Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1400

July 3, 2014

Before You Start a Business, Listen to Your Ego

When I meet entrepreneurs I always ask them why they started their companies and they almost always say something like “because I had a great idea the world needed.” But when you peel back the layers you discover far different motives – motives they don’t want to acknowledge because they’re directly related to primal desires and fears. Yet the well-being of their businesses depends on their understanding those real motives.

A talented coder I know — let’s call him Abe — is characteristic of many other talented individuals who start a business saying that they had a great idea the world needed. Abe’s talent attracted investors but he deeply disliked babysitting customers and supervising non-coding positions. He was miserable. His investors fired him. Only after he was fired did Abe’s soul-searching lead him to realize that his real motivation was to work only on projects he enjoyed. Only after the fact did he realize that by bringing in outside investors his life became exactly the opposite of what he wanted, as he was forced to work only on what everyone else wanted him to.

A serial entrepreneur I know, a brilliant mind coupled with a difficult personality we’ll call Bruce, burned through four startups until he acknowledged his powerful motivation, which led to his success on his fifth try. Bruce had initially started companies when he thought he saw opportunities to make a lot of money, only to professionally implode each time the opportunity proved elusive. Consulting an analyst after the fourth failure helped Bruce realize that it wasn’t making money that was he really wanted; he needed to satisfy his hyper-competitive need to be top-dog at whatever he did. He needed to start a business in an area where his skills were world-class rather than simply targeting the latest lucrative industry, playing to his strengths and fulfilling his desire to compete aggressively. Understanding his need to be top-dog also helped Bruce realize that he wanted to get all the help and VC money he could to help him grow his enterprise as fast as possible. Bruce’s fifth startup now has a billion-dollar valuation and he could care less that his VCs will make a major share of the money.

I personally could not have succeeded as an entrepreneur had I not realized, with the help of an executive coach, that I had a powerful motivation of “needing to be needed.” This unrealized motivation had led me to exhibit behaviors that made me a poor team player when others did not ask for my input and advice. Once I realized my core motivation it changed my life, driving me to be an entrepreneur in an area where my expertise and advice were highly regarded. At my startup, iSuppli, I created an organization structure that revolved around weekly status meetings and quarterly business reviews that allowed me to feel clued in and integral to every part of the business, without micromanaging or holding back our growth. This one insight was central in my creating a company whose valuation had topped $100 million when it was bought in 2010.

In these cases and in virtually all cases, the motivations that drive an entrepreneur to prevail are typically selfish. Unfortunately, selfish motivations are hard to acknowledge because we all want to justify our actions in socially acceptable terms. On the other hand, honestly acknowledging your selfish motivations is typically very empowering and helps to focus you on the things that need to be done to fulfill your desired goal. An important side effect of acknowledging your selfish motivations is that it will give other people more confidence in the success of your endeavor, since they understand why you are taking on the challenge.

An entrepreneur’s true motivation can thwart their success if it is left unstated or conflicts with the interests of the business. Because changing your deepest motivations is almost impossible, you must find a way to put them to work for you by aligning your motivation with your new venture.

The Fukushima Meltdown That Didn’t Happen

Charles Casto, recently retired from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, on how smart leadership saved the second Fukushima power plant. For more, read the July–August 2014 issue of HBR.

Boards Still Don’t See the Value of Digital

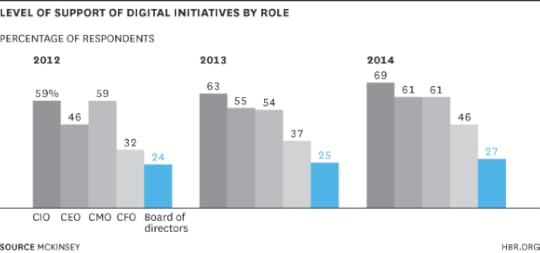

Companies across the world are ramping up their digital initiatives, according to a new survey from McKinsey, with the C-suite increasingly leading the way. “Digitization has become a critical asset in many companies’ quest for growth,” write the report’s authors, noting the increased involvement by CEOs and other top executives.

There’s only one problem. Boards don’t seem interested.

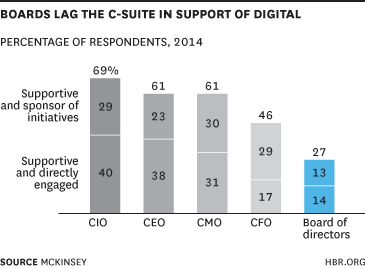

When it comes to digital initiatives, the board of directors seems to be lagging. The vast majority of survey respondents indicated that their company’s board not only wasn’t directly engaged in digital projects, but was not even a supportive sponsor.

Perhaps most troubling, board support for digital projects has barely budged in the last three years, unlike support from senior executives which has grown meaningfully.

For firms looking to make the transition to digital but lacking supportive boards, it may be time to think about replacing a director or two. Research has shown that companies that replace three to four directors every three years outperform their peers. And even a couple digitally savvy board additions can go along way toward building support for new initiatives.

The flip side applies to board members: those that show no interest in digital are more likely to be pushed aside. Digital growth is appropriately a priority for a diverse swath of organizations, and boards need to get with the program.

What Made a Great Leader in 1776

The ordinarily decisive George Washington was paralyzed by indecision. It was the summer of 1776, and the Continental Army was being routed by the British in New York. Sick from dysentery and smallpox, 20 percent of Washington’s forces were in no condition to fight.

Militia units were deserting in droves. General Washington had exhausted himself riding up and down the lines on Brooklyn Heights, attempting to rally dispirited troops. Prudence dictated retreat – to preserve the hope of fighting another day. At the same time, though, Washington viewed any defeat as damage to his reputation and a stain on his honor.

There are any number of good reasons to read Joseph J. Ellis’s splendid little book, Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence. Ellis is a wonderful storyteller. His prose is lucid and succinct. Revolutionary Summer is a riveting exposition of exploded myths and excruciating dilemmas. For one thing, Washington — while by no stretch of the imagination the “little paltry Colonel” the British constantly derided — was not the near deity we often read about in American history books. He only reluctantly accepted the advice of aides for what turned out to be a brilliant tactical retreat in August of that summer, and a turning point in the war.

Indeed, the Americans, writes Ellis, were frequently “improvising on the edge of catastrophe.” Which helps to explain why Ellis’s book is a such a terrific case study in leadership. Here are the lessons I take away from it for leaders today.

First, success often depends on a team with complementary skill sets, frequently involving different temperaments and work styles. As a leader you have to assemble the talent you need, and live with and mitigate the shortcomings of respective team members. Thomas Jefferson, drafter of the Declaration of Independence, was superb with a pen. He was a notoriously poor public speaker, however. John Adams was brilliant, courageous, and resolute. He also suffered extreme mood swings and could be dangerously hubristic. (Furious over desertion rates, Adams suggested to an aide that they execute in each regiment every tenth man as a lesson.) Then there was Thomas Paine, the perfect spokesman for their cause. “I could not reach the Strength and Brevity of his style,” remarked Adams, “nor his elegant Simplicity nor his piercing Ethos.” Yet Adams also contended that Paine was “better at tearing down than building up,” a reference to what would happen after British rule.

The takeaway? If you are clear about your objectives, and focused on precisely what you need to develop and execute the elements of your strategy, you can assemble an unbeatable organization. Hire for common purpose, yes. But don’t hire clones.

Second, leadership is tested most by a dilemma — a situation that requires a choice between two or more equally unfavorable options. It is leadership’s job to arrive at decisions, and to do so in a way that aids their implementation. Adams insisted on postponing deliberations on what the new nation would look like, fearing that early splits between advocates of a confederation of sovereign states and champions of a consolidated union would undermine the war effort. He also wanted to postpone discussion of the fundamental disagreement between the northern and southern states over slavery. Some 500,000 individuals, roughly 20 percent of the population at the time, were African American, and nearly all slaves. The institution of slavery was an appalling contradiction of everything the revolution stood for. But Adams was convinced that all other political goals would be lost if independence from Britain were not first achieved. (Adams also resisted his wife Abigail’s plea to advance rights for another disenfranchised group: the female population that could neither vote nor, if married, own property.)

Here, my takeaway is that essential to leading is being clear about priorities. Not all decisions will involve the profound moral dilemmas faced by Adams and his peers. However, every difficult decision has a downside and produces unintended consequences, some of which are simply impossible to foresee. Do your due diligence. Then plunge in and push ahead.

Finally, a gem nearly all of us ignore: good leaders need good sleep. There were many challenges that plagued George Washington. His soldiers were, writes Ellis, “a motley crew of marginal men and misfits, most wearing hunting shirts instead of uniforms, spitting tobacco every ten paces.” The array of considerations Washington had to make was daunting. To mention but one, there were roughly 15,000 cattle, sheep, and horses on Long Island. What to do? Leave them? Confiscate the livestock to prevent them from falling into British hands? If yes, how would confiscation impact the allegiance of the farmers? New York was already infested with loyalists. Washington was swamped by a thousand such details. One wonders, though, whether a chronic sleep deficit was as serious a challenge as any individual issue he faced.

According to Ellis, at one point Washington was so exhausted he was unable to file a crucial report to the Continental Congress. He told John Hancock that in 48 hours, “I had hardly been off my Horse and never closed my Eyes, so that I was quite unfit to write or dictate.” Was a lack of sleep at least in part responsible for Washington losing his customary discipline and control on the battlefield? At the battle of Kip’s Bay — between what is now 32nd and 38th streets in Manhattan — Washington “struck several officers [with his riding crop],” repeatedly threw his hat to the ground, and initially resisted his staff’s desperate efforts to get him to exit the field — as British infantry was just 50 yards away.

There’s nothing weak or wimpy about getting rest, even — and especially! — in crisis situations. Today we have the science to back this up. Sleep deprivation can produce myriad deleterious effects, including frustration, confusion, irrationality and indecisiveness. According to sleep researchers, sleep helps us with alertness, perception, memory, reaction time, and communication. Specifically, sleep deprivation diminishes regional cerebral metabolism in the prefrontal cortex, that part of the brain responsible for higher-order cognitive processes. The result: impaired judgment, and high-risk behaviors.

I myself recall managing the case of a kidnapped Iraqi journalist in Baghdad several years ago. Our team got the reporter out alive, with high marks in a review from the U.S. military hostage negotiators who had assisted throughout — except that I was criticized sharply for going two weeks on 3-4 hours sleep per night. That was a well-intentioned behavior that might well have put the entire operation in jeopardy, the de-brief emphasized.

The lesson should be obvious: Balance is key. Work like a maniac, if you will. But no matter the stakes, if you don’t rest your body and mind, something (or someone) will be jeopardized.

I’ll end with my most general (and perhaps obvious) takeaway from reading Ellis: leaders looking for insights on how to do their crucial work better will find them in the vivid accounts of past triumphs. We don’t read history because it repeats itself. We study history because it reveals and inspires.

And all the better if it sometimes amuses. When the commander of British forces, still hopeful for early surrender, told Benjamin Franklin that he would lament American defeat like the loss of a brother, Franklin replied, with a bow and a smile: “My Lord, we will do our outmost to save your Lordship that mortification.”

Innovation Is Marketing’s Job, Too

When I took over as chief marketing officer at GE, the mandate from CEO Jeff Immelt was to make marketing a vital operating function that could drive organic growth. We realized early on that it wouldn’t be enough for marketers just to focus on advertising and external messaging. We were in a unique position to integrate ideas and teams across the company, and to draw insights from the outside world. So we signed up to fight in a bigger way for the market and GE’s place in it.

GE’s best path to organic growth is to continue the world-changing innovation it has always been known for. The ethos of restless invention has driven us since the days of Thomas Edison. In marketing, we resolved to fuel that innovation, and also to make our own efforts as creative and valuable as the products coming out of our R&D labs.

Now, after more than a decade of experimentation, I can share the formula we’ve developed. Tested and proven at GE, it might be similarly effective for other marketers looking to create value and drive innovation in their businesses.

Go to new places. GE’s marketers have to be explorers, seeking out new places and bettering our understanding of what people need in every corner of the globe. We’ve found this to be true across industries, but particularly in health care. It’s wonderful to be trusted to create sophisticated products for highly trained physicians at world-class medical centers. But if we also want to compete in the world’s fastest growing markets, we also need to see that, in many places, power supplies are intermittent and the medical professionals interacting with patients are mainly midwives and practitioners with limited training. Marketers can provide that kind of insight and fight for better outcomes for customers in the markets we serve.

Here’s an example of what can happen when we do: GE now sells ultrasound machines that are portable and durable enough to simply be trekked in to wherever they are needed. Using them is almost as simple as flicking the on/off switch; red and green lights serve as indicators. And therefore, pregnant women in remote locations are better served. For GE, the value doesn’t end there. When marketers are empowered to understand where the world is going, the fresh understanding they deliver of what customers value and how to deliver that value can be scaled across the company.

Shape the market early. The really good innovations – the ones that change the world – need to be explained before they’re accepted. Recently, for example, I’ve been posing this question to our markets: What happens when billions of machines come online and start communicating? As we enter the age of the Industrial Internet (GE’s term for that invisible web connecting all these brilliant machines), it’s up to marketers to define for regular people and business customers how this new reality will drive different outcomes. At the same time, our explanatory powers can push our own company to do its best thinking about the possibilities for connecting industrial technology, analytics, and user experiences.

Because this is the kind of breakthrough innovation that GE excels at, one of our mantras in marketing is “mindshare before market share.” We’ve had to achieve that with ecomagination and, more recently, with GE’s innovations in advanced manufacturing. It has meant becoming a content factory – telling stories across media and methods from data to videos to social media. Through good storytelling and by connecting with others who share interests in getting those stories out, we help shape the markets in which GE’s offerings will be able to deliver value. We anticipate what our customers – future and present – will need, and describe it. Long before customers are clamoring for specific solutions, marketing is setting the stage.

Incubate new businesses and models. Part of marketing’s mandate at GE is to find ways the company has not thought of before to promote ongoing innovation. That can be as simple as creating a “protected class” of ideas that are therefore given more time to prove their value. This kind of treatment gave rise to the Durathon battery, which provides backup power for cell towers in parts of Africa where the electricity supply is intermittent. The technology began life as a project to create a battery for a hybrid locomotive; only later was it adapted for other applications. Another boost to innovation via marketing has been FastWorks, a program designed to integrate startup culture into our DNA. It simplifies development and gets products to market faster.

Invite others in. At GE, we don’t want to solve every problem alone. Partnerships are the path to speed and scale. That’s why we’ve established connections with the data competition site Kaggle, the cloud-based engineering platform GrabCAD, and the invention factory Quirky. We’ve taken to market several creations that came to us through Quirky inventors, including the sleek Aros air conditioner. These opportunities evolved from marketing people asking simple questions: Are we open to creating meaningful new partnerships? Are we experimenting often and in new spaces? Demolishing the barriers between innovators at GE and makers outside the company has expanded our creative territory, and it’s just one more way we’re fighting for the market.

Back when Edison was alive, there were still a few mad scientists around trying to invent a perpetual motion machine. Of course, given the laws of physics, it isn’t possible. But when a marketing department helps to fuel the very innovations it promotes, it can feel like it is. Perpetual-motion marketing – marketing that connects the company’s offerings to markets, and in making those connections generates new energy around invention – is a minor miracle we can achieve. And for a company whose future depends on innovation, it might be the only way to go.

The New Marketing Organization

An HBR Insight Center

How We Transformed Marketing at Electrolux

Marketers Don’t Need to Be More Creative

CMOs and CEOs Can Work Better Together

How Sephora Reorganized to Become a More Digital Brand

The Hobby Lobby Decision: How Business Got Here

Monday’s Hobby Lobby decision by the United States Supreme Court marks the first time the government has recognized that some for-profit corporations have religious rights. The ruling is based not on the First Amendment of the Constitution, but on a 1993 statute. Usually, Supreme Court decisions clarify matters of law for the lower courts; but in this case, the mess of tea-leaves in the ruling has thrown commentators into a confused frenzy.

Experts on religion and the workplace, too, are unsure what this means for businesses and the broader business climate. “We don’t know where this will take us,” admits Diana Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion at Harvard and Director of The Pluralism Project. “Time will tell,” says David Miller, Director of Princeton University’s Faith & Work Initiative.

But there are several larger trends that may indicate the lay of the land. One is the growing treatment of corporations as organisms that have rights and points of view. As Mark Tushnett of Harvard Law School said in an interview, “Corporations have a lot of constitutional rights as surrogates for individuals…Yes, [the Hobby Lobby decision] moves the line a little, but the line was already pretty far in the direction of corporate rights anyway.”

Another development that seems to have led, at least in part, to this moment is the bring-your-whole-self-to-work movement. These calls for authenticity have not explicitly focused on religion, but it is inevitable that if you are a religious person, your faith is closely tied to your sense of self. As Wharton ethics and legal studies professor Amy Sepinwall put it, “A state that takes seriously its obligations to respect religious free exercise has to understand that individuals are not going to want to leave their religious convictions at the corporate office door.”

A third major trend is the push for a more moral form of capitalism. Whether you call it creating shared value, conscious capitalism, the triple bottom line, social business, or something else, it has mostly focused on secular ethics. But it is easy to see that believers’ moral codes would be deeply informed by their faith. The question, as Eck put it to me, is: “At what point does an ethical purpose get to have an exemption from national laws?”

It seems likely that we’ll be wrestling with more of these questions in the future. I asked Eck if there had been a shift in how Americans conceive of religion that had helped lead to this moment.

“On the Christian right, the articulation of faith is much more public than ever before. But there are also other public advocacy groups — Christian, Jewish, Muslim and interfaith — concerned with a range of public affairs, from domestic poverty to international conflict. At the same time, for many younger people, faith is no longer primarily about ‘belonging,’ that is, belonging to a community that attends the same worship services or observes the same holidays. We also have seen the rise of a religiousness, a spirituality, of ‘seeking,’ that is much more individualistic.”

If that trend towards every-believer-for-himself continues, it may make it more difficult for courts to adjudicate similar cases — something the Hobby Lobby decision seems destined to produce. Says Princeton’s Miller, “Surely it will open the door to future requests by other companies who have a religious identity of some sort.” Wharton’s Sepinwall sees future courts trying to gauge the seriousness of a company owner’s religious beliefs, something the lawyers and justices in the Hobby Lobby case purposely steered clear of. “You would want to look to various pieces of evidence that support the company’s asserted religious conviction…that the company’s stores are closed on Sundays, for example.”

That sounds like an awful lot of work for the lower courts – which may mean that regardless of who actually won Burwell vs. Hobby Lobby, the real victory will go to the lawyers.

How to Hire a CEO You Won’t Want to Fire

A lot of CEOs are being shown the door lately. In the apparel industry alone, we’ve just seen the end of American Apparel’s Dov Charney and the ouster of Lululemon Athletica founder Chip Wilson – plus the installation of interim CEOs at Target and JC Penney following their previous leaders’ firings. These companies are in trouble, and their boards must select new CEOs under highly charged circumstances.

At least some of them are bound to make the mistake we’ve seen so many times: pushing ahead with a sense of urgency around their new CEO selection, and allowing their deliberations to be overtaken by strong wills and unexamined emotions.

Here’s what they should do instead. First: take the time to arrive collectively at a short list, not of candidates but, first, of criteria. An open and rigorous debate over CEO criteria is the most important step a board can take with succession. Then: commit to a process by which the potential leaders they consider will be honestly, consistently assessed against those criteria and a winner will emerge.

Why is the early narrowing of criteria so important? From the outset, it reinforces the reality that no CEO candidate is perfect. All of the available options will have noticeable strengths and weaknesses. The board’s challenge is to decide what deficits it can live with (usually because they can be compensated for by the rest of the leadership team), and which two or three criteria are non-negotiable must-haves.

The alternative, and unfortunately the usual route, is to compile a laundry list of laudable qualities. While none of them is easy to argue against, collectively they have no power, because the list doesn’t allow the best candidates to emerge. Worse, a list that calls for everything gives every director something to point to as they lobby for their own favorite. Someone prevails and others, eager to wrap up this sensitive and time-consuming process, capitulate. From the outside the process might look like solid work, following best practice. But the board has essentially abdicated its most important responsibility.

Consider the case of a specialty retailer whose CEO was retiring after a long, successful run. The retiring leader advocated strongly for an executive he had groomed for the job, in his own image. But the board recognized that the company’s environment was changing dramatically, thanks to global expansion, greater online competition, and customers’ evolving expectations of their shopping experience. Diligently, the board drew up all the criteria it felt it should consider.

Clearly it was time for a CEO who could handle omni-channel complexity, but on the board’s wish list, that was just one item among many. Among the others was merchandising experience, which the heir apparent, like his mentor, had in spades. Reluctant to oppose a leader who had dramatically increased shareholder value, the board folded under pressure and ratified the CEO’s pick. The result was disastrous, as the company suffered numerous missteps in rolling out new channel strategies and overhauling back-end systems.

When a board never engages in open debate over which attributes matter most, not only does it fail to connect succession to what the company most needs; it neglects to give the incoming CEO guidance about where to focus his or her own efforts and in what areas it might be best to delegate.

Boards, and companies’ governance processes, are idiosyncratic; exactly how to focus on what’s really needed in the next CEO will depend on the firm. But, at a high level, it is a three-part process: Start with an exploration of likely scenarios for the company in the next several years. Get input from executives, high-potentials, and outside stakeholders on how those conditions will most challenge and create opportunities for the company. Then develop a profile limited to a few must-haves. This process is usually enhanced with the departing CEO’s involvement, as long as the board shows leadership.

Greater focus brings better results. A global energy company was struggling and seemed unlikely to survive the industry’s looming consolidation. With its CEO preparing to retire with a mixed legacy, the board at first generated a list of fifteen things at which the new leader should excel, ranging from expanding into new markets, to driving a Six Sigma-based culture of operational excellence, to getting a major facility project back on track. Rather than work from this list, however, the urgency of the company’s situation drove the board and CEO to debate which goals were most important. They narrowed the list to three: defining a visionary strategy to survive consolidation, driving a culture of accountability so the company could deliver on promises to investors, and developing a strong bench of executive talent. They consciously left out operational goals, because most directors agreed the CEO could rely on the existing business unit heads, and a capable COO could also be hired from outside.

That effectively ruled out the heir apparent, despite the fact that some directors had felt he was “owed” the job. While his strengths were significant, it was undeniable that the three key areas of need were weaknesses for him. The board hired an external candidate, who over the next few years made some transformational acquisitions, kept the company independent, and greatly boosted the stock price.

There Are Risks in Having the CEO’s Pals on the Board

Ties of friendship between corporate directors and CEOs can compromise firms’ integrity, but public disclosure of the ties can make the problem worse, according to research in the American Accounting Association’s Accounting Review. In a study of 56 board members, 46% of those who were asked to imagine being directors of a fictitious firm whose CEO was a friend said they’d be willing to substantially cut R&D if it meant triggering a hefty bonus for the chief executive (compared with 6% of those who were asked to imagine that the CEO wasn’t a friend). Those who imagined disclosing the friendship were willing to cut 66% more than those who imagined keeping the friendship secret—apparently because disclosing the friendship gave directors the feeling they had a moral license to reward the CEO, the researchers say.

July 1, 2014

How to Delegate Your Email to an Assistant

In the early days of the internet, email natives loved to trade tales of executives who asked their assistants to print out emails so they could read and respond to them on paper. Now we all use email, and assistants are a seemingly rare commodity. But they can still play a useful role in managing your messages.

That kind of support is no longer limited to the lucky few who have administrative help on staff, either. Thanks to the emergence of the collaborative economy, in which people can access services on a pay-for-use model, there are more and more options for getting administrative support, whether it be using a virtual personal assistant service like Zirtual, hiring a part-time assistant through Craigslist, or having more traditional access to administrative support through your company.

An assistant can reduce the burden of email management in ways automated systems can’t, be they third-party plugins or rules and filters that you set up within your inbox. They can function as your email triage system, conduct your daily inbox reviews, or even reply to individual messages. The most effective setup combines human support a smart set of email rules and filters—so that you’re not wasting your assistant’s time on the routine job of deleting junk mail or filing missives that you don’t need. Considering how much of your workload likely involves reviewing incoming messages, replying to calendar requests and ensuring your top-priority emails get answered promptly, asking for assistance with email triage is in fact one of the best uses of administrative support.

The decision to delegate

If the idea of delegating email management fills you with alarm, know that you don’t need to give someone full access to your email in order to get meaningful help managing your inbox (more on this in the setup section below). How much of your email you delegate depends not only on how much support you have available, but also on your working style, your relationship with your assistant, and your office culture. Here are few questions to ask yourself before deciding how much email management you can delegate, and whom you want to hire for that support:

How much skill and discretion can you expect? In the most ideal situation, you’d get daily support from a highly trusted assistant who has direct access to your inbox and outbox, so they could work through calendar invitations, billing or financial admin, or other routine requests. But trusting someone with your outbox is only advisable if you trust that person’s judgment about your work and priorities, and know that their grammar and spelling is at least as good as your own. And trusting someone with direct access to the whole of your primary inbox is only advisable if you can expect that person to exercise as much discretion as you’d get from a priest or therapist. If you’re working with part-time or virtual support, you’ll need to scale back these expectations; it will be your job to decide which emails your assistant sees and addresses, rather than vice versa.

What kind of relationship do you have with this person? If you rely on a certain amount of professional distance to make your working relationship successful, it may feel awkward for your assistant to come across personal email from friends or family. If your assistant is paid by your company, rather than you personally, take care to avoid exposing your assistant to messages that could create any conflicts of interest (for example, correspondence about a possible job change). And if you share your assistant with others, think carefully about whether managing your email is feasible in the context of your assistant’s overall workload.

What’s normal in your office? If your peers get help managing their email, or there’s a common practice of delegating certain kinds of email management (like calendaring), then don’t hesitate to do the same. If you would be the first person at your level to get email triage assistance, talk with your manager, HR team, or IT department (to ensure you’re complying with email security guidelines) before asking your assistant to help. And if you’re thinking of hiring an outside assistant on your own nickel, make sure that you only forward or share email in a way that complies with your company’s email policies.

Setting up delegation

Once you have determined who will provide you with email support and to what degree you will rely on them, you need to set up a system that will allow you to manage your inbox collaboratively. That system includes both the technical set-up that will let you share email, and establishing clear expectations about how you and your assistant will work together. I recommend:

Using delegation services: Since sharing your password is a risky proposition, it’s a good idea to share access to your email by using a delegation service like those provided by Gmail or Outlook. Delegation allows someone else to access your email using their own password; you can revoke that access at any time. Outlook even allows you to customize your delegation setup to limit which items your assistant can view.

Creating a second email address: If you’re concerned about providing an assistant with direct access to your email, creating a second email address can be a useful strategy. This can work in one of two ways, depending on how much of your email you want your assistant to handle. If you’d like your assistant to see virtually all your email, provide her with access to your primary inbox, and create a separate email address that you share with people who need to be able to communicate with you on a confidential basis. (You can also use that second email address when you’re on vacation: ask your assistant to forward only those emails you must see, and enjoy the peace of ignoring your main email address.) If, on the other hand, you want your assistant to only handle selected correspondence, set up an address you can forward incoming mail to (possibly via mail rules) and give your assistant access to that address instead.

Specifying your reply protocol: Agree on whether your assistant will reply to emails as you, or by forwarding your emails to an account in his own name, and replying from there (“Sarah forwarded your email, and asked me to find a time for you to meet”).

Drafting sample replies: Particularly if you have a new assistant, or are trying to delegate email for the first time, write a few sample replies your assistant can use as the basis for her own messages. This is especially important if you are authorizing your assistant to send messages as you. While you’re at it, create a few standard replies that you can use yourself whenever you’re forwarding an email to your assistant (“My assistant Jim Smith, cc’ed on this email, can get back to you with a meeting time.”).

Making the most of delegation

Once you have your delegation system in place, there are a few practices and tools that facilitate collaborative email management:

Timing: Agree on when and how often your assistant will review your inbox. If you have access to daily support, your assistant can review your messages first thing, and perhaps at a couple of other agreed-upon times during the day; you’ll look at your inbox after your assistant has moved all extraneous messages into a folder (or folders) that he will work through himself. If your assistant is only providing a few hours of support each week, forward him the messages you’d like him to handle, or put them in a designated folder — just be sure to also reply to your correspondents, letting them know you or your assistant will get back to them in a few days.

Flags and tags: If your assistant has direct access to your inbox, ask her to flag every email in your inbox that you should personally read or address, or conversely, tell her that you will flag any email you want her to handle. This will work best if you are using a system of mail folders, labels or tags to file emails of different types: set up a category or label (“Assistant”) that you can apply to any message your assistant should address, and one (“ReadThis”) for any message you need to read yourself, and make sure you each apply those labels as needed when either of you go through the inbox.

Forwarding: Set up mail rules that forward specific kinds of messages to your assistant, such as meeting requests or invoices. You can also set up a rule that forwards any flagged/starred message, or any message with a specific label; that way you can quickly tag any message you want forwarded, without having to manually forward each one.

Filter-proofing: If you’ve been reluctant to set up rules that move messages out of your inbox before you see them, an assistant can provide a safety net in case things go astray. Just ask your assistant to regularly review all your unread mail (for example, by looking in Gmail’s “all mail” folder, or doing an Outlook search for all unread mail) so that if an important message gets caught by your mail filters, he can move it back into your inbox.

While I came up with most of these tactics at a time when I had a wonderful full-time assistant, they are still useful to me even though now I have only occasional, part-time help. When I hire or task someone to help me on a major project, I often include email support as part of their mandate — and use tactics like selectively forwarding email, or delegating my helper to reply on my behalf.

The biggest challenge in getting email support is making the mental shift away from thinking of email as an area of responsibility that is yours and yours alone. Email is an enormous part of the workload for most professionals. Get help with this area of responsibility, and you’ll not only find it easier to stay on top of email — you’ll find it easier to stay on top of all your work.

The Content Marketing Revolution

We are, at present, in the midst of a historic transformation for brands and companies everywhere — and it centers on content.

Nine out of ten organizations are now marketing with content – that is, going beyond the traditional sales pitches and instead enhancing brands by publishing (or passing along) relevant information, ideas, and entertainment that customers will value. The success of content marketing has radicalized the way companies communicate. For innovative brands, an award-winning Tumblr now carries serious clout; hashtag campaigns have become as compelling as taglines; and the Digiday Awards are as coveted as the Stevies. The content marketing revolution signals more than a mere marketing fad. It marks an important new chapter in the history of business communications: the era of corporate enlightenment.

The phenomenon of content marketing and brand publishing has unfolded rapidly because it responds to consumer preference. According to the Content Marketing Institute, 70% of people would rather learn about a company via an article than an ad. Even The New York Times admits that native advertisements can perform as well as the paper’s own news content. Brand publishing allows companies to react in real time, provide increased transparency, and create a strong brand identity at a fraction of the price of traditional marketing tactics, and in less time.

Yet where brand publishing has had the most profound impact is in empowering organizations to create, facilitate, and leverage the ownership of ideas. That’s largely because great sponsored content is born from a company’s exchange of proprietary knowledge.

When it’s done right, brand publishing encourages companies to mine internal resources and expertise in order to become intellectual agents. Today, large corporations are becoming their own media companies, news bureaus, research universities, and social networks.

The rise of in-house broadcast further illustrates this. Big brands are poaching top-talent journalists in droves and implementing the most successful aspects of the traditional media house. Former journalist Hamish McKenzie is now lead writer at Tesla, USA Today’s Michelle Kessler is now Editor-in-Chief at Qualcomm Spark, and Andreessen Horowitz lured Michael Copeland from Wired. Why? Because trained journalists and writers are in the best position to synthesize information, capture a reader’s attention, and uphold a critical editorial standard. That means establishing an organizational complex that pairs great writers with better editors and incorporates a discerning chain of command, with a managing editor at the helm.

Yet, it would be misguided to assume that corporations are simply transplanting the traditional newsroom. Branded content is a brave new world and a brand’s editorial team, regardless of how it’s organized, must learn to live and breathe a company’s bottom line while also being mindful of the kinds of stories that appeal to readers. The editorial organization within a corporation has to be independent enough to form unique perspectives, but embedded enough to access exclusive information.

This kind of commitment to storytelling and editorial integrity, albeit shaped by sponsorship, is undoubtedly how content marketing has begun to encroach on the whole of marketing. Content, it seems, has miraculously given brands a greater purpose.

Brands are no longer merely peddling products; they’re producing, unearthing, and distributing information. And because they do, the corporation becomes not just economically important to society, but intellectually essential as well.

One of our most innovative clients, General Electric, is a pioneer in content marketing because the company is unafraid to transform internal knowledge about various subjects, from aircraft mechanics to wind turbines, into headline-worthy articles, viral GIFs, corporate microsites, and Tumblr followers. The result marks an evolution for the brand from a company that makes things to a company that produces ideas. Through content, GE establishes itself as a brand in possession of constant newsworthy knowledge.

Red Bull is proof of the extraordinary results great brand publishing can bring. The company’s top-notch content resulted in the creation of an in-house content production arm, Red Bull Media House. Red Bull crafts content that isn’t just compelling, but lucrative in its own right, launching an entirely new ideas-based business for the beverage company.

Unexpected brands like Equinox and Shutterstock use exclusive insight to give audiences useful and actionable content. Equinox’s Q taps into the luxury gym’s network for nutritional recipes, hotel room workouts, and fitness tips from personal trainers—no membership required. Shutterstock’s website presents a tour de force of art, graphic design, and technology that is in parts entertaining, educational, informative, and cultured. That it’s sponsored is an important afterthought—audiences will return to their site for the information, whether they buy stock images or not. Herein is the opportunity: via content, companies can evolve beyond the sum of their products.

Content, when it aligns with exemplary brand publishers of our time, gives companies a new opportunity that didn’t necessarily exist in the last century. Conventional wisdom told brands to keep knowledge quiet, to put “trade secrets” under indefinite embargo and to let exclusive information gather dust in corporate archives. But with the advent of the Internet, social media, and the dispersal of knowledge in every direction, corporations are in the unique position to distribute the information they’ve gathered in exchange for audiences, readership, and brand loyalty.

The Age of Reason in the 17th century was defined by the promotion of ideas and intellect. Considered a revolution of human thought, the Enlightenment bore world-changing advances in the form of ideas, discovery, and invention. Like the philosophers and scientists who populated the salons of that era, corporations today can and should participate in the dynamic exchange of innovative ideas, unique knowledge, and expertise.

Of course, not all brands can—or should—be expected to cover scientific breakthroughs or economic theory, but every brand can do better than a contrived content marketing strategy. Ninety percent of B2C marketers use content in their strategy, but few brands recognize the real opportunity in doing so.

Content can be the means by which a brand shapes and impacts business and consumer landscapes; it can be a thoughtful investment in a company’s legacy. Armed with quality content, corporations can become thought leaders, change agents, and experts. They can, in fact, become enlightened.

The New Marketing Organization

An HBR Insight Center

How Sephora Reorganized to Become a More Digital Brand

CMOs and CEOs Can Work Better Together

Marketers Need to Think More Like Publishers

Brands Aren’t Dead, But Traditional Branding Tools Are Dying

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers