Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1405

June 23, 2014

Strategic Humor: Caption Contest for the October 2014 Issue

Test your management wit in the TWO HBR Cartoon Caption Contests we’re running this month. The first contest, for our September issue, can be found here, and the second contest, for our October issue, is below. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

OCTOBER CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below. To be considered for either of this month’s contests, please submit your caption by August 3.

Cartoonist: Crowden Satz

You’re More Likely to Reject Hierarchies if You Feel Unattractive

Research participants who had been asked to write about an incident in which they felt physically attractive were about half as likely to donate their $50 compensation to the Occupy movement as people who had been primed to think of themselves as unattractive, say Peter Belmi and Margaret Neale of Stanford. When people believe they’re attractive, they see themselves as belonging to a higher social class, a perception that results in their taking a more-favorable view of inequality, the researchers say. People who feel unattractive, by contrast, are more likely to reject inequality and social hierarchies.

Morning People Are Less Ethical at Night

Employees face many temptations to behave unethically at work. Resisting those temptations requires energy and effort. But the energy that is essential to exert self-control waxes and wanes. And when that energy is low, people are more likely to behave unethically. This opens up the possibility that even within the same day, a given person could be ethical at one point in time and unethical at another point in time.

Over the past few years, management and psychology research has uncovered something interesting: both energy and ethics vary over time. In contrast to the assumption that good people typically do good things, and bad people do bad things, there is mounting evidence that good people can be unethical and bad people can be ethical, depending on the pressures of the moment. For example, people who didn’t sleep well the previous night can often act unethically, even if they aren’t unethical people.

Our research started from this idea. Drawing from recent research indicating that people can become more unethical as the day wears on, we asked whether this plays out the same way for people who show different patterns of energy during the course of a day. Fatigue researchers have discovered that alertness and energy follow a predictable daily cycle that is aligned with the circadian process. However, different people may be shifted in their circadian rhythms. Some people are “larks” or “morning people” in that their circadian rhythm is shifted earlier in the day. They are most easily detected by their natural tendency to wake early in the morning. Others are “owls” or “evening people” and they are shifted in the opposite direction. Larks tend to get up early, and owls tend to stay up late.

Building from this research, we predicted that larks and owls would follow different patterns of ethical and unethical behavior over the course of a day. Because their energy levels should follow different patterns, and this energy is crucial for resisting temptation, we expected larks to be more unethical late at night than early in the morning, and owls to be more unethical early in the morning than late at night. To test this prediction, we conducted two laboratory studies.

In our first study, we focused only on behavior in the morning. We brought research participants into a laboratory, and gave them a simple matrix task in which we paid them additional money for each additional matrix that they said they solved. Participants believed that their work was anonymous, and could thus over-report to earn more money. But we were able to go back and determine how many they actually solved. In other words, we could determine who cheated by over-reporting the number of solved matrices. Consistent with our prediction, since these were morning sessions: night owls were more likely to cheat than larks.

In our second study, we tested the full prediction—that unethical behavior would depend on both circadian rhythms and the time of day. We randomly assigned a new set of research participants to a laboratory session either early in the morning (7-8:30am) or late at night (midnight-1:30am). Participants undertook a die rolling task previously established as a test for unethical behavior. In this task, they anonymously rolled a die and reported the number back to us, and we paid paying them based on the number they reported (higher amounts for higher rolls).

Although we didn’t know what numbers participants actually rolled, we did know that everyone should report an average of 3.5. So any systematic differences across conditions (morning people in the morning vs. evening people in the morning, for example), would indicate cheating. Consistent with our prediction, an interesting and statistically significant pattern emerged. Larks in the night session reported getting higher rolls (M=4.55) than larks in the morning sessions (M=3.86), and owls in the morning session reported higher rolls (M=4.23) than owls in the night sessions (3.80). This evidence is consistent with the idea that larks will be more unethical at night than in the morning, and that owls will be more unethical in the morning than at night. A more detailed description will be provided later this year in our forthcoming article in the journal Psychological Science.

The important organizational takeaway from these findings is that individual may be more likely to act unethically when they are “mismatched” –that is, making a decision at the wrong time of day for their own chronotype. Managers should try to learn the chronotype (lark, owl, or in between) of their subordinates and make sure to respect it when deciding how to structure their work. Managers who ask a lark to make ethics-testing decisions at night, or an owl to make such decisions in the morning, run the risk of encouraging rather than discouraging unethical behavior.

Similarly, people who control their own work schedules should structure their work with their chronotype in mind. Many of us are tempted to squeeze in that extra hour of work. If we’re a morning person squeezing it in at night, though, we create a situation in which resisting temptation may be harder than ever. Larks who schedule extra hours for themselves early in the morning face the same issue.

June 20, 2014

Instinct Can Beat Analytical Thinking

Researchers have confronted us in recent years with example after example of how we humans get things wrong when it comes to making decisions. We misunderstand probability, we’re myopic, we pay attention to the wrong things, and we just generally mess up. This popular triumph of the “heuristics and biases” literature pioneered by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky has made us aware of flaws that economics long glossed over, and led to interesting innovations in retirement planning and government policy.

It is not, however, the only lens through which to view decision-making. Psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer has spent his career focusing on the ways in which we get things right, or could at least learn to. In Gigerenzer’s view, using heuristics, rules of thumb, and other shortcuts often leads to better decisions than the models of “rational” decision-making developed by mathematicians and statisticians. At times this belief has led the managing director of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin into pretty fierce debates with his intellectual opponents. It has also led to a growing body of fascinating research, and a growing library of books for lay readers, the latest of which, Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions, is just out.

During a visit to HBR’s New York office, Gigerenzer discussed his work for an Ideacast podcast, which you can listen to here:

We then continued talking well past the Ideacast time limit. What follows is a much-edited rendition of the full conversation.

HBR: Most of us are used to hearing about how bad we are at making decisions under conditions of uncertainty, and how our intuitions often lead us astray. But that’s not entirely the direction your research has gone in, correct?

Gerd Gigerenzer: I always wonder why people want to hear how bad their own decisions are, or at least, how dumb everyone else is. That’s not my direction. I’m interested to help people to make better decisions, not to state that they have these cognitive illusions and are basically hopeless when it comes to risk.

But a lot of your research over the years has shown people making mistakes.

Just imagine, a few centuries ago, who would have thought that everyone will be able to read and write? Now, today, we need risk literacy. I believe if we teach young people, children, the mathematics of uncertainty, statistical thinking, instead of only the mathematics of certainty – trigonometry, geometry, all beautiful things that most of us never need – then we can have a new society which is more able to deal with risk and uncertainty.

By teaching people how to deal with uncertainty, do you mean taking statistics class, studying decision theory?

If you’re in the world where you can calculate the risk, then statistical thinking is enough, and logic. If you go in a casino and play roulette, you can calculate how you will lose in the long run. But most of our problems are about uncertainty. So, for instance, in the course of the financial crisis, it was said that banks play in the casino. If only that would be true — then they could calculate the risks. But they play in the real world of uncertainty, where we do not know all the alternatives or the consequences, and the risks are very hard to estimate because everything is dynamic, there are domino effects, surprises happen, all kinds of things happen.

Risk modeling in the banks grew out of probability theory.

Right, and that’s the reason why these models fail. We need statistical thinking for a world where we can calculate the risk, but in a world of uncertainty, we need more. We need rules of thumb called heuristics, and good intuitions. That distinction is not made in most of economics and most of the other cognitive sciences, and people believe that they can model or reduce all uncertainty to risk.

You tell a story that I guess is borrowed from Nassim Taleb , about a turkey. What’s the problem with the way that turkey approached risk management?

Assume you are a turkey and it’s the first day of your life. A man comes in and you believe, “He kills me.” But he feeds you. Next day, he comes again and you fear, “He kills me,” but he feeds you. Third day, the same thing. By any standard model, the probability that he will feed you and not kill you increases day by day, and on day 100, it is higher than any before. And it’s the day before Thanksgiving, and you are dead meat. So the turkey confused the world of uncertainty with one of calculated risk. And the turkey illusion is probably not so often in turkeys, but mostly in people.

What kind of rule of thumb would help a person, or a turkey, in that sort of situation?

Let’s use people for that. For instance, the value at risk and other standard models that rating agencies used before the crisis in 2008 — the same thing happened there. The confidence increased year by year, and shortly before the crisis, it was highest. These types of models cannot predict any crisis, and have missed every one. They work when the world is stable. They’re like if you have an airbag in your car that works all the time except when you have an accident.

So we need to go away from probability theory and investigate smart heuristics. I have a project with the Bank of England called simple heuristics for a safer world of finance. We study what kind of simple heuristics could make the world safer. When Mervyn King was still the governor, I asked him which simple rules could help. Mervyn said start with no leverage ratio above 10 to one. Most banks don’t like this idea, for obvious reasons. They can do their own value-at-risk calculations with internal models and there is no way for the central banks to check that. But these kinds of simple rules are not as easy to game. There are not so many parameters to estimate.

Here’s a general idea: In a big bank that needs to estimate maybe thousands of parameters to calculate its value-at-risk, the error introduced by these estimates is so big that you should make it simple. If you are in a small bank that doesn’t do big investments, you are in a much safer and more stable mode. And here, the complex calculations may actually pay. So, in general, if you are in an uncertain world, make it simple. If you are in a world that’s highly predictable, make it complex.

What about the role of intuition and gut feelings in all of this? Clearly, in business, that’s a big issue.

Gut feelings are tools for an uncertain world. They’re not caprice. They are not a sixth sense or God’s voice. They are based on lots of experience, an unconscious form of intelligence.

I’ve worked with large companies and asked decision makers how often they base an important professional decision on that gut feeling. In the companies I’ve worked with, which are large international companies, about 50% of all decisions are at the end a gut decision.

But the same managers would never admit this in public. There’s fear of being made responsible if something goes wrong, so they have developed a few strategies to deal with this fear. One is to find reasons after the fact. A top manager may have a gut feeling, but then he asks an employee to find facts the next two weeks, and thereafter the decision is presented as a fact-based, big-data-based decision. That’s a waste of time, intelligence, and money. The more expensive version is to hire a consulting company, which will provide a 200-page document to justify the gut feeling. And then there is the most expensive version, namely defensive decision making. Here, a manager feels he should go with option A, but if something goes wrong, he can’t explain it, so that’s not good. So he recommends option B, something of a secondary or third-class choice. Defensive decision-making hurts the company and protects the decision maker. In the studies I’ve done with large companies, it happens in about a third to half of all important decisions. You can imagine how much these companies lose.

But there is a move in business towards using data more intelligently. There’s exploding amounts of it in certain industries, and definitely in the pages of HBR, it’s all about Gee, how do I automate more of these decisions?

That’s a good strategy if you have a business in a very stable world. Big data has a long tradition in astronomy. For thousands of years, people have collected amazing data, and the heavenly bodies up there are fairly stable, relative to our short time of lives. But if you deal with an uncertain world, big data will provide an illusion of certainty. For instance, in Risk Savvy I’ve analyzed the predictions of the top investment banks worldwide on exchange rates. If you look at that, then you know that big data fails. In an uncertain world you need something else. Good intuitions, smart heuristics. But most of economics is not yet prepared to admit that there would be another tool besides expected utility maximization.

You tell the story in your book of Harry Markowitz , who introduced expected utility maximization to the world of investing with modern portfolio theory. How does he actually choose his investments?

When Harry Markowitz made his own investments for the time after his retirement, he relied on a simple heuristic. A quite intuitive one, which is invest your money equally. If you have two options, 50-50; three, a third, a third, a third; and so on. It’s called “one over N.” N is the number of options. We and others have studied how good one over N is. In most of the studies, one over N outperforms optimizing Markowitz portfolios.

Can we identify the world in which a simple heuristic, one over N, is better than the entire optimization calculation? That’s what Reinhard Selten and I call the study of the ecological rationality of a heuristic. If the world is highly predictable, you have lots of data and only a few parameters to estimate, then do your complex models. But if the world is highly unpredictable and unstable, as in the stock market, you have many parameters to estimate and relatively little data. Then make it simple.

To use the taxonomy popularized in the last couple of years by Daniel Kahneman, it’s not about putting system two in charge, and keeping system one under control. It’s about figuring out which situations are best for each.

I have my own opinion about system one and system two, and if you want me to share …

Well, I know you and Kahneman have been debating these things for decades, so sure.

What is system one and system two? It’s a list of dichotomies. Heuristic versus calculated rationality, unconscious versus conscious, error-prone versus always right, and so on. Usually, science starts with these vague dichotomies and works out a precise model. This is the only case I know where one progresses in the other direction. We have had, and still have, precise models of heuristics, like one over N. And at the same time, we have precise models for so-called rational decision making, which are quite different: Bayesian, Neyman-Pearson, and so on. What the system one, system two story does, it lumps all of these things into two black boxes, and it’s happy just saying it’s system one, it’s system two. It can predict nothing. It can explain after the fact almost everything. I do not consider this progress.

The alignment of heuristic and unconscious is not true. Every heuristic can be used consciously or unconsciously. The alignment between heuristic and error-prone is also not true. So, what we need is to go back to precise models and ask ourselves, when is one over N a good idea, and when not? System one, system two doesn’t even ask this. It assumes that heuristics are always bad, or always second best.

It seems like in leadership in business and elsewhere, you really are stuck or blessed with heuristics, because the whole idea is you’re pushing into unknown territory. For a leader, what are some of the key heuristics you’ve found over the years that seem to work?

There are heuristics that we can simulate and mathematically treat. But others are more like verbal recipes. The more uncertain the world is, the more you need to go into verbal recipes.

There’s an entire class of heuristics that I call one-good-reason decision-making. Assume you have a large company with a customer base of 100,000, and you want to not target those customers who will never buy from you. So, how to predict which customers will buy, and which will not? According to standard marketing theory, it’s a complex problem, so you need a complex solution — for instance, the Pareto negative binomial distribution model, which has four parameters you estimate and gives you the probability for each customer that he or she will make future purchases. The other vision is it’s a complex problem in a world of uncertainty. Therefore, you need to find a simple solution because you will get too much error by making all these estimates.

The hiatus heuristic is an example: if a customer has not bought for at least nine months, classify as inactive; otherwise, active. Now, you might say, relying on one good reason can never be better than relying on this reason and many others, and doing impressive mathematical computation. But that’s a big error in a world of uncertainty. Studies have shown that for, instance, at an airline, the simple heuristic predicted future customer behavior better than the complex Pareto model. The same for an apparel business.

Less was more.

Yeah, less is more. A number of studies have shown, for instance, that in language learning what works is a limited memory and simple sentences. Parents do this intuitively. It’s called baby talk. And that works. And children learn. And then, the sentences get a little bit more complex, and the memory gets extended and this is the way to make a good language understanding.

The problem of the heuristics and biases people, including much of behavioral economics, is they keep the standard models normative, and think whenever someone does something different, it must be a sign of cognitive limitations. That’s a big error. Because in a world of uncertainty, these models are not normative. I mean, everyone should be able to understand that.

I hope that at some point, the economists turn around and realize that their models are good for one class of situations, but not for another. And also, that psychologists and also economists realize that there’s a mathematical study of heuristics. That heuristics are not just words like availability or representative that explain everything post-hoc, but can predict things. One over N, recognition heuristic, one-good-reason can predict very well, and can be shown to be wrong in certain situations.

The recognition heuristic is a classic one, where there’s been lots of stock market research done by people like Terry Odean at Berkeley about how people made bad decisions in investing because of the recognition heuristic. But you’ve done studies that found Americans were better than Germans at picking which of various pairs of German cities had the higher population, and Germans were better than Americans on the American cities, because the foreigners simply picked the cities they recognized.

The fun thing is that the entire idea that a simple heuristic could do well arises so much resistance. There were two Germanpsychologists who said okay, we believe that people rely on this heuristic, but it can’t be good. And they were arguing that because the cities are a stable world, it may work there. But they selected a world where they thought that Germans were really biased. It’s the prediction of all Wimbledon tennis matches in gentlemen’s singles.

They were arguing, first, it’s a highly dynamic environment. The winner of last time is no longer the winner this time. Second, we use Germans’ predictions and German players did not do very well. This was the time after Becker. They had three gold standards, which was the two ATP rankings — one is a moving year, the other is calendar year — and the Wimbledon seeding. Then, they needed people who are semi-ignorant, and the ideal group is those who has heard of half of the players and not heard of the other half. They found German amateur players in Berlin, who had not even heard of half of these guys. So they made a recognition ranking.

What was the result? The ATP ranking number one got 66% correct. The other ATP ranking got 68%, the Wimbledon seedings did 69%. And the recognition heuristic correctly predicted 72% of the match results. That was not what they wanted to show. That was repeated two years later, with basically the same result.

Everything You Didn’t Know You Wanted to Know About the Pallet Industry

Taking a cue from a recent Cabinet magazine story, NPR's Planet Money takes you into the weird and wonderful world of pallets. Yes, those big, flat structures that hold products for transport. The story goes like this: For decades, the standard in the pallet industry was stringer pallets, which forklifts could pick up from two of the four sides. But then an Australian company came up with a new version that could be lifted from any side. Great, right? Not so fast. This updated model, made by a company called CHEP, was about twice as expensive to buy. So CHEP did something kind of genius: It rented out the containers and then picked them up once a shipment was delivered. That's why they're painted bright blue, and the company even holds contests for employees who can spot and bring home pallets that were somehow left in the wild.

While this is all well and good for CHEP and companies like Costco that use its pallets, the Cabinet story also reveals a bit of an ugly side to the business. Traditionally, pallets didn't necessarily "belong" to anyone, so people could make money by collecting unused pallets, refurbishing them, and selling them for profit. You can imagine what happened when people started doing this with CHEP's new blue inventions.

Hachette JobAmazon vs. Hachette: The Battle for the Future of PublishingKnowledge@Wharton

Amazon: Gotta love it. Or hate it, depending on where you stand on the ebook-discount fight being waged on your laptop and tablet. Knowledge@Wharton gets a nice little debate going in this explainer about Amazon’s tactics to force publisher Hachette to get with the program. The personae include Wharton management professor Daniel Raff, who points out the dangers of Amazon’s growing control over cultural products, and venture capitalist David Pakman, who takes the kind of position a venture capitalist would, namely that publishers need to wake up to the realities of the digital world. “Digital markets produce much lower profit per item,” Pakman lectures us. Publishers must therefore rebuild their cost structure by doing such things as “moving to a less fancy office and lowering [managers’] salaries.” Photos of David Pakman’s desk and an estimate of his salary were unavailable to the Shortlist at press time. —Andy O’Connell

Maybe NotDoes Innovation Always Lead to Gentrification? Pacific Standard

Every struggling city hopes to grow an “innovation district” that will populate its old brick warehouses with teams of brainy entrepreneurs. But when innovation of this kind comes to cities, the price of everything goes up, and the poor and middle class are displaced, often without benefiting economically. “Innovators don’t create affordable housing,” Kyle Chayka writes in Pacific Standard. “They have little incentive to build a more equitable community.” Instead, they merely reproduce their own kind. He argues that cities should take a holistic view of innovation zones, setting them up so as to ensure sustainable, organic growth that’s woven into the pre-existing urban fabric, rather than simply plopping them “onto an empty-looking post-industrial neighborhood.” Educational institutions should be guaranteed space in these zones at low rents. That way, cities can have a shot at energizing not just the latte class but the entire population. —Andy O’Connell

A Chilling EffectGM Recalls: How General Motors Silenced a Whistle-BlowerBusinessweek

We've been hearing a lot about GM's efforts to encourage employees to speak up these days. But as Businessweek points out, the 325-page Valukas report provides clues about how deep the problems were and what the company’s culture really felt like: "On page 93, a GM inspector named Steven Oakley is quoted telling investigators that he was too afraid to insist on safety concerns with the Cobalt after seeing his predecessor 'pushed out of the job for doing just that.'" That predecessor is third-generation GM employee Courtland Kelley, who was ignored when he regularly pointed out safety problems. Management moved him around the company to the point where, according to a former colleague, "He still has a job — but he doesn't have a career."

Beyond StereotypesA Portrait of Europe's White Working ClassFinancial Times

What happens when an entire population is, as the FT's Simon Kuper reports, "hit by deindustrialisation, economic crisis and the crumbling of the welfare state"? And, while we're at it, what happens when it's "typically depicted either as a joke or a threat"? Kuper's deeply reported piece, stemming from a recent report by the Open Society Foundations, examines Manchester's Higher Blackley neighborhood, a place where people want to work but can't find steady jobs, and from which they don't want to move because of their strong community ties. In fact, everyone interviewed by the OSF wanted to work. But among the problems is one that should be instantly recognizable: "Younger mothers, in particular, wanted 'local, flexible work that fitted in with children’s hours.'"

"Still," writes Kuper, in reference to commonly held stereotypes, "blaming poverty on bad behavior is appealing, because it implies that all the government has to do is fix people’s behavior. There’s no need to raise the minimum wage, provide affordable childcare or improve mental-health services."

BONUS BITSA Debate About Robots (and Ebooks for All!)

This is Probably a Good Time to Say That I Don’t Believe Robots Will Eat All the Jobs… (Marc Andreessen)

Dear Marc Andreessen (Alex Payne)

Building Digital Libraries in Ghana with Worldreader (Medium)

Write Umbrella Agreements to Foster Innovation and Avoid Regret

You’re an executive of a clothing retailer and your marketing team detects a new trend that you’re well-positioned to feed. But your agreements with your suppliers prevent you from moving quickly.

Or you’re an auto-industry executive and you’re excited by a new technology that you could easily build into your latest model—but contracts with suppliers make such an innovation an impossibility this year, and maybe even next year.

In industry after industry, companies set themselves up for regrets and, sometimes, money-wasting conflicts when they form relationships with other businesses such as suppliers and dealers. They get locked into detailed agreements that turn out to be poorly aligned with their aspirations and that provide no room for innovation when markets change.

But there’s a solution: More and more multinational corporations are experimenting with creating meta-agreements that spell out their aspirations. In studying these business agreements over the past decade, I’ve found that they represent a radical advance from business as usual. They help address the problems of traditional business relationships, allowing the parties to understand one another’s values and restructure their interactions in real time. In so doing, they provide room for joint development of innovative ideas in response to new circumstances and opportunities.

There’s a lot of variety in how these umbrella agreements are structured and implemented. Unfortunately, many of them are inadequate, either because they contain vague, unwieldy language or unenforceable rules, or because they’re still too inflexible. In order to be effective, umbrella agreements must articulate companies’ values and their expectations for other firms’ behavior in language that is binding and enforceable, while providing mechanisms for revisiting aims and tasks.

Consider the failed merger of Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank, which would have formed the largest bank in the world. The parties had an umbrella agreement for a merger of equals, but it left too much unsaid—it failed to specify how the deal should work in practice. One month after announcing the agreement, Deutsche Bank clarified its expectation that Dresdner’s division of investment banking, DKB, would be sold, either in parts or in its entirety. Dresdner was blindsided—its understanding of the umbrella agreement with Deutsche Bank had been that investment banking was an essential part of the overall deal. Deutsche Bank accused Dresdner of inflexibility. The agreement was called off.

In order to structure a business relationship to foster innovation and avoid regret, business partners must follow several specific steps. They must:

commit to working jointly; for example, parties must commit to the scope and boundaries of their agreement, the duration, and the resources that they are willing to bring into their joint action;

understand and articulate their own corporate values (for example, a company might be strongly focused on avoiding excessive risk) and explicitly include those values in the umbrella agreement;

specify how and when, on a regular basis, the partnership’s business performance will be reviewed (for example, monthly, quarterly, or annually) and what kinds of flexibility will be built into it;

spell out who interacts with whom across the companies—for example, the national account director will interact with the sourcing director, while the business manager interacts with the category manager and sales reps interact with store managers; and

establish notification requirements and clear means, such as task forces, for resolving issues around prices, volumes, performance monitoring and other detailed matters.

Effective umbrella agreements are in use by such consumer-goods retailers such as Walmart, Tesco, and Rewe, which have tended to structure their agreements with companies such as Procter & Gamble, Unilever, and Kellogg so as to encourage the manufacturers to maintain flexibility and embrace opportunities for innovation.

Each year between September and December, grocery retailers and manufacturers of laundry and cleaning products enter into annual negotiations to structure frameworks that spell out their aspirations and values as well as specific rules with regard to how the counterparts wish to work together. Retailers and manufacturers specify how they intend to create value by addressing consumer needs and how value will be distributed between them, while leaving details such as prices and volumes to be agreed upon later.

Retailers’ agreements with manufacturers might include clauses like these:

Both parties have the right obtain competitive offers at any time.

The agreement can be renegotiated annually if one party wishes.

The manufacturer and retailer will share industry knowledge with each other.

Mutual notification is needed for all future capital investment and R&D.

Subcontracting is permissible, but only with the other party’s consent.

The parties agree to implement continuous stock replenishment based on electronic data interchange.

Wholesale prices are determined unilaterally by the manufacturer, and retail prices are determined unilaterally by the retailer.

Payment must be made in 30 days and delivery costs are paid by the supplier.

Invalidation of one or more clauses will not have any effect on the umbrella agreement as a whole (unless the clause is of major importance).

Every complex, multilayered, continuing business relationship that’s subject to a changing environment would benefit from a well-crafted umbrella agreement—one that’s constructive, positive, and forward-looking and allows the counterparts to embrace new opportunities.

Focus On: Negotiating

Negotiating Is Not the Same as Haggling

Negotiate from the Inside Out

To Negotiate Effectively, First Shake Hands

The Simplest Way to Build Trust

CMOs and CEOs Can Work Better Together

When Deborah DiSanzo took over as CEO of Philips Healthcare in May 2012, she knew that engineering would continue to drive innovation. But she also realized that the company needed to develop greater marketing muscle to drive a commercial transformation. As she put it, “Our markets are going through dynamic change. Who should lead our transformation? It must be marketing. Marketers need to know where their markets are going and where their customers are going, and then lead the rest of the organization.”

DiSanzo started by consolidating an astounding 600 different marketing titles into eight consistent job areas with specific and clear areas of responsibility. She also took the unusual step of installing three CMOs who could help provide detailed insights into three of the main business groups of the company. And she put marketing in charge of an organization-wide growth program.

The changes in healthcare – consolidation, restructuring, regulation, spending pressures – that are necessitating a transformation at Philips Healthcare are a subset of a series of powerful forces in the business world that have catapulted marketing from an often-isolated support function to a critical capability for driving above-average growth. Marketing has become increasingly essential for discovering meaningful insights, designing strategies and offers based on them, and delivering them to the marketplace. We have seen these forces at work in many different industries around the world, requiring a decidedly closer working relationship between the CEO and CMO.

The CMOs will need to be much more attuned to the business objectives and strategies of the company in general and the CEO in particular, while the CEO must become more immersed in the customer perspective. In our experience, there are specific steps CEOs and CMOs can take to develop a working relationship that is dynamic and useful.

Here are our recommendations for the CEO:

Give the CMO a seat at the executive table. The CEO can raise the CMO’s profile and communicate the heightened importance of marketing in a number of both formal and (often just as important) informal ways. Giving the CMO a clear role in the strategic planning process is a good start. It’s a practical way not only to inject a customer perspective into the core planning activities, but it also provides the CMO with the big-picture business perspective. The CEO can also make it a point to elicit marketing’s point of view on customer issues during strategy discussions, and carve out time for one-on-one meetings. “We are always on the agenda of the executive team and are a significant part of the leadership meetings,” says Bert van Meurs, CMO of Philips Healthcare Imaging Systems.

Tariq Shaukat, CMO for Caesars, agrees. “One thing that [CEO] Gary Loveman has done is make it clear to me and to others that he views marketing as a core driver of the business. And as such, marketing is involved with the business reviews, strategy sessions, and financial reviews too.”

Informal practices can be even more helpful. At Essent, the Dutch energy company, CEO Erwin van Laethem provided practical guidance to his CMO. “My CEO could read the company like a book,” says Dorkas Koenen, Essent CMO. “He’d warn me at the right time and place, and say, ‘Hey Dorkas, look out. This will probably happen if you don’t do that.’ That was very helpful.”

These actions alone, however, aren’t enough. While marketing budgets have been steadily rising as a percentage of firm budgets since 2011, many CMOs still lack real authority over decisions that most affect the customer, since most are delivered through touch points not owned by marketing. The CEO can help by putting the CMO in charge of important initiatives and granting veto power on certain decisions that impact customers. For example, at Essent, the CEO changed the reporting structures so that all people in the company with a marketing role reported to the CMO, which in one fell swoop provided the CMO with a significant set of resources. In yet another example, Caesars took the step of centralizing marketing and sales budgets, as well as decision rights, under the CMO.

Make the CMO the “bonding agent” that connects the organization. When making a purchase decision, customers use an average of six different channels, which are often managed by different parts of the organization. That series of interactions – or “customer journeys” – highlights a crucial issue in today’s business world: brands need to work across multiple functions to deliver a coordinated and consistent experience. Companies that excel in delivering on those customer journeys can increase revenue growth 10 – 15 percent and lower costs to serve 15 – 20 percent.

The CEO must establish a method that lets the CMO work effectively with other executives.Phillips Healthcare’s DiSanzo addressed this issue by developing a process that takes a product from concept to the marketplace. That process incorporates operations, customer service, R&D, clinical specialists, sales, supply chain operators, and service teams. Marketing is the “glue” that integrates those elements across the entire process by providing consistent oversight, expertise, and guidance.

Become an active marketer. “So much of the CEO’s job is actually marketing the company,” says Shaukat of Caesars. “They’re one of the primary people defining the company to consumers, investors and the business community.”

Caesars CEO Loveman participated in a two-day quarterly marketing council session, which brought together all the senior marketers in the company. “It is critical for the CEO to be a part of the creation of our marketing strategies and not just be a recipient of them,” says Shaukat. “He has to invest the time and energy not just reading documents but really problem solving.” Loveman worked with marketers to break through issues, brainstorm solutions, and provide thoughtful feedback on various marketing initiatives.

At Essent, van Laethem took a personal role in finding marketing talent and in many cases interviewed people for senior roles. At Philips Healthcare, DiSanzo meets with her CMOs every two weeks.

While the onus is on the CEO to create the environment and structure that puts the CMO in the best position to succeed, we have found that CMOs can do three things specifically to support his/her CEO and drive above-market growth.

Develop—and stick to—a marketing blueprint. Most companies have a marketing plan; surprisingly few have a plan for marketing. Done well, however, a marketing blueprint details how marketing will deliver against the company’s business goals. It specifies what gets done, by whom, in support of what, over what period of time, and makes explicit connections among marketing activities, target goals, and corporate business goals. The marketing plan also has explicit links to business and operating plans within the organization so that, for example, manufacturing is prepared to support the volume increase that marketing is planning to spur, or sales forces are staffed and trained to handle new product launches.

When properly formulated, the plan not only tracks progress on near- and medium-term goals but also tracks long-term corporate health. Using brand equity trackers and marketing mix models, for example, the CMO can deliver reasonable estimates of long-term brand effects. This insight is critical in helping the CEO understand corporate health over the longer-term. For new CMOs, we recommend putting this blueprint in place within 90 days of taking office.

Connect the CEO to the customer. The CMO needs to provide a deep and detailed understanding of the customer to the entire organization based on rigorous analytics. Key performance indicators (KPIs) that integrate customer insights relevant to growth need to be incorporated into the executive dashboard. In particular, we’ve found that focusing on the consumer decision journey (http://mckinseyonmarketingandsales.com/winning-the-consumer-decision-journey) allows CMOs to develop a clear picture of behaviors, moments of influence, and battlegrounds. That level of insight is invaluable to the organization and particularly to the CEO.

Some CMOs take this notion of connecting the CEO to the customer a step further by making it a point, for example, to include the CEO in at least one customer visit per month—whether at a retail store, or listening in on a call center operation. Ford decided to create a mechanism that lets the head of social media connect directly to Ford’s CEO, Alan Mulally. One day, this Tweet caught the team’s attention: “I’m a Volkswagen/Audi guy and I’m driving this new Edge Sport, and I think it’s pretty cool.” The social media head asked the Tweeter for his phone number, and he was still taking the test drive when he received a call from the CEO himself, thanking him for considering Ford’s Edge Sport.

Expand marketing’s influence across the organization. While the CEO can establish the cross-functional mechanisms across the organization that set the CMO up for success, it’s up to the CMO to make them work. Since the CMO often does not have authority over relevant functions (e.g. sales, operations, IT), it requires being able to work well with other leaders to influence outcomes. That can sometimes be an uphill battle.

Whether deserved or not, marketing often has a reputation as something of a luxury, with an indeterminate “value add.” This is largely because marketing’s contribution to a company’s success is not well understood. “Marketing too often is a black box,” says Essent CMO Koenen. “You should bring all the leaders in and make them owner of a marketing program. It was particularly important to work with Patrick Lammers, my CCO (Chief Customer Officer), to turn around the organization. I think that’s probably the most important thing that we’ve done here at Essent.”

The marketing team at Starwood Hotels & Resorts Group also offers a good example of cross-functional cooperation in action. The group set out to design the ideal customer experience across its brands (from the St. Regis to Sheraton Four Points) and touch points, from the concierge stationed in the hotel lobby to social media. By coordinating the brand experience across functions, assigning which departments would control the different touch points, customizing content delivery across the company website and mailings, and most importantly holding themselves accountable for the results, Starwood was able to substantially increase share of wallet from their customers.

The C-suite can seem like an unstable place – just look at the high CEO and CMO turnover rates, and the recent proliferation of new roles such as Chief Digital Officer and Chief Customer Officer. But the demands of the business remain unchanged: delivering above-market growth. While roles will need to adapt to the needs of each business, the CEO-CMO partnership should form the foundation of any company’s successful growth strategy.

Special thanks to Tim McGuire, Tim Koller , and Liz Hilton Segal.

Signs You’re Being Passive-Aggressive

When was the last time you did any of the following at work?

You didn’t share your honest view on a topic, even when asked.

You got upset with someone, but didn’t let them know why.

You procrastinated on completing a deliverable primarily because you just didn’t see the value in it.

You praised someone in public, but criticized them in private.

You responded to an exchange with, “Whatever you want is fine. Just tell me what you want me to do,” when in actuality, it wasn’t fine with you.

Whether intentional or not, these are all signs you’re being passive-aggressive. Whenever there is a disconnect between what you say (passive) and what you do (aggressive), you fall into that camp. And while it’s easy to recognize a passive aggressive co-worker — the colleague who is agreeable to your face but badmouths the idea behind your back or the sarcastic direct report whose constant retort is “but it was just a joke” — recognizing one’s own passive-aggressive behaviors at work can be quite difficult.

Take Chris, for example, a senior marketing executive that I coached. When we discussed the 360 feedback he’d received as part of a leadership development program, he was shocked at what his colleagues wrote about him:

“You never quite know where Chris stands on an issue. He’ll agree to one thing in a meeting but then do something completely different in the follow through. That can make it hard to trust him.”

“While Chris is a really nice guy, I wonder if he’s really honest with his views. He’ll say he’s fine with some thing but you can just tell he’s not and he’s saying that just so we can move on.”

“Chris makes backhanded comments about the quality of someone’s work or idea without directly addressing the issue with the person. It comes off as snarky. It’s not what you’d expect of a leader.”

While Chris admitted that there was some truth to what was described, he bristled at the thought of being perceived as passive-aggressive. Yet that’s exactly what he was.

Over time, passive-aggressive behavior is a slippery slope that breeds mistrust and chips away at your credibility. Being known as passive-aggressive will not serve you well in your career. Fortunately, it’s possible to change your behavior. Though it requires a commitment to self-development and a willingness to get out of your comfort zone.

Here are five strategies to consider:

1. Recognize the behavior. It’s important that you recognize which circumstances or situations drive you to be passive-aggressive. Knowing what they are helps you consciously explore other ways to respond. Start by thinking about the circumstances that bring out these behaviors: Who was involved? How did the situation unfold? How did you react? What happened? Do you see a pattern? Chris recognized that when he felt like his contributions were not valued or like he wasn’t being heard, he resorted to a passive-aggressive stance. This particularly true in leadership team meetings where Chris felt like he had to defend marketing’s role, value, and resources to the rest of the organization. He had a hard time understanding why he was always being tested.

2. Identify the cause. There is likely an underlying cause for your passive-aggressiveness — it can be a fear of failure (a desire for perfection), a fear of rejection (a desire to be liked), or a fear of conflict (a desire for harmony). It’s critical to understand the root of the issue so that you can address it head on and determine whether your fear is warranted. For Chris, the root cause was a fear of conflict and the belief that if others valued him, they wouldn’t push and question him and his group. In effect, Chris equated any sign of conflict with not being valued. Yet, nothing could be further from the truth. Others questioned marketing because they saw it as a critical part of the business and wanted to ensure its success. When Chris realized how his beliefs were driving his passive-aggressive behavior, he saw how important it was to change his default response.

3. Be honest with yourself. Once you understand the underlying reasons for your behavior, you need to be honest with yourself about what you really want. Continuing to veil or deny your feelings will only perpetuate the passive-aggressive response. What is it that you truly think? What is it that you really want to say? What outcome are you hoping for? Then think about how to express that desire in a direct, but respectful, way.

4. Embrace conflict. A large part of letting go of passive-aggressive behavior is accepting that conflict happens. Conflict at work (or anywhere) is not necessarily a bad thing if you make an effort to move through it productively. Seek mutual understanding (not to be mistaken with mutual agreement) of each other’s positions and recognize that even if you don’t agree with someone, it typically does not mean that the relationship is in jeopardy. By accepting that engaging in conflict enhanced what his division had to offer rather than derailing its work, Chris more readily took part in those interactions. Instead of shutting down the exchanges by offering a fake agreement or withholding critical feedback, he respectively disagreed and asked questions to better understand his colleagues’ perspectives.

5. Get input. Working on any behavioral change is hard. It’s easy to be overly critical of your own efforts or simply disappointed that you’re not seeing enough progress. For that reason, it’s important to check in with others on how you’re doing. Share what you’re working on with a few folks that you trust. Periodically, ask them how you’re doing. Do they get the sense that you’re just talking the talk, or actually walking the walk? Chris’s road was not an easy one and every now and then he defaulted back to his passive-aggressive response. But over time, those occasions became more and more rare as Chris focused on being direct and clear in what he wanted to communicate. Some of his confidantes did a good job holding him accountable, even going as far as kicking him under the table during team meetings if he started showing the passive-aggressive behavior that he’d worked so hard to shed.

Managing your own passive aggressive behaviors is about getting rid of the incongruity between your internal dialogue — what you think — and your external actions — what others see and hear. Not only will aligning your thoughts with your actions build trust with your work colleagues; you’ll increase your own self-confidence and trust in yourself. And there is nothing passive-aggressive about that.

Focus On: Conflict

Manage a Difficult Conversation with Emotional Intelligence

Choose the Right Words in an Argument

Why We Fight at Work

Don’t Hide When Your Boss Is Mad at You

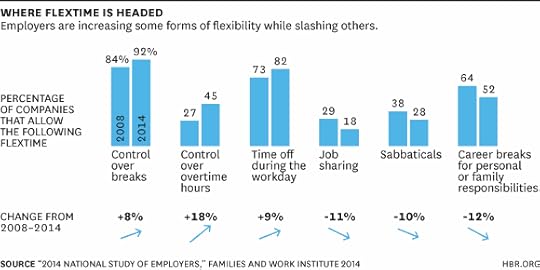

Flextime Is Declining, But “Flex Around the Edges” Is Up

Earlier this year, San Francisco and Vermont passed legislation that allows workers to ask for flexible work schedules without fear of reprisal. Are such “right to request” laws indicators of a rise in flextime? Or do they reflect a fear that flextime programs are being eliminated?

The answer seems to be a confusing “both.” New research from the Families and Work Institute (FWI) and the Society for Human Resource Management finds an “on the one hand, on the other hand” contradiction.

The good news is that some forms of flexibility — mostly allowing workers more control over when they start and end their workdays and more opportunities to telecommute — are on the rise. Since the FWI’s 2008 National Study of Employers, employers have continued to increase such options as control over breaks (from 84% to 92%), control over overtime hours (from 27% to 45%), and time off during the workday when important needs arise (from 73% to 82%).

At the Center for Talent Innovation (CTI), we call this “flex around the edges.” In interviews and focus groups conducted during the depth of the Great Recession, we found that companies that gave a little got a lot back: Employees reported greater engagement in their jobs, higher levels of job satisfaction, stronger intentions to remain with their employers, less negative and stressful spillover from job to home and vice versa, and better overall mental health.

Extended flextime, such as job sharing, part-time work, and sabbaticals, is an even stronger employee magnet. But these more substantial flexible work arrangements are being reduced. According to the 2014 FWI study, employers have slashed options that involve employees spending significant amounts of time away from full-time work, including sharing jobs (down from 29% to 18%), sabbaticals (from 38% to 28%), and career breaks for personal or family responsibilities (from 64% to 52%).

CTI’s global research into off-ramps and on-ramps — voluntarily leaving your job for a period of time and then returning — has found that flextime is a necessary tool for firms that want to remain an employer of choice in both developed markets and emerging markets, as well as for employers who want to retain existing talent and attract new talent coming into the workforce.

Among Gen Y talent, for example, having the opportunity to pursue an advanced degree, burnish their skills, expand their perspective by participating in a pro bono project, or simply take time out for reflection about their career path is key in choosing an employer: CTI research shows that 89% of Gen Ys stress the importance of having flexible options. “It’s critical to accessing the next round of workers,” explains Raafni Rivera, human resources manager of Employee Engagement Solutions at Cisco, whose Extended Flex program permits workers to take unpaid breaks of between 12 and 24 months.

More substantial opportunities for flextime are also crucial to retaining employees, especially those who are new parents or are dealing with eldercare issues. In our Off-Ramps/On-Ramps research, the vast majority of employees who left work for a period of time to focus on these personal commitments want to return to their career track: 89% of off-ramped women in the U.S. want to resume their careers, with similar numbers in Germany, Japan, and India. Yet, in all cases, barely half succeed. Meanwhile, some 69% in the U.S. say they wouldn’t have off-ramped if their companies had offered flexible work options, such as reduced-hour schedules, job sharing, part-time career tracks, or short, unpaid sabbaticals.

Retaining this pool of dedicated, experienced talent was the reason accounting firm EY launched a program formalizing flexibility nearly two decades ago. As recounted in a recent New York Times article, the accounting giant was losing women at a crucial moment in their careers — when they were eligible for big promotions, which happened to coincide with when they were starting families — and at a rate that was 10 to 15 percentage points higher than men. Now, the firm reports, women leave at a rate that is just two percentage points higher than men — and some 20% of men also sign up for the program.

We’re at a tipping point. As the economy continues to recover and workers have more choices about where to bring their talent and experience, companies must reconsider their inflexible stance on flexible work arrangements. What’s good for their top talent is also good for their bottom line.

Threats on Your Left Are Scarier than Those on Your Right

People tend to sense greater risk from a threat if it is to their left, rather than to their right, according to a series of studies by Himanshu Mishra, Arul Mishra, and Oscar Moreno of the University of Utah. For example, in research conducted in Bucaramanga, Colombia, pedestrians crossed a one-way street 4% faster if the traffic was approaching from their left and sat 17% farther from a threatening-looking homeless man in a row of outdoor chairs if the man was to their left. The reasons are unclear, but the effect may be due to brain structures that give people greater ease in perceiving left-to-right flow. The researchers point out that the findings could have implications for insurance companies: For example, consumers may be more willing to buy insurance if maps show that an earthquake-prone area is situated to the west (left) of their home cities.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers