Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1429

May 8, 2014

Rethinking Big Data to Give Consumers More Control

The White House recently published two new reports on Big Data and privacy (here and here). The reports outline six policy recommendations, including new legislation to define consumer rights regarding how online activity data is gathered and used.

Not surprisingly, the findings are already viewed “warily in Silicon Valley, where companies see it as the start of government efforts to regulate how they can profit from the data they collect from email and web surfing habits,” according to The New York Times.

Yet by rethinking the use of personal data from the ground up, entrepreneurs can mine new opportunities for experimentation and innovation. This involves focusing on three goals. The first is to design products that shift control of personal data toward consumers (and away from data-brokers and gray markets). The second is to empower people with personal analytics tools to understand the information being collected about them and safeguard their privacy. The third is to create economic value by helping consumers make personal decisions more effectively.

These interlinked objectives aim to give consumers more say over their data and more insight through personal analytics. Here are a few examples of where and how this is already happening:

Making Open Data personally relevant. Over the past few years, once walled-off stocks of governmental big data have been released in the US and UK as part of Open Data, Open Government, and Smart Disclosure initiatives. This trend includes discreetly releasing personal information on-demand to citizens in machine readable formats.

Take the Veteran’s Administration’s Blue Button initiative, which aims to keep patients engaged with their health data outside of hospitals and doctors’ offices. To test commercial opportunities in this environment, a number of entrepreneurs are creating personal analytics tools to help citizens make better decisions about health providers, disease management, and even personal finances related to healthcare.

One prototype enables a patient to use her data to understand the exact dollar amount her policy will cover for a specific procedure. Another aggregates a patient’s healthcare spending data from disparate sources to improve personal decision-making and planning for healthcare spending.

Because of strict HIPAA (medical record) privacy laws, the personal data is not shared with outside commercial interests or data brokers. These tools are producing an intentional and disruptive shift by putting the power of the data in the hands of the patient.

Using APIs to wrest control of your data. A new wave of opportunities has emerged in crafting analytical products that leverage APIs (“application programming interfaces” are specifications on how software programs should interact) to help users gain more control of and insight from their data.

Facebook allows users to download their personal data sets, which include more than 70 different categories of information, from friends to facial recognition data to every IP address you’ve logged onto with your Facebook account. Nevertheless, this effort at transparency can leave users with an overwhelming amount of information and no way to make sense of it all.

A powerful solution to this problem is Wolfram|Alpha’s Personal Analytics app, which uses the Facebook API to help users look for insights in their Facebook data and networks. Users can discover and visualize unexpected patterns in their usage behaviors, like correlations between posting frequency and historical weather patterns. It also helps users quantify how life changes, like starting a new job, affect social network usage.

The upshot is a shift in power and control back toward the user, who can get compelling answers to questions like, “Am I spending too much time on Facebook during weekends and sunny days?”

Users have control over their data in other fundamental ways as well. For instance, the tool follows HIPAA privacy guidelines and is set up to delete all personally identifiable data after one hour; however, users can opt-in to become anonymized “data donors” to support the research efforts.

Developing personalized choice engines. A third opportunity involves creating “mashup” services combining the two areas described above: governments making citizen data available in machine readable formats and social sites making personal data available to users via new apps that leverage APIs. This combination of open government data and social learning works differently than many of the apps you use now, which may rely solely on voluntary user reviews or marketing data.

For example, Work+ is a mobile app that links New York City data (information on libraries and coffee shop seats) with Foursquare (location and mapping data) to help independent and traveling workers find a suitable workspace on a particular day.

Rather than relying on chance to find an available table with WiFi and an electric outlet, this personalized “choice engine” allows you to be analytical in selecting the right spot and in tracking time to prepare for a nearby client meeting.

Say you want to grab dinner after the client meeting. Don’t Eat At___ is another mobile tool that links Foursquare’s location capabilities with New York City restaurant inspection data. The personal choice engine pings you with just-in-time notifications when you check into an eatery that has been flagged for violations or shut down. The power of Open Data and personal data analytics on behavior (entering a flagged restaurant) is put entirely in the hands of the user to facilitate an informed “no-go” decision. It works almost as the inverse of a location-based marketing offer, which might’ve incentivized you to go to the same restaurant. With Don’t Eat At___, the analytical asymmetry favors the consumer rather than the anonymous marketer.

Don’t Eat At___ also has stringent privacy policies in place and collects the absolute minimum amount of information necessary to improve a specific “go or no-go” decision. For instance, when you disconnect, Don’t Eat At____ deletes the two tidbits of personal information it collected — your Foursquare ID and mobile number.

The realization that we’re only on the brink of this new phase of technology adoption should accelerate the drive to radically rethink personal data, as suggested in the White House reports. And soon, most data will be generated by sensors rather than by smartphones and PCs. Analysts estimate there will be 20-30 billion data-generating sensors by 2020, many of which will gather personal data from our homes, cars, and wearables. This Internet of Things increases the need for entrepreneurial solutions that safeguard privacy while empowering consumers to make analytical decisions that improve their health and everyday lives.

This Just In: Sunspots and Planets Shown to Predict Stock Market

Struck by the large number of studies showing that bumps and dips in the stock market can be predicted by such factors as interest rates, credit spreads, dividend yields, consumer sentiment, and cold weather—despite economics Nobel laureate Robert C. Merton’s description of any attempts to estimate assets’ expected return as a “fool’s errand”—Robert Novy-Marx of the University of Rochester set out to see what other market “predictors” he could find. Using the same rigorous statistical methods that underpin all those studies, he found several such predictors, including sunspots and the relative positions of the planets Mercury and Venus in the sky, he writes in a straight-faced article in the prestigious Journal of Financial Economics. (In a footnote, he hints that the weakness in such “prediction” findings is the standard assumption that there’s a simple linear relationship, consistent over time, between these random portents and stock returns.)

Midsized Firms Can Survive a Cash Crisis

Operational meltdowns can devour a midsized company’s cash. Without adequate outside capital, a financial hemorrhage can escalate to a liquidity crash, an ugly moment when no one gets paid. At such a time, company leaders must relentlessly focus on one thing: unearthing cash and holding onto it. Not growth, or even profits.

When start-ups run out of money, they often solve the problem with credit cards or a quick infusion of venture capital. But midsized companies typically need millions of dollars to survive. If they don’t receive it, hundreds of employees and their families suffer, as does the larger ecosystem of customers and suppliers. Large companies rarely face this growth killer since most of them maintain deep cash reserves, have access to the financial markets, and possess the financial discipline to react long before a crash.

Midsized companies need to be far more cash-conscious — even penurious — when their markets go sour. The story of MBH Architects, a northern California firm that designs retail stores, conveys an important lesson on how to survive such a cash crisis. And crisis it was in 2008, the same year the U.S. economy (especially the real estate market) fell off the end of the table.

Dennis Heath and John McNulty founded the Alameda, Calif., firm in 1989. By 2007, they had a staff of 205 and revenue of $26 million. Feeling flush about their current and future prospects, they moved the firm to a nicer headquarters, borrowing $3 million to spiff it up. Then, the great downturn hit. Retailers halted construction on new stores and shuttered underperforming ones. By the end of 2009, MBH’s revenue had nosedived 83% and Heath and McNulty had to lay off three-quarters of their staff.

Nonetheless, the company found a way to survive and even bounce back (more on that later) by taking four actions:

Keeping an emergency cash hoard. Owners of midsized businesses should build a financial cushion outside the company in case the coffers start running dry. The founders of MBH Architects had done this for two years before the Great Recession hit. In 2006 and 2007, the partners earned big bonuses. Rather than spending on yachts and second homes, they saved most of those earnings for a day they hoped would never come. But when it did, they were able to loan MBH a combined $1 million during the firm’s liquidity crisis in December 2008. “Without that money, we’d have been gone,” said firm controller, Oli Mellows.

Mastering the numbers. Many midsized companies maintain woefully inadequate general ledger information. To use a different company example, one growing financial services firm’s new CFO learned this in 2004. The financial reports his CEO showed him looked rosy: Revenue had doubled to $200 million and profits were $20 million. But nonetheless, the company was low on cash. The CFO couldn’t understand why. After three months of pre-audit investigation, he found material errors in the financial statements and revenue recognition problems. Cash revenues were indeed $200 million for the year, but the correct GAAP net revenues were only $30 million and profit was $2 million. He delivered a financial restatement to lenders and investors and created a detailed monthly and three-year forecasting model based on historical data. That enabled the company to find a new lender who refinanced $25 million in bank debt. It also helped the company fund a key acquisition. Four years later, the firm reached $400 million in legitimate revenue and strong profitability.

Cutting fast and precisely. To keep a finger on the financial pulse of the business, MBH Architects’ founders kept one eye on a key metric: the utilization of its people (i.e., the number of hours billed to clients as a proportion of the total number of available billing resources). As utilization dropped, Heath and McNulty made painful staff cuts and put all bonuses on hold.

But a company in the grips of a liquidity crisis must also consider what it might need in a better economic climate. Top management must be very careful about how they downsize the organization. MBH Architects’ Heath and McNulty closed down branch offices, reduced expenses significantly and closed an entire floor of their main office to cut the heating and lighting bill. Some of the staff – including Heath and McNulty — even did janitorial work to keep the bill collectors from the door. But to make sure they didn’t jettison the employees they would need once the economy improved, Heath, McNulty, the other partners, and controller Mellows put all 113 employees’ names on index cards and pinned them up on a conference room wall. They asked: “Who do we need in order to rebuild the firm?” They identified their 50 best people and laid off the remainder.

Maintaining borrowing capacity. If the CFO has a realistic budget, it’s much easier for a midsized company to borrow money. With the $1 million they had saved for their rainy day, MBH’s founders were the first financial backstop. That meant that “patient money” was invested in the firm. Ideally, borrowing should take the form of raising one’s line of credit with the bank every year (especially the good years). It’s far easier to negotiate with your bank for a higher line from a position of financial strength than from one of weakness.

When money gets tight, drawing on the line is better than running your cash down to nothing; that’s the purpose of your line of credit. If you need more money than you have available on the bank credit line, consider outside money in exchange for equity. But be very careful to whom you sell stock. Since most midsized companies are privately held, your new cash needs mean turning to private equity or other private investors. Make sure the payback expectations of your investors are in line with yours. PE firms typically sell portfolio companies in three to five years. VC funds can have 10-year horizons in exchange for an outsized return. If you can’t provide the return an investor wants in the timeframe he wants, things are likely to get ugly. In such cases, don’t take the money.

The MBH Architects story has a happy ending. Due to its fiscal prudence (and a rebounding economy), by 2012, the company was nearly the size it had been in 2007. (2012 revenue was 84% of 2007 revenue.) Profits were actually higher than in 2007. Heath and McNulty had survived the liquidity crash to live another day.

May 7, 2014

Low-Skilled Workers Everywhere Are Getting Squeezed

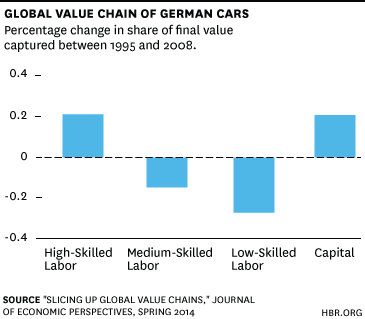

The supply chain for German cars is significantly more globalized than it was a decade and a half ago. In 1995, 79% of the value created in the process of manufacturing a German automobile was captured by domestic firms and workers; by 2008, German companies and workers captured only 66%.

The difference is explained by the phenomenon of “production fragmentation,” in which different firms (and countries) specialize in producing different parts of a final good. German car companies still assemble the final product, but the value chain leading up to that last step has become more fragmented in recent years, and the role of foreign firms has increased.

A recent paper from the Journal of Economic Perspectives looks at the phenomenon of fragmentation in manufacturing and seeks to determine who is capturing value in today’s more global supply chains, as well as who is getting left behind.

To answer those questions, the authors look at the share of value in manufacturing captured by high-skilled workers (those with a college degree or equivalent), medium-skilled workers (high school degree), low-skilled workers (less than high school), and capital. (The latter category includes machinery, factories, and other physical capital, as well as natural resources, intellectual capital like patents, and returns to financial capital.)

This method of accounting looks at the sale price of a product and subtracts the cost of raw materials and other inputs. What is left over is the financial value created by the production process, which is split up between wages paid to workers, and returns to capital.

The paper reveals a shift in who captured value from 1995 to 2008, away from low- and medium-skilled workers and toward high-skilled labor and capital. That trend is visible in the context of German car manufacturing:

Globalization, and the resulting fragmentation of supply chains, hasn’t just shifted the geography of production. It has meaningfully changed the returns to various stages of the production process. As the paper explains it:

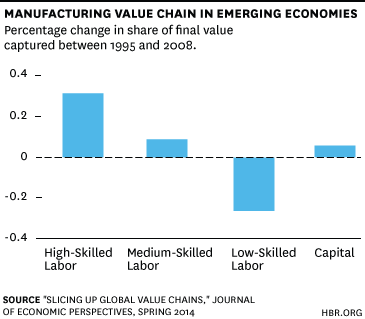

Production processes in manufacturing have increasingly fragmented across national borders, and the change in their factor content was clearly biased towards high-skilled labor and capital. This pattern was not only found for activities carried out in high-income countries, but also in emerging economies.

It’s no secret that in developed economies, high-skilled workers are leaving their low-skilled counterparts behind. More interesting is the dynamic in emerging economies. Despite the fact that low-cost labor is a source of competitive advantage for many of these economies, the share of value captured by low-skilled workers has decreased in these countries as well:

The bulk of value in emerging market manufacturing is captured by factory owners, financiers, and the like, because these investments are in shorter supply than is the low-skilled labor that complements them. But while capital’s share of value captured did increase between 1995 and 2008, on a percentage-basis it was high- and medium-skilled labor that increased the most.

Behind all of this, the authors argue, is “a pervasive process of technological change that is biased towards the use of skilled labor and capital.”

Less skilled workers in developed nations may be losing jobs to those in developing ones, but ultimately both groups face the same challenge. No matter where a product is assembled, high-skilled labor and capital reap the highest returns.

The Case for the 5-Second Interactive

Watching a “cold read” of a data visualization is revelatory. Try this: Hand some friends a printout of an infographic and ask what they think. Then, watch them. People’s eyes will dart, their jaws will clench. Sometimes they will move the paper around, as if meaning will emerge at just the right angle. Loose bits of internal dialogue sneak out: OK, what does that bar — right, got it. For some, defiance takes over if meaning eludes them: What am I looking at? Why is it green? I don’t get it. One colleague of mine grabs the paper — possessing it seems to be part of making sense of it — and then takes a deep breath, seemingly preparing for a mental fight.

I have no doubt about the value of data visualization. We don’t need to belabor the fact that visual information rules and that dataviz literacy will be as fundamental a business skill in the future as spreadsheet literacy is today. But this problem with the cold read bothers me. Even reasonably simple visuals seem to spark confusion, and that’s a problem if the goal is to improve understanding and be persuasive with data. I’ve begun actively trying to build graphics that reclaim that mental energy lost to parsing a graphic for what it could be better spent on: actually analyzing data and forming ideas based on it.

This was the first prototype for beating the cold read problem:

You might be asking, That’s it? The entire experience requires three clicks and about five seconds. It generates a stacked bar chart. All I’ve done is deconstruct a chart into three simpler ones, then allowed the user to put it back together at his or her own pace. Nothing’s particularly clever here; the idea behind it is simple: if cold reads of visual information are difficult because users have to make decisions about where to focus, then if you remove as many of those decisions as possible, users will require less cognitive work to comprehend the information. I’m betting the five seconds it takes to get through the graphic more than makes up for the amount of work the user would have done parsing a static image that presented all the data at once.

Of course, it’s a dilettante’s hypothesis. I’m no scientist, but I did ask the folks at the Harvard Vision Sciences Lab to weigh in on the idea. The team there said that studies that looked specifically at how our brains process infographics as a whole were limited; most of the research is far more (mind-numbingly more) specific than that — but some themes in the research do seem to support an approach that simplifies visuals, and removes choices for our brains.

Good enough for me. And my method, while not scientific, wasn’t haphazard either. I followed these four basic principles when building this five-second interactive:

Eliminate data whenever possible. This is borrowed from Braess’ Paradox. The actual theory applies to how adding route options in traffic systems reduces overall performance. My simple version is: The more data points you present, the harder you make it for users to decide where to focus and how to proceed.

Explain the data as simply and explicitly as possible. That’s just good editing

Use animation to inform, not decorate. Movement on a screen should help the user make sense of the information, otherwise minimize or eliminate it

Tell a story. I was inspired here by John McPhee, a master storyteller who often employs what I’d call “micronarratives” — a few sentences within an essay that tell a story, often to explain something complex. One such McPhee micronarrative, for example, explained how a log burns; another explained why there’s gold in mountains. Point is, humans like narrative; it helps us engage and deal with complexity, even if the narrative is as small as the one above.

Here’s how those principles were applied in the above chart on Football v. Rugby: The opening scene eliminates more than half of all of the information contained in the source dataset. Data are explained and labeled unambiguously: Ask a question (How long are games?), get an answer (60 minutes and 80 minutes).

Next we add five new pieces of information, but crucially we also remove three — the previous subhed and labels. This lets the user (OK, forces the user to) focus on the most important information: the new data. The animation to expand the new bars over the originals isn’t a design flourish; it’s functional. It explains the relationship between data points. The second bar (how much action occurs) literally fills up part of the first one; it’s a subset. State three repeats this same melody, and the narrative concludes with the full reveal of all of the data. By that point, hopefully, no parsing is necessary. We already get it, and we can spend our time thinking about the meaning rather than trying to figure out the meaning.

We’ve tried this approach at HBR here, and here. I hope it can become a format that’s as natural a component of digital content as static infographics are to print. But I don’t think it’s right for every dataviz. Sometimes, complexity is the point, and some would argue there’s value, even joy, in spending time with complex visuals and discovering as we go. Sometimes we don’t know the answers the data are providing, so we want to spend time coming up with multiple possible interpretations rather than being told what the narrative is. Datasets that allow for user-chosen variables to define the visualization probably won’t work in this model, either.

But for the countless good examples of “here’s the point” data visualizations that stream through Twitter and get social love on the Internet every day, it could be a valuable tool that increases the effectiveness of the visualization by beating the cold read.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

Generating Data on What Customers Really Want

10 Kinds of Stories to Tell with Data

Visualizing Zero: How to Show Something with Nothing

Data Alone Won’t Get You a Standing Ovation

3 Myths That Kill Strategic Planning

In its simplest form, strategic thinking is about deciding on which opportunities to focus your time, people, and money, and which opportunities to starve. One of history’s greatest strategic thinkers, Napoleon Bonaparte summed it up this way: “In order to concentrate superior strength in one place, economy of force must be exercised in other places.” If dead, despotic French emperors are not really your style, Michael Porter said it like this: “The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.”

At the highest level, this usually means deciding to sell off one company in order to buy another one. More often it simply means deciding to move some initiatives to the back burner in order to concentrate the bulk of your resources in a single key area.

Sounds simple enough. Yet, three pervasive myths continue to make strategic thinking an elusive skill set in today’s organizations.

Myth 1: Productivity is the goal.

Productivity is about getting things done. Strategic thinking is about getting the right things done well. The corollary of that truth is that strategy requires leaving some things undone, which stirs up a potent cocktail of unpleasant emotions. When you leave projects undone or only half-completed, you must sacrifice that feeling of confidence and control that comes from pursuing a concrete goal (PDF). You will have to fight through the universal psychological phenomenon of loss aversion that results from saying goodbye to a cherished project in which you have already poured heaps of time and money. You will also have to deal with the social pain and feelings of rejection that come from telling some people on your team that their big idea or entire functional area has been demoted in favor of something else more valuable.

In the face of all that unpleasantness, it is tempting to continue striving for productivity. After all, what’s wrong with being productive?

The problem is that productivity is strategically agnostic. Producing volume is not the same as pursuing excellence. Without a strategy, productivity is meaningless. As Peter Drucker famously said: “There is nothing quite so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.” So the next challenge is figuring out which things are the right things.

Myth 2: The leader’s job is to identify what’s “important.”

Here’s a quick exercise: Make a list of every project and initiative your team is working on right now. When you finish the list, draw a line through all of the things that are not important.

If you’re like 99% of teams, not one project on your list will get crossed out. That’s because every project your team is working on is “important” to someone somewhere somehow. They all “add value” in some vague way. That’s why debating about what’s important is futile. Strategic thinkers must decide where to focus, not merely what’s “important.” Strategic leaders must consciously table some “important” projects or ignore some “important” opportunities.

While productive teams log overtime hours in order to knock out one important project after another on a first come, first serve basis, strategic teams decide which projects will contribute most to the declared strategy of the organization, and put the rest of the “important” projects on hold.

Myth 3: Strategic thinking is only about thinking.

Strategic leadership is not a math problem or a thought experiment. Ultimately, strategic thoughts must yield strategic action. Thorough cost/benefit analyses replete with mesmerizing forecasts, tantalizing linear trends, and 63-tab spreadsheets beautiful enough to make a newly minted MBA weep with joy are utterly useless without an actionable decision. In spite of the uncertainty, complexity, and the ever-present possibility of failure, a strategic leader must eventually step up and make the call about what the team will and will NOT focus on.

Tipping his bicorne cap to this truth, Napoleon once said, “Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide.” Perhaps that’s also why this precious ability to decide is the defining feature of those deemed worthy to hold the highest leadership positions.

Make Your Team Feel Powerful

Research has shown that helping others feel more powerful can boost productivity, improve performance, and leave employees feeling more satisfied on the job. A study conducted by Yona Kifer of Tel Aviv University and published in Psychological Science found that employees were 26% more satisfied in their roles when they had positions of power.

Feelings of power also translated to more authenticity and feelings of well-being, the researchers found. Power made the subjects feel more “true to themselves,” enabling them to engage in actions that authentically reflected values they hold dear. This subjective sense of authenticity in turn created a higher sense of wellbeing and happiness.

And yet Gallup research has found that an astonishing 70% of American workers aren’t engaged or committed to their employers. Gallup estimates the cost of their apathy at between $450 billion to $550 billion in lost productivity per year. I’m guessing those workers aren’t feeling all that powerful.

While it would be great to think we could just repeat a mantra each morning to facilitate these wellbeing-enhancing feelings of power, another global study conducted by Gallup found that among some 600,000 workers across several industries, leadership support, recognition, constant communication, and trust were essential to creating a thriving environment where front-line employees felt they had the autonomy to make a real difference in the organization. In other words, to instill a sense of power in people for sustained engagement you need the support of the entire system.

In contrast, overly structured management-driven empowerment programs that are coupled with continuous improvement initiatives don’t work, according to researchers from the University of Illinois, as employees tend to feel such programs are often forced upon them without their input on the initiatives’ usefulness.

Instead, the researchers found that even the least powerful employees will commit to finding ways to make their organization more efficient if given the autonomy to make decisions and execute the improvement measures they find most useful. Managers are advised to act more as coaches, giving direction and support, and trusting that frontline employees, who are the experts on the ground, know better which improvements ultimately work in the best interest of the organization. The study, by Gopesh Anand, Dilip Chhajed, and Luis Delfin, shows that employees will be most committed to the organization when they feel their day-to-day work environment is autonomous and when they trust leaders to have their back. These feelings of power and the reciprocal trust in leadership in turn lead to proactive behaviors by frontline employees, as they’re likely to take charge in continuously seeking ways to improve their day-to-day work practices that lead to organizational efficiency.

While a company-wide effort of making employees feel autonomous and trusted yields the greatest benefit in employee commitment, managers can start with their own team members. Encouraging others to share their unvarnished views on important issues, delegating and sharing leadership, assigning managerial tasks, communicating frequently, and allowing for mistakes to serve as learning opportunities can all empower employees and develop them into independent thinkers who aren’t afraid to take risks and actively contribute in moving the organization forward.

It isn’t necessary, or indeed possible, to elevate every member of staff to a leadership position. But a good manager can offer choices that lead to empowerment, no title required. While we know that people instinctively crave higher status, M. Ena Inesi of London Business School discovered that agency is just as important. She primed study participants to feel either powerful or powerless. They then had to choose whether to shop at a nearby store with fewer options, or a store that was further away but which offered considerably more options. When participants felt powerless, they craved more choices. The participants who felt powerful, however, were content to have fewer choices. “You can imagine a person at an organization who’s in a low-level job,” Inesi said at the time.“You can make that seemingly powerless person feel better about their job and their duties by giving them some choice, in the way they do the work or what project they work on.”

People need to believe they have a sense of control over their situation, particularly in times of change and uncertainty, or they may adopt what psychologist Martin Seligman at the University of Pennsylvania termed “learned helplessness,” where they basically stop trying. In a similar vein, Harvard psychology professor Ellen Langer conducted research on mindfulness and ‘choice’ and found that giving people choices over their environment actually extended life by years, according to her studies conducted among the elderly in nursing homes.

Tom Peters once said, “Leaders don’t create followers; they create more leaders.” Giving your employees real autonomy and helping them feel more powerful is not only your best chance to buck the trend of disengagement and apathy; it is at the heart of competitive strategy.

The Art of Saying a Professional Goodbye

Saying “goodbye” is one of those activities that seems so simple it hardly requires advance thought — and so endings creep up on us and catch us unprepared. We tend to default to our habitual responses whether or not they’ve been effective in the past. As a result we often miss opportunities to enjoy truly meaningful endings — instead they’re rushed and poorly planned — or we skip over them entirely, casting the old aside as we race toward the new.

But at certain times of the year, such as the graduation season that’s about to begin, we’re compelled to give more thought than usual to endings. And in our work lives, we’re saying goodbye with increasing frequency as well, as more work is conducted in ad hoc teams that assemble for a single project and then dissolve.

As an executive coach I’m constantly in the process of beginning and ending relationships. In my private practice I typically see clients for a period of months, rarely for longer than a year, and in my work with MBA students at Stanford I meet an entirely new group of people every 10 weeks. Between the two there’s a steady stream of hellos and goodbyes in my life. (Because of my academic calendar, the beginning of March is particularly intense in this regard — every year at that time I typically end nearly 20 groups and coaching relationships in a span of 10 days.) It can be draining, but I’ve learned how to manage the process to make it meaningful without being overwhelming. Here are five principles that work for me:

1. Understand your needs. We all have different needs when it comes to ending relationships, influenced by our formative experiences, cultural background, and professional training, and it’s important to understand not only the needs of the other people in the relationship, but also our personal needs. That understanding is essential to crafting an ending that works well for all parties, of course, but it’s also a critical step in determining whether our own needs and preferences are helpful or should be modified in some way. I once rushed past endings, sometimes to avoid the strong emotions they evoked and sometimes simply because I was eager to move on to the next thing. But that could put me out of step with the people around me, and it’s been valuable to challenge my preferences and be more flexible about them to ensure that the experience is fulfilling for others.

2. Mark the occasion. Some kind of formal denotation is essential to an ending, even if it’s simply saying, “Well, this is it.” The absence of a denoted ending leaves a sense of uncertainty that can be highly problematic: Are we really saying goodbye? Just what does this transition signify? What will happen on the other side? The difficult emotions stirred up by endings can make us reluctant to formally mark the occasion, but that’s precisely why we should. Rituals, even simple ones, are important ways to acknowledge and deal with these emotions. I’m not suggesting that we need to mark every ending with a complex ceremonial procedure; that’s not appropriate for every group or relationship. But do something.

3. Share the work. Endings work best when everyone involved has a feeling of ownership and agency in the experience. If at all possible, the people participating should have a degree of choice in the nature, timing, and duration of the activities. This doesn’t necessarily require a collective decision-making process or a unified consensus. Sometimes, that’s simply infeasible. But particularly when we’re in a leadership position or another differentiated role we can feel that it’s our individual obligation to orchestrate the ending. With the best of intentions we can take over the process in a way that leaves others feeling disregarded. We’re probably thinking more about the ending than are the others — and thinking about it sooner than they are — and we may well have a unique perspective that should inform the ending. But the more everyone involved feels a collective sense of responsibility for the experience, the more successful it will be. So if we need to make independent decisions as leaders about the nature of the ending, it’s important that the ending we choose provides the other parties with opportunities to be active participants rather than passive observers.

4. Manage the emotion. Endings are — and should be — emotional experiences. The ability to express and share the emotions that are stirred up by an ending help ensure that an actual ending occurs. In the absence of overt expressions of emotion, we can feel that something important was left unsaid, contributing to a lack of closure and heightening feelings of loss or regret. But again, it’s critical to recognize our differences in this regard. Some people are going to feel more emotional than others, and it’s important to make room for a range of expression. If people feel teary, it should be OK for them to cry — and if people don’t feel teary, it should be OK for them not to cry. Emotion management is a critical function of rituals; by design they heighten our feelings and legitimize a fuller range of emotional responses, while also putting some useful boundaries in place that help us contain those emotions, conclude the experience, and move on.

5. Accept — and prepare for — the letdown. Even when we handle an ending perfectly, it’s common, and healthy, to feel a sense of depletion when it’s truly over. Our reluctance to acknowledge endings can stem from our resistance to these feelings. William Bridges, in his great book Transitions, said that all our endings and beginnings are joined by an “empty or fallow time in between,” and that this “neutral zone provides access to an angle of vision on life that one can get nowhere else. And it is a succession of such views over a lifetime that produces wisdom.” When we rush through this period to avoid the letdown we typically feel after a meaningful ending, we cheat ourselves of this wisdom. We’re better served when we accept the letdown, although this doesn’t mean allowing ourselves to become overwhelmed by it. Instead, recognize that it’s coming and prepare for it. We may need to spend some time alone after an ending, or we may need to connect with other people. We may need some open time on our calendar to look back and reflect, or we may need to keep busy and stay active. There’s no predetermined recipe; the key is simply being thoughtful and intentional about what will allow us to access the wisdom that can be found there, while we make ready to move forward again.

So what does this all mean in practice? Here are some techniques to use under different circumstances.

To end a group experience that has been particularly memorable or emotional:

Gather the group in a quiet place where you won’t be interrupted. Ensure that you have roughly 1-2 minutes per group member for the ritual.

If at all possible, sit in a circle, not around a table. Be deliberate about forming an actual circle and have everyone move a little closer to the center; physical proximity matters.

Put a pile of small objects in the center of the circle, one object for each member. The objects should seem noteworthy in some way, but they need not be costly; I typically use small, polished stones used in flower arranging that sell for $1 a bag.

Tell people that when they feel like speaking they should step to the center, grab an object, return to their seat, and briefly say whatever they need to say to conclude the group. The object is theirs to keep as a reminder of the experience.

Emphasize that everyone will speak, however briefly, and you won’t proceed around the circle but rather each person will speak up when they’re ready.

If you’re a leader or authority figure in the group, don’t go first or last; find an opportunity to participate in the middle.

You can modify this exercise to fit the needs of the group or the occasion. For example, at the end of a one-day workshop I might omit the pile of objects, because it can seem too formal for the event. Or if it’s a group in which some people may be reluctant to speak, I’ll ask the participants to go in order around the circle, which creates just enough social pressure to encourage participation without leading to a sense of overwhelm.

Another ritual that works well in groups in which the members have become close is to ask each member to come up with a question for every other member and to bring each question printed out or written on a separate sheet of paper. (I recently did this with some groups of MBA students at Stanford I’d worked with for six months, and the terrific questions I received ranged from “What makes you good at your job?” to “What’s next?”) The exercise consists of distributing the questions to each member, allowing a few minutes for silent reflection, and then having every member speak to the group in turn. Some people will answer a specific question, some will share themes that emerged in the set of questions they received, and some will simply speak about their experiences in the group.

In concluding one-on-one relationships I find that there’s less of a need for formal rituals because it’s typically easier for two people to talk freely about our thoughts and feelings during an ending than it is when we’re in a group setting. That said, it’s still essential to designate the final conversation as such in order for both parties to prepare and to acknowledge the transition.

If you’re concluding a one-on-one relationship as a leader, I recommend sending the other person some questions to reflect on before your final conversation. This will help them clarify what they’re taking away from their work with you and will generate valuable feedback that you might otherwise miss out on. Here are some suggestions:

What’s been most helpful to you about our work together? How has my style as a leader contributed to these aspects of the process?

Are there any ways in which our work together could have been more useful to you? Are there any ways in which my style as a leader was unhelpful for you?

To be as effective as possible with others I lead in the future, what should I continue to do? What should I do differently?

The first few times you try any of these techniques you may feel awkward, but our reflexive aversion to feelings of awkwardness is one of the forces that causes us to fail to mark endings in the first place. In my coaching practice and in my work with MBA students I regularly encourage people to increase their “comfort with discomfort” as a means of better managing difficult situations, and here I encourage you to persist and not allow feelings of awkwardness to dissuade you from acknowledging important endings. With a modest amount of effort and forethought, we can develop the same facility with saying goodbye deliberately that we have for other meaningful transitions in our lives.

Yes, You Can Have a Million-Dollar Business with No Employees

Census figures show that the number of one-person businesses in the U.S. with revenues between $1 million and $2.99 million rose 10% year-over-year in 2012 to more than 29,000 firms, Forbes reports. Most are professional, scientific, and technical-services companies, but retail and construction firms are well represented too. Still, such companies are rare: Firms with sales over $1 million make up far less than 1% of the nation’s 22.7 million nonemployer companies, for which the largest revenue category is $10,000 to $25,000.

Marketing Can No Longer Rely on the Funnel

One of the central concepts of marketing and sales is the funnel — through which companies are supposed to systematically move prospects from awareness through consideration to purchase.

But consumers are now more informed, connected, and empowered than ever. Does the funnel still work in a digital, social, mobile age?

We asked some of the leading marketers in the world — from companies like Google, Intuit, Sephora, SAP, Twitter, and Visa — to assess the relevance of the marketing funnel. What we found says as much about the future of business as it does about the future of marketing.

According to these marketers, the primary problem with the funnel is that the buying process is no longer linear. Prospects don’t just enter at the top of the funnel; instead, they come in at any stage. Furthermore, they often jump stages, stay in a stage indefinitely, or move back and forth between them.

For example, consider items that come recommended on an e-commerce site. With a click you can add them to your cart, moving straight from awareness through consideration to purchase in only a few seconds. The same holds true on items discovered in a Tweet, Facebook post, or Pinterest board.

In both B2B and B2C businesses, customers are doing their own research both online and with their colleagues and friends. Prospects are walking themselves through the funnel, then walking in the door ready to buy.

As an example, Julie Bornstein, CMO at Sephora, has seen social media change how people buy beauty products. Recommendations from friends have always been important, but now these recommendations spread “quicker, faster, and further” at every stage in the funnel. The decision on what to buy increasingly comes from advocates who share their experience in a way that pulls in new customers and informs their purchase decision. Sephora’s response has been to bring all the stages of the funnel together into a single place, creating its own online community where people can ask questions of experts and each other about brands, products, and techniques.

One popular alternative to the funnel is the Customer Decision Journey popularized by McKinsey. A key advantage of this model is that it’s circular, rather than linear. Prospects don’t come in the top and out the bottom, but move through an ongoing set of touchpoints before, during, and after a purchase.

The Customer Decision Journey is an improvement over the traditional funnel, but some marketers see it as incomplete. The problem is in the name itself. Brands may put the decision at the center of the journey, but customers don’t. Jonathan Becher, CMO at SAP, believes that for customers, “the pivot is the experience, not the purchase.” The Customer Decision Journey might be circular, but if the focus is still on the transaction, it is just a funnel eating its own tail.

One of the most critical weaknesses of the Customer Decision Journey is the connection between purchase and advocacy. Almost every marketer we spoke to described how social media has disconnected advocacy from purchase. “You no longer have to be a customer to be an advocate. The new social currency is sharing what’s cool in the moment,” says Joel Lunenfeld, VP of Global Brand Marketing at Twitter.

In today’s marketing landscape, people can experience a brand in many ways other than purchase and usage of a product. These include live events, content marketing, social media, and word-of-mouth. Consider all the members of the Nike+ running community who don’t own Nike products or the half million fans of Tesla’s Facebook page who don’t own a Tesla. Or consider companies where employees use their own devices or download their own software until IT purchases the enterprise version for the entire company. In today’s digital age, advocates aren’t necessarily customers. Marketers who think that advocacy comes after purchase are missing the new world of social influence.

Antonio Lucio, Chief Brand Officer at Visa, believes the solution is to shift the focus from the transaction to the relationship. After exploring the Customer Decision Journey, his team developed what they call a Customer Engagement Journey. In this model, transactions occur in the context of the relationship rather relationships in the context of the transaction.

As an example, consider a real world journey of a family’s trip from the U.S. to Mexico. Visa has mapped out the entire experience, from where the family gets ideas on where to go (TripAdvisor), to how they gather input from friends (Facebook), to how they pay for their cab (cash from an ATM) or hotel (credit card), to how they share photos of their trip with friends back home (Instagram). Only a few of these situations are opportunities for transactions, but they are all opportunities for relationship. “When you change from decision to engagement,” Antonio says, “you change the entire model.”

Market trends suggest the mismatch will only widen between customers’ actual experiences and the models of the funnel or Customer Decision Journey. One key trend is the integration of marketing into the product itself. The funnel presumes that marketing is separate from the product. But for digital products like games, entertainment, and software-as-a-service, the marketing is built right into the product. Examples include the iTunes store and Salesforce’s App Exchange.

Caroline Donahue, CMO at Intuit, oversees numerous web-based products for which “the product and the marketing become one thing.” The funnel changes because “with cross-sell and up-sell, you move from awareness to action instantaneously.” Instead of a Customer Decision Journey, her approach might best be described as a User Experience Journey into which opportunities for transactions are thoughtfully embedded.

Google shares a similar view, taking the fusion of product and marketing one step further. Arjan Dijk, the company’s Vice President for Global Small Business Marketing, believes products should be designed to market themselves. For Google, the question is not “how can we market this product?” but “which products deserve marketing?” Marketing isn’t about “pushing people’s thoughts and actions. It’s about amplification, helping what’s already happening grow faster.”

So where do we go from here? The funnel and Customer Decision Journey aren’t going away. They are useful models, and will continue to be helpful in certain contexts. But marketing today requires a new mental map to navigate a changing landscape. We need a model that informs marketers how to enable and empower, not just persuade and promote. There are a variety of alternatives including journey, orbit, relationship, and experience.

Whatever model you choose, what’s most important is that it addresses: first, the multi-dimensional nature of social influence; second, non-linear paths to purchase; third, the role of advocates who aren’t customers; and fourth, the shift to ongoing relationships beyond individual transactions.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers