So last year, it created the Steps program, which lets FitBit and Up users synch their devices to the Walgreens app, offering 20 rewards points for every mile walked (250 miles earns a $5 discount). To harness peer data, the apps let you invite Steps members that you know into your league via Twitter and Facebook.

In selecting which data to socialize, strike a balance between people’s need for privacy and their desire to share things in public. This is a tricky line to walk. Walgreens customers can share their step counts, but not their calorie counts. Sometimes the best approach is to make all the data anonymous (as the energy companies do). Other times, it might be more effective to give people control over what they share, as FitBit does (if you don’t want to share, you just don’t turn the feature on).

If this seems obvious, consider this cautionary tale: A school in Massachusetts posted student test scores, together with the first and last names of the kids who earned those scores, as a way to harness peer pressure. The idea was to encourage those at the low end to work harder. Sadly, this was a dubious premise that had not been previously tested. Even worse, the school posted all this information without even telling people they were going to do it, let alone giving them the option of not associating names with data. Not surprisingly, complaints ensued, no one was motivated to work harder, and the project was mercifully abandoned. Meanwhile, the Walgreens Steps program has been wildly successful, with 1.3 million people signing up so far, despite little advertising for it.

Finally, make the data actionable. Suppose you know, for instance, that your neighbors are using far less electricity than you are. Even if that spurs you to want to conserve, you’d still need to know how to do it. As you motivate people, you must also consider how you will follow through with steps to improve, or help their friends reach their level. Walgreens made sure that as part of its Steps program, the app and website would suggest additional ways to stay well (including suggestions of products and services that could help).

Soon just presenting peer data will no longer be enough. The social network Fitocracy goes further, assigning a human coach who creates a tailored exercise and diet program for you, then measures your headway toward your goals while also comparing your progress to your friends’. Given how new such programs are, it seems likely that innovative firms will find opportunity in devising ways to apply the power of positive peer pressure to behaviors we haven’t thought of yet.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

With Flextime, Bosses Prefer Early Birds to Night Owls

Flextime programs have never been more popular than they are today. Google allows many employees to set their own hours. At Microsoft, many employees can choose when to start their day, as long as it’s between 9am and 11am. At the “Big Four” auditing firm KPMG, some 70 percent of employees work flexible hours.

Employees love these programs because they help them avoid compromises between home and at work. Yes, there are often boundaries within which a work day must begin and end, and at least some chunk of core hours that remain common across employees. But within those constraints, workers can schedule their office hours around the various other demands on their time, giving them greater control over their lives and allowing them to accomplish more. And because employees love the programs, companies have learned to love them, too. Research shows that in general, flexible work practices lead to increased productivity, higher job satisfaction, and decreased turnover intentions.

Yet the question lingers of whether employees who take advantage of flexible work policies incur career penalties for doing so. As noted in a recent paper by Lisa Leslie and colleagues, the evidence is mixed. Their research explored a potential reason for the widely varying outcomes: managers might look upon flextime favorably when they perceive a worker is using it to achieve higher productivity, and unfavorably when they perceive it being used to accommodate personal-life demands. Leslie et al. make the case that depending on what the manager attributes the flextime use to, the employee may be either rewarded or penalized.

We looked at another possible explanation for why some flextime-using employees and not others would experience negative career outcomes. Perhaps, we hypothesized, it matters in which direction an employee shifts hours. People seem to have a tendency to celebrate early-risers. Witness the enduring popularity of aphorisms like Ben Franklin’s “early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise” or, in China, “a day’s planning should be done in the morning.” In the eyes of managers with power over careers, are employees who choose later start times stereotyped as less conscientious, and given poorer performance evaluations on average? Do the “larks” on a team hold a hidden edge over the “owls”?

We began our research by testing whether such a stereotype actually exists. We designed a laboratory experiment to discover the degree to which people made a natural implicit (that is, nonconscious) connection between words associated with morning (such as “sunrise”) or evening (such as “sunset”) and words associated with conscientiousness (such as “industriousness”). Across 120 participants, we found that on average people do make a greater natural implicit association between morning and conscientiousness.

With the general stereotype established, we went on to explore its impact in actual work settings, and on ratings provided by real supervisors. The field study we conducted tested the hypothesis that supervisor ratings of conscientiousness and performance would be associated with the timing of an employee’s work day. The hypothesis was supported. Across 149 employee-supervisor dyads, even after statistically controlling for total work hours, employees who started work earlier in the day were rated by their supervisors as more conscientious, and thus received higher performance ratings.

We conducted another laboratory experiment to test the same hypotheses in a more tightly controlled setting. We put participants in the role of being a supervisor, and asked them to rate the performance of a fictitious employee. We gave a performance profile to the supervisors, which was constant across everyone. However, in the “morning” condition we indicated that the fictional employee tended to work from 7am to 3pm, and in the “evening” condition we indicated that the fictional employee tended to work from 11am to 7pm. Everything else about the fictional employee and performance profile was identical across the conditions. Across 141 participants, we found that the research participants gave higher ratings of conscientiousness and performance to the 7am-3pm employees than to the 11am-7pm employees.

Thus, in three separate studies, we found evidence of a natural stereotype at work: Compared to people who choose to work earlier in the day, people who choose to work later in the day are implicitly assumed to be less conscientious and less effective in their jobs. But an additional finding must also be noted. In both the field study and the lab experiment, the effects were strongest for employees who had supervisors who were larks, and disappeared for employees who had supervisors who were night owls. (For those interested in further detail on the studies, our formal paper will be published later this year in the Journal of Applied Psychology.)

Of course, the implications of this research are not pretty. It seems likely that some employees are experiencing a decrement in their performance ratings that is not based on anything having to do with their actual performance. Organizations may be inadvertently punishing the employees who use flextime to start and finish working later in the day. And as accumulated poor performance ratings have detrimental effects on career advancement, this could partly explain why we often see flextime utilization having negative effects on employee careers.

The important implication is that senior managers must intervene in some way to keep supervisors from essentially punishing employees for using the very flextime policies their organizations endorse. Rather, they should be doing the opposite; if they encourage the use of flextime, they will produce the benefits noted by previous research. As with other areas of unintentional but proven bias, the advice is to increase managers’ awareness of their tendency to stereotype and why it is invalid. They must be continually reminded to recognize their cognitive tendencies and adjust for them. Managers must be especially diligent in rating the performance of employees based on objective standards, and not allowing implicit prejudices – such as their morning bias – to color their assessments.

Meanwhile, what is the individual employee to do? One message workers could take from this research is that, if they have the opportunity to use flextime, they might be better served by using it to move their schedules early in the day rather than later in the day. However, we would hesitate to recommend this, since a trend in that direction can only heighten the penalties for their colleagues whose lives outside work make the earlier hours difficult. More productively, they can raise the subject of hours and timing with their supervisors, and help make explicit the understanding that start time is immaterial.

One way or another, team leaders must come to accept that the people who use flextime to start their day late are not necessarily lazier than their early-bird colleagues. Otherwise, flextime policies that could serve both employees and employers well will become known, and avoided, as routes to dead-end careers.

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

I spoke with contributor Don Sull, who teaches strategy at MIT and the London Business School, about the tension between scholars who put sustainable competitive advantage at the center of strategy and those who argue that some industries are changing too quickly to allow for sustained performance. Here’s our edited conversation:

Who’s right — the “sustainable advantage” traditionalists or the “transient advantage” challengers?

They both have something useful to say. Let’s borrow some language from political philosophy and think in terms of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

Okay – what’s the thesis?

Start with Michael Porter. His most brilliant insight was that companies compete on a bundle of connected, mutually reinforcing activities and resources. That bundle allows the company to create value in a way that can’t be imitated. (Ikea, for example, has figured out how to get customers to pay more than you might expect for furniture that they have to assemble themselves…thus keeping IKEA’s costs low. There’s a very sophisticated, interlocking set of choices behind the advantage they’ve created.) The people who came along later and talked about competing on competencies and resources – these are all extensions of Porter’s thinking. So that’s sustainable strategy.

It’s trendy to say that sustainable competitive advantage is dead. Empirically, this is simply not true. Microsoft is in the supposedly volatile technology sector. They’ve missed almost every technological breakthrough of the past decade — and yet they earned $237 billion in operating income from 2001 to 2013 working off a strategy that was in place in the mid-1990s. It’s easy to get caught up in the hype. Sustainability still matters.

But there are plenty of businesses that appeared to be unassailable at one time that turned out to be vulnerable.

Right, which brings us to our antithesis. Another group of people had a key insight – let’s call it the opportunistic view – which is that another way to create economic value is to seize a new opportunity. Firms often use an innovative technology or a new business model to seize the new opportunity and they typically disrupt someone else’s business in the process. So this view is often associated with innovation or disruption. The core, however, is creating value by seizing new opportunities.

It’s easy for people in academia to take rhetorical shots at each other over this divide. But by and large managers understand that they need to do both things – create a difficult-to-imitate competitive position, but also seize new opportunities, find new ways to compete.

That raises a key question — how do you balance the two needs?

Here’s where we get to the synthesis. There have been several important insights. Michael Tushman and Charles O’Reilly introduced the idea of ambidexterity. It’s incredibly difficult for a company to both exploit an existing advantage and explore a new one. So it makes sense for one business unit to focus on the incumbent business and for a mostly separate unit to create a new business — with both units answering to the same corporate head. There’s a lot of good evidence that this approach works.

Another approach is to run a portfolio of businesses. GE, Johnson & Johnson, and Samsung all do this successfully. Over time, you move into new businesses and out of older ones. A good chunk of the economy runs this way. When done well, it works.

HBR ran an article by Todd Zenger recently that was interesting, claiming that you can use your mutually reinforcing system of activities and resources as a platform to catch new opportunities. He has a nice analysis of how Disney does this. It’s similar to what Chris Zook and James Allen have said about adjacencies: you find opportunities that fit your core.

Then there’s the horizons view – which is a very practical approach. It says that you focus some resources on sustaining your business, some on incremental change, and some on disruptive businesses. LEGO is a great example. The CEO has 100 people working on the core business, 20 or so on a slightly wider range of opportunities, and fewer than a dozen on innovations that could fundamentally disrupt the company’s business model.

The corporate change literature fits in here, too, though it gets away from the strategy/innovation debate. These are the people who claim that Polaroid should have seen what was coming and turned itself around. But this is incredibly difficult to do if you are running a single, focused business. I won’t say nobody’s done it. But a lot more have failed than succeeded.

The bottom line, then?

The key to success in today’s volatile markets is strategic opportunism, which allows firms to seize opportunities that are consistent with the bundle of resources and capabilities that sustain their profits.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Should Big Companies Give Up on Innovation?

How GE Applies Lean Startup Practices

Does Your Strategy Match Your Competitive Environment?

Why Twitter Needs India

Twitter’s numbers show it has a big problem. The platform is attracting fewer and fewer new users in the U.S., and its current users are abandoning it at an increasing rate. Twitter’s managers have tried to fix the problem by changing the look of Twitter profiles. Some observers suggest deeper changes to the platform: making the experience much more user friendly, developing better algorithms for surfacing interesting content, or improving search functionalities.

But what Twitter really needs is a global strategy. And this means a strategy to win in India. Without that, the bad news about Twitter will continue to pile on. Here’s why.

There are three key Internet markets in the world. First, there is China, with 618 million Internet users, about a quarter of the global online population. The Chinese will soon spend more on online purchases than consumers in the U.S., even though an average Chinese citizen only earns a ninth of what Americans do. But an American company cannot win in China, unless it engages in extensive censorship. This is why Facebook cannot compete in China, and neither can Twitter. So China is out of the picture.

Then there is the U.S. with approximately 250 million Internet users. Twitter has operated in this market since 2006, so almost everyone who wanted to try Twitter has tried it. And if they haven’t liked the service yet, it will be hard to make them do so now. On top of that, very few Americans haven’t tried the Internet yet. Even if all of them (15 years or older) went online this year, and all of them fell madly in love with Twitter, the site would add about 40 million new users. The U.S. is not going to be much help either.

Finally there is India, where in 2012 there were 150 million Internet users. This June, that number will grow to almost 250 million, about as many as in the U.S. The market is not as rich as in China or the U.S., but the number of Internet users will grow for a very long time, as there are over a billion people in India. And the Indian population loves the American social platforms: India is already the second biggest user of Facebook after the U.S., and by my calculations it will become number one this year. Facebook is already helping to make this happen. Remember WhatsApp, the acquisition Facebook made a couple of months ago for almost $19 billion? It happens to be the most popular social interaction tool in India. It’s not a coincidence that Facebook wanted to buy it to accelerate its growth there.

Meanwhile, Twitter had only 33 million users in India in 2013. And the country is nowhere close to becoming the number one user of Twitter. This is not surprising, as the company has no growth strategy in this incredibly attractive market.

So what should Twitter’s strategy in India be? The company needs to do two things. First, it needs to attract a lot of users by applying what it has learned in the U.S., where the viral process was not what brought Twitter into the mainstream and increased its numbers. TV was responsible for that. The CNN show Rick Sanchez Direct was the first to air live tweets on TV in early 2008. After the Mumbai bombings later that year, a Twitter ticket tape became a permanent fixture on CNN, and other broadcasters soon followed suit. With free 24/7 advertising on key broadcast media, it is no wonder that Twitter grew so quickly. Now, Twitter should turn that accidental success into strategy. The company should approach every conceivable broadcast medium in India to make sure that its name and its services are promoted broadly, even spending money to advertise to new Internet users in India. Remember, WhatsApp is already huge in the Indian market, and it’s used a lot by companies and politicians and other public figures. So Twitter can’t just sit there and wait for people to show up.

Second, Twitter has to keep Indian users very happy so they stay on the platform. That will require recognizing that most users in India access the Internet through their mobile phones. Indian consumers need light and fast mobile applications that don’t use up a lot of bandwidth (this is how WhatsApp become successful). Second, Twitter needs to develop additional services that alleviate some of the many information gaps in India. For example, it could develop services to aid the Indian democratic election process (currently, Google Hangouts, Facebook and WhatsApp dominate this process). Twitter could also help build a better public health information dissemination system (where it would not have many competitors). Or it could release an application to collect, aggregate and disseminate prices of produce across various markets.

All of these would help Twitter retain its Indian users for a long time. But first things first: Twitter’s management has to put India front and center of its growth strategy.

How GE Stays Young

GE is an icon of management best practices. Under CEO Jack Welch in the 1980s and 1990s, they adopted operational efficiency approaches (“Workout,” “Six Sigma,” and “Lean”) that reinforced their success and that many companies emulated. But, as befits a company that has been around for 130 years, GE is moving on. While Lean and Six Sigma continue to be important, the company is constantly looking for new ways to get better and faster for their customers. That includes learning from the outside and striving to adopt certain start-up practices, with a focus on three key management processes: (1) resource allocation that nurtures future businesses, (2) faster-cycle product development, and (3) partnering with start-ups.

Resource allocation: i ncubating a protected class of ideas.

A fundamental challenge of any firm – especially a huge global company such as GE – is how to balance nurturing tomorrow’s future businesses, with the resource demands for running and improving today’s operations. You need to think like a portfolio manager, allocating resources both to innovate in your core and for the future. Knowing that today’s operations will almost always win the lion’s share of resources, you need to consciously create a protected class of innovative ideas to invest in, even if money is tight.

For example, GE incubated an energy storage company (“Durathon”), which has gone from the lab to a $100 million business in five years. In 2009, GE’s transportation unit developed a new sodium battery for a hybrid engine for locomotives. Chief Marketing Officer Beth Comstock told me they looked to see how they could take this battery technology to new markets. After first targeting backup power for data centers, they settled on providing backup power for cell phone towers in countries with unreliable electrical grids, such as in Africa and India. Says Comstock, “You have to believe that energy storage has a big future.” It took the financial backing and technical support of GE and the support of CEO Jeff Immelt to nurture this business through numerous technical and business model changes. Marketing plays a catalyst role, providing growth funding. And after accumulating significant experience with this portfolio approach, GE is focusing today on fewer things that they’re incubating in a bigger way.

Product development: g etting closer to customers and moving faster.

Organic growth depends on discovering breakthrough ideas, leveraging technology, and getting closer to customers. As it turns out, getting the breakthrough ideas is usually the easy part. The hard part is executing the idea to build a business, which takes a process that actually works. In our current fast-paced environment of constant change, you need a product development approach that relies on many fast cycles of experimentation, reviewing prototypes early on with customers to learn what provides value, and being flexible if customer feedback suggests new directions.

As I described in a previous post, GE is working with Eric Ries, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and author recognized for pioneering the Lean Startup movement. The Lean Startup approach is enabling GE to take “Agile” and “Lean” methods, which they had been using to improve operations, and apply them to starting businesses. They have branded it “FastWorks.” And it has helped not only provide a new product development process, but a role model for a new culture based on a venture model. People in finance at GE, typically focused on return on investment and payback periods, love FastWorks because they get a better throughput of ideas.

Partnering: getting ideas from start-ups.

Leading companies have been using “Open Innovation,” collaboration, and joint ventures for many years to get a shot of adrenaline, find new markets, and get to them faster. What’s new is partnerships by large and successful companies with start-ups for joint incubation of innovative business ideas. Despite all their resources, big companies realize they can’t tackle big challenges alone. They need to tap into young, entrepreneurial companies filled with brilliant data scientists, restless tinkerers, and passionate innovators. On the other hand, start-ups benefit from the resources, customer relationships, expertise, and scale of the established companies.

GE has actively created several “ecosystems” with start-ups. For example:

In March the company formed a joint venture with Local Motors, a “co-creation company” that taps into an online community of car enthusiasts (engineers, mechanics, and industrial designers) to design new vehicles. GE intends to use Local Motors’ crowd-sourced workforce model to design new products, initially for GE Appliances.

GE has formed a partnership with Quirky, a crowd-sourced innovation platform, to invent connected products for the home: innovators submit ideas, which are voted on by Quirky’s community, and the promising ones are refined by Quirky’s designers and engineers.

Through Kaggle, another GE partner that is a community of data scientists, GE asked for algorithms to optimize airline flight paths and reduce delays – ultimately improving air travel overall.

In advanced manufacturing, GE turned to GrabCAD, asking their experts to help redesign a metal jet engine bracket with the goal of making it 30% lighter while preserving its integrity and mechanical properties like stiffness. Participants from 56 countries submitted nearly 700 bracket designs, and the winner was an engineer from Indonesia who reduced the weight of the bracket by 84%.

Finally, GE has created GE Ventures, a group in Silicon Valley that spends their time not just investing ($150 million annually), but forming technical and commercial collaborations with startups in energy, health, software, and advanced manufacturing.

GE’s current focus on innovation and on these three key management processes – which draw on the techniques and the energy of start-ups – represents the latest wave of improvement over a long and successful history. By working with and emulating start-ups, GE hopes to both grow their core offerings and disrupt their current way of doing business — and to keep an old company young. And as one of the world’s largest and most respected companies, it’s easy to imagine that other large companies will soon be following suit.

Your Sense of Moral Purity May Block You from Making Professional Connections

Research participants who imagined themselves pursuing professional connections at a party felt dirtier afterward, on average, than those who had imagined themselves merely meeting a lot of people at the party and having a good time (2.13 versus 1.43 on a five-point dirty-feelings scale), say Tiziana Casciaro of the University of Toronto, Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School, and Maryam Kouchaki of Harvard University. Moreover, people in the former group were later more likely to take a favorable view of cleaning products such as soap, toothpaste, and window cleaner. This and other experiments suggest that networking in pursuit of professional goals can harm a person’s sense of personal moral purity, the authors write in a working paper.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers