Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1423

May 20, 2014

What Data Journalists Need to Do Differently

The role of the data journalist has increased dramatically over the last decade.The past few months have seen the launch of several high-profile “data journalism” or “explanatory journalism” websites in the U.S. and the UK – such as Nate Silver’s recently relaunched and somewhat controversial FiveThirtyEight; Trinity Mirror’s ampp3d, a mobile-first site that publishes snappy viral infographics; The Upshot from The New York Times, which aims to put news into context with data; and Vox, where former Washington Post blogger Ezra Klein leads a team that provides “crucial contextual information” around news. The debates (pro and con) around these projects have brought data journalism out of its niche in digital media conferences and trade publications into the limelight.

These new media outlets have been received with both praise and criticism. Guardian journalist James Ball, who has been closely associated with the use of data for journalism – from his work with Wikileaks to the “Offshore Leaks” investigations – recently offered an interesting analysis of these developments. He points out a number of limitations in many of these data journalism projects — from the lack of transparency about their data, to the perpetuation of gender inequality among media professionals (“still a lot of white guys”), to the conspicuous absence of one of journalism’s most essential functions: the breaking of news.

But I think one of most important issues that Ball touches on is how journalists source their data. He points out that the recently launched high-profile data journalism outlets are using common data sets from established sources, such as government statistics and surveys from polling companies, rather than making an effort to find or generate their own data.

For decades, media scholars have been scrutinizing which views and voices are privileged, and which are neglected in media coverage. Decisions about who and what gets attention are intimately connected to sourcing practises: what sources journalists consider to be credible, how they prioritise them, and what they do with the information that they have sourced. While data journalism’s advocates promise a turn from opinion to evidence, anecdote to analysis, and punditry to statistical predictions, what matters is not only the nature of the source information (e.g. whether it is an interview or a database), but also where it is from, how it was produced, and what it is for. So far, my own research on data operations at major media outlets has confirmed the fact that data journalists tend to rely heavily on a small number of established sources: mainly government bodies (such as national statistical agencies or finance departments), international institutions (such as the EU, the OECD or the World Bank) and companies (such as audit or polling companies).

Why does this matter? How could things be different? And why should media organizations consider “making their own data” as journalist Javaun Moradi urged us to do back in 2011 (and as Scott Anthony argues here)? In a democracy, when the function of the media is to maintain the flow of information that facilitates the formation of public opinion, surely a multiplicity of voices, viewpoints and arguments need to be represented. However, not all members of society have the same level of access to the media, or the same resources to compete for media attention. Hence, when journalists are building their stories exclusively around existing data collected by a small number of major institutions and companies, this may exacerbate the tendency to amplify issues already considered a priority, and to downplay those that have been relegated or which aren’t on the radar screens of major institutions.

While data-driven reporting and investigations focused around existing collections of data from established organizations are of utmost importance for holding the powers that be accountable, data journalists should also strive to be critically aware of how established sources frame, shape, bias, and color different issues. Moreover, data journalists should strive to go beyond established sources to find or create their own data in order to bring about fresh reflections and insights or to bring new issues to the public’s attention.

By way of example, there are some promising finalists from this year’s Data Journalism Awards, for which I am a juror. For instance, collections of news articles can prove to be an invaluable source of data about an issue when no official monitoring or statistics exist to document it. Consider “Mediterranean sea, grave of migrants” — an investigation of unprecedented scale into the deaths of migrants seeking refuge in Europe by way of the Mediterranean Sea. One of the main sources of data for this project is a handpicked collection of news articles going back as far as 1988, maintained by one journalist. In the absence of any comprehensive official monitoring or statistics about these tragic events, a group of journalists have taken it upon themselves to build a comprehensive database of these deaths and their circumstances to support and improve policy-making around the issue of the treatment of undocumented migrants in Europe, which gestures toward another essential function that data journalism can play in society.

Social media data serves as another important source of insight into culture and society. Whereas journalists typically use social media to identify documents and human sources, as well as to communicate with others, the nonprofit investigative outlet ProPublica turns to the microblogging service Sina Weibo — otherwise known as “China’s Twitter” — to give greater insight into censorship in China by analyzing collections of images shared on the platform. ProPublica monitored 100 accounts that had been censored in the past over a period of five months, regularly checking which images posted from those accounts had been deleted. The result is an interactive application which gives “a window into the Chinese elite’s self-image and its fears, as well as a lens through which to understand China’s vast system of censorship.”

Another finalist that shows the potential of social media in emergency situations is “The Westgate attacks: A story of terrorism, citizen journalism, and Twitter”. A group of students at the University of Amsterdam used the collection of tweets around the unfolding of this catastrophe to better understand both the event itself and the role of Twitter in mediating such incidents. The result is a series of visualizations which allow the user to explore different layers of the attacks, from the people involved to the context in which it played out.

By far, the most ambitious, complex, and innovative shortlisted entry in terms of sources of data used is the Japan Broadcasting Corporation’s special program “Disaster Big Data”. This massive project gathered data (from government, business, and social media) on everything from driving records collected through car navigation systems; to location information from mobile phones; to tweets; to police vehicle sensor data; to business transactions data to better understand the impact of the major earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011. Although visualizing “big data” is a challenging task — and there is room for improvement in the visual presentation of the results — this data collection and analysis exercise of unprecedented scale in disaster situations has had an impact on how governments, businesses, and medical institutions think about disaster prevention systems in Japan and should certainly be a source of inspiration that media outlets (and governments, for that matter) can turn for data in disaster situations.

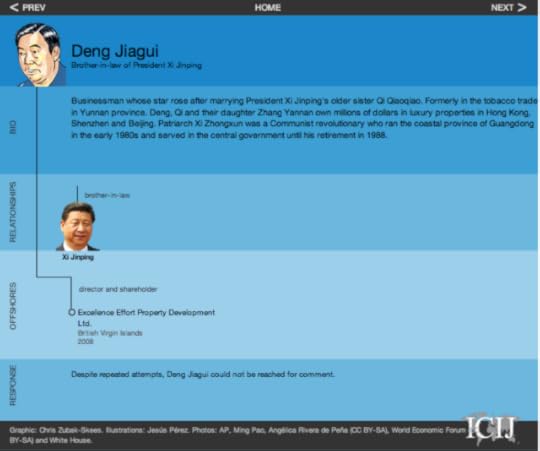

Finally, in terms of giving voice to neglected topics and groups of people, two additional stories cannot go unmentioned. The first one is the Center for Public Integrity’s “Breathless and burdened: Dying from black lung, buried by law and medicine”, a story of the denial of benefits and medical care for sick miners from central Appalachia. This topic was largely overlooked before the investigation — the only publicly available information being judges’ opinions on court cases related to benefit claims. The second is the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)’s story about the use of tax havens by China’s wealthiest and the “red nobility>,” part of a much larger project on offshore leaks.

While there are countless other entries to this year’s Data Journalism Awards that excel in terms of presentation and storytelling, hopefully some of the projects highlighted in this post will help to inspire and stimulate journalists’ imaginations concerning what counts as a source of data and how to creatively broaden the body of evidence that informs their stories.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

That Mad Men Computer, Explained by HBR in 1969

Decisions Don’t Start with Data

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

The Peril of Untrained Entry-Level Employees

Just-released findings of the Accenture 2014 College Graduate Employment Survey offer good news and bad news for employers of entry-level talent. First the bad news: most of those employers aren’t doing much to provide their new hires with the training and support they need to get their careers off to a strong start. More than half (52 percent) of respondents who graduated in 2012 and 2013 and managed to find jobs tell us they did not receive any formal training in those positions.

The good news is that, as young employees increasingly value career-relevant skills, and as awareness spreads more quickly of which employers provide good development training, there is a new opportunity for some employers to shine. By building a distinctive program for training new hires, and getting the word out about it, an organization today can gain an edge in the competition for top talent.

Why would it be that so many employers fail to provide formal training? There are all kinds of reasons. Training can be expensive and, as with many investments in highly mobile workers, the ROI is not always clear. In a time of high unemployment, it might be tempting to place the whole burden on employees to gain the skills they need, and quickly replace those who don’t. Some managers might even believe the best test of talent is to put people into unfamiliar settings and see if they can figure things out for themselves.

But bringing on new hires with the assumption that some will wash out is hardly an efficient – or responsible – way to build a great team. Usually, grads arrive in workplaces with current technical knowledge they are eager to apply, but have a lot to learn about other aspects of succeeding in their new organizations. (This is why so many first jobs feature that seeming paradox by which new employees feel unchallenged by their tasks, while their managers perceive them to be overwhelmed by the responsibilities and professional demands of the “real world.”) Employers should recognize that there are certain skills that college graduates don’t already have when they walk through the door, that are readily trainable.

Graduates themselves are increasingly attuned to the value of work-relevant training. For example, compared with past years of the survey, we find the percentage of students choosing majors based on work prospects rising substantially (75 percent of 2014 graduates say they took into account the availability of jobs in their field before deciding their major, compared to 70 percent of 2013 graduates and 65 percent of 2012 graduates). Expect the best of them also to consider the availability of training as they choose among competing job offers. Indeed, eight out of 10 graduating seniors told us that they expect formal training from their employers.

Of course, the content of entry-level training matters, too. Even employers with programs in place may need to rethink what they are designed to teach and how well they are actually serving new employees. In broad terms, you should consider adding training to:

Put key productivity tools in their hands. Most recent grads are quick to embrace solutions that allow them to work remotely – many of which involve industry-specific software they have not encountered in school. Recognize that they do not want to be constrained by the walls of the office, and become more valuable when they can work more autonomously, but that they need detailed training to be able to do their jobs on-the-go.

Build on what they already know. Take the example of social media. Given that millennial employees are truly digital natives, you might not assume – and neither will they – that you have anything to teach them about it. But they do need to be coached on what the company expects of them as its “brand ambassadors,” and now not to run afoul of communications policies.

Fill in the bigger picture. Even the greenest hire performing the most clearly defined task will do it better if she understands the business of your business. Training people early to see how their work fits into the larger scheme will lead to greater collaboration, more sharing of ideas, and deeper commitment to the mission of the organization.

Lay the groundwork for future contributions. Here, a good example might be early training in data analysis and visualization. Eventually, every profession will be touched by Big Data and the need to glean insights from consumer, customer, and employee behavior. If there is a future area of strength you know the business will need in general, plant the seeds in entry-level training, whether a trainee’s first job requires it or not.

By improving the processes for cultivating your newest and least experienced workers, you can remove much of the risk in your talent pipeline. Currently, nearly half of those who graduated within the last two years (46 percent) say they consider themselves “underemployed” and working in jobs that do not require their college degree, and more than half (56 percent) report they do not expect to stay at their first job more than two years – or that they have already left their first job. Such attrition represents an unnecessary setback for the employers who will have to go through the expensive process of finding and attracting promising young talent again. To “future proof” your business, you need to fill and maintain a pipeline of people steadily gaining experience and advancing toward leadership roles.

Finally, if you do invest to make your training of new hires better than average, be sure to figure that into your discussions with candidates. For top candidates, a company offering a strong talent development program and showing real dedication to new hires’ career advancement is very positively differentiated.

Emphasize your commitment to training in your corporate social media activity, too – and pay attention to how it is being talked about. If leaving new employees to sink or swim was ever a good option, it surely isn’t now in an age when new grads communicate their experience so richly and transparently to their networks. Neglect the training they need and want, and the word will get around quickly.

Strategy’s No Good Unless You End Up Somewhere New

Innovation isn’t always strategic, but strategy making sure as heck better be innovative. By definition, strategy is about allocating resources today to secure a better tomorrow. It is important, however, to understand the nuances and complexities of innovation as they relate to strategy. Here is my list of the four most important:

Not every industry is equally dynamic. Some industries are faster paced than others. The smart phone industry has gone through several disruptive changes in just a decade, whereas the steel industry’s technology shifts took place over a hundred-year period. Managerial “best practices” in a fast-paced industry don’t necessarily apply to everyone, everywhere.

Not all innovation is created equal. I put all innovations into two broad categories: linear innovations (which are consistent with the firm’s current business model) and non-linear innovations (not perfectly continuous with the current business model). But we need to add another layer of complexity to those categories: innovations can be incremental or radical. To illustrate, consider the Tuck School of Business, my employer. A linear, incremental innovation would be if professors from different disciplines co-taught a course. A radical (but still linear) innovation would be a major overhaul of the two-year MBA curriculum. If we were to fundamentally change our business model by offering an online MBA, that would be non-linear. Not only is there no well-understood process for creating such a program, but doing so would require Tuck to build an entirely new set of capabilities.

Execution is essential to successful innovation and strategy. Innovation is about commercializing creativity. If a firm is not making money with an idea, there is no innovation. The real challenge lies in the long, frustrating journey toward converting an idea into a fully scaled up profitable business. Moreover, this isn’t always about coming up with new products and services. We tend to think of a shiny new product offering when we picture “strategic innovation,” but that’s too limited. Apple has disrupted several industries using new business models, not new technologies. And Toyota changed the auto industry forever with a systemic process innovation (the lean production system).

Finally, innovation (and hence strategy) is not just the CEO’s job. There are two significant problems if the firm’s leader is the only one worried about strategy. First, strategy is about adapting to change – and the people at the bottom of the organization are closer to customers and the competitive environment than the CEO. Second, the company needs to selectively forget the past as it invents the future. The CEO will have the most difficulty in forgetting, especially if the CEO was responsible for creating the status quo. The people at the bottom of the organization not only are closest to the future but they have the least vested in the firm’s history.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Should Big Companies Give Up on Innovation?

How GE Applies Lean Startup Practices

Why America Is Losing Its Entrepreneurial Edge

The U.S. is one of the few nations on earth where private, for-profit business formation is seen as a quasi-heroic act. The resulting entrepreneurial culture has captured the world’s imagination and driven the nation to great prosperity. Yet now it is clearly faltering.

In a new paper that’s already generated much discussion, economists Ian Hathaway of Ennsyte Economics and Robert Litan of the Brookings Institution document four decades of “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States.” Looking at data from all fifty states and all metropolitan areas, Hathaway and Litan conclude there’s been a secular decline in business formation throughout the country, with a concurrent increase in business dissolution. The rate of business formation in 2011 was almost half of what it was in 1978, with the rate of dissolution somewhat higher than the past couple decades. When they restate this another way, the implications are clearer: “Whatever the reason, older and larger businesses are doing better relative to younger and smaller ones.” Deep, disruptive economic change is all around us, but the data indicates that the national response has not been, contrary to our myths and history, one of increased entrepreneurship.

Hathaway and Litan stay close to the data in this work and stop short of speculating about causes of this trend. So allow me. While there are numerous factors in such a massive shift away from business formation, one of the most powerful has to be the consolidation of multiple economic sectors toward a handful of firms with hegemonic power over their industry. Much of this is driven by the needs of the financial sector, which itself has consolidated massively. This paper by the Richmond Fed shows how from 1960 to 2005, the U.S. financial services sector went from 13,000 of independent banks to half that number, while the top ten banks grew from 20% market share to 60%. As of 2013, the top ten banks had 70% of the market.

Consolidation of the financial sector has led to similar dynamics in other industries. In pharmaceuticals, the largest company, Pfizer, is the result of decades of mergers. The current corporate entity is comprised of firms that used to be called: King Pharmaceuticals, Wyeth, American Cyanamid, Lederle, Pharmacia, Upjohn, Searle, SUGEN, Warner-Lambert, Parke-Davis and others. In chemicals, energy, technology, beer and more, you can see a multi-decade trend toward the consolidation of behemoths. In the guitar business, too.

How does this consolidation impact entrepreneurs? Giant firms seek the services of similarly large vendors. New, small entrants into the market will be at pains to form relationships with such firms, and the power imbalance is effectively a monopsony — sell to us at our price, on our invoice terms, or get lost. Trying to sell into a world of enormous corporate cartels is considerably more difficult than it was forty years ago, when every sector in America was smaller, more diverse and more dynamic.

Also, consider the need for new products and services in a country full of concentrated industries. When a company had dozens of potential competitors in various geographic regions, there was an incentive to innovate before the other guy does. In a concentrated market, competitors are few, and growth may come more from mergers and government lobbying than new product lines. For entrepreneurs, why start something new in such an environment? The current tech boom might serve as a counterexample, but consider that for most venture-backed companies, the ultimate exit plan is for sale of the firm to an existing behemoth, not continued independent operations.

The American entrepreneurial mythos arose in an environment that was perfect for supporting new businesses: rapid growth, technological change, constant competition, limited government intervention. We need to find ways to bring that environment back.

Wheat and Rice Cultivation Have Deep Cultural Impacts

When research subjects were asked to draw diagrams depicting their social networks, people from rice-growing and wheat-growing regions tended to respond differently: Those from rice areas drew themselves as smaller (in relation to their friends) than wheat-area people did, according to research conducted by Thomas Talhelm of the University of Virginia and reported in The Atlantic. The finding suggests that rice farming, which requires extensive social coordination, creates a culture of collectivism. Talhelm surveyed 1,162 university students in China, where rice is grown mostly in the south and wheat is raised and eaten in the north.

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Conflict happens everywhere, including in the workplace. When it does, it’s tempting to blame it on personalities. But more often than not, the real underlying cause of workplace strife is the situation itself, rather than the people involved. So, why do we automatically blame our coworkers? Chalk it up to psychology and organizational politics, which cause us to oversimplify and to draw incorrect or incomplete conclusions.

There’s a good reason why we’re inclined to jump to conclusions based on limited information. Most of us are, by nature, “cognitive misers,” a term coined by social psychologists Susan Fiske and Shelley Taylor to describe how people have a tendency to preserve cognitive resources and allocate them only to high-priority matters. And the limited supply of cognitive resources we all have is spread ever-thinner as demands on our time and attention increase.

As human beings evolved, our survival depended on being able to quickly identify and differentiate friend from foe, which meant making rapid judgments about the character and intentions of other people or tribes. Focusing on people rather than situations is faster and simpler, and focusing on a few attributes of people, rather than on their complicated entirety, is an additional temptation.

Stereotypes are shortcuts that preserve cognitive resources and enable faster interpretations, albeit ones that may be inaccurate, unfair, and harmful. While few people would feel comfortable openly describing one another based on racial, ethnic, or gender stereotypes, most people have no reservations about explaining others’ behavior with a personality typology like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (“She’s such an ‘INTJ’”), Enneagram, or Color Code (“He’s such an 8: Challenger”).

Personality or style typologies like Myers-Briggs, Enneagram, the DISC Assessment, Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument, Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument and others have been criticized by academic psychologists for their unproven or debatable reliability and validity. Yet, according to the Association of Test Publishers, the Society for Human Resources, and the publisher of the Myers-Briggs, these assessments are still administered millions of times per year for personnel selection, executive coaching, team building and conflict resolution. As Annie Murphy Paul argues in her insightful book, The Cult Of Personality, these horoscope-like personality classifications at best capture only a small amount of variance in behavior, and in combination only explain tangential aspects of adversarial dynamics in the workplace. Yet, they’re frequently relied upon for the purposes of conflict resolution. An ENTP and an ISTJ might have a hard time working together. Then again, so might a Capricorn and a Sagittarius. So might any of us.

The real reasons for conflict are a lot harder to raise — and resolve — because they are likely to be complex, nuanced, and politically sensitive. For example, people’s interests may truly be opposed; roles and levels of authority may not be correctly defined or delineated; there may be real incentives to compete rather than to collaborate; and there may be little to no accountability or transparency about what people do or say.

When two coworkers create a safe and imaginary set of explanations for their conflict (“My coworker is a micromanager,” or “My coworker doesn’t care whether errors are corrected”), neither of them has to challenge or incur the wrath of others in the organization. It’s much easier for them to imagine that they’ll work better together if they simply understand each other’s personality (or personality type) than it is to realize that they would have to come together to, for example, request that their boss stop pitting them against one another, or to request that HR match rhetoric about collaboration with real incentives to work together. Or, perhaps the conflict is due to someone on the team simply not doing his or her job, in which case talking about personality as being the cause of conflict is a dangerous distraction from the real issue. Personality typologies may even provide rationalizations, for example, if someone says “I am a spontaneous type and that’s why I have a tough time with deadlines.” Spontaneous or not, they still have to do their work well and on time if they want to minimize conflict with their colleagues or customers.

Focusing too much on either hypothetical or irrelevant causes of conflict may be easy and fun in the short term, but it creates the risk over the long term that the underlying causes of conflict will never be addressed or fixed.

So what’s the right approach to resolving conflicts at work?

First, look at the situational dynamics that are causing or worsening conflict, which are likely to be complex and multifaceted. Consider how conflict resolution might necessitate the involvement, support, and commitment of other individuals or teams in the organization. For example, if roles are poorly defined, a boss might need to clarify who is responsible for what. If incentives reward individual rather than team performance, Human Resources can be called in to help better align incentives with organizational goals.

Then, think about how both parties might have to take risks to change the status quo: systems, roles, processes, incentives or levels of authority. To do this, ask and discuss the question: “If it weren’t the two of us in these roles, what conflict might be expected of any two people in these roles?” For example, if I’m a trader and you’re in risk management, there is a fundamental difference in our perspectives and priorities. Let’s talk about how to optimize the competing goals of profits versus safety, and risk versus return, instead of first talking about your conservative, data-driven approach to decision making and contrasting it to my more risk-seeking intuitive style.

Finally, if you or others feel you must use personality testing as part of conflict resolution, consider using non-categorical, well-validated personality assessments such as the Hogan Personality Inventory or the IPIP-NEO Assessment of the “Big Five” Personality dimensions (which can be taken for free here). These tests, which have ample peer-reviewed, psychometric evidence to support their reliability and validity, better explain variance in behavior than do categorical assessments like the Myers-Briggs, and therefore can better explain why conflicts may have unfolded the way they have. And unlike the Myers-Briggs which provides an “I’m OK, you’re OK”-type report, the Hogan Personality Inventory and the NEO are likely to identify some hard-hitting development themes for almost anyone brave enough to take them, for example telling you that you are set in your ways, likely to anger easily, and take criticism too personally. While often hard to take, this is precisely the kind of feedback that can help build self-awareness and mutual awareness among two or more people engaged in a conflict.

As a colleague of mine likes to say, “treatment without diagnosis is malpractice.” Treatment with superficial or inaccurate diagnostic categories can be just as bad. To solve conflict, you need to find, diagnose and address the real causes and effects — not imaginary ones.

May 19, 2014

An Introduction to Data-Driven Decisions for Managers Who Don’t Like Math

Not a week goes by without us publishing something here at HBR about the value of data in business. Big data, small data, internal, external, experimental, observational — everywhere we look, information is being captured, quantified, and used to make business decisions.

Not everyone needs to become a quant. But it is worth brushing up on the basics of quantitative analysis, so as to understand and improve the use of data in your business. We’ve created a reading list of the best HBR articles on the subject to get you started.

Why data matters

Companies are vacuuming up data to make better decisions about everything from product development and advertising to hiring. In their 2012 feature on big data, Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson describe the opportunity and report that “companies in the top third of their industry in the use of data-driven decision making were, on average, 5% more productive and 6% more profitable than their competitors” even after accounting for several confounding factors.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise, argues McAfee in a pair of recent posts. Data and algorithms have a tendency to outperform human intuition in a wide variety of circumstances.

Picking the right metrics

“There is a difference between numbers and numbers that matter,” write Jeff Bladt and Bob Filbin in a post from last year. One of the most important steps in beginning to make decisions with data is to pick the right metrics. Good metrics “are consistent, cheap, and quick to collect.” But most importantly, they must capture something your business cares about.

The difference between analytics and experiments

Data can come from all manner of sources, including customer surveys, business intelligence software, and third party research. One of the most important distinctions to make is between analytics and experiments. The former provides data on what is happening in a business, the latter actively tests out different approaches with different consumer or employee segments and measures the difference in response. For more on what analytics can be used for, read Thomas Davenport’s 2013 HBR article Analytics 3.0. For more on running successful experiments, try these two articles.

Ask the right questions of data

Though statistical analysis will be left to quantitative analysts, managers have a critical role to play in the beginning and end of the process, framing the question and analyzing the results. In the 2013 article Keep Up with Your Quants, Thomas Davenport lists six questions that managers should ask to push back on their analysts’ conclusions:

1. What was the source of your data?

2. How well do the sample data represent the population?

3. Does your data distribution include outliers? How did they affect the results?

4. What assumptions are behind your analysis? Might certain conditions render your assumptions and your model invalid?

5. Why did you decide on that particular analytical approach? What alternatives did you consider?

6. How likely is it that the independent variables are actually causing the changes in the dependent variable? Might other analyses establish causality more clearly?

The article offers a primer on how to frame data questions as well. For a shorter walk-through on how to think like a data scientist, try this post on applying very basic statistical reasoning to the everyday example of meetings.

Correlation vs. cause-and-effect

The phrase “correlation is not causation” is commonplace, but figuring out just what it implies in the business context isn’t so easy. When is it reasonable to act on the basis of a correlation discovered in a company’s data?

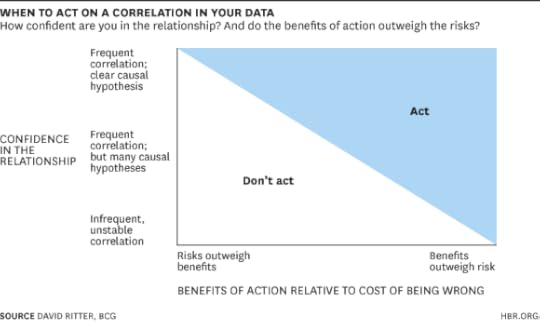

In this post, Thomas Redman examines causal reasoning in the context of his own diet, to give a sense of how cause-and-effect works. And BCG’s David Ritter offers a framework for deciding when correlation is enough to act on here:

The more frequent the correlation, and the lower the risk of being wrong, the more it makes sense to act based on that correlation.

Know the basics of data visualization

Rule #1: No more crap circles. To decide how to best display your data, ask these five questions. Make sure to browse some of the best infographics of all time. And before you present your data to the board, consult this series on persuading with data. (Don’t forget to tell a good story.)

Learn statistics

A couple of years ago, Davenport declared in HBR that data scientists have the sexiest job of the 21st century. His advice to the rest of us? If you don’t have a passing understanding of introductory statistics, it might be worth a refresher.

That doesn’t have to mean going back to school, as Nate Silver advises in an interview with HBR. “The best training is almost always going to be hands on training,” he says. “Getting your hands dirty with the data set is, I think, far and away better than spending too much time doing reading and so forth.”

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How Data Visualization Answered One of Retail’s Most Vexing Questions

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

When “Scratch Your Own Itch” Is Dangerous Advice for Entrepreneurs

“Scratch your own itch,” is one of the most influential aphorisms in entrepreneurship. It lies behind successful product companies like Apple, Dropbox, and Kickstarter, but it can also lead entrepreneurs predictably to failure.

This approach to entrepreneurship increases your market knowledge: as a potential user, you know the problem, how you’re currently trying to solve it, and what dimensions of performance matter. And you can use this knowledge to avoid much of the market risk in building a new product. But scratching your own itch will lead you astray if you are a high-performance consumer whose problem stems from existing products not performing well enough – in other words, if the itch results from a performance gap.

Building a company around a better-performing product means competing head-on with a powerful incumbent that has the information, resources, and motivation to kill your business. Clayton Christensen first documented this phenomenon in his study of the disk drive industry, and found that new companies targeting existing customers succeeded 6% of the time, while new companies that targeted non-consumers succeeded 37% of the time. Even with a technological head start, wining the fight for incumbents’ most profitable customers is nearly impossible.

An itch can result from two very different sources: existing products lacking the performance you need, or a lack of products to solve your problem. In the former case, you already buy products and will pay more if they perform better along well-defined dimensions. In the latter, products don’t exist at all or you lack access to very expensive, centralized products and so make due with a cobbled-together solution or nothing at all. It’s the difference between needing another feature from your Salesforce-based CRM system and spending hours and hours tracking information in Excel because you can’t justify the expense of implementing Salesforce in the first place.

Consider, for example, two successful companies that at first seem to result from performance-gaps: Dropbox and Oculus VR.

Dropbox began with the difficulty of backing up and sharing important documents, and developed a system that was easier to use than carrying around a USB stick and less expensive than paid services like Carbonite. Dropbox didn’t just set out to offer superior performance; it targeted an entirely new customer set that wasn’t using existing solutions, with a business model that would undermine the incumbents’ most profitable customers. Dropbox’s business model made head-to-head competition with incumbents unlikely, since the Carbonite’s of the world sensed that they would earn less off of their best customers if they offered a free service.

Oculus created a virtual reality headset designed to be a hardware platform, primarily focusing on gaming – and recently sold to Facebook for $2.3 billion. Although envisioned as a platform that would enable any kind of virtual reality application, Oculus was created with hardcore gamers in mind. Unlike Dropbox, Oculus’s first customers would have been the most profitable customers of existing game platforms, giving incumbents like X-Box and PlayStation a strong incentive to emulate Oculus’s technology to retain their best customers and make them even more profitable.

Oculus, of course, was wildly successful. But only because Facebook felt that, despite being developed with existing customers in mind, the technology would be appealing to non-gamers for the purpose of messaging and social networking. Facebook bought Oculus to rescue it from a flawed strategy by shifting its focus from high-end customers to non-consumers.

Oculus’s founder set out to scratch his own itch by creating a new gaming platform, one that targeted a customer set of hardcore gamers who were already served by incumbent firms. Dropbox’s founder scratched his own itch by creating a product aimed at a new set of customers, who weren’t being served by incumbents. The difference matters greatly in terms of a company’s competitive position.

Before founding a business around a problem you face, first understand whether that problem is a performance gap or a product void, by asking the following questions:

How am I currently solving this problem?

Do other products exist that solve this problem?

Do they provide good enough performance, or is there still a performance gap?

Are they too expensive to use? Are they centralized and do they require special expertise?

Would this product make any incumbent’s existing customers more profitable?

Ultimately, if your product would make an incumbent’s best customers more profitable, you should steer clear: Facebook won’t always be there to bail you out.

A Simple Tool for Making Better Forecasts

One of the most basic keys to good decision-making is accurate forecasting of the future. In order to bring about the best outcomes, a company must correctly anticipate the most likely future states of the world. Yet despite its importance, companies not only routinely make basic forecasting mistakes, they also shoot themselves in the foot by applying procedures that make accurate predictions harder to achieve.

The future, to state the obvious, is uncertain. We may want to know precisely what the future will hold, but we realize that the best we can settle for is having some idea of the range of possible outcomes and how likely these outcomes are. Yet most companies seem to ignore this fact and ask employees to provide point predictions of what will happen—the exact price of a stock, the precise level of growth of a country’s GDP next year, or the estimated return, to the dollar, on an investment.

These precise, single-value estimates are poor decision aids. Suppose the forecaster’s best guess is that a project will be completed within a year, but the second most likely outcome is that, if the judge denies a zoning appeal, the project will take more than two years to complete. No single point prediction can provide the decision maker with the essential information about what to prepare for.

One way to counteract this problem is to ask for range forecasts, or confidence intervals. These ranges consist of two points, representing the reasonable “best case” and “worst case” scenarios. Range forecasts are more useful than point predictions. But they run the risk of, on one hand, being so wide, including everything from total catastrophe to glorious triumph, that they are not very informative. On the other hand, it happens even more often that the range is drawn too narrowly, missing the true value. Forecasters often struggle with this accuracy-informativeness tradeoff, and attempts to balance the two criteria typically result in overconfident forecasts. Research on these types of forecasts finds that 90% confidence intervals, which, by definition, should hit the mark 9 out of 10 times, tend to include the correct answer less than 50% of the time.

In our research, we looked for a forecasting approach that could provide both accuracy and informativeness: one that will protect the forecaster from the known traps of overconfidence and biased forecasting, and provide an informative forecast that includes all plausible future scenarios as well as an assessment of how likely each one of them is. We have developed a method called SPIES (Subjective Probability Interval EStimates), which computes a range forecasts from a series of probability estimates, rather than from two point predictions.

You can experiment with a version of SPIES aimed at forecasting temperature below:

The rationale for calculating range forecasts this way is based on the finding that, while people tend to be overconfident in forecasting confidence intervals, they are much more accurate in evaluating other people’s confidence intervals and estimating the likelihood that a particular forecast will be accurate. So the SPIES method divides the entire range into intervals, or bins, and asks the forecaster to consider all of these bins and estimate the likelihood that each one of them will include the true value. From these likelihood estimates, SPIES can estimate a range forecast of any confidence level the decision maker prefers.

The SPIES method provides a number of distinct advantages for forecasters and decision makers. First, it simply produces better range forecasts. Our studies consistently show that forecasts made using SPIES hit the correct answer more frequently than other forecasting methods. For example, in one study, participants used both confidence intervals and SPIES to estimate temperatures. While their 90% confidence intervals included the correct answer about 30% of the time, the hit-rate of intervals produced by the SPIES method was just shy of 74%. Another study included a quiz of the dates in which various historical events occurred. Participants who used 90% confidence intervals answered 54% of the questions correctly. The confidence intervals SPIES produced, however, resulted in accurate estimates 77% of the time. By making the forecaster consider the entire range of possibilities, SPIES minimizes the chance that certain values or scenarios will be overlooked. Second, this method gives the decision maker a sense of the full probability distribution, making it a rich, dynamic, planning tool. The decision maker now knows the best- and worst-case scenarios, but also how likely each scenario is, and the likelihood that the estimated value, be it production rate, costs or project completion time, will fall above or below an important threshold.

How can you use SPIES to your advantage? Consider a manager who must decide how many units to produce. A forecast made with SPIES estimates the odds of all possible scenarios and thus assists the manager in mitigating the different risks of over- or under-producing. Similarly, a contractor could use SPIES to forecast the likelihood of finishing current work in time to take on more work, as well as the likelihood of progress on current projects slowing down, making any additional work a strain on resources.

With so many strategic decisions for firms depending on predicting the future, forecasting accurately is enormously important. While traditional forecasting methods tend to produce poor results, we are happy to report real progress helping people make better forecasts. The SPIES method represents a big step forward, integrating insights from the latest research results on the psychology of forecasting. Managers who receive richer and more unbiased information make better decisions, and SPIES can provide it.

You can use the SPIES tool below to try forecasts in the context of your own business:

Mixing Business and Social Good Is Not A New Idea

More and more business schools are building programs to support students who want to do business while doing good. In addition, companies are rebuilding their recruiting processes to attract top talent that cares less about financial rewards and more about social impact. It seems like every day I see a new blog post from a thinker or business leader discussing how to innovate a process or build a whole new business model to make a profit and a difference. One key theme in these conversations, even if unspoken, is that this is a new, unexplored territory for both entrepreneurs and established businesses.

It may be less explored in our post-1980’s, “greed is good” world, but it’s hardly new.

Business history is filled with stories of businesspeople who were determined to create a better life for their employees or their community. Less than 100 years ago, chocolatier Milton Hershey transferred his majority ownership of the Hershey Chocolate Company to the Milton Hershey School Trust, which provides education and homes to children from low-income families or with social needs. The Trust and the School still maintain the majority of voting shares in the company to this day. Instead of a company owning or funding a nonprofit foundation, Hershey built a model where the nonprofit essentially owns the company.

A few decades earlier, in Ireland, Arthur Guinness and the Guinness family began an ambitious employee welfare program unparalleled by any other business at the time. Even in the 1860s, the company provided pensions for employees, their widows and children, with free meals given every week to the sons of pensioners and widows in order to encourage the children to attend school. The company worked to improve the living conditions and tuberculosisoutbreak suffered by its employees, their families and the famine-ravished Dublin community. The company hired physician Sir John Lumsden and funded a two-month study of employees’ families before eventually building a program that included sanitary housing for employees, as well as nutrition and cooking classes, all aimed at not just improving employee health and productivity, but influencing the entire city to make the needed changes to improve overall health in the city of Dublin.

If you look even further into history, thousands of years earlier, you can even find this urge to care for the poor built into ancient societies and religions. In the ancient Hebrew tradition for example, farmers and landowners were encouraged to adhere to a principle called gleaning, outlined in the books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus in the Torah. According to the principle, farmers left the corners of their fields unharvested, in order to provide for the poor, widows, or wanderers who could come and harvest the remains. While the specifics around gleaning changed with time and cultures, all variations promoted the idea that owning an asset also carried with it the responsibility to care for those without such means. Thus, built into the business model of harvesting was a system for providing for the needs of the community.

These are just a few of the historical examples that give the lie to the notion that all a business exists to do is create a profit for its owners. There’s an old saying that “history doesn’t repeat itself but sometimes it rhymes.” Today’s upsurge of enthusiasm about creating shared value – not just shareholder value – is a great example of this phenomenon. Let’s not forget our history of kindness again.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers