Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1380

August 18, 2014

Age and Gender Matter in Viral Marketing

Nearly every digital marketer has a goal of creating a viral campaign. Getting mass exposure for high-quality content provides huge value to clients, but it’s not always easy to pull off; it takes an understanding of the complexity of human emotion and how it plays into consuming and sharing content online.

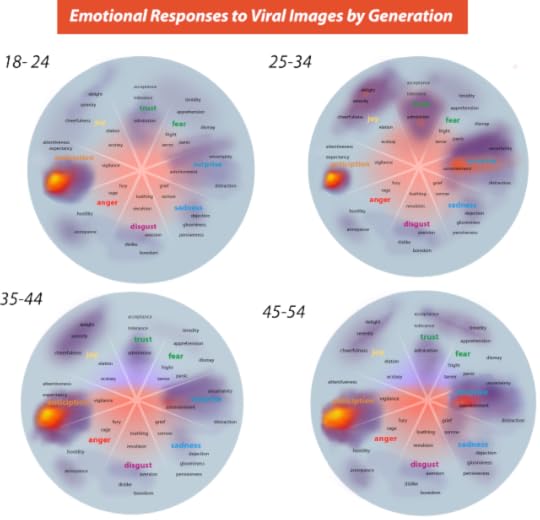

To gain better insight into what makes people share content online, Fractl studied the emotions associated with viral marketing campaigns, plotting the ones that are most commonly associated with viral content on Robert Plutchik’s comprehensive Wheel of Emotions:

Curiosity

Amazement

Interest

Astonishment

Uncertainty

Then, we looked more closely to see how certain demographics respond to different types of content.

To get a better understanding of how people of different genders and ages react to content, we surveyed 485 people online and asked them to indicate which emotions they felt when viewing 23 viral Imgur images we chose from over a three-month period. They could select feelings related to joy, sadness, fear, disgust, or surprise by choosing an adjective related to that emotion. We also conducted a similar survey featuring non-viral images instead of viral ones for comparison purposes. The subtle differences we discovered could have big implications regarding the nature of virality and content marketing.

One of the more interesting insights in our study comes from the 18-24 age group. This age range reported feeling fewer positive emotions while looking at the overall group of images compared to the participants in the other age groups. Specifically, they reported fewer emotions related to joy, trust, or surprise (the latter we considered to be an “other” emotion, as it can be both negative and positive). This lack of positive response can mean that this age group is more difficult to target.

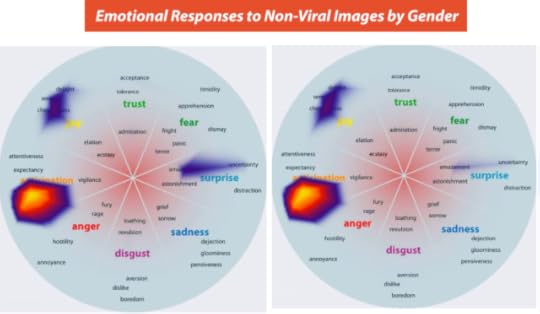

This group’s reports of surprise are noteworthy, as well, because this emotion has an important role in the probability of going viral. When we compared reactions to viral and nonviral images, we found that viral images were more likely to trigger reactions of surprise than non-viral images were, while there was no significant difference among the other emotional groups. This indicates that surprise may be a central component to what makes an image go viral.

Given that the 18-24 age group had fewer reported positive and surprise-based reactions to images, this demographic may be more difficult to engage with and could require additional targeting. It’s possible that this age group is simply inundated with images online (like the 11% of those aged 18-29 who use Reddit.com) and thus they are more discerning and harder to emotionally activate. Since their threshold is higher, you’re more likely to engage them with particularly new and highly intriguing content.

The 25-34 demographic has something in common with the 18-24 set, which is that both groups reported feeling fewer interest/anticipation emotions compared to the older two age groups. It’s possible that this is because younger online users are more captivated by dynamic forms of media rather than the common static images that were used in our study. However, this group also reported more emotional complexity than any other age group, making them the most likely to share content that incorporates a range of emotions — once their initial views are earned.

In contrast, Gen X and Baby Boomers reported more positive and interest/anticipation emotions when viewing static images. Therefore, when creating campaigns targeted at these two age groups, you’ll want to focus on those that incorporate emotions such as joy, trust, interest, and anticipation. This is a key insight for marketers planning campaigns on LinkedIn, which is the social network home of the largest percentage of older audiences.

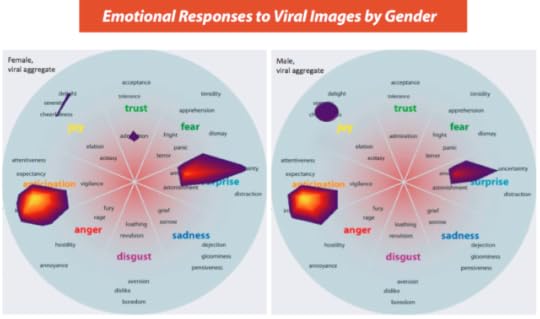

The differences in gender are less dramatic than the differences in age groups. Men and women generally reported the same number of instances of feeling each emotion when viewing the viral images overall. There was one emotion type that approached a statistically significant difference, though: joyful emotions. Men reported feeling more joyful emotions than women did, which could mean that women might be slightly less likely to respond with positive emotions, possibly becoming a factor in whether or not they’ll view content. However, women did feel one positive emotion — trust — statistically more than men, which may be key for earning their initial views.

When we compared the responses to viral and non-viral images, we found that women experienced a greater variety of emotions. While both men and women reported more fear, surprise, sadness, and anger emotions when viewing viral images compared to non-viral images, only women statistically experienced more emotions related to trust, in addition to more negative emotions and total emotions overall.

If you’re trying to target women, it might be worth aiming to generate trust in order to promote sharability.

The fact that women experienced a greater variety of emotions is also significant, because we found that viral images activated more emotions overall than non-viral images did. In a nutshell, if an image evokes complex emotions, it has a greater chance of getting shared. The female propensity toward experiencing a range of emotions may make women more likely to share, but their fewer positive feelings may pose a challenge in garnering crucial initial views.

Conversely, men may be more likely to view content, based on their reports of greater positive emotions, but less likely to share due to less emotionally complex responses. Marketers may want to target emotions in men that can help increase the variety of emotions they feel; for example, since we previously mentioned men reporting more joy-based reactions to viral content, contrasting emotions such as sadness or fear could be prioritized to create a more complex emotional field and balance out the potential for joy.

As you create content, keep this in mind: Consideration of positive feelings and emotional complexity, and the challenges of achieving each with various demographics, will give your content an edge in its chances of going viral.

How to Finance the Scale-Up of Your Company

Tom Szaky knows well the meaning of the saying “Beware your dreams, for they may come true.” With the 2004 Christmas retail season rapidly approaching, he was trying everything he could to scale up TerraCycle, a two year old venture selling liquid worm poop as fertilizer in used PET bottles. So far, he had been successful distributing through lots of smaller retailers, but had encountered a flood of rejections from the big box stores. Undaunted, Szaky finally landed a 15 minute meeting with Walmart Canada’s buyer. Instead of telling Szaky to “drop off the face of the earth” (he had been warned this was likely) Walmart Canada placed a huge order — for every one of its stores. But as he recounts in his engaging book, achieving his dream quickly turned into a nightmare when he was confronted with a stark reality: they had sold to Walmart without having the necessary infrastructure in place to handle the huge volume increase. Fortunately for Szaky, he had already laid the groundwork of financing from suppliers, equity investors and others to allow them to double sales in two months.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the most dangerous period for entrepreneurs is not when they start up from scratch but when they scale up for growth. When you are a startup, there is relatively little to lose, mistakes are fixable, and a small amount of cash and a cohort of committed colleagues can go a long way. But when you suddenly accelerate and grow, whatever your company’s age, things get really hot really fast, largely because your need for cash explodes overnight. Most entrepreneurial ventures, whether they are startups, spinoffs, or smaller companies which have been around for awhile, haven’t given enough thought or planning to financing for rapid scale-up. Here are some ways to keep the heat of new growth from melting you down.

Use multiple sources of finance. Many entrepreneurs who are propelled into a sudden growth trajectory think mostly about raising risk-sharing equity investment from venture capitals or private “angels.” But when you scale up, it is faster, more feasible and less dilutive to cobble together your financing from a combination of equity investors, banks, public funds, suppliers, credit cards, customers, and even employees who will take stock options in lieu of some cash. One retailer I know discovered that the $100 or so penalty to defer California sales tax by a month was actually a cheap source of financing. It doesn’t make as glamorous a story as “raising $5 million from top-tier Valley VCs,” but this is how growth financing typically works in reality.

Cross-leverage money from one source into cash from others. It may seem counterintuitive, but owing money to banks often makes you more attractive to equity investors, not less. To the risk investors, bank debt means that very conservative and experienced eyes will be watching your performance so that you make every payment on time. The risk-friendly equity investor also sees the debt as a cheap way to leverage their returns. So when you get some equity investment, rather than looking for more of the same, immediately talk to the bankers, the state funding agencies and other more conservative lending institutions. Particularly with investors and lenders whose interest is in securing the viability of your growing enterprise, it’s to your advantage to ask before you secure other sources of financing. This kind of cross-leverage strategy diminishes the inevitable “free rider problem” (i.e., we’d love to see you succeed but we’re happy to cheer you on from the sidelines).

Speak different dialects with different capital providers. When you do cross over to talk to the bankers or other financers, learn how to speak their language. Entrepreneurs often get caught up in the heat of the moment: “My venture is scaling up so fast, what an opportunity!” Banks don’t care about opportunities in the abstract — they care about opportunities that repay their principal plus interest, on time, or else securing the debt with other assets they can seize. Public funders — the various state economic development agencies — don’t care about opportunities in the abstract, either, but about opportunities that create jobs, particularly where unemployment is raging. Research institutes, for example, care about seeing their IP solve important problems so they can get more funding themselves. Philanthropies and advocacy groups with funds to disburse care about progress in their area of focus. You get the point. In dealing with diverse potential funding sources throughout your enterprise’s growth, you always need to keep top-of-mind the question “What’s in it for them?”

Be opportunistic about raising money. Of course, both business school and real life experience teach us that it helps to plan out your moves in advance — and it does. But scaling up rapidly is more like piloting a sailboat in open waters than running a train along fixed tracks: chart your course, but take advantage of the waves, currents and weather, and nimbly avoid storms when they approach. Vaunted valley VC, Eugene Kleiner said it well: “The time to eat the hors d’oeuvres is when they’re being passed round.” Many an entrepreneur has passed on the hors d’oeuvres, only to regret it later. As an investor, I have seen quite a few ventures fail from running out of cash. I have yet to see a venture fail from too much dilution.

Manage accounts receivable like a hawk, but pay on time. In my company (Isenberg) we developed a 90-day rolling prediction of our daily account balances that, over the years, became increasingly precise. This saved us hundreds of thousands of dollars in financing. Managing payables is just the flip side of the receivables coin. Pay on time. I know this sounds counterintuitive. Like most firms, my company weathered numerous market ups and downs. Because we meticulously paid suppliers on time when we were cash-rich, we could go back to them for additional time to pay when times were tight. Supplier financing is a powerful, hidden source of cash that works best when times are bad, and is much harder to secure when times are good.

Cultivate customer financing. The flip side of supplier financing is to ask your customers for financing. This can take different forms, including up-front payments, down payments, or covering some of your development expenses, usually of course for a discount on their purchases from you in the future. To secure financing from customers is not necessarily easy: to get it, you will need to understand deeply what their needs are (present or future) and present a compelling pitch for how you can address those needs better than anyone else. In contrast to supplier financing, customer financing is usually more feasible when times are good and customers have cash on hand. But remember, both customer and supplier financing will require you to be skillful in showing how you compellingly address their unmet needs: for example, suppliers want to have a reliable, long term customer who pays predictably; customers want to have the most advanced technology that will give them a competitive edge.

All successfully growing entrepreneurs keep their eye on cash flow and they do it best by having a broad range of capital sources — and cash substitutes — to draw on. Remember, whether you are a later stage startup or a second generation family venture, a thoughtful and flexible financial plan focused on scale-up will allow you to grow fast, be responsive, and thrive.

Should You Put World of Warcraft on Your Resume?

Warren Buffett and Bill Gates are famous for their love of and prowess in bridge. Harvard has used high-stakes poker as a real-world game theory laboratory for strategic thinking. For sheer bonhomie and bonding, golf remains a global opportunity for American, Asian, and European executives to mix business with pleasure. Depending on the industry, a sharp MBA who’s a scratch golfer may well have a leg up in a job interview or sales meeting.

Demonstrable talent and success at games that mix competitive fire with social skills make a desirable human capital combination. There’s a perceived correlation between real competence in serious games and business effectiveness.

But do massively multiplayer online role-playing games like World of Warcraft or Grand Theft Auto Online enjoy comparable corporate cachet as golf, poker or bridge? An amusing Wall Street Journal story strongly suggests not. A top IT executive recruiter, for example, noted that “his clients haven’t sought hires with game experience.” The ambivalence around virtual gaming is practically—if not ironically—palpable. MMPORGs and their networked ilk are regarded more as adolescent indulgence than an admirable recreation.

That reflects a snobbish and elitist generational anachronism. The cognitive and social skills demanded in complex multiplayer games can be every bit as subtle, sophisticated and challenging as stud poker or bridge. Indeed, I know Silicon Valley and (admittedly younger) hedge fund quant teams who bond and boost morale through their Minecraft bouts. I may not fully understand the details of what they’re doing but there’s no doubt that these interactions are building relationships as well as protective structures. These teams —and the organizations that employ them—would likely welcome colleagues and candidates with authentic video-game passion and talent. Trust me, these folks will not be golfing at Torrey Pines. (They do, however, play poker—both online and around a table. The pots impress.)

Might a 38-year-old project manager face mockery listing her high-performance Halo scores on her LinkedIn profile? Possibly. But there’s something to be said for people who can succeed in intensely competitive environments and clearly know how to navigate in hostile virtual worlds. The simple and undeniable truth is that more and more knowledge work and professional collaboration takes place in digitized environments. Does competitive competency in Minecraft or World of Warcraft make someone a better manager or motivator? No more so than playing bridge well or playing golf at a 5 handicap. But the need for social sensitivity and learning fast is there. The demand for a certain level of self-discipline and adaptability is there.

Just as the Moneyball sensibility transformed professional sports worldwide, the ability to perform well in fantasy sports leagues signals that somebody has a decent grasp of probabilities, risks, and opportunities in a competitively transparent and transparently competitive environment. That’s a capability that deserves discussion even if it’s not directly on enterprise point.

My view of the current reluctance of recruiters and HR department to give MMPORGs and their digital counterparts their human capital due is the inertia of ignorance and elitism. Golf, yes; Minecraft, no. Poker, maybe; World of Warcraft, you’ve got to be kidding, right? But as companies catch up and realize that a new generation of video games makes their players smarter, more alert, and more socially effective as teams, watch those LinkedIn profiles change.

Incompetent Managers Don’t Want to Hear Your Ideas

In an experimental role-playing scenario, “managers” who were primed to feel incompetent were more likely to denigrate the competence of an “employee” who spoke up and proposed a new operational plan, according to a team led by Nathanael J. Fast of the University of Southern California. The managers who felt unable to fulfill their job expectations rated the employee more negatively than did those who were primed to feel competent. Incompetent managers who are personally threatened by employee suggestions send signals that they are unreceptive, shutting off avenues of new ideas, the researchers say.

When a Spinoff Makes Strategic Sense

Gannett Corporation, like Time Warner and News Corp, has recently announced that it will split its print news businesses (USA Today and 80 other newspapers) from its media businesses (TV channels, Cars.com, and other internet businesses).

A split-up like this is hardly news. Companies have been splitting off and de-merging businesses for more than twenty years, and the logic is usually pretty obvious to the lay observer. Spinoffs and splits can be justified by financial modeling around the relative profitability and growth prospects of the units involved, by giving a company greater focus or by allowing it to unload units that have been a drag on growth.

Yet although the lay observer can understand the reasons for these corporate break-ups, the frameworks and ideas that underpin strategy theory are actually pretty unhelpful when considering whether or not to initiate a break-up.

Let’s look at our current dominant strategy theory: the Resource-Based View or RBV, closely associated with Jay Barney. According to this theory, the “resources” that a firm possesses determine whether it succeeds or fails. Strategic decision-making, therefore, is about building or exploiting “resources.”

What exactly is a “resource”? The theory defines it as an asset that enables the firm to earn a “rent” or in layman’s terms a good profit. In order for this to happen, a “resource” must have three features. It must be:

Valuable to customers or enable the creation of something that is valuable to them;

Rare, meaning that it is not possessed by most competitors; and

Hard to copy or substitute, so that competitors cannot easily build or match the same resource.

Typically, resources that satisfy these conditions are capabilities or know-how that have been developed over time and are hard to transfer or document. But they can also include property or patents or brands or contracts.

Gannett clearly has resources in both its original newspaper businesses and in its more recent media businesses. We know this because both businesses earn returns that are reasonable for their industries. This would not be possible unless these businesses had some resources that met the definition above.

So how does RBV explain the decision to split the company into two? To understand it, we would have to believe that splitting print from media either creates a new resource or makes it easier for the company to exploit an existing resource. It seems evident that the split does not create a new resource, and it is not obvious why splitting would enable the management team to exploit existing resources better. So it is hard to explain this decision using the RBV.

You may also have noted that the RBV contains no concept of focus. Indeed, if you have multiple resources, the RBV implies that you should develop a strategy to build and exploit all these resources. It does not explain why you might be wise to focus on some resources and spin off other resources.

So maybe there is a better theory of strategy? The main alternative is the Positioning School, whose ideas were most clearly expounded by Michael Porter. This theory states that success is dependent on positioning your business in a profitable market, where it will have or can gain a competitive advantage.

Unfortunately this theory also fails to explain the decision to split. Splitting the business does not change the position of either half. The print business remains in an unattractive market, and the media business remains in an attractive market. Moreover, the split does not change the competitive advantages either.

To explain decisions like Gannett’s split, therefore, we need some adjustment to our theories of strategy. My own solution is to add a concept to the RBV.

Currently, the RBV is built entirely around assets. There are no liabilities other than the absence of resources. So strategists are encouraged to focus on the resources that they have and those possessed by their competitors, and to develop a path forward that builds and exploits their resources while avoiding or undermining the resources possessed by competitors.

The RBV would be a stronger theory if it contained concepts for both resources and liabilities. A “liability” could be defined as a feature of the firm that is:

Detracting value from customers or makes it harder for the firm to create value for them;

Rare, not possessed by most competitors; and

Hard to eliminate, not easily eradicated, traded or jettisoned.

Examples of liabilities might include the British newspaper News of the World’s reputation for illegal telephone tapping (which caused News Corp to close the paper); legacy IT systems in retail banks (which causes them to be slow to react to market changes); a low-cost, highly efficient operating process in a volatile or fragmenting market (think of IBM’s mainframe business in the face of mini computers and desk tops); having highly skilled and highly paid employees in a commodity market; a belief that investments in technology will solve most problems, in a market where the technology is already surpassing the customer’s needs (think of Christensen’s disruptive innovation theory).

So how would the addition of a concept of liabilities to the RBV help us explain Gannett’s decision? According to the CEO of Gannett, Gracia Martore, one reason for the split is that the combined businesses had a liability: anti-trust restrictions.

Because the company owned a range of media businesses, both units were finding it difficult to make some acquisitions. “It has been difficult for us to look at certain acquisition opportunities,” she said. “We now have two companies that are unfettered.” For example, in print, “We can now do smart, accretive acquisitions of community newspapers in an unlevered company where they can create tremendous synergies.” So Gracia Martore is suggesting that the spin off was about removing a liability — anti-trust restrictions — that was subtracting value.

Other liabilities might also lie behind this decision. Maybe it is difficult to manage a growing business alongside a declining business. Private equity firms have shown that it is often better to separate out cash generative businesses; so that managers can focus on this task without looking jealously over their shoulders at their more favoured colleagues in growing sister divisions. One can imagine, for example, that pay discussions for journalists would be a difficult management challenge when both businesses are together. The media businesses may want to increase pay to attract more talent, while the print businesses may want to reduce pay to keep down costs. Hence, having the growing and declining businesses together could be a liability for both businesses with regard to managing its most critical resource — journalists.

With this additional concept of liabilities, the RBV would be able to explain the decision to spin off. It might need to be rebranded the Resources and Liabilities View, which would bring it closer to its origins in “strengths and weaknesses” analysis. The RBV has helped us understand what a “strength” is. But in the process caused us to lose sight of “weaknesses” as an equally important concept. With this additional concept RBV can provide the strategy field with a firmer academic base than it currently has for guiding managers and for explaining the full range of successes and failures.

August 15, 2014

Sales Still Matters More than Social Media

It’s become commonplace for observers to tout the transformative potential of digital technologies and bemoan the allegedly slow pace at which companies support these initiatives. Two recent blogs published by HBR.org are representative and, I believe, wrong.

Walter Frick, an HBR editor, contrasts the enthusiasm of executives for spending money on digital initiatives versus their relatively unsupportive boards. “Digital growth is appropriately a priority for a diverse swath of organizations, and boards need to get with the program,” he writes. Didier Bonnet of Capgemini agrees, and is refreshingly direct in suggesting the cause: the average age of independent directors in S&P 500 companies is almost 63, they did not grow up with online technology, and many should be replaced for their lack of “digital awareness.”

Both cite a McKinsey survey which, ironically, found that “Organizations’ efforts to go digital . . . are picking up steam.” But look at what that survey also found: “Less than 40% of executives say their companies have accountability measures in place, either through targets, incentives, or ‘owners’ of digital programs, while only 7% say their organizations understand the exact value at stake from digital.” In other words, the current de facto digital business case in most companies goes something like this: “We’re not sure what the objectives are or how to calculate the ROI or who has responsibility here for clarifying those things and driving accountable execution. But invest in this digital project and ignore the opportunity costs—i.e., what else we could be doing with that money, time and people to drive customer acquisition and profitable growth.”

This is a caricature, but not by much. If you read the business press, you could easily assume that proficiency in social media or online data analytics now determine business success. But consider:

According to a Gallup survey, about 62% of U.S. adults who do use social media say these sites have absolutely no influence on their purchasing decisions; 30% say the sites have “some” influence, and only 5% say they have a great deal of influence. Is it any wonder that it’s tough to calculate the ROI? And is the key to success here the technology, or fundamental segmentation and buying-process criteria?

Even within the active-user segments, there is evidence that comprehension and retention decline significantly when information comes online. (See, for example, “Is Google Making Us Stupid? The Impact of the Internet on Reading Behaviour,” a paper reporting the results of research at the 27th Bled e-Conference). There is other evidence that the reported clicks and other alleged user-data on many social media sites are simply unreliable. Wouldn’t you want to know more about this before approving your firm’s investments?

Another McKinsey survey, conducted in 2011, found then that the average company with more than 1,000 employees already had more data in its CRM system than in the entire Library of Congress. Those firms undoubtedly have even bigger data now. But is that how growth occurs or, in the absence of measures and objectives, how yet another garbage-in-garbage-out cycle gets going in many firms?

If you peek behind the server farms of online firms themselves, you will find face-to-face and inside sales groups as the engine of profitable growth, and you might be surprised to know the bigger percentage of total employees at firms like Facebook, Google, and Groupon that work in sales, not technology or data mining.

Good boards ask these questions before getting with the program and, as always, bad boards follow fads. Good boards also pay attention to where and how money is spent and resources allocated.

The amount spent, annually, by U.S. companies on field sales efforts is 3X their spending on all consumer advertising, more than 20X the spend on all online media, and more than 100X what they currently spend on social media. Selling is, by far, the most expensive part of strategy implementation for most firms. Sales forces have NOT been replaced by social media or other internet tools. According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of people in sales occupations in 2012 was virtually the same as in 1992—before the rise of the internet. And this almost certainly understates the real numbers because, in an increasingly service economy, business developers in many firms are called Associates or Vice Presidents or Managing Directors, not placed in a “Sales” category for reporting purposes.

When I cite these numbers, many business people and most twenty-something MBA students are surprised. That’s understandable because, in comparison to the hype about digital initiatives, you hear very little about sales in the contemporary business media.

Why? One reason may be that journalists have seen their industry rapidly transformed by digital technology. The peak year for newspaper profitability in the U.S. was as recently as the turn of this century. As the old saying goes, “When my neighbor is out of work, it’s a recession; but when I’m out of work, it’s a depression.” That’s also understandable, but it’s still a cognitive bias. Another reason is perhaps the natural interest that technology vendors and consultants have in promoting the next big thing, especially as hardware and software products become commoditized. That, too, is understandable, but caveat emptor.

The big story is that the internet is realigning, not eliminating, sales tasks, and that deserves more attention in business media.

My point here is certainly not to defend boards. I’ve sat there, and I agree there is lots of room for improvement. But focusing on digital initiatives may be perfectly backwards when it comes to improving governance. When boards ask relevant questions about digital investments and focus attention on the much bigger chunk spent on still-crucial sales resources, they are not being reactionary or senile. They may be following Mark Twain’s sage advice: “If you put a lot of eggs in one basket, then keep your eye on that basket!”

Just Take a Vacation Already

I like FullContact's approach to getting employees to take vacation: The Denver-based contact-management company offers workers $7,500 a year to help finance their vacations. The incentive seems to be working, because employees are now using a lot more of their accrued time off, the Wall Street Journal reports.

A depressing number of people don't take the vacation time they've earned, for reasons ranging from not being able to figure out what they'd do on vacation to wanting to appear gung-ho to their bosses. Something like 15% of American workers who are entitled to paid vacations (and many aren't, which makes the U.S. an anomaly among wealthy nations) haven't used any of it in the past year. Equally depressing is that in certain cases, employees are right to worry about the consequences of disappearing for weeks at a time. One study showed that 13% of managers are less likely to promote workers who take all of their vacation days; another revealed that employees who take less than their full vacations earn 2.8% more in the subsequent year than their peers who took the full measure of their allotted time. All of this despite the fact that we know it's important to take a break — and that we have the tools to make it painless (nay, enjoyable!) for all involved. —Andy O'Connell

Substance Over Style In Search of StarterESPN

I'm a sucker for "the rise and fall of" narratives, especially when they're about beloved childhood memories. So thanks, Mina Kimes, for this chronicle of Starter, the puffy, sports-logo-emblazoned jacket that dominated my youth. Catching up with Starter's founder, 71-year-old semi-retired real estate investor David Beckerman, Kimes reveals a story not so much about a brilliant business strategy but about pure luck. For example, Beckerman once gave an employee a donation for his church; turns out the employee knew MLB manager Joe Torre, who was so taken with Beckerman's generosity that he often wore Starter.

A similarly strange coincidence resulted in famed running back Emmitt Smith wearing the brand. And while the company eventually went under after years of healthy revenue, nostalgia for the jackets hasn’t waned. "Sports today are marketed with such self-seriousness — athletes are warriors, games are battles, T-shirts are armor," Kimes writes after watching an absurd old Starter ad featuring Rodney Dangerfield and DJ Jazzy Jeff. "By contrast, Starter's goofy irreverence delights."

Great Awakenings Unequal Pay for Women: 'I Was Told Men Should Make More'The Guardian

We all know the research: Women are persistently paid less than men. But it's also important to remember what that actually looks like day-to-day — and what happens when women stand up for themselves. So The Guardian and ProPublica asked women readers to recount moments when they found out they were being paid less than male counterparts for the exact same job, so-called "equal pay awakenings." The comments are replete with tales of deliberate discrimination: One company offered family medical insurance to men but not to women with children, and another hired a man for $3,000 more per year than his wife was offered for the same job in a different company so that he would be making more than she was. Then there are the female painters who were told they had to "prove we deserved to be paid the same as men" by painting "an entire house without the assistance of any males."

School Days Simplifying the Bull: How Picasso Helps to Teach Apple's StyleThe New York Times

Oh, the mysterious inner workings of Apple. Perhaps one of the most hidden aspects of the company is its internal training program, which Steve Jobs introduced "as a way to inculcate employees into Apple's business culture and educate them about its history, particularly as the company grew and the tech business changed," writes the Times's Brian X. Chen. No photos of the classes exist, and Apple refused to make instructors available for Chen to interview. Nonetheless, he was able to stitch together an understanding of the program through interviews with three anonymous employees. Here's what he learned:

Classes are taught by full-time faculty from Yale, Harvard, Berkeley, and other schools. They're tailored to different departments and job titles; for example, "one class taught founders of recently acquired companies how to smoothly blend resources and talents into Apple." They include case studies, such as one on the decision to make iTunes compatible with Microsoft Windows. And then there's Picasso's "The Bull," a striking series of increasingly streamlined images that demonstrate the power of design simplicity. As Chen writes, "Apple may be the only tech company on the planet that would dare compare itself to Picasso."

YawnWaking Up Is Hard to DoMatter

Sleep! There's a lot of research out there on how much to get and why, and on the productivity pitfalls of getting too little. But science hasn’t really focused on that other part of sleep: waking up. Thankfully, Kevin Roose has used himself as a blurry-eyed guinea pig to identify the best ways to rise and shine.

In order to avoid what's called "sleep inertia" — that groggy period of impaired cognitive function after you open your eyes — he tried the following: a regular sleep schedule (eh, didn't really work); the right alarm clock (the Wake-Up Light was a hit, while a scent-based device made his bedroom smell "like a Thai restaurant”); and the R.I.S.E. U.P. method, which involves forgoing the snooze button, increasing your activity during the first hour of being awake, showering, exposing yourself to sunlight, listening to upbeat music, and phoning a friend. In particular, Roose found that scheduling phone meetings for 6:30 a.m. (he works on the West Coast) has a significant effect. And for all you caffeine lovers, he identified cold brew as the best thing to wake up with.

BONUS BITSThat Crazy Internet

I Liked Everything I Saw on Facebook for Two Days. Here's What It Did to Me (Wired)

Just Kill All of the Comments Already (Pacific Standard)

A Tool That Answers 'What's That Typeface?' (The Atlantic)

Can an Outside CEO Run a Family-Owned Business?

Gus, the dad of one of us (Rob), found his dream job. After being head of sales in a large sporting goods company for over a decade, he was ready to move up to a CEO role. A good friend ran a sizeable sports cap company, a family business, and he was looking to step aside. Gus took the job and relocated his family. Eighteen months later he was out and looking for new employment.

What happened?

A son may not always be unbiased about a parent, but Gus was a smart businessman. (In fact, he quickly found a top job in another business.) He had stepped unknowingly into a family business system in which the patriarch was unready, ultimately, to step aside.

Should he have turned down the job? Not necessarily. In our experience, the majority of family owners sincerely supports an outside, competent leader. But every such leader should expect – indeed embrace – intricate family dynamics if he or she hopes to be successful. Often, these dynamics are evident in predictable patterns and sets of behaviors, which we describe below using five archetypes. These are stereotypes, admittedly, but nonetheless real enough that you should prepare yourself to work well with each of them in order to succeed:

General MacArthur. Often the founder who built the company up from nothing, General MacArthur retires with the idea, usually unconscious, that “I shall return.” He or she has no real responsibility for the business anymore, and often has no title or formal position, but his or her passion is still the business. Given that General MacArthur is usually the controlling owner in a family business – legally and/or psychologically – you can’t actually stop him or her from returning, and so you must turn the situation to your advantage. The retiring founder has invaluable experience and expertise, so ask yourself whether there is someplace else in the business where he or she adds real value – e.g., board chair or head of the family foundation. At the same time, you should move to establish a board with strong independent members if one does not already exist. This will help moderate the effect of the General’s reengagement in the business.

The Historian. Just as the boy in the fairy tale who was always crying “wolf,” the historians of the family business world are always crying “family values.” Don’t get us wrong: values are critical and often give family businesses a competitive edge over publicly traded companies. But sometimes all the talk about the past is a cover for something else, typically deep-seated resistance to change. When you encounter this person in your work, try to separate the talk of values from the family legacy, e.g., the story of the founder building the business from scratch, or the history of the first retail story. Values may be immutable, but the legacy can be redefined to allow for necessary changes in strategies and policies. Try to help the family keep alive a sense of history without becoming enslaved to the past.

The Squeaky Wheel. Not uncommonly, there is second or third generation family member who has inherited some shares but who has no direct experience in the business. Typically these people have a core of advisors, mostly lawyers or tax people, who advise them to maximize the value of his holdings, not the company’s overall value. If you encounter a squeaky wheel in your position, then work with the board or shareholder council to provide basic financial education for all the owners. You also need to read the shareholder agreement and to familiarize yourself with the capitalization table, which shows how much the equity owners of a company have, and often how much money they have invested in the company. A dissenting minority shareholder is an annoyance, but if he or she is a majority shareholder, then you could be in trouble. Even if the person is a minority shareholder, you should try to get a sense of whether the majority shareholders are willing to move ahead if someone pulls them in a different direction. Legally, owners may have many options that they’re psychologically unwilling to exercise – e.g., calling a shareholder vote when there is a shareholder disagreement. Forewarned is forearmed.

Hamlet. Sometimes the patriarch or matriarch brings in a non-family CEO (including an in-law) to serve as regent until the adult child is experienced enough to take over the business. Although this is far from universal, we have seen heirs apparent who try to undermine their parents’ choices; this typically happens when there is tension between the parent and the next generation. You must always take young Hamlets seriously because they are the future of the company, and because they are not always quite so indecisive as the Prince of Denmark. They know precisely where the weak links are in the family business system and they can pull at them until the whole chain breaks apart. When you spot an heir apparent, recognize and accept that you are but the bridge to the future. Try your best to educate Hamlet – and make sure going in that you have a good exit package. Your runway is short — three to five years, not ten.

The Wild Child. Tragically, it’s all too common for families – business and otherwise – to have their addicts and alcoholics, and the human toll is inestimable. The price exacted of the business may also be huge. We once had a client where the cousin owned 40% of the company and he had a heroin addiction that commanded the family’s time and attention for more than two decades. The cousin could not stay sober long enough to let the family get down to the work of running the business. If you have a significant owner who is an active alcoholic or drug addict, look to see if the family knows how to manage conflict. Is there someone around to help family members detach with love so that they can keep the family business system operational? If both these things are missing, you should recognize that through no fault of their own the family may be unable to make the necessary decisions to run a business without very great difficulty.

These characters are likely to reveal themselves during your interviews if you are paying attention to the signals. In our experience, the hiring process closely mirrors how the family business systems make (or can’t make) decisions. If you are interviewed only by the founder – or, conversely, if all 300 owners need to sign off before you can be hired – you can probably expect to encounter similar dynamics once you start the job.

One last thing: Try to talk to your predecessor before making your final decision; she can help you figure out the game. Have others left satisfied or frustrated? Are there enough buffers in the system to protect you? If the system is moving forward and making decisions in a positive way, then that’s a good sign that these characters are making positive contributions. If not, be prepared to engage in family dynamics that will challenge and maybe even stall the best laid plans. If a good, even world-class leader doesn’t know what he is up against when he enters an enmeshed family business system, he is unlikely to win. And then everybody loses.

Ferguson Shows How “Tried” Is No Longer Enough

Think of the Chief of Police of Ferguson, Missouri not as a cop, but as a failed leader.

To start, Chief Thomas Jackson no longer has jurisdiction over his city’s security; the Governor of Missouri has asked his state Highway Patrol captain Ronald S. Johnson to take over. This comes after a national outcry against the police response to protests in the aftermath of the shooting on Saturday of 18-year-old Michael Brown.

He failed, and his boss just replaced him. Not surprising. And frankly, to many people, a very small step of many that need to be taken to move forward.

We could view this situation through many other lenses. The venerable veterans of the Civil Rights movement will remind us that all of this has happened before, 50 years ago.

Many would argue as the Economist did back in March of this year: “America’s police have become too militarized.” Others will argue, with far too many facts to support the argument, that America is not for Black people.

The thing I kept thinking about today was how when the Police Chief was asked why his police force was nearly 100% white, he said that his department was “always trying to improve diversity in its ranks.” He claimed, “It is a constant struggle to hire and retain personnel.”

“Race relations are our top priority,” Jackson said. Yet, the fact is that only three of 53 police officers are black in a town that is predominantly African American.

So, the word that struck me was “trying”.

When leaders say they are “trying” but unable to accomplish their goal, what they are really saying is they haven’t made it a priority. They only talk about it. The issue is supposedly important, but then when it comes down to action … it remains perpetually irrelevant. And then these supposed leaders will point to factors involved, like a pipeline issue, suggesting that the problem is outside of their control.

All of this reminds me of the more mundane yet parallel topic of diversity in tech, which has been getting recent headlines. Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, said as they released (their lack of) diversity numbers, “I’m not satisfied”. And while I believe that our corporate leaders, as well as government leaders mean well by their words, I’m struck by how much things remain conceptual goals, not productive actions.

Because – if something is truly important to you – you do something about it.

Let’s remember that leadership is foremost about commitment. After all, leaders decide what we will, and won’t do. Leaders then act on that commitment by how they prioritize and direct a combination of time, energy, focus, and, above all, resources. So whatever this Chief’s stated priorities were, his actions didn’t include a commitment to inclusion.

Is change possible? You might believe that “getting the best talent” means being race- or color-blind. But in reality, it’s an evidence of bias to say you can’t have “the best” and also have people who are different from you. Remember, all of us are biased in some way. Research proves it. It’s only when we recognize it can we address it. None of us drift our way to better behavior. We achieve new outcomes by being intentional and deliberate.

Ferguson is a tragic example signaling why it’s so important for leaders to be intentional about building a team that is different and inclusive. We pay a price when don’t include difference, whether that is women, people of color, the LGBT community, and so on. None of us can say that having a police force that reflected Ferguson would have avoided what has happened this week. But it would certainly have altered the events that followed.

When leadership roles reflect and include the people they represent and their shared purpose, then challenges are “our” problems, not “their problems.” And this is how we get to new outcomes – by seeing something as ours to care for, ours to build, our future to create. Just look at the example already being set by Captain Johnson.

And that’s what it’s going to take to address all the things that Ferguson represents. To see this not as a poor-side-of-town problem, or as a young black man problem, or as any other version of “their problem”… but as our problem to work with one another towards a society that works, where people thrive, and where prosperity rules. Because we’re in this together.

“Tried” is no longer enough. Actually, it never was. We need to expect more from all our leaders.

Why We Don’t Protect Our Passwords

Last week, news broke that a Russian crime ring has stolen 1.2 billion user-name and password combinations, and more than 500 million email addresses—the latest in a long string of data breaches. The experts say the best way to protect your identity and online information is to change passwords regularly and use a different password for every site. Yet according to a survey conducted last spring by the Pew Research Center, only 39 percent of Internet users ever changed their passwords.

As someone who studies consumer choice behavior, I’m always intrigued by statistics like these. Obviously, there is a yawning chasm between what we should be doing and what we actually do. And I’m just as guilty. I have not changed my password despite a one-in-three chance that my computer will be hacked, my credit card abused, my identity stolen, and all the other stuff I do not want to think about. This raises two important questions: why don’t we act in our own best interests, and how can we get better at it?

Being a marketing professor, I have segmented us non-actors into categories of inertia:

The Clueless. These are the people who somehow remain unaware of the need to change or strengthen their passwords. They willfully tune out information that is unpleasant or discomfiting. Academics call this behavior “seizing and freezing”—seizing on a word that makes a person uncomfortable (in this case “hacker” or “password” or even “Russia”) and freezing out any information about it—and it occurs because we have no intention of changing our behavior or associations related to the words in question. The inclination to seize and then freeze on early judgmental cues reduces the extent of information processing and hypothesis generation and introduce biases in thinking.

The Avoiders. Changing your password is a chore, like flossing and saving for retirement—so many of us simply choose to avoid them. Such “avoidant” decisions speak to the all too common choice to think, believe, or feel the consequences are not relevant to me.

The Leaners. These are the people who say “I want to do it” but who don’t follow through, thus demonstrating their “revealed preference”—a fancy term for the idea that actions speak louder than words (or thoughts). When prompted to act, they think up arguments for inaction: If I change my password who’s to say it can’t be hacked again? Or, I am not one of those unfortunates who let bad things happen to them. This is a particularly challenging bunch.

The Procrastinators. These are the people who keep promising to do the right thing but never get around to it. When they declare their intention, they assuage their guilt for not taking care of themselves, appear to be responsible, and avoid incurring the costs of changing their behavior. People procrastinate for a variety of reasons, including “present bias” (where we put more weight on minor immediate costs than major long-term benefits) and “loss aversion” (putting more weight on the costs of changing our password than on the benefits of doing so).

How do we escape our inertia? As people move from inaction toward action they rely on information, commitments, conditioning, contingencies, environmental controls, mindfulness, and social support. I adapted the segments above from a psychosocial model called “stages of readiness,” which in turn offers guidance on this front: The most effective way to stop being “Clueless” is to “raise consciousness” or increase awareness via information and education. “Environmental reevaluation”—or realizing the costs of not changing passwords—can create a path out of the “Avoider” phase. And “Leaners” can benefit from “self-liberation” or believing in their own ability to change and committing to act on that belief. “Procrastinators” should seek support from friends they trust, tell people in order to create more urgency to act.

At the organizational level, we could automatically send new passwords at regular intervals to all account holders on any enterprise system (sigh). Research shows that such defaults, like 401k automatic enrollment, can be used to steer people in beneficial directions without constraining the choices of those who prefer a different option and take the trouble to obtain it. Enrollment in tax-favored savings plans is 50 percent higher when employees are automatically enrolled compared to when they opt-in. Organ donation rates are four times higher when consent to donate is assumed than when it needs to be given explicitly. Food choices are healthier when the default is lower-calorie ingredients.

The second option is to use “enhanced active choice,” a communication technique that highlights the option preferred by the communicator by pointing out the losses incumbent in the non-preferred alternative. In this case, you would get two options: “1) I will change my password to protect my online accounts and other confidential information on my computer, or 2) I will not change my password because I do not mind if a perpetrator has access to my computer and may use my money in horrible ways.” It works regardless of whether you are forced to select one option, or select one option voluntarily (rather than walk away).

Enhanced active choice is best used in situations where there’s evidence that one option is generally superior. Although it may appear obvious, reminding people of what they will lose if they opt for the non-preferred alternative can have a powerful impact because individuals are unlikely to seek out information about the costs of remaining with the status quo when unprompted, especially if such thoughts evoke negative emotions like anxiety and regret. Dislike for the non-preferred alternative will be more marked when the costs of non-compliance are highlighted in the choice format. Accordingly, the objective in enhanced active choice is to shift away from an opt-in, opt-out, or automatic enrollment default option to a more empowering, self-enhancing forced-choice format that bestows control on the decision-maker.

I have used enhanced active choice to increase enrollment behavior in a variety of “ought to” contexts, such as completing a health and wellness assessment, obtaining a biometric screening, getting a flu shot, and in automatic prescription refill programs. This low-cost communication method beats asking people to “opt-in” or “just do it” by at least 30% and in some cases actually doubled enrollment. It works largely because it prompts regret (action) rather than guilt (inaction). And it is less coercive than the alternative.

Of course, all of this activity has to be ongoing. The threat posed by hackers is only getting worse. And once again, the stages of change framework offers a useful reminder: The final three stages are action, maintenance, and relapse.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers