Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1404

June 25, 2014

Marketers Don’t Need to Be More Creative

Marketers worldwide grew up with John Wanamaker’s famous marketing aphorism, “Half of my advertising is wasted; I just don’t know which half.” That pithy quote is now a misleading anachronism; we can know which half. Digital media and tracking technologies, along with dramatically improved analytics, now mean that serious marketers — if they really care to know — can have an excellent idea of just how effective (or wasteful) their advertising really is. Ignorance is now a choice, not an excuse.

This new reality has sparked global Game of Thrones-like hostility and rivalry in the marketing and advertising communities. Traditional “creatives” and disruptive “technologists” are locked in global conflict for bigger budgets and influence. “Ad Creativity Takes Back Seat to Tech at Cannes,” The Wall Street Journal recently declared. At the advertising industry’s most prestigious, sybaritic, self-indulgent, and self-awards gathering, the “Mad Men” are losing to the nerds, quants, and geeks. Couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch.

“In the last five years the industry has changed more than in the last 25. It’s created chaos,” Unilever Chief Marketing Officer Keith Weed told Cannes attendees. “What’s changed so radically is we’re no longer just competing with the geniuses that create content in places like Hollywood, we’re competing against everyone.”

“The question is,” said Miles Young, CEO of WPP subsidiary Ogilvy & Mather, “can there be enough focus on creativity?”

Unfortunately, that’s the wrong question. If there’s anything all that chaos and competition of the past five years should have taught agencies, it’s that too much “creativity” celebrated by marketers and advertisers really isn’t. Advertising creativity has long been a bit of a con job; the media world is filled with costly creative that neither builds brands nor sells products. The better argument is that traditional advertising and marketing firms have pathologically overinvested in creativity while consistently underinvesting in meaningful metrics. An even better case might be made that the multimedia successes of Google, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, Facebook, and so on, highlight just how flaccid and ineffective most creative advertising and market work has been. What’s the secret sauce these technologies all have in common? Their creativity is measurable, trackable, and accountable. That’s a winning combination. If you’re a brand manager or CMO, that’s what you should care about.

The ongoing revolution that “may reflect angst felt on the creative side of the industry as digital technology changes consumer behavior and complicates the ad world” (as The Journal put it) is less about creativity than the future of accountability. Smart advertisers don’t privilege good creativity over good metrics. Metrics let you learn in ways that creativity does not. The ability to see who takes an in-store selfie or tweets a product complaint confers power and insight. New media should inspire new metrics. New metrics should create new accountability. New accountability should provoke and promote new kinds of creativity.

When marketing metrics were crude, vulgar, and Wanamakerian, creativity was more important because, frankly, it at least offered the appearance and illusion of effectiveness and control. Creatives could both figuratively and literally “own” the brand story. But in an era where machine-learning algorithms can sync clicks, pupil dilation, tweets, likes, recommendation engines, and home delivery services, creativity becomes less a focal point than a measurable means to a business end. True creative genius may transcend metrics. But anyone regularly exposed to advertising or marketing campaigns knows first-hand that even brilliance, let alone genius, is in shockingly rare supply. That’s why marketers, advertisers, and brand leaders are wiser to invest in monitoring, measurement, and analytics. Whirlwind romance shouldn’t excuse limp underperformance.

Marketing creativity — and creative marketing — should no longer escape, elude, or fake accountability. That nervousness and discomfort manifesting in the suites and sands of Cannes are symptomatic of an elite that will quite literally be held to account for the measurable impact of their creative work. If that “creative” campaign doesn’t move the needle of a net promoter score, then what was creativity’s point? To win an award at Cannes, perhaps?

No, the essential question serious and strategic marketers and advertisers should ask isn’t, “How can we make ourselves more creative?”; it’s “How can we make ourselves more accountable?” Technology should be seen less as a medium of creative expression than a platform for assessing how well people engage with and get value from our products and services.

Greater accountability enables and invents greater creativity; greater creativity, alas, doesn’t invent or inspire greater accountability. Yesterday’s CMOs still cling to Don Draperian hopes of creativity with minimal accountability; tomorrow’s CMOs understand that accountability will make authentic creativity even more valuable.

The New Marketing Organization

An HBR Insight Center

Your Marketing Organization Needs an Overhaul

CMOs and CEOs Can Work Better Together

Marketers Need to Think More Like Publishers

Brands Aren’t Dead, But Traditional Branding Tools Are Dying

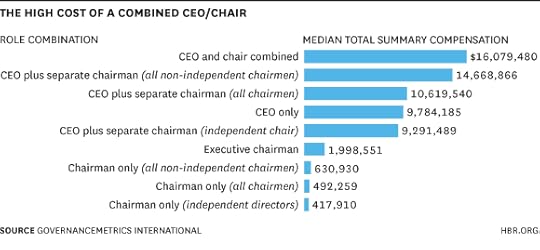

The Cost of Combining the CEO and Chairman Roles

Will Netflix’s shareholders be sorry that they voted to let Reed Hastings carry on as both CEO and chairman? A look through the research on combining and separating out the two roles suggests that, much like most splits in life, the answer is… complicated.

Netflix’s shareholders notwithstanding, most people assume the right answer is to keep the two roles separate, in the interests of diversity of thinking and proper CEO oversight. And that’s how pretty much every research report starts — before going on to explain why it probably isn’t so.

Back in 2006, for instance, in an article in our magazine entitled “Before You Split that CEO/Chair…,” Robert Pozen, chairman (but not CEO) of a Boston-based investment management firm, cited three studies from three different countries (the U.S., the U.K., and Switzerland) which each found no statistically significant difference in terms of stock price or accounting income between companies that split the roles and those that combined them. These findings echoed dozens of previous ones going as far back as 1996.

Yet over the same period, a steady stream of business thinkers and practitioners offered up reasons (if not data) for why splitting the two roles could cause trouble. In 2003, for instance, in “In Defense of the CEO Chair,”Harvard Law’s William Allen and William Berkeley (who was chairman and CEO of the eponymous insurance holding company) argued that doing so would create two armed camps that would interfere with productivity. Two years later, Jay W. Lorsch and Andy Zelleke similarly argued in the Sloan Management Review that splitting the two roles blurs lines of responsibility, distracts both parties, and creates power struggles.

Maybe that’s why the 2012 research from Matthew Semadeni and Ryan Krause at the University of Indiana’s Kelley School was so widely reported as suggesting that the roles should not be split unless the company is doing badly. But a closer look shows the findings have more in common with the “it doesn’t make any difference” camp than the headlines would suggest.

The study looked at three scenarios, all of which involved what happens when a combined CEO/chair is split. In the first, a sitting CEO/chair gives up the CEO role but remains chairman, essentially making the incoming CEO an apprentice. In the second, the incumbent CEO/chair leaves (voluntarily or not), and the positions are filled with two separate people. In the third, a CEO/chair remains CEO but gives up the chair to another (what the researchers referred to as a demotion). In that last circumstance, if the company was in difficulties, the data indicated that splitting the two roles, so that someone could ride herd over a less-than-ideal CEO, made a positive difference. But in the first two cases, once again, the data found no difference in company fortunes. From this, Krause drew a general if-ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it conclusion, not because splitting the roles would cause harm but because when a company is doing well, it doesn’t appear to matter which model you follow.

That same year, though, a more obscure study from GovernanceMetrics International, highlighted by the Harvard Law School Forum, approached the question from a different angle, tracking not just the effects but the costs of splitting the two roles.

The 2012 study looked at 180 North American corporations with a market capitalization of $20 billion or more. Given the complexities of running such large businesses, it was thought, differences in cost and performance of different leadership structures would be especially marked.

And differences there were. Surprisingly, combining the two roles cost more than splitting them – much more. Median total compensation (base salary, bonus, incentives, perks, stock, stock options, and retirement benefits) of executives holding both positions was $16 million. That was nearly 60% more than the median combined compensation ($10.6 million) awarded to the two individuals in companies in which the positions were split. Considering that median income for the chair-only position was just under $500,000, it’s hard not to avoid drawing the conclusion that the order-of-magnitude $5.4 million extra the CEO receives for taking on the additional chairmanship duties is rather a lot. This impression is further strengthened by the fact that the median income for non-independent chairs was $630,930 — more than 50% higher than the $417,910 for independent chairs (making a company run by a separate CEO and independent chair a real bargain).

One might argue that differences in compensation reflect differences in corporate performance, and if that’s the case, it would be a strong argument for combining the two roles. That was so in this study – but only in the short term. Median one-year shareholder returns for companies in which the roles are combined were an impressive 11.65%, compared with a distinctly anemic 2.27% for those in which the roles were separate. Over time, however, performance for the first group lagged and the other improved such that shareholders shelling out for a combined CEO/chair received five-year returns of 31.3% while their counterparts, paying considerably less to both their CEO and chair, were enjoying an even more impressive 39.96% return.

Put all of these finding together, and perhaps the only conclusion one can draw is that the higher long-term returns for companies in which the roles are separate come from struggling companies that take steps to address the inadequacies of their CEOs (or that lower returns in companies where the roles are combined come from allowing a poor CEO too much latitude for too long).

Otherwise, most of the research suggests that Netflix’s fortunes, like most companies, will be what they will be – regardless of whichever governance system the shareholders vote in.

For PGA Players, Driving Now Beats Putting as the Most Lucrative Skill

As golf courses used by the Professional Golfers’ Association have changed in recent years—with the fairways getting longer, the grass height in the rough being cut shorter, and the cups being shifted to locations that are harder to reach—driving has replaced putting as the professional golfer’s top money-making skill, according to a study by Carson D. Baugher and Jonathan P. Day of Western Illinois University and Elvin W. Burford Jr. of Junior’s Shaft Shack in Forest, Virginia. Previous studies showed that putting was a player’s most lucrative capability, but drawing on recent PGA Tour data, the researchers found that a 1-standard-deviation increase in driving distance would have boosted a player’s earnings by an average of $671,779.15 in 2013, whereas the same relative increase in putting skills would have raised his earnings by just $510,195.91. Iron, chipping, and sand skills remain significantly less important than driving and putting.

June 23, 2014

For Breakthrough Innovation, Focus on Possibility, Not Profitability

More than 15 years after its founding, Google remains a company that inspires profound admiration — and at times, a bit of confusion.

The company is currently investing in self-driving cars, a futuristic idea that some people believe will never be achieved. It’s also rolling out Google Glass, a wearable computing device that’s inspired skepticism and some mockery.

The derision is misplaced. As someone who’s been involved in marketing breakthrough innovations, I’m convinced Google’s approach is the right one. Google is focused on possibility rather than profitability — a mindset that’s necessary to create innovations that transform categories. Many breakthrough innovations I’ve led have suffered when I’ve let the profitability mindset creep in. Google should be admired for first setting out to answer the question: “Is this possible?”

Successful innovations programs create a balance between the probable/profitable short-term programs and the possibility programs that challenge the status quo. Unfortunately, most companies are organized and focused on the probable/profitable short term, and therefore miss the potential of breakthrough innovation that comes from being focused on the possible. This is frequently how well-established category leaders miss opportunities that transform their categories.

Programs that transform take patience. Speed to market, probability of quick return, and profitability mindset have to take a backseat to truly delivering a product that delights the consumer in every aspect. My perspective on this comes from my own experience.

At Keurig, the pod-based coffee company where I worked as president for six years, sales grew at a 61% compound annual rate, propelling Keurig Green Mountain from $500 million to $4.5 billion in net sales from 2008-2013. Keurig machines sit on the counter in more than 18 million households. Most people think that Keurig just recently appeared. But in fact, Keurig was founded more than 15 years ago. The first machines were sold in 2000.

Today, The brewers cost $100 or $150, still a significant premium to the standard drip coffee maker. But what many people forget is that in its early years, Keurig brewers cost $900 apiece. Early K-cups were made by hand. Keurig opted to start out in the office coffee market, not the consumer market. That made the $900 price point competitive and acceptable. The whole approach to the office became a way to commercialize the design quicker and to gain consumer experience as the company drove the brewer down the cost curve. The wider diversity of coffee drinkers in an office (vs. a single consumer household) planted the seeds of the importance of having an eco-system of brands beyond our own. This led to the variety and partnering strategy that has been at the core of Keurig’s success. Today, Starbucks, Dunkin Donuts, Folgers, Caribou, Peets, and Snapple, to name just a few, participate as partners in the system. It’s the only brand of single serve that offers a wide variety of brands of coffee and roasts, along with other beverages.

If the company’s founders and early leaders had focused on profitability instead of possibility, I’m not sure the system would have been as successful. And they certainly wouldn’t have invited the competition to share in the system to maximize the variety. Variety accelerated the growth. It was the vision of transforming the way consumers make coffee that took them on the decade long journey to success, growth and profitability.

Possibility sharply focuses the scope of the breakthrough innovation. If the only question is “Is it possible to make it?”, then that question defines who you bring onto the team both from a capability standpoint (can this person help us figure it out?) and from a character standpoint. (Specifically: Does this person bring an optimistic or pessimistic perspective?) People who make great leaders of breakthrough innovation programs always ask the “What if” question. It frees you to look for talent and resources beyond your company — who are the partners who will share your vision, who bring incremental talent and cross-category perspectives to make this work?

One of the key ingredients to the possibility mindset is the addition of truly understanding what the consumer wants. The question isn’t just “Is it possible to make it?” but “Is it possible to make exactly what your specific target consumer wants?” In contrast, the profitability mindset shuts down ideas and shortcuts the process. It stifles creativity and likely limits the team to only those ideas, capabilities, business models, and resources already inside the company.

Once the original ‘is it possible’ question has been solved for, the trick is to apply the same optimistic, focused thinking to the commercialization process. Now that we know it is possible to make, is it possible to make smaller, faster, better, and more cost effectively?

The opportunity is to create a win-win: Create something that is right for the consumer and by doing this, transform a category and create a long term sustainable growth opportunity for the company.

Google is looking at “possiblity’ with Glass and self-driving cars. Both may seem like strange or silly innovations today, but over time they could turn into true breakthroughs and gain wide acceptance.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

Customer Complaints Are a Lousy Source of Start-Up Ideas

Disarming Landmines Through Strategic Innovation

The Innovation Strategy Big Companies Should Pursue

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

Few Consumers Actually Heed Social Media

Ever since Facebook first introduced brand pages in 2007, companies have been flocking to social media. Many business leaders believe that the more they post and share about their products and services, the greater their chances of attracting customers and generating revenue.

But just-released research from Gallup’s State of the American Consumer report suggests that much of these efforts have been misguided.

Social media are not the powerful and persuasive marketing force many companies assumed they would be. Gallup finds that a full 62% of U.S. adults who use social media say that these sites have absolutely no influence on their purchasing decisions. Another 30% say these sites have some influence, and just 5% say they have a great deal of influence.

And although companies may think that people who “like” or follow them on social media are an attentive audience, our research suggests otherwise. Of consumers who report liking or following a company, 34% still say that social media have no influence on their purchasing behavior, while 53% say they have only some influence.

When compared with more traditional forms of social networking, social media initiatives may actually be the least effective method for influencing consumers’ buying decisions. Gallup research has shown that consumers are much more likely to turn to friends, family members, and experts when seeking advice about companies, brands, products, or services. Social media sites have almost no sway.

These findings raise a question: is there an inherent flaw in the idea of using social media to drive purchasing, or have companies just been using social media poorly? The fact that some portion of buyers credit social media with having real influence suggests the latter may be true. Consumers are drawn to social media because they want to take part in the conversation and make connections. But many companies continue to treat social media as a one-way communication vehicle and are largely focused on how they can use these sites to push their marketing agendas.

To positively influence purchasing through social media, marketers should learn to use it to listen and interact. Consumers are more likely to engage when the brand-related posts they encounter are:

Authentic. Social media sites are highly personal and conversational. And, as Gallup finds, consumers who use these sites don’t want to hear a sales pitch. They’re more likely to listen and respond to companies that seem genuine and personable. Companies should back away from the hard sell and focus on creating more of an open dialogue with consumers.

Responsive. The social media world is 24/7, and consumers expect timely responses – even on nights and weekends. Companies must be available to answer questions and reply to complaints and criticisms; ignoring negative feedback can do considerable damage to a brand’s reputation. Instead, companies must actively listen to what their customers are saying and respond accordingly. If they made mistakes, they must own up to them and take responsibility.

Compelling. Content is everywhere, and consumers have the ability to pick and choose what they like. Companies must create compelling, interesting content that appeals to busy, picky social media users. This content should be original to the company and not related to sales or marketing. Consumers need a reason to visit and interact with a company’s social media site and to keep coming back.

When companies focus their social media efforts on pushing product and not cultivating communities, they overlook the real potential of these channels. Gallup research has consistently shown that customers base purchasing decisions on their emotional connections with a brand. Social media are great for making those connections — but only when a brand shifts its focus from communication to conversation.

It’s Time for a New Partnership Between Labor and Management

Lloyd Blankfein recently told a TV audience that income inequality is “very destabilizing” and that “too much of the GDP over the last generation has gone to too few of the people.” When even the CEO of Goldman Sachs is worried about inequality, you know you have a problem.

Rising inequality reflects two trends. One is the rapidly growing incomes of those at the top, a phenomenon publicized by everyone from Occupy Wall Street to Thomas Piketty. The other is the remarkable lack of income growth among the rest of the population. In the three decades after World War II, the income of the lower 90%, meaning the broad middle class as well as the poor, nearly doubled. Since then it has barely budged. Yet overall per-capita income growth in the past 40 years has been nearly as strong as in the postwar era (1.9% a year vs. 2.2%). It’s just that the fruits of this growth went to “too few of the people.”

How can Americans create a society where more people share in the growth? We’d like to see a revived labor movement — but with a new business model.

Suspend disbelief about labor for a moment and look at the facts. In the postwar period, U.S. unions were strong. At their peak they represented nearly one-fourth of private-sector workers. Their influence extended beyond their numbers, since many nonunion employers observed union standards in hopes of avoiding an organizing drive. Labor’s negotiators took productivity gains as their touchstone and bargained for commensurate wage gains. As the economy grew, middle-class income grew with it.

Economic analysis bears out the connection between strong unions and less inequality. Union workers earn 15% to 20% more than similar nonunion workers. CEOs of unionized companies earn 10% to 20% less than their nonunion counterparts. In the public sector, unions remain relatively strong — and have helped prevent the rise in inequality we’ve seen in the private sector. Nearly every developed nation with less inequality than our own has a strong labor movement.

But the business model of private-sector unions is essentially defunct. U.S. unions in the past defined themselves in opposition to management — us vs. them, in the famous labor-movement phrase — rather than as partners in building a successful company. They fought for high wages and restrictive work rules regardless of business conditions. That model worked fine as long as large sectors of the U.S. economy were dominated by a few big firms — the companies could (and did) pass the added costs along to consumers. But it doesn’t work in a global marketplace. As world competition stiffened, some unionized companies moved or went out of business. Others fought labor tooth and nail, ridding themselves of unions whenever they could. As a result, labor sank to its current level: less than 7% of private-sector workers now belong to a union.

What would a better business model for labor look like? Begin with an obvious but often overlooked truth: labor and management don’t have diametrically opposed goals. Both sides want their companies to succeed and grow, creating a bigger pie for everyone. Remember, too, that companies with engaged, committed workforces tend to outperform competitors. Involved employees come up with more innovative ideas, figure out how to solve problems, and go the extra mile for customers.

So imagine a partnership approach. The union says to management, We’re here to make your business more productive and profitable. We’re experts in team-based and participative systems. We have the credibility to get employees really involved in the business, and we know how to do so. Over time, the union label might come to denote a world-class company, one with the skills to do things that competitors can’t.

The union’s message to employees would be similar. We’ll make you more productive and we’ll give you valuable skills — the only path to greater job security and future opportunities. In hard times we’ll help the company find ways to cut costs short of layoffs. In good times we’ll negotiate for a healthy share of profits, stock, or both, as well as for higher wages. That seems like an approach worth an employee’s dues.

No U.S. company has a labor-management relationship exactly like this, but Southwest Airlines comes close. Its unions — which represent 83% of the airline’s workforce — have generally cooperated with management on business improvement initiatives even as they bargained over pay and benefits. A few years ago, for example, jet fuel prices were climbing sharply. The company and the pilots’ union launched a joint program known as Plane Smart Business to get pilots involved in tracking their own fuel usage and coming up with ways to reduce it.

Lloyd Blankfein is right to be worried: if nothing changes, our capitalist system will continue to look more and more like that of the Gilded Age, with the majority of households suffering from stagnating income and a relative handful growing very rich. This level of inequality is bound to become destabilizing, which means we should be thinking now about how to mitigate the trend. Unions played a key role in the past. Maybe they can in the future as well.

Make Customers Want to Buy Offline

Showrooming, once a worry primarily for consumer electronics retailers, is expanding into markets we might have thought exempt. Today we can investigate everything from cars to books to groceries in person and then proceed to order them online, often with greater ease and significant savings.

Chalk this up to the efficiency of digital retailers, who’ve systematically dismantled every obstacle to online shopping. Shipping is fast and cheap, returns are a snap, and customer service is often better than what you find in a store. Price competition these days is a guaranteed losing strategy, especially with Amazon, whose long cash floats and high inventory turnover allow them to stay profitable even with no margin. Stores like Best Buy and Walmart once seemed unstoppable as they displaced independent retailers; now the Goliath has become David.

Yet for each Radio Shack and Barnes and Noble fighting for its life, there are still those beloved corner stores and discount chains that manage to thrive. Many keep a close eye on the prices being charged by their digital competitors, and work to keep theirs from straying too much higher. Most learn to emphasize their advantage in immediacy. More than anything, these successful brick-and-mortar stores know to compete on experience.

A satisfying real-life retail experience is something Amazon can never duplicate – but the trick is translating that satisfaction into dollars spent on-site. We should see this as an experience design problem. A look at retailers who succeed despite showrooming reveals three design imperatives.

Design for empathic expertise. When a shopper uses a physical retail setting as a showroom, what are they looking for? A better look at the merchandise, and the benefits of touch and feel – but even more, for expertise that could guide their choice. You probably have a business you patronize for exactly this reason, whether it’s the boutique that knows what’s on trend, or the specialty grocer who can advise on preparation of a dish, or the wine seller who can recommend the right bottle to go with that meal. Backcountry.com and Zappos, for example, are excellent online retailers, but they haven’t displaced REI or the local shoe store, because people value that hands-on expertise. Especially when the purchase is something we really care about, we’re willing to pay extra for a trusted advisor helping us make the right choice.

How could the shopping experience be designed to emphasize your expertise – and get it paid for? The challenge begins with improving staff hiring and training. Good people also need good information. If you can create a data system to give employees quick access to information about products and customers, you can equip them to advise as experts. Conversely, if shoppers perceive that the kid behind the counter knows little more than they do – or worse, has an incentive other than the consumer’s interests to steer them toward certain choices – they will have no qualms about leaving the store and buying online. Design your retail setting to be a showroom for your empathic experts even more than for the products you sell.

Design for whole solution provision. When you buy a new computer, you may also need new peripherals and software to accomplish what you’re hoping to do with it. A new bike often means a new helmet, lock, and lights. A new coat calls for a matching scarf and gloves. Especially in the consumer electronics category, where technologies shift with blinding speed, customers are often happy to take care of these purchases all at once, in person, even if it means spending a few dollars more. Concerns about compatibility are certainly part of it (how do you choose wisely if you can’t tell USB from HDMI, or a Schrader valve from a Presta?), but so are perceptions of price. Spending an extra five or ten dollars seems reasonable when investing in a solution that costs hundreds or thousands. The desire to assemble a combination that works, right away, can derail an obsession with paying the lowest price.

For retailers, this has implications not just for the expertise you need in problem solving, but also for the products you stock and how they are displayed. The extras here are very different from the impulse buys we make while waiting in the supermarket checkout line. They’re considered purchases that weigh current and future needs against budget, and must respect the requirements of the central product they work with. They can also add up to hundreds of dollars.

This means designing your store to serve as a source for solutions, both now and in the future. Again, heightening your staff’s expertise helps immensely. So does offering customers a complete ecosystem of secondary products, rather than simply hanging some earbuds and cases within easy reach. Design with an eye to the outcome the customer is seeking, whether that’s more reliable transportation, more exciting entertainment, or higher productivity. Deliver a system of products and services that works with their primary purchase to provide those outcomes, and they’ll reward you for it, rather than try to reconstruct it all for themselves online.

Design for community. Portland, Oregon, where Ziba has its headquarters, is so saturated with bike-oriented businesses that when a newcomer, Velo Cult, announced in 2012 it was moving its bicycle repair shop here from San Diego, observers wondered loudly whether it had any chance of success. It didn’t help that even the local mainstays were being challenged by online competitors discounting the products they sold at retail.

Rather than compete on price or selection, though, Velo Cult works “to be equal parts bike shop, venue, and bar” – in other words, a community. The large space they occupy is open plan, with long tables and benches, repair stations along one side, and a beer and coffee bar along the other. They offer the space up to local organizations for seminars, meetings, and parties, whether bike-related or not. Within months, Velo Cult became a de facto community center for many of the city’s two-wheeled enthusiasts. It also became a profitable business.

It’s an unusual model, but a great design solution in a saturated market. Any shop can sell you a rack or floor pump, or tune up your road bike; for consumers, the decision of where to shop (online or off) comes down to convenience and trust. By establishing itself as a community hub, Velo Cult showed thousands of potential customers that it was easy to get to, pleasant to visit, and aligned with their own values. If you visit a store three times to attend an event or grab a drink, your fourth visit could be to buy a new pair of tires…even if you could’ve ordered them from Amazon for a few dollars less.

Not every retail environment can be a community center, of course, but the demand for such spaces is huge and unmet, and there are endless ways to build community — even in surprising environments, like financial institutions. Since its “Slow Banking” redesign in 2003, Oregon-based Umpqua Bank has provided ample seating, free coffee, and wifi to its customers, and offered up its branches for meetings, workshops, and concerts. In that time, it’s grown from less than 70 branches to nearly 400, becoming the largest regional bank in the Western US.

Both Umpqua and Velo Cult succeeded by orienting their spaces around community first, and sales second. Companies looking to emulate their success should realize that the visual differences are relatively small, but policy shifts can be fundamental, from encouraging events that generate little or no revenue, to changing the way employees are incentivized and trained.

One fundamental point deserves to be underscored, because it informs all three of these design imperatives: shopping is emotional. The internet offers many functional advantages: selection is endless and endlessly searchable, prices are excellent, and there’s none of the hassle of going to the store. Most purchases, though, aren’t purely functional, and a well-designed shopping experience works with that by heightening the positive emotions and countering the negative ones.

More than just satisfying emotional needs, shopping is part of how we form identity. The decisions we make about how we will spend our money are part of how we present ourselves to the world. Offer customers an experience that deepens their sense of identity and reflects positively on it, and you’ll earn the higher margin you’re asking them to pay.

How to Help an Underperformer

As a manager, you can’t accept underperformance. It’s frustrating, time-consuming, and it can demoralize the other people on your team. But what do you do about an employee who isn’t performing up to snuff? How do you help turn around the problematic behavior? And how long do you let it go on before you cut your losses?

What the Experts Say

Your company may have a prescribed way of handling an underperformer, but most of those recommended processes aren’t that useful, says Jean-François Manzoni, a professor of management at INSEAD and coauthor of The Set-Up-to-Fail Syndrome: How Good Managers Cause Great People to Fail. “When you talk to senior executives, they’ll usually acknowledge that those don’t work,” he says. So chances are, it’s up to you as the manager to figure out what to do. “When people encounter an issue with underperformance, they really are on their own,” says Joseph Weintraub, a professor of management and organizational behavior at Babson College and coauthor of the book, The Coaching Manager: Developing Top Talent in Business. Here’s how to stage a productive intervention.

Don’t ignore the problem

Too often these issues go unaddressed. “Most performance problems aren’t dealt with directly,” says Weintraub. “More often, instead of taking action, the manager will transfer the person somewhere else or let him stay put without doing anything.” This is the wrong approach. Never allow underperformance to fester on your team. It’s rare that these situations resolve themselves. It’ll just get worse. You’ll become more and more irritated and that’s going to show and make the person uncomfortable,” says Manzoni. If you have an issue, take steps toward solving it as soon as possible.

Consider what’s causing the problem

Is the person a poor fit for the job? Does she lack the necessary skills? Or is she just misunderstanding expectations? There is very often a mismatch between what managers and employees think is important when it comes to performance, Weintraub explains. It’s critical to consider the role you might be playing in the problem. “You may have contributed to the negative situation,” says Manzoni. “After all, it’s rare that it’s all the subordinate’s fault just as it’s rare that it’s all the boss’s.” Don’t focus exclusively on what the underperformer needs to do to remedy the situation — think about what changes you can make as well.

Ask others what you might be missing

Before you act, make sure to look at the problem objectively. You might talk to the person’s previous boss or someone who’s worked with him, or conduct a 360 review. When approaching other people, though, do it carefully and confidentially. Manzoni suggests you might say something like: “I’m worried that my frustration may be clouding my judgment. All I can see are the mistakes he’s making. I want to make an honest effort to see what I’m missing.” Look for evidence that might prove your assumptions wrong.

Talk to the underperformer

Once you’ve checked in with others, talk to the employee directly. Explain exactly what you’re observing, how the team’s work is affected, and make clear that you want to help. Manzoni suggests the conversation go something like this: “I’m seeing issues with your performance. I believe that you can do better and I know that I may be contributing to the problem. So how do we get out of this? How do we improve?” It’s important to engage the person in brainstorming solutions. “Ask them to come up with ideas,” says Weintraub. Don’t expect an immediate response though. The person may need time to digest your feedback and come back later with some proposals.

Confirm whether the person is coachable

You can’t coach someone who doesn’t agree that they need help. In the initial conversation — and throughout the intervention — it’s critical that the employee acknowledge the problem. “If someone says, ‘I am who I am’ or implies that they’re not going to change, then you’ve got to make a decision whether you can live with the issue and at what cost,” says Weintraub. On the other hand, if you see a willingness to change and a genuine interest in improving, chances are you can work together to turn things around.

Make a plan

Create a concrete plan for what both you and the employee are going to do differently, agreeing on measurable actions so you can mark progress. You should also ask what resources the employee needs to accomplish those goals. You don’t want her to make promises she can’t meet. Then, give her time. “Everyone needs time to change and maybe learn or acquire new skills,” says Weintraub.

Regularly monitor their progress

It may seem obvious, but unfortunately, many managers fail to follow up. Ask the person to check in with you regularly, or set up a time and date in the future to check progress. It may be helpful to ask the employee if he has someone that he’d like you to enlist in the effort. Weintraub suggests you ask: “Is there anyone you trust who can provide me with feedback about how well you’re doing in making these changes?” Doing this sends a positive message: “It says I want this to work and I want you to feel comfortable; I’m not going to sneak around your back.”

Respect confidentiality

Along the way, it’s important to keep what’s happening confidential — while also letting others know you’re working on the underperformance problem. Manzoni admits that this is a tricky line to tow. Don’t discuss the specific details with others, he says. But you might tell them something like: “Bill and I are working together on his output and lately we’ve had good discussions. I need your help in being as positive and supportive as you can.”

If there isn’t improvement, take action

If things don’t get better, change the tenor of the discussion. “At some point you leave coaching and get into the consequences speech. You might say, ‘Let me be very clear that this is the third time this has happened and since your behavior hasn’t changed, I need to explain the consequences,’” says Weintraub. Disciplinary actions, particularly letting someone go, shouldn’t be taken lightly. “When you fire somebody, it not only affects that person, but also you, the firm, and everybody around you,” says Manzoni.

While it may be painful to fire someone, it may be the best option for your team. “It’s disheartening if you see the person next to you not performing,” says Weintraub. Manzoni elaborates: “The person you’re asking to leave is only one of the stakeholders. The people left behind are the more important ones . . . When people feel the process is fair, they’re willing to accept a negative outcome.”

Praise and reward positive change

Of course if the person makes positive changes, say so. Make clear that you’re noticing the developments and reward him accordingly. “At some point, if the non-performer has improved, be sure to take them off the death spiral. You want a team that can make mistakes and learn from them,” says Weintraub.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Take action as soon as possible — the sooner you intervene the better

Consider how you might be contributing to the performance issues

Make a concrete, measurable plan for improvement

Don’t:

Forget to follow up — monitor their progress regularly

Waste your time trying to coach someone who is unwilling to admit that there’s an issue

Talk about specific performance issues with others on the team

Case study#1: Be ready to invest time

Allie Rogovin managed a five-person team at Teach for America when she brought in Max* as a recruiting coordinator. The job had two main responsibilities: completing administrative duties that supported the recruiting team and managing special projects. Allie recognized that the administrative component wasn’t that exciting. “So I let him know that the better and faster he completed these tasks, the more time he’d have for the fun projects,” she says. But before long, Max was struggling with the core part of his role. “I realized a couple months into the job he wasn’t getting his administrative duties done in time,” she says.

Allie started by giving Max an action plan template. She asked him to take 20 minutes at the end of each day to enter and prioritize all of his tasks . She then reviewed his list every evening and gave him input on how he might shuffle his priorities for the next day. They also started meeting three times a week instead of just once a week.

“He was a very valuable team member and I knew he could do a good job. That made me want to invest time in working with him,” she says. She continued meeting with Max regularly and reviewing his priorities for three months. “I didn’t think it was going to be that long but I wanted to see that he was building new habits,” says Allie. Max still occasionally missed deadlines but he was showing definite signs of improvement. “We tweaked the plan along the way and he eventually got into the swing of things,” she says.

“I frankly wouldn’t have done it if I didn’t see huge potential in him,” says Allie.

Case study #2: Make clear what needs to change

Bill Wright*, a business developer at a residential building company, hired a new project manager last summer. We’ll call him Jack. Right from the start, Bill saw performance issues. One of Jack’s primary responsibilities was to develop small projects. That meant defining the scope of the project, talking with homeowners, negotiating with subcontractors, and coordinating with design professionals. “He was taking too long to get things done. What should’ve taken days, was taking three to four weeks,” Bill says. This was problematic for many reasons: “I was supposed to be billing his time to the client but I couldn’t bill for the amount of time he was putting in. Plus I had disgruntled homeowners who were wondering why things were taking so long.”

Bill met with Jack weekly to review the current workload, prioritize tasks, and resolve any issues. “I wanted to help him move things forward but eventually I got so frustrated that I started to take projects over,” Bill says. At Jack’s 90-day review, Bill had a frank conversation with his employee about the consequences of not being able to turn around his performance. “When I asked what he needed, Jack said that he wanted more than an hour of my time each week to get more input on his work. I said I was happy to do that and asked him to go ahead and schedule a regular meeting time,” Bill says. But Jack never followed up or put any additional time on Bill’s calendar.

“It was very clear that it wasn’t working out. There were never signs of any progress.” That’s when Bill sat Jack down and made it clear that his job was on the line. Again, there was no change in behavior, so several weeks later, he let Jack go. “I look back on it and realize I made a bad hire. I recently hired his replacement and it’s like night and day. He already gets the job.”

*Not their real names

Do You Really Want to Be Yourself at Work?

Would you love to work in a place where you could truly be yourself? Where you didn’t have to spend a single moment of your time and energy making sure you put only your best self forward?

Most people would, according to research recently published by Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones in “Creating the Best Workplace on Earth.” For three years they went around the world, asking hundreds of executives to describe the attributes of their ideal workplace. Topping the list was an environment where people could be themselves and where the company invested in developing them (and everyone they worked with) to be the very best they could be.

Interestingly, during a comparable three-year period, Harvard education professor Robert Kegan was researching the other side of the equation, looking for companies that pursued competitive advantage by developing every person to his or her fullest potential. He and his colleagues Lisa Lahey, Andy Fleming, Matthew Miller, Claire Lee, and Inna Markus had put out the word among their extended networks in academia, consulting, HR, and corporate C-suites: Did anyone know of any organization, anywhere in the world, dedicated to developing every one of its people by weaving personal growth into day-to-day work?

The researchers found precious few companies that took that approach. In their initial pool of only 20 candidates, just two with 100 or more employees had been operating fully and successfully in that mode for at least five years. One was an East Coast investment firm called Bridgewater Associates, the other a West Coast real estate and movie theater management company called Decurion. The researchers spent hundreds of hours viewing the two firms’ practices and interviewing their people (and wrote about them in detail in “Making Business Personal”).

In these companies employees didn’t spend any time hiding their inadequacies or preserving their reputations. Rather, everyone — from the CEO on down — was expected to make mistakes and learn from them and grow. In fact, both organizations had elaborate systems designed to promote individuals into roles a bit beyond their comfort zones to ensure that they would inevitably learn from failure. In this way people became masters not of any particular skill but of learning to adjust to new situations, which produced organizations that were remarkably resilient.

Does that sound appealing? Before you answer, consider this anecdote, which Kegan also records in his article.

Not long ago, HBS professor Heidi Gardner presented a case she’d cowritten on Bridgewater to her class. “So how many of you would like to work at Bridgewater?” she inquired toward the end of the discussion. Fewer than five hands went up in a class of 80. “Why not?” she asked. One young woman who’d been an active and impressive contributor to the conversation answered: “I want people at work to think I’m better than I am; I don’t want them to see how I really am!”

And yet, how many people would disagree with Ted Mathas, the head of the mutual insurance company New York Life, who told Goffee and Jones: “When I was appointed CEO, my biggest concern was, would this [job] allow me to truly say what I think? I needed to be myself to do a good job. Everybody does.”

What to make of these two views? Are people being disingenuous (or perhaps naive) when they aspire to bring their true selves to work? Certainly one might want to work in a company that makes you the best you can be without widely advertising the missteps you make along the way. Kegan is quick to point out that there are other ways to realize people’s full potential. But he also suggests that some people think they’d prefer an embarrassment-free work zone because they cannot imagine how something so painful at work could lead to something expansive and life changing.

Before you decide which view you agree with, take this assessment that Kegan and his associates have developed, and see how well suited you are to traveling down the no-spin path to fulfilling your highest potential.

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the July-August 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the July–August issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the TWO HBR Cartoon Caption Contests we’re running this month. The first contest, for our September issue, is at the bottom of this post, and the second contest, for our October issue, can be found here. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

Bob Eckstein

“Good. Now we’ll take things up a notch and have you check your work e-mails…”

Paula Pratt

“It works, but is it scalable?”

Kaamran Hafeez

“Admittedly, it’s a niche market.”

Crowden Satz

“We’ve updated the company manual.”

Bob Vojtko

And congratulations to our July–August caption contest winner, Lance Kelly of Manchester, Connecticut. Here’s his winning caption:

“I’m loving this blue ocean strategy.”

Cartoonist: Ken Krimstein

SEPTEMBER CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in the September magazine issue and win a free book. And don’t forget we’re running TWO caption contests this month—the second contest, for our October issue, can be found here. To be considered for either of this month’s contests, please submit your caption by August 3.

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers