Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1419

May 29, 2014

How to Break Up with Your Mentor

Having a great mentor can do wonders for your professional development and career. But even the best mentoring relationships can run their course or become ineffective. How do you know when it’s time to move on? And what’s the best way to end the relationship without burning bridges?

What the Experts Say

“A good mentoring relationship is as long as it should be and no longer,” says Jodi Glickman, author of Great on the Job. If you are no longer learning from your mentor or the chemistry is simply not there, “there’s no point in prolonging it.” You do yourself and your mentor a disservice if you stay in a relationship that isn’t meeting your needs. “If in order to grow, it’s necessary to move on,” don’t hesitate to break it off, says Kathy Kram, the Shipley Professor in Management at the Boston University School of Management and coauthor of the forthcoming Strategic Relationships at Work. Here’s how to end things graciously.

Take stock of your needs and goals

Ask yourself what value you’ve gained from your mentor, what guidance and support you feel you aren’t getting, and what you want going forward. With introspection, you can figure out “what’s missing in the relationship and whether there is an opportunity to reshape it in some way,” says Kram. You may decide that your mentor’s skill set doesn’t align with where your career is heading. Or you may want a mentor with whom you have a better rapport, or who has more time to offer. The exercise may even surprise you. You could discover that you haven’t been taking full advantage of your mentor’s expertise, for example.

Consider giving your mentor a second chance

Don’t assume that your mentor has a crystal ball. If you aren’t getting the guidance you want, it may be because you haven’t articulated your expectations and needs. “People don’t realize they need to educate their mentors, too,” says Kram. You should spell out “what you are striving toward and how you think your mentor can help.” Consider approaching him to make your needs clear, saying, ‘These are the challenges I’m now facing and this is the kind of advice I’m hoping to get.’ That said, “if you feel like you’ve both received and given value but going forward it’s the law of diminishing returns, it’s time to end it,” says Glickman.

Don’t draw it out

If you decide the relationship isn’t working, act on it quickly. “You don’t want to waste your time, or frankly theirs,” says Glickman. If your mentor-mentee arrangement is more formal, it’s often advisable to arrange a time to discuss the issue face-to-face. But not everyone has to break up over lunch. Depending on the nature of your previous interactions, parting ways could involve a note or a telephone call, or be as simple as letting the relationship fade away. But however you do it, don’t drag out your interactions with him if you don’t plan on investing in the relationship and taking it seriously.

Disengage with gratitude

“Gratitude is the key to leaving gracefully,” says Kram. Start the separation conversation by thanking your mentor for all of her time and effort. Detail what you’ve learned in the course of the relationship and how those skills will help your career in the future. “Speak in terms of how your needs have changed rather than in how your mentor is not doing x,y, and z for you,” says Kram. “Maintain the focus on yourself and your reasons for wanting to move on.” By keeping it positive, you’ll leave open the possibility of future collaborations.

Be transparent and direct

Be as honest and transparent as possible about why your future plans necessitate a shift, says Glickman. You might say, “Given my change in focus, I wonder if getting together regularly is the best use of your time.” Don’t worry too much that they will be upset or offended. “Prolonging a relationship out of respect for them doesn’t help them,” says Glickman. “They likely have plenty of other things they can do.” If your mentor does react negatively, “listen well, give him the opportunity to share his perspective, and if you don’t agree, just thank him for having shared it” and move on, says Kram.

Keep the door open

In today’s workplace, connections are more important than ever, and you’re likely to come across your former mentor at some point in the future. Since you want to part ways with your professional reputation intact, make every effort not to burn bridges. Be sure to offer her any assistance she might need in the future so you can return the kindness and help she has given you. “You never know when you are going to encounter this person again, whether as a boss, a subordinate, or a peer,” says Kram. “And you never know if you might need them again.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Consider whether the relationship can be recharged — give your mentor an opportunity to adapt with you

Emphasize your appreciation and thanks above all else

Describe what you’ve learned from them and how those skills will help your career going forward

Don’t:

Stay in the relationship out of obligation — you’ll only waste your time and theirs

Focus on the relationship’s shortcomings — emphasize the positive

Burn bridges — you never know when you might encounter them again

Case Study #1: Establish expectations early on

When Debby Carreau was promoted from the operations side of a multibillion-dollar hospitality company to a high-level HR position, her boss assigned her a mentor to help with the transition. For the first several months, Debby and her mentor (we’ll call him Jeff) had a productive and positive rapport. He was very helpful with developing Debby’s strategy skills. “He taught me to step back and look at the bigger picture,” she says.

One day, as Debby was conducting a sound check for a presentation at a major conference, Jeff walked in and requested a run-through. He proceeded to dissect her talk and suggested a number of changes. “I suspect his intentions were good, but I felt blindsided,” Debby says. She considered his input, but did not incorporate many of his suggestions. Following her well-received speech, she heard from a colleague that Jeff was upset, telling several people that he “didn’t know why he bothered giving her advice if she isn’t going to listen to it.” At that point, “I knew this relationship was not going to work. While I valued his input and feedback, I was not always going to act on it,” Debby says.

Debby approached Jeff the next morning. “I focused on what I appreciated specifically, thanking him for his insight into strategy and his best-practice sharing,” she says. But after confirming that he had been disappointed with her failure to take his advice, Debby politely pushed back, saying that while she valued his opinion, she wasn’t under the impression she was obligated to follow his directions.

They left the conference on good terms, but their formal mentoring relationship petered out not long after. Her lesson? It’s critical for mentors and mentees to establish “on the front end what the expectations are and how you are going to engage.”

Case Study #2: Exit gracefully

Chris Hoffman, a marketing and brand strategy consultant in Colorado Springs, knew he owed much of his professional development to his boss, a marketing executive we’ll call Frank. Chris had sought him out as a mentor, taking him to coffee, buying him lunch, and picking his brain about marketing and problem-solving strategies. “I really learned so much from him,” Chris says.

But after working at Frank’s agency for four years, Chris began to feel that he’d outgrown his position — and his mentee relationship with Frank. He had learned a great deal, but other frustrations — Frank’s unnecessary distance from the day-to-day operations, his disinterest in feedback, and their value differences — made Chris feel increasingly disillusioned. “It was time for me to pursue my own endeavors and break out on my own,” Chris says.

His departure from the agency provided a natural transition point. During their final conversations, Chris emphasized how grateful he was for Frank having “invested in me with his time and his knowledge.” Chris recapped the great things they’d been able to accomplish, and “made a conscious effort to come across as humble instead of focusing on my frustrations.”

Frank offered to continue mentoring Chris after he left the agency, but Chris politely deflected the requests. “I told him truthfully that I had some new projects that I needed to spend 100 percent of my time on,” he says. He also stopped reaching out to Frank, and over time the relationship settled into an amicable friendship. “I see him from time to time and it’s not awkward at all,” Chris says. “I’ve actually done some contract work for his company since moving on, so that’s a win for me.”

The Origins of Discovery-Driven Planning

When HBR asked us to write about the origins of discovery-driven planning, we had to laugh. It all started back in the mid-1990s, with Rita’s “flops” file – her collection of projects that had lost their parent company at least US$50 million. (Perfume from the people who make cheap plastic pens, anyone? How about vegetable-flavored Jello?)

As we studied those failures, a pattern became clear to us. The projects were all being planned as if they were incremental innovations in a predictable setting: The assumption was that the organizations launching them had a rich platform of experience and knowledge upon which to draw. The venture leaders made critical assumptions which were never tested. The funding was often significant, and approved and handed out all at once. Leaders were personally committed to the particular strategy the ventures were pursuing. And it took a long time and a lot of money before they realized that the project had been barreling along, burning tons of cash, but heading for disaster.

Clearly, a new approach to planning was needed – one better suited to high potential projects whose prospects are uncertain at the start. In Mac’s entrepreneurship classes at Wharton, many of the elements of discovery-driven planning were already emerging from work he had done on milestone planning with Zenas Block at NYU. He stressed the importance of having a revenue model (as well as a cost model), of documenting and testing assumptions, and of moving ventures through a series of milestones, rather than trying to plan them all at once. It was on a business trip to Zurich, of all places, that all these ideas came together in a concept for a planning toolkit that would be suitable for new venture leaders.

So, what was different about DDP than conventional planning methods? First, we forced venture leaders to articulate right up front what success for their businesses would have to look like to make it worth the risk and justify the resources and the effort. Then, we’d ask them to do what Mac asks his entrepreneurship students to do, which was to benchmark the key revenue and cost metrics in their business against the market and against firms offering the most comparable products. Next, we’d force them to articulate the specific operational activities their business needed to carry out in very concrete terms. Mac always liked to ask his students to specify how they were going to get their “first five sales,” rather than put grandiose projected revenue numbers in their spreadsheets. As the venture teams were specifying these operations they thought would underpin their businesses, they’d have to be making assumptions, and in our planning model, we’d insist that they write them down. And finally, we’d drive the whole plan through a series of milestones (which we’ve subsequently renamed checkpoints) which represented the points in time at which the most sensitive assumptions could be tested. We’d ask our venture teams to re-evaluate their assumptions at these checkpoints, ahead of major investments. At that point, they could stop and disengage, redirect to a reconfigured plan or continue. We challenged venture teams to spend their imagination to avoid spending money – to use their creativity to learn as much as possible as cheaply as possible, reflecting the parsimony Mac demands in his entrepreneurship classes.

The worlds of strategy and innovation have gotten much closer to one another since the publication of Discovery Driven Planning, and increasingly entrepreneurial tools are used inside established corporations. As Rita argues in her book The End of Competitive Advantage, any such competitive advantage is eroding ever-more quickly, which means that firms need to create a pipeline of advantages to replace those that have been competed away. That in turn implies that innovation – and innovative strategy — needs to be a systematic, ongoing process with a set of tools and processes that let firms achieve innovative results reliably or abandon them inexpensively. The following enhancements to DDP methodology may be valuable for firms that need to continuously innovate:

Firms will need to generate assumptions about who likely future competitors will be and design checkpoints to test whether and when brand new competitors are emerging, thus better anticipating disruption.

They’ll need to make assumptions about when competitive attacks and erosion of profits will begin, and design checkpoints as indicators that this is happening so that the next advantage stage can be launched at the optimal time.

Given the increasing rate of change, it doesn’t make sense to think past the next four checkpoints. This should move the conversation from “are we deploying enough (i.e., a lot of) money to try to build a sustainable advantage?” to “Do we have just enough money to get through the next three checkpoints?”

To speed up the “demolition” of ventures that start off seeming to be good ideas but turn out to be flawed, we need to creatively design inexpensive, roughly right checkpoints that cheaply and quickly probe whether key assumptions are wrong.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Boards Can Innovate

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Gratitude Can Make You More Patient for Future Rewards

The conventional advice for overcoming our tendency to seek immediate gratification and discount future rewards is to increase our patience by suppressing emotions, but one emotion—gratitude—appears to enhance patience, says a team led by David DeSteno of Northeastern University. In an experiment, people who were induced to feel grateful were subsequently better able to resist instant gratification: In order to forgo $85 three months in the future, they required, on average, $63 immediately, whereas those in neutral or generally happy emotional states required just $55. Because gratitude can prompt kindness from others, the patience-enhancing effect of gratitude may have evolved as a way to allow people to wait for those kindly acts, the researchers suggest.

Unemployment Is About to Fall a Lot Faster than Predicted

The recovery from the Great Recession has been slow and painful, especially when it comes to jobs. The unemployment rate, which peaked at 10% in October 2009, is still an unpleasantly high 6.3% (compared with 4.4% before the recession), and many economists are saying it won’t go much lower anytime soon. The Federal Reserve’s forecast (made in December 2013) is for a rate of 6.3% at the end of this year, with not much chance of dropping below 5.5% before the end of 2016. Others are even gloomier: Trading Economics projects unemployment rates above 6% for the next couple of decades.

But what if all this gloominess is unwarranted? Using an alternative model for projecting job growth, we see an entirely different scenario, one in which the U.S. unemployment rate will fall below 5% by no later than the middle of next year. This would of course have a profound effect on business and the overall economy.

Unemployment forecasts are generally based on past trends — a reasonable if not infallible approach. But the assumptions being used may be wrong this time around. In past recessions, small businesses fueled early job growth and drove a predictable pattern that is currently used to estimate unemployment. During the current economic recovery, however, the largest of businesses added to their payrolls first, while small businesses have significantly underperformed in job growth. This has essentially created an inverse trend.

The typical trend in economic recoveries is driven by a process known as “cyclical upgrading,” where employment transfers to high-paying industries during booms and low wage jobs during recessions. Small businesses have a disproportionate number of low-wage jobs and that often leads job seekers toward those companies during recessions, which is what then fuels a rebound in employment. In previous recessions, small businesses were responsible for the bulk of new hires during a recovery. (This makes sense because small businesses, with their lower wages, employ more than half the workforce and create a full two-thirds of the new jobs in the United States.) Then, toward the end of most recoveries, as larger businesses add higher-wage jobs, unemployment continues to drop, but at a slower pace given that large businesses have fewer jobs available. This pattern is apparent after a quick glance at unemployment trends over the past century: the unemployment rate drops quickly after its peak, and then the drop becomes less steep.

The current economic cycle, however, is different. During this recession, the recovery started with big businesses, spurred initially by government bailouts and stimulus packages given to banks and large corporations. These subsidies were intended to trickle down to smaller businesses but that effect has been slow to occur. This recession was marked by an overall decline in small businesses (typically we see small business starts accelerate), decrease in mean employment size of small businesses, and a lack of turnover for the most tenured employees. All of this led to high unemployment rates. Optimism indexes show a similar trend: bigger businesses have gained in optimism at a faster pace than their smaller counterparts, contrary to past recoveries.

Contrast these trends with what has happened historically and it is clear that these anomalies are critical; any projection that relies too heavily on historical patterns is likely to be imprecise when the historical account materially differs from present events.

Moreover, the trends we’ve seen since the beginning of the recession are beginning to shift. Our data is finally showing that the smallest of businesses are growing more optimistic about their prospects, which will eventually lead to the increased hiring that typically comes at the start of a recovery. If the trend holds, it means that the typical post-recession jobs growth will be inverted during the current economic recovery. Thus, we should begin to see an acceleration in new jobs and rapidly decreasing unemployment.

Our firm has worked to tease out historical biases using proprietary data that was compiled in conjunction with Pepperdine University. Re-running the unemployment numbers using the same criteria as the Federal Reserve, our analysts project that hiring will accelerate at a rate sufficient to lower the U.S. unemployment rate to 5.0% by July 2015 in our most conservative scenario (data and methodology are available at www.DandB.com/unemployment_methodology).

We have been tracking the unemployment figures for a number of years, and have noticed a recent change in sentiment that has not been taken into account by other projections. For several years, Dun & Bradstreet Credibility Corp. and Pepperdine University have asked business owners of all sizes how many employees they plan to hire in the next six months in our quarterly nationwide survey of 3,000 businesses. Then, we compared that number to how many employees were actually hired. By calculating the difference between expectations and actions, we have been able to consistently use our survey to estimate future hiring based on business owner expectations. The results, when adjusted for business optimism, have been predictive within a small margin every quarter and consistently directionally correct.

The survey results were, unsurprisingly, negative during the recession and started to turn positive at the end of 2012, but only for the nation’s largest businesses. Medium-sized businesses followed suit and became more positive a few quarters thereafter. Again, this is in contrast to prior recoveries, where both optimism and hiring came first from our nation’s entrepreneurs.

Since the last quarter of 2013, our results have finally shifted positive for small businesses, both in optimism and in willingness to hire. This is the missing link in the standard unemployment predictions. Adjusting our survey numbers to normalize business optimism, we predict that more than 20 million jobs will be created by small and micro businesses in the United States in the next 18 months.

In addition to the hiring expectations of existing businesses, our methodology includes a forecast of job losses as well as jobs created by new businesses. The methodology does not account for significant changes in the civilian labor force, nor does it contemplate a continued decrease in the participation rate. While a decrease in the participation rate has the impact of reducing the unemployment rate, it has a long term detrimental effect on the overall economic infrastructure for the country. It is always better to drive unemployment lower by adding jobs than by removing workers.

The Federal Reserve projections are based on similar assumptions as our alternative model, and thus show a continued trend downwards, but the rate is likely understated as a result of not taking into account small business growth. If small businesses add jobs at the volume suggested by historical averages, the slope will accelerate more quickly. This can give us all confidence that we will see a steady drop to 5.0% unemployment next year.

May 28, 2014

Google’s Strategy vs. Glass’s Potential

When professor Tom Eisenmann first taught his newly released case on Google Glass at Harvard Business School, he asked his students which of three scenarios was most plausible: that Glass would catch on first in the enterprise setting, followed by gradual consumer acceptance; that adoption would be limited to early adopter “digerati” consumers; or that mainstream consumer adoption would happen rapidly.

Many students voted for the first scenario. They’re not alone.

Firms like Deloitte have predicted robust consumer demand for smart glasses, with global adoption reaching “tens of millions by 2016 and surpassing 100 million by 2020.” But early reports suggest that professions from medicine to manufacturing are interested while consumers remain wary. As Quartz reported last year:

Members of the Glass operations team have been on the road showing it off to companies and organizations, and they told Quartz that some of the most enthusiastic responses have come from manufacturers, teachers, medical companies, and hospitals. That suggests that they may be trying to persuade firms to buy the device and develop applications for it.

Sure enough, in April Google announced “Glass for Work,” an initiative aimed at developing more work-related apps on the Glass platform.

Glass may yet turn out to be a great consumer success. But in the meantime, Google’s choices in marketing and distributing its new product get to the heart of the tension between new opportunities and existing strategy.

Google’s strategy to date has been to build great consumer software, then extend these popular applications to enterprises with additional features, often at a fraction of the cost of competitors. Despite the Glass for Work announcement, it is clear both from the case and the company’s public positioning that it conceives of Glass first and foremost as a consumer device. In March, it announced a major partnership with Luxottica, the world’s largest eyewear company, a move clearly aimed at the mainstream market.

At the same time, the case indicates that the team behind Glass recognizes that it doesn’t yet fully know what it has created. Glass product manager Steve Lee is quoted as saying:

Major new consumer tech products are rarely brought out of the lab at this stage of development. But we knew that by putting prototypes into the wild, we’d start to learn how this radical new technology— something that sits on your face, so close to your senses—might be used.

One of the things they seem to have learned is that there is meaningful demand for enterprise applications.

Google has never been afraid to branch out beyond its core business; it expanded beyond search into email, chat, mobile operating systems, and more. But all these cases were complementary in that they were aimed at consumers.

Glass is different. It is one of the first products to launch out of Google X, the company’s research lab that aspires to “moonshot” innovations, and which is also developing a self-driving car. In 2013, BusinessWeek quoted Google X director Astro Teller as saying, “If there’s an enormous problem with the world, and we can convince ourselves that over some long but not unreasonable period of time we can make that problem go away, then we don’t need a business plan.” Of Glass, he said:

“We are proposing that there is value in a totally new product category and a totally new set of questions… Just like the Apple II proposed, Would you reasonably want a computer in your home if you weren’t an accountant or professional? That is the question Glass is asking, and I hope in the end that is how it will be judged.”

The comparison to the PC is telling. Google has been at the forefront of the trend toward consumer technologies being adopted by enterprises, but the history of computing contains more examples of the reverse. The adoption of computers by firms predated the rise of the PC, and the killer app for the Apple II was VisiCalc, the first ever spreadsheet program.

What if the opportunity in smart glasses really is in enterprises, or at the very least starts there? Should Google revise its strategy to pursue that opportunity?

Numerous frameworks exist for answering this question. Some emphasize the importance of sticking to innovations adjacent to a firm’s core business. Others suggest that a subset of innovation projects be aimed at entirely new markets, regardless of adjacency. Still others offer different deciding factors, like whether management is supportive. But ultimately Google is Google. With Google X the company is attempting to put its mark on the very process of technological innovation. In doing so, it will have to decide for itself whether innovation follows from strategy, or whether it’s sometimes ok for it to be the other way around.

Whatever the answer, there is a lesson here about transformative innovation. Though you may set out to explore strategic territory, there’s no guarantee that that’s where you’ll end up.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

How Boards Can Innovate

When to Pass on a Great Business Opportunity

How Samsung Gets Innovations to Market

Is It Better to Be Strategic or Opportunistic?

Zappos Killed the Job Posting – Should You?

Zappos is often out in front of new and unusual HR policies. It originated the “pay employees to quit” policy adopted by Amazon.com. And now, Zappos will abandon job postings, according to Stacy Donovan Zapar, Zappos’ Social Recruiting and Employer Branding Strategist. The “abandon job postings” policy recalls an earlier era — as Zapar says, “It’s old-school recruiting, made new and fresh again.”

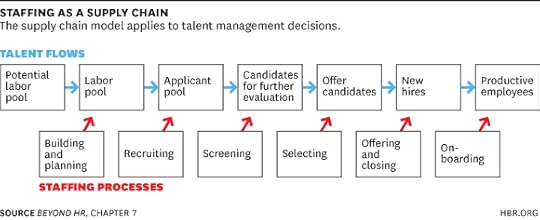

So does this mean you should abandon job postings too? The correct answer is “it depends.” Shiny new HR practices should motivate savvy conversations, not just imitation. In this case, organization leaders should demand a conversation about talent sourcing as sophisticated as one about their supply chain.

An important piece of context is that Zappos has long used social channels to describe their culture, people, and events. Now, they have added the Zappos Insider program, which Zapar describes as a place “where people can sign up, stay in touch, talk to real people with real names and real faces, get to know us and allow us to get to know them. Our Insiders are people who might like to work for Zappos someday … today, tomorrow or at some point in the future.” It’s an old-school idea common to technology companies as far back as the 1980’s, akin to “we know more about the engineers that work for our competitors than they do.”

Another context element is that this policy applies to call centers, which employ a large number of people doing jobs that are similar, easily described, and familiar to most applicants. These are pivotal roles with significant consequences at Zappos and Amazon.com. Indeed, Zapar notes that Zappos received over 31,000 applications last year, responded to every single person who applied, and hired only 300 of those applicants. So, Zappos had a large existing staffing investment to work with. The company still has job descriptions “with actual titles and actual job descriptions and actual requirements, we’re just not posting them externally anymore.” So, abandoning job postings doesn’t mean random hiring.

These policies can be effective for Zappos, but how should you decide if they are right for you? Approach that question logically, and with sound fundamentals. Let’s “retool” the Zappos strategy through the staffing supply chain, to see how their innovation can spur a great conversation.

Zappos has a “labor pool” with some applicants who “spam post” resumes. Their new policy can yield an “applicant pool” that weeds them out in favor of applicants who invest effort interacting with Zappos employees. Zappos hopes to “screen” and “select” better, as Zapar describes, “We’re having conversations with candidates, getting to know them — their strengths, their interests, their personality — and matching them to jobs on the back end. Hard skills match is 50% of the equation but, as Scott mentioned, culture fit is 50% of the equation for us.” Zappos might also see benefits at the “offering and closing” and “onboarding” stages, because decades of research suggests that candidates who devote effort to the recruitment process more readily accept an offer, and a “realistic job preview” increases candidate commitment and performance.

The staffing supply chain also reveals why the policy may not work for everyone.

Some applicants may be unwilling to spend time on the Insider site, particularly those with attractive alternatives. Zappos receives 100 applications for every vacancy, so they can probably take that chance. If your jobs are less familiar, more unique, or less attractive, your supply chain optimization may require getting more people into the pipeline, with an application process that makes it as easy as possible for them to apply, perhaps even an online job posting.

Zappos hopes the Insider site will help reveal culture fit, and believes that is best assessed through conversations and interaction. That sets a high bar for Zappos employees and hiring managers. They need to develop and analyze interactions rigorously and effectively. As Zapar said, “We’re just cutting those boring ole job postings out of the discussion and proactively chatting with candidates ahead of time so we know exactly who our top potential candidates might be by the time the opening becomes available.” Evidence suggests that chatting with candidates is not a valid approach, unless you invest in well-informed, disciplined, and skilled interviewers. At Zappos, the investment may be sensible, if 50 percent of performance hinges on culture and when the investment can be amortized across hundreds of yearly hires.

However, if you have a job for which the skills are rare, and can be identified from resumes or work samples, then your optimal supply chain should attract lots of resumes and work samples, perhaps even using algorithms rather than humans to winnow the pool in the early stages based on hard skills. You might even assess culture fit through deep conversations as Zappos does, but perhaps with a small number of well-trained interviews on a much smaller pre-selected group of candidates. You might “build” rather than “acquire” culture fit. Organizations like Disney, Toyota, and the military choose to use onboarding processes that nurture their unique cultural values beliefs and norms. If the talent you need is extremely rare, the optimal supply chain may not hire at all, but rather crowdsource from thousands of candidates who never become employees, removing the need to assess culture fit.

Companies like Zappos do a great service with their HR innovations, but that doesn’t mean you should simply copy them. HR and organization leaders should use them to pose good questions and have smart discussions.

When We Learn From Failure (and When We Don’t)

When do you pass the buck and when do you take the blame? New research shows most of us only cop to failures if they can’t be attributed to something – or someone – else. But when we dodge accountability, we prevent ourselves from learning.

In their recent HBS working paper, Christopher G. Myers, Bradley R. Staats, and Francesca Gino identify what they call an ambiguity of responsibility, which plays a powerful role in determining when you learn from failure and when you don’t.

It goes something like this: When we fail, we internally pinpoint what the authors call an “attribution of responsibility – namely taking personal ownership for the outcome or blaming it on external circumstances.” If you take personal ownership, their research shows you’re much more likely to learn from and work harder after that mistake.

But in cases when it’s unclear if you’re responsible for the failure, you’re “less likely to internally attribute a failure, and thus less likely to learn,” Myers told me. Importantly, he pointed out that this could be the case even when someone is highly accountable for the outcome. “Francesca Gino and Brad Staats have shown that surgeons learn far less from their own failures (learning instead from their own successes and others’ failures), presumably due to the ambiguity that comes from a bad surgical outcome – the surgeon is held accountable for the outcome, but it is unclear if it is his or her responsibility,” he said. “For example, there could have been an unforeseen complication, an error in another part of treatment, et cetera.”

Importantly, this means that even when people intend to learn from errors, the “ambiguity of responsibility” can undermine those good intentions.

The researchers came to these conclusions after putting volunteers through several experiments. In the one, subjects had to decide whether or not a car should be cleared for an upcoming race – a situation modeled directly after the Challenger explosion. One piece of crucial information – the likelihood of a gasket failure (99.99%) – was omitted, but available via a link. Later, the same group was given a similar test in which they had to identify a potential terrorist, with additional information available via email.

Those who had taken responsibility for their failure to prevent a car crash in the first example – “I just did not take the time to read all the information and jumped to a conclusion based on what was initially presented to me, without reading everything” – were more likely to be successful on the second task. Those who attributed their ultimately disastrous decision to an outside factor – “You can’t expect a person to make a responsible decision on any problem when you leave out one of the major key factors in it” – were less likely to succeed in identifying the fictional terrorist.

In a second round of experiments, subjects were told they’d failed on a blood-smear labeling task (even if they hadn’t), but given two different reasons: Half the group was informed they weren’t engaged enough in the task, while the other half received word there was a potential problem with the web browser they were using. The researchers found that the latter group often attributed their failure to the possible browser glitch. For example: “Apparently, the browser has some difficulty with displaying/labeling these images correctly and that could have hindered my overall performance.” When the entire group did the task again, those who’d been told that they weren’t engaged enough took more time (an indicator of increased effort) and performed better than the browser-glitch group.

The problem, in the real world, is that it can be incredibly difficult to decrease ambiguity when it comes to failure – after all, many of our assignments involve teams of colleagues, multiple stakeholders, glitchy technology, or other unpredictable factors. So how can managers encourage learning when it’s difficult to pinpoint responsibility?

Myers has a few suggestions, including removing the obstacles that can create ambiguity in the first place – a browser that may be faulty, for example, or complicated processes. “Managers could also think carefully about the role of job design – such as the scope of responsibilities and reporting structures – to craft jobs that don’t have ambiguity ‘blind spots’ built in,” he says.

It’s equally important to make failure safe within an organization. “Creating a culture of psychological safety, where individuals are encouraged to acknowledge and learn from failure, can help employees feel less psychological pressure to avoid internal attribution.”

He recommends trying non-punitive root-cause reviews when a team fails, which can result in both learning for those responsible and for other team members who can learn vicariously.

“This can certainly be a challenging cultural element to build,” he cautions. “But books like Failing Forward provide a number of great examples of these kinds of practices that might jumpstart a manager’s efforts.” Another place to start is in HBR’s 2011 failure issue, which includes an important article from HBS professor Amy C. Edmondson on how leaders can better understand failure and make it a central part of their strategies. Edmonson illuminates the big difference between knowing that failure is a valuable learning experience and actually making it a core part of a company’s ethos, and offers five key suggestions on how leaders can build a psychologically safe environment. Among them: create a shared understanding, or framing, around the types of failures that employees can expect to happen at work; and reward the messenger who brings up bad news.

“My experience is that we learn much more from failure than we do from success,” P&G’s A.G. Lafley told us in that issue. He’s right – but this new research, in addition to what we already know about failure, also demonstrates that learning depends on more than one person’s ability to suck it up and declare, as the white paper’s title puts it, “My bad!”

3 Priorities for Leaders Who Want to Go Beyond Command-and-Control

It’s cliché to say that “command and control” leadership is no longer relevant in most organizational contexts. But — especially in large, global, diverse organizations — what should it be replaced with? Leaders increasingly need to model traits that reflect the values and culture of the organization in which they operate. It’s nearly impossible to capture all those traits — every organization will have a different set of norms and customs. But there are at least a few essential leadership traits that we find common in many firms today.

First, in a world in which labor markets are fluid, leaders must inspire and impart purpose. When one of us interviewed young leaders for a book, two of the top three reasons they sought particular jobs were “intellectual challenge” and “opportunity to impact the world;” and other studies have consistently highlighted the increasing focus younger workers in particular place on purpose in the workplace. Anecdotally, that emphasis on finding purpose in our workplaces and in the companies we patronize — or as Simon Sinek might phrase it, starting with “why” — is redefining the way innovative companies like TOMS, Zappos, Whole Foods, and Google attract and retain talent. And at Red Hat, where one of us is CEO, the organization’s mission is a powerful catalyst in communities of customers, contributors, and partners for creating technology the open source way. The people who succeed in that context are those who are most inspired by that mission and are able to pass that inspiration to others and impart purpose in everything they do.

Second, as the pace of change in the marketplace quickens, leaders must adapt and engage. Many modern organizations simply can’t afford to hold constant for too long. To some extent that has always been true. One of our favorite quotes is from World War I German field marshal Helmuth von Moltke who said, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” The other favorite is Mike Tyson: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Command-and-control isn’t a fading leadership model simply for cultural reasons, but because modern organizations must respond in real time to fast-changing consumer preferences and agile competitors. This can only be done effectively when leaders have engaged their organizations deeply enough that employees aren’t simply executing tasks; they’ve understood and internalized the “whats” and “whys” of the strategy deeply enough that they can innovate on and improve that strategy as the market demands. This requires intensive, one-on-one work. At Red Hat, for example, the senior team is held accountable for how associates (Red Hat’s way of referring to “employees”) answer the question: “I understand Red Hat’s strategy and what I can do to make it successful.” This call for engagement and adaptability also requires leaders who are willing to empower the community to adapt and solve problems, and who are willing to listen to those with whom they work rather than simply doling out commands.

Finally, in this environment so reliant on inspiration, purpose, and engagement, leaders must embody authenticity. Bill George, among others, has written eloquently on the demands of authenticity for some time; but the demands of authenticity — and the ways in which colleagues can perceive a lack of authenticity — are widening. In our travels speaking to young and senior leaders alike about the changes technology is catalyzing in modern organizations, the theme of increasingly blurred personal and professional lives — wrought by a combination of social media and “always on” mobile technology — has been perhaps the most prevalent. Coworkers know who you are and what you value and can more easily discover when your personal values and actions conflict with what you say in the workplace. We see this as positive because it allows leaders to be themselves at work — vulnerabilities, values, and all — and view those very vulnerabilities and emotions as a central way in which leaders can connect with coworkers in deeper, more human ways, an opinion shared by others like Brene Brown. This very personal approach to authenticity also helps reinforce the truth that there is no one prototypical effective leader. A variety of leadership traits and characteristics may succeed in different circumstances and their combination in the context of a team leads to strength in diversity.

Are you and the leaders with whom you work learning to adapt to a changing model of leadership? Certainly, there are a multitude of traits that will be important depending on the context in which you work. But inspiration and purpose, adaptability and engagement, and authenticity will be critical to most leaders in the information economy.

Managing a Negative, Out-of-Touch Boss

The most frequent question I get asked by the 250,000 people enrolled in my MOOC on leadership is, “How do I deal with my boss who is not only dissonant, but quite negative?” These bosses are “dissonant” in the sense that they’ve lost touch with themselves, others and their surroundings — and it’s nothing new. They come across as negative, self-centered, focused on numbers, and their employees feel like they’re being treated as resources or assets (not as human beings).

Why are these people still in management positions? Often, it’s because we excuse them for their incompetence or rude behavior because they are a rain maker – maybe they brought in the largest client the company has ever had, or maybe one of their parents owns the largest share of stock. Sometimes, we excuse them based on organizational norms (i.e., people can be excessively analytic), or policies that make it so difficult to fire someone that we live with such incompetence. You’d think that with all of the MBA programs and management education that exists today, we would have changed this dynamic by now. But sadly, empirical evidence suggests just the opposite — these programs often focus on analytics, and — as I explain below — chase out the ability to be open to new ideas.

Even an effective leader or manager can become dissonant (i.e. lose touch with others, clients, the environment) over time. Usually, it’s because they’re too analytic. They focus on metrics, numbers, and analyzing problems. In doing so, they overemphasize a neural circuit called the “Task Positive Network (TPN),” which is useful for focusing, solving problems and making decisions. We know from neuroscience that , which is key to being open to new ideas, people, and moral issues. People with a suppressed DMN have trouble seeing others around them. Sometimes a boss is dissonant because he or she is a negative person, or egocentric, or just plain scared and defensive. None of this excuses their inappropriate behavior. But it does help us understand why they are suffering from a syndrome in which chronic stress or defensiveness has eroded their ability to renew themselves and be courteous, pleasant, and often much more effective.

So what do you do if you have a boss who’s fallen into this trap? First, recognize that these bosses are diminishing themselves and their ability to effectively lead others. They can deliver on known tasks — mostly routine tasks — but this style returns the least amount of innovation, the lowest levels of employee engagement, and often the lowest performance from teams.

Second, it’s key to talk to a boss like this. See if a frank conversation can help him or her move into what my colleagues and I called the Renewal Process. Ask him or her to envision a desired future over coffee, lunch, or dinner with questions like: “What could this organization be like in 10-15 years if everything were ideal?” You can do this by asking about the core purpose of the organization, or even its noble vision. “What is our purpose?” Not, “how are we doing?” but “why do we exist and how do we serve our organization and society?” Sometimes, you can get to the same place by asking about core values and virtues: “If we were being consistent with our values, how should we act with each other? with our customers/clients? our vendors? our community?”

From the point of view of neuroscience, all of this will arouse the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) by activating the DMN, which is the state in which your body can rebuild itself and the only way to recover from stress. I know what you’re thinking: “I shouldn’t have to be my manager’s therapist.” True. But, you can be a valued friend or advisor, even to your boss.

Remember that your boss didn’t become a carrier of negativity overnight. Reversing it will take even longer. But, brief chats about positive topics might, to paraphrase from Star Wars, “Bring them to the light side of the force.” It is my experience that this approach will work 20-30% of the time. And when it does, you will have rebuilt a positive relationship with your boss and helped him or her become an effective leader once again.

If that doesn’t work, try the third option: You may be able to get your boss some help. Find out if your boss has a coach or a trusted advisor. Who does your boss talk to when he or she wants advice or help? Talk to a thoughtful senior person in HR about coaching for your boss.

If nothing seems to be helping, then your fourth option is to protect yourself and your sanity. Upgrade and increase the frequency of positive renewal activities in your personal life and work day (i.e., meditation, yoga, exercise, prayer, helping others, playfulness, feeling hopeful about the future). Your job is to protect yourself, your people and your organizational unit. But, this can be exhausting and overwhelming. And while you might not see the consequences at work at first, your family may begin to feel them. And work could become just that — work — and not the fun and exciting challenge it used to be.

This leads to the final option — leaving! There comes a point where you need to protect your own creativity and spirit and find something else to do or somewhere else to do it. Because life is too short to waste it dealing with an out of touch boss.

Focus On: Conflict

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Conflict Strategies for Nice People

Senior Managers Won’t Always Get Along

When Your Boss Is Too Nice

Think Twice Before Eating Pretzels Directly Off Your Tray Table

In an experiment, E. coli bacteria survived and was highly transmittable for 72 hours after being dabbed on airline tray-table surfaces, according Kiril Vaglenov and James Barbaree of Auburn University. Their study, conducted on behalf of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, also found that the bacteria survived for 96 hours on armrests. The researchers obtained the tray-table and armrest material from a major airline, inoculated it with the bacteria and exposed it to typical airplane conditions.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers