Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1378

August 22, 2014

The Conversation We Should Be Having About Corporate Taxes

The corporate inversion — when a U.S. company takes on the legal identity of foreign subsidiary, usually in order to reduce its taxes — has become about as controversial as corporate finance topics get. President Obama has called such transactions “unpatriotic.” Others have defended them as a way for American companies to stay competitive in the face of a uniquely intrusive tax code.

Harvard Business School’s Mihir Desai and Bill George both fall mostly in the second camp, but with some surprising twists that came out when I spoke with them recently. Desai is a professor at Harvard Business School and Harvard Law School who has done a lot of research on corporate taxes, and wrote the July-August 2012 HBR article “A Better Way to Tax U.S. Businesses.” George is a professor at HBS and the former CEO of Medtronic, which has been involved in one of this year’s highest-profile inversion transactions, a merger with Ireland-based Covidien.

Part of our conversation was recorded for an HBR Ideacast, which you can listen to below. What follows that is an edited, much-condensed transcript of both the Ideacast and the progressively wonkier discussion that ensued after the podcast was done.

Why have inversions become a big deal lately?

Mihir Desai: There was a wave in the early 2000s, and we shut them down with anti-inversion legislation. Now, instead of just being able to do it by yourself, the rules are such that you really have to have a foreign partner and there has to be a merger. As a consequence we now see these relatively high-profile mergers which facilitate the departure of U.S. companies. We have some of our largest and most innovative companies doing this.

So Bill, is the problem here — if there is a problem here — our corporate tax code or our corporate executives?

Bill George: The problem is definitely with the tax code. We have a dysfunctional tax code in the United States. We have among the highest tax rates anywhere in the world, and what’s happened is companies are paying taxes on foreign earnings that they generate overseas but they’re not bringing them back to the United States because they don’t want to pay at the U.S. corporate tax rate of 35%. You’ve got some $2 trillion of cash trapped overseas, so companies are looking for ways to use that cash effectively. It’s driven many U.S. companies to buy foreign companies, but in many cases they’d much rather deploy that cash in the United States.

One very interesting proposal came from Robert Reich, a liberal Democratic economist who recommended that the U.S. go to the system that almost all other industrial nations have of just taxing people where they earn the money. Personally I think that would solve the problem.

Mihir, you wrote an article for HBR a couple years ago on how to fix the U.S. corporate tax code, and I think this was one of the things you wanted to have happen. What were some of the other key changes?

Mihir Desai: This is the manifestation of two big problems. One is a high rate, and the second is this worldwide system, both of which are highly distinctive relative to the rest of the world. One of the things that’s happened recently is that leading countries like the UK and Japan, which used to look more like us, with relatively high rates and a worldwide system, have left. So now we’re really all alone — and that’s why these transactions are happening more.

A meaningful reform would combine two things. One, a considerably lower rate — and I think you need to get below 25% or 20% for it to be meaningful. And the second, as Bill mentioned, is a switch to a territorial regime. I actually am optimistic that we can get there; there’s a fair amount of consensus about that. The tricky part is where does the money come from to fund all of that, and there I think people divide up. My proposal has two particular sources of revenue-raising: One is that we have now large numbers of pass-through entities, and we have more business income in non-C-corporate form than we do in C-corporate form.

Like what kind of entities?

Mihir Desai: Those would be partnerships, those would be REITs, those would be subchapter S corporations — LLCs — and they have mushroomed wildly in the last 25-30 years. As a result the only people who pay the corporate tax are these large public multinationals, and that doesn’t make any sense. A small tax on those pass-through entities can help a lot. The second source of revenue is trying to change the fact that corporations report large profits to the capital markets and relatively small profits to tax authorities. If we make it more the case that you have to base your taxes on profit reports to capital markets, that can raise a fair amount of revenue as well.

Bill George: One issue I fear is how much money is going to be lost by the U.S. Treasury. When I’m talking to corporate CEOs, CFOs, and board members, I don’t see the major multinationals planning to bring that cash back to the United States. I was with the CFO of Apple the other day, and they’ve got $140 billion of cash trapped overseas. They aren’t planning to do an inversion, but on the other hand after tax they’re earning less than 1% on that money, compared to over 30% when they invest it in new products and R&D and innovation.

Mihir Desai: The amazing thing about Apple is they just decided to give back a lot of that cash in the form of dividends and share repurchases, but to fund it they’re not bringing the cash home from Ireland, they’re borrowing close to $40, $50 billion. Tim Cook in his testimony to the Senate committee said should I borrow money at 1% or should I pay 35% on my repatriated profit? The answer obviously is borrow at one.

One percent vs. 35%, that’s a really big difference. But at some level is there a conflict here, if you’re a CEO of a company — and you were one, Bill — between your obligation to your shareholders and others within your organization to minimize taxes, but then also your obligations as a citizen to not minimize them all the way to zero. What is the dividing line here? Is there one that we can identify?

Bill George: I’ve just spent many hours talking to Omar Ishrak, the CEO of Medtronic, who is involved in a major inversion, a $43 billion deal to purchase Covidien. The key question I asked him was, “Why are you doing this?” If he’s doing it for tax inversion, he’s got trouble. But he was very clear he was doing it to expand the Medtronic mission of helping patients — the strategy is a perfect fit, and it allows them to invest more money in innovation, ironically, because they can now use the $14 billion they have in cash trapped overseas to invest in the U.S.

You’ve been critical of some of the other inversions, such as the Pfizer one which isn’t going to go through.

Bill George: I was quite critical of Pfizer because I thought they were doing it for the wrong reasons. In fact Ian Read, the CEO, in his testimony to the British parliament, said he was doing it basically for two reasons, one for tax saving through the inversion and on the second to do all the savings he could by cutting people and combining. So I saw that in a very different context.

Back to the Medtronic example. Medtronic gets no tax savings. It already has an 18% tax rate and that’s about what they’re going to pay with Covidien. So there’s really no savings to them at the present time, but it does free up cash.

Mihir Desai: Bill’s example is interesting for two reasons. One is that we’re in such a crazy place that doing something that seems like it’s going to remove activity from the U.S. actually helps the U.S., because of all this capital that’s trapped overseas.

At the same time I do think your question puts your finger on something deep, which is there’s a growing distrust of corporations. When people see corporations doing this, they question their patriotism, as in fact the administration has. Corporations have to be more sensitive to this issue than I think they’ve been.

Bill George: There has been a lot of ill will over that and I think companies are going to have to step up and show their commitment to invest in the United States. Because this is the greatest place anywhere in the world to invest in innovation and R&D. As well as investing in social programs through their own philanthropy — I think many companies are stepping those up as well.

There is this argument from at least a minority of economists that the corporate tax is an abomination anyway, that we should just be taxing the shareholders — as we do, although right now we give them a lower tax rate — and not corporations. Do either of you think there’s any merit to that argument?

Mihir Desai: Well, yeah, I think there’s a fair amount of merit. And I don’t even know if it’s a minority. The corporate tax is a hard tax to like. It’s a hard tax to like because it’s a second layer of taxation and it’s entity-level taxation. So it’s always going to be dominated by a tax on individuals, because you’re giving another margin for distortion and another margin for evasion.

The reason why we might still like one, albeit it a low-rate one, is because without it you can run into some problems with individuals shielding and hiding their own income. Justin Fox Inc. can all of a sudden become a vehicle, if it’s got a zero rate, for shielding a lot of income. So we need a rate, and it’s probably positive.

One thing that’s really striking is how consistently, in polling, Americans of both parties, of all age groups, agree that the one group in this country that needs to pay more taxes than they do now is corporations.

Mihir Desai: It’s a puzzle. We know that corporations don’t per se pay taxes. That tax is going to be borne by shareholders, workers, or customers. Those are the only people who can actually end up paying the tax. So while people like to think about corporate tax reform as a sop to big business, the reality is that what we know about the corporate tax is it’s most likely borne by workers.

When you say it’s borne by the worker, you mean it comes out as lower wages?

Mihir Desai: Exactly right. It’s either the shareholders, the workers, or it’s going to be customers. And those other folks are pretty mobile. The workers aren’t.

Bill George: Just to illustrate that with an example. I serve on the board of Exxon, the world’s the second-largest market cap company. It’s very profitable. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. Exxon pays 45% tax on a global basis. Of course it affects dividend policy, it affects wage policy, it affects everything.

The real issue in our tax code is we’ve got a huge number of loopholes and a lot of favors given to various industries, and if we were to go to territorial tax system I think there’s a golden opportunity to get rid of a lot of these loopholes.

When you talk about loopholes, the reason why Apple and Google, they’re the most famous ones, have these massive piles of money overseas is because it’s income that they’ve paid almost no taxes on to any country at all. One of the questions is if you went to a territorial system and you didn’t fix these Double Irish Dutch tax sandwiches or whatever it is that they use to move income around, aren’t you just opening the door for a huge amount of abuse?

Mihir Desai: Let’s take Apple as one concrete example because the facts are relatively public. There’s $140 to $160 billion of offshore cash, $100 billion of it is in Ireland. Almost all of that $100 billion represents not profits earned in the U.S. but profits earned in Germany and Japan or China or wherever and then potentially shifted to Ireland. Do we care if Apple shifted money from Germany to Ireland? Frankly it’s not clear to me why the U.S. taxpayer cares about that. The German taxpayer should care about that, and the German taxpayer should be worried about it, and they should go after Apple if they want to. But why are we in the business of defending the German taxpayer?

Bill George: The one area the IRS and the Treasury would have to be very analytical and consistent on is transfer pricing. If companies are going to move technology ownership outside the United States, then you pay a substantial tax on that. That should be enforced. If you make products in the U.S., some of the profits should be captured in the U.S.

Let me give you specific example. Back in 1996, Medtronic made an arrangement to put a major defibrillator factory in Switzerland. The technology was all created in the United States, so what Medtronic did was sell that technology from Medtronic U.S. to Medtronic Switzerland, and pay a very substantial tax on that in the United States. After that it was governed by the Swiss tax system in terms of the profits made where manufactured.

With these companies where everything is intellectual property, and there aren’t factories moving from one country to another — Google is the really clear example of that — the tax authorities of the world seem to be struggling with how to do this correctly.

Mihir Desai: Absolutely, and one of the interesting things that’s on the horizon is the OECD has something called the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative. They’re trying to come together and get at this idea of how does intellectual property get transferred and how do we value it. That’s a non-trivial problem.

The question politically is do we really think we’re going to get to a place where we have a multilateral organization, like the WTO, in taxes. I think the answer to that is, highly unlikely. That’s just a bridge too far for most people.

Bill George: You’re now getting into a much broader and more complex issue. With global corporations, they have to insure that they can be competitive around the world, and still be responsible to the national governments they serve. And there’s no such thing as global laws in many, many cases, including tax law. So you get a great deal of dysfunctionality, and I think this is why we need international bodies to help us work our way through these issues and sort them out.

August 21, 2014

How to Stop Corporate Inversions

Bill George and Mihir Desai, professors at Harvard Business School, explain why our corporate tax code is driving American business overseas.

Publishing Is Not Dying

If marketers want to produce content, they need to think like publishers. After all, content isn’t an extension of marketing, it’s an extension of publishing.

I am hardly the only one to make that case, but skeptics are still vocal in their disagreement. “Aren’t publishers failing?” they say. How can I hold up a struggling industry as a model? If publishing is a viable model, why aren’t publishers making money?

These sentiments are common, but they are not based in fact. In truth, publishing is flourishing, creating massive new fortunes for entrepreneurs and more choices for consumers. It’s also attracting large investments by established companies and venture capitalists. Though not everyone prospers, there has never been a better time for publishers.

First, the obvious: a new breed of online publishers has been generating hundreds of million dollars of value in very short periods of time. “Mommy blogs” created an entirely new category. Bleacher Report was sold for over $175 million in just five years. The Huffington Post was sold for $315 million in just six years. And it’s not just the financial results that are impressive — Huffington Post has won a Pulitzer Prize, as has Politico, a news organization launched in 2007.

These examples are not mere exceptions, but part of a growing trend. Publishing start-ups are hot. Vox Media, a venture-funded publishing start-up, recently lured Ezra Klein away from the Washington Post. Andreessen Horowitz just announced a $50 million investment in Buzzfeed. ESPN recruited Nate Silver to run his famed data journalism blog, FiveThirtyEight, under its umbrella. Clearly, there’s no shortage of opportunities in online publishing.

Sure, you may say, tech-savvy startups are doing great, but old-line publishers, like magazines and newspapers are doomed. Aren’t they?

It’s true that magazines in the U.S. were more profitable in the pre-digital age because of the fragmented broadcasting market, but they do make money today. Magazine consultant Jay McGill estimates that profit margins in the industry have dropped off from a stellar 20–25% to a more earthly, but still healthy, range of 12–15%, which is pretty close to the average for the S&P 500. In fact, publishing giant Hearst recently reported record-breaking ad sales for its September issues.

Samir Husni, Director of the Magazine Innovation Center, also points out that in recent years publishers have taken concepts from other media platforms, like All Recipes, HGTV, and Food Network, and turned them into successful print brands.

The newspaper industry has been hit especially hard because historically it has derived much of its revenues not from display advertising, but from classifieds and other direct marketing services, where the impact of digital technology has been the greatest. So it shouldn’t be surprising that many newspapers have struggled. However, even here the story isn’t as bleak as many think. Last year, News Corp’s newspaper division reported EBITDA of $795 million on $6.7 billion—a 12% margin—which is pretty good. Even The New York Times—which, as I’ve noted, has not run its business well—achieved 8% net margins in 2013—not great, but not exactly a tragedy either.

The reason why many publishing businesses continue to make money is simple: they’re selling a product that people want and need. As long as people want to be informed, entertained, and inspired, there will be profitable opportunities in publishing.

Yes, some old-line publishers are faltering and clearly there are challenges ahead, but that can be said about any incumbent industry. We live in an age of disruption, and in order to compete, everyone must adapt. You simply can’t run a business—any business—the way you did 10 or 20 years ago.

Still, the future of publishing is bright. While every business needs to adopt a true culture of change, clearly there is no lack of potential. Once you accept the fact that business models don’t last, it becomes clear that there are, in fact, more opportunities to create and curate content, access top talent, attract investment, and make money than ever before.

The key is for publishers to stop trading digital dollars for analog dimes. Take web video, for example, which is booming. Print and digital publishers have long complained about the abundance of ad dollars that went to TV. Now they can compete for budgets against even the strongest broadcasters on a variety of platforms. In fact, online video revenues are growing at 20% per year.

Beyond that, there is mobile, e-commerce affiliate programs, social media, big data, and the fact that it is easier to experiment with and develop new content on digital platforms than it ever was in the physical world. Once publishers let go of the idea that they are going to make their money selling ad pages and pushing rates, it become clear just how profound the opportunities are.

So there is no intrinsic problem with publishing. There is still enormous value in uncovering stories and telling them well. That publishers need to innovate their business models just puts them in the same place as every other industry.

Publishing is dead? Hardly. In fact there have never been more opportunities for publishers.

Online Shopping Isn’t as Profitable as You Think

When I argue that e-commerce isn’t likely to destroy innovative omnichannel retailers, I typically receive passionate responses. Am I really suggesting that the growth of e-commerce will slow before it annihilates most physical retailing? And how could I possibly argue that the economics of omnichannel retailers are as favorable as those of pure-play e-tailers?

Growth rates first. Several organizations track e-commerce sales, including the U.S. Census Bureau, ComScore, eMarketer, and Forrester. All show similar trends. For example, Forrester’s data on the top 30 product categories (which account for 97% of total e-commerce sales) indicates that e-commerce growth fluctuates with economic conditions but is clearly slowing overall:

This is a familiar growth pattern: E-commerce as a percentage of total retail sales seems to be following a classic S-shaped logistic curve. If historical trends continue, e-commerce’s share of retail will rise from 11% today to about 18% in 2030, albeit with big variations by category.

Of course, that pesky “if historical trends continue” phrase generates ferocious debates. What if e-commerce creates such enormous economic advantages that physical retailers simply can’t compete?

E-commerce companies, like physical retailers, have wide-ranging cost structures and financial results. In general, however, e-commerce operations aren’t as cheap to run as most people think. Their economics greatly resemble those of mail order catalogs—in fact, many e-commerce businesses continue to use catalogs in their marketing mix—and they aren’t all favorable. Amazon, whose results are similar to those of other e-commerce companies and divisions, has averaged only 1.3% in operating margins over the past three years. Operating margins for department, discount and specialty stores typically run 6% to 10%. Lower margins can come only from lower prices or higher costs.

“Ah,” you might say, “Amazon does have lower prices, and its costs are higher only because it is investing so heavily in growth.” But how much of the difference do these reasons explain?

Price comparisons are always tricky: they are complicated by the basket of items selected, how promotions and coupons are treated, the handling of loyalty program rebates, and many other variables. But Amazon’s prices aren’t uniformly lower than competitors’. One recent Kantar Retail study of 59 items found that prices at Walmart’s Supercenter stores were 16% below Amazon’s. Another study, by William Blair & Company, found that prices at several physical retailers are about 10% below Amazon’s on items costing less than $25. In cases where store-based retailers do charge higher prices, several I have spoken with calculate that closing price gaps with Amazon would cost them between 1 and 3 percentage points of operating margin. That would still leave them with 2 to 8 points of margin advantage.

But what about the economics of e-commerce orders? Even there, creative omnichannel retailers aren’t necessarily at a disadvantage. E-commerce companies ship to customers from large, expensive, highly productive fulfillment centers. (A state-of-the-art center can cost $250 million or more to build, or about 10 times as much as a big box store.) Fewer fulfillment centers mean lower capital expenses but higher shipping costs and slower deliveries. Meanwhile, omnichannel retailers already have hundreds or thousands of distribution centers called “stores.” It costs only about a dollar more to pick an order from store shelves than from automated warehouses, and the proximity to customers saves at least as much in shipping costs—especially for in-store pickups, rapid deliveries, and returns.

It’s true that rapidly growing e-commerce companies like Amazon have been investing heavily in their future. Still, market maturation often forces sustained expenditures just to hold ground. For example, as Amazon builds fulfillment centers in more states, those states are now forcing it to collect sales taxes—an effective price increase of about 7% on average—and researchers at Ohio State University say that reduces spending on Amazon by about 10%. Substantial investments in price or differentiation may be required to offset such effects. Several public e-commerce companies are already experiencing reduced growth and margins as competition intensifies.

A common argument is that rapidly evolving digital technologies will increase e-commerce’s advantages. But retailers who fuse the best of digital and physical technologies—we examined these “digical” innovations in an article in the September issue of HBR—can capitalize on digital advantages both online and in stores. Digital technologies will improve in-store visual merchandising, help customers choose the type of service they prefer, speed checkout times, customize offers, and provide virtual connections to global experts or trusted friends. Radio frequency identfication (RFID) tags will improve in-store fulfillment speeds. Automated backrooms in supermarkets will pick and pack commodities while customers hand-select their favorite produce and meats.

I’m not underestimating the magnitude of the changes physical retailers must implement. But digical strategies combining the best of both worlds will be more attractive to a broader range of customers while enabling superior economics. Perhaps this is why even Jeff Bezos has said that if Amazon can find the right idea, “We would love to open physical stores.”

Why Going All-In on Your Start-Up Might Not Be the Best Idea

Entrepreneurs who give up their day jobs in stages are 33% less likely to fail in their start-ups than those who leave their jobs precipitously to run their new businesses full-time, according to a study of thousands of Americans by Joseph Raffiee and Jie Feng of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The staged approach, which allows entrepreneurs to gain important knowledge about their new businesses while phasing out their paying jobs, has become much easier with the rise of digital technologies that reduce the cost and time commitments of starting new companies, the authors say.

Why Marketers Want to Make You Cry

“Hey – Dad? You want to have a catch?”

Every time I watch Field of Dreams, there’s one scene that gets me. When Kevin Costner’s character asks his ghost father to throw a ball around, I – and a lot of other guys my age – dissolve.

Chances are, the stories that stay with you also make you cry – or laugh – or get angry. The strong emotions make them memorable.

Marketers are getting increasingly sophisticated at tapping into those strong emotions, and they don’t need a full-length feature film to do it. How many of you teared up – be honest – when you watched this heartwarming P&G commercial during the Olympics?

So how do marketers go from 0 to tears in 30 seconds?

In a word, storytelling. From drawings on cave walls to blockbusters at Cannes, story is still the most powerful way to elicit an emotional reaction. Realize, however, that these emotional connections don’t always have to be innately positive. Chipotle’s “Scarecrow” video, which now posts 13 million+ views, evokes a number of downright depressing emotions by telling a simple story designed to educate consumers about today’s food preparation and make them feel better about Chipotle as a better choice. Nevertheless, the story does end with a challenge to consumers, encouraging them to be part of the solution and to “cultivate a better world.”

The difference between any particularly emotional story and a good marketing story is that a marketing story has a purpose. Ask yourself, “What is the objective of the brand story?” Is it to educate potential fans about some aspect of the brand – like Chipotle’s more sustainable supply chain? Maybe it is simply to bring the brand’s personality to life. (After all, no matter how touching the commercial, no brand can actually be the “sponsor of moms” – yet P&G clearly positions its portfolio of brands as exhibiting mom-like qualities.) Regardless, having a clear, concise rationale is critical before creating your story. Storytelling is simply the means to the end. It is our responsibility to understand what that end is.

Great emotional stories also need to evolve to change with the times. The message may be the same, but the story evolves. For instance, during the 2014 Super Bowl, the Coca-Cola Company ran an ad that showed the various aspects of today’s culturally diverse America with the hymn “America” sung in different languages.

The theme behind the story was the same message the Coca-Cola brand communicated forever – authenticity, sharing happiness, and Americana. What changed was the way these ideas were communicated. Coca-Cola has evolved to communicate these ideas in a 21st century way that is aligned with our times and as a result, shows that Coca-Cola isn’t an outdated brand. By modernizing its stories, Coca-Cola is avoiding the mistake too many mature brands often make. All too often, mature brands believe that they have to change the brand’s core message when in fact, the core message doesn’t need to change, but the way the story is communicated does. After all, even though times change, our emotions don’t.

Strong emotional stories also have the power to announce a major brand change. A classic brand, A1, uses a story based on a modern communication platform to share a transformation – modifying its name and, ultimately its positioning from “A1 Steak Sauce” to A1 “Original Sauce.”

Here is a story that elicits real emotion – and yet we’re talking about the emotional life of a steak sauce! Yet, it leverages the classic “boy gets girl, boy loses girl” relationship story that tugs on your heartstrings and yet achieves the purpose of letting the consumer know that A1 is for more than just steak.

Great emotional stories can also make a competitive argument about product features null and void. Apple’s competitors always want to talk about pixels and price points. Apple responds with a story that shifts the conversation to a higher emotional place – and makes those competitive arguments seem small and unimportant. In its heartwarming Christmas story, the Apple brand becomes an integral part of a family’s holiday festivities and thus, takes a higher road against those competitors who want to compare product attributes.

Great emotional storytelling doesn’t take stunning cinematography or a complex storyline. Sometimes it’s as simple as finding the right music. Consider another example from Apple — this simple 2012 iPad mini commercial, which uses a classic Hoagy Carmichael song to create an instant emotional bond with the viewer:

As a marketer, you have to ask yourself, what is our brand’s story? If you don’t know the answer to that question, or even worse, find that it one that isn’t compelling to you, you can be sure that it won’t make customers feel anything.

August 20, 2014

Fixing a Work Relationship Gone Sour

Sometimes you get stuck in a rut with someone at work — a boss, a coworker, a direct report. Perhaps there’s bad blood between you or you simply haven’t been getting along. What can you do to turn the relationship around? Is it possible to start anew?

What the Experts Say

The good news is that even some of the most strained relationships can be repaired. In fact, a negative relationship turned positive can be a very strong one. “Going through difficult experiences can be the makings of the strongest, most resilient relationships,” says Susan David, a founder of the Harvard/McLean Institute of Coaching and author of the HBR article, “Emotional Agility.” The bad news is that fixing a relationship takes serious effort. “Most people just lower their expectations because it’s easier than dealing with the real issues at hand,” says Brian Uzzi, professor of leadership and organizational change at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management and author of the HBR article, “Make Your Enemies Your Allies.” But, he says, the hard work is often worth it, especially in a work environment where productivity and performance are at stake. Here’s how to transform a work relationship that’s turned sour.

Recognize what’s happening

Relationships in need of repair don’t all look alike. David says there are two ends of the spectrum when it comes to relationship problems. You may be in a rut (what she calls “over-competent”) where you don’t go beyond the, “Hello, how are you?” every day. Or on the other side of things, you may be what she calls “over-challenged,” where “you’re always walking on egg shells or constantly not seeing eye to eye.” Take note of what’s happening in your relationship so you know what needs work. “What I sometimes see is a lack of information sharing, or both parties start to keep track of reciprocation. Another symptom of a failing relationship is that people will bring in third parties to confirm their suspicions about the other person,” says Uzzi.

Give up being right

Getting a relationship with a coworker back on track may require that you put your ego away. “We often get stuck in our heads about who’s wrong and who’s right. And when you’re hooked on the idea that you’re right, you can’t start to repair the relationship because the issue of who’s at fault becomes a distraction,” says David. To satisfy this need to be right while not letting it affect how you interact with the person, David suggests “imagining the other person with a big, fat sticker on his back that says, ‘I’m wrong.’” Then you can just focus on moving the relationship forward.

Look forward, not back

Resist your tendency to analyze every detail of what’s happened in your relationship. Who said what? Why did they say it? This isn’t productive. “Lots of people think that it’s only by understanding the past that we get beyond it. But what you focus on is what grows,” David says. So think about what’s worked well previously, what you like about the person, and what you want from the relationship. “Take a solution-focused approach, not a diagnostic one,” she says.

See the other person’s perspective

Empathy is the foundation of healthy work relationships. David suggests you make room for emotions like curiosity about and compassion for your coworker by asking yourself a series of questions: “How does she see things? Is he feeling embarrassed, put upon, misjudged, or misunderstood?” But don’t assume you can just guess how the other person feels. You need to ask, too. “What seems unquestionable to one person might be totally different from the other person’s perspective,” says David.

Find neutral ground — literally and figuratively

When you approach the other person, be sure it’s on neutral territory — not at one of your desks. Instead, go out for lunch or coffee. The physical place is important but so is the emotional one. Instead of debating what went wrong and who is at fault, try to create a space where you’re aligned. It can be helpful to focus on the bigger picture — a common goal you share or a larger entity that you’re both subjected to (think: The Man). “You’ll then begin to build a sense that you’re in it together,” Uzzi says.

But don’t expect the relationship to change overnight. David explains, “The real shifts in relationships happen less in those watershed moments and more in your everyday actions.” Sitting down and talking is helpful “but that’s not where the work really happens. It’s more subtle than that.” Make an effort to change the tone of your everyday interactions.

Reestablish trust and reciprocity

Don’t try to convince the other person that you’re trustworthy with rational arguments. Show it instead. One smart way, Uzzi says, is to “offer things to the other person without asking for anything in return,” he says. This will activate the law of reciprocity and restore the give-and-take of your previous relationship. But don’t verbalize what’s taking place. “That will get you into the tight accounting system of who’s doing what for whom,” warns Uzzi. And be sure to keep your word. “Being true to the things you’ve offered will continue to deepen the relationship and make sure it doesn’t slip back into mistrust,” he says.

Involve other people

Chances are when the relationship went sour, you turned to other people for advice and commiseration. Your attempts to repair the relationship won’t be successful if those people aren’t involved. “Bad relationships regularly involve third parties and you need to get them on board to repair it and keep it healthy,” says Uzzi. Explain to your confidantes that you’re working on the relationship and that you’d appreciate their support in making it work.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Restore trust by offering your coworker something he wants or needs

Talk about your relationship on neutral ground

Make subtle shifts in how you act toward your colleague — this is where the real change happens

Don’t:

Get stuck on who’s right and who’s wrong — focus on moving the relationship forward

Assume that things will change immediately — repairing relationships can take time

Forget to involve people in your network who may have heard you complain about the other person

Case study#1: Find a common purpose

Rachel Levitt* had an ongoing conflict with her coworker, Pia*. At the consultancy where they worked, it was Rachel’s job to sell projects to clients, but it was Pia’s role as the business director to vet the sales proposals and pricing. Pia regularly increased the prices that Rachel was pitching and as a result, Rachel lost potential sales.

Because she didn’t know Pia personally (she had only met her once at a team retreat), she went to her boss, the regional manager. “She told me that she trusted Pia’s judgment implicitly and that I just had to find clients who were willing to pay the premium price,” she says.

The circumstances were starting to affect Rachel’s morale not to mention her sales performance. One day after getting an email that she’d lost yet another potential sale, she called Pia up. Rather than criticize her, she explained the impact the situation was having on her: “I wanted to let her know that I really couldn’t keep working like this, bringing in clients and losing them again and again.” Pia was receptive to what she had to say: “She heard me out and said she wasn’t aware of how she was coming across.” It turned out that Pia was also frustrated by the lack of sales and her performance too was being affected. “This gave us a common purpose to address,” Rachel says. So the two women then switched into problem-solving mode. “She taught me how she did the pricing and we reached a compromise on what could be quoted,” she says.

Pia and Rachel ended up closing several big deals working together. “We weren’t best buds but we didn’t have any further disagreements either,” she says. Both women eventually left the company but they still keep in touch.

*Not their real names

Case study #2: Choose a neutral environment

While Zachary Schaefer was finishing his PhD in Communications at Texas A&M, he took a job teaching classes at a community college in Central Texas. At first, he got along well with the woman who ran the department, but soon their relationship grew tense. “We had very different pedagogical approaches,” he says. “They were teaching public speaking by reading off PowerPoints and I didn’t want to use PowerPoint at all.”

One day, after leading a three-hour class, he stopped by her office and tried to explain how he was feeling. “I told her about my issues and she didn’t like what I had to say. But it was bad timing and a poor choice of location. It was 9pm at night and I was already in a pretty negative mood,” he says. They continued to snap at each other over email and in faculty meetings.

Finally, Zachary decided that he wanted things to change. “I knew I would need to acknowledge how I was contributing to the situation,” he says. But he decided to do it differently this time. “I said let’s go off campus and get a glass of wine or a cup of coffee,” he says. Choosing a neutral environment changed everything: “We were able to take off our professional masks and build some true rapport.”

Zachary explained how he was feeling and asked her how she was seeing the situation. She explained that he was shaking things up and that it had upset people — including her. “We had made some assumptions about each other that weren’t true,” he says. “She assumed I was arrogant and I assumed she was trying to micromanage me. But she really wasn’t. She was doing her job.” He told her that he was not trying to tell her how to run the department but he wanted freedom to teach his class as he saw fit. “We left that meeting understanding that we have different ways of doing things but that we both get them done effectively,” he says.

The working relationship improved and he worked at the college for several years after that. Some of their colleagues even commented on how the two of them had been able to turn things around.

How Google Has Changed Management, 10 Years After its IPO

Google went public 10 years ago today, and since then has dramatically changed the way the world accesses information. It has also helped shape the practice of management. Staying true to its roots as an engineering-centric company, Google has stood out both for its early skepticism of the value of managers as well as for its novel, often quantitative approaches to management decisions. Along the way it became famous for its reliance on exceedingly difficult interview questions — later abandoned — and its “20% time” policy — reportedly on its way out.

In honor of the company’s milestone, here’s a reading list of some of the best things we’ve published on the company since its founding in 1998.

How Google manages

If you only read one piece, make it this one by David Garvin in 2013, on how Google sold its engineers on management. (You can listen to Garvin interview Google manager Eric Clayberg in our podcast if you’d prefer.) Also from the Garvin piece, here’s what getting feedback at Google looks like.

The company faced a challenge in convincing its employees that management was actually valuable. To do so, it had to come up with a brand of management all its own, centered around “people analytics,” a quantitative approach to hiring and operations.

Earlier this year, Google’s SVP of People Operations, Laszlo Bock, wrote about its latest “people analytics” experiment. gDNA is a longitudinal survey of Google employees on everything from happiness to teamwork to office layout. Results will take years to collect, but Bock offers a window into the company’s quantitative approach to management and shares some stats on work-life balance at Google.

20% time

From early on, Google employees were encouraged to spend a significant portion of their time on interesting side projects, with the idea that some of these projects would become new products. Both Gmail and AdSense, the company’s ad software for publishers, started out as 20% time projects. But back in 2010, Chris Trimble criticized 20% time both for being expensive and for emphasizing ideas over execution. Writing last year, amid reports that the company was ending the policy, Michael Schrage took a slightly different view, arguing that 20% time is great for some employees but not for others. As for deciding who gets it? He suggested letting the data decide, an approach Google could no doubt get on board with.

How Google innovates

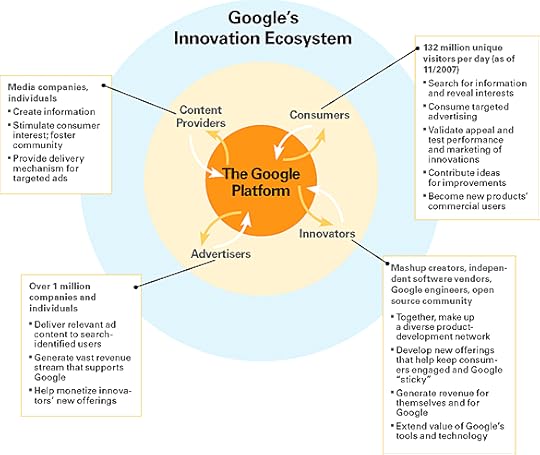

Bala Iyer and Tom Davenport attempted to “reverse engineer” Google’s innovation machine in 2008. The first step to innovating like Google, they argue, is patience. Not just a long-term outlook, but the investment that goes with it to set up the infrastructure — technical and managerial — that makes innovation possible. From there, the authors offer advice including building innovation into job descriptions, and trusting users to inform product strategy.

This emphasis on organizational structure comes up again in a 2014 piece by Linda Hill, Greg Brandeau, Emily Truelove, and Kent Lineback that looks at Google as an example of innovating continually over time. Key traits of innovative organizations like Google include the ability to learn from experiments and to combine “disparate and even opposing ideas.”

In 2011, Rita McGrath echoed another one of Iver and Davenport’s points: the importance of failure. In her post, McGrath recaps 11 product failures by Google over the years to emphasize the importance of taking such risks.

Another look at part of Google’s innovation strategy comes from a 2013 piece on DARPA, the government research agency. The authors are ex-DARPA leaders now running an innovation group at Motorola Mobility, which Google acquired in 2012. At DARPA and now at Google, the authors are focused on the rare form of innovation — described below as “Pasteur’s quadrant” — that simultaneously expands scientific knowledge and seeks to meet a specified societal need.

What Google could do better

Not everyone is so enthused. In 2011, Joshua Gans used Google+ to argue that the company was now playing catchup in key areas. In 2008, Scott Anthony surveyed Google’s innovation track record and concluded that its new products mostly hadn’t delivered results, and therefore Google was still fundamentally a search advertising company.

Eric Schmidt and “adult supervision”

Another management legacy associated with Google is the idea of bringing in an older executive to rein in young founders. Google wasn’t the first example (see: Apple) but the meme is closely linked to former CEO Eric Schmidt’s role at the company. In 2011, Julia Kirby argued that such arrangements will increasingly become common, while Michael Schrage made the case that they emphasize the wrong things about running a business.

Schmidt himself recounted part of his experience at Google in a 2010 article, which describes at length the company’s “quirky” Dutch auction IPO. And when he eventually left the CEO role, HBR editor-in-chief Adi Ignatius recalled past interviews with the founders as evidence of the inevitability of his departure.

Business in the age of Google

Google hasn’t just changed management by virtue of its own practices. Its very existence has dramatically changed the way lots of companies do business. A 2009 piece by Andrei Hagiu and David Yoffie asks “What’s Your Google Strategy?”, and describes tactics firms can use to succeed in an online world dominated by powerful platforms.

Glass, and where Google goes next

Lately, lots of talk about the company’s future has revolved around Google Glass. James Wilson explained last year why he doesn’t think Glass is the future of wearables. Earlier this year, Michael Schrage used Glass as a case study of how not to roll out an innovative new product. And I wrote about the tension between Google’s core strategy as a consumer technology company, and Glass’s potential as an enterprise product.

That’s just a sampling. A look through our archive confirms the outsized role that Google has played in defining what an innovative company looks like. More has been written about the firm than anyone has time to read, but thanks to the company’s eponymous search engine it’s all easy to find.

How to Present to a Small Audience

It’s easy to associate delivering presentations with standing in front of an audience and gesturing toward projected slides. However, many meetings or pitches involve fewer than ten participants in a room, where everyone remains seated and walks through the same slide deck together. This is quite a different scenario with greater constraints on the presenter and fewer tools to engage the audience. But thoughtful planning and awareness of nonverbal cues can make these “non-presentations” successful.

When preparing for a seated presentation, certain tools like a lectern, projector, or microphone may not be readily available, as they might if you were presenting in front of the room. Shift your focus by asking yourself these five questions:

How do you prepare your printed deck? It is important to work from the same printed deck (with the same page numbers) as the audience. When you assemble your deck, use a limited number of handwritten notes (possibly even in light pencil), so you don’t appear overly reliant on them. One colleague shared that when she had forgotten her own deck the pitch went particularly well. She had more of a conversation when she wasn’t bound to her script. If you can’t project your slides, bring a set with you on a USB stick, or email a PDF to yourself as a backup.

How do you prepare the deck for your audience? Make it easy for people to follow what you’re saying by guiding them directly to each slide. Use highlights or sticky notes to emphasize important sections. Or try purposefully leaving something blank that you wish to have the audience fill in. My first sales job was in grad school selling advertising on a desk blotter that was given to college students. My mentor showed me that if I provided a “mini-mock up” of the calendar and quoted the prices to prospective advertisers, most of them would write down the prices as I spoke. When they later looked back at the document, with their own handwriting on it, it formed a more lasting impression.

What else should you bring with you? Since typically every member of the audience will have their own copy of the deck, I try to bring one item that everybody will look at together for at least a portion of the presentation. One group of executives I trained from Rabobank in the Netherlands had to deliver an update to senior leaders on their three-week fact-finding trip in California. Rather than print a small map of the state in each person’s deck, they instead unfolded a large AAA roadmap in the middle of the conference table and marked it up as they went through the presentation, showing the various stops on their trip. Clients of mine who work in architecture or real estate development often bring a floor plan and several sheets of clear acetate when reviewing building or site plans, so the decision makers can sketch what they hope to see in the next iteration.

When should you stand? Nonverbal experts agree that if you can stand, while others remain seated, you gain some power. So decide if you can stand for the more formal portion of the pitch and then sit to field questions. Should this prove too awkward or out-of-the-norm, consider standing for only a few moments. Perhaps stand to illustrate something on the whiteboard or flip-chart, then remain on your feet for a bit longer, as you facilitate some comments about what you’ve just illustrated.

Where should you sit? Seating should not be accidental. If you are the primary presenter, take a position beside or at a corner adjacent to the decision-maker. Research shows that if you share a corner or side of the table with the decision-maker, it will be easier to reach an agreement. Conversely, the most adversarial position (think of a chess game) is directly opposite someone. Try to sit where you can maximize eye contact. Sitting near the end of a long board table lets you easily see the majority of the people in the room (and avoids the tennis match position where you must turn your head whenever a person speaks from each end of the table). Choose a seat that minimizes the barriers between you and the audience. In a room where you regularly present, you may readily know which seat provides you the greatest nonverbal advantage; in an unfamiliar space, you have to quickly decide what’s the best option. When you are on a team for a presentation, enter the room in a way that allows the person with the greatest speaking role to select her/his seat first.

When should you distribute the pitch book? Delay this if possible. Take some time to talk about the audience’s goals and hopes for the meeting before you begin. Once they have their slide decks, you will be competing for their attention. Your initial read of the audience can also help you guide them directly to the parts of your material that matters most to them.

Aside from these five questions, it’s also important to consider the effect of your voice and your gestures – just as in a standing presentation. When seated, we still need to breathe fully from the diaphragm and speak with a strong voice. Make sure that those furthest from you can clearly hear you. Being seated allows for a more conversational and informal tone, but don’t become too relaxed, or you may lose your edge as an authority. Be sure both feet are firmly planted on the floor with your weight evenly distributed. Lean just slightly forward when you are speaking, so your audience sees your engagement with them. Some experts suggest relaxing this slightly when taking questions – sink back into the chair a bit so you appear approachable during the Q&A. Make eye contact with each person in the room, and sustain it for four to seven seconds per person, or longer if there are fewer people. Men and women face different obstacles non-verbally, as Amy Cuddy shares in her 2012 TED Talk. Knowing our personal predisposition in terms of space use, gestures, and nonverbal communication can be a great start to maximizing your non-verbal power.

Ultimately, it comes down to being thoughtful and strategic. When communicating from a seated position, success depends on your relationship with the audience and how well you can engage them within certain constraints. If you think about it, we all present much more often than we realize. We need to be conscious of how we can deliver our best, even when we’re sitting down.

The Most Productive People Know Who to Ignore

A coaching client of mine is managing partner at a very large law firm, and one of the issues we’ve been working on is how to cope more effectively with the intense demands on his time—clients who expect him to be available, firm partners and other employees who want him to address their concerns and resolve disputes, an inbox overflowing with messages from these same (and still other!) people, and an endless to-do list. Compounding this challenge, of course, is the importance of making time for loved ones and friends, exercise, and other personal needs.

When faced with potentially overwhelming demands on our time, we’re often advised to “Prioritize!” as if that’s some sort of spell that will magically solve the problem. But what I’ve learned in the process of helping people cope with and manage their workflow is that prioritizing accomplishes relatively little, in part because it’s so easy to do. Let’s define the term: Prioritizing is the process of ranking things—the people who want to take up our time, items on our to-do list, messages in our Inbox—in order of importance. While this involves the occasionally difficult judgment call, for the most part it’s a straightforward cognitive task. When looking at a meeting request, a to-do list, or an email we have an intuitive sense of how important it is, and we can readily compare these items and rank-order them.

Here’s the problem. After we prioritize, we act as though everything merits our time and attention, and we’ll get to the less-important items “later.” But later never really arrives. The list remains without end.

Our time and attention are finite resources, and once we reach a certain level of responsibility in our professional lives, we can never fulfill all the demands we face no matter how long and hard we work. The line of people who want to see us stretches out the door and into the street. Our to-do lists run to the floor. Our inboxes are never empty.

What trips up so many of us is imagining that we can keep lowering that threshold—by working harder, longer, “smarter” (whatever that really means) in the futile hope that eventually, someday, we’ll get to the bottom of that list.

The key is recognizing that prioritization is necessary but insufficient. The critical next step is triage. Medical staff in a crisis must decide who requires immediate assistance, who can wait, who doesn’t need help at all, and who’s past saving. Triage for the rest of us entails not just focusing on the items that are most important and deferring those that are less important until “later,” but actively ignoring the vast number of items whose importance falls below a certain threshold.

The first step is to reframe the issue. Viewing a full inbox, unfinished to-do lists, and a line of disappointed people at the door as a sign of our failure is profoundly unhelpful. This perspective may motivate us to work harder in the hopes of someday achieving victory, but this is futile. We will never win these battles, not in any meaningful sense, because at a certain point in our careers the potential demands facing us will always outstrip our capacity, no matter how much effort we dedicate to work. So the inbox, the list, the line at the door are in fact signs of success, evidence that people want our time and attention. And ultimate victory lies not in winning tactical battles but in winning the war: Not an empty inbox, but an inbox emptied of all truly important messages. Not a completed to-do list, but a list with all truly important items scratched off. Not the absence of a line at our door, but a line with no truly important people remaining in it.

The next step is to stop using the wrong tools. We expend vast amounts of energy on “time management” and “personal productivity,” and while these efforts can yield results at the tactical level, they’re futile when it comes to the strategic task of triage. Remember: this is not about making a list but deciding where the cut-off point is and sticking to it.

Finally, we need to address the emotional aspect of triage, because it’s not merely a cognitive process.

Actively ignoring things and saying no to people generates a range of emotions that exert a powerful influence on our choices and behavior. This is precisely what makes triage so difficult, and until we acknowledge its emotional dimension, our efforts to control our workflow through primarily intellectual interventions are unlikely to succeed.

This process may well be occurring right now. A moment ago when you read the phrase, “no truly important people,” above, you probably flinched a little and thought it was somewhat callous. I flinch when I read it, too, and I wrote it! But this understandable response is exactly why we devote time and attention to people who don’t truly merit the investment. There’s a fine line between effective triage and being an asshole, and many of us are so worried about crossing that line that we don’t even get close.

To triage effectively we need to enhance our ability to manage these concerns and other, related emotions (and “manage” does not mean “suppress”). As USC neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has written (and as everyone’s surely experienced first-hand), emotions can undermine effective decision-making by “creating an overriding bias against objective facts or even by interfering with support mechanisms of decision-making such as working memory.”

And this is exactly what happens to us when the active choice to ignore — the decision at the heart of triage — generates emotions that we fail to fully grasp.

When confronted by overwhelming demands on our time, we may feel anxious, scared, resentful, or even angry, but we’re often not sufficiently aware of or in touch with these emotions to make effective use of them. They flow through us below the level of active consciousness, inexorably guiding our behavior, but in many cases—and particularly when under stress—we fail to recognize their influence and miss opportunities to make the choices that will best meet our needs.

Improved emotion management is a complex undertaking, but there are a number of steps we can take that help:

Adjust our mental models to reflect emotions’ importance and the role they play in rational thought and decision-making. Our beliefs shape our experience.

Take better care of ourselves physically. Regular exercise and sufficient sleep demonstrably improve our ability to both perceive and regulate emotion.

Engage in some form of mindfulness routine. Meditation, journaling and other reflective practices enhance our ability to direct our thoughts, helping us sense emotion more acutely, and provide a new perspective on our experiences, helping us make sense of those emotions.

Expand our emotional vocabulary—literally. Having a wider range of words to describe what we’re feeling not only helps us communicate better with others, but also helps us to more accurately understand ourselves.

The ultimate goal is to expand our comfort with discomfort—to be able to acknowledge the difficult emotions generated by the need to triage so that we can face our endless to-do list, our overflowing Inbox, and the line of people clamoring for our attention and, kindly but firmly, say “No.”

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers