Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1377

August 25, 2014

Employers Aren’t Just Whining – the “Skills Gap” Is Real

Every year, the Manpower Group, a human resources consultancy, conducts a worldwide “Talent Shortage Survey.” Last year, 35% of 38,000 employers reported difficulty filling jobs due to lack of available talent; in the U.S., 39% of employers did. But the idea of a “skills gap” as identified in this and other surveys has been widely criticized. Peter Cappelli asks whether these studies are just a sign of “employer whining;” Paul Krugman calls the skills gap a “zombie idea” that “that should have been killed by evidence, but refuses to die.” The New York Times asserts that it is “mostly a corporate fiction, based in part on self-interest and a misreading of government data.” According to the Times, the survey responses are an effort by executives to get “the government to take on more of the costs of training workers.”

Really? A worldwide scheme by thousands of business managers to manipulate public opinion seems far-fetched. Perhaps the simpler explanation is the better one: many employers might actually have difficulty hiring skilled workers. The critics cite economic evidence to argue that there are no major shortages of skilled workers. But a closer look shows that their evidence is mostly irrelevant. The issue is confusing because the skills required to work with new technologies are hard to measure. They are even harder to manage. Understanding this controversy sheds some light on what employers and government need to do to deal with a very real problem.

This issue has become controversial because people mean different things by “skills gap.” Some public officials have sought to blame persistent unemployment on skill shortages. I am not suggesting any major link between the supply of skilled workers and today’s unemployment; there is little evidence to support such an interpretation. Indeed, employers reported difficulty hiring skilled workers before the recession. This illustrates one source of confusion in the debate over the existence of a skills gap: distinguishing between the short and long term. Today’s unemployment is largely a cyclical matter, caused by the recession and best addressed by macroeconomic policy. Yet although skills are not a major contributor to today’s unemployment, the longer-term issue of worker skills is important both for managers and for policy.

Nor is the skills gap primarily a problem of schooling. Peter Cappelli reviews the evidence to conclude that there are not major shortages of workers with basic reading and math skills or of workers with engineering and technical training; if anything, too many workers may be overeducated. Nevertheless, employers still have real difficulties hiring workers with the skills to deal with new technologies.

Why are skills sometimes hard to measure and to manage? Because new technologies frequently require specific new skills that schools don’t teach and that labor markets don’t supply. Since information technologies have radically changed much work over the last couple of decades, employers have had persistent difficulty finding workers who can make the most of these new technologies.

Consider, for example, graphic designers. Until recently, almost all graphic designers designed for print. Then came the Internet and demand grew for web designers. Then came smartphones and demand grew for mobile designers. Designers had to keep up with new technologies and new standards that are still changing rapidly. A few years ago they needed to know Flash; now they need to know HTML5 instead. New specialties emerged such as user-interaction specialists and information architects. At the same time, business models in publishing have changed rapidly.

Graphic arts schools have had difficulty keeping up. Much of what they teach becomes obsolete quickly and most are still oriented to print design in any case. Instead, designers have to learn on the job, so experience matters. But employers can’t easily evaluate prospective new hires just based on years of experience. Not every designer can learn well on the job and often what they learn might be specific to their particular employer.

The labor market for web and mobile designers faces a kind of Catch-22: without certified standard skills, learning on the job matters but employers have a hard time knowing whom to hire and whose experience is valuable; and employees have limited incentives to put time and effort into learning on the job if they are uncertain about the future prospects of the particular version of technology their employer uses. Workers will more likely invest when standardized skills promise them a secure career path with reliably good wages in the future.

Under these conditions, employers do, have a hard time finding workers with the latest design skills. When new technologies come into play, simple textbook notions about skills can be misleading for both managers and economists.

For one thing, education does not measure technical skills. A graphic designer with a bachelor’s degree does not necessarily have the skills to work on a web development team. Some economists argue that there is no shortage of employees with the basic skills in reading, writing and math to meet the requirements of today’s jobs. But those aren’t the skills in short supply.

Other critics look at wages for evidence. Times editors tell us “If a business really needed workers, it would pay up.” Gary Burtless at the Brookings Institution puts it more bluntly: “Unless managers have forgotten everything they learned in Econ 101, they should recognize that one way to fill a vacancy is to offer qualified job seekers a compelling reason to take the job” by offering better pay or benefits. Since Burtless finds that the median wage is not increasing, he concludes that there is no shortage of skilled workers.

But that’s not quite right. The wages of the median worker tell us only that the skills of the median worker aren’t in short supply; other workers could still have skills in high demand. Technology doesn’t make all workers’ skills more valuable; some skills become valuable, but others go obsolete. Wages should only go up for those particular groups of workers who have highly demanded skills. Some economists observe wages in major occupational groups or by state or metropolitan area to conclude that there are no major skill shortages. But these broad categories don’t correspond to worker skills either, so this evidence is also not compelling.

To the contrary, there is evidence that select groups of workers have been had sustained wage growth, implying persistent skill shortages. Some specific occupations such as nursing do show sustained wage growth and employment growth over a couple decades. And there is more general evidence of rising pay for skills within many occupations. Because many new skills are learned on the job, not all workers within an occupation acquire them. For example, the average designer, who typically does print design, does not have good web and mobile platform skills. Not surprisingly, the wages of the average designer have not gone up. However, those designers who have acquired the critical skills, often by teaching themselves on the job, command six figure salaries or $90 to $100 per hour rates as freelancers. The wages of the top 10% of designers have risen strongly; the wages of the average designer have not. There is a shortage of skilled designers but it can only be seen in the wages of those designers who have managed to master new technologies.

This trend is more general. We see it in the high pay that software developers in Silicon Valley receive for their specialized skills. And we see it throughout the workforce. Research shows that since the 1980s, the wages of the top 10% of workers has risen sharply relative to the median wage earner after controlling for observable characteristics such as education and experience. Some workers have indeed benefited from skills that are apparently in short supply; it’s just that these skills are not captured by the crude statistical categories that economists have at hand.

And these skills appear to be related to new technology, in particular, to information technologies. The chart shows how the wages of the 90th percentile increased relative to the wages of the 50th percentile in different groups of occupations. The occupational groups are organized in order of declining computer use and the changes are measured from 1982 to 2012. Occupations affected by office computing and the Internet (69% of these workers use computers) and healthcare (55% of these workers use computers) show the greatest relative wage growth for the 90th percentile. Millions of workers within these occupations appear to have valuable specialized skills that are in short supply and have seen their wages grow dramatically.

This evidence shows that we should not be too quick to discard employer claims about hiring skilled talent. Most managers don’t need remedial Econ 101; the overly simple models of Econ 101 just don’t tell us much about real world skills and technology. The evidence highlights instead just how difficult it is to measure worker skills, especially those relating to new technology.

What is hard to measure is often hard to manage. Employers using new technologies need to base hiring decisions not just on education, but also on the non-cognitive skills that allow some people to excel at learning on the job; they need to design pay structures to retain workers who do learn, yet not to encumber employee mobility and knowledge sharing, which are often key to informal learning; and they need to design business models that enable workers to learn effectively on the job (see this example). Policy makers also need to think differently about skills, encouraging, for example, industry certification programs for new skills and partnerships between community colleges and local employers.

Although it is difficult for workers and employers to develop these new skills, this difficulty creates opportunity. Those workers who acquire the latest skills earn good pay; those employers who hire the right workers and train them well can realize the competitive advantages that come with new technologies.

Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified

You’ve probably heard the following statistic: Men apply for a job when they meet only 60% of the qualifications, but women apply only if they meet 100% of them.

The finding comes from a Hewlett Packard internal report, and has been quoted in Lean In, The Confidence Code and dozens of articles. It’s usually invoked as evidence that women need more confidence. As one Forbes article put it, “Men are confident about their ability at 60%, but women don’t feel confident until they’ve checked off each item on the list.” The advice: women need to have more faith in themselves.

I was skeptical, because the times I had decided not to apply for a job because I didn’t meet all the qualifications, faith myself wasn’t exactly the issue. I suspected I wasn’t alone.

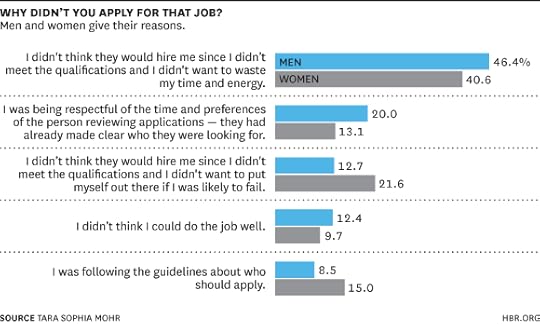

So I surveyed over a thousand men and women, predominantly American professionals, and asked them, “If you decided not to apply for a job because you didn’t meet all the qualifications, why didn’t you apply?”

According to the self-report of the respondents, the barrier to applying was not lack of confidence. In fact, for both men and women, “I didn’t think I could do the job well” was the least common of all the responses. Only about 10% of women and 12% of men indicated that this was their top reason for not applying.

Men and women also gave the same most common reason for not applying, and it was by far the most popular, twice as common as any of the others, with 41% of women and 46% of men indicating it was their top reason: “I didn’t think they would hire me since I didn’t meet the qualifications, and I didn’t want to waste my time and energy.”

In other words, people who weren’t applying believed they needed the qualifications not to do the job well, but to be hired in the first place. They thought that the required qualifications were…well, required qualifications. They didn’t see the hiring process as one where advocacy, relationships, or a creative approach to framing one’s expertise could overcome not having the skills and experiences outlined in the job qualifications.

What held them back from applying was not a mistaken perception about themselves, but a mistaken perception about the hiring process.

This is critical, because it suggests that if the HP finding speaks to a larger trend, women don’t need to try and find that elusive quality, “confidence,” they just need better information about how hiring processes really work.

This is why, I think, the Hewlett Packard report finding is so often quoted, so eagerly shared amongst women, and so helpful. For those women who have not been applying for jobs because they believe the stated qualifications must be met, the statistic is a wake-up call that not everyone is playing the game that way. When those women know others are giving it a shot even when they don’t meet the job criteria, they feel free to do the same.

Another 22% of women indicated their top reason was, “I didn’t think they would hire me since I didn’t meet the qualifications and I didn’t want to put myself out there if I was likely to fail.” These women also believed the on-paper “rules” about who the job was for, but for them, the cost of applying was the risk of failure – rather than the wasted time and energy. Notably, only 13% of men cited not wanting to try and fail as their top reason. Women may be wise to be more concerned with potential failure; there is some evidence that women’s failures are remembered longer than men’s. But that kind of bias may lead us to become too afraid of failure—avoiding it more than is needed, and in ways that don’t serve our career goals. The gender differences here suggest we need to expand the burgeoning conversation about women’s relationship with failure, and explore how bias, stereotype threat, the dearth of women leaders, and girls’ greater success in school all may contribute to our greater avoidance of failure.

There was a sizable gender difference in the responses for one other reason: 15% of women indicated the top reason they didn’t apply was because “I was following the guidelines about who should apply.” Only 8% of men indicated this as their top answer. Unsurprisingly, given how much girls are socialized to follow the rules, a habit of “following the guidelines” was a more significant barrier to applying for women than men.

All three of these barriers, which together account for 78% of women’s reasons for not applying, have to do with believing that the job qualifications are real requirements, and seeing the hiring process as more by-the-book and true to the on paper guidelines than it really is. It makes perfect sense that women take written job qualifications more seriously than men, for several reasons:

First, it’s likely that due to bias in some work environments, women do need to meet more of the qualifications to be hired than do their male counterparts. For instance, a McKinsey report found that men are often hired or promoted based on their potential, women for their experience and track record. If women have watched that occur in their workplaces, it makes perfect sense they’d be less likely to apply for a job for which they didn’t meet the qualifications.

Second, girls are strongly socialized to follow the rules and in school are rewarded, again and again, for doing so. In part, girls’ greater success in school (relative to boys) arguably can be attributed to their better rule following. Then in their careers, that rule-following habit has real costs, including when it comes to adhering to the guidelines about “who should apply.”

Third, certifications and degrees have historically played a different role for women than for men. That history can, I think, lead women to see the workplace as more orderly and meritocratic than it really is. As a result we may overestimate the importance of our formal training and qualifications, and underutilize advocacy and networking.

When I went into the work world as a young twenty-something, I was constantly surprised by how often, it seemed, the emperor had no clothes. Major decisions were made and resources were allocated based not on good data or thoughtful reflection, but based on who had built the right relationships and had the chutzpah to propose big plans.

It took me a while to understand that the habits of diligent preparation and doing quality work that I’d learned in school were not the only—or even primary—ingredients I needed to become visible and successful within my organization.

When it comes to applying for jobs, women need to do the same. Of course, it can’t hurt to believe more in ourselves. But in this case, it’s more important that we believe less in what appear to be the rules.

Different Kinds of Cuteness Affect Us in Different Ways

At an on-campus taste test, research participants who used a cute scoop designed to look like a smiling adult female served themselves about 30% more ice cream than those who used a plain scoop, say Gergana Y. Nenkov of Boston College and Maura L. Scott of Florida State University. This and other experiments demonstrate that exposure to cute, whimsical images increases consumers’ indulgent consumption, as long as the particular form of cuteness doesn’t stimulate thoughts of babies; past research has shown that images of babies prompt careful, caretaking behavior.

Why Saving Work for Tomorrow Doesn’t Work

Do you frequently tell yourself that you’ll do better “next time” and then don’t change when the time comes? Do you often decide to do something “later” only to find that it never gets done?

If you answered “yes” to either one of these questions, you’re probably ignoring the fact that your behavior today is a strong indicator of your behavior tomorrow.

You’re not alone. In The Willpower Instinct, Kelly McGonigal shares how, in a research study, participants were much less likely to exert willpower in making healthy choices when they thought they would have another opportunity the following week. Given the option of a fat-free yogurt versus a Mrs. Field’s cookie, 83% of those who thought they’d have another opportunity the following week chose the cookie. In addition, 67% thought they would pick yogurt the next time, but only 36% made a different choice. Meanwhile, only 57% of the people who saw this as their only chance indulged.

The same pattern of overoptimism about the future held true in a study about people predicting how much they would exercise in the future. When asked to predict their exercise realistically — and even faced with cold, hard data about their previous exercise patterns — individuals were still overly optimistic that “tomorrow would be different.”

Eating and exercise habits are all well and good, but as an expert in effective time investment, I’ve seen too many individuals procrastinate at work because they think, “I’ll get a lot done later.” Unfortunately, banking on future time rarely aligns with productive results. This mindset leads to unconscious self-sabotage because individuals are not taking advantage of the opportunity to get tasks done right now, and when later comes, they find themselves feeling guilty, burned out, and frustrated. They fall back on their habits to put work off, and it doesn’t get accomplished.

This pattern of behavior appears on the job when the only thing you accomplish during the day is answering email because you assume you’ll work better later when no one else is the office. But after everyone’s left at the end of the day, you’re too tired to think straight and just go home without getting anything done. Or it shows up when you choose to not make any progress on a project in small windows of time available because you’re waiting for an open day to knock it out all at once. That day never comes, leaving you scrambling at the last minute. Or it can spring up when you say “yes” to every meeting invite and leave no time to do actual work. Then you wonder why you feel like you’re always frantically working and never have time to relax.

Unless you make a conscious effort to change your behavior, poor time management today will only lead to poor time management tomorrow. Consider these two approaches to dramatically increase your productivity.

Eliminate future options. If you have a tendency, like many overwhelmed individuals, to tell yourself that that you’ll get your important work done later — maybe at night or on the weekend — you increase your chance of procrastination during the day. In truth, you can find it difficult to efficiently get things done later because you feel tired and resentful of the fact that you never have any guilt-free downtime. To overcome this psychological loophole, you need to eliminate the option to do something later.

First, challenge yourself to find specified times during your workday to complete your commitments. Look at your project list and estimate approximately how long it will take you to get certain items done. For example, if you have a presentation at the end of the month, determine how long it will take you to gather the information, put together the presentation, review it with your team, and run through it. Then assign specific times in your schedule between now and the presentation for you to complete each piece. This approach of fusing your to-do list with your calendar will help you realize that if you don’t move ahead on key projects, you will run out of time. There’s no option to simply do the work tomorrow because tomorrow has a new set of tasks assigned to it.

In addition, eliminate free time after hours. If you see an open window on your calendar, you’ll be tempted to put off work, knowing there’s an opportunity later — even if that cuts into personal time. Instead, fill that time with personal commitments. This could mean going out to dinner with a friend, spending the evening at your kids’ soccer game, going to the gym, or moving ahead a side project. By determining what you want to do outside of the office, you motivate yourself to make the best use of your time during the day so that you don’t need to cancel your evening commitments.

Reduce variability in your schedule. If you justify surfing the Internet most of the day because you tell yourself that you’ll work nonstop later, you’re setting yourself up for frustration. When you do attempt to tackle that work, you’ll either feel so guilty about your lack of productivity that it will distract you from the task at hand, or you’ll push yourself so hard that you’ll burn out.

Fortunately, there’s a way to outsmart your mental tricks. Studies done by behavioral economist Howard Rachlin show that smokers told to reduce variability in their smoking behavior — to smoke the same amount of cigarettes each day — gradually decreased their overall smoking, even though they were not told to smoke less. By focusing on the fact that if they smoked a pack of cigarettes today, they would need to smoke a pack the next day and the next, they found smoking that pack less appealing.

You can apply the same principle to motivate effective time management. Instead of telling yourself, “It’s OK if I surf the Internet for half the day because I’ll get so much done later this week,” ask yourself this question: “Do I want to surf the Internet for half the day for the rest of my life?” Your answer will probably be, “Of course not. That would be a waste of time.” You can then decide to dedicate that chunk of time to something more productive on a regular basis. Choosing to work the same amount each day with little variation on your schedule takes away the mental loophole that allows you to escape from getting things done now.

Using the present moment wisely instead of banking on time in the future can help you stay committed to your goals. If you have a project at work you’ve avoided for months or some languishing expense reports to file, think about how you can apply these strategies to move forward on those items today.

August 22, 2014

How Watson Changed IBM

Remember when IBM’s “Watson” computer competed on the TV game show “Jeopardy” and won? Most people probably thought “Wow, that’s cool,” or perhaps were briefly reminded of the legend of John Henry and the ongoing contest between man and machine. Beyond the media splash it caused, though, the event was viewed as a breakthrough on many fronts. Watson demonstrated that machines could understand and interact in a natural language, question-and-answer format and learn from their mistakes. This meant that machines could deal with the exploding growth of non-numeric information that is getting hard for humans to keep track of: to name two prominent and crucially important examples, keeping up with all of the knowledge coming out of human genome research, or keeping track of all the medical information in patient records.

So IBM asked the question: How could the fullest potential of this breakthrough be realized, and how could IBM create and capture a significant portion of that value? They knew the answer was not by relying on traditional internal processes and practices for R&D and innovation. Advances in technology — especially digital technology and the increasing role of software in products and services — are demanding that large, successful organizations increase their pace of innovation and make greater use of resources outside their boundaries. This means internal R&D activities must increasingly shift towards becoming crowdsourced, taking advantage of the wider ecosystem of customers, suppliers, and entrepreneurs.

IBM, a company with a long and successful tradition of internally-focused R&D activities, is adapting to this new world of creating platforms and enabling open innovation. Case in point, rather than keep Watson locked up in their research labs, they decided to release it to the world as a platform, to run experiments with a variety of organizations to accelerate development of natural language applications and services. In January 2014 IBM announced they were spending $1 billion to launch the Watson Group, including a $100 million venture fund to support start-ups and businesses that are building Watson-powered apps using the “Watson Developers Cloud.” More than 2,500 developers and start-ups have reached out to the IBM Watson Group since the Watson Developers Cloud was launched in November 2013.

So how does it work? First, with multiple business models. Mike Rhodin, IBM’s senior vice president responsible for Watson, told me, “There are three core business models that we will run in parallel. The first is around industries that we think will go through a big change in “cognitive” [natural language] computing, such as financial services and healthcare. For example, in healthcare we’re working with The Cleveland Clinic on how medical knowledge is taught. The second is where we see similar patterns across industries, such as how people discover and engage with organizations and how organizations make different kinds of decisions. The third business model is creating an ecosystem of entrepreneurs. We’re always looking for companies with brilliant ideas that we can partner with or acquire. With the entrepreneur ecosystem, we are behaving more like a Silicon Valley startup. We can provide the entrepreneurs with access to early adopter customers in the 170 countries in which we operate. If entrepreneurs are successful, we keep a piece of the action.”

IBM also had to make some bold structural moves in order to create an organization that could both function as a platform as well as collaborate with outsiders for open innovation. They carved out The Watson Group as a new, semi-autonomous, vertically integrated unit, reporting to the CEO. They brought in 2000 people, a dozen projects, a couple of Big Data and content analytics tools, and a consulting unit (outside of IBM Global Services). IBM’s traditional annual budget cycle and business unit financial measures weren’t right for Watson’s fast pace, so, as Mike Rhodin told me, “I threw out the annual planning cycle and replaced it with a looser, more agile management system. In monthly meetings with CEO Ginni Rometty, we’ll talk one time about technology, and another time about customer innovations. I have to balance between strategic intent and tactical, short-term decision-making. Even though we’re able to take the long view, we still have to make tactical decisions.”

More and more, organizations will need to make choices in their R&D activities to either create platforms or take advantage of them. Those with deep technical and infrastructure skills, like IBM, can shift the focus of their internal R&D activities toward building platforms that can connect with ecosystems of outsiders to collaborate on innovation. The second and more likely option for most companies is to use platforms like IBM’s or Amazon’s to create their own apps and offerings for customers and partners. In either case, new, semi-autonomous agile units, like IBM’s Watson Group, can help to create and capture huge value from these new customer and entrepreneur ecosystems.

Is the Future of Shopping No Shopping at All?

In a survey on what he terms "predictive shopping," Harvard Law professor Cass Sustein found that 41% of people would "enroll in a program in which the seller sent you books that it knew you would purchase, and billed your credit card." That number went down to 29% if the company didn't ask for your consent first.

But what if the products and services were different, like a sensor that knew you were almost out of dish detergent? Without consent, were people willing to have a company charge their account and send them more detergent? Most people (61%) weren't. But the results were a bit more interesting when Sustein did a similar survey among university students. While most still weren't into being charged automatically for books they might like, "69% approved of automatic purchases by the home monitor, even without consent." The professor posits that "among younger people, enthusiasm is growing for predictive shopping, especially for routine goods where shopping is an annoyance and a distraction."

It's Not the BusWhich Mode of Travel Provides the Happiest Commute?CityLab

While the results from a recent McGill University study aren't especially surprising — and consist of a McGill-specific survey sample — they do add credence to what many people already know in their commuting heart of hearts: That walking, biking, or taking a commuter train to work is much more satisfying than driving or taking the subway or bus. My significant other, for example, loves biking to work because it's both enjoyable and on his own timeline — he pretty much always knows when he's going to arrive at work, which diminishes his extreme dislike of idling in traffic for no apparent reason (I don't mind it as much because of my interest in singing loudly, and poorly, in the car). And a long train ride can allow for reading or doing work, making the time more productive.

But there were some surprises: Bus riders and cyclists — both of whom travel about 22 minutes to work — had very different levels of satisfaction. So, time spent commuting isn't necessarily a consistent predictor of happiness. And, in the end, "people expressed more happiness with their commute when the mode they took was the mode they wanted to take."

Step Up, Employers It's Not a Skills Gap: U.S. Workers are Overqualified, UndertrainedBusinessweek

Add this research from Peter Cappelli to the ongoing debate about the skills gap. According to the Wharton professor, and explained by Businessweek's Matthew Philips, much of the problem lies in how we do (or don't) train employees. Back in 1979, for example, young American workers received 2.5 weeks of training per year; by 1991, only 17% of employees said they received any formal training within the year. And by 2011, a mere 21% of Americans had received any training within the past five years. The prevailing argument is that companies no longer train their employees because it's a bad investment (top talent will end up leaving anyway), and because they're relying on internships to teach young workers. But Cappelli says that "the fear of having a competitor reap the rewards of your investment are overblown" — to the detriment of both companies and workers. In the end, says Philips, "the problem may not be the skills workers ostensibly lack. It may be that employers' expectations are out of whack."

YesCan a Robot Be Too Nice?Boston Globe

As robots and algorithms become more and more central to pretty much everything we do, the question of how humans and robots interact becomes more and more important (I mean, just look at the robot bellhop). Leon Neyfakh does a great job of rounding up all the ways researchers are trying to nail down what types of robot personalities people respond to, and in what circumstances. When it comes to robot nurses, for example, people prefer an outgoing and assertive personality. However, people were not at all confident in the protective abilities of extraverted security guard robots. So the future is looking more and more like a place where "it's not enough for a machine to have an agreeable personality — it needs to have the right personality." And as researchers aim to figure out what these personalities are and how they might change depending on the circumstances (yes, it's conceivable that one robot personality could migrate between all the devices you use throughout the day), Neyfakh observes what always seems to be the bottom line when we talk about robots and their human pals: "What the ideal machine personalities turn out to be may expose needs and prejudices we're not even aware we have."

From Sentiment to SuccessWhy Uber Just Hired Obama's Campaign GuruWired

Uber's great and all, except for one tiny problem: A lot of countries around the world think its business model is illegal. It's through this lens that the company's recent hire makes brilliant sense: David Plouffe, President Obama's 2008 campaign manager. Plouffe, as Wired's Marcus Wohlsen writes, was instrumental in "turning sentiment into success" six years ago. Plouffe engineered this through data — collecting it among potential voters and then micro-targeting based on the intelligence the campaign gathered. Uber, of course, gathers similar real-time data – data that could be used in a grassroots sort of way: Uber devotees who may not be aware of the company's regulatory problems can be recruited with specific messages to sign petitions and lobby their government representatives. Wohlsen puts this challenge nicely: "To survive, Uber is now about more than rides. It's about turning out the base."

BONUS BITS You Aren't What You Wear

Yoga Poseurs: Athletic Gear Soars, Outpacing Sport Itself (Wall Street Journal)

This Pair of Bionic Pants Is a Chair That You Wear (Gizmodo)

Oh, This Bracelet? It's Just My Wearable Device Charger (Mashable)

Great Leadership Isn’t About You

The year 1777 was not a particularly good time for America’s newly formed revolutionary army. Under General George Washington’s command, some 11,000 soldiers made their way to Valley Forge. Following the latest defeat in a string of battles that left Philadelphia in the hands of British forces, these tired, demoralized, and poorly equipped early American heroes knew they now faced another devastating winter.

Yet history clearly records that despite the harsh conditions and lack of equipment that left sentries to stand on their hats to prevent frostbite to their feet, the men who emerged from this terrible winter never gave up. Why? Largely because of the inspiring and selfless example of their leader, George Washington. He didn’t ask the members of his army to do anything he wouldn’t do. If they were cold, he was cold. If they were hungry, he went hungry. If they were uncomfortable, he too choose to experience the same discomfort.

The lesson Washington’s profoundly positive example teaches is that leading people well isn’t about driving them, directing them, or coercing them; it is about compelling them to join you in pushing into new territory. It is motivating them to share your enthusiasm for pursuing a shared ideal, objective, cause, or mission. In essence, it is to always conduct yourself in ways that communicates to others that you believe people are always more important than things.

Donald Walters, in his insightful little book, The Art of Leadership, provides a compelling example of how this perspective plays out in the most unlikely of places: the battlefield. Walters points out, “The difference between great generals and mediocre ones may be attributed to the zeal great generals have been able to inspire in their men. Some excellent generals have been master strategists, and have won wars on this strength alone. Greatness, however, by very definition implies a great, an expanded view. It transcends intelligence and merely technical competence. It implies an ability to see the lesser in relation to the greater; the immediate in relation to the long term; the need for victory in relations to the needs that will arise once victory has been achieved.”

As a general myself, I can confirm that achieving my mission, be it in training a new generation of capable men and women for service, promoting peace, or achieving victory in combat, is paramount. Yet this doesn’t imply that I should indiscriminately pursue my goals or blindly pursue my objectives at all costs. What Walters’ wise words strive to remind us of is that leadership, be it as a general in the military, an executive in the boardroom, a pastor serving a congregation, or a parent providing for a family, isn’t about exercising power over people, but rather, it’s about finding effective ways to work with people.

The most effective form of leadership is supportive. It is collaborative. It is never assigning a task, role or function to another that we ourselves would not be willing to perform. For all practical purposes, leading well is as simple as remembering to remain others-centered instead of self-centered. To do this, I try to keep these four imperatives in mind:

Listen to other people’s ideas, no matter how different they may be from your own: There’s ample evidence that the most imaginative and valuable ideas tend not to come from the top of an organization, but from within an organization. Be open to others opinions; what you hear may make the difference between merely being good and ultimately becoming great.

Embrace and promote a spirit of selfless service: People, be it employees, customers, constituents, or colleagues, are quick to figure out which leaders are truly dedicated to helping them succeed and which are only interested in promoting themselves at others’ expense. Be willing to put others’ legitimate needs and desires first and trust that they will freely give you the best they have to give.

Ask great questions: The most effective leaders know they don’t have all the answers. Instead, they constantly welcome and seek out new knowledge and insist on tapping into the curiosity and imaginations of those around them. Take it from Albert Einstein: “I have no special talent,” he claimed. “I am only passionately curious.” Be inquisitive. Help tap others’ hidden genius one wise question and courageous conversation at a time.

Don’t fall prey to your own publicity: Spin and sensationalism is an attractive angle to take in today’s self-promoting society. Yet the more we get accustomed to seeking affirmation or basking in the glow of others’ praise and adulation, the more it dilutes our objectivity, diminishes our focus, and sets us up to believe others are put in our path to serve our needs. Be careful not to become prideful; it will only set you up for a fall.

Those who serve under an effective general know well that he or she would ask nothing of others that they would not first do themselves. Such a leader believes with all their heart that they are one with their people, not superior to them. They know that they are simply doing a job together.

The need to reimagine and recast how we think about leadership has never been greater. In my view, too many of us have allowed our understanding of leadership to grow stagnant, contributing to why we face so many daunting problems in our society today. Now is the time to discover the leader within all of us. Now is the time to accept that leadership is meant to be more verb than noun, more active than passive.

Now is the time to not lose sight of the fact that people, be it in warfare, politics, religion, education, or business, are always more important than things.

Are you game?

Your Content Strategy Is Also a Recruiting Strategy

I recently asked a friend in California about the drought. “Nothing has changed,” he said. “There may be an emergency, but we’re still watering our lawns.”

There’s a similar crisis in the private sector, and plenty of leaders are approaching it with the same mentality as my friend.

But this time, it’s not the lawns that are drying up; it’s the talent pool.

Much like the drought, there are several factors contributing to this crisis. The first is generational. As Boomers retire, they’re leaving behind vacancies that younger workers aren’t equipped to fill.

The second is the recession. At its height, 60 percent of the workforce planned to seek new employment once the economy bounced back. After it did, 54 percent of companies lost top talent within just six months. These free agents are demanding unique work cultures and competitive development opportunities.

And with a shrinking labor pool that’s more mobile than ever, competition among potential employers is fierce. While corporate recruiters provide stopgap solutions, there’s a better way to attract and retain talent.

When it’s done right, digital content can have the same transformative impact on HR as it does on marketing. It’s simple: Great content attracts great people, and it encourages the people who are creating it to stick around.

Imagine that the ideal candidate finds an article that you published in an outside publication. As she reads the article, she develops a deeper understanding of your industry niche.

Clicking through to your social media presence, she finds herself immersed in your team’s content. Your blog posts, LinkedIn discussions, and tweets come together to create a clear picture of what it’s like to work at your company. The candidate feels a sense of connection to your corporate culture and decides to send in her résumé.

At the interview table, she proves herself knowledgeable about your business strategy. She understands the industry and has a clear idea of how she can contribute to growth. While other interviews were stiff and formal, this one is conversational and exciting.

The candidate gets the job. Because she has access to all of your digital content, much of her training is self-directed, and it begins immediately. This new hire is ready to add value the moment she joins the team.

If this seems implausible, then come talk to my staff. Our content is our most powerful recruiting tool. Many employees followed the same path as the hypothetical candidate, and in three years, only one employee has chosen to leave.

A simple LinkedIn page won’t turn the tide in your recruitment efforts, however. To wield digital content as an effective HR tool, you’ll need to establish in-depth strategies and processes.

Although the marketing department will likely do most of the work, rigid silos will be the death of your content. The effort must be a collaborative one — with your HR, PR, sales, and social media teams all contributing.

As a first step, incorporate your HR goals into your overall content strategy. How will you reach potential hires? How can you differentiate your company?

From there, put a system in place. Designate subject matter experts, and establish an editorial calendar. All of the gears — from writing and editing to social media — must be strategically aligned before moving forward.

While a good system is critical, it won’t ensure good content. During the creative process, prioritize authenticity above all else. Self-promotion will only damage your credibility, so encourage your team to share genuine insights. Otherwise, you’re wasting resources. (For a lesson in authentic vulnerability, read this letter from Target’s CMO, Jeff Jones.)

An Edelman study revealed that when it comes to providing company information, the public trusts employees more than CEOs. This makes sense. Ultimately, employees are the ones slugging it out on the front lines. They have every reason to tell it like it is.

Therefore, it’s in your best interests to build custom-made soapboxes for your team. When your best employees speak their minds, they attract like-minded people. And self-expression is a vital part of feeling valued and fulfilled.

Finally, make sure to track the impact of your content. Capturing users’ email addresses with a downloadable piece of content allows you to observe readers interacting with documents by attaching their identity to their actions.

This data is invaluable for weeding out low-quality candidates. After all, if an applicant doesn’t take the time to read your content, is he really the best fit for the job?

Content humanizes your brand; it provides a window into the soul of your company, and when your key employees have a voice, you can have big wins.

Universities Cater to a New Demographic: Boomers

During his years at the University of Virginia, Jerry Reid was, for the most part, a typical busy member of the Class of 2014. He worked hard in his classes, joined a fraternity, was a member of the debating society, played flag football, and cheered for school sports teams.

But in one significant way, Reid was far from typical: He enrolled in college at the age of 66, receiving his bachelor’s degree this spring at 70. “I have become the man that I always wanted to be,” the triumphant new graduate told CBS News.

While few of his peers are likely to replicate Reid’s traditional college journey, a growing number of older Americans are arriving on campuses around the country. Their goal is not to turn back the clock but rather to get help navigating what is fast becoming one of life’s most significant transitions: moving from the hectic middle years into the lengthy new chapter that now precedes old age.

Along with confronting questions about what they’ll do next vocationally, these individuals face fundamental questions about who they’ll be. Contemplating the possibility of 25 years or more of health and engagement, many in their 50s, 60s, and even 70s are searching both for a new sense of purpose and strategies for moving forward.

This would come as no surprise to the great psychologist Carl Jung, who envisioned just such an expansion of higher education more than three quarters of a century ago. Writing about “the stages of life” in the early 1930s, Jung argued that we need schools to prepare people in their middle years for something approximating true maturity. He concluded, powerfully, “we cannot live the afternoon of life according to the programme of life’s morning: for what was great in the morning will be little at evening, and what in the morning was true will at evening have become a lie.”

It’s taken decades, but universities are finally answering this call. Among those leading the way are Rosabeth Moss Kanter and colleagues at Harvard, who in 2005 sounded the call for a “third-stage of education.” By this, they meant something beyond undergraduate and graduate/professional studies—and distinct from much of the fare that goes under the banner of lifelong learning for seniors. With a new phase of life taking shape in the years beyond midlife, they made a compelling case that such an invention would “give higher education a transformational concept and a catalytic innovation” to meet the needs of a population living longer, healthier and potentially more productive lives than ever before in history.

Not content with articulating a powerful vision, Kanter spearheaded Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative (ALI), now enrolling its seventh cohort. ALI targets successful and experienced leaders eager to use their accumulated know-how to address large social problems in a systemic way.

The latest trailblazer in this arena is Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute (DCI), designed to give accomplished leaders the opportunity to lay the groundwork for the next stage of their personal and professional journey—a “path to a new calling”–as they explore ways to translate talents, skills, and experience into efforts designed to create a better world. The program, which launches in January 2015, will begin with 20 participants, who will have access to faculty scholars, classes, and other campus programs as well as each other. It will also emphasize personal health and wellness, reflecting the background of its founder, former Stanford Medical School Dean, Philip Pizzo, MD, now a professor of pediatrics at the university.

While both the Harvard and Stanford programs target elite audiences, it’s important to recognize that they are responding to universal needs for new routes, and rites, of passage into the second half of life. Notably, both are premised on the understanding that adults making this transition are, for the most part, hungry for more than intellectual stimulation or even career retooling alone. They are looking for a cohort and a community during a momentous shift, one that is developmental in nature and often entails rethinking both identity and priorities. These individuals need adequate time and a secure zone to go from one mindset to another, while preparing for a period that could last as long as the middle years in duration and be just as significant.

As millions of Boomers move into a stage that has no name, no clear role in society, yet vast possibilities, there is an urgent need for democratized versions of such programs—offered at a cost within reach of the bulk of the population and widely available through continuing education programs or even community colleges around the country. These pathways might be funded through something akin to the GI bill, which drove higher education to open its doors to a new population during another time of demographic upheaval, as returning soldiers moved from military to civilian life. We could even jumpstart this approach by putting resources in the hands of a new group of older students through allowing those in their 50s or early 60s to take a year or two of “advance” Social Security to fund returning to school, so long as they agree to defer beginning their full benefits until an actuarially-neutral later date.

However funded, developing a robust version of school for the second half of life would not only be good for gray-haired set; it is aligned with the interests of the nation’s higher education institutions and society itself.

The vast group of Americans over 50 comprise an entirely new higher education market, one akin to the growing number of international students who have transformed the population on campuses over the past decade. And enabling their transition in ways exemplified by the Harvard and Stanford programs is also in line with the highest purpose of education—training for citizenship and public good.

With 10,000 Boomers a day moving into the afternoon of life, isn’t it time that we rose to the occasion and came up with a new kind of education for this rapidly emerging, uniquely rich, yet still uncharted, chapter in American lives?

Sometimes, Employees Are Right to Worry About Taking Vacation

According to one study, 13% of managers are less likely to promote workers who take all of their vacation time; according to another, employees who take less than their full vacations earn 2.8% more in the subsequent year than their peers who took all of their allotted days, reports the Wall Street Journal. Thus it’s not surprising that 15% of U.S. employees who are entitled to paid vacation time haven’t used any of it in the past year.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers