Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1417

June 2, 2014

When to Resign, and When to Clean Up the Mess

The resignation of Eric Shinseki, the now-former U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs, doesn’t solve the problem of an appallingly inefficient VA hospital system with long waiting times for treatment and deaths that happened while veterans waited for care. When should a leader resign, and when should he stay and clean up his mess? Should Shinseki (and President Obama) have resisted calls for his ouster, so that he could stay to address the problems?

We measure a leader, not by the absence of problems, but how he or she confronts those problems and takes action.

Jamie Dimon is still CEO of JP Morgan Chase, despite financial controversies and big legal settlements of the kind that toppled CEOs of other banks; he has guided the cleanup process, apparently effectively. PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi is leading a course correction (no scandal involved) after some analysts said she had taken her eye off the core product and thus should tender her resignation. John Chambers has led Cisco successfully for nearly 20 years through numerous ups and downs including dismantling a messy, controversial organizational structure of his own making (a complicated overlay of councils and boards). Boeing CEO Jim McNerny tackled the life-threatening battery problem on the new 787 Dreamliner aircraft, going from crisis to triumph. Elon Musk of Tesla is one of numerous entrepreneurs who prove their critics wrong by rising to the occasion when fires break out, eventually winning back public trust. And on college campuses right now, after rape and sexual abuse scandals have burst into public knowledge, presidents are still in place changing policies and practices.

Generations of Western middle class parents taught their children to clean up their own messes. In adult institutions, that isn’t always possible or desirable. For every Chambers, McNerny, and Nooyi who handles clean-up, there’s a Shinseki that must resign. Here’s what boards and bosses should ask leaders, and leaders should ask themselves, about when to resign, or when to stay for the clean-up campaign.

How mission-critical is the mess? Is the scandal isolated, or evidence of a widespread systemic problem that hasn’t been addressed? Isolated incidents can be dismissed as unfortunate tragedies. But when a problem pops up in more than one place, and it is central to the mission, and the leader doesn’t already have a plan in place for fixing it, then it is time for the leader to go. That applies clearly to the VA, where the delays in treatment are core, and Shinseki was in place long enough to have figured this out.

What did you know, and when did you know it? Did you take immediate action? Leaders should be the first to know, not the last, and when they know, they should take corrective action fast. When then-Johnson & Johnson CEO Jim Burke learned of a Tylenol tampering incident, he immediately ordered the removal of all Tylenol bottles from the market, and sorted out cause and responsibility later — a famous lesson since taught to generations of business school students. Soon after becoming CEO of General Motors, Mary Barra faced revelations about extensive automotive defects and deaths attributed to them. She immediately made some executive changes, such as appointing a safety officer, and created action plans. She faced a tough situation for a new CEO, especially one who had previously headed the global product development organization, but her swift actions have given her credibility for longer-term changes.

Are you a distraction? Have you become the story? New brooms sweep clean. But leaders who linger after messes surface can get stuck on a failed approach, and they can appear more interested in keeping their jobs than helping the organization achieve its mission. Tony Hayward had to step down as BP CEO after the explosion and oil spill in the U.S. Gulf because of how he handled it; he made headlines by whining about what was happening to him, rather than focusing on the human lives lost and economic costs for the region.

Just as cover-ups are usually worse than crimes, it’s not having a mess on their hands that causes leaders to fail; it’s how the mess is handled — the timing, communication, accountability, and compassion. Get those right, and you can continue to handle the clean-up. Get them wrong, and it’s time to get out of the way.

Shinseki, a highly-decorated military veteran, did the honorable thing. He also did the inevitable thing. Cleaning up a mess requires strong will, fast action, new approaches, and a lot of credibility. One resignation doesn’t restore trust, but it opens the door for someone who can.

How Xiaomi Beats Apple at Product Launches

The iPhone 6 is due in September.

The build-up to its launch will almost certainly follow the Steve Jobs M.O. Device specifications will remain a closely guarded secret until the launch date (unless an employee forgets his phone at a bar). There will be long lines at stores. We probably won’t be able to actually get the product for a couple of months after the launch. And, of course, users (we) will have no input into what we actually get; Steve Jobs’ dictum that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them” is still an act of faith for Apple’s management.

But is this the only way to launch new products? Let’s think for a second about the risks inherent in this approach. Imagine that something goes wrong and a hardware glitch makes it necessary to recall and/or repair all products (remember the iPhone4 Antenna problem)? Or what if a certain feature or the device as a whole is a complete miss with consumers (think Apple Maps)?

All this secrecy comes at a price, both in the supply chain and by creating a difficult workplace. Consider how many people have to keep the secrets: factory workers, supply chain workers, and retail employees. Current employees will work weeks of overtime and self-employed contractors will be hired in the thousands. According to some media outlets, Apple already announced restrictions for employee vacation in Germany, probably because of the launch. This elaborate planning process is complex, expensive, and risky.

But what is the alternative? In “Why The Lean Startup Changes Everything,” Steve Blank argues for “experimentation over elaborate planning, customer feedback over intuition, and iterative design over traditional ‘big design up front’ development”. Blank’s approach is as relevant to new product launches as to new companies: they are also highly uncertain, with many unknown unknowns.

One of Apple’s competitors is already applying just such an approach to new product launches. Founded in 2010, Xiaomi is one of the biggest Chinese smartphone companies. Its revenues last year were already more than $5 billion — not bad for a three-year old.

Unlike Apple, Xiaomi produces its products in small batches, allowing for easy changes based on user feedback. Every Friday there is a major feature update of the operating system and a round of feedback from expert consumers. Because Xiaomi only sells directly to consumers (unlike Apple, which goes through many intermediaries), the company can collect all this feedback and build it into the next generation of devices.

In essence, the phone you buy this week can be different from what you’ll buy next week. As one example of the benefits of this approach, Xiaomi got its operating system translated into 24 languages by users and the company didn’t spend a dime. User feedback led to the creation of a very different and much more flexible device. Xiaomi allows users to swap the battery, replace a memory card, change case backs, and remove the SIM card.

Don’t get us wrong: we are not saying that Xiaomi has a better product than Apple: they are priced differently and they appeal to different segments of the market. We both use iPhones, not Xiaomi products. But many companies that try to take clues from Apple’s playbook on innovation will fail because they don’t have the marketing clout and brand appeal to push products rather than pull ideas. Further, Apple’s model is driven by the creative genius of individuals like Steve Jobs, who are not easy to find. Without these resources, a company might be much better off following the Xiaomi playbook.

If You Have a Lot of Work to Do, Hope for Rain

Bad weather is better than good weather at sustaining people’s attention and maintaining productivity, according to a study by Jooa Julia Lee of Harvard University, Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School, and Bradley R. Staats of the University of North Carolina. In a study of Japanese bank workers whose windows gave them a view of the weather, a 1-inch increase in daily rainfall was related to a 1.3% decrease in worker completion time for data-entry tasks. When the weather is bad, workers are less distracted by thoughts of outdoor activities.

The True Cost of Hiring Yet Another Manager

You can have terrific people working in the right teams and still not see the financial results you’re hoping for. Why? It could be that your organization’s structure is creating obstacles that compromise your workforce’s performance.

One common culprit is out-of-control tooth-to-tail ratios. In a war zone, some soldiers fight on the front lines. Others maintain supply chains, handle logistics, and otherwise support those front-line troops. Military commanders know they can’t let the tooth-to-tail (or combat-to-support) ratio get too low, or they’ll wind up with a force that costs too much and can’t win the battle.

It’s the same in a company. You have front-line employees who create what you sell or who deal directly with customers: software developers, sales reps, call-center staffers, and so on. You also have support staff, including the people in marketing, finance, HR, and other functions. When the tooth-to-tail ratio gets too low, front-line people find that they have to send every customer request or idea for improvement up through the bureaucracy and wait days or weeks for a response. That not only creates long delays for customers; it also makes front-line employees feel disempowered and demoralized. How can they serve the customer when they’re burdened with so much bureaucracy?

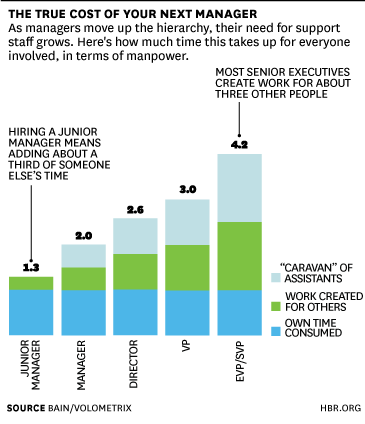

A second likely culprit: too many supervisory layers. Unnecessary supervisors create work and don’t increase efficiency, thus lowering an organization’s productivity. And companies often underestimate how expensive all those supervisors really are. Not long ago my colleagues and I studied the cost of adding a manager or executive, and we found a kind of multiplier effect (see the graphic below). When you hire a manager, he or she typically generates enough work to keep somebody else busy as well. Senior executives — SVPs and EVPs — are even more costly. These high-priced folks typically require support from a caravan of assistants and/or chiefs of staff. The support staff generates a lot more work for other people, too. The extra burden comes to 4.2 FTEs per hire, including the executive’s own time.

We’ve found three steps to be helpful in liberating your people from the organizational mire:

Manage your tooth-to-tail ratios closely. Appropriate ratios naturally vary from one industry to another. But a company can gauge its performance against benchmark levels and make adjustments as necessary. If you can create standard processes for handling queries and ideas from front-line people, that will help them make and execute good decisions faster. You may find that all those support personnel aren’t really necessary — that the tooth can be more effective with a much smaller tail.

Trim your supervisory layers. Compare your managerial spans — the average number of direct reports per supervisor—with industry benchmarks, and adjust your structure accordingly. Take into account, however, that different jobs require different spans of control. The lawyers in your legal department probably do highly specialized work that needs close supervision, thus requiring a narrower span of control. The custodians who clean your facilities, by contrast, can operate under a supervisor with a much broader span of control. Selectively removing supervisors (sometimes referred to as “delayering”) can reduce workload and costs throughout your organization.

Limit the caravans. It does little good to eliminate unnecessary supervisors if those who remain are as costly and inefficient as ever. In some companies, it’s common for senior VPs to have not just an assistant but a whole coterie of helpers, complete with a chief of staff. These caravans can generate just as much work as the executives themselves — again, a perverse multiplier effect. Limiting (or eliminating) these caravans reduces work and cost.

Some companies have begun to attack these organizational barriers. A large software company we worked with recently eliminated more than 40% of its supervisors, ensuring that the people who actually develop the product aren’t overburdened with managers and other functionaries. When Alan Mulally first became CEO of Ford, he did away with the CEO’s chief of staff position. It was a double-barreled message on Mulally’s part: not only wouldn’t he have a chief of staff; he wouldn’t have a staff at all. His decision precipitated similar moves elsewhere in the organization; no EVP wanted to have a chief of staff when the CEO didn’t.

Chances are that your top performers want to live up to their full potential. Don’t let organizational obstacles get in their way.

May 30, 2014

Even Small Negotiations Require Preparation and Creativity

Whether you’re aware of it or not, you’re negotiating all the time. When you ask your boss for more resources, agree with a vendor on a price, deliver a performance evaluation, convince a business partner to join forces with your company, or even when you decide with your spouse where to go on your next vacation, you’re taking a potentially conflict-filled conversation and working toward a joint solution.

That’s what a negotiation is — a process in which two parties with potentially competing incentives and goals come together to try to create a solution that satisfies everyone.

Too many people think that negotiation is something that salespeople or procurement professionals do, but it’s something we all do — every day. And it’s not just high-stakes, months-long discussions that warrant a thoughtful approach. It pays to improve your ability to handle all of these situations. This means honing skills such as conflict management (as you’d expect) and creative thinking (which you might not), both of which are critical to reaching mutually beneficial decisions.

I’ve heard many people say that being a good negotiator is about thinking quickly on your feet or being a better orator or debater than your counterpart. Sure, those things are helpful. But the best negotiators I’ve seen in action—the ones who most often get what they want — are those who are the most prepared and the most creative.

First, preparation. Preparation is the key to any successful negotiation, but few people spend enough time on it. I’ve had sales leaders tell me that they prepare in accordance with how long it takes to get to their customer’s office. That’s fine if your meeting is in Tokyo and you live in Manhattan. But it’s a recipe for disaster if you’re meeting the customer in Brooklyn.

Instead of using travel time as a benchmark, you should put at least as much time into getting as ready as you think the negotiation will take — at a minimum.

This is true for even seemingly straightforward discussions. If you’ve scheduled a two-hour conversation, spend at least two hours getting ready. And the more complex the issues at hand, the more you need to prepare — at least double or triple the length of time you’ll spend at the table.

There are times, of course, when you won’t be able to thoroughly prepare: You see your boss on your way into a meeting, for example, and you have to agree on when you’re going to get him that report; a vendor shows up unexpectedly and wants to negotiate a new volume purchase; or a customer calls demanding a price concession. Under those circumstances — and in advance of any negotiation — it’s helpful to start asking yourself what your key interests are and what the other party’s might be, thinking of creative solutions, and identifying persuasive standards. If you think of the discussion as a negotiation rather than a quick check-in, you’re more likely to treat it with the discipline it deserves.

Second, being creative — when preparing and in the room. The goal in any difficult conversation is to end up with the best solution out of many possible options. The more options you have at your ready, the more creative you can be. When brainstorming options in advance or face-to-face with your counterpart, your goal is to develop possible solutions that meet the interests of everyone involved in the negotiation — those deeper needs behind your positions.

Before you negotiate, write down as many good, bad, and crazy ideas as you can think of; don’t settle for one or two options. Aim for at least seven or eight, even in a simple negotiation, and many more in a complex one. Allow yourself to come up with solutions that seem unrealistic — often from those impossible options, you’ll see a path toward a more viable one. Each solution you come up with may not address every need you and your counterpart have, but each should address at least a subset for both parties.

When doing this in advance, don’t worry about whether you’ll divulge these options to the other party when you get into the room; just be creative. If you run out of steam, go back and consider your interests and theirs, and see if you can come up with new options that address complementary sets of interests or bridge conflicting ones.

Treating every potentially conflict-filled conversation like a negotiation that you need to prepare well advance for and be creative about will help you will help you achieve the results you want whether at home with your spouse or at work with your colleagues, customers, or suppliers.

This post is adapted from the forthcoming HBR Guide to Negotiating .

Focus On: Negotiating

Make Your Emotions Work for You in Negotiations

The One-Minute Trick to Negotiating Like a Boss

How to Negotiate Your Next Salary

Should You Eat While You Negotiate?

Is Management Due for a Renaissance?

Every now and then, a thinker calls for a renaissance in some field of work – a rebirth, or return to classic roots after a period of straying from them. Is management – not yet a very old discipline – due for one? When Richard Straub, President of the Peter Drucker Society of Europe, recently declared so, it got me thinking by analogy about how one might come to pass.

The first Renaissance was of course the sweeping cultural movement that began in 14th century Florence and, aided by the newly invented printing press, spread throughout Europe. It lasted into the 17th Century, when it was succeeded by the European Enlightenment. The causes of the movement are complex and much debated. During the long decline of the Roman Empire, Italy experienced a steady influx of Greek scholars and texts. Their appearance sparked a new interest in classical writings. At the same time there was growing criticism of the sterile scholasticism of the medieval universities, which had focused on defending dogma with rigorous conceptual analysis and vigorous argument. Instead, there was a new focus on nature and experience and what it meant to be human. Some say that the Black Death, which hit Italy particularly badly in the mid-14th century, catalyzed this concern with humanism. Instead of being preoccupied with the afterlife, people turned their attention to life on earth. Thus the recovery of ancient wisdom was accompanied by the pursuit of new perspectives (quite literally, in the case of painting) that would render a more realistic picture of the human condition.

We could even say that the subject of management was touched by that first Renaissance. Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) was one of the first writers to give us an unvarnished perspective of how things really are in powerful enterprises, rather than how we would like them to be.

What would a second Renaissance look like in management today? The field as we know it was born as a set of practices for organizing work that took hold in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was radically reformed in the 1950s along what were then conceived to be scientific lines. Although this reform had valuable benefits at the time, someone calling for a second Renaissance might argue that in the decades since then it has degenerated into a new scholasticism, dominated by the sterile dogmas of neoclassical economics. In particular, the economic focus on the individual and instrumental rationality has led to a preoccupation with methods and means, almost to the exclusion of aims and ends. Coupled with mechanical models, this has resulted in an engineering management mindset, in which people are inevitably seen as instruments for another’s purpose, rather than as ends in themselves. The effect of this has been the widespread disengagement of people from work, and the apparent inability of large, successful organizations to innovate.

A second Renaissance would call for a new approach to learning – a humanistic return to experience, practice, and the cultivation of judgment and practical wisdom in managers. Just as was the case with its predecessor, this renaissance would involve a blend of ancient wisdom and new perspectives.

The “scientific model” of management, as Warren Bennis and Jim O’Toole called it (in their 2005 HBR article “How The Business Schools Lost Their Way”), emphasized conceptual knowledge and tools and techniques – what Greek philosophers would have called episteme and techne. It was assumed that organizations could be studied by detached “objective” observers and that management science could be “values-free” – just like the natural sciences. More generally this scientific model has resulted in a misanthropic concept of capitalism that excludes purpose and meaning from its concerns.

A second Renaissance would call for a recovery of the concept of practical wisdom; of what Aristotle called phronesis. Phronesis is prudence, the context-dependent, practical common sense needed when we have to make judgments about what is right and wrong – “what is good or bad for man”, as Aristotle put it. From this perspective a “phronetic” discipline like management can never be “values-free”; all management decisions have ethical implications because they deal with people. And people can be passionate participants as well as (occasionally) detached observers; it’s “both…and”, not “either/or”.

We have learned a lot about the nature of humankind since the 1950s. In his best-selling book The Righteous Mind, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt likens the human mind to a rider (reason) on an elephant (intuition). Back in the 1950s we thought that the rider was in charge, or ought to be. Evidence is accumulating from several fields that this view is wrong; the elephant is in charge and the rider is a much better rationalizer in hindsight than a reasoner in prospect. It seems that, with our limited conscious mental capacity, our minds have evolved to make fast “good enough” decisions under pressure of time and conditions of uncertainty. Sometimes, especially in evolutionarily unfamiliar contexts, these intuitions play us false, but most of the time they work just fine and we couldn’t live without them.

The challenge is not to replace intuition with reason as the management reformers of the 1950s had hoped, but to develop new understandings of how intuition and reason can work together, especially in the service of creativity and innovation. Once again, it’s “both…and”, not “either/or”.

Believers in the scientific model of management have resisted this view by adopting a “glass half-empty” attitude toward our cognitive powers under the pejorative heading of “heuristics and biases”. As a result, the new findings from the cognitive sciences have not changed our concept of human nature but are being used as springboards for further manipulations. A humanistic second Renaissance would resist this purely instrumental approach by calling for a “glass half-full” attitude toward our mental abilities. It would harness the liberal arts to study the new evidence for its implications for human nature and creativity and what it tells us about how people grow and become engaged with the world. It would recognize that we are social creatures with minds that are embodied, not just “embrained,” and that we can “think” about the world in just as many ways as we can experience it. Our resulting capacity for analogical thought is the key to creativity.

Like the first Renaissance, the great transformation people are increasingly calling for in management must be fundamentally philosophical. It won’t follow from the adoption of new principles and precepts, rules and tools, although these will surely be invented. Rather it begins with a new synthesis, a new integration of knowledge that already exists but currently lies scattered and incoherent.

This post is part of a series of perspectives by leading thinkers participating in the Sixth Annual Global Drucker Forum, November 13-14 in Vienna. For more information, see the conference homepage.

It’s Time to Re-Imagine Mary Meeker’s Internet Trends Report

Any journalist who has spent time in or near the tech industry knows about, and looks forward to Mary Meeker’s annual Internet Trends Report. It houses a ridiculous volume of data about where the tech industry (and thus, the economy) is pointed. The clumsy slides overflowing with bullet points, photo clips, and ’90s-era charts and graphs never feel amateurish so much as entrepreneurial, the product of the passion and audacity of trying to capture a thorough picture of such a dynamic industry. There is so much to say — who has time to refine the actual presentation?

The 2014 Internet Trends Report continued the tradition and was inevitably hailed as a must-read. Meeker uses the “re-imagining” theme as she has in the past, this year focusing on re-imagining messaging, apps, content distribution, money, a vertical industry, and even day-to-day activities.

But as I clicked through its 164 pages, I found myself thinking that what actually needs re-imagining is the Internet Trends report itself.

I had already read about most of the trends Meeker had identified. Some of her points felt not just familiar, but outdated. Yelp, Airbnb and Uber as examples of “re-imagining user interfaces” (pages 77-79) felt like old, old news, and missing crucial recent context. The section on the proliferation of screens is an established enough trend that Quartz has launched an entire site devoted to the idea.

None of this is to blame Meeker. It’s an annual report. For identifying tech trends, that approach is impossibly antiquated. A year ago, Twitter was nearly six months away from going public. And in the six months since its IPO, Twitter’s been through a honeymoon, a backlash, and a backlash to the backlash.

The data used in the report to identify trends is data we get in near-real-time now, streaming through our social feeds and inboxes, and pulled in through search. This data is a commodity now. What we need is more analysis and debate over what it means.

But the trends report doesn’t ever get to the analysis and debate. That’s what’s most frustrating. It stops short of examining the deeper, more complex questions surrounding trends it can no longer claim to spot.

For example, Bitcoin is shown to be a growing trend (“re-imagining money”), but we’re way past establishing that, aren’t we? We’ve moved on to the headier questions: Is it currency or property? Can it be trusted? There’s a hopeful section on the rise of tech in education, but it’s just some stats on the number of users, with no analysis of how apps can and will improve education. Impressive growth in Internet TV is charted; nothing about the crucial battles between disruptors like Aereo and Roku and the established cable and content providers. Netflix is hailed as an analytics champion, but there’s no mention of the most important trend of all with regard to Netflix, and possibly to the entire Internet—the ongoing tinkering with net neutrality.

This reflects the nature of the tech industry itself, which is optimistic to a fault. (If you’ve been watching Silicon Valley on HBO, you’ve seen this trope hilariously lampooned). It also reflects the fact that Meeker’s report was intended to quantify all the trends that matter, not to explain or question them.

But what if that purpose changed? In the spirit of “re-imagining” that dominates the report, let’s re-imagine what the Internet Trends report could be going forward to make it fresh, must-read material.

First, it should be published more frequently—weekly? monthly?—and it should be unbundled and distributed socially. No one report would attempt to encompass the entirety of internet trend. A variety of reports would instead look exclusively at specific trends, still based on data, but with more emphasis on the analysis. Example: A chart on page 38 shows a surprising uptick in Pinterest’s unique visitors in the past six months. It’s now second only to Instagram in the image/video sharing category while Tumblr is, well, tumbling. What’s that about? A monthly report could take on this smaller slice of the greater trend with focused data and analysis in a way the annual report doesn’t and can’t.

More frequent reporting would allow Internet Trends to become more narrative and less declarative. As it stands with its breadth and lead time, each report feels too isolated. For example, in 2012, some of the “re-imaginations” were note-taking, drawing, photography, and home improvement. One never feels like these are trends - ongoing patterns we’re going to follow up on and watch evolve. Even the trends that appear in successive years (in 2012 an Uber-driven “re-imagination of calling a cab” appeared) feel unconnected to data presented in ensuing years.

Moving to a more frequent publishing cycle would allow the trends to become living things that evolve over time, along with their data and the analysis around them. Imagine trying to understand a company’s performance from annual reports alone versus tracking it through more frequent data and quarterly performance calls.

Finally, a new Internet Trends should be more beautiful. I’ve always forgiven the report’s charts, but my attitude toward them changed this year. The assault of colors (page 96), number labels (page 21), double-y axes (page 104), and insider acronyms is overwhelming. The visuals don’t seem worse than in previous years (though there are a couple of egregious errors: the charts on declining computing costs [pages 70-72] are just scaled incorrectly). Data visualization has sped past this level of execution. It’s not hard to make better charts than this anymore. Persuading with data is serious business, and as the tools and practice of the craft have improved across the web, our tolerance for poor craftsmanship has gone down. Good visual presentation increases our likelihood to use that mobile, social web that Meeker rightly cites as so powerful.

What I’m describing is hardly provocative. It’s a more focused version of what Nate Silver is trying to do with 538 and what Ezra Klein is trying to do with Vox, and what in fact most content sites are beginning to do as the content-based Web enters its next phase. But I’m not hopeful that Internet Trends will evolve. It’s possible, even likely, that Meeker has no incentive to turn into the next internet thought celebrity.

And that’s too bad. What was once an eagerly awaited moment feels like it matters less and less. Internet Trends has been disrupted, a victim of the very trends it has tried to capture for two decades.

The Best Teams Hold Themselves Accountable

Want to create a high performance team? Want to limit the amount of time you spend settling squabbles between team members? It turns out those two issues are closely related: Our research shows that on top performing teams peers immediately and respectfully confront one another when problems arise. Not only does this drive greater innovation, trust, and productivity, but also it frees the boss from being the playground monitor.

I first saw the connection between high performance and peer accountability years ago when consulting with a very successful financial services company. It had an unparalleled return on capital, breathtaking sales growth, and the highest customer renewal rate in the industry.

In my first face-to-face meeting with the CEO, whose name was Paul, and his direct reports, I committed a major faux pas. I discovered halfway through the meeting that I was calling the wrong guy, “Paul.”

It was an innocent mistake. When it was time to begin, one member of the executive team wasn’t present. He showed up six minutes late and the guy at the head of the table (I learned later that his name was Frank) said, “We all agreed to be here at 10 AM—what happened?” It was a jarring moment. The tardy teammate flushed red, stammered an explanation, and the meeting moved on. I assumed since this guy was at the head of the table and he held the latecomer accountable that this was Paul. I smiled and made a small wave at him. He looked confused but waved back.

Ten minutes later, Lydia was reporting on sales in her business unit. Apparently, things weren’t going well. The woman next to me asked most of the hard questions about her disappointing performance. Her comments were thoughtful and constructive but firm. She concluded by suggesting that they reconsider how much capital they were deploying in Lydia’s business unit that year. I wondered if maybe she was in charge.

The best decision I made that day was to keep my mouth shut. It turned out Paul was the quietest guy in the room. I could have spent the entire time playing “Who’s Paul?” and gotten it wrong every time. (This has since become one of my favorite stories illustrating the importance of peer accountability.)

There was something strange about that team. And many other teams we subsequently studied. We’ve found that teams break down in performance roughly as follows:

In the weakest teams, there is no accountability

In mediocre teams, bosses are the source of accountability

In high performance teams, peers manage the vast majority of performance problems with one another

Paul didn’t have to monitor latecomers or ask Lydia hard questions because he had created a culture of universal accountability. The basic principle was that anyone should be able to hold anyone accountable if it was in the best interest of the team. Team members were both motivated and able to handle the day-to-day concerns they had with one another, with him, or with anyone outside the team.

We’ve found that you can approximate the health of a relationship, a team and an organization by measuring the average lag time between identifying and discussing problems. The shorter the lag time, the faster problems get solved and the more the resolution enhances relationships. The longer the lag, the more room there is for mistrust, dysfunction, and more tangible costs to mount. The role of leader is to shrink this gap. And the best way to do it is by developing a culture of universal accountability. Here are some ways we’ve seen managers like Paul create this kind of norm:

Set expectations. Let new team members know up front that you want and expect them to hold you and others accountable.

Tell stories. Call out positive examples of team members addressing accountability concerns. Especially when they take a big risk by holding you accountable. Vicarious learning is a powerful form of influence, and storytelling is the best way to make it happen.

Model it. The first time your team hears you gripe about your own peers to others—rather than confronting your concerns directly—you lose moral authority to expect the same from them.

Teach it. The best leaders are teachers. Codify the skills you think are important for holding “crucial conversations”—and take 5-10 minutes in a staff meeting to teach one. In these teaching episodes, ensure the team practices on a real-life example— perhaps one that happened recently. Trust me, they’ll complain, but this will make a huge difference in retention and transference to real life.

Set an “It takes two to escalate” policy. If you struggle with lots of escalations, set a policy that “it takes two to escalate.” In other words, both peers need to agree they can’t resolve it at their level before they bring it to you together.

The role of the boss should not be to settle problems or constantly monitor your team, it should be to create a team culture where peers address concerns immediately, directly and respectfully with each other. Yes, this takes time up front. But the return on investment happens fast as you regain lost time and see problems solved both better and faster.

Focus On: Conflict

Managing a Negative, Out-of-Touch Boss

Most Work Conflicts Aren’t Due to Personality

Conflict Strategies for Nice People

Senior Managers Won’t Always Get Along

You Can’t Delegate Change Management

Many managers, even at the most senior levels, don’t fully appreciate the difference between announcing a major change initiative and actually making it happen. When senior leaders disappear after a big change announcement, and leave lower-level managers to execute it, they are missing in action. And it’s probably more common than most realize.

The announcement is the easy part; it makes the manager look bold and decisive. Implementation is more difficult, because no matter how good and compelling the data, there will always be active and passive resistance, rationalizations, debates, and distractions – particularly when the changes require new ways of working or painful cuts. To get through this, managers have to get their hands dirty, engage their teams to make choices, and sometimes confront recalcitrant colleagues – none of which can be delegated to subordinates or consultants.

Consider this example.

The CEO of a large telecommunications firm announced an enterprise-wide cost-reduction and simplification effort as a way of responding to rapidly changing technologies and new competitive threats. The initiative was launched with great fanfare and positioned as key to the company’s long-term success. A well-known consulting firm was then hired to identify opportunities for streamlining, and with help from an executive sponsor from the CEO’s team, they set up a project management office and war room.

Over the next two months, the consulting firm and internal staff collected data on spans and layers, benchmarked industry cost levels, and gathered process improvement ideas. When it came time to present the first set of recommendations to the senior team, however, the CEO was out of town meeting with investors – so the discussion was postponed. A month later, the CEO delayed the meeting again due to a customer problem. The next month, the CEO asked the executive sponsor and the lead consultant to meet with each of his direct reports individually to bring them up to speed on the findings. This led to a series of polite discussions and several requests for more data, but no action. Eventually, the CEO suggested that the executive sponsor figure out a phased approach to implementation, starting with one or two areas. This led to a further series of debates with each senior executive – most of whom had strong reasons why this was not the right time for them to restructure their units and take out key people.

You probably get the picture. After six months, the company had accomplished very little other than to run up a large consulting bill and to waste the time of some of its best and brightest staff. Why does this happen?

In this example, the CEO was a conflict-averse individual who wanted his team to “work things out” when there was a problem. As he began to realize that not everyone was in agreement, and that the process of change would involve some battles, he withdrew, and perhaps subconsciously, let the project slowly fade away.

We could just blame the CEO, or any senior manager in a similar situation, who tries to delegate the implementation of major change. However, when a senior leader is missing in action, the subordinates and consultants who were charged with carrying out the initiative also play a role: They can either reinforce the hesitancy of the senior leader or try to do something about it. The reality is that senior staff people and experienced consultants often continue to collect more data, have more discussions, prepare more reports, and make more presentations – without calling a halt to the process, confronting the boss about his or her role, or suggesting an alternative way of proceeding. It’s like shadow puppet theater with everyone playing his or her role but knowing that nothing will really change.

In this case, the executive sponsor and the consultants knew the CEO was conflict-averse and receding to the background, but they still played along as if the CEO would eventually step up and intervene. Alternatively, they could have either halted the project or scaled it down to something more manageable as a test case. But by taking the path of least resistance, they just reinforced the dynamics of the executive who was missing in action.

Making major change happen in any company isn’t easy. But when senior executives delegate what should be their responsibilities – and staff and consultants let them get away with it – the chances of success are pretty slim.

When to Make a Promise to Your Boss (and When Not To)

Bending over backward to honor a promise may not do you much good, according to new research from Ayelet Gneezy and Nicholas Epley. The duo tracked three types of promises — "broken ones, kept ones, and then ones that were fulfilled beyond expectations" — and found that overdelivering on promises doesn’t get you much of a boost in satisfaction. Epley says this is because a promise is similar to a verbal contract: The expectation is that you will or won’t fulfill it. However, when someone hopes for something that isn’t explicitly promised, exceeding expectations is beneficial. "If you can guarantee an outcome, you’ll make your customers (or bosses) happiest when you promise it," suggests Businessweek's Claire Suddath. "But if you’re not sure you can do it — or if you think you can do it even better — you might not want to promise anything and surprise them instead."

Not Good at All Google Finally Discloses Its Diversity Record, and It’s Not GoodPBS NewsHour

Google released its global workforce numbers, revealing that 70% of its employees are men, a number that increases to 83% and 79% if you look only at tech jobs and leadership roles. Two percent of Google employees are black. The NewsHour reports that these stats seem slightly more lopsided than other tech companies’, though an analysis by Mother Jones shows a pretty sad demographic profile at the top 10 Silicon Valley firms, particularly among executives.

There's something to be said for the company’s forthrightness in making its numbers public — Google's Laszlo Bock notes that "all our diversity efforts, including going public with these numbers, are designed to ensure Google recruits and retain many more women and minorities in the future." But some, like Vivek Wadhwa, "don’t buy its excuses." Wadhwa has a series of recommendations to move the needle. He recommends revamping job descriptions, changing recruitment tactics, including women on hiring teams, and focusing more on competencies than credentials.

Social Media Gets PhysicalCoke Designs a Friendly Bottle That Can Only Be Opened by Another BottleAdweek

The Colombian office of the Leo Burnett ad agency has designed a plastic Coke bottle with a cleverly engineered cap that can be opened only when it’s fitted together with another Coke bottle’s cap and twisted. So you have to find a partner to have one (and buy two at a time). Maybe even cleverer is the market that Leo Burnett targeted to introduce it — a group with a strong need (and a perfect opportunity) to socialize: college freshmen. Likely inspired by the sharable Coke can created last year by Ogilvy France and Ogilvy Asia-Pacific, this latest physical incarnation of social media has the obvious advantage of doubling, rather than cutting in half, potential sales. You can judge for yourself the creativity emanating far from these agencies’ U.S. home bases in the epic 90-second spot. —Andrea Ovans

Go Big or Go HomeThe Cold Logic Behind Elon Musk’s $5 Billion Gigafactory Gamble Quartz

You have to hand it to Tesla's Elon Musk: He does plan ahead. Although many past forecasts for electric-car adoption have missed the mark — China, for instance, will probably fall short of having 500,000 electric cars on the road by 2015 — Musk is betting heavily on the rapid rise of battery-powered vehicles. He's building the world’s largest lithium-ion battery plant, a "gigafactory" capable of making enough battery packs to power half a million electric cars annually. That’s four times the number of electric cars sold globally last year.

Of course, powerful forces are working to undermine Musk’s vision: Traditional carmakers are fighting zero-emissions laws, and battery and energy researchers are aiming for breakthroughs that would make the gigafactory’s batteries obsolete. But if Musk is right, his production facilities will bring down the cost of batteries by 30%. And because batteries are the single most expensive component in electric vehicles, that would be a big step toward his dream of a mass-market Tesla car. —Andy O'Connell

The Cost of TransparencyOptimal Disclosure: Why Firms Need to Balance Hard and Soft Information Knowledge@Wharton

In corporate finance, transparency and disclosure are good things, right? And the more transparency and disclosure the better? Yes — but. When lawmakers and regulators demand disclosure, the kind of information they’re looking for is hard data — revenue, sales, net profits, that kind of thing. Research by Alex Edmans and Mirko Heinle of Wharton and Chong Huang of the University of California Irvine suggests that when executives have to disclose hard data, they lean toward making moves that improve short-term profitability, sometimes to the detriment of the company’s long-term health.

"Since rules can only stipulate the disclosure of hard information, and not soft, they change the relative weight of hard information versus soft information," Edmans says. "Then managers are going to take actions to boost earnings at the expense of long-run intangible value." Foreseeing steadily escalating calls for disclosure, Edmans has a word of warning for those who establish financial rules and regulations: "When policy makers are thinking, "Do we want even more disclosure?' they should think, 'Well, there is a cost to that.'" —Andy O'Connell

BONUS BITSThree on Amazon

Why I’m Ditching my Amazon Account (Reuters)

Publishers' Deal with the Devil (stratechery)

How the Amazon-Hachette Fight Could Shape the Future of Ideas (The Atlantic)

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers