Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1381

August 15, 2014

An Economic Explanation for Putin’s Recklessness

Why would Russian President Vladimir Putin push his country into a standoff with the West that is almost certain to hurt its economy? One popular answer is that, as Daniel Drezner put it, Putin “doesn’t care about the same things the West cares about” and is “perfectly happy to sacrifice economic growth for reputation and nationalist glory.”

That may be true. But looking at Russia’s growth trajectory over the past two decades suggests that economic issues may well play a role, just not necessarily in the ways you’d expect.

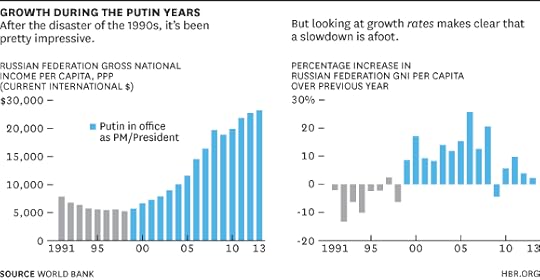

As you can see in the chart above, Putin has presided over a run of very strong economic growth. When he took power in 1999, Russians’ per capita income (in dollars, adjusted for purchasing power) had declined for seven of the eight previous years. Since then, it has risen in 14 of 15 years.

That’s not to say Putin was the cause of all this growth. Anders Aslund of the Peterson Institute of International Economics argued in 2008 that the Russian leader, then at the height of his economic success, ”should go down in history as one of the lucky ones who happened to be in the right place at the right time … but accomplished little that was positive.” For the first couple of years, as Aslund tells it, Putin continued the economic reforms that had begun during the Yeltsin era and had started to bear fruit just before Putin took over. He then began reversing those reforms to help his friends and punish his enemies, but rising prices for the huge quantities of oil and natural gas that Russia exports kept driving incomes higher.

Can you really expect ordinary Russians to take all of that into account? No. In general, a country’s citizens can be expected to care mainly about how fast their incomes rise, not how the growth is achieved or how sustainable it is. Economist Ray Fair’s 1978 study of nine decades of presidential election results in the U.S. found that recent economic growth was a pretty good predictor of whether the incumbent party would stay in office — unless war or scandal intervened. Fair’s model has its critics, but it seems reasonable to posit that a decade of rapid income growth (peaking at almost 26% a year in 2006) left Putin with a big reservoir of good will among the Russian people.

As the chart above shows, though, growth has settled into a much lower trend since the Great Recession. Energy prices have been flat, and the inefficient state of the rest of the economy has become a more noticeable drag. GDP growth of only 1.3% in 2013 even led to talk of a “growth crisis” for the Russian economy.

What is Vladimir Putin to do? Boosting the economy would likely require reforms (opening up the energy industry to foreign investors, improving the business climate with a more reliable regulatory and legal climate) that would loosen his grip on power and at best result in a modest growth uptick — especially compared to those crazy leaps of a decade ago. So Putin has gotten his country into a scrap with Ukraine and the West that is probably depressing growth, but has also rallied the country’s people around him. And it’s unlikely to hurt the economy that much, write economists Clifford G. Gaddy and Barry W. Ickes in one of a pair of enlightening recent essays:

Were it not so likely to be considered disrespectful, we might describe Russia as the cockroach of economies — primitive and inelegant in many respects but possessing a remarkable ability to survive in the most adverse and varying conditions. Perhaps a more appropriate metaphor is Russia’s own Kalashnikov automatic rifle — low-tech and cheap but almost indestructible.

That essay focuses on Russia’s likely resilience in the face of sanctions; the other (which I also linked to above in the discussion of Russia’s “growth crisis”) describes the obstacles to significantly faster growth. After reading them one can’t help but conclude that the economy does factor into Putin’s calculations — it’s just, that given his economic options, a Little Cold War may look more attractive to him than peace.

Why Certain Managers Thrive in Tough New Jobs

Why do some managers seem to enjoy unpleasant on-the-job learning experiences while others just want to quit? Emotional intelligence has something to do with it, according to a study of managers by Yuntao Dong of the University of Connecticut. The researchers found that a highly unpleasant developmental experience increased turnover intention about 20% among managers with low emotional intelligence but slightly decreased it among those with high EQ. Managers with high EQ, the ability to understand and manage emotions, reframe their developmental experiences as valuable opportunities rather than as threatening situations.

Networking for Introverts

The night before a conference where I was scheduled to speak, I found myself in a crowded bar just south of Greenwich Village. The organizers had arranged a VIP reception, and — having just moved to New York — I figured I should attend. Indeed, I had good conversations with four interesting people whom I’ll probably keep in touch with. But when I walked out the door an hour later, I was thrilled with my revelation: I’m never doing that again.

It wasn’t the fault of the conference or the bar or the attendees. It was my realization that I’ve always hated socializing in noisy environments where you have to scream to be heard. As an introvert, I find it overwhelming — and that means I’m not at my best when connecting. In fact, many people find networking in general to be stressful or distasteful. But I’ve come to realize that networking is downright enjoyable when you match it to your strengths and interests, rather than forcing yourself to attend what the business world presents as archetypal “networking events.” Here’s how I’ve embraced networking in my own way.

Create your own events. If you’re game for any kind of networking, you don’t have to think too hard about which types of events to attend; as long as it’s the right crowd, you can make the connections you need. But if you prefer “minimally stimulating environments,” as many introverts do, others’ choices — from boozy harbor cruises to swanky after parties — may not be right for you. Instead, I’m increasingly trying to control my networking environment by creating my own events. In the next couple of months, I’m planning to bring together “interest groups” of colleagues whom I think would enjoy each other for dinner parties, from female journalists to business authors to fellow attendees of a conference I enjoy.

Understand when you’re at your best. My circadian rhythms are fairly normal, but I’m definitely not a morning person. Early in my career, I dutifully signed up to attend 500-person networking breakfasts, because “that’s what you do” as a businessperson. I eventually realized the shock of waking up at 6 a.m. to get downtown in time was making my entire day less productive, so I swore them off. (I gave up early morning exercise for the same reason.) For introverts, networking requires a little more cognitive effort: it’s fun, but you have to psych yourself up to be “on.” I don’t need to have the additional burden of doing it when I’m tired. I now stack the deck in my favor by refusing any meetings before 8 am or after 9 pm.

Rate the likelihood of connecting. Every networking event should be subjected to a cost-benefit analysis: if you weren’t here, what would you be doing, instead? Running the numbers is particularly important for introverts, because even if the alternative isn’t something overtly productive like writing a new business proposal, the cost side of the equation can be steep: you may be exhausting yourself emotionally for hours or days afterward. Ask yourself who’s likely to attend, and whether they’re your target audience (however you define that — potential clients, interesting colleagues, etc.). Then follow up by asking how likely it is that you’ll actually get to connect with them. Large, loud events hinder your chances. If it’s an intimate dinner, I’ll almost always say yes; if it’s a raucous roofdeck gathering, I’ll probably sneak out the back.

Calibrate your schedule. Athletes understand they need time for muscle recovery, so they follow up intense training days with time off. Introverts should do the same. As I write this, I’m in the midst of a “writing day,” where my plan is to bang out three blog posts; my only “meeting” today is with a repairman. Yesterday, on the other hand, I had three in-person meetings and two conference calls. Batching my activities allows me to focus, and alternating between social and quiet time enables me to be at my best when I do interact with people. Even if a networking opportunity appears interesting, I’m likely to decline if it’s on the heels of several busy days; I’ve come to understand I won’t be able to tap its full potential because I’ll feel emotionally run down. On the other hand, I’m more likely to say yes to an event, even if it’s just outside my wheelhouse, if the timing works and I know I’ll be fresh and open to engaging with new people.

Finding the type of gatherings that work for you will make your networking much more successful — and more enjoyable. There’s a reason so many events take place in noisy bars: some people love that. For those of us without that predilection, we need to start saying no to torturing ourselves in the belief that it’ll ultimately be good for us. Instead, we have to reclaim networking and do it our own way.

August 14, 2014

Prevent Employees from Leaking Data

David Upton and Sadie Creese, both of Oxford, explain why the scariest threats are from insiders. For more, see The Danger from Within in the September 2014 issue of HBR.

Teams Can’t Innovate If They’re Too Comfortable

On a warm afternoon in June, a few dozen people gathered on a sun-dappled spot of lawn in Cambridge to discuss the very broad topic of modern leadership.

The head of a famous museum debated a senior exec from Google about what constitutes great design. A Broadway choreographer shared his hiring process with the mayor of a Midwestern city. A philanthropist and a magazine editor discussed new business models for publishing.

30 minutes of a 50-minute discussion were spent reformulating the questions, rather than searching for answers. (Einstein would have been proud.)

How often does this kind of deep conversation happen where you work? If you’re like most people, not often.

But this venue – Spark Camp – is designed for just such a thing. Spark Camp is a next-generation convener. They engineer productive collisions of people to tackle important topics, through clearer questions, challenging conversations, and listening with curiosity.

Funded by grant money and generous donors, with the luxury of inviting people to sit around on a grassy lawn for a whole weekend, you might think it’s easy for them to spark such conversations, to find such a diverse array of interesting people. It’s not. (For one thing, the organizers all have day jobs.)

Spark Camp is designed to bring together difference. Conveners Matt Thompson, Amanda Michel, Amy Webb, Jenny 8 Lee, and Andrew Pergam launched it because they were tired of going to conferences where they heard the same stories, by the same people, often without any opportunity for challenging the fundamental premise.

And their conference was visibly diverse (I later learned the demographic ratios were 50% women, 30% people of color, 25% LGBT, with a range of ages from 20 to 70). It’s part of what made the conversations so good: research from Kellogg shows that the cost of thinking with people like you hurts the rate of innovation – as measured by new ideas — by 15%. Thinking with people different from you improves the quality of decisions by nearly 50%. (Many other studies have shown similar results.)

I asked the Spark Camp organizers how they designed for these sorts of high quality interactions. Their approach can be applied to many organizations.

Decide difference matters. Everything starts with an intent, says Amanda Michel. “Amy Webb and I kept going to so many events where women were – at most — 10% of the speakers and about 10% of the audience and it struck us how deeply flawed this is. So we decided from the beginning we’d include 50% women. But this goes beyond gender, of course. We believe strongly in diversity for a few reasons. We think events should be largely representative — and recognize that in these times, being representative can actually be transformative. We think that diversity of experience and ideas helps people see problems and issues anew.”

Define what difference means. SparkCamp curation start with capabilities of difference. This includes cynics – those who challenge by nature– and cooperatives – those who build up others’ ideas. Also, dimensions such as: introverts and extroverts. Skill sets. Jobs at big and small institutions. A variety of industry backgrounds (arts, health, business, journalism, government, education). A range of experience levels from two years of work experience to 50. Levels of seniority. And, of course, race and socioeconomic differences. As Michel put it, “If you want to address the texture and nuance of complex problems, you need to bring that texture and nuance in the room.”

Be relentless. Matt Thompson described each person brought together as the “product of a very long and hard scavenger hunt.” No organization wins by saying “that can’t be done,” and it’s that same relentless energy that needs to fuel your process of bringing together people to work on a problem.

Measure Everything. Amy Webb – having written a best-selling book about how to use data to crack the dating system – says everything is tracked in an elaborate spreadsheet. The group measures and dissects data to learn from prior events as well as to adjust processes. For example if last-minute drop out rates are higher for women, they account for that by inviting more women upfront.

Set up ground rules. Sparkcamp says the goal is to learn from each other and to create together. Not by monologue, but by interchange. “We make it very clear that we’ve not asked them to attend because of their title, or to represent their organization; instead they’re there to be themselves,” Andy Pergam shared. These principles are openly shared as a filter to be used by both the organizers and the invitee to decide if they can sign up to be fully themselves, fully present, to foster the kind of openness that leads to breakthroughs.

All organizations are looking to increase their innovation success rate. But that isn’t going to be something you accidentally do. You don’t just drift into better behavior. You have to be intentional and deliberate.

Innovation is, most fundamentally, a people-based process. Which is why I found Spark Camp worth delving into. It wasn’t easy for the organizers to bring together difference; they estimate it probably takes fives times as much effort as it would to organize a more traditional event. And it wasn’t always easy for the attendees, either. Many attending expressed an intense discomfort at first. Asking themselves, “Why am I here? I have nothing in common with these people — what are we going to talk about?” But then what happened was incredibly fruitful: conversations were both more interesting, and more challenging.

To learn something new, you have to be uncomfortable. Our organizations are paying a high price for letting us work with only those we feel most comfortable with. When assumptions aren’t challenged, when questions aren’t posed, when new ideas aren’t thoroughly considered…you don’t invent a new solution to an old problem. Or find a new way to serve the next market. You simply miss out.

This data-driven and intentional approach that Spark Camp demonstrates has something all of us could take on. If we are going to create new outcomes, and be truly innovative, let’s design for it.

August 13, 2014

Why It’s Good to Be a “Technology Company”

Venture capitalist Chris Dixon’s declaration, after plunking $50 million down on Buzzfeed, that he was investing in a “technology company” has been causing a bit of head-scratching and gentle mockery in media circles. After all, what most of Buzzfeed’s 500 employees do is create lists and quizzes. That happens to be what many if not most magazine editors in the U.S. have been doing for the past 30-odd years. When magazine editors do it, it’s journalism. When Buzzfeed editors do it, it’s technology.

As Re/Code’s Peter Kafka points out, the $850 million valuation that the investment by Andreessen Horowitz (Dixon’s firm) puts on Buzzfeed is much lower than a true technology company of similar audience and maturity would get. But it’s much higher than what a conventional media company could hope to get. Buzzfeed is a technomedia company!

Or, more accurately, it’s a media company that’s been constructed around the latest means of finding audiences and selling things to them. Which you could, with some justification, call a technology. Here’s Dixon explaining his thinking on his blog:

Many of today’s great media companies were built on top of emerging technologies. Examples include Time Inc. which was built on color printing, CBS which was built on radio, and Viacom which was built on cable TV.

Now, he writes, we’re in the midst of another technological shift, in which more and more of the world’s news and entertainment are delivered via social networks to mobile devices — and Buzzfeed and its “100+ person tech team” are all over it. “BuzzFeed takes the internet and computer science seriously.”

These are not crazy arguments. John Huey, Martin Nisenholtz, and Paul Sagan paid a visit to HBR last year as they were completing their epic online oral history of the collision between old media and the internet, and they said the clearest lesson they learned was that organizations that had software engineers and Web enthusiasts in the room when big decisions were made navigated the seas of change more successfully than those that didn’t. And very few old media companies did.

It’s not that they didn’t know anything about technology — there were lots of experts in the technologies of printing, direct mail, audience measurement, and the like working at established media companies. It’s that they weren’t familiar with the new technologies that the industry was shifting to.

I’ve been spending some time lately with Dick Foster’s fascinating and underappreciated 1986 book Innovation: The Attacker’s Advantage. It’s a precursor — probably the most important precursor — to Clayton Christensen’s later work on disruptive innovation. In it, Foster argues that “technological discontinuities” were enabling upstart attackers to push aside market-leading defenders far more frequently than was then commonly understood.

One of his suggestions for would-be defenders (he worked at McKinsey, so that’s who he saw as the main audience for his advice): hire a CEO “who understands the process of scientific discovery.” Foster did not seem entirely comfortable with this wording — some of the potential discontinuities he discussed were in low-tech products like soda pop. But the point he was trying to make is that companies needed leaders who understood the technological underpinnings of their business, however simple those underpinnings might be, and thought hard about the limits of current technologies and the potential of new ones.

In the book, Foster describes the path of technological progress as a series of “S-curves” separated by discontinuous leaps. Like most S-curves, Foster’s looks less like an “S” than the left half of a bell curve: At the flat bottom left, investment in a new technology brings only modest rewards. At the top right, the curve flattens again as returns to investment diminish. In the middle, steep part of the curve, fortunes are made by whoever is the market leader at the time.

When you think about how news and entertainment have been delivered over the internet so far, four main S-curves come to mind: first proprietary networks, with AOL the market leader; then portals, with Yahoo No. 1; then search, with Google utterly dominant; and now social, with Facebook leading the way but other networks playing a big role as well. (And yeah, there are lots of other S-curves that could be drawn for the actual devices used, the kinds of internet connections, and the like. The world is never as simple as a consultant’s or professor’s model.)

The big question in Buzzfeed’s case is how long this social/mobile S-curve has to run. “I tend to think at least for the next five to 10 years that social is the thing,” is Dixon’s guess. “Nobody knows and I could be totally wrong.” For CBS, Time Inc., and Viacom, of course, the good times lasted for decades. In the internet era the cycles have been shorter. But that could be a transitional thing — and it’s not like the companies that dominated previous cycles have gone away. Google is a still a juggernaut. Yahoo and AOL, for all their troubles, are still profitable companies with multi-billion-dollar market caps (albeit single-digit billions in AOL’s case).

Of course, Buzzfeed isn’t master of this S-curve. For the moment, Facebook is and Buzzfeed is along for the ride. But it knows things about navigating it that other media companies don’t. And that’s worth something.

Use “Both-Brain” Marketing to Balance Creativity and Analytics

Marketing was once largely the preserve of creative, right-brain types, but the function needs—and is getting—a much larger mixture of data and analytics. Sometimes, though, there’s a danger of relying too heavily on analytics. What’s needed is the right balance, what we call a “both-brain” approach.

Pockets of this “both-brain” approach have existed in marketing for a while, but it’s now gathering speed and will become essential to future marketing success. Of course, knowing this is not the same as putting it into practice. Both-braining bumps up against process and resource constraints. And it requires a change in mindset and organizational culture.

Marketers will need to make a concerted effort to reshape their organizations, involving at least four steps:

Set the right tone at the top. Leaders have to paint an ambitious and inspiring vision of a both-brain organization. They have to acknowledge and champion the change that’s needed and model the necessary behavior. At Google Creative Lab, for example, executives demand brilliant, creative thinking and insights at the core of any campaign. But they don’t expect perfect translation of these insights into marketing content and execution right out of the gate. Instead, they deliberately champion post-launch testing, expecting that the creative content will be refined and perfected based on a data-driven analysis of live feedback from the marketplace.

Integrate both approaches into the production cycle. Marketers have traditionally worked on a long creative cycle bookended by (often limited) analytics. Testing and iteration have played little part. But progressive marketers are moving to shorter creative cycles punctuated by frequent testing, analysis and revision. The process produces marketing that is more engaging, better targeted, and much more effective at driving results.

Volkswagen’s collaboration with Google and several agencies for a digital ad campaign to promote its SmileDrive app is an example of combining creativity with analytics in this way. The app allows users to document car journeys and post content, increasing their driving enjoyment. To encourage target consumers to use the app, VW asked a group of influential driving enthusiasts to document their own journeys in VW loaner cars, and then made this content accessible through display ads. Google’s analytic tools helped identify and target precise user segments for the ads. The combination of targeting using analytics and engaging creative content resulted in three times the typical engagement level.

Design clear decision-making processes. With the marketing analytics available today, there’s a real danger of analysis paralysis. So marketers need to identify the specific decisions that could benefit from analytic insights, clarify the criteria used to make each decision, and only then gather the required data and perform the needed analyses. To avoid turf wars, project or campaign leaders should assign clear roles to both analytic and creative team members for each of these key decisions. These leaders will themselves need to model the both-brain sensibility and serve as active liaisons between the two camps as necessary.

Nourish both-brain skills with thoughtful training and incentives. Leaders will need to seek out, hire, and promote both creative and analytic talent. They’ll also have to cross-train team members on the importance of both left-brain and right-brain skills. To further build trust between analytic teams and their creative counterparts, leaders can co-locate the two groups and create both-brain teamlets that work together on multiple campaigns over time. And when both-brain collaboration works the way it should, they should highlight those campaigns and reward the individuals involved.

The infusion of analytics presents a huge opportunity to improve marketing’s performance. The challenge is to build an organization that can integrate both creative and analytic skills. It’s a job that requires investment and effort, but the payoff will be marketing that is both inspiring and effective.

Managers Can Motivate Employees with One Word

Human beings are profoundly social — we are hardwired to connect to one another and to want to work together. Frankly, we would never have survived as a species without our instinctive desire to live and work in groups, because physically we are just not strong or scary enough.

Tons of research has documented how important being social is to us. For instance, as neuroscientist Matt Lieberman describes in his book, Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect, our brains are so attuned to our relationships with other people that they quite literally treat social successes and failures like physical pleasures and pains. Being rejected, for instance, registers as a “hurt” in much the same way that a blow to the head might — so much so that if you take an aspirin you’ll actually feel better about your breakup.

David Rock, founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute, has identified relatedness — feelings of trust, connection, and belonging—as one of the five primary categories of social pleasures and pains (along with status, certainty, autonomy, and fairness). Rock’s research shows that the performance and engagement of employees who experience relatedness threats or failures will almost certainly suffer. And in other research, the feeling of working together has indeed been shown to predict greater motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, that magical elixir of interest, enjoyment, and engagement that brings with it the very best performance.

Theoretically, the modern workplace should be bursting with relatedness. Not unlike our hunter-gatherer ancestors, most of us are on teams. And teams ought to be a bountiful source of “relatedness” rewards.

But here’s the irony: While we may have team goals and team meetings and be judged according to our team performance, very few of us actually do our work in teams. Take me, for example: I conduct all the research I do with a team of other researchers. I regularly coauthor articles and books. My collaborators and I regularly meet to discuss ideas and to make plans. But I have never analyzed data with a collaborator sitting next to me, or run a participant through an experiment with another researcher at my side—and my coauthors and I have never ever typed sentences in the same room. Yes, many of the goals we pursue and projects we complete are done in teams, but unlike those bands of prehistoric humans banding together to take down a woolly mammoth, most of the work we do today still gets done alone.

So that, in a nutshell, is the weird thing about teams: They are the greatest (potential) source of connection and belonging in the workplace, and yet teamwork is some of the loneliest work that you’ll ever do.

So what we need is a way to give employees the feeling of working as a team, even when they technically aren’t. And thanks to new research by Priyanka Carr and Greg Walton of Stanford University, we now know one powerful way to do this: simply saying the word “together.”

In Carr and Walton’s studies, participants first met in small groups, and then separated to work on difficult puzzles on their own. People in the psychologically together category were told that they would be working on their task “together” even though they would be in separate rooms, and would either write or receive a tip from a team member to help them solve the puzzle later on. In the psychologically alone category, there was no mention of being “together,” and the tip they would write or receive would come from the researchers. All the participants were in fact working alone on the puzzles. The only real difference was the feeling that being told they were working “together” might create.

The effects of this small manipulation were profound: participants in the psychologically together category worked 48% longer, solved more problems correctly, and had better recall for what they had seen. They also said that they felt less tired and depleted by the task. They also reported finding the puzzle more interesting when working together, and persisted longer because of this intrinsic motivation (rather than out of a sense of obligation to the team, which would be an extrinsic motivation).

The word “together” is a powerful social cue to the brain. In and of itself, it seems to serve as a kind of relatedness reward, signaling that you belong, that you are connected, and that there are people you can trust working with you toward the same goal.

Executives and managers would be wise to make use of this word with far greater frequency. In fact, don’t let a communication opportunity go by without using it. I’m serious. Let “together” be a constant reminder to your employees that they are not alone, helping them to motivate them to perform their very best.

CMOs and CIOs Increasingly See Eye to Eye

For the past four years, Accenture has conducted an annual survey of chief marketing officers (CMOs) and chief information officers (CIOs) to understand the state of their collaboration. In that time, we’ve tracked dramatic changes in attitudes. The headline: today, 69 percent of CMOs say that they need to align and interact with IT on their strategic priorities. (Contrast this with 56 percent in 2012.) And 83 percent of CIOs say that they need to align and interact with Marketing. (It was 77 percent in 2012.)

On the one hand, this is a surprising finding; opinions do not normally shift so quickly among veteran executives. On the other hand, the change only reflects the shift going on in the priorities themselves. CMOs have moved quickly to place more emphasis on marketing IT (relative to the other activities and investments they oversee to build brands and drive revenue). In the latest survey, 52 percent of them put marketing IT at or near the top of their priorities (meaning they assigned it a “4” or “5” on a five-point scale). This is a 16-point jump over 2012. This change is mirrored by the 53 percent of CIOs who now put marketing IT at or near the top of their IT priorities – an 8-point jump over just one year earlier. When we asked why marketing and IT should collaborate more, the most cited reason was a simple one: “Marketing is more about digital now, which requires more technology.”

Few would argue with the notion that the two functions, often deeply siloed in large businesses, should work together more effectively to seize opportunities in today’s increasingly digital world. Interesting new combinations of social, mobile, analytics, and cloud technologies are being created, tested, and deployed at a rapid clip. Helping to support their collaboration is a shared sense of where the focus should be. Both marketing and IT leaders agreed that the top five marketing IT priorities include customer experience, customer analytics, social media, corporate website, and other web application development.

But collaboration is still challenged by the fact that the two functions work in different modes and toward objectives on different time horizons. A consistent point of friction across the years is marketers’ demand for speed. Particularly as teams tasked with enabling new customer experiences experiment with advanced digital marketing techniques, we hear from technology teams that they are scrambling to keep up.

Indeed, as the imperative to work together places new pressure on the relationship, there are signs of growing impatience on both sides. Forty percent of CMOs say their company’s IT team does not understand the urgency of integrating new data sources into their campaigns – an increase of 6 percentage points from last year’s survey. At the same time, 43 percent of CIOs complain that marketing requirements and priorities change too often for them to keep up. And the number of CIOs who believe that CMOs lack the ability to anticipate new digital channels? That’s grown from 11percent last year to 25 percent in 2014.

How can CMOs and CIOs make progress toward working together productively, rather than letting tensions spoil their teams’ collaborations? In the companies we see leading the way in marketing IT, leaders take specific actions to build trust and improve alignment:

Create a crisp vision on how digital capabilities will enable marketing objectives. The gap in scores between CMOs and CIOs suggests that many companies should start with a jointly developed vision for how digital technologies can enable marketing objectives to drive growth with efficient marketing spend. Marketing teams should invest time in establishing a digital vision and collaborate with IT to bring it to life. This is especially important as senior marketers recognize that digital is more than “just another channel” and they start working with executives across the business on new multi-channel operating models.

Prioritize and create the customer experiences that will significantly improve satisfaction and retention. Technology teams will have an easier time sustaining momentum and funding if Marketing can communicate specific visions for how individual customer experiences will be improved. Enabling customer experiences often requires the technology teams to create development efforts that cross organization boundaries well outside the scope of the marketing organization. Delivering customer impact and business value with a few early winners on key customer experiences can generate substantial momentum for additional investments.

Talk about the promise, price, and pace of service enablement available from external vendors. The technology teams recognize that not every capability should be developed within the company. Marketing teams should work with them to evaluate external options and collaborate on sourcing strategies that mix internal and external services to optimize performance, speed of implementation, and cost. This is especially important for areas where marketing is experimenting with emerging technologies in pilots or proof-of-concept initiatives.

The rapid convergence of CMOs’ and CIOs’ priorities in this year’s survey is driven by necessity. Companies are focusing on growth at the same time that customers’ expectations regarding digital capabilities are rising. Creating better customer experiences and delivering on brand promises will require ever closer collaboration among marketers and technologists – and we expect the awareness of that reality to keep growing in years to come.

Sometimes You Win, Sometimes You Lose, and Sometimes It’s Meaningless

If a pro basketball team’s opponent hits a better-than-expected proportion of its free throws — 80% versus 70% — the coach is half a percentage point more likely to change his starting lineup for the subsequent game, even though the opposing team’s free-throw average was beyond his control, says a group of researchers led by Lars Lefgren of Brigham Young University. Coaches frequently make strategic changes in response to irrelevant factors, especially after a loss, no matter how narrow or meaningless. This behavior is due to the outcome bias, which leads people to view random negative outcomes as the result of poor choices.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers