Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1375

August 28, 2014

Market Basket’s Employees Were More Important Than Its Shareholders

Over the past half century, the question of who’s really in charge at a corporation has come to receive a pretty simple answer. It’s the shareholders, of course. They’re the ones who bear the residual risk of corporate actions, so they should get final say. Any theory of corporate governance that assigns roles to other stakeholders such as customers or employees has been vulnerable to the criticism that it’s too complicated to work. If corporate executives are agents, they need a principal to answer to. And the way to make this principal-agent relationship work, some very smart people have argued, is to keep it simple and let shareholders reign supreme.

The world we actually live in, though, is a lot messier than that. And now, a couple of months after the majority shareholders of Market Basket, the New England grocery chain that inspires a strangely fervent following, decided that they needed to throw out the long-time chief executive, it appears that the shareholders have lost and the chief executive, the employees, and the customers have won.

It took $550 million in financing from a private equity firm to close the deal, The Boston Globe reported, so it’s not as if financial interests aren’t going to have a say in the company’s future. But with employees and customers staying away after CEO Arthur T. Demoulas was ousted by his cousin Arthur S. Demoulas and other shareholders, it became clear that majority ownership wasn’t entirely the same thing as control. Now Arthur T. is back in the saddle, and he clearly owes this status to forces other than shareholder rights.

Market Basket and other corporations are in fact a mix of interests and rights and responsibilities. And it’s probably correct to argue, as Matthew Bodie of the St. Louis University School of Law has, that employees have for too long been getting short shrift in both academic theory and corporate practice. They bear a lot of risk, too, and perform services that go way beyond what most shareholders provide. At Market Basket the employees were, as Zeynep Ton wrote a few weeks ago, the true stewards of the company’s values and culture. And when they decided en masse not to obey the commands of the shareholder majority, that shareholder majority found itself to be not quite as supreme as it thought.

As a family business where ownership was split 50.5% to 49.5% between the warring factions, Market Basket is a unique case. But it is at least a hint that what has become the standard view of rights and power at corporations is deeply flawed.

How the Internet Saved Handmade Goods

A recent article in The Economist, citing the work of Ryan Raffaelli at Harvard Business School, points to what it calls a “paradox” in the aftermath of disruptive innovation. Some old technologies, after being rendered obsolete by better and cheaper alternatives (indeed even after whole industries based on them have been decimated), manage to “re-emerge” to the point that they sustain healthy businesses. Think mechanical Swiss watches, now enjoying strong sales. Or fountain pens, or vinyl records. Or small-batch, handmade goods — from vermouth to chocolate to pickles.

We could add our own favorite example: pinball. In our HBR article “Big Bang Disruption”, we describe the devastation of arcade pinball machines wrought in only a few years by Sony’s PlayStation home video console. From a historic high in 1993 of 130,000 machines sold, sales fell over 90% in the next five years. By the end of the decade, only one producer—Stern Pinball—was left making new machines, and with arcades closing daily, it looked as if it, too, would soon be facing game over.

But Stern found salvation in a new customer segment of aging baby-boomers who wanted arcade machines for home rec rooms and man caves. Today, the company does roughly $50 million in total sales, with the home market accounting for over 80% of them.

That’s a healthy company. Yet the industry will always remain a shadow of its former self, even as the products that disrupted pinball have revenues in the billions. This is typical of the stage of Big Bang Disruption we refer to as “Entropy,” when the supply chain supporting products and services displaced by a disruptive innovation collapse into a kind of economic black hole. Consolidation shrinks the market down, often to one remaining, integrated producer, who can still profit by serving a small group of legacy customers.

That vestiges of old technologies linger on, capable of being resurrected into viable businesses again, doesn’t seem strange to us. Indeed, it’s part and parcel of the digital disruption remaking every aspect of the global economy. The very technologies that likely disrupted the legacy industry in the first place are the same ones devoted practitioners are using to forge new supply chains and digital platforms for a more efficient, better connected version of the old market. The same disruption is driving both the decline and, later, the re-emergence. There is no paradox.

Consider the re-emergence of artisanal goods. No doubt you are aware of the explosion of the market – some call it a movement – in handcrafted products. At times, it seems, the borough of Brooklyn has become one giant artist colony, with everyone working on something—whiskey, woodworking tools, the reinvention of the egg cream—targeted to a small but impassioned fan-base.

Who are these makers if not the revivers of dying or, in some cases, long extinct technologies? Yet it’s thanks to new digital tools such as Etsy, an Internet marketplace selling hand-made goods from around the world; and Kickstarter, the “crowdfunding” site that mediates donation-based funding for a range of products and services, that these artisans can now find and serve their tiny, global markets of customers. These are segments that would have been impossible for individual artisans to organize in a cost-effective way before the rise of the Internet and electronic communication tools that cut out expensive middlemen and asset-heavy enterprises.

The growth of Etsy, fast becoming the leading storefront for handmade products, shows how small products can generate a big bang. Similar to eBay, it provides a platform and marketplace tools to connect buyers and sellers, including digital storefronts and buyer-seller rating systems to establish all-important virtual reputations.

Etsy charges a 20-cent listing fee per item and takes a 3.5% cut of sales. Since achieving first-year sales of $175,000 in 2006, it has increased that number by four orders of magnitude: in 2013, Etsy sold $1.35 billion in merchandise. A survey of its 5,500 U.S.-based sellers revealed that 88% are women, nearly all working from home. For a fifth of them, selling through Etsy is a full-time job.

And digital capabilities also benefit the production, not just the distribution, of Etsy’s goods. Etsy’s creators benefit from global markets for sourcing raw materials, for example. Other small-scale sellers benefit from more affordable web hosting, design, and manufacturing, all of which are fueling much of the growth in cost-effective handmade and customized goods and services.

Thus, artisanal soap-making has grown from just a handful of producers in 1986 to over 150, most in Oregon, who now have their own trade association. Much of that growth was made possible thanks to Etsy, where handmade soap represents over 5% of all products being offered on the site.

The point is not that most consumers will ever care enough to choose soap that is made with goat’s milk, or lard, or without any animal product. On the contrary, the point is that it isn’t necessary for most consumers to do so. With handmade soap selling for $4-6 a bar, while mass-produced soap retails for about $1, sellers can do fine with small, loyal customer bases.

Meanwhile, crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter are solving the most difficult problem facing small businesses and sole proprietors whose ideas require substantial upfront investment—raising the necessary capital. In 2013 alone, Kickstarter users funded nearly 20,000 projects and committed nearly $500 million.

Among these are thousands of projects posted by producers of art, crafts, design, fashion, and food–including a recent campaign that raised $55,000 for potato salad (don’t ask). Together, artisanal categories account for at least 20% of all Kickstarter campaigns and over $100 million in user donations.

The Economist sees these developments as a rejection of the disruptors. “[T]he more that disruptive innovations like the internet boost the overall productivity of the economy,” they write, “the more room there will be for old-fashioned industries that focus on quality rather than quantity and heritage rather than novelty.” But the Japanese artisan offering hand-tooled wooden ballpoint pens to willing buyers around the world uses the same digital tools that make possible low-cost retractable gel-ink pens.

And the performance breakthroughs achieved by disruptive technologies aren’t the only ones by which consumers choose. Hand-crafted or artisanal goods might look better, last longer, and outperform mass-produced goods, at least for particular uses or users.

A digital smart watch keeps time more accurately than a finely-crafted Patek Phillipe, but the latter performs in other ways. As The Economist notes, “people do not just buy something because it provides the most efficient solution to a problem. They buy it because it provides aesthetic satisfaction—a beautiful book, for example, or a perfectly made shirt—or because it makes them feel good about themselves.”

Nostalgic goods. Artisanal goods. Disrupted technology goods. Each of these are businesses whose customers are devoted, but few and far between. Fortunately, in the digital age we can have our Turkish Taffy and eat it, too. Today’s rich trade in heritage goods is happening because of disruptive technologies, not in spite of them.

Reclaiming Your Turf After Maternity Leave

We’d all like to believe that when we return from maternity leave, our bosses, colleagues and subordinates will welcome us back, and maybe even demonstrate some patience and supportiveness. Unfortunately, that’s not always what goes down. Too often, bosses are insufficiently empathic and organizations do not provide enough flexibility. However, in my own experience, both as a new mother in the corporate world, and as an executive coach who has worked with women who are ascending to senior leadership positions over the last twenty years, I have found that it is peer relationships that are often the toughest to navigate.

There are ample guidelines out there on how to ask your boss for more flexible hours, but a shortage of advice on how to handle a peer who – having covered for you during your leave – won’t give you back your turf.

This is precisely the situation Shannon, an advisor at a financial services company, faced when she returned from leave. A male coworker, her peer, had gotten close to her key investors while she was away. But upon her return, instead of relinquishing her accounts, he demanded to be cc’d on everything, withheld information from her, and left Shannon’s name off of client offering memos. He began to assume a supervisory role and attitude toward her, which she deeply resented. Shannon considered her options—confront the coworker? Or go over his head to the boss? She didn’t want to be seen as the one sinking into petty politics. When she finally confronted him, he denied any wrongdoing, saying he was just trying to do what was best for the company. Shannon wondered whether she had inadvertently made a bad situation worse, by revealing her weakness and anxiety to a rival who she did not doubt would use this knowledge to further weaken her.

Whether you’re dealing with an untrustworthy rival like Shannon’s or simply a coworker who has gotten used to doing things her way – and seems to be having trouble relinquishing your own duties back to you — it’s important to strategically manage your re-entry, beginning with what you do even before you leave.

Start by thinking strategically about your short and long-term career goals, as well as your team’s needs. Sometimes a maternity leave presents an opportunity to hand off responsibilities that could help develop more junior colleagues, or a useful excuse to identify tasks to be outsourced or dropped entirely.

Before you leave, meet with your boss to discuss expectations and goals for your return. Your boss can help your peers understand that they will only be covering for you temporarily.

Immediately before your return, set up a call with your manager and relevant peers to learn about any possible changes to your agreed-upon re-entry plan, and meet with them early after your return so you are fully up to date and can approach your “on ramp” back to work with the latest information about what peers are doing and where projects stand. Work with your colleagues and boss on a timeline for taking over your old projects.

Before, during, and after your return, be sure to thank the coworkers who have taken on parts of your job. The reality is that they have had extra work to do, and often their efforts are not rewarded by the organization. Let them know that you acknowledge their assistance and will endeavor to reciprocate someday.

These measures should help mitigate conflict before it starts, but if there is conflict with a coworker, weigh the pros and cons of a direct confrontation. If you decide to confront, plan the conversation carefully and get some help in preparing from a trusted friend or supporter. Be clear with yourself regarding what you are trying to accomplish– Are you trying to put him on notice? Ask her to back off? First seek to understand his or her point of view, and start from a place of inquiry instead of from a place of acting threatened and defensive. Carefully consider bringing the situation to your boss.

In Shannon’s case, she realized that the rivalry had become a proxy for all her new-mother ambivalence and emotions about life and work. She also knew that she had made a good faith effort to constructively engage with her competitive peer, but that her efforts had not been successful and therefore, escalation to her boss was necessary. However, before she met with her boss, she was careful to separate out her feelings of anger and betrayal from the outcome she wanted: control of her own clients. She requested that her boss go to her rival to thank him for helping while Shannon was out, but also asked that he firmly remind him that Shannon would now be handling her own accounts again. While Shannon’s relationship with her rival is still strained, she is hopeful that her boss will deliver, in word and deed, on the explicit and implicit promises he made before she went on maternity leave.

The Real Reason Companies Are Spending Less on Tech

After the dot-com bubble, investment in software and information processing equipment in the U.S. tumbled, and stayed down. As a percentage of GDP, it’s now back to mid-1990s levels:

There’s a version of the chart above in the much-discussed paper that MIT economist David Autor presented last week at the Federal Reserve’s annual Jackson Hole meeting. As part of a thoughtful and generally sanguine look at whether machines are going to take all of our jobs, Autor wrote that whatever might happen in the future, computers and their robot friends didn’t seem to be taking our jobs now:

As documented in [the chart] the onset of the weak U.S. labor market of the 2000s coincided with a sharp deceleration in computer investment — a fact that appears first-order inconsistent with the onset of a new era of capital-labor substitution.

Autor suggested that financial-market troubles (first the dot-com bust, then the global financial crisis) coupled with “China’s rapid rise to a premier manufacturing exporter” probably played much bigger roles in U.S. job market troubles of the past decade than new technology had. That seems reasonable enough.

But I couldn’t help but fixate on that information-technology chart, which seemed to show corporate America giving up on IT. Maybe it was Nick Carr’s famous May 2003 HBR article “IT Doesn’t Matter” that did it. Or maybe corporate executives found that all that money they were pouring into computers wasn’t really paying off, or that even if it did, stock buybacks were an easier and safer path to keeping their paychecks big.

Or maybe modern information technology just keeps getting cheaper.

The software and devices of today can do vastly more than those of a decade ago, usually for the same or lower prices. The Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis try to adjust for such quality changes in calculating inflation and real GDP. They catch some flak for this from those who think they are understating inflation, but it seems like a necessary exercise, especially in IT. So I set about redoing the above chart using the “chained-dollar” inflation-and-deflation-adjusted versions of both GDP and investment in information technology equipment and software. I could only easily access data back to 1999, and I should note that the BEA explicitly cautions users of its data against doing what I did, “because the prices used as weights in the chained-dollar calculations usually differ from the prices in the reference period, and the resulting chained-dollar values for detailed GDP components usually do not sum to the chained-dollar estimate of GDP or to any intermediate aggregate.”

Got that? Anyway, here’s the chart:

So despite small drops amid the dot-com bust and the financial crisis, real investment in information technology has continued to rise. Well, sort of. The amount of money corporations have been putting into IT, relative to the size of the overall economy, dropped sharply in the early 2000s and has stayed down (that’s what the first chart shows). But the estimated value that they’ve been getting out of those investments has continued to rise.

I don’t think this chart helps a lot in answering whether the machines will take our jobs. The two charts together, though, do illuminate much about the strange economy of the past decade-plus.

Corporations have been spending relatively less on IT and getting dramatically more for the money. Their biggest area of capital investment, thus, has been something of a free lunch. The result: big profits, low capital spending, and big piles of cash that executives and boards don’t quite know what to do with.

You might think that the ever-bigger bang for the buck in IT would lead corporate managers to double down and invest even more, but as Clayton Christensen and Derek van Bever argued in the recent HBR article “The Capitalist’s Dilemma,” a variety of financial pressures are pushing them to focus on efficiency and performance improvement rather than investing in innovations that might create new markets.

The pace of improvement in IT is a giant gift that, since the early 2000s, only a few have been rushing to open.

What Baseball Fans Really Love: Doubt About the Outcome

In major league baseball’s first half-century, game attendance was entirely determined by teams’ winning percentages, but in recent decades fans have been increasingly attracted by stadium quality, batting performance, and outcome uncertainty, raising the importance of competition-enhancing policies such as player free agency, say Seung C. Ahn of Arizona State University and Young H. Lee of Sogang University in South Korea. When a league policy enhances competitive balance enough to increase doubt about game outcomes and about consecutive-season dominance by 1 standard deviation, attendance increases by 4% in the American League and 7% in the National League.

Score a Meeting with Just About Anyone

We’re all inundated with meeting requests these days. It’s easy to say no to the egregious ones, like the stranger who recently emailed me to suggest that I meet with him on a specific date so I could provide him with free career coaching. But — though I know better than to ask for pro bono resume critiques — I’ve certainly been on the other side of the equation at various times, having my meeting requests turned down or ignored altogether. In fact, most of us probably have; in an increasingly time-pressed world, almost no one has the leisure to connect “just because.” Here are the strategies I’ve learned over time to ensure the people I want to meet are more likely to say yes.

Recognize where you’re starting. A good friend can easily drop you a line letting you know they’ll be in your city and suggesting a meetup. “You can write with a presumptive tone at certain levels of intimacy,” Keith Ferrazzi, the author of the networking classic Never Eat Alone, told me during a recent interview. “But you have to lead with certain degrees of currency when you don’t have that level of intimacy.” In other words, strangers should never presume that the other person wants to connect with them — that fact needs to be established first. So in your initial message, you need to give them a good reason (the “currency” that Ferrazzi mentions), which could be anything from a PR opportunity (such as interviewing them for your blog) to something you can teach them (how to improve their search engine optimization) to the opportunity to connect with another guest they want to meet at your dinner party. Make clear the value proposition of getting to know you; otherwise, it’s far too easy for them to underestimate you and assume you don’t have anything to offer.

Start with a modest ask. An hour or a half-hour doesn’t seem like a lot of time. But if you’re one of 20 or 50 requests that week — which isn’t an uncommon number for busy professionals to receive — it can quickly become overwhelming. So don’t ask to meet for lunch; aim smaller, so it’s easy to say yes (a strategy I describe in “How to Land an Interview with a Cold Call”). I recently agreed to a phone conversation with one aspiring author who vowed in his email, “You must have a full schedule, so I will get to the point quickly and can keep the call to less than 10 minutes.” In the end, I didn’t speak with the author for 10 minutes; our call, which proved to be engaging, lasted 30 — despite the fact that I likely would have rejected a request for that amount of time. That’s the same strategy that well-known psychologist Robert Cialdini discovered in his early research on door-to-door fundraising campaigns for the United Way. Adding five words to the standard pitch — “even a penny would help” — doubled contributions. “Because how can you say no if even a penny is acceptable?” Cialdini told me in an interview for my forthcoming book. “We doubled the number of people who gave and no one [actually] gave a penny. You don’t give a penny to United Way; you give a donation that’s appropriate.”

Always find a warm lead. No matter how successful you are professionally, there are always going to be some people you’d like to meet that haven’t yet heard of you. The challenge is to break through and ensure they view you as a colleague — someone “like them” — rather than a stranger impinging on their time. Finding mutual contacts is one of the best ways to do it. Even Ferrazzi, known for his networking prowess, still has “aspirational contacts” he’d like to meet. In those cases, he says, “I leverage others to help with outreach.” Facebook, with its “mutual friends” function, makes this simple; LinkedIn — which charts connections out to the second and third degree — makes it even easier. Having shared contacts introduce you puts you on peer footing and gets your relationship off to the right start.

Just as sitting is apparently the new smoking, time is the new money. No one can afford to give it away carelessly these days. If you’re asking someone you don’t know for a half-hour, or even 10 minutes, you have to think of your request like you’re making a VC pitch. Why should they speak to you? How can you establish your credibility upfront? How will it benefit them? How can you pack the greatest ROI into the shortest time? If you can answer those questions well, you should be able to get a meeting with just about anyone.

August 27, 2014

Do Your Company’s Incentives Reward Bad Behavior?

The current lull in the sparring between General Motors and Congress provides a great opportunity to look at what wasn’t discussed in the furor over the company’s recent recalls and its admitted slip-ups in auto safety: namely, rewards and punishments.

For example, during CEO Mary Barra’s testimony in Washington, few lawmakers seemed interested in exactly how GM plans to change its processes, and Barra, while acknowledging that the company needs to improve safety procedures, made it clear that the company won’t share the data from its internal investigation of ignition-switch defects.

But Barra, as well as Congress and everyone who drives a GM vehicle, should be more curious about which behaviors in the deepest layers of the company are being rewarded and punished.

A report by former federal prosecutor Anton R. Valukas provides a hint: Although managers’ bonuses are based partly on vehicle-quality improvements, and safety is supposed to be paramount, cost is “everything” at GM, and the company’s atmosphere probably discouraged individuals from raising safety concerns. Earlier this summer, a former GM manager described a workplace in which the mention of any problems was unacceptable.

It should go without saying that the best way to get the behaviors you want is to provide rewards for doing them, or at least refrain from punishing people for doing them. The flip side is that you have to make sure you’re not inadvertently providing rewards for behaviors you’re trying to discourage.

In order to properly align its incentives to support its mission and objectives, a company must determine what managers and employees believe they are being encouraged to do and not do. Collecting this information is a three-step process.

First, make a list of behaviors you want more of and a list of behaviors you don’t want. The importance of responding honestly to this assignment cannot be overstated. For example, you may say you want a culture of quality, safety, and transparency, but do you really? Or do you believe that this is an unattainable, unaffordable goal in view of the financial and operational challenges your organization currently faces?

Next, make a list of the behaviors you are currently measuring. Don’t concern yourself at this point with whether your measurements are objective or subjective or whether they’re included in your annual performance reviews. Then compare each of the behaviors on your “more of” and “less of” lists to the list of behaviors you’re currently measuring. Put a circle around the behaviors you are not now measuring. This is your danger list! If a behavior you care about is not being measured:

Your employees are likely to conclude that it isn’t very important, and will act accordingly.

You aren’t able to provide skills training (in cases where the problem results from poor skills rather than low motivation).

You aren’t able to provide feedback about the behavior, either informally or in performance reviews, so how can people improve their performance even if they want to?

You aren’t able to reward the people who are doing what you want. Nor can you penalize people who are not doing what you want.

Some people will do what you want anyway, for personal reasons, but effective leaders create cultures that inspire and motivate people to do the right things. Effective leaders don’t sit idly by while hoping their people will behave ethically and perform competently. And they most certainly do not create or permit the existence of cultures that encourage and reward bad behavior.

Once you have ascertained that the behaviors you care about are being measured and discussed in performance reviews, the third step is to determine whether your rewards and penalties support your espoused values. Specifically, with regard to each item on your “more of” and “less of” lists, ask your employees what would be most likely to happen to them if they engaged in that behavior. Offer four possible answers: “I’d be rewarded or approved,” “I’d be punished or discouraged in some way,” “There would be no reaction of any kind,” or “I wouldn’t know what to expect.”

If GM were to engage in this exercise it would be important for the company to look at the fit between its incentives and its long-term goals — particularly those relating to such desired “more of” behaviors as preventing the types of errors that caused the ignition-switch crisis, behaviors aimed at early detection of errors, and behaviors aimed at immediate communication of any errors that are discovered.

Does GM’s reward system dispense incentives for cost controls even to the detriment of product safety? Does it discourage employees from acting on their awareness of problems? These are important questions that senior management should be investigating.

It’s important, also, for companies to take note of the organizational level of each respondent in its surveys. Research shows that employee perceptions of rewards systems tend to degrade as you go lower in the organization. People in executive positions are more likely than those at the bottom to feel they’d be rewarded, or at least not punished, for raising uncomfortable issues.

But even at the top, it can be difficult to speak up. At GE, Jack Welch sincerely wanted to hear the truth — he hated it when people brought him sugar-coated information. Yet when managers described systems going awry or other kinds of problems, his disappointment, frustration, and rapid-fire, penetrating questions could be quite intimidating.

The few public discussions about GM’s internal processes around quality have been vague and tinged with the language of moral breakdown. Barra told GM shareholders that employees are now pledging to be vigilant. Jesse Jackson, addressing the board, said “we are in this crisis because of a lack of integrity and courage.”

But Jackson’s assertion seems to me to inaccurately define the problem. If GM desires a culture that gives priority to such things as product quality, safety, transparency, and integrity, why is courage required to behave in ways that are consistent with these values? Shouldn’t it be the other way around? Surely it doesn’t require courage to give one’s boss, senior management, and the CEO what they truly want.

Curiosity Is as Important as Intelligence

There seems to be wide support for the idea that we are living in an “age of complexity”, which implies that the world has never been more intricate. This idea is based on the rapid pace of technological changes, and the vast amount of information that we are generating (the two are related). Yet consider that philosophers like Leibniz (17th century) and Diderot (18th century) were already complaining about information overload. The “horrible mass of books” they referred to may have represented only a tiny portion of what we know today, but much of what we know today will be equally insignificant to future generations.

In any event, the relative complexity of different eras is of little matter to the person who is simply struggling to cope with it in everyday life. So perhaps the right question is not “Is this era more complex?” but “Why are some people more able to manage complexity?” Although complexity is context-dependent, it is also determined by a person’s disposition. In particular, there are three key psychological qualities that enhance our ability to manage complexity:

1. IQ: As most people know, IQ stands for intellectual quotient and refers to mental ability. What fewer people know, or like to accept, is that IQ does affect a wide range of real-world outcomes, such as job performance and objective career success. The main reason is that higher levels of IQ enable people to learn and solve novel problems faster. At face value, IQ tests seem quite abstract, mathematical, and disconnected from everyday life problems, yet they are a powerful tool to predict our ability to manage complexity. In fact, IQ is a much stronger predictor of performance on complex tasks than on simple ones.

Complex environments are richer in information, which creates more cognitive load and demands more brainpower or deliberate thinking from us; we cannot navigate them in autopilot (or Kahneman’s system 1 thinking). IQ is a measure of that brainpower, just like megabytes or processing speed are a measure of the operations a computer can perform, and at what speed. Unsurprisingly, there is a substantial correlation between IQ and working memory, our mental capacity for handling multiple pieces of temporary information at once. Try memorizing a phone number while asking someone for directions and remembering your shopping list, and you will get a good sense of your IQ. (Unfortunately, research shows that working memory training does not enhance our long-term ability to deal with complexity, though some evidence suggests that it delays mental decline in older people, as per the “use it or lose it” theory.)

2) EQ: EQ stands for emotional quotient and concerns our ability to perceive, control, and express emotions. EQ relates to complexity management in three main ways. First, individuals with higher EQ are less susceptible to stress and anxiety. Since complex situations are resourceful and demanding, they are likely to induce pressure and stress, but high EQ acts as a buffer. Second, EQ is a key ingredient of interpersonal skills, which means that people with higher EQ are better equipped to navigate complex organizational politics and advance in their careers. Indeed, even in today’s hyper-connected world what most employers look for is not technical expertise, but soft skills, especially when it comes to management and leadership roles. Third, people with higher EQ tend to be more entrepreneurial, so they are more proactive at exploiting opportunities, taking risks, and turning creative ideas into actual innovations. All this makes EQ an important quality for adapting to uncertain, unpredictable, and complex environments.

3) CQ: CQ stands for curiosity quotient and concerns having a hungry mind. People with higher CQ are more inquisitive and open to new experiences. They find novelty exciting and are quickly bored with routine. They tend to generate many original ideas and are counter-conformist. It has not been as deeply studied as EQ and IQ, but there’s some evidence to suggest it is just as important when it comes to managing complexity in two major ways. First, individuals with higher CQ are generally more tolerant of ambiguity. This nuanced, sophisticated, subtle thinking style defines the very essence of complexity. Second, CQ leads to higher levels of intellectual investment and knowledge acquisition over time, especially in formal domains of education, such as science and art (note: this is of course different from IQ’s measurement of raw intellectual horsepower). Knowledge and expertise, much like experience, translate complex situations into familiar ones, so CQ is the ultimate tool to produce simple solutions for complex problems.

Although IQ is hard to coach, EQ and CQ can be developed. As Albert Einstein famously said: ““I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.”

Who’s Being Left Out on Your Team?

Feeling left out or ignored at work can have tremendously negative effects on workers’ well-being. In a recent survey, researchers at the University of Ottawa found that workplace ostracism does greater harm to employees’ happiness than outright harassment. But what does feeling “included” at work even mean? And how can managers foster an environment where all employees — regardless of age, race, gender, or personality type — feel valued?

What the Experts Say

Creating a workplace where employees feel included is directly connected to worker retention and growth, says Jeanine Prime, leader of the Catalyst Research Center for Advancing Leader Effectiveness. Yet many corporate diversity programs focus more on creating a diverse workforce, and too little on the harder job of fostering inclusion. Prime’s organization recently completed a survey of 1,500 workers in six countries that showed people feel included when they “simultaneously feel that they both belong, but also that they are unique,” Prime says. When managers can achieve that balance, the business benefits are profound. Employees who feel included are “much more productive, their performance is higher, they are more loyal, they are more trustworthy, and they work harder,” says Christine Riordan, provost and professor of management at the University of Kentucky. Here’s how to foster more inclusion on your team.

Set an example

Inclusive attitudes start at the top. “Most people are blind to the everyday moments that leave others feeling excluded,” says Prime. Managers should take care to constantly examine their biases and behaviors. Be on the look out for what Riordan calls “micro inequities,” which occur when people are treated differently — whether it’s overlooked, avoided, or ignored — by yourself or others. As an example, Riordan cites a woman who complained recently that when she stood with other colleagues in a group, a male colleague only shook hands with the other men. It might be an inadvertent omission, but the woman still felt excluded. “Leaders have to recognize those micro inequities in themselves and others and work to correct them,” says Riordan.

Don’t diminish differences

Helping people feel that they belong isn’t the same as making them feel interchangeable. Employees want their managers to recognize and value their uniqueness, says Prime, and that means acknowledging “the distinct talents and perspectives they bring to the table.” Leaders might want to say that they are blind to race or gender or sexual orientation, but that attitude can prevent them from seeing instances of ostracism, as well as the unique perspectives that employees can bring to problem-solving and innovation. “If you say you don’t see gender, then you might not recognize when woman scientists don’t get mentored or aren’t invited onto research projects,” says Riordan. Don’t assume that people want their differences erased in order to be part of the group.

Share the spotlight

According to Catalyst’s survey, leaders who support their employees’ development are more likely to foster a sense of inclusion. For instance, suggesting that employees rotate as meeting leaders might help an untested employee showcase her value to others. Handing some management responsibilities for a new project to a more introverted worker might help build his confidence and give him facetime with others. “Anything a manager can do to create a positive message that every person is valued and has equal access in that group is a good thing,” says Riordan.

Seek input

One simple way to make employees feel more included, particularly if they are more introverted, is to ask for their input and opinions in front of others. Listening to employees not only signals to them that you value their contributions, but also demonstrates to other employees that everyone has value. Plus, you get the added benefit of a diverse set of opinions. “Inclusive leaders do a good job of drawing out the unique perspectives of different followers and engaging with those different points of view,” says Prime. If an individual still has trouble speaking up or gets interrupted or talked over, keep offering her the floor, and don’t be stingy with deserved praise.

Keep at it

Fostering inclusion is an ongoing process. “Being inclusive is not a ‘check the box’ activity,” says Prime. “It’s a way of being, and you never stop working at it.” Changing practices to incorporate inclusive policies and behaviors can be difficult, but creating an environment where everyone feels they can speak up will only result in better business outcomes. Managers “have to be proactive,” says Riordan, because when they are, employees will work more effectively, and your business will reap the rewards.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Check your own behavior and biases for tendencies that might make people feel excluded

Empower others — it makes them feel trusted and included

Continually work at creating an inclusive culture — it’s an ongoing process

Don’t:

Gloss over differences — people want their unique contributions to be valued

Assume diversity is the same as inclusion

Leave it to chance — be proactive about promoting inclusion

Case study #1: Foster interactions

Carol* had been working at a real estate firm in Minneapolis for a year, attending nearly every meeting but rarely speaking up. Because she was more introverted than her colleagues, she was “completely ignored by the other agents,” says Andrew Thompson, a business consultant who had been hired to help the firm with strategy. However, her sales record suggested that “she had clear potential,” and the lead broker made it his mission to help her feel more included.

To get Carol out of her shell and to foster office inclusion more generally, the lead broker and Andrew launched three initiatives. First, they announced a “professional manners” initiative, ostensibly to improve relations with potential clients. The new policy encouraged “politeness” in the workplace, with everyone advised to interact more often, including saying “good morning” to colleagues. “There was resistance at first,” says Andrew, “but soon everyone was in the habit” of reaching out to at least one other agent each day, with a noticeable improvement in office sociability.

The manager also launched a policy that required each agent to lead the weekly meeting at least once every few months. As part of the meeting leadership duties, each agent was encouraged to present an idea that would make the office or work processes better. And finally, a “lunch companion program” was established with regular, rotating one-on-one lunch partners.

A year later, not only had Carol become a key member of the team, overall office sales had increased by 15%, which the head broker attributed to the atmosphere of unity and improved customer experiences. “What started as a project to rescue a single individual from isolation turned into business and social success for everyone,” Andrew says.

Case study #2: Help people shine

David Schabel was a senior project analyst at an Ohio-based enterprise software company when Robert* was hired as part of an expansion. Robert “came in with a lot of great ideas,” says David, but he was quiet and shy, and didn’t always know how to interact with his mostly Type-A colleagues. As a result, Robert was soon being left out of discussions, meetings, and working dinners, which meant that he was losing out on new assignments and work projects. “We needed to identify how to enable him to succeed,” David says.

David soon realized that one major reason for Robert’s solitude was that he felt out of his depth. “We had hired Robert for a role that didn’t match his skills and interests,” David says, “so he was being brushed aside by coworkers because he couldn’t do what came easily to them.” After several months of meeting Robert for coffee with a handful of other colleagues, David assigned him to a group that focused more on strategic objectives, which he knew would be a better fit based on the conversations they’d had. “Robert truly came alive in this new role,” David says. “Before long, he had assumed the position of managing the group,” and was being included around the office.

By reassigning Robert to a project that better aligned with his skill set, “the organization avoided losing a valuable person and employee,” says David. “We learned to repurpose Robert in a role that maximized not only his personal fulfillment, but also his value to the company.”

*Not their real names

The Problem with Using Personality Tests for Hiring

A decade ago, researchers discovered something that should have opened eyes and raised red flags in the business world.

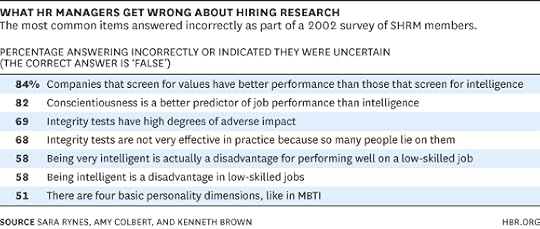

Sara Rynes, Amy Colbert, and Kenneth Brown conducted a study in 2002 to determine whether the beliefs of HR professionals were consistent with established research findings on the effectiveness of various HR practices. They surveyed 1,000 Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) members — HR Managers, Directors, and VPs — with an average of 14 years’ experience.

The results? The area of greatest disconnect was in staffing— one of the lynchpins of HR. This was particularly prevalent in the area of hiring assessments, where more than 50% of respondents were unfamiliar with prevailing research findings.

Several studies since have explored why these research findings have seemingly failed to transfer to HR practitioners. Among the causes are the fact that HR professionals often don’t have time to read the latest research; the research itself is often present with technically complex language and data; and that the prospect of introducing an entirely new screening measure is daunting from multiple angles.

At the same time, anyone who has ever been responsible for hiring, much less managing, employees knows that there is a wide variation in worker performance levels across jobs. Therefore, it is critical for organizations to understand what differences among individuals systematically affect job performance so that the candidates with the greatest probability of success can be hired.

So what are the most effective screening measures?

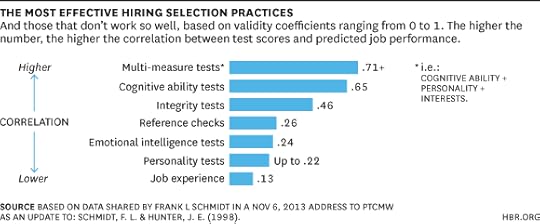

Extensive research has been done on the ability of various hiring methods and measures to actually predict job performance. A seminal work in this area is Frank Schmidt’s meta-analysis of a century’s worth of workplace productivity data, first published in 1998 and recently updated. The table below shows the predictive validity of some commonly used selection practices, sorted from most effective to least effective, according to his latest analysis that was shared at the Personnel Testing Counsel Metropolitan Washington chapter meeting this past November:

So if your hiring process relies primarily on interviews, reference checks, and personality tests, you are choosing to use a process that is significantly less effective than it could be if more effective measures were incorporated.

And yet that’s how many companies operate. According to a 2011 NBC News article, the use of personality assessments are on the rise, growing as much as 20% annually. Especially problematic is the widespread use of Four Quadrant (4-Q) personality tests for hiring, something I see regularly in my consulting work.

A 4-Q assessment is one where the results classify you as some combination of four different options labeled as letters, numbers, colors, animals, etc. They originated around 450 BC when Empedocles noticed that he could group people’s behavior into four categories which he labeled earth, water, fire, and air. Hippocrates made the same observation, but (coming from a medical background) labeled the categories blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Since then, hundreds of iterations of these tools have been developed, all essentially based on the same premise and theory.

Generally speaking, 4-Q tools consist of a list of adjectives from which respondents select words that are most/least like them, and are designed to measure “style,” or tendencies and preferences. While they can seem highly insightful — not to mention being widely available and inexpensive — they have some severe shortcomings when used in high stakes applications such as hiring.

For one, they tend to be highly transparent, enabling a test taker to manipulate the results in a way that they feel will be viewed favorably by the administrator. Also, since they are designed to measure “states” (as opposed to more stable “traits”), there is a significant chance that the results will change over time as the individual’s context changes (most publishers of 4-Q tests recommend that individuals re-take them at fairly frequent intervals for this reason).

This begs the question: How can an individual’s assessment results be used to predict future job performance if there is a reasonable chance that their scores will change over time?

When using any assessment, managers need to step back and ask themselves one basic question before giving it to a potential employee: Is this test predictive of future job performance? In the case of 4-Qs, probably not. They can provide tremendous value for self-discovery, team building, coaching, enhancing communication, and numerous other developmental applications. But due to limited predictive validity, low test-retest reliability, lack of norming and an internal consistency (lie detector) measure, etc., they are not ideal for use in hiring.

The strongest personality assessments to use in a hiring context are ones that possess these attributes:

Measure stable traits that will not tend to change once the candidate has been on the job for some length of time.

Are normative in nature, which allows you to compare one candidate’s scores against another’s to determine which individual possess more (or less) of a particular trait.

Have a “candidness” (or “distortion” or “lie detector”) scale so you understand how likely it is that the results accurately portray the test-taker.

Have high reliability (including test-retest reliability) and have been shown to be valid predictors of job performance.

Even when using a tool that meets the criteria outlined above, personality constructs are not the most predictive measure available. Personality tests are most effective when combined with other measures with higher predictive validity, such as integrity or cognitive ability.

Using well-validated, highly predictive assessment tools can give business owners and managers a significant leg up when trying to select candidates who will become top producers for the organization. However, all assessment approaches are not created equal. And some will not offer a significant return on your investment. Accordingly to a 2014 Aberdeen study [registration required], only 14% of organizations have data to prove the positive business impact of their assessment strategy. Knowing which types of assessments will be most effective in accomplishing the specific objectives you have identified for your organization will enable you to select a tool with a measurable impact on the bottom line.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers