Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1379

August 20, 2014

3 Behaviors That Drive Successful Salespeople

Most people consider selling to be an art rather than a science: some people have it and some people don’t. But this leaves a lot of uncertainty in what is often a company’s most profitable department, and it makes managing a high-functioning sales force notoriously difficult. The prevailing thinking is that the amount of time salespeople spend with customers is the most important determinant of how much they are able to sell. But recent research has uncovered an even more powerful leading indicator: the size and quality of a salesperson’s network inside their own company.

People analytics can help organizations learn more about what behaviors differentiate their most successful salespeople. At VoloMetrix, we recently studied the sales force of a large B2B software company using six quarters of quota attainment data for a several thousand employees. We then correlated it against 18 months of VoloMetrix-created People Analytics key performance indicators. These KPIs measure things like time spent with a customer or manager; the size and cross-functionality of an internal network; how important a given employee is within an internal network; time spent in the presence of senior leadership; and many others calculated anonymously per person.

We expected to have two phases to the study. The first would simply run the model against the entire sales organization without bothering to segment them in any way. This meant that people selling to small- and medium-sized businesses were lumped in equally with people selling through channels and large enterprise, and that Asia-Pacific was lumped into with Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, and everywhere else.

Our researchers assumed that no meaningful correlations would emerge at that level — it seemed obvious that the most effective sellers of simple low-priced items to SMBs in Asia would look quite different than North American seven-figure enterprise solution sellers. That’s why phase two of the study would break employee populations down to these more similar groups and run the analysis again.

We didn’t need the second phase.

It turns out that regardless of what you are selling, who you are selling it to, or where you happen to be in the world, success in selling is highly correlated with three things:

Spending enough time with customers and prospects

Having a large and healthy network in your own organization

Spending time with and getting attention from your manager and other senior people in your own organization

The first factor is trendy, and increasing time with customers is high on the priority list of most sales leaders and consultants. Unfortunately, simply increasing the amount of time your underperforming sellers spend with customers is unlikely to help much, and might actually hurt. Imagine a bad sales person who has tried to sell you something; now imagine spending twice as much time with them.

The second and third are a bit less obvious, but incredibly important.

Enterprise buyers are increasingly sophisticated and enter a sales process fairly well educated about their options. They are looking for someone that is credible, can understand their needs, and can address their questions and concerns quickly and competently. Doing this well requires a seller to be able to get the right people with the right expertise to the right place at the right time. It also requires them to know how to get the deal approved internally, have access to management when needed, and have a holistic understanding of what their entire company can offer to the buyer above and beyond the current transaction.

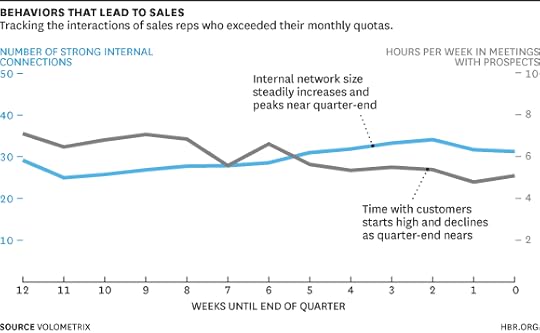

Take this example from the B2B company I described earlier. The top salespeople began the quarter by meeting with prospects. But as time went on, their time spent with customers declined while their internal networks grew.

Underperformers exhibited similar trends, but the numbers were lower — they spent 25% less time with customers throughout, had 20% smaller internal networks, and spent 20% less time with senior-level managers.

To be sure, these characteristics can be hard to measure. But our study, which has been repeated multiple times with similar results, and others like it have proven these network and behavioral metrics to be highly predictive of sales effectiveness.

Even better, these metrics are actionable. Top performing reps typically don’t know what they are doing differently than everyone else, and underperforming reps would prefer to be more successful, but don’t know how. In addition, managers might not understand just how much their interactions (or lack thereof) with employees directly affect sales. Through people analytics metrics, companies can provide transparency up and down their entire go-to-market organization to give employees, managers, and executives a more granular set of ways to measure their activities and, more importantly, prioritize those that lead to success.

I Was a Cyberthreat to My Company. Are You?

It seems like every other day, I receive a notification of yet another update of Adobe Flash Player to install on my computer. At first I thought these messages were merely annoying. But then I realized that they’re also potentially dangerous, after working with the University of Oxford’s David M. Upton and Sadie Creese on their HBR article “The Danger from Within.” My practice of mindlessly installing the updates could have compromised my company’s computer systems.

“Just because the notifications look like they came from Adobe doesn’t mean they did,” Upton told me. “They could be coming from a criminal seeking to install malware on your computer.”

These days all of us should be going to extremes to play it safe. Cyberattacks on organizations are growing exponentially in number, scope, and sophistication. Like many people, I felt horribly vulnerable when I read about the Russian hackers who had stolen 1.2 billion user name and password combinations from companies big and small. So much for my relief that the hackers who stole the credit- and debit-card numbers of some 40 million Target customers didn’t seem to have mine!

What is wildly underappreciated is the fact that a huge number of cyberattacks involve the witting or unwitting assistance of insiders — employees, contract workers, suppliers, distributors, and others who have legitimate access to an organization’s cyberassets. (In the Target case, the weak link was a refrigeration vendor.) Upton and Creese are co-leading an international research project to help organizations uncover and neutralize such threats.

As part of that effort, they have developed this tool to help people assess how much of a threat they pose to their own organizations. Give it a try — it shows how you stack up against others and provides feedback on the precautions that you and your organization are taking against insider threats. You may be surprised by how many common corporate “safeguards” are actually ineffective and how many effective measures are ignored.

The Benefits of Male Small-Talk

In a hypothetical scenario, research participants were willing to pay 6% more for a parcel of land if the male seller engaged in friendly small-talk before negotiating the deal, demonstrating that men benefit from striking up casual conversation before negotiations, says a team led by Brooke Shaughnessy of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Germany. For women, chitchat provides no such effect, though it does no harm. Chitchatting men may benefit from countering male stereotypes of reticence, the researchers suggest.

2% of Your Coworkers Have Face Blindness

If you’re in management, much of your job consists of creating the conditions under which people in the organization can do good work. You work to understand what makes it hard for them to be productive, and help them clear those hurdles. It should interest you, therefore, to know of a challenge that likely affects a percentage of your colleagues, but is rarely acknowledged: face blindness.

Formally called prosopagnosia, face blindness is a cognitive condition characterized by the inability to recognize other people from their faces alone. The condition can be so severe that it affects the recognition of close family members and friends, or even one’s own face. People with face blindness do not have a general lack of knowledge about other people, and can immediately recall what they know about a person once they have realized their identity.

Traditionally face blindness has been reported in a small number of people following brain injury, yet in the last decade it has been revealed that as many as one in 50 people have a developmental form of the condition. These people have never experienced a brain injury or other developmental disorder, and have normal vision. Their difficulties with face recognition seem to extend back to early childhood, and some evidence suggests the condition runs in families.

Some well-known people have been forthcoming about having the condition – such as the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, the artist Chuck Close, and the business investor Duncan Bannatyne – but public awareness of it remains quite low. Thus, most unaffected people take their face recognition skills for granted and it does not occur to them that someone might struggle with this process. Meanwhile, while many with face blindness find ways to cope, many others experience feelings of anxiety, embarrassment, and guilt when they fail to recognize familiar people. Indeed, even those who know themselves to be face blind often choose not to disclose their condition publicly. They might instead simply avoid personal, social, and occupational situations where they would be required to recognize the faces of familiar others.

Begin to imagine the experience of face blindness, and it quickly becomes evident how some workplaces make the challenges greater. For instance, although a person with face blindness may often be able to compensate for their difficulties in office environments where each individual has a fixed position behind a particular desk, they may struggle to recognize colleagues when encountered in an unexpected or generic location, such as at the coffee machine. The use of “hot-desking” is particularly challenging, since it foils most of the compensatory strategies the face blind use to avoid embarrassing misidentification errors. Many face blind people also struggle in meetings, as seating arrangements are seldom pre-planned and location cannot be used as a cue to recognition. Finally, difficulties are exacerbated in occupations where there are fewer non-facial cues to recognition. Think, for example, of workplaces where uniforms are worn. For that matter, men’s business suits offer few distinguishing characteristics to aid person recognition.

Face blindness can also bring about difficulties in interactions with clients. Many people with face blindness worry that they will appear rude, disinterested, or incompetent if they fail to recognize a client upon a second meeting, and believe this may directly influence their performance at work and consequently opportunities for progression or promotion. Some face blind people use clever compensatory strategies to address this issue, such as arriving particularly early for meetings so the client has to approach them, rather than vice versa. However, such strategies are not fool-proof and can still lead to embarrassing failures of identification.

Put all this together and it seems evident that a manager attuned to an individual’s face blindness could make a positive difference to that person’s performance. There hasn’t yet been much research directly focused on the effects of face blindness in the workplace, but one study concluded that the occupational difficulties are potentially as great as those posed by stuttering and dyslexia – conditions for which specific assistance is available.

It is a problem, therefore, that many face blind people are reluctant to disclose their condition at work. This is mostly for fear that employers will not have heard of or understand the condition, or that they will be held back from interactions with key clients and will not be considered for promotion or managerial roles. While laws (such as the Equality Act in the UK) are in place to punish such discrimination, many people fear that low public and professional awareness of face blindness will nevertheless act against them, and, regardless, that even an understanding employer could not assist them with their difficulties.

The fact is that several actions can be taken to assist a face blind colleague. In office environments, free-standing name plates can be displayed on workspaces, and also taken along to meetings to assist with recognition. Colleagues can be advised not to take offence if the person fails to recognize them, and to establish at the start of a conversation that their identity is known. When a face blind employee is required to meet clients or externally-based colleagues away from the office, they may benefit from the presence of another staff member to quietly assist with identifications and introductions.

Finally, it is important to note that, even if a person with face blindness is succeeding in a workplace and does not experience the anxiety and negative consequences described above, there may yet be strong reasons for the condition to be acknowledged. However well an employee copes with their face blindness, in some settings the inability to recognize a face raises health and safety considerations, and it is important that employers think through these implications. Likewise, there are settings in which, if a person’s face blindness were widely disclosed , it might put them at risk – perhaps because they come into contact with vulnerable or potentially threatening populations.

Regardless of the setting, a face blind person should feel able to disclose his or her condition to an employer. There can then be a carefully considered decision about how widely to share this information – and, regardless of disclosure, certain measures can be taken to assist the individual. All of this will happen more as awareness of the condition rises, and managers learn to recognize challenges that have always existed, but to which most of them have been blind.

August 19, 2014

The First Mile: A Launch Manual for Great Ideas

That first mile—where an innovation moves from an idea into the market—is often plagued by failure. In fact, less than 1% of ideas launched inside organizations have any real impact on the bottom line.

The ideas aren’t the problem. It’s the process.

In his new book, The First Mile: A Launch Manual for Getting Great Ideas Into the Market, innovation expert Scott Anthony has created a road map to improve the process and the chances of success. It focuses on the critical moment when an innovator moves from planning to reality, a perilous place where hidden traps and roadblocks slow innovators.

In this interactive Harvard Business Review webinar, Anthony shares his insights and equips innovators with new tools, questions, and examples to speed through this crucial early stage of innovation

What People Are Really Doing When They’re on a Conference Call

If you’re reading this while on a conference call — perhaps even in the loo — you’re not alone. It turns out many U.S. employees would rather do just about anything rather than listen intently to their coworkers from a remote location.

According to InterCall, the world’s largest conference call company — it’s used by 85% of Fortune 100 firms — the percentage of people using mobile phones to dial into conference calls has been rising steadily over the past three years, from 19.4% of all calls in 2011 to 21.2% in 2013.

While this may not be especially surprising — most of your colleagues probably have an iPhone or other such device — the things people do while on conference calls are, well, illuminating. InterCall surveyed 530 Americans to identify some of these activities, 64% of whom said they prefer using a cell phone over a regular old ringer.

And it’s no wonder why. Aside from the convenience, people often find conference calls to be an opportune time to do many, many other things:

And aside from these relatively banal activities (though I might put “go to the restroom” in its own unpleasant category), there are some other, slightly more egregious ones. For example, almost 40% of respondents said they’ve dropped off a call without announcing they’ve done so in order to pretend they stayed on; 27% reported having fallen asleep on at least one occasion; and 13% say they’ve been “outed” for taking a call in a place other than where they claimed.

This segues nicely into the obligatory “some of the stranger places respondents admitted to being while also on the line with their coworkers” section of the survey’s findings:

“In the middle of the woods during a hiking trip”

“Outside while grilling and getting a tan”

“The tunnel leading to NYC”

“A truck stop bathroom”

“McDonald’s Playplace”

“Behind a church during a wedding rehearsal”

“The racetrack”

“DisneyWorld”

“At a pool in Las Vegas”

“Fitting room while trying on clothes”

“The closet of a friend’s house during a party”

“The beach…it was a video call so I kept my tablet up so that my bikini didn’t show”

“Hospital ER”

“Chasing my dog down the street because she got out of the house”

Part of the reason all of this is possible, aside from mobile technology, is the magical mute function — InterCall found that 80% of people surveyed are more likely to mute themselves when using a mobile device rather than landline:

The issue underlying all of this data is that the way we conduct conference calls may not be working particularly well.

For Rob Bellmar, InterCall’s Executive Vice President of Conferencing and Collaboration, the problem is largely about how technology has changed the way we communicate, and thus, the values we attach to it. “Part of the problem comes from too many meetings,” he says. “This leads people to confuse activity with productivity.”

Boredom is not the only reason why we’re so eager to be on email while on a conference call/ “For example,” Bellmar says, “[there's] the decreasing rate of response time that has occurred due to technology making everything more immediate. The new mindset is ‘the first one with the story wins.’ … This immediacy is manifested even more when people work in isolation. They feel compelled to reply when they receive an email or text — whether at their desk or even driving their car. A behavior that didn’t even exist 15 years ago is now pervasive. So it’s no wonder that people multitask while in virtual meetings, whether web-based or audio only.” There are perceived benefits in answering emails as fast as possible.

Tuck Business School Professor Paul Argenti told me that location isn’t really the issue, either. While it’s easy to place blame or poke fun at your colleague who’s taking calls on the beach, “that’s a mistake,” he says. “You can be completely engaged on the beach, in your car, on an airplane. That’s not the variable that matters. If people are distracted, that’s a problem either with the channel choice to begin with, why this person on the call, or the facilitation skills.”

As for the channel question, both Bellmar and Aregenti recommended using video instead of audio.

“Using multi-sensory conferencing tools like web and audio or video creates more engagement and interaction,” says Bellmar. “Video forces people to be more attentive since it is more visible.”

But if you work at one of those organizations that’s still devoted to the speakerphone, there are some practical things you can do to improve meetings, whether you’re the organizer or a participant.

For the organizer, it’s all about the little things. “Make sure all the details are confirmed,” emphasizes Argenti, things like setting up a bridge and making sure every participant has the correct number.

Keith Ferrazzi, the CEO of the consulting firm Ferrazzi Greenlight, suggests that organizers implement a “take 5″ moment at the beginning of each call where, for the first five minutes of the meeting, “everyone should take turns and talk a little about what’s going on in their lives, either personally or professionally.” This, he says, will help break the ice and get people in the mood to actually listen to one another.

He also suggests assigning tasks to different participants tasks — like a minutes recorder and a Q&A manager — to keep everyone tuned in. And, unless there’s excess noise, he advocates for an outright ban of the mute function: “A surefire way to kill the mood of any virtual meeting is with the dead silence that follows a joke because people have their audio on mute,” he writes. “Perhaps more important, mute discourages spontaneous discussion.”

Then there are basic meeting best practices: “What is the goal? Do you have an agenda? What materials do you send? All these things are so poorly done,” Argenti laments. “I had a meeting on the phone recently, and they knew I would be traveling. They then sent me something to read while I was driving. That’s just bad planning”

Nick Morgan, the author of Power Cues, suggests planning virtual meetings in 10-minute segments because of evidence of shrinking attention spans. He also says that facilitators should pause regularly for group input.

Also, know who to invite and who not to. “Being a participant in an unnecessary meeting is not productive and it might not even be active, but it looks good on a time sheet,” Bellmar points out .”People continue to get ‘real work’ done while passively attending a meeting and think they are effectively performing their tasks.”

Argenti agrees. “It’s just like cc’ing people on email,” he says. “The facilitator needs to think hard about who needs to be there.”

As for remote meeting participants, Paul Argenti recommends using a headset as opposed to a cell or even office phone on speaker. “If the phone is further away, and the computer is closer, it’s easier to focus on the latter,” he says.

He’s also a proponent of reminding people you’re there. “Twenty to 25 minutes into a meeting, ask a question or make a comment to remind people you’re part of the discussion.

Nick Morgan also points out the importance of getting emotion across, something that’s more difficult to do on the phone since we lack visual cues. So be deliberate about your words: “Say, ‘I’m excited about this next bit of news, because it means that…” Or ‘Jim, I’m really surprised to hear that third quarter’s numbers aren’t improving. Surprised and worried, actually. How are you feeling about them?’

“You’ve got to put back in what the phone lines are removing.” Even if you’re at the beach.

Help Employees Think on Their Feet

When employees don’t have enough information about projects or goals, the fog of indecision can settle in – people make the wrong decisions, or no decisions at all. In the corporate landscape, many employees aren’t given enough business context to be able to spot or distinguish threats and opportunities. They’re unable or unwilling to make critical decisions without being told what to do. That inability to act decisively can be crippling. Sometimes staffers fail to make informed decisions in the moment because they haven’t been given the training or the autonomy to do so. Employees too often decide that, because they can’t see clearly on all sides, they can’t move – even if the spot upon which they’re standing is the worst place to be.

At the company I co-founded, where several members of our leadership team have special ops and intelligence backgrounds, we’ve adopted a military phrase to describe the behavior we want to see from employees when it comes to decision-making: “Get off the X.” In the military, this roughly equates to “stop being a target and become an agent.” In our business context, we use it to describe making critical decisions the moment innovative action is needed, without waiting for a supervisor to sign off. To sustain a decision-making culture and avoid tunnel vision, employees need autonomy, training, awareness, responsibility, trust, and agility. In our company, an enterprise security provider, this is how we ensure our employees avoid the fog of decision-making so they can get off the X and move the whole business forward:

Encourage teams to work outside their own silos. One way to burn off the fog around decision-making is to nurture cross-functional capabilities. In doing so, employees are able to view challenges from multiple vantages, rather than solely through the lens of individual domains. People are less likely to be paralyzed by the unknown. We push our team members to broaden their areas of expertise so they can adopt different perspectives when problem-solving. For instance, an employee in data loss prevention might attack her own system to find any weak spots. So rather than trying to find solutions once a breach or loss arises (i.e., reacting defensively), she goes on the offensive to circumvent a problem altogether.

Commit to the outcome, not the course. A predetermined course can’t anticipate all risks. We need employees who can make decisions based on imperfect, but optimized, situational awareness, and who can then pivot when those factors change. We saw this recently when an employee implemented data classification and identity access management programs for a client. In doing so, he noted a host of defections because the security policies didn’t adequately account for the specific activities and needs of the affected business units. As a result, he had to slightly shift his focus to help the client align its security policies with the business context.

Reward teams and individuals for “Getting off the X.” At our company, we link performance ratings and training opportunities to excellence in client delivery. We also use incentives to promote quick thinking and flexibility. To recognize team efforts, we not only provide traditional financial awards, we also memorialize strategic contributions at a corporate level in our “all-hands” meetings. And to emphasize the message that there is no place at a start-up for passive employees, we also give out a quarterly “Get off the X” award to individuals. One winner was a mid-level analyst whose main responsibilities were technical, but who proactively supported a corporate development initiative. Everyone is focused on spotting and celebrating decisive action. We get nominees for the award from all over the company. Our employees know that empowerment comes with the responsibility to not only identify challenges, but to respond to them.

Of course, there are limits to this practice of acting quickly, without supervisor approval – it must focus on areas where employees have sufficient training to know what to do. But inaction is rarely the right choice in high-stakes moments. Because the hazard zones for businesses, particularly emerging ones, are ever-changing, it’s crucial to equip employees to be more agile and inventive. To grow a successful company, make sure your employees know how to get off the X when it counts.

Managing Your Emotions After Maternity Leave

When you’re a new mother, it feels like everyone wants a piece of you — literally, figuratively, and emotionally. Add physiological changes, a lack of sleep, and hormonal fluctuations into that mix and it’s easy to understand why returning to work after maternity leave can be one of the most fraught, challenging, and stressful times in a woman’s life. A woman may want to lean in, but her sense of equilibrium might be so off kilter that she’s not sure which direction she’s leaning in, or whether she’s leaning at all — or just trying to find her footing on what she’s no longer sure is a level playing field.

After Lisa, a senior member of a consulting firm, returned to work, she had to face both her own cocktail of powerful emotions and complex organizational politics. While most women don’t face every situation she experienced, many do confront at least a few of them. And Lisa’s reaction — ultimately, to say nothing — is all too common.

She had been the “golden child” at her organization, working in close proximity with her boss on several key initiatives. Preparing for her maternity leave, her boss had arranged for a new employee, technically Lisa’s peer, to temporarily handle her work. However, Lisa returned to find that the new staff member had completely taken over the department and ingratiated herself with their boss. She acted like Lisa’s superior instead of her peer. Lisa watched in anger as she methodically encroached on others’ jobs in the organization, took undeserved credit for others’ work, and systematically expanded her responsibilities and power base.

At the same time, a male coworker, even though he was her junior, hazed Lisa for a year, continually teasing her about all the work done he’d on her behalf, and asking questions about her work commitment.

Normally unflappable in the face of such behavior, she now found herself doubting her own reactions. She began to wonder if she was being oversensitive due to her own feelings of being beleaguered on all sides, tired all the time, and feeling like a failure compared to her pre-baby, well-rested self. Though filled with anger, she did not confront either her rival or her gadfly, or discuss the situation with her boss—and when a competitive offer from another company arose, she seized it and left. It was a decision she ultimately came to regret: her boss was blindsided and shocked at her departure, and several months after Lisa left her position, her nemesis was fired.

In my work as an executive coach, I have found that successful women often keep their struggles private in difficult re-entry situations. This may be because they don’t want others to view them as weak; because they don’t feel like they have a confidant they can trust (their mother-friends may judge them, while other colleagues may take advantage of them); or it may simply be that they don’t want to open a Pandora’s Box of emotional pain by talking about it. The result is often self-doubt and compartmentalizing—one woman told me that she cried for months on the way to and from work, then stoically focused during the work day. In a short-term crisis, compartmentalizing can be fine, perhaps even healthy. But motherhood is neither short-term, nor a crisis, so we need some more effective approaches:

Be well informed about typical post-partum emotions so you don’t feel that your reactions are abnormal or that there is something defective or inadequate about you. Try to be open to your feelings and to experience their full range, which will make you less likely to fixate on any given issue or challenge, such as a workplace rival.

Figure out what you want independent of what is happening at any given moment in your workplace. If you make the decision to work full-time, it should be because that’s what you’ve decided to do, not because you feel you need to compete with a particular peer for your boss’s favor or for key assignments or responsibilities. Similarly, if you decide to leave that job (or the workforce) it should be because that’s what you want long-term, not because your current situation feels untenable.

Get the support and kindness you need, whether that be from a few trusted friends, internal or external advocates or mentors, or a counselor. In particular, women who have already been through it will be glad to share their stories, lessons learned, and to dispense advice based on their own experiences. Many women are surprised by the support and validation they get when they signal openness to it. Also, try your best to not isolate yourself from friends and others who care about you and your wellbeing. Your time with them, no matter how limited, can be healthy and restorative.

Find even small ways to build your executive stamina through fitness, meditation, nutrition, hydration, and getting as much sleep and sunlight as you can. Take breaks when possible at home and at work to restore your energy and recharge your batteries. This may mean hiring a sitter just so you can go upstairs and take a nap; that’s OK. It may mean requesting more of your partner, family, or community; that’s also OK.

Prepare in advance for difficult conversations, whether with your boss or with a workplace rival. Maintain your composure and professionalism, and plan to use positive, solution-seeking language that doesn’t imply criticism or appear accusatory. That’s a best practice almost all of the time, but it is even more important if you’re in a workplace where colleagues are using your leave as an excuse to undermine you; losing your cool will only give them more ammunition.

Regaining your energy through these healthy methods will mean you will have less need to draw upon stress as its own energy source. While stress can be an energizing motivator in the short term, the long-term effects are dangerous. Don’t try to sprint the marathon. But also don’t worry or beat yourself up too much if you do lose your balance from time to time. Every new mother does, whether or not she is trying to balance family and career goals. I realize it’s easier said than done, but if it feels like no one in the world is cutting you any slack, at least try to cut yourself some slack.

4 Ways to Fix the Q&A Session

As a professional public speaker on innovation, I’ve often wondered why people seem so attached to the idea of ending keynotes with a Q&A session. Most Q&A sessions are mediocre experiences at best: an instantly forgettable interlude before the coffee break. The very format, I’d argue, is a dysfunctional relic of the past, unthinkingly added to agendas everywhere, and I believe we need to rethink it.

To be clear, it’s not that the intention of having a Q&A session is bad. For better or worse, most conferences leave the audience in “listening mode” most of the time, so it can make perfect sense to give the participants a voice and allow for some unscripted interaction with the speakers. But in reality, nine times out of ten, the Q&A sessions end up being the weakest part of the event.

There are many reasons for this, including the fact that not all speakers are good at handling questions, but the fundamental issue comes down to two things: audience inactivity and the quality of the incoming questions. In my experience, about a third of the people who grab the microphone will ask interesting questions. Another third will either ramble or pose a narrow question that is really only relevant to the person asking it. And the final third don’t have a question — they just want to say something, which can be fine, only the Q&A format somehow makes that awkward. Meanwhile, 95 percent of the audience is still stuck in passive listening mode.

Some solutions to the Q&A dysfunction already exist. Some hire a professional moderator or use software tools to crowdsource the questions. Others experiment with radically new ways to run events, such as the unconference movement. However, those solutions are often expensive or time-consuming to deploy, making them infeasible for many types of events. Here are four techniques that I’ve used with great results, and that can be deployed without any kind of preparation:

Do an inverse Q&A. An inverse Q&A is when I (the speaker) pose a question to the audience, asking them to discuss it with the person sitting next to them. A good question is, “For you, what was a key take-away from this session? What might you do differently going forward?” People love the opportunity to voice their thoughts to someone and unlike the traditional Q&A, this approach allows everybody to have their say. It also helps them network with each other in a natural manner, which is something many conferences don’t really cater to.

Ask for reactions, not just questions. When you debrief on the small-group discussion, insisting on the question format makes it awkward for the people who just want to share something. As you open the floor, specifically say “What are your reactions to all this? Questions are great, but you are also welcome to just share an observation, it doesn’t have to be in the form of a question.”

Have people vet the questions in groups. An alternative to the inverse Q&A is to ask people to find good questions in groups. Simply say, “Please spend a minute or two in small groups, and try to find a good question or a reflection you think is relevant for everybody.” Then walk around the room and listen as people talk. If you hear an interesting reflection, ask them to bring it up during the joint discussion, or bring it up yourself.

Share a final story after the Q&A. Given that even the best-run Q&A session is unpredictable, it is best to have the Q&A as the second-to-last element. I always stop the Q&A part a few minutes before the end, so I have time to share one final example before getting off the stage. That way, even if the Q&A part falls flat, you can still end your session with a bang instead of a fizzle.

The above methods can help you turn any keynote into a better experience. What other techniques — ideally simple ones — have you seen or used?

Pity the Poor Local Government Worker

35% of insect-related injuries to U.S. workers affect state and local government employees, even though those workers constitute just 14% of the nation’s workforce, according to a Labor Department tally reported in the Wall Street Journal. New Mexico leads the nation in insect injuries of workers, with 8.3 per 100,000 people living in the state in 2010, well ahead of No. 2 Georgia, which has 6.3. The state of Texas leads in insect deaths, with bees the main culprits.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers