Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1401

July 1, 2014

Leadership Is About to Get More Uncomfortable

Employees used to know just your name, your face, your business reputation.

Now they know your salary, your hometown, your connections on LinkedIn, how much your house is worth. They know more than ever, and you’re under pressure to share more than ever, too – 76% of global executives think it’s a good idea for their CEO to be on social media.

And along with this increased transparency, you’re held accountable for areas you know less about: new technologies, new markets, new cultures and geographies representing new stakeholders. It’s no wonder .

Good leaders have always stepped out of their comfort zones, but converging global megatrends are putting more pressure on those at the top to navigate a faster, more complex, more integrated, and more transparent business world.

In our recent book, “Leadership 2030: The six megatrends you need to understand to lead your company into the future,” we examined the repercussions of the convergence of major forces like globalization, climate change, increased individualism, and accelerating digitization.

Among our findings is that leadership in the future will involve increased personal and business-level discomfort. Leaders will have to cope with the blurring of private and public life – and they will have to forge new relationships with competitors and employees. This requires new skills and mindsets. Ego is on its way out.

Technology alone offers several sources of discomfort. Leaders will increasingly be called to evaluate and implement new technologies they don’t always understand and can’t control, from the cost-benefits of data automation to balancing consumer concerns with data mining opportunities to gauging the commercial value of bitcoin and other new concepts. As connectivity-enabling technology and virtual workplaces change how people interact, leaders must engage employees across cultures and business roles through new mediums. Leaders must acquire digital wisdom, even if they lack digital knowledge.

The combination of digitization with globalization and consumer demands for personalized products will complicate the usual processes and relationships. Competitors will be recast as allies, as rival companies will have to work together to achieve more complex technical innovations. Such “co-opetition” will require leaders to maintain a difficult dual perspective – rivals must be simultaneously seen as both vital partners and market threats.

But possibly the biggest adjustment for leaders of today is a power shift that is requiring major changes to how they think and work. Many are accustomed to command-and-control, to fear over love, and to “lead, follow, or get out of the way.” But hierarchies are flattening as power moves away from top internal management and toward employees and a proliferation of external stakeholders. Companies must now appeal to a plethora of global consumer markets, each with distinctive attitudes and desires.

Leaders motivated by power over others will not thrive in this new world.We will see more “altrocentric” leaders, who understand that leadership is a relationship and will therefore primarily focus on others rather than themselves. Adept at engaging rather than commanding, they see themselves as just one integral part of the whole. Altrocentric leaders will be capable of long-term vision encompassing both global and local perspectives.

David McClelland points out that both emotionally intelligent leaders and their egocentric counterparts tend to be motivated by power; they enjoy having an impact on others.The difference is in the type of power driving them: Egocentric leaders tend to be concerned only with personalized power – power that gets them ahead. Altrocentric leaders, on the other hand, derive power from motivating, not controlling, others.

The altrocentric leader who is intrinsically motivated by socialized power, and who draws strength and satisfaction from teaching, teambuilding, and empowering others, will be able to handle the increased pressure of tomorrow’s business environment. They understand that they need not “have all the answers” themselves, and this mindset and willingness to turn to others for help [accurate? Like competitors and employees?] better equips them to handle the stress of the uneasy chair.

All leaders will see life become more chaotic and overwhelming, and their struggles and management will be more visible than ever. Egocentric leaders will have a difficult time evolving, if they even can, and will be unable to thrive in such discomfort. Organizations need to develop leaders who are motivated by altrocentric leadership. They will be better prepared to succeed in 2030 and beyond.

Leading Across Borders Takes More than a Multicultural Background

I recently had a phone conversation with Cosimo Turroturro, who runs a speakers’ association based in London. Simply on the basis of his name, my assumption before the call was that he was Italian. But as soon as he spoke, starting sentences with the German “ja”, it was clear from his accent that he was not.

Turroturro explained, “My mother was Serbian, my father was Italian, I was born in Italy and raised largely in Germany, although I have spent most of my adult life in the UK. So you see, these cultural differences that you talk about, I don’t need to speak to anyone else in order to experience them. I have all of these challenges right inside myself.”

I laughed, imagining Turroturro having breakfast alone and saying to himself in Italian, “Why do you have to be so blunt?” and responding to himself in German, “Why do you have to be so emotional?” But then I got to thinking about what it would be like to work for Turroturro in a multicultural team.

It seems rather obvious that any global organization would be lucky to have a lot of Cosimos wandering their corridors. And there has been a spate of research in the last few years detailing the upside to the Cosimo profile.

My colleague, Professor Will Maddux, has demonstrated in a number of correlational and experimental studies that managers who are bi-cultural or who have lived in more than one country score higher on creativity tests than those who have lived in only one culture. That’s good news for any global innovation project that has just hired a Cosimo.

Another of my colleagues, Professor Linda Brimm, calls people like Cosimo “global cosmopolitans.” She shows these multicultural types quickly assess and integrate into new cultures and are therefore highly valuable assets in any international organization. In addition, “global cosmopolitans” are usually multilingual, which makes it easier to build relationships and connect with clients and employees around the world.

That sounds like even better news for Cosimo, especially if he has a German, an Italian, a Serb, and a Brit on his new team. In fact, who better to lead the team? With his experience of living in a variety of countries and a multi-cultural family, he can help his team to decode their cultural differences, coach them to be more cross-culturally flexible, and offer strategies to improve their effectiveness — all in their own languages too.

Well, maybe not. Don’t assume, just because Cosimo speaks three languages at the breakfast table, that he is the best person to lead your global interactions.

First of all, Cosimos are often so culturally flexible themselves, having been adapting from one culture to another since they were infants without giving it a thought, that they don’t understand why working across cultures would pose challenges for the rest of us. They may have never thought much about cultural differences, and although they switch cultural contexts as easily as some people change clothes, they might barely realize they are doing it.

As a result, people like Cosimo sometimes lack empathy for those who are caught in a trap of cross-cultural inefficiency or frustration. Time and again, I have had someone like Cosimo attend my classes, only to annoy everyone else in the room with a comment like: “Working across cultures is easy! Why can’t my team just get over it?!” That is definitely not the type of coaching a global team needs when differences in cultural values are hindering collaboration.

My next example concerns an American, Tim Shen. Tim has Chinese parents and was born in Dubuque, Iowa, where he spent his childhood before going to the University of Chicago. Tim looks Chinese and speaks Mandarin fluently. He’s had a terrific career as an executive so far in the US, so a lot of American companies would naturally turn to someone like Tim when they need a leader for their Chinese operations.

Tim also thinks this shouldn’t be much harder than leading Americans, because he thinks of himself as Chinese… Chinese and American, that is. But when Tim arrives in Wuhan, China, it doesn’t take long for him to learn that he is not a Chinese businessman. He thinks and leads and communicates like an American, albeit in perfect Mandarin. And he is not a cultural bridge, able to move back and forth between the Chinese way of working and the American way of working. How can he be when he has never worked in China?

This is very confusing to everyone, not least Tim’s Chinese staff, who don’t cut him a lot of slack: after all, he sounds Chinese and therefore should know better. They complain bitterly of his lack of leadership skills and inability to understand and address the implicit needs of the clients and workforce. Tim comes to realize this would probably be a lot easier if he did not look Chinese, and he wishes he had an American accent when speaking Mandarin. At least then people would understand why he doesn’t lead like a Chinese person. They would stop to explain the cultural norms to him and help him understand all the cultural nuances that are passing completely underneath his radar.

Cosimo and Tim very well may be the best people you can find to run your global operations. But don’t assume, just because they are multicultural, that they will have the know-how to coach your global teams on cultural differences, or that they will become cross-cultural mentors for your global organization. If your company needs a globetrotting executive who will be in Shanghai on Tuesday and Bogota on Thursday, a Cosimo or a Tim will probably be a good bet. But if you are selecting someone to run a global team or organization, look for successful experience in leading a multicultural group, rather than going straight for the most multicultural person you can find.

Elon Musk’s Patent Decision Reflects Three Strategic Truths

In a June 12th blog post that made instant waves, Elon Musk, founder and CEO of electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer Tesla Motors, declared: “Tesla will not initiate patent lawsuits against anyone who, in good faith, wants to use our technology.” The words stood in stark contrast to most of the other recent news about patents – the headlines of wars being fought in the courts by, for example, Apple, Samsung, and Google Android.

The Internet’s response was to ask a collective “Why?” Why would the leading company in EVs voluntarily open up its technology to competitors? Analysts and pundits offered a number of theories – none of them mutually exclusive, but all suggesting different motivations:

Elon Musk’s personal impassioned desire to see the entire category grow at the expense of gasoline cars. This is the most explicit rationale he offered in his blog. “Our true competition is not the small trickle of non-Tesla electric cars being produced,” he remarked, “but rather the enormous flood of gasoline cars pouring out of the world’s factories every day.”

A long-term view towards driving down costs from electric vehicle parts suppliers, spurring the development of more widespread EV infrastructure, and thereby making EVs more appealing and affordable – all of which would ultimately benefit Tesla.

A strategy of enticing other automakers to adopt Tesla’s standards in order for Tesla to become the supplier of choice for other automakers when it comes to batteries and specialty parts for EVs.

A hope for patent reform – using Tesla’s visibility as a way of provoking a better conversation that might ultimately change the system.

A mere bid for publicity, considering that Tesla hasn’t, in any formal way, cut off the possibility of future lawsuits or opened up any of its proprietary secrets. (Patents are already in the public record).

One way or another, the announcement looks like a canny move. In the five days following the blog post, Tesla’s shares were up 10%, and, as the Financial Times reported, major automakers like Nissan and BMW are already lining up to talk with Tesla about collaborating on charging networks and standards.

Personally, we don’t presume to know Elon Musk’s mind. But here’s the insight we do take away from the episode. The fact that any of these theories could be true – and based on the share price movement, all of them are being applauded – says three important things about the nature of industries and competition today:

Industries are increasingly irrelevant; it’s now the ecosystem that matters.

Traditional automakers define themselves by their role within the automotive industry. They are adept at selling cars through dealership networks, and know how to drive down costs with suppliers. Their position within the industry defines their business strategy. We’ve plotted changes in the auto industry in the US, Germany, and Japan over the last 100 years; while strategies have certainly changed over time, the differences between eras essentially boil down to varying degrees of vertical integration and the ever-shifting balance of power between automakers and suppliers.

By contrast, disruptors like Tesla (or, for that matter, Google) gain a new advantage by understanding, leveraging, and ultimately staking a claim in the broader ecosystem, drawing heavily on innovation from outside traditional industry boundaries. They can – and will – do things differently. Witness, for example, the way Tesla is selling their Model S directly to consumers as opposed to replicating the traditional dealership model. Is Tesla even an automotive company? Not exactly – despite the product it markets and sells to consumers. In reality, according to analysts, Tesla is at its essence a fuel cell company: “In our view, Tesla has always essentially been in the cell business.”

Successful companies don’t play a role; they excel at an activity.

What’s the difference between a role and an activity? A role is defined by contractual and business relationships within an industry – being an aftermarket parts manufacturer, for example – whereas an activity is an essential and indispensible function within the broader ecosystem based around a set of specialized capabilities. (Michael Porter has written about “activity-based strategy” to mean the set of internal firm-wide activities that make up the value chain of a company. By contrast, here we are referring to the market-wide activities the company performs in its broader ecosystem.)

Having studied many different industries and ecosystems (as part of the research that yielded the recent book Big Bang Disruption), we’ve concluded there are only four essential market activities that matter today – and that the best bet for a company to make itself disruption-proof is to excel as one of these:

Inventors originate breakthrough components for use in an assortment of products.

Producers manufacture those components at scale.

Assemblers construct and distribute a final market-ready product.

Designers innovate new ways to bring together existing components in a unique fashion.

By adopting an “open source” position with regard to its intellectual property, Tesla is hoping to secure its position as the indispensible Inventor within the broader electrical storage and battery ecosystem, especially as the inventing relates to automotive applications.

Why did Tesla specifically choose to specialize around the Inventor activity? Because it recognizes that established Assemblers and Producers (automakers and their OEM suppliers) already dwarf it in size, and will most likely continue to do so. And, as Musk’s announcement makes clear, the company is prepared to accept other automakers as Designers in the electric vehicle space to grow the market. What Tesla wants more than anything is to cement its original innovations in the center of the broader ecosystem, especially when it comes to battery storage and charging – a positioning that would enable further growth into an array of other traditionally distinct industries that will increasingly be drawn into the battery and storage ecosystem.

“Activity focus” is the new strategic focus.

Orienting around a market activity isn’t just for disruptive new entrants. It’s a path that’s available to incumbents, as well, although the changeover is often far from easy. Consider an example from a different industry: semiconductor chip maker Intel. The company’s industry role as a leading component innovator and manufacturer was threatened with the decline of the PC market. To lessen its reliance on the fortunes of the PC industry, Intel took a gamble on the broader ecosystem. In 2010, the company began to experiment with a new “foundry” business model, entering into contracts that granted other chip companies – even some who were associated with competitors – access to Intel’s underutilized manufacturing facilities.

Some analysts pointed out the apparent folly of pursuing a market that, they estimated, was capped at $7 billion – an amount which, they argued, “just isn’t all that much to a company like Intel.” But by looking just at the market potential, these analysts missed the longer-term implications of Intel’s ecosystem play. In starting its foundry business, Intel did not just open up a new revenue stream; it repositioned itself as an indispensible Producer within the broader chip ecosystem.

Tesla Motors and Intel Corporation have placed what we call “Big Bang Bets” around focused market activities – often to the consternation and confusion of industry analysts. Time will tell how these bets pay out. The lesson for incumbents of all kinds is not so uncertain: They should think carefully about their more rigid industry strategies, and how those leave them prone to the sudden irrelevance that is the reality of big-bang disruption.

The Magical Power of Touched Objects Really Works, If You Believe

Research participants with intuitive thinking styles demonstrated higher creativity after handling papers supposedly touched by creative people and lower creativity after handling papers said to have been touched by less-creative people, say Thomas Kramer of the University of South Carolina and Lauren G. Block of the City University of New York. Those who believed the papers had been touched by creative people came up with about 67% more ways to use a paperclip than those who thought the papers had been touched by people with low creativity (there was no such effect among participants with highly rational thinking styles). The findings suggest that intuitive-minded employees may perform better on assigned tasks when using pens or computers previously used by creative or intelligent people, the researchers say.

What Momentum on Climate Change Means for Business

Climate change is real — as in actual, factual, and tangible. And it’s really expensive. This is the clear message from “Risky Business,” a new report issued by former U.S. treasury Secretaries such as Robert Rubin and Hank Paulson and other bigwigs like Michael Bloomberg.

Their report is just one of many drumbeats for action on climate — drumbeats that have gotten much louder in recent weeks. Four former EPA chiefs, all Republicans, went to Congress to ask their party peers to take action, for example. And Hank Paulson, George W. Bush’s Treasury Secretary, recently wrote an op-ed called “The Coming Climate Crash” as a prelude to the Risky Business report. He likened the growing climate crisis to the fiscal crisis of 2008, a mess he had to deal with firsthand. This Republican and former Goldman Sachs exec actually called for a tax on carbon. Let that sink in for a moment.

The story coming from these unusual messengers is not subtle about how expensive climate change is and will continue to be. We’re taking out an “interest-only loan,” the report says, with cumulative interest that will burden future generations. In a neat metaphor, “Risky Business” calculates that there’s a 1 in 20 chance — equal to the chances of “an American developing colon cancer” — that more than $730 billion of coastal assets will be at high risk in the coming years. And whole swaths of the country will face extreme heat — months of days above 95 degrees, which could seriously impact agricultural and labor productivity (imagine construction and other outdoor work in dangerous heat).

These long-term numbers are just for scale and to, well, scare us into action. But the real message of the report is that there are serious economic impacts today. Extreme weather from climate change is, they say, “already costing local economies billions of dollars.”

So finally, real bipartisan pressure and consensus are building. What does that mean for business?

First, questioning whether climate change is even happening is moving fast to the far fringe. The discussion is shifting, thankfully, from if we should tackle it to how — as one CEO I work with said recently, “I know this is a problem… I just don’t know what to do about it.” Over the coming months and years, it will become even less acceptable — to employees, customers, and investors — for business people to stick their heads in the increasingly hot sand on this issue. Investors in particular are starting to notice the massive risk to business and acting accordingly — see Barclays’ downgrading the bonds of U.S. utilities because of growing competition from solar and distributed energy generation. Business leaders who want to take action and show their investors and customers that they “get it” should step forward now.

Second, there will be more regulation on carbon around the world. The recent coal rules the Obama administration issued are just the beginning. (The 30% reduction from utilities demanded by 2030 is not even particularly aggressive. Ten states have already hit the goal.) It’s not just the U.S. — the day after Obama’s announcement, China said it would cap CO2 emissions starting in 2016.

Third, and most important, business needs to change how it operates fundamentally. When you dig past all the political wrangling and theater around climate change, you reach a very serious challenge. Asking government to act, as many new voices are doing, is a great start. But we need business to lead in the areas it excels at — driving deep, heretical innovation in products, services, and business models; connecting with and inspiring customers to change their behavior; allocating capital to the best ideas, and much more.

But we’re going to have to redefine “business as usual,” a shift I’ve called the big pivot. Companies will need to think about the longer term — at least more than a quarter at a time — if they want to plan for multi-year and multi-decade risks and opportunities. They’ll need to set goals based on science and make investment decisions with a broader sense of return on investment than they normally use, to include benefits like risk reduction, business resilience, relevance in society, and attracting and retaining the best talent. And we’re going to see new, unusual partnerships across normal party and competitive lines. All of these pivots are underway, but they need to move much faster.

Luckily, we have most of the solutions we need now. Renewable energy is reaching scale quickly and companies are coming together along value chains to work on big challenges — for example, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Unilever, and others have been working for years on changing technologies for refrigerating drinks, something that relies on high global warming HFC gases today.

But even if the options for building low-carbon lifestyles and businesses are growing, transformation can be hard. Who knows what gets people over a hump to see the need for real change. Hearing from unlikely sources, like Treasury Secretaries, might do the trick. Certainly the growing economic costs are getting clearer. It’s time for business leaders to make climate action a — if not the — core priority for business.

June 30, 2014

The Paying-It-Forward Payoff

You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours. But if you scratch my back, am I any more likely to scratch someone else’s?

Most of us are familiar with direct reciprocity – the idea that people respond to kind actions directed toward them with other kind actions. But generalized reciprocity — “you help me and I help someone else” can be a bit trickier to measure. New research, however, shows that it might be possible for companies to encourage such generosity among employees.

Researchers Wayne E. Baker, a professor at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, and Innovation Places’ Nathaniel Bulkley focus in on two common types of generalized reciprocity: paying it forward and rewarding reputation. Paying it forward, they write, means that people’s motivations are driven by “positive affect: ‘You help me, and I feel grateful, so I pay it forward by helping a third party.”

Rewarding reputation is a little less full of glitter and rainbows. As the researchers explain, it’s when “helping others is driven by strategic action and intentional reputation building.”

Yet much of the research on rewarding reputation suggests it might be a much stronger and longer-lasting motivating force within organizations compared to paying it forward. For instance, at a firm like IDEO, write Baker and Bulkley (drawing on research by Andrew Hargadon and Robert I. Sutton), where “designers with reputations for helpfulness are more likely to get help themselves compared to those who have not been helpful,” designers “build reputations strategically with future self-benefit in mind.”

So Baker and Bulkley designed an experiment in which MBA students were required to post five questions to a group message board and respond to 15 such requests from others. This was worth 10% of their grade, and those who went above and beyond the quota would not receive extra credit.

The researchers found that the more responses posted to the message board in total, the higher the probability a group member would respond to another’s brand new post. This supports the hypothesis that the more help a person receives from others, the more likely that person is to help someone else. Second, the more responses a person wrote in the week before making a request of his own, the more likely others were to answer his question. This supports the idea that helping others will make it more likely that they themselves will receive help – rewarding reputation did have an impact.

Here’s where things get interesting. There was an even stronger impact for paying it forward.

There are a few reasons for this, the authors say. To start, rewarding reputation only really mattered for recent reputation. In fact, they write, “reputation effects decayed thereafter and actually turned negative for past reputation.” This wasn’t something the researchers were expecting, but they posit that a “good citizen” is often seen as someone who helps others on a regular basis, and that an old reputation for helpfulness doesn’t do anyone any good. It’s what they refer to as the “What have you done for me lately?” problem.

Essentially, paying it forward is cognitively easy, at least compared to remembering who is helpful, and how often. “The sole requirement [of paying it forward] is that a participant be aware of his or her own experience,” they write, “which is simpler and more salient than observing others and keeping track of what they do.” Few people have the mental energy to deal with the constant scorekeeping that rewarding reputation requires.

And yet Baker and Bulkley don’t discount rewarding reputation; rather, they see the two types of generalized reciprocity as working strongly together, albeit with paying it forward coming out slightly on top. In fact, the researchers observed cycles of reputation-building and paying it forward that suggests “over time, rewarding reputation and paying help forward may have created a virtuous cycle of cooperation.” They continue: “The fact that almost 9 of the 10 participants continued to use the system after the quota [had been attained] suggests that a ‘tipping point’ may have been reached. If it had not, then a vicious cycle might have ensued, and cooperation would have plummeted.”

But it didn’t. Interest in one’s reputation did not overcome paying it forward. The two mechanisms managed to interact harmoniously, with paying it forward lasting longer over time.

So how can organizations harness this? The authors suggest IDEO’s regular brainstorming meetings enforce norms of asking for and offering help. Such gatherings need to occur regularly because of the “what have you done for me lately?” dynamic. The researchers also encourage using gratitude as a tool, as Southwest Airlines does with the “agent of the month” award that recognized employees who have helped others do great work. Google, they write, “uses a peer-to-peer bonus system that empowers employees to express gratitude and reward helpful behavior with token payments.” Smartly, this policy has a built-in pay it forward mechanism because “a recipient of a peer-to-peer bonus is given additional funds that may only be paid forward to recognize a third employee.”

And if your company is globally dispersed? Take a cue from ConocoPhillips, which has online knowledge sharing communities where members post business problems and others offer solutions. Since 2004, the researchers write, the company has realized over $100 million in savings using this system, built simply off the idea that, in the right situations and with very little handholding, people really are willing to help others out.

The Hobby Lobby Decision Could Affect a Majority of U.S. Workers

The U.S. Supreme Court today ruled that the government cannot force “closely held” corporations to offer insurance coverage that provides birth control to employees, a stipulation of the Affordable Care Act passed by Congress in 2010.

Closely held corporations — firms in which 50% of stock is owned by five or fewer people — are by definition closely linked to a few core owners, whose rights the Court sought to protect. As the majority wrote:

“The purpose of extending rights to corporations is to protect the rights of people associated with the corporation, including shareholders, officers, and employees. Protecting the free-exercise rights of closely held corporations thus protects the religious liberty of the humans who own and control them.”

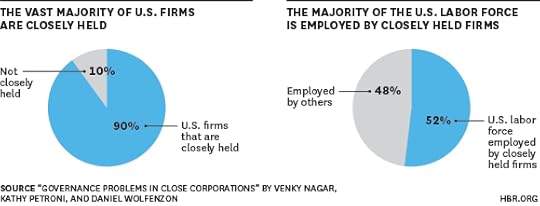

But while the ruling may seem limited in that it only speaks to closely held firms, it in fact applies to more than 90% of U.S. companies, and even to a narrow majority of workers.

The effect that the ruling will have is unclear, though the Wall Street Journal has already reported on some businesses that plan to stop providing contraceptives as a result of the ruling.

Such a trend could help reverse the steady increase in contraceptive coverage, which has risen from 68% to 84% since the passage of the ACA.

The backdrop for firms’ benefit decisions are the “two opposing forces” of “strong demand for employee benefits by jobseekers and existing employees alike, and the ongoing rise in the cost of benefits, particularly health insurance” according to a recent survey by the Society for Human Resource Management.

For most closely held firms, religious exemptions will take a back seat to this balancing act, between costs and talent. According to a recent Journal of the American Medical Association poll, 69% of Americans support the Affordable Care Act’s policy of mandated contraception coverage, and only 7.8% supported all benefits except contraception — the Hobby Lobby position.

What Makes People Follow Reluctant Leaders

In today’s knowledge-based and highly-automated enterprises, companies look for the cleverest and most capable people they can find. But having hired such talent, organizations face a challenge. Places full of highly mobile and in-demand workers operate more democratically. Leaders don’t necessarily gain power by dint of high rank; they need to earn it every day. How do they do that? And, for the would-be leader in an organization like this, what are the secrets to rising to the top?

For the answers, it’s useful to look at how leaders succeed in professional service firms, traditionally structured as partnerships. These have always been places where the leaders are those who most impress their clever peers rather than their superiors. A new study by professors Laura Empson (Cass Business School, London) and Johan Alvehus (University of Lund, Sweden) sheds light on who reaches the position of maximum authority in these firms and why. They went deep into three international firms with reputations for excellence – one a law firm, one a public accounting firm, one a management consultancy – conducting over 100 face-to-face interviews with people working within them.

The leaders in these firms, they discovered, are characterized by three traits. First, they are exemplary professionals, judged by their colleagues to be capable of doing the core work of the firm at the very highest level of quality. In the words of Empson and Alvehus they have gained “legitimacy to lead through market success.” As important as the model of excellence they offer is the very fact that they are seen (and trusted) by the professionals they lead as “one of us.” One senior partner put it this way: “I think that professional service practitioners … will accept almost unlimited decision-making and authority from someone they think understands the things they are going through.”

Second, these leaders enable autonomy while retaining control. Clever people do not want to be told how to do their jobs, but they appreciate the importance of coherence, and the power of colleagues pulling together rather than working at cross purposes. They grant permission to lead to colleagues they believe will allow room for grown-up and capable people to get on with their work, while ensuring that the firm is heading in the right direction and maintaining high standards.

Third, and even tricker to manage, effective leaders are given credit for their political skills, both as they rise through the organization and as they operate at the top. As one senior partner said: “I think the level of politics and personality here is different because you have a sort of cadre of highly paid (partners) … people who own the client relationships. So there is something about needing to keep all 500 partners happy which brings a level of politics, which you wouldn’t get if we were an engineering company or a pharmaceuticals company.”

It would be hard not to note the parallels to the workings of political parties and the delicate process of “seeking high office.” In these firms, elections are held, requiring candidates to issue manifestos, give speeches, and participate in debates. There is much talk of “the electorate,” “constituents,” and “mandates.” Aspiring leaders of professional service firms must build and sustain consensus among their colleagues, make trade-offs between competing interest groups, and offer incentives to individuals to lend their support. The process is subject to the lobbying and bargaining which occurs in any other political arena.

But the respect for political skill is striking, because in these workplaces Empson and Alvehus also frequently encountered abhorrence of political behavior, and a professed belief that effective leaders are “above politics.” The leaders who succeed, the researchers conclude, are capable of interacting politically while appearing apolitical. Without being caught doing anything so grubby as scheming or plotting, they manage relationships and power with aplomb. This requires a combination of social astuteness, interpersonal influence, networking ability, and apparent sincerity.

Put these three traits together, and the sum is a kind of paradox: the people most enthusiastically granted the power to lead by their peers are individuals who seem reluctant to do so. They relish doing the core work of the firm, serving clients with distinction. They are happy to grant autonomy. They don’t exhibit the political behavior associated with raw ambition. They might not go so far as to say (as General Sherman did), “If nominated, I will not run; if elected, I will not serve.” But they display the attitude toward leadership that it is not work one would choose, only a responsibility that should be shouldered by “one of us.”

Perhaps it is only appropriate that such a paradox of an employee, the autonomous follower, can only be directed by another paradox: the reluctant leader. As enterprises of all kinds depend increasingly on clever, capable talent, they will have to embrace the same paradoxical arrangement. In today’s well-regarded professional services firms, they can find the models for enabling knowledge workers to combine their energies and accomplish great things. And they can find the secrets to enjoying a brilliant career in an organization where so many are brilliant.

Everything You Need to Know About Giving Negative Feedback

There’s a lot of conflicting advice out there on giving corrective feedback. If you really need to criticize someone’s work, how should you do it? I dug into our archives for our best, research- and experience-based advice on what to do, and what to avoid.

Never, ever, ever feed someone a “sandwich.” Don’t bookend your critique with compliments. It sounds insincere and risks diluting your message. Instead, separate your negative commentary from your praise, and don’t hedge.

Schedule regular check-ins with your direct reports, so that giving feedback — both negative and positive — becomes a normal part of the weekly routine.

Don’t lump your critical feedback together with discussions of pay and promotion — as in typical year-end evaluation. This creates a toxic cocktail of emotions even the most mellow employee will have trouble managing. Instead, make these separate conversations.

The adage “praise in public, criticize in private” is an old management mantra. But sometimes, you have to be critical in public. Holding people accountable sometimes means discussing performance issues with the group, even if it feels uncomfortable.

Ask permission. This may sound odd — especially if you’re the boss — but you can tip people off that a critique is coming (making them more receptive to hearing it) if you start the conversation with, “Can I give you some feedback?”

Avoid jumping to conclusions or seeming like a bully by sticking to the facts. For instance, if employees are leaving early and showing up late, they could be having a family emergency or a health issue. Simply state the behavior you’ve observed and let them explain what’s going on.

Try framing your critique in terms of the positive result you want to achieve, rather than as what’s wrong with the person. Make it about the impact the employee could achieve by working differently. Ask “What are your goals?”

Be specific about the new behavior you’d like to see.

If you’re delivering some particularly hard-to-hear news, consider giving the person the rest of the afternoon off. Studies have shown that top performers are especially vulnerable to major setbacks. Show compassion not by softening the blow with false praise, but by giving bad news straight and then offering some breathing room.

If the person you’re giving feedback to gets defensive or lashes out, keep your preferred outcome and preferred working relationship in mind. You can’t prepare for every possible thwarting mechanism someone might throw at you, but you can control your reactions.

Recognize that everyone wants corrective feedback — yes, even Millennials and even experienced, expert workers. Consulting firm Zenger Folkman found that while managers dislike giving critical feedback, all employees value hearing it — and often find it even more useful than praise.

There’s one important caveat here, however, and that’s the ideal praise-to-criticism ratio. While we may not be willing to admit it to ourselves, we do need to hear praise. And studies of both the most effective teams and the most happily married couples have shown that the ideal ratio is about five compliments to every criticism. So do shower your team with kudos — just don’t do it at the same time you’re critiquing them.

And when you do offer plaudits, praise effort — not ability. Carol Dweck’s well-known research has shown that’s the best way to keep people motivated and it makes criticism feel less threatening and personal. After all, if you’ve been told your whole life, “You’re so smart!” a rebuke might make you wonder, Am I dumb now? Focusing your praise on behaviors — “You guys really put a lot of attention to detail into this” or “I’m so impressed with how hard you worked to get this done on time and under budget” — means that when you have to deliver some corrective feedback, people are more likely to take it in the same vein rather than as a personal attack.

How We Transformed Marketing at Electrolux

Marketers are racing to create seamless customer experiences that make it easy for consumers to engage at every touchpoint as they navigate the “decision journey” and beyond. Despite this revolution, leading appliance makers have been slow to adapt to the ways people learn about and purchase appliances. Electrolux was no exception – until recently.

Many consumers think of us as a vacuum cleaner company – and indeed our first product, in 1919, was a vacuum. But today we’re a $15 billion global consumer and professional appliance firm that includes Frigidaire, AEG, Molteni, Electrolux, Zanussi, and Eureka among its brands. As we were a product-centric organization, the shopping experience had played a supporting role, with individual elements of the experience managed by different organizational silos. When online emerged it became a new silo, followed by mobile and social. The organization was locked in a structure that made it difficult to connect and integrate all the different ways that a person gathers information, makes a decision and receives support — online and offline. In 2012, Electrolux leadership decided this had to change.

Our transformation centered on the consumer. Research uncovered many underappreciated consumer purchase drivers and barriers. We were surprised by how much the introduction of new store formats, new product types, and new online, social and mobile tools were frustrating consumers because they did not connect to each other. With this growing complexity, the journey was becoming increasingly fragmented and difficult. Recognizing the need for integration, Electrolux’s digital, trade, brand and product marketers worked together to create a cohesive experience from pre-purchase, to the purchase itself, to post-purchase service and beyond.

To this end we eliminated silos between functions including marketing, sales, IT, consumer insight, and innovation and established “consumer experience teams” in each business and region. These teams include consumer insight, brand, product, retail, digital, social, and consumer care specialists who now closely work together to create integrated consumer experiences and launch plans. We also moved responsibility for the post-purchase experience into marketing — all of the services, onboarding, registration, and add-on purchases and support that people receive after they buy.

In addition, we took a fresh look at how our marketers are organized globally. We moved a large group of digital marketers from the corporate center into the consumer experience teams. And we set up new, regular sharing sessions to improve cooperation among regions.

Temporary “pilot” teams in each region are now an important part of the new organization. They pilot innovations in the consumer experience such as launching a new digital recipe planning app or creating an easier way to register products under real market conditions, and they help implement promising innovations at roll out. Team leaders focus on translating the pilots into repeatable programs for other regions.

Governance is clear. Marketing leaders representing each region meet monthly to coordinate activities and share best practices across the globe. Individual regions build and execute integrated customer experiences and launch innovations based on the way consumers shop in their markets.

We’re supporting this organizational transformation through training initiatives, process improvements, new tools, and a focus on building a more consumer-focused culture. Capability building puts an emphasis on developing “transformation champions.” In 2013, the top 50 global marketing leaders engaged in a hands-on three-day training session focused on the vision, strategy and plans to transform the appliance shopping experience. An additional 250 marketing leaders are undergoing similar training right now. Month-long online “adventures” that tackle specific customer-journey challenges began rolling out May 2014. The first adventure challenged participants to learn more about how digital is changing consumer shopping behavior and to identify better ways to use digital technologies in appliance shopping.

An organization-wide crowdsourcing program is just one of the tools we’ve introduced to accelerate product and consumer-experience innovation and build a more consumer-focused culture. A few months ago over 6,000 employees globally crowd-sourced more than 1,500 ideas in 72 hours with record levels of collaboration and engagement. Three finalists entered pilots this spring. Each year we celebrate the best of our consumer experience ideas through a live conference held in our corporate headquarters in Stockholm. Experience innovators are feted by the most senior leaders in the Group and recognized throughout the company.

Our transformation is driving growth. In the first quarter of 2014, The Electrolux Group delivered its ninth consecutive quarter of organic growth. The organizational changes have dramatically increased the number of products and experience innovations that exceed predetermined goals for meeting consumers’ needs. Our pilot teams are really taking hold. In the past six months, we’ve launched a branded food and home decor inspiration site, an online recipe site/app, a mobile augmented reality app to demonstrate the benefits of new products such as steam ovens and an in-store product-selector web site that helps consumers find the best washer and dryer for their needs. Our market research shows that shopper experiences are improving. Speed to market has accelerated.

These organizational changes have been challenging — as is always the case when you knock down silos, shift resources, and push the culture in new directions. But the payoff has been demonstrable and rapid. In just two years, Electrolux has pulled from behind in the omnichannel race to become a leader in its sector.

The New Marketing Organization

An HBR Insight Center

How Sephora Reorganized to Become a More Digital Brand

CMOs and CEOs Can Work Better Together

Marketers Need to Think More Like Publishers

Brands Aren’t Dead, But Traditional Branding Tools Are Dying

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers