Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1402

June 30, 2014

Encourage Your Employees to Talk About Other Job Offers

Why can’t employees speak honestly about their career goals with their managers? It’s because of the reasonable belief that doing so is risky and career-limiting if the employee’s aspirations do not perfectly match up with the manager’s existing views and time horizons. It seems safer to wait until another job offer is in hand, so that if one’s manager reacts badly to one’s ideas, there’s no danger of being passed over for on-going professional development, or worse, left unemployed. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: once an employee has gone far down the road with another potential employer, it’s hard for her to maintain a positive relationship with her current company.

Neither manager nor employee necessarily wants the current employment relationship to end, but because of the lack of trust and honesty, that’s precisely what becomes likely to happen with talented employees.

If you want to forge a high-trust alliance with your workforce, take a page from a popular clause in founder employment agreements — the “Right Of First Refusal” (ROFR). When a founder wants to sell stock in the company and has an offer to purchase some or all of the shares, the company has the right to exercise its ROFR and buy the stock at the offered price. This compromise reassures the founder (or employee) that the company can’t block the sale of stock while allowing the company to make sure it isn’t saddled with investors it doesn’t want.

We believe that an equivalent compromise can help improve the employer-employee relationship: the “Right of First Conversation” (ROFC). If an employee decides she wants to explore other career options, she commits to talking with her current manager first, so that the company, if it so desires, has the opportunity to define a more appealing job or role. This doesn’t mean that the employee informs her manager every time she receives a call from a headhunter—this kind of disclosure would be onerous for both employee and manager. Rather, the employee should initiate a conversation when she is seriously considering alternate job offers or career paths. Similarly, the employee should also approach the manager if she felt strongly that her current tour of duty no longer fits, and that without a change, she would feel obligated to start looking for another employer.

As with other aspects of the employer-employee alliance, the ROFC isn’t a binding legal contract. It’s an understanding between manager and employee that carries moral weight if violated.

Because the employer typically holds the power in the relationship, it’s up to the company to take the first step towards building the necessary trust. Managers need to say, “We don’t fire people for talking honestly about their career goals,” and truly mean it. Once employees believe that the company will live up to those words, managers can point out the benefits to the employee of granting them the Right of First Conversation.

First, an employee can benefit from frank career advice from a manager on specific industry opportunities. In a high trust relationship, a manager will not reactively denigrate competitors or “say anything” to keep an employee.

Second, perhaps the current company can upgrade the quality of the employee’s existing tour of duty. An employee who provides advance notice allows the company the time necessary to explore and develop more possible options and offers. If the company has weeks to match or exceed an offer from a rival, it has a much better chance of pulling together a counter than if it only had twenty-four hours to respond.

Finally, even if the company can’t present a compelling counter or the employee chooses to switch firms, the ROFC helps preserve the long-term relationship. The split can be made amicably, and on a timetable that works for both parties, honoring the mutual obligations and investment they have made in each other.

As a manager, would you rather manage a planned separation from an employee who has completed her final tour of duty? Or would you rather scramble to perform damage control on a sudden departure?

As an employee, would you rather depart amicably and become a valued member of the company’s alumni network? Or would you prefer to depart under a cloud of acrimony?

The Right of First Conversation represents a major departure from business as usual, but that’s precisely the point. The lack of trust between employer and employee is costing both parties. Adopting the ROFC helps both parties build trust and a longer, more fruitful relationship.

Do Men in Traditional Marriages Block Women’s Advancement?

In a study of male managers from U.S. accounting firms, those whose wives weren’t employed tended to evaluate female employees more negatively than did men whose wives held jobs: Responding to an online simulation in which they were asked to rate fictional candidates, men in traditional marriages rated women 2 points lower on a 4-point recommendation scale than did men whose wives were employed, says a team led by Sreedhari D. Desai of the University of North Carolina. There was no such discrepancy for male candidates.

The Power of Meeting Your Employees’ Needs

What stands in the way of our being more satisfied and productive at work? That’s the fundamental question we sought to answer in a survey we conducted with HBR last fall. More than 19,000 people, at all levels in companies, across a broad range of industries, have so far responded to the questions we posed.

What we discovered is that people feel better and perform better and more sustainably when four basic needs are met: renewal (physical); value (emotional), focus (mental) and purpose (spiritual). This isn’t surprising news, of course. Is there any doubt that when we feel more energized, appreciated, focused and purposeful, we perform better? Think about it: The opportunity and encouragement to intermittently rest and renew our energy during the work day serves as an antidote to the increasing overload so many of us feel in a world of relentlessly rising demand. Feeling valued creates a deeper level of trust and security at work, which frees us to spend less energy seeking and defending our value, and more energy creating it. In a world in which our attention is increasingly under siege, better focus makes it possible get more work done, in less time, at a higher level of quality. And finally, a higher purpose – the sense that what we do matters and serves something larger than our immediate self-interest – is a uniquely powerful source of motivation.

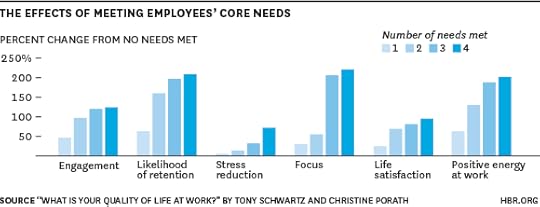

What’s surprising about our survey’s results is how dramatically and positively getting these needs met is correlated with every variable that influences performance. It would be statistically significant if meeting a given need correlated with a rise of even one or two percentage points in a performance variable such as engagement, or retention. Instead, we found that meeting even one of the four core needs had a dramatic impact on every performance variable we studied.

For example, when employees at a company perceive that any one of their four needs has been met, they report a 30% higher capacity to focus, a nearly 50% higher level of engagement, and a 63% greater likelihood to stay at the company. Even more interestingly, there is a straight dose effect associated with meeting an employee’s core needs – meaning that the cumulative positive impact rises with each additional need that gets satisfied. For example, when all four needs are met, the effect on engagement rises from 50% for one need, to 125%. Engagement, in turn, has been positively correlated with profitability. In a meta-analysis of 263 research studies across 192 companies, employers with the most engaged employees were 22% more profitable than those with the least engaged employees.

Interestingly, meeting three needs seems to have nearly as great an impact as meeting all four on most performance variables. The exception is people’s reported stress levels, where meeting a single need prompts only a modest 6% reduction in people’s stress, but meeting three reduces stress by 30%, and meeting all four leads to a 72% drop, The message to employers is blindingly obvious. None of us can live by bread alone. We perform better when the full range of our needs are taken into account. Rather than trying to forever get more out of their people, companies are far better served by systematically investing in meeting as many of their employees’ core needs as possible, so they’re freed and fueled to bring the best of themselves to work.

In practical terms, it’s possible to start making a considerable improvement without a lot of effort or expense, addressing one core need at a time. Consider the most basic performance variable, renewal, and its effect on people’s capacity. Only 20% of respondents said they were encouraged by their supervisors to take renewal breaks during the day. By contrast, those who were encouraged to take intermittent breaks reported they were 50% more engaged, more than twice as likely to stay with the company, and twice as healthy overall. Valuing and encouraging renewal requires no financial investment. What it does require is a willingness among leaders to test their longstanding assumption that that performance is best measured by the number of hours employees puts in – and the more continuous the better — rather than by the value they generate, however they choose to do their work.

June 27, 2014

Reframe a Moral Dilemma with Just One Word

When we’re faced with an immediate moral dilemma, most of us are so thrown off that we’re not exactly able to think in complete sentences. Once we’ve pulled ourselves together and we’re thinking more rationally, though, chances are we’ll ask ourselves something like “What should I do?” But there are advantages to making a one-word change to that question, turning it into “What could I do?” That’s because one of the difficulties of moral dilemmas is that they appear to force us to pick one path or another; the simple substitution of “could” allows us to think more expansively about possible solutions.

Harvard Business School doctoral student Ting Zhang, along with faculty members Francesca Gino and Joshua D. Margolis, report on a series of online experiments in which they asked participants to ponder such hypothetical dilemmas as whether to hire the (not very qualified) son of an important personage for an internship. They found that the “could” mental construction led participants to have better moral insight, enabling them to formulate solutions that resolved the tension between competing objectives. They generated solutions that didn’t simply select one path at the expense of the other (though we don’t get to hear how they would have solved the intern problem). —Andy O’Connell

Satisfaction Not GuaranteedWhen Doctors Tell Patients What They Don’t Want to Hear The New Yorker

There’s a lot of talk in American medicine about the value of listening to the “patient voice.” Patient-satisfaction scores now affect hospital reimbursements and even physician salaries in various inpatient and outpatient settings across the country. But as Penn cardiologist Lisa Rosenbaum points out in The New Yorker, there’s a disconnect between satisfaction and quality of care. Patients tend to become upset and extremely dissatisfied when doctors give them bad news or tell them to improve their lifestyles. In one study, the more patients understood about their poor prognoses, the less they liked their doctors.

Rosenbaum tells a great story of her own dissatisfaction with a doctor who informed her that the cure for her hamstring injury was to stop running for a while. She didn’t want to stop running, and pretty soon she started to notice the doctor’s faults: He typed with one finger. He had bad breath. She dumped him and found another who gladly injected her with steroids. Her satisfaction soared, until she realized—much later, when she still couldn’t run—that the bad-breath doctor had been right all along. —Andy O’Connell

Facebook = TebowSocial Media Fail to Live Up to Early Marketing HypeThe Wall Street Journal

The race to gather as many Facebook followers as possible has ended, at least for companies. Last May, for example, the Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company purchased ads that resulted in an avalanche of new fans. A few years ago, this would have been celebrated. But for the hotel's Vice President of Global Public Relations, Allison Sitch, the sudden increase wasn't positive at all. "We were fearful our engagement and connection with our community was dropping," she says.

And she's not alone. With new Gallup data showing that social media ads don't affect the buying purchases of 63% of people, companies are radically rethinking why they're on Facebook and how they can best reach and communicate with their customers. Reaching customers isn’t going to be easy: Facebook algorithm changes have resulted in an almost 10% drop in the number of fans who can see a company's posts, and posts are more likely to reach nonfans because of a premium placed on sharing. So what's a company to do? Monitor the heck out of what people are saying, as opposed to pushing content and ads. The NBA's senior vice president of digital media, for example, says her goal is to "give them more of what they're talking about."

Behind the Viral StoryA Job Seeker's Desperate ChoiceThe New York Times

If you're on Facebook, you've probably seen Shanesha Taylor's face. It's probably in mug shot form, her skin wet with tears. Taylor, of course, is the woman who left her kids in a car while she went on a job interview in Scottsdale, Arizona. She was charged with two counts of felony child abuse and suddenly became "symbol of both economic desperation and shirked responsibility." But she's a person, too, and in her first interview since the widely reported incident, Taylor describes her life: She had a good job as a mortgage loan officer until the economic downturn, and she exited the workforce in 2008 following the death of her grandmother. She was unable to recover, worked a series of low-paying jobs, and had two children. Then came the interview at a Farmers Insurance broker – and a babysitter she says wasn't at home. "Child care," explains the Vice President of the Institute for Women's Policy Research, Barbara Gault, "is often listed as the No. 1 challenge that gets in the way of women's work participation." Taylor describes her day this way: When the babysitter wasn’t available, she wondered, "What do I do now? What do I do now?"

Taylor is out of jail, but the charges are still hanging over her head. She finally has money — over $100,000 has been donated to her cause — and a three-bedroom home. But she doesn't have a job (which may be even tougher to obtain if she’s convicted) or her kids, who were removed from her custody. Nothing, it seems, will line up – even though, back in Scottsdale on that 71-degree day, it almost seemed as though things would finally come together for her.

It Could Happen to YouWhen Outsiders Oust Your Board: The Ramifications of ISS’ Influence on Public CompaniesChief Executive

As a provider of such things as proxy voting services and class-action claims-management services, Institutional Shareholder Services carries a lot of clout. (That’s putting it mildly — “Every public-company CEO is terrified of ISS,” Chief Executive’s Lynn Russo Whylly quotes crisis communications consultant Robert L. Dilenschneider as saying.) So a lot of attention was paid when ISS recommended that seven of Target’s 10 directors be replaced in the wake of the damage done to the retailer’s stock price by last year’s massive data breach. What to do? Whylly suggests Target take three steps: Reach out to ISS and try to work things out privately; remove the two or three directors it feels are most responsible and replace them with people who have some data-security experience; and do a lot more to acknowledge the problem and publicize the steps being taking to rectify it. Despite the obvious hit Target has taken, Whylly reports, infrastructure consultants do not feel that other CEOs are learning from its mistakes. —Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSLegalese

Thrown Out of Court (The Washington Monthly)

This Site is Building a Business on Making You Less Famous (Quartz)

Aereo and the Strange Case of Broadcasters Who Don’t Want to Be Broadcast (HBR)

Win Over an Opponent by Asking for Advice

What do an inflated surgical bill, a fuming real-estate developer, and a dreaded performance appraisal have in common? All can be mitigated with one simple gesture: a request for advice.

We seek advice on a daily basis, on everything from who grills the best burger in town to how to handle a sticky situation with a coworker. However, many people don’t fully appreciate how powerful requesting guidance can be. Soliciting advice will arm you with information you didn’t have before, but there are other benefits you may not have considered:

1. Advisors will like you more: Arthur Helps sagely observed, “We all admire the wisdom of people who come to us for advice.” Being asked for advice is inherently flattering because it’s an implicit endorsement of our opinions, values, and expertise. Furthermore, it works equally well up and down the hierarchy — subordinates are delighted and empowered by requests for their insights, and superiors appreciate the deference to their authority and experience. James Pennebaker’s research shows that if you want your peers to like you, ask them questions and let them experience the “joy of talking.” This is especially important because research shows that increasing your likability will do more for your career than slightly increasing competence.

One of us (Katie) recently put this to the test while dealing with a real estate transaction. After several phone calls to indifferent or discouraging county officials, Katie visited the Planning and Zoning office in person. Rather than pester the official with what would and wouldn’t be permissible, Katie asked for her advice on how she would handle the constraints. The official provided a bounty of insider information and guidance that Katie never would’ve obtained on her own. When Katie thanked the official for her invaluable insights, the official confessed that she was burnt out by constantly impeding people’s aspirations and dreams with zoning roadblocks. Katie’s humble request for the official’s expertise was revitalizing, and she in turn helped Katie deftly navigate what otherwise would’ve been a very difficult situation.

2. Advisors are able to see things from your perspective. Think about the last time someone came to you for advice. Most likely, you engaged in an instinctive mental exercise: you tried to put yourself in the other person’s shoes and imagine the world through their eyes. Our research has identified the extensive benefits of perspective-taking — it facilitates understanding and increases the odds of finding creative agreements in negotiations.

In another study, we simulated a performance appraisal and found that underperforming employees who asked for advice were able turn their bosses into better perspective-takers. This shifted the tone of a hostile performance appraisal towards cooperation and nearly doubled their chances of being recommended for promotion (31% vs 58%)!

3. Advisors become a champion for your cause: A third benefit of soliciting adversaries for advice is that they become your champions. When someone offers you advice, it represents an investment of his time and energy. Your request empowers your advisor to make good on their recommendations and become an advocate for your cause.

One of our favorite illustrations of this comes from one of our MBA students, Clara, who received a shocking $18,000 bill for a surgery that was performed at an out-of-network surgical center (even though the surgeon himself was classified as in-network). Detailing her strategy for negotiating the bill, Clara wrote, “I called Fran (the nurse). Deep down, I really believed this was her fault. But instead of approaching it that way, I asked for her counsel and guidance with the mess. Knowing her personality (interested in having control over her domain and running the show), I enlisted her to help me with the personnel at the Surgery Center. This made her feel important and she took the ball from there.” Thanks to the championing efforts of the nurse, Clara was able to negotiate not just a reduction of her bill, but a complete waiver!

This approach captured all three benefits of seeking advice: First, the nurse was flattered to have her authority acknowledged, quickly transforming the conversation from an argument to be won to a problem to be solved. Second, she was able to see Clara’s perspective and became sympathetic to her predicament. Finally, she felt empowered and committed to facilitating a resolution.

This same approach works in job negotiations. When one of us — Adam — negotiated his first professorship, he asked for advice from one of the professors he’d met during the interview. The professor immediately shared vital information (the university’s reservation price on salary!) and worked back channels with the dean to give Adam more research resources. The professor become such an advocate that she even adjusted her own teaching schedule to accommodate Adam’s desired teaching schedule.

Whether it’s a high-stakes monetary negotiation or winning support for a proposal, the simple gesture of soliciting advice can make you more likeable, encourage your counterpart to see your perspective, and rally commitment. The beauty of this approach is that it costs so little. So as you plan your next negotiation, consider how a targeted request for advice could turn an adversary into an advocate.

Focus On: Negotiating

The Best Negotiators Plan to Think on Their Feet

Two Kinds of People You Should Never Negotiate With

Why Women Don’t Negotiate Their Job Offers

Negotiating Is Not the Same as Haggling

Does Corporate America Finally Get What Working Parents Need?

At this week’s White House Summit on Working Families, President Obama and others made a moral case for changing the way we work. “Family leave, childcare, workplace flexibility, a decent wage – these are not frills, they are basic needs. They shouldn’t be bonuses. They should be part of our bottom line as a society,” the president remarked.

Yet there was also a strong business case for change, with vociferous and impassioned representation from our nation’s private sector. Bob Moritz, PwC’s US Chairman and Senior Partner, called on his peers to make significant changes, saying that “CEOs need to make this happen.” He reported that when PwC increased their flex options they saw higher productivity in return. When they transitioned to unlimited sick leave, the actual number of days that employees took as sick days declined. PwC offers back-up childcare and other family-friendly benefits because they have found that when employees are worried about issues outside of work, they can’t effectively focus on client needs.

Alex Gorsky, CEO of Johnson & Johnson, Lloyd Blankfein, Chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs, and Joe Echevarria, CEO of Deloitte (attending via video), all expounded on the importance for recruitment and retention of talent of not only implementing family-friendly policies, but for creating work cultures that encourage employees to live full lives. Makini Howell, Owner of Plum Restaurants, said, “Paid sick leave is pennies on the plate… The employee retention is priceless.” Blankfein described, as an example, Goldman Sachs’ “Returnship” program, which helps senior women re-enter the workforce after off-ramping. And he called out income inequality as a “destabilizing” force for companies and for society.

Raising the floor and addressing income inequality was also a major theme of the day, heard not only by labor representatives and progressive elected officials. Shake Shack’s CEO, Randy Garutti, reported that his employees deserve (and receive) $10/hour as a starting wage. Jennifer Piallat, CEO of Zazie, said, “Not only is it a moral decision to treat my workers well, but it’s also a financial decision.” Dane Atkinson, CEO of SumAll and serial tech start-up entrepreneur, asserted that there’s a business as well as a moral imperative in pay transparency and pay equity. In fact, as research from Zeynep Ton shows, investing in retail and service workers can benefit not only employees, but customers and the company as well.

It’s refreshing to hear leaders in the business world coming around on these issues because, at a 2000 Wharton Work/Life Roundtable, we made nearly identical recommendations, which have been repeated and reiterated in countless places.

What’s new, however, is that the ground is shifting. The Council of Economic Advisors released a report at the conference, noting:

Mothers are increasingly household breadwinners

Fathers are increasingly family caregivers

Women make up nearly 50% of the labor force

Women are increasingly our most skilled workers

Most children live in households where all parents are employed outside the home

Men as well as women are struggling to find a way to manage work and home responsibilities

As a result, and despite the downturn in the economy and high unemployment, employers are finding that in order to recruit and retain valued employees, they need to take non-work demands into account.

Men are also starting to speak up about family needs, and savvy employers are heeding the call. Enlightened entrepreneurs and CEOs are lauded while those with outmoded, Mad Men-era labor practices are vilified and losing business as a result. Work and life issues are increasingly and accurately understood as social and economic issues, not women’s issues, frills, or charity. As Mark Weinberger, Global Chairman and CEO of EY, smartly noted at the summit: “Women don’t want to be singled out and men don’t want to be left out.”

And while so much remains to be done, it’s heartening and inspiring to see so much executive attention to what has emerged as a national priority – making it possible for men and women to be free to choose the lives they truly want to lead.

Proven Ways to Earn Your Employees’ Trust

Trust is often talked about as the bedrock of a company’s success. Most people think about the issue in terms of customers: They have to believe in you and your products and services. But trust within the organization is just as important: Your employees must believe in each other. When they don’t, communication, teamwork and performance inevitably suffer. After New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger fired the newspaper’s editor, Jill Abramson, in May, he explained that he’d repeatedly warned her that she was losing the trust of the newsroom. But how do you build trust in the workplace?

What the Experts Say

Trust is an “evolving thing that ebbs and flows,” says David DeSteno, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of The Truth About Trust. And yet it’s essential to boosting employee engagement, motivation, and candor. Employees are more likely to follow through on goals set by a manager they trust and to be more forthcoming about the challenges they see on their level. “Managers will never learn the truth about a company unless they have employees’ trust,” explains Jim Dougherty, a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management and veteran software CEO. That’s why it’s so critical for managers to constantly reinforce their trustworthiness. Here’s how.

Make a connection

One of the most effective trust-building strategies is to create a personal connection. That’s especially true for managers. “As a person’s power increases, their perceived trustworthiness goes down,” says DeSteno; they seem less reliant on others and therefore less trustworthy. Counteract this view by getting to know the people on your team, and letting them get to know you. This might involve chatting about how you share a hometown or like the same sports team. It could also include hosting regular brown-bag lunches or occasionally taking a few calls with the customer service team. “Do something that makes them believe that you are one of them,” says Dougherty. That signals that “even though you are the boss, in the end you’re all in this together.”

Be transparent and truthful

Share as much as you can about the current health and future goals of the company. Otherwise, you’ll find yourself constantly battling the rumor mill. “If there is a void of information, employees will fill it and they will always fill it with negative information,” says Dougherty. There may be some data that you cannot share, like compensation, but regularly distributing other information — like financial results, performance metrics, and notes from board meetings — shows that you trust your employees, which in turn helps them have greater faith in you. Part of being transparent also involves having the integrity to tell the truth, even if it means you have to be the bearer of bad news. “If you can’t tell people the hard stuff, they won’t trust you,” says DeSteno.

Encourage rather than command

Employees know the difference between being given orders and being offered encouragement. “You don’t succeed in the long run by telling people what to do,” says Dougherty. “You have to motivate them to do it.” When employees feel empowered to succeed and believe that the goals of the company are aligned with their own, they’ll work harder and smarter. For managers, that means delegating tasks and granting as much autonomy as possible, while also making it clear what your expectations are and how performance will be measured. “People will trust you if you trust them,” says Dougherty.

Take blame, but give credit

No one wants a boss who hogs all the glory, but dishes out harsh criticism when times get tough. “The best way to get people to behave well is to give credit,” says Dougherty. That reinforces the sense that people are working toward shared goals rather than simply for a boss’s personal agenda. Instead of casting blame for layoffs or poor profits, stress that it is the company — and your own leadership — that need to improve. This signals that you “don’t believe different rules apply to you than apply to others in the organization,” says DeSteno.

Don’t play favorites

If there is a surefire way to lose trust, it’s by playing favorites in the office. “Any time there is favoritism, people will see it,” says Dougherty. “If you treat some people better than others, you totally blow it.” If you always give certain employees information or assignments first, or if you only ever ask a few out to lunch or to the ballgame, everything else you do to build trust will be undermined. You also want to avoid badmouthing at all costs, because it sends the signal that your public and private personas diverge. “People need to know that they are dealing with the true you,” says DeSteno. If they catch you criticizing a colleague behind his or her back, “they’ll assume that, as soon as they leave the room, you aren’t treating them well either.”

Show competence

If you aren’t good at your job, you can forget about earning employees’ trust. “Even if everyone likes you, you have to be competent to be trusted,” says DeSteno. That means regularly updating your own skills and following through on commitments. You should also avoid trying to be an expert in all things; those in the know will spot faked knowledge immediately. If you have the humility to ask questions and express an eagerness to learn, you’ll work smarter — and so will your employees. After all, “we can accomplish a lot more working with other people and relying on their expertise than we could alone,” says DeSteno.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Emphasize what you have in common — it helps employees believe that their goals are aligned with yours

Share whatever information you can — when people feel trusted, they’ll trust you back

Admit mistakes and accept responsibility

Don’t:

Give orders — motivating employees to succeed on their own will earn you trust

Badmouth anyone — people will automatically assume you’ll also speak poorly of them when their backs are turned

Fake knowledge — employees need to see you are competent enough to admit what you don’t know

Case Study #1: Keep the door open

When Jane McIntyre became CEO of the United Way of the Central Carolinas in 2009, she stepped into a scandal. The nonprofit organization was reeling from accusations of gross mismanagement, and Jane’s predecessor had left abruptly amid a controversy over her generous salary and retirement package. The community was outraged, donations were in a tailspin, and employees were confused and angry. Then the economic crisis hit, which necessitated layoffs and budget cuts. “It was a mess,” Jane says.

On her first day, Jane knew she had to do something meaningful to show the beleaguered staff that she was worthy of their trust. As the staff assembled to welcome her, someone asked her what her first priority was going to be. “There was this glass door that had been installed between the lobby and the executive offices,” McIntyre says. “The door was always shut. So I said, you see that door? It’s never going to close. And the staff burst into applause.”

Though Jane had to make difficult cuts in the months to come, she made sure that every decision was delivered with candor and honesty. She created compulsory all-staff meetings because she felt she “had to communicate face to face” with employees, especially when it came to delivering difficult news. She streamlined departments to create more connections among employees. And she reinstated the ability to send all-staff emails, a feature that had been disabled under her predecessor, to better share information across the entire company.

She also showed she was not above making cuts at the top. She made it known that her own salary was less than half of her predecessor’s. The board of directors, which had been accused of rubber-stamping excessive executive benefits, was cut from 67 members to 24. And she made accessibility her hallmark. “It helps so much if people know they have access to you,” she says. “It slows you down a bit, but it helps so much.”

Today, the organization is exceeding its fundraising goals and increasing grants to local charitable agencies. But Jane sees the progress she’s made in earning employees’ trust most clearly in the tenor of the all-staff meetings. “When I started, it was like you were in a graveyard,” she says. “There were no questions, no expressions. Now people laugh, they cut up, they have fun. There is camaraderie.”

Case Study #2: Meet bad news head on

Several years ago, Mike Volpe’s team was growing so rapidly, he could barely keep everyone’s names straight. In the span of nine months, the chief marketing officer for software company Hubspot saw his group grow from 20 to nearly 50 people. “I remember looking out at our team meeting and seeing so many new faces,” he says “It was a challenging time.”

In order to earn the trust of so many new people at once, Mike adopted a few key strategies. He reinforced the company’s policy of radical transparency, sharing data, goals, missteps, and milestones with everyone, at every level. “There’s no reason to keep a lot of things away from employees,” he says. “If you do, you are saying you don’t trust them.” He also gave his marketing team a high level of autonomy. “When you manage 15 or 20 people, you can be that person who approves things before they go out,” he says. “But once we started to grow quickly, I became a giant bottleneck. I knew I needed to trust the team to get things out. And we found the employees do a better job when you give them that authority and responsibility.”

He also regularly collected anonymous feedback via a tool called TinyPulse, which surveys employees on how they are feeling about their jobs. It was in those surveys that, several months ago, Mike started to see signs of a dip in trust. It was just after “three or four people who weren’t a good fit anymore” were let go around the same time, he says. “It wasn’t on purpose. It was just how the timing worked out.” But he could see from the anonymous surveys that people were now afraid for their jobs.

He immediately addressed the issue, both through the anonymous response feature on TinyPulse and in public “Ask Mike Anything” meetings. “I laid things on the table and took hard questions and didn’t give them sugarcoated answers,” he says. “I tried to take it head on and explained why it wasn’t indicative of a larger trend.” That honesty “really went a long way.” In surveys since, happiness metrics have fully recovered and even gone higher than they were in the period before the layoffs.

“I feel really good about how we navigated those waters,” he says. “It could have spiraled out of control, but because we had a system to track people’s happiness and a process to have honest conversations, we hit a pothole instead of falling into a crater.”

Is Your Company Ready for the Looming Talent Drought?

Even if your firm has a healthy employee base and a strong balance sheet, chances are good that it’s about to face a significant shortage of qualified managers. I reached that conclusion in 2007, after working with Nitin Nohria, the current dean of Harvard Business School, and colleagues at the executive search firm Egon Zehnder to gauge the effects of three factors – globalization, demographics, and leadership pipelines – on competition for senior talent in large organizations. We studied 47 companies, spanning all major sectors and geographies. The results were dire: Only 15% of the firms in the Americas and Asia, and less than a third of those in Europe, had enough people primed to lead them into the future. New survey and research data we have compiled show that the situation has grown even worse.

Globalization compels companies to reach beyond their home markets to do business and recruit and retain the people who can help them in that endeavor. The companies we studied in 2007 expected to increase their developing market revenues by 88% through 2012, and that trend has intensified. Ernst & Young, for example, currently predicts that 70% of the world’s growth in the next two years will come from emerging regions. Meanwhile firms based in those areas, most notably in China and India, are themselves expanding — and vying for talent — around the world.

The impact of demographics on hiring pools is also clear. The sweet spot for rising senior executives is the 35-to-44-year-old age bracket, but the percentage of people in that range is shrinking dramatically. In 2007 we projected that a 30% decline in the ranks of young leaders, combined with anticipated business growth, would cut in half the pool of senior leader candidates in that critical age range. A decade ago the shortage of rising leaders affected mostly the United States and Europe; however, experts say that by 2020 many other large economies, including Russia, Canada, South Korea, and China, will have more people at retirement age than entering the workforce.

The third phenomenon is related but much less well known: Companies are not properly developing their pipelines of future leaders. The failings we noted in our earlier study persist. In a 2014 PricewaterhouseCoopers survey of CEOs in 68 countries, 63% were concerned about the future availability of key skills at all levels. In recent interviews with 823 executives, Egon Zehnder found that only 22% view their pipelines as promising and only 19% consider it easy to attract the best talent.

Last month I asked 1,173 participants in an HBR webinar to evaluate how each of these three factors was likely to contribute to talent scarcity in their organizations, on a scale from irrelevant to crucial. Globalization was at least a substantial concern for 62%, demographics for 75%, and pipelines for a whopping 84%.

Each factor independently would create pressing demand for the right talent in the right place over the coming decade. Together they add up to a war for talent that means unprecedented challenges for most organizations. But they also present a huge opportunity for leaders determined to surround themselves with the best and to equip their organizations with the right hiring, retention, and development strategies (ensuring a strong focus on potential). The question is how your company stacks up against your competitors and what you can do to ensure that your talent practices are best in class.

Use this assessment to gauge your progress and obtain feedback on 15 specific practices that will help you succeed.

4 Ways to Decrease Conflict Within Global Teams

Working on a team scattered across the globe can be challenging. Differences in time zones, language, and cultural differences make it hard to get to know and trust team members. You can’t see what coworkers are doing or walk down the hall to resolve issues before they escalate. Sometimes, without the subtle cues you get working face-to-face, you don’t even know a conflict is brewing until it blows up. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

And yet in my research, I’ve seen plenty of highly functional global teams that don’t succumb to these pressures. They act as a unit, give one another the benefit of the doubt when things go wrong, and resolve issues promptly and constructively. There are four key things that characterize these distinct teams.

First, team members aren’t competing for their jobs. Every single team I’ve ever studied, in which people at one location felt threatened, was riddled with conflict. Members worried about losing their jobs and couldn’t bring themselves to build strong relationships with team members from across the ocean. In one U.S.-India team that Catherine Cramton and I studied, the U.S. team members were terrified that the work, and thus their jobs, would be transferred to India. As a consequence, they resisted collaborating with their Indian coworkers. Even during a face-to-face visit at the U.S. site, the Americans kept the Indians at arms length. Under these circumstances, it’s tough to build the rapport and trust that prevents conflict. Making sure that everyone on the team has a clear role and understands others’ distinctive contributions helps. Sometimes though, jobs are going away. In those cases, conflict may be inevitable, but can be mitigated somewhat by being forthright about the transition plan and timeline. In the face of a concrete plan, there’s less of a reason to compete with distant team members.

Second, harmonious teams have a shared identity. They feel like they’re “all in it together” and have a common vision not only for what they can achieve, but the important role each location plays in their success. In a study of global R&D teams, Mark Mortensen and I found that a shared identity significantly reduced conflict. One of the leaders described a team that had an enormous amount of tension until the manager created what he called a “ring fence” or boundary around the team that insulated it from external pressures, differentiating them from other teams, and creating a strong sense of the team and their mission. Another team from Catherine Cramton’s and my study held extended working sessions over video between the U.S. and Germany, creating the sense of being side by side as a unified team. These teams occasionally had conflict, but gave one another the benefit of the doubt and resolved conflict swiftly.

Third, these teams share a similar context or at least an understanding of their contextual differences. Mark Mortensen and I asked team members the extent to which their work tools or processes were incompatible, priorities were different, and information about what others were doing was incomplete. When differences were high and information incomplete, conflict soared. This effect was stronger when the team was more distributed.

The challenge on global teams is that the contexts are different — that’s unavoidable. But we found that as long as team members understand what is different, they’re less likely to blame each other for incompatibilities. One way to foster that understanding is to encourage and support team members (not just managers) to visit other locations and, importantly, not only headquarters. Catherine Cramton and I found that site visits were a powerful way to understand how processes and practices varied and build rapport that endured long after the travelers returned home.

Finally, informal, unplanned communication dramatically reduces conflict. When team members pick up the phone, chat or text one another outside of scheduled meetings, and share information on what’s going on — that helps to convey information about processes and how they might be changing, build rapport, and reinforce a shared identity. The teams that had at least one person initiating contact with distant team members on a regular basis had a more casual, fluid interaction and could deal with issues that arose without conflict spinning out of control. Again, this effect was stronger — interpersonal conflict went down — when the teams were distributed across more work sites.

Some argue that conflict is good, especially conflict that is focused on the task, not the people.That’s still under debate, but evidence shows that conflict is particularly destructive for global teams. It is too hard to detect, too hard to resolve, and too hard to recover from. These four approaches help eliminate conflict before it derails the team.

It Pays to Put Your Team in a Good Mood

Three-member teams on which at least 1 person was in a good mood were more than twice as likely to collectively solve a murder-mystery puzzle as teams on which all members were in neutral moods, according to an experiment by Kyle J. Emich of Fordham University. That’s because people in good moods are more likely to seek information from others and to share their own knowledge. So if you start a meeting with a funny story or do something else to put people in a good mood, you may get better exchange of information and better decision making, Emich suggests.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers