Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1413

June 9, 2014

A Plan to Revitalize Greece

Greece is finally showing signs of recovering from its 2008 crash. However, as much as macroeconomic reforms are needed, the future of the Greek economy will be determined by its competitiveness, which concerns costs, but is also measured by innovation.

In that regard, Greece finds itself at a crossroads. It can improve its competitiveness by reducing costs in its traditional sectors, such as tourism, agriculture, and trade. Or it can aim higher – by laying the groundwork for higher value-added goods production.

The key to such a change is developing an innovation-oriented industrial structure and a well-functioning innovation system. This is going to be a considerable challenge.

Currently, the annual expenditures for research and development (R&D) amount to 0.67% of Greece’s GDP. Other Eurozone economies invest four times as much in relative terms, around 2.5% to 3% of their GDP.

In the “Innovation Performance Index,” prepared by the European Commission, Greece ranks far lower than any other Eurozone country. This is unsurprising given that the traditional sectors of the Greek economy are far less dependent on R&D. To get ahead, Greece’s business environment has to change and become much more open to innovation.

According to the 2014 edition of the World Bank’s “ease of doing business indicator,” Greece ranks 72nd out of 189 countries. Despite some improvement, Greece still has an overregulated legal framework that puts substantial burdens on entrepreneurs. Requirements for licenses, permits, and reporting remain excessive. Key agenda items – such as investor protection, the enforcement of contracts, and an efficient insolvency regime – remain unfinished. And the OECD’s most recent report on Greece identified 555 regulatory restrictions that, if lifted, would create major incentives to re-dynamize the Greek economy.

Technology-oriented firms face further obstacles, which have inhibited the country’s potential innovators since long before the current crisis, often forcing researchers to retract into fundamental research or academia instead of becoming entrepreneurs. Some companies, such as MobileFX, Velti, Globo, InternetQ, and Lykos, remain based in Greece but have chosen to develop their innovations abroad.

If there were ever a time to shed all that superfluous, bureaucratic baggage, that time is clearly now. Making this decision is a matter of national self-interest. The Greek minister of development, for his part, has started the reform process, but he needs strong political support to complete it.

The good news is that there are some hidden assets in Greece, on which the country may build a modern innovation system. The first are the research centers of excellence, such as the Demokritos Center in Athens, FORTH in Crete, and CERTH in Thessaloniki.

A second hidden asset is the huge number of top Greek researchers working outside the country. Greece is the only Eurozone economy “exporting” more scientists to other European countries and the United States than it is able to keep at home.

The third asset is the considerable number of small but innovative companies all over Greece that have developed new ideas. Though many leave the country, some firms have remained despite the adverse innovation environment. For instance, Raycap has developed solutions that protect telecommunications, power, and transportation networks. Systems Sunlight produces complex battery systems. And Tropical SA is focused on hydrogen and fuel cell technologies. Greece simply needs more of these businesses.

Greece’s fourth asset is its attractive climate and the overall quality of life. In an increasingly global race for the best talents, the quality of life outside the lab has turned into a crucial success factor, which should enable Greece to become a global attractor for talent.

Given the country’s strengths and weaknesses identified above, one point is paramount: The political arena needs to create a vision of innovation for the country. A coherent innovation policy, designed to unlock Greece’s hidden assets, will require five key steps:

Strengthening efforts to cut red tape. Reducing administrative hurdles to entrepreneurial activities is very doable in principle. Greece should aim to realize permanent business registration within one day. And it ought to focus on becoming one of the top 25 economies in the World Bank indicator when it comes to “Ease of Doing Business.”

Investing in applied research centers of excellence (along the lines of Boston, California, Oxford, EPFL, or Fraunhofer), and reorganizing research institutes and universities into clusters. New institutes should help to consolidate the existing web of applied research and universities, which when organized into geographic clusters, create greater efficiencies as well as research cross-fertilization. This needs to be done in those sectors where Greece shows a tendency for specialization, specifically in the areas of quality of life, information and society, and sustainable energy. Building scientifically competitive research campuses will help close the gaps in the innovation chain and attract talent, both of Greek and non-Greek origin.

Developing networks between research and business, and engaging all partners to cooperate in the innovation chain. High-quality science needs to align with technology-based entrepreneurship.

Developing politically independent research organizations by providing research grants based only on merit and research quality. To unlock Greece’s hidden assets, universities and research institutes must become independent from any political influence. This requires that they are able to autonomously decide on their budgets.

Extending that network to the Greek business and research diaspora. The Greek diaspora, although very strong, is currently not treated as a potential economic asset. Most measures aiming to close the gaps in the innovation chain can be supported with a target-oriented diaspora policy. For instance, dual academic appointments in Greece and abroad can stop the current brain drain and allow the circulation of ideas between countries.

Whether or not the transformation of Greece into a real innovation hub becomes reality will take more than investments into R&D and into research centers. Vested interests must be overcome, and Greek society must embrace change for a better future. That requires a new openness, not just regarding the independence of research activities, but also regarding a constant exchange between the worlds of research and entrepreneurship in all kinds of directions.

In that sense, the Greek innovation task is just one version of the country’s biggest challenge: using this profound crisis to reinvent itself and to cast the unproductive practices of the past overboard.

June 6, 2014

Customer Complaints Are a Lousy Source of Start-Up Ideas

Consider this situation. A good friend of yours calls you one day to pick your brain about an innovative business idea. He’ll only consider pursuing this opportunity if you give him a positive review. This particular friend is unemployed at the moment, and he plans to invest most of his savings in the venture. So there’s a lot at stake for him.

On what grounds would you base your opinion? Would you trust your gut? Your past business experience? Look for examples of similar ideas you’d seen elsewhere or that have worked in the past? Try to find parallels from other industries that might also work in this case? Maybe you’d start by digging into a ton of data to confirm or refute your true opinion about the venture.

Clearly, there are many ways to evaluate an innovative business opportunity. But at the end of the day, whichever way they do it, people considering a new business idea usually try to fit it into one of these three broad categories.

1. “Good idea! Nobody does that.”

2. “Go for it! Customers are complaining all the time that no company’s product or service is good enough at this.”

3. “The idea might be good, but there are very powerful competitors in his industry doing a terrific job.”

Before you continue reading, ask yourself which of the three options you’d want your friend’s idea to fall into. That is, which one would seem to represent the most-promising alternative? It turns out that disruptive innovation researchers have empirically measured the odds of success in each of these situations, and their findings may not be what you expect. Here’s what they’ve found, and how they explain their results when they look at them through the lens of disruptive innovation theory.

“Good idea because nobody does it”: Innovations that do things that have never been done before create new markets (thus the term “new-market disruption”) and so are necessarily aimed at people not currently in that market – that is at “nonconsumers.” Quicken software, the Sony Walkman, eBay, the University of Phoenix, and Rent the Runway are a few examples. Studies on disruption indicate that, when done right (that is when an innovator fulfills an important customer need with a profitable business model), new-market disruptions have a whopping 60% chance of being successful in the marketplace. That becomes less surprising when you consider that they face no competition; that initially the market is often too small to tempt incumbents; and that their business models are often more modern, using better technologies to fulfill customer needs in a much better way than currently available substitutes.

“Go for it! Customers are complaining all the time that no company’s product or service is good enough at this.” Common sense would tell us that a customer complaint is an opportunity to start something new that will finally meet the demands of frustrated consumers. But disruptive innovation theory tells us otherwise about these “underserved consumers” — these customers who want better products and are willing to pay for them. The type of disruptive business that is built around an underserved consumer is a “high-end disruption,” and it is very hard to pull off since such opportunities are very attractive to incumbents.

Generally speaking, an innovator needs to come to market with an entirely new, incompatible business model that uses a different distribution channel for the barriers to emulation to be high enough to keep deep-pocketed competitors at bay. When high-end disruptions do take off, they win big. You can see that in such examples as Whole Foods Market, Tesla, and Geox. But disruption studies indicate that only 4% of high-end disruptions succeed. A customer complaint might be an opportunity, but 96 times out of 100 it’s an opportunity for established firms.

“The idea might be good, but there are very powerful competitors in his industry doing a terrific job.” Surprisingly enough, one of the cruelest fates an established company can meet arises from doing a terrific job. When established firms perform well, and improve year after year for a number of years, they eventually improve so much that they end up creating “overserved consumers.” That is, they focus their resources on improvements that consumers do not want and will not pay for. Overserved consumers represent fertile ground for the classic low-end disruptor. These are upstarts that can come to market with a radically lower-priced offering by eliminating some expensive features that consumers undervalue and substituting other, less costly features that consumers value highly but incumbents have overlooked (or are not interested in pursuing since these features generally produce lower margins). The three most often overlooked features are related to making the product simpler, more affordable, and easier to use. When done right, low-end disruptions have a 40% chance of success. Netflix, Curves, Dell, Xiameter, and Glasses Direct are examples of low-end disruptions.

Research indicates that the new-venture failure rate today is above 80%. Disruptive innovation, applied strategically, can significantly lower these numbers. So the next time your friend comes to you with a new venture idea (or you’re thinking of launching one of your own), ask yourself how you will evaluate that opportunity. Will you trust your gut? Or will you look at the chances of three clearly identified patterns of success?

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

Start with a Theory, Not a Strategy

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

Google’s Strategy vs. Glass’s Potential

A Little Perspective on Amazon’s Book Business

The contract battle between behemoth Amazon and Goliath Hachette has become a full-on Thing, with pundits pontificating on anti-trust, bemoaning the future of books, and even trotting out a corporate anti-bullying law from the 1930s as a remedy.

Amazon may be losing the PR battle right now (scorn Stephen Colbert and “Robert Galbraith” at your own risk), but Hachette is laying off staff and reports suggest that the standoff is damaging its business.

Boycotts may hurt Amazon, but how much? To put the stakes in perspective, we’ve visualized a worse-than-worst-case scenario for the Seattle company. What would happen to Amazon’s annual revenue if its U.S. book business disappeared entirely tomorrow?

Get Over Your Fear of Conflict

Most of us have some resistance to conflict. Instead of addressing issues directly, we try to be “nice” and end up spending an inordinate amount of time talking to ourselves or others — complaining, feeling frustrated, ruminating on something that already happened, or anticipating something that might happen. These conversations usually sound something like this:

“My colleague interrupted me again. We’re supposed to be leading this effort together and this is his way of showing he’s the boss. He just makes me look bad in front of the team. I’ve been replaying it in my mind over and over again.”

“Someone has to tell my direct report that his bad attitude is affecting the rest of the team, but I’m dreading it. I’ve been thinking about it all day and haven’t been able to get anything done.”

“I know what they’re going to say — that we can’t have more resources due to budget constraints. I’ll probably just give up on this.”

Sound familiar? These are just three recent examples that I heard in coaching sessions with clients.

Here’s the trouble: These efforts to be “nice” can have pretty significant costs. You create relationships that are neither authentic nor constructive. Your health and self-esteem may suffer and you signal that you’re a victim. And your organization loses out as you make compromises with the loudest person in the room, lose the diversity of thinking that’s critical for innovation, or stop producing the best solutions.

Below are five tips I’ve offered clients when they find themselves avoiding conflict:

Recognize that being nice is an outdated strategy. At some point in your life or career, you probably got burned by conflict, and felt shamed or criticized. When that happens, we often decide to be accommodating rather than ever feeling that way again. We choose safety, peace, and harmony over speaking up.

When I ask clients why they don’t want to have difficult conversations, it usually comes down to fear of experiencing those emotions again. Many have an “a-ha” moment when they realize they’re no longer that younger version of themselves; they’re now a more seasoned, experienced person with new skills and know-how. As one client recently put it, “I’m still behaving as if I’m that second-year associate who got shouted-down by the senior partner for pushing back. But I’m now the general counsel of this organization.”

Focus on the business needs. When you avoid conflict, you’re actually putting the focus squarely on yourself. In all three cases above, the clients felt backed into a corner, concerned about how others might perceive them. But it’s not about you.

When I ask clients, “What would the CEO, customers, or shareholders of your organization say about this situation, and what does the business need?” they’re suddenly much more objective and clear:

“The business needs me and my peer to be a united front.”

“This direct report has a lot of potential and if I could coach him to use a more positive style, he could make a great contribution.”

“We need to discuss the vision of what we’re trying to achieve and the resources it will take to make that possible.”

Take the focus off you and your fear and concentrate on what the business needs.

Speak objectively and make requests. Use observations, not labels. For example, in the case of the direct report, he’s likely to be defensive if you say, “I need to talk to you about how negatively you come off in staff meetings.” Instead, talk about what you observed: “I noticed in the last two staff meetings that when the COO got to the topic of the change initiatives, your body language changed and you reacted quite strongly. I’d love to discuss how you could share your concerns in the most productive way possible.”

Include a request for the behavior that would support the shared business goal. In the case of the interrupting colleague, you might say, “In the last team meeting, I noticed that we were interacting with each other in a way that may be throwing the team off. To keep the team on track, it’s important that we appear as a united front. Can we determine what role we’ll play in the meetings in advance or agree on some non-verbal signals when it’s time to pass the baton?”

Keep a calm demeanor. People who shy away from conflict often assume that it has to look aggressive, overbearing, or disrespectful. It doesn’t. You can — and should — be yourself and remain approachable, non-judgmental, and calm in these situations by being clear, focusing on the business needs, and making a request to ensure the business goal is achieved.

Start with baby steps. Like any muscle you build, it takes practice and repetition before you can ratchet up your abilities. Start with easier situations first and address the conflict retrospectively (it can be hard to do it in the moment at first). But institute a statute of limitations whereby you cannot ruminate, fume, or carry on unproductively beyond 48 hours. During that 48 hours, focus on being more conscious and self-aware. Ask yourself: What are my triggers? What caused my anxiety and why does this feel personal? What does the business need from me in this situation? What request am I not making? Then, take action.

Gradually, each of these new experiences will help you reframe conflict from something you dread, to something that — when properly embraced — can help move the business forward.

Focus On: Conflict

When an Inability to Make Decisions Is Actually a Fear of Conflict

The Best Teams Hold Themselves Accountable

Win at Workplace Conflict

Managing a Negative, Out-of-Touch Boss

You Probably Can’t Tell the Difference Between a Bot and a Person

Ah yes, those pesky Twitter bots. While it may seem fairly obvious to you whether a follower is a real person or not, Carlos Freitas and other researchers created 120 socialbots and found that a significant proportion "not only infiltrated social groups on Twitter but became influential among them." Only 38 were suspended by Twitter and more than 20% picked up 100 followers or more. They also received similar or higher Klout scores than "several well-known academics and social network researchers" and were the most successful when generating synthetic tweets (rather than just retweeting).

This suggests that "Twitter users are unable to distinguish between humans and bots," which is concerning in light of the proliferation of services that measure interest and opinion on social networks. "The worry," according to the Tech Review, "is that automated bots could be designed to significantly influence opinion" about such things as politics and products.

Mostly by Arguing How Greylock Partners Finds the Next FacebookNewsweek

When the CEO of Sprig, a start-up focused on meal delivery, finally made it to the boardroom of the VC firm Greylock Partners to pitch his business model, everyone argued about it. But that was a good thing: Intense debate over conflicting views is an accepted part of the process at Greylock and occurred regularly when the company made its biggest and most successful bets on Facebook, Pandora, and Airbnb. Katrina Brooker describes this process and many other inside details in her anatomy of the firm, which is made up of former engineers and start-up founders and is seen as the golden ticket for any fledgling company in Silicon Valley.

And while the competition among VC firms to fund the next big thing is fierce, Greylock has an advantage, as Medium’s Ev Williams notes: "The thing I heard, time after time, was David [Sze, a Greylock partner] was always trying to do the right thing for the entrepreneur." This includes having an in-house recruiting firm to locate the best engineering talent for the start-ups it funds, a huge boon in a wildly competitive job market.

The Comfort of CrowdsAre Smartphone Users the Missing Link in Building Efficiency? Greentech Media

Have you ever been too cold at work and wandered around looking for a thermostat, only to realize that your workplace climate is controlled by unseen microchips that think they’re a lot smarter than you are? They aren’t smarter, of course — you’re the best judge of your own comfort, just as you’re the best judge of your lighting levels. In this piece from Greentech Media, Jeff St. John describes a start-up, Crowd Comfort, whose software allows human beings to talk to their buildings via smart phones about such things as heat, light, and air flow.

Using an app, employees can signal where they’re located in a building and report on their comfort or discomfort. Because they remain anonymous, they have the freedom to report how they really feel. (First the physical climate, next the emotional climate? Wishful thinking.) A big selling point, the start-up hopes, is the energy-saving potential: If you’re a facilities manager, you can lower the temperature by 1 degree and see whether anyone reacts. If people are still comfortable, you’ve saved your firm some heating costs. Buildings consume three-quarters of the all the electricity used in the U.S., so the energy savings could be significant. —Andy O'Connell

George Washington Approved! Spy vs. SpyThe New Yorker

Fellow history nerds, rejoice: James Surowiecki has written a delightful piece on economic espionage throughout history. In particular, he argues that China's recent theft of trade secrets from the United States probably sticks in America's craw because "that's pretty much how we got our start as a manufacturing power, too." He cites examples like Samuel Slater's knowledge of Arkwright spinning frames, Francis Cabot Lowell's infiltration of British mills, and the actions of America’s "most effective industrial spy," Thomas Digges, who was lauded by George Washington for his "activity and zeal." Recently, Surowiecki notes, the U.S. has been all about enforcing stringent intellectual-property rules. But "as our own history suggests, the economic impact of technology piracy isn't straightforward," with examples of patents and trade secrets both helping and hurting innovation.

Above It AllPatek Philippe Crafts Its FutureFortune

The 175-year-old Swiss watchmaking company Patek Philippe gives a whole new meaning to “high end.” It floats in a cloud of superlatives: Last year the company unveiled its most complex wristwatch to date, a timepiece that has 686 parts, is encased in 18-karat white gold, sports a double dial with a cloisonné face, and costs more than $1 million. The company holds the record for a watch sold at auction — $11 million. Owners of Pateks have included Queen Victoria, Pope Pius IX, Joe DiMaggio, Leo Tolstoy, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Andy Warhol, Eric Clapton, Jack Welch, and Vladimir Putin.

Yet Patek is also a company of contradictions — while it maintains a reverence for its past, vowing to service any watch dating back to 1839, the company remains focused on the future: In its R&D department, 80 engineers, technicians, and drafts people develop new movements and functions using such technologies as 3D printers. This piece by Stacy Perman, excerpted from a new book, touches on a few modern-day challenges facing the company, such as smart watches, but it’s hard to take those threats seriously. Somehow Patek seems to exist on a different plane from the rest of this grubby world. —Andy O'Connell

BONUS BITSViews from Modern Work

Opportunity's Knocks (The Washington Post)

Friends Without Benefits (The Baffler)

How the Recession Shaped the Economy in 255 Charts (The New York Times)

What Big Data Needs to Do to Grow Up

We are in an Information Revolution — and have been for a while now. But it is entering a new stage. The arrival of the Internet of Things or the Industrial Internet is generating previously unimaginable quantities of data to measure, analyze and act on. These new data sources promise to transform our lives as much in the 21st century as the early stages of the Information Revolution reshaped the latter part of the 20th century. But for that to happen, we need to get much better at handling all that data we’re producing and collecting.

Consider the more than $44 billion projected by Gartner to be spent on big data in 2014. The vast majority of it — $37.4 billion — is going to IT services. Enterprise software only accounts for about a tenth.

The disproportionate spending on services is a sign of immaturity in how we manage data. In his seminal essay, “Why Software is Eating the World,” Marc Andreessen pointed out that for each new technology wave, the money eventually shifts to software. Software spending represents an industrialization and packaging of work that would otherwise happen manually, as one-off services, within each organization. As markets mature, more of the processes move to partners and other providers, so the industry leaders can spend their time and energy on high-value processes that contribute to their competitive differentiation. Software is part of a broader ecosystem that lets businesses focus on activities that are core rather than context. Core, in Geoffrey Moore’s definition, is what a business’s customers cannot get from anyone else; context is all the other stuff a business needs to get done to fulfill its commitments.

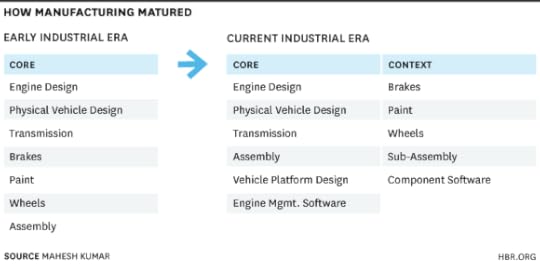

To understand what that path to maturity might look like for big data, it’s helpful to look at another, similar transformation. Data is the raw material that we attempt to turn into useful information. We can learn something from the manufacturers who turned raw materials into achievements as complex as automobiles.

The earliest automobile manufacturers were “vertically integrated,” which is to say they pretty much did everything themselves. Contrast that with today’s automobile manufacturers, which source parts from a global marketplace of independent suppliers. A manufacturer like Ford might have more than a thousand Tier 1 suppliers.

By calling on a rich ecosystem of industrialized products and services, automobile manufacturers can focus on the high-value, core activities that differentiate their products while driving down the total costs of production. This shift has led to a dramatic increase in automobile capabilities, without a corresponding increase in costs.

Over the years, the automobile industry has embraced numerous innovations to achieve this transformation. These include:

Standardization: From parts to specifications and protocols, standardization is the essential first step in building a mature ecosystem.

Quality testing and controls: Standardization also includes the concept of quality controls, testing protocols, and acceptance testing to enforce adherence to standards.

Design for manufacturing/design for assembly: Integrating manufacturing and/or assembly processes into product design has reduced manufacturing and assembly costs at the source.

The shift from vertically integrated manufacturing (doing everything in-house) to integrated and collaborative design, manufacture, and assembly has enabled us to build larger, more advanced and complex goods than ever before. It has reshaped our communities and lives.

Can we make a similar shift with data?

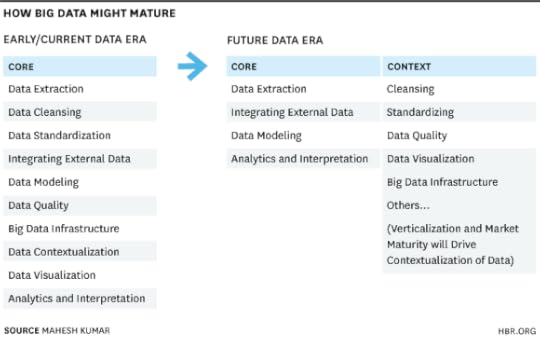

When businesses try to manufacture real insight and value from raw data, most are like the early manufacturers, doing nearly everything in-house. Despite recent technological advances, the task of turning data into information is characterized by vast inefficiencies.

That’s why we see such a huge spending on services — we haven’t figured out how to automate and industrialize different parts of the data processes. We treat nearly every data-related task as a high-value, core process, for which we must spend on specialized services. It’s all core, no context.

Until we find ways to start treating some of the data tasks as contextual — to industrialize those processes — then we will be limited in what we can accomplish with data.

To industrialize these processes, we will need advances comparable to those that have occurred in manufacturing, including:

Data standardization, particularly industry-specific standards and taxonomies.

Data quality processes, such as advances in data integration/cleansing and quality control.

Third-party data services (i.e., data clouds or “industrialized data services” in Accenture terminology) that enable data sharing and exchange at scale, between applications and organizations.

Vertical data applications that understand all aspects of data relating to a specific task (e.g. IT Security).

Data assembly, meaning dynamic assembly of raw data, processed data, and contextualized data.

Industry cooperation in sharing the data that is “context” and common to all players.

With the ability to standardize data (akin to parts standardization in manufacturing) and use those standards in multiple applications, companies can begin to partner, outsource and collaborate on much of the work of involving in turning data into insight. The more that companies can share and repeat the context processes around different types of data, the more resources they have to invest in the higher-value, core data processes.

If Your Brand Promises Authenticity, You Better Deliver

Your culture might be positive. Your brand messages might be powerful. But the greatest potential your organization has is the special case when culture and brand are completely aligned. The slightest divergence between them can undermine even the most brilliant (and expensive) marketing campaign.

Imagine: A large coffee chain spends millions on a strong marketing campaign that tells customers everywhere their local café will be just like home. The ads are brilliant, showing a place where I can read and relax, think and work, or just hang out for hours with friends with no pressure to give up my seat just because my latte is long gone. Then imagine if I go there and received a friendly, “Good morning! How can I help you? What would you like?” from a woman with the name badge “Margot.” I order something and hear, “Your drink will be ready in a minute. You’ll find the milk and sugar over there. Have a great day.” As I turn to collect my drink, I see a “friendly” suggestion that I don’t use my laptop during peak hours. In this case I’d end up with two things – a latte and dissonance.

It might be excellence customer service, but it would be nothing like my home. At home people are friendly and familiar, rather than polite, I use my laptop whenever I like for however long I like, and I certainly know where to get the milk. While before their campaign I would have been happy with great customer service, in this case I’d feel a lack of authenticity. I might even feel less attached to this chain that I did before they spent months and millions convincing me of something that wasn’t true… at least not according to my personal experience. On the other hand, if I have an experience that matches and reinforces the brand promise, my connection to this chain is stronger than ever. The leaders’ commitment to not just providing excellent customer service but to actually shaping their organizational culture decides which my experience will be.

People largely make decisions based on their experience. We know that if somebody’s body language is sending a different message to the words they’re saying (“I’m really happy to be here with you today,” said with a flat facial expression) their audience will typically believe their body language (“You are not”, concludes the audience, “Your boss made you come”).Equally, if an organization sends a message that is different from a customer’s experience, that customer tends to believe their experience – and they are likely to feel less positive about that organization than if they had just had a nice enough experience without any brand messages.

Across all industries, organizational authenticity is powerful, and it’s achieved by cultural architects: leaders who ensure alignment between culture and brand. The companies I’ve worked with who do this exceptionally well ensure they have a few simple keys in place:

Recognize that culture can and should change. A powerful culture is not one that is fixed. Too often people think they have a strong culture if they’ve spend decades nurturing the one that’s been ingrained since the firm’s humble beginnings. But strategy changes and culture should change with it.When called in to advise a large transatlantic law firm, I discovered they were fiercely directed by a strategy consultancy (at the end of intensive research into sector changes and their firm) to build true collaboration into their individualistic, competitive culture. If they didn’t, they would simply not be able to sustain their position as a leader in the field. External changes meant the market demanded collaboration, and internal efforts meant clients expected it. Successful strategic changes and a strong marketing team had positioned the firm as offering a seamless service across departments and global locations. If client experiences didn’t match the brand promise, they would not survive. The culture had to change.

Teach others to be cultural architects, too. Leaders throughout the organization need to know what culture really is, that it can be purposefully built, and how to do it. This is something I believe should be in every leadership development program, but rarely is. One executive in charge of “People” or “Talent” (no matter how fabulous they may be) can’t be solely responsible for facilitating the desired culture; it’s the responsibility of every leader to be shaping the organization’s most powerful tool.

Go beyond banner values. Having three positive words written on the wall and across the bottom of marketing materials is not a shared understanding of culture. Meaning comes from the honest conversations and daily behaviors that mean those values are really lived. Not long after one large US bank acquired a Chinese bank, the SVP in charge described to me the challenge they faced when, after the merger, they realized “Customer Focus” and “Customer First” were two very different things in terms of how the bank’s members behaved. Culture is more than banner values.

Put skills second. Use the organization’s culture as the starting point for designing training and development, and upon that foundation then address skills gaps.In the same way that hiring processes send a message to job candidates about that organization, training and development experiences send a message to participants about the organization’s true culture – what it really values and wants to be.

When all organizational members have a shared understanding of the culture and the cultural goals– what it really looks like in practice, what it means and why it’s important to their and the organization’s success, people can take calculated risks, become more creative, and can make decisions on their own without constantly consulting a rulebook.

As I finish writing this I smile, knowing I’m about to experience the impact of an excellent cultural architect who I’ll probably never meet. In a few minutes, when I walk out of the office and go around to my local café, I’ll see Margot. She doesn’t wear a name tag – she doesn’t have to. I know she’ll be there today, because I know she doesn’t go to university on Wednesdays. She’ll make me my regular latte, remembering the soy milk, and ask where my daughter Saskia is today — and then probably cheekily tell me I should stop work and go to the park with my three-year old on this sunny London afternoon. Maybe I will.

Strategy Is Iterative Prototyping

Managers have no way of predicting with any certainty what will happen with respect to an industry and its likely evolution, customers and their likely preferences, a firm itself and its potential capabilities and cost structure, and competitors and their likely responses/actions. We just can’t do it.

One common response to this reality is to ignore the inherent complexity: simplify, analyze, and then make a plan. That typically doesn’t end well, because complexity and unpredictability undermine the plan almost as soon as it is made. A second response is to throw up one’s hands, declare the situation too complicated to make a decision, and adopt an unhelpful interpretation of “emergent strategy,” the modern strategy scourge.

The third approach is to recognize that while the world is complex and uncertain, abdication of choice is not a productive response. This third way treats strategy as prototyping. Prototyping is a tool for progressively shortening the odds of a course of action and minimizing the costs along the way. An organization produces a succession of prototypes to test an idea, gain insights, improve the prototype, test again, gain insights, improve, and so on until the idea is ready for prime time.

The same can hold for strategy. A strategic possibility — a set of answers to the five key questions of strategy (what is our winning aspiration, where will we play, how will we win, what capabilities must we have, and what management systems are required) — is, in fact, a prototype. At first, it is a conceptual prototype. Strategy can be thought of as moving from the conceptual realm to the concrete realm through the process of iterative prototyping.

The first iteration of prototyping involves asking what would have to be true in order for the initial answers to those five questions to be sound and then testing those answers without actually putting the strategy into action. The answers can then be modified and enhanced.

The refined prototype can be tested again, modified, tested again and so on. And with each iteration the tests move further into the realm of action and the marketplace. Aspects of the strategy can be tested by actually doing things with customers — and gaining more understanding to hone and refine the strategy with each iteration.

In fact, the prototyping should never stop. It is ongoing, as you receive new data from the market, your competitors and within your organization. It is better to think of your strategy as not set in stone but rather as the most recent prototype being tested by the latest marketplace experience. That way strategy will never get out of sync with the competitive environment.

Why We Humblebrag About Being Busy

We have a problem—and the odd thing is we not only know about it, we’re celebrating it. Just today, someone boasted to me that she was so busy she’s averaged four hours of sleep a night for the last two weeks. She wasn’t complaining; she was proud of the fact. She is not alone.

Why are typically rational people so irrational in their behavior? The answer, I believe, is that we’re in the midst of a bubble; one so vast that to be alive today in the developed world is to be affected, or infected, by it. It’s the bubble of bubbles: it not only mirrors the previous bubbles (whether of the Tulip, Silicon Valley or Real Estate variety), it undergirds them all. I call it “The More Bubble.”

The nature of bubbles is that some asset is absurdly overvalued until — eventually — the bubble bursts, and we’re left scratching our heads wondering why we were so irrationally exuberant in the first place. The asset we’re overvaluing now is the notion of doing it all, having it all, achieving it all; what Jim Collins calls “the undisciplined pursuit of more.”

This bubble is being enabled by an unholy alliance between three powerful trends: smart phones, social media, and extreme consumerism. The result is not just information overload, but opinion overload. We are more aware than at any time in history of what everyone else is doing and, therefore, what we “should” be doing. In the process, we have been sold a bill of goods: that success means being supermen and superwomen who can get it all done. Of course, we back-door-brag about being busy: it’s code for being successful and important.

Not only are we addicted to the drug of more, we are pushers too. In the race to get our children into “a good college” we have added absurd amounts of homework, sports, clubs, dance performances and ad infinitum extracurricular activities. And with them, busyness, sleep deprivation and stress.

Across the board, our answer to the problem of more is always more. We need more technology to help us create more technologies. We need to outsource more things to more people to free up own our time to do yet even more.

Luckily, there is an antidote to the undisciplined pursuit of more: the disciplined pursuit of less, but better. A growing number of people are making this shift. I call these people Essentialists.

These people are designing their lives around what is essential and eliminating everything else. These people take walks in the morning to think and ponder, they negotiate to have actual weekends (i.e. during which they are not working), they turn technology off for set periods every night and create technology-free zones in their homes. They trade off time on Facebook and call those few friends who really matter to them. Instead of running to back-to-back in meetings, they put space on their calendars to get important work done.

The groundswell of an Essentialist movement is upon us. Even our companies are competing with one another to get better at this: from sleep pods at Google to meditation rooms at Twitter. At the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos this year, there were — for the first time — dozens of sessions on mindfulness. TIME magazine goes beyond calling this a movement, instead choosing the word “Revolution.”

One reason is because it feels so much better than being a Nonessentialist. You know the feeling you get when you box up the old clothes you don’t wear anymore and give them away? The closet clutter is gone. We feel freer. Wouldn’t it be great to have that sensation writ large in our lives? Wouldn’t it feel liberating and energizing to clean out the closets of our overstuffed lives and give away the nonessential items, so we can focus our attention on the few things that truly matter?

People are beginning to realize that when the “more bubble” bursts — and it will — we will be left feeling that our precious time on earth has been wasted doing things that had no value at all. We will wake up to having given up those few things that really matter for the sake of the many trivial things that don’t. We will wake up to the fact that that overstuffed life was as empty as the real estate bubble’s detritus of foreclosed homes.

Here are a few simple steps for becoming more of an Essentialist:

1. Schedule a personal quarterly offsite. Companies invest in quarterly offsite meetings because there is value in rising above day-to-day operations to ask more strategic questions. Similarly, if we want to avoid being tripped up by the trivial, we need to take time once a quarter to think about what is essential and what is nonessential. I have found it helpful to apply the “rule of three”: every three months you take three hours to identify the three things you want to accomplish over the next three months.

2. Rest well to excel. K. Anders Ericsson found in “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance” that a significant difference between good performers and excellent performers was the number of hours they spent practicing. The finding was popularized by Malcolm Gladwell as the “10,000 hour rule.” What few people realize is that the second most highly correlated factor distinguishing the good from the great is how much they sleep. As Ericsson pointed out, top performing violinists slept more than less accomplished violinists: averaging 8.6 hours of sleep every 24 hours.

3. Add expiration dates on new activities. Traditions have an important role in building relationships and memories. However, not every new activity has to become a tradition. The next time you have a successful event, enjoy it, make the memory, and move on.

4. Say no to a good opportunity every week. Just because we are invited to do something isn’t a good enough reason to do it. Feeling empowered by essentialism, one executive turned down the opportunity to serve on a board where she would have been expected to spend 10 hours a week for the next 2-3 years. She said she felt totally liberated when she turned it down. It’s counterintuitive to say no to good opportunities, but if we don’t do it then we won’t have the space to figure out what we really want to invest our time in.

A hundred years from now, when people look back at this period, they will marvel at the stupidity of it all: the stress, the motion sickness, and the self-neglect we put ourselves through.

So we have two choices. We can be among the last people caught up in the “more bubble” when it bursts, or we can see the madness for what it is and join the growing community of Essentialists and get more of what matters in our one precious life.

Why the High Air Fares? Don’t Blame High Profits

In part because of high fuel costs, the global airline industry’s average net profit margin comes to less than $6 per passenger, according to figures released by the International Air Transport Association and reported in the Wall Street Journal. Other factors reducing airlines’ margins are a slump in air cargo and slack growth in high-margin business travel. In response, airlines are purchasing more fuel-efficient planes, slowing capacity growth, and packing aircraft more tightly than ever.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers