Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1382

August 13, 2014

The Irresistible Allure of Pre-crastination

There’s a fairly common maxim that “He who hesitates is lost.” It’s a curious proverb, not only because its origins are murky, but also because it might just be really bad advice for productivity. Recent research suggests that rushing to complete projects might actually harm our productivity, a phenomenon that’s been called “pre-crastination”—choosing a more difficult way to complete a task just to be able to mark the task complete.

This finding is the result of nine studies published together in Psychological Science by a team of Penn State University researchers led by David Rosenbaum. In each of the studies the researchers gave participants (Penn State undergraduate students) a simple choice: pick one of two buckets and carry it down an alleyway. While making the choice between the two buckets, participants were specifically told to pick whichever seemed easier for completing the task. The nine experiments varied the weight of the buckets’ contents (from zero to seven pounds) and where the buckets were placed relative to the participants’ starting point. (It’s worth noting that the researchers also varied the experiments to control for left- and right-handedness.) In most trials, one of the two buckets was significantly closer to the end point than the other. The researchers assumed that participants would prefer to pick up the bucket that was closer to the end point, but as the researchers were surprised to find, most chose the bucket closer to the starting point. In other words, in most cases, participants chose the task that took more physical effort, even though they were instructed to pick whichever task seemed easier. When researchers asked students in every variation of the study to explain their choice, the students’ most common response was that they “wanted to get the task done sooner.”

It might seem like a stretch to generalize bucket-carrying undergrads to the larger population, but the researchers’ explanation for what they observed resonates with an aspect of how many of us behave: we’re constantly trying to check off tasks to free up our working memory—the information we remember in the short-term. The researchers theorize that we desire the mental relief of getting a task done so much that we expend extra effort to get it. In an interview with APS, David Rosenbaum explains, “While our participants did care about physical effort, they also cared a lot about mental effort. They wanted to complete one of the subordinate tasks they had to do, picking up the bucket, in order to finish the entire task of getting the bucket to the drop-off site.” Rosenbaum and his colleagues theorize that participants were eager to remove the first step in the larger assignment from their working memory—so eager that they chose a harder series of tasks.

When it comes to structuring our work, many of us pre-crastinate in a lot of ways. How often have you rushed to complete a task ahead of time, only to find that you need to go back and fix common errors you should have known not to make? Have you ever spent the first few minutes of your workday constructing a plan for how to best use the next eight hours? When you look at your to-do list, do you tackle the easy stuff first, or do you focus on the most meaningful assignment on the list and dedicate your peak hours to completing that task? Have you ever spent a whole day responding to emails and simple tasks, only to find at five o’clock that you haven’t made any progress on the work that really brings value to you and the organization? While these tactics might feel productive in the short term and produce some small wins that keep us motivated, Rosenbaum and his team’s researchers suggest that rushing to completion too often only yields time wasted by having to go back to revise and refine the work done in haste. Instead of being eager to get things done quickly, perhaps we need to focus on getting things done more slowly but with better quality and less revisions down the road.

While it might be tempting to believe the old maxim that “He who hesitates is lost,” the research suggests that a little bit of “lost” time hesitating could turn into “found” productivity later on as projects get completed faster and better.

August 12, 2014

The Condensed September 2014 Issue

Amy Bernstein, editor of HBR, offers executive summaries of the major features. For more, see the September 2014 issue of HBR.

How to Get Ideological Opponents to Work with You

How do you encourage someone whose deeply held beliefs are at odds with yours to support and collaborate with you – or, at least, not obstruct you? Obviously, directly challenging their convictions will backfire. My research suggests some effective strategies.

Negotiations 101 teaches us to find something that is valuable to our opponents yet not costly for us to concede in order to encourage concessions from our opponent. In recent research published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, I describe how during ideological conflicts, proactively affirming the status of the people who don’t share your moral convictions may help you work together more effectively and to navigate through tense, complex situations.

In one of my experiments, for example, participants gave away roughly 40% more of their own tickets for a bonus lottery drawing to people who disagreed with them about the Affordable Care Act when their opponent affirmed their status than when he or she did not.

“Status affirmation,” as I call it, is more than being nice or simply saying, “I respectfully disagree.” It’s about satisfying people’s deep-seated, universal desire to be respected and – all things being equal – to generally increase in status over time. Imagine that two colleagues who work at a pharmaceutical company, Sarah and Kevin, have opposing views about Obamacare. While Sarah strongly believes that the legislation was an essential tool to fix our broken health care system, Kevin is adamant that it is an inappropriate government intrusion into the most personal aspects of people’s lives. Their ideological opposition spills over into many aspects of their working relationship and they frequently clash. As a result, Sarah expects Kevin to resist a promotion for which she has applied.

My research suggests that Sarah may be able to disarm Kevin by telling him how much she admired his tact and political savvy in a recent negotiation with a disgruntled client. By affirming that Kevin’s prestige and status in the company had increased as a result of how he handled that situation, Sarah is giving Kevin status, which he likely both desires (even if he never says so explicitly) and doesn’t expect to get from Sarah. Although Kevin probably won’t support Sarah when her promotion comes up for discussion, he is less likely stand in her way.

Here are some tips for how to avoid conflict and affirm your opponent’s status:

Do not try to change their opinion about the substance of your moral opposition. Unlike other conflicts or negotiations, your aim is not to persuade an opponent to agree with you. Instead, your goal is to engender a mutually respectful and collaborative relationship regardless of your ideological positions. In the previous example, Sarah did not try to change Kevin’s opinion about healthcare but to disassociate their moral positions from their working relationship.

Be sincere. You have to find something about the person that you really admire. For instance, acknowledge their commitment and passion, or recognize their skills in a completely different domain than the one over which you disagree, such as Sarah’s affirmation of Kevin’s tact with the unhappy client.

Be specific. Status affirmation is unexpected and may be met with skepticism. Had Sarah said she admires Kevin’s interactions with clients in general, it would have been less compelling and credible than praising what he did in that specific situation.

Be proactive by affirming status prior to engaging in negotiations or situations in which you need your opponents’ help. Had Sarah complimented Kevin’s handling of the client situation right before he went to the meeting to discuss her promotion, the tactic would have been less likely to succeed.

Although many people intuitively convey general respect when they are in conflicts and negotiations, status affirmation works best when your opponent receives something they really want – meeting an unspoken, underlying desire for status and respect – not just a hollow statement. Thus, proactively articulate sincere, specific respect without trying to persuade your opponents to change their moral convictions.

Internal Entrepreneurs Don’t Have to Be Lonely

Recent research confirms that entrepreneurs inside large, established organizations (which we’ll abbreviate to EIs) largely follow the same act-learn-build logic as new venture entrepreneurs, but with some significant differences. One of the biggest difficulties reported by EIs is that they have few colleagues (and sometimes no one) to talk to, explore ideas with, or gain emotional support from.

A new venture entrepreneur housed in Silicon Valley, for example, can walk down University Avenue in Palo Alto, accost and invite a virtual stranger for a latté in a nearby Starbucks, and spend an hour with a like-minded person in deep, productive, generative conversation. But EIs report feeling quite lonely. Even though they’re surrounded by people at work, they generally don’t have brainstorming partners or even like-minded individuals inside their organization, and tell us that for support they typically rely on popular books and conferences. These can certainly be helpful but are wholly incomplete—and terrible as a substitute for human relationships.

EIs can feel less lonely by forming support groups; finding partners; and enrolling more of their colleagues in their venture.

An EI support group will be likely be different from the colleagues who are specifically interested in your idea, although there may be some overlap. This sort of tribe, instead, consists of people who share an interest in entrepreneurial action within existing large organizations. An important aspect of this group is that its members care about you, as well. Such groups already exist in many metropolitan areas now (search online for “entrepreneur social networks” and your city, for example). Sometimes you can also find them in your organization — often, our in-house educational activities bring EIs together who then stay connected after a session together. While face-to-face meetings are likely best, you can find and join one or more online groups as well. If you’re an EI and you can’t find a tribe to join, extend real effort and time to form your own. The bottom line is that you should find a way. You need the support of people who “get” you.

In addition to a tribe it also helps to have a partner in advancing an inside venture. In a recent study of over 50 start-up ventures, more than 80 percent started with someone finding a partner before generating an idea. Just like in life, some of us make it through fine alone, but most of us search for a partner. We would speculate that your “inside” venture isn’t that different. It’s likely to be tough, and it’s simply easier when you have a committed partner— someone who complements your skills, to whom you can make commitments and who will hold you accountable, who can help you sort through your thinking, bring fresh ideas to the table, and more.

As you bring more people on board with your venture, you should also be continually engaged in two distinct but complementary modes of interaction with your peers and colleagues, whether they are part of your tribe or not: Selling and Enrollment. It’s easy to get these two confused (take a look at our previous blog How to Create Raving Fans). When you are selling, you are persuading; for example, convincing someone to buy or to do something. When something is sold, it is essentially a tangible transaction—an exchange of real things like resources or influence. Often incentives are involved, and there is generally some sort of quid pro quo.

By contrast, enrollment is a process of sharing and inspiring, with the aim of having the person “place their own name on the role.” It is an emotional and intangible transaction. Enrollment is based on fundamental conversations during which people are touched and excited. There are no deals to be made, and any incentives or payments will corrupt the process. You, personally, are vital for enrollment; this is less true for selling. People enroll in you as much, if not more than, your idea. Your vision, enthusiasm, and integrity are key.

Your success requires both sales and enrollment. You certainly can sell your idea on its economic merits alone, if you have them. But often at the conception of an idea, you don’t. So sell when you can, and enroll all the time. It is the combination of the two that will garner you the committed stakeholders and dedicated supporters you need.

Everyone has a potential part to play in your venture. It’s simply a matter of discovering, together, how they fit into your equation. You might find yourself getting calls from people who heard about your venture from someone else who heard about it from someone else; such propagation can be serendipitously beneficial. And it’s a lot more fun than going it alone.

Don Draper Is Replaceable; Joan Holloway Isn’t

In season three of Mad Men, Sterling Cooper’s rainmakers — including Don Draper and Roger Sterling — are planning to leave the ad agency and to take as many clients as possible with them. They’re in the firm’s Manhattan offices on a Sunday morning, plotting their exit, when the knowledge dawns: they don’t know where the client files are. They stare at each other, aghast. Fans everywhere screamed, “Joan! Get Joan!!” And indeed, the hyper-competent office manager, Joan Holloway, joins the men in the next scene, finds the files, and later recreates Sterling Cooper’s smooth-running routines in a new agency.

Sekou Bermiss, an assistant professor at the University of Texas, Austin, had the same response as the fan base, but from a different perspective: he was well into a research project examining which executives in ad agencies do the most damage when they leave (and add the most value when they don’t) based on data from New York City ad agencies from 1924 to 1996. A paper reporting on that research, co-authored by Johann Peter Murmann, is forthcoming in Strategic Management Journal. I spoke with him about his findings.

HBR: What’s the main takeaway of the research?

Bermiss: We separated the executives into two groups – internally facing people in charge of things like production, HR, and finance, and externally facing people like account executives and creative directors. Then we measured the effect of their departures on firm survival. Losing people from the first group – the internally facing executives – was significantly more damaging than losing people from the second group.

Why do those less-glamorous roles end up mattering more, do you think?

Those people know how the internal business operates – how the pieces fit together – and that turns out to be very valuable knowledge and, more important, fairly difficult to replace.

It’s not that creative people aren’t valuable! Of course they are. But there’s pretty good evidence that they’re more easily replaceable. It’s really hard to replace people who know the firm-specific routines and structures that make an agency competitive. It’s this specific knowledge, like how to manage the cash flow, the people, the production process … but it’s also knowing how the different functions fit together.

Did this finding surprise people?

It surprised people in the industry, yes, partly because all the media attention goes to the creative and account executives. When I discuss the findings, I get asked, “Did you control for this factor…for that factor?” But the truth is, we controlled for everything we could think of, and the data hold up.

Were academics surprised? Not as much. I could have argued it either way, in advance. As an empiricist, I was really curious to see what the data would tell us. We know from prior research that losing executives matters, and that different functional areas have different effects, but nobody had looked at the internal-vs-external question through a mobility lens before.

You didn’t have detailed data on profitability, so the outcome you looked at was firm failure. Is that a worry?

Right, I’d love to have had a complete set of data on firm performance, and I’m looking now at industries where it’s available. But for the larger firms that we can get more specific performance data on, the main effects still hold even after we’ve tortured the data. And remember, small firms do start up and die all the time – survival is a pretty good metric.

Should I be embarrassed that I immediately thought of Don Draper and Joan Holloway when I read about your research?

Not at all! I use clips from the show when I present the research. I’m a huge Mad Men fan.

Why You Shouldn’t Try to Win Over a Candidate During the Job Interview

The more a job interviewer tries to “sell” a candidate on working at the company, the less able he or she is to judge the candidate’s worthiness, according to a series of experiments by Jennifer Carson Marr of Georgia Institute of Technology and Dan M. Cable of London Business School. Making the job seem appealing becomes a distraction that gets in the way of accurate judgments. Firms would do better to separate the tasks of evaluating and winning over candidates and assign those roles to different people, the researchers say.

Why Western-Russian Sanctions Don’t Matter (Yet)

Concerns about political risk have heightened in the light of tit-for-tat sanctions between Russia and the West. Many observers seem genuinely shocked at the scale of the Russian reaction to three sets of Western sanctions imposed since the annexation of the Crimea earlier this year. But will these sanctions really bite? The details suggest not.

The first two rounds of Western sanctions followed the conventional post-9/11 wisdom, namely, that financial and individual sanctions work—so those close to the Russian president were targeted. Also, some firms benefiting directly from the annexation of Crimea were blacklisted. Whatever the optics, these steps aren’t likely to harm overall Russian living standards.

On the face of it, the third round of sanctions, announced by the US and EU in late July, are an entirely different matter. The emphasis shifted from targeting individuals to targeting key sectors of the Russian economy. Restrictions on the ability of Russian banks to sell financial instruments were imposed, as were bans on selling technology that would help Russia develop its vast energy reserves. An embargo on new arms sales and restrictions on so-called dual-use technologies were imposed.

Will these inflict costs on the Russian economy sufficient to induce better behavior on the part of the Kremlin? Assuming Western technology superiority in energy resource extraction isn’t lost, over the medium to longer term the third round of sanctions would likely trim Russian economic growth prospects. But will this register in today’s discussions at the Kremlin? More to the point: who can endure pain longer: the shareholders and board members of the Western energy companies that are harmed by these sanctions, or President Putin?

The implication is that the principal near-term impact of the West’s most recent sanctions must lie, if anywhere, in the financial sector. Even here the impact is likely to be smaller than advertised. Leaving aside the option of raising funds from the Middle East or developing Asia, as Peter Spiegel of The Financial Times has noted (pointing specifically to Article 5(b) of the text of the third phase of EU sanctions), subsidiaries of Russian banks based in the EU will still be able to raise funds in Europe.

Recall also that the sanctions apply to Russian financial instruments with maturities over 90 days. But, as Fitch has shown recently, many Russian banks are unlikely to be hurt much as a large fraction of their external liabilities are very short-term, held by a subsidiary in the EU, or because the bank has such strong ties to the Kremlin that it is likely to be bailed out.

All in all, the bark of recent Western sanctions is worse than their bite.

And the same can be said of Russia’s “shocking” counter-sanctions. Russia has targeted agricultural products from Australia, Canada, the European Union, Norway, and the United States. A number of Western commentators reckon that these sanctions will raise food prices for Russians, pushing up core inflation, and so inflict an injury domestically. This textbook logic may overlook some pertinent facts. Russia can source banned food stuffs from alternative suppliers—to many, Turkish white cheese is just as good as Greek feta. Moreover, should food prices start rising then Russia could cut its agricultural import tariffs—which the latest WTO data suggest are around 13% on average—or bolster subsidies to the agricultural sector. Russia is surely comfortable doing the latter. The Global Trade Alert team, which I coordinate, has documented over 60 subsidy schemes and bailouts in the Russian agricultural sector since Q4 2008.

The impact of Russian sanctions on Western agricultural exporters is likely to be limited as well. Much has already been made in newspaper accounts of the successful reorientation of Dutch and German pork exports earlier this year in response to an (unrelated) Russian import ban. Of course with perishable food there’s a risk of export disruption. But then it shouldn’t be forgotten that, when it comes to farmers, Europe has remarkably deep pockets.

As the dust settles after Russia’s retaliation, a dispassionate look at the form of each side’s sanctions suggests that nothing terribly consequential has occurred. Neither side has extracted a pound of flesh nor shown any willingness to sacrifice one. Maybe each party decided independently that this was in their interests. The West signals that further escalation is still possible, without wrecking trade relations. The Russians have struck back as they feel they must to appease nationalist feeling.

The biggest risk of the moment, then, is of miscalculation. The hardliners in both camps are on constant lookout for any sign of weakness that can be seized upon; if they see that now, their next steps could do real harm. And thus a moment that still holds the potential for constructive resolution could be lost.

August 11, 2014

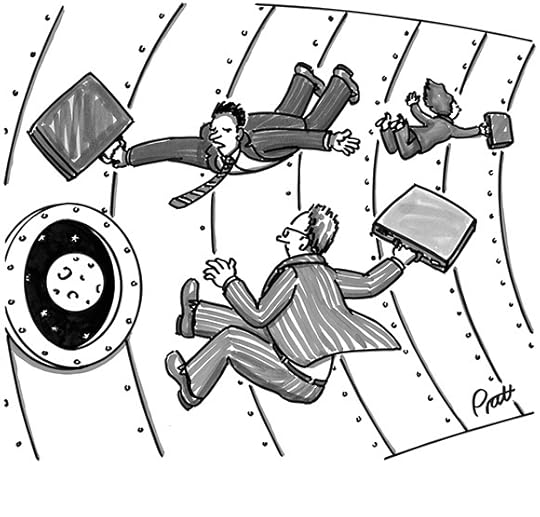

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the September 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the September issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

Harley Schwadron

“Now that you’ve come in to some money, perhaps you’d like to take a look at a few of our investment services.”

Susan Camilleri Konar

“Sorry to see you go, Doug. You leave us with some big shoes to outsource.”

John Caldwell

“I hate when our grandparent company visits.”

Roy Delgado

And congratulations to our September caption contest winner, Andrew Card of Medford, Oregon. Here’s his winning caption:

“Apparently ‘adventure capitalists’ wasn’t a typo.”

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by August 26.

Cartoonist: John Klossner

Can Lending Technology Revive America’s Small Businesses?

Ever since the early days of the recovery, it’s been a common refrain that Wall Street was able to emerge from the Great Recession while Main Street was left behind. It’s more than just rhetoric.

Main Street has in fact been slower to recover from the recession, and much-needed capital on which small businesses rely has been in shorter supply. Factors ranging from weak demand to bank consolidation have combined to hobble many small businesses – and if these factors aren’t addressed, they could continue to impede U.S. job growth and economic security.

In short, the health of American small businesses depends significantly on credit. And as we describe in a recent HBS Working Paper, gaps remain in traditional bank credit supply.

It’s worth remembering why small business matters in the first place: small firms employ half of the private sector workforce—about 120 million people. Since 1995, small employers have created about two out of every three net new jobs—65%of total net job creation. Small businesses are also instrumental to our innovation economy; small firms produce 13 times more patents per employee than larger firms and employ more than 40% of high technology workers in America.

Moreover, small firms are core to America’s middle class and part of the fabric of Main Streets across our country. Even though we cannot say for certain the extent to which new businesses generate middle class jobs, we do know that company founders come from the middle class themselves. According to a Kauffman Foundation study, 72% of entrepreneurs surveyed come from self-described middle class backgrounds, and another 22% reported being from “upper lower class” backgrounds.

But the strength of small business is dependent on the availability of bank loans, and the evidence suggests this critical funding may be drying up.

The majority of small businesses rely on such loans, and in the fall of 2013 alone, 37% of small businesses applied for credit. (Another 20% might have, but were discouraged from doing so because they believed they wouldn’t get the loan, or because the process was too arduous.)

Yet small business lending has declined steadily since the recession.

In contrast, loans to larger firms have risen every year since hitting bottom in 2011, and are now up about 4% since that low point.

The reasons for this decrease in small business lending are many, and in our research we discovered plenty of disagreement over the causes. Bankers, for their part, allege that they are anxious to do more small businesses loans but are finding a shortage of credit-worthy candidates.

The most useful way to sort through the various causes is to distinguish between the cyclical and the structural. Small business sales were hit hard during the crisis and may still be soft, undermining firms’ demand for loan capital. Financial crises hit sources of collateral like real estate particularly hard, and this has negatively impacted smaller firms’ credit scores. Banks remain relatively risk-averse amid the tepid recovery. And increased banking regulation may be forcing banks to be more risk adverse and to conserve capital that might otherwise have gone toward small business loans.

These are all cyclical factors that we might expect to improve with the economy over time. In contrast, several longer-term structural factors are contributing to the dearth of small business lending.

In comparison to larger firms, small businesses are less well equipped to efficiently navigate the loan process – in economic parlance, their search costs are higher. And for banks, the transaction costs of a loan tend to be the same regardless of the loan’s size, such that larger loans are a more efficient use of time and resources.

Finally, the number of community banks – the most likely institutions to lend to small firms – appears to be in decline. Most of the banks shuttered during the recession were community banks, and new ones have not materialized to take their place.

Taken together, these trends are cause for concern, as they may threaten the viability of U.S. small businesses. But there is also reason for optimism.

Since the onset of the financial crisis, and particularly during the economic recovery, there has been significant growth in innovative alternative sources of loan capital to small businesses, driven by technology. Emerging online players like Funding Circle, LendingClub, and Fundera are stepping into the void left by the consolidation and retrenchment of the banks, and pushing innovation within the banking sector just as Amazon changed retail and Square changed the small business payments business.

The growth of these alternative lenders is driven by more than just a greater appetite for risk. Alternative lenders are innovating in small business lending, particularly in terms of simplicity and convenience of the application process, speed of delivery of capital, and a greater focus on customer service.

For example, all of the biggest players emerging in the alternative lending space offer online and mobile applications, many of which can be completed in under 30 minutes. These are not just inquiries; these are actual loan applications, which compares to the average of about 25 hours that small businesses spend on filling out paperwork at an average of three conventional banks before securing some form of credit. Upon filling out an online application, borrowers can be approved in hours and have the money in their account in just days, whereas in the conventional banking model small business owners may not have their loans approved for several weeks. Some of these services are also relying on broader sources of data, combined with new methods of predictive modeling, to better assess creditworthiness.

These lenders vary along several dimensions – you can read more about them in our full report – but together they offer hope that the small business credit market may be being reinvented. These entrants may also push traditional lenders such as large banks and credit card companies to adopt new innovations, and use their large stores of borrower data and existing relationships with small businesses as a competitive advantage.

These developments, while promising, are not without risks. Although the online small business lending market is in its infancy, there is already disagreement over the appropriate level of regulation. On one side, many view the new entrants as disruptors of an old and inefficient marketplace, and caution against regulating too early or aggressively for fear of cutting off innovation that could provide valuable products to small businesses and fill market gaps.

But, on the other side, there is already concern that, if left unchecked, small business lending could become the next subprime lending crisis, as was recently pointed out by Bloomberg BusinessWeek in an article that has garnered significant attention in the industry. Traditional players, including community banks, are weighing into the debate as well, fearing that stronger regulatory oversight in the wake of the recession is leaving them less competitive relative to new entrants that have to date operated in largely unregulated markets.

The diversity of models in alternative lending cautions against a one-size-fits-all approach to policy; different approaches must be treated differently. Still, the need for transparency and oversight is clear.

The policy challenge is to ensure that these new marketplaces have sufficient oversight to prevent abuse, but not so much oversight that the innovation is dampened or delayed.

In the wake of the worst recession since the Great Depression, the state of American small businesses is precarious. Neither sales nor employment have fully recovered, and credit seems harder to come by. The potential of new technology to fill the gaps in small business lending is high. In fact, we may be seeing a technology disruption in small business lending along the lines of what we’ve seen over the last few decades in industries like travel and media. If it’s successful, small businesses will have more opportunity to what they do best—grow the American economy and create jobs.

When (and Why) to Pay for Tweets

If you’re on social media, you’ve seen them: ads dressed up to look (almost) exactly like normal tweets, Facebook posts, and LinkedIn updates from your friends and followers. They’re called native social ads, and while user opinions vary from indifference to annoyance, the results would seem to speak for themselves.

Facebook native ads that appear in users’ news feeds are clicked on 49 times more often than traditional banner ads in the right sidebar, according to AdRoll. Meanwhile, Promoted Tweets have shown engagement rates of 1% to 3%. Normal banner ads are clicked on just 0.2% of the time.

Advertisers are clearly pleased: Overall spending on native social ads will nearly triple from $1.6 billion in 2012 to $4.6 billion in 2017, according to an analysis by BIA/Kelsey. Granted, this is a small chunk of the $121 billion to be spent on Internet advertising this year. But for businesses seeking to market through social media channels — in real-time and with detailed reporting — native social ads represent a uniquely promising new frontier.

My company was an early adopter, purchasing our first social ads in 2012. Now we spend a significant portion of our marketing budget on paid social ads, drafting and placing hundreds every month in multiple languages. The returns continue to exceed expectations: Social ads now drive a major portion of our enterprise-level customer leads and do so at a lower cost than any other paid ad channel. Here’s what we’ve learned about how to use paid social effectively:

1) Use free social media to beta-test your paid social ads.

If your company is on social media, you’re likely already sending out multiple Tweets, Facebook Posts, and LinkedIn Updates every day. Some of these messages will resonate with followers; others won’t. Using free analytical tools (I’m partial to Hootsuite, but there are many out there), it’s easy to track which ones are being clicked, shared, and commented on.

It’s precisely these high-performing messages that make great candidates for native social ads. You already know they “work,” taking the guesswork out of the creative process. All you’re doing is taking a tried and true message and paying to put it in front of a newer, larger audience.

2) Take advantage of targeting features.

One of the major rubs with traditional ads is inefficiency. (Every time a die-hard Prius owner sees an ad for a gas-guzzling SUV, for example, it represents a major waste of resources.) Social ads minimize this type of spillage.

On LinkedIn, sponsored updates can be targeted to particular regions (countries, cities, etc.) and industries, as well as to specific job titles and even particular companies. Twitter allows advertisers to drill down based on region, gender, device, and literally hundreds of different interest categories. Messages can even be aimed at specific brands and their respective followers, enabling businesses to go directly after the competition and its client base.

Meanwhile, Facebook’s sponsored posts can be blasted out to a nearly endless list of interest groups. (If you can think of a demographic — say, Game of Thrones fans — Facebook can target their news feeds.) Facebook can even go after “lookalike audiences,” i.e. users who have already expressed interest in products similar to yours. And on all these networks, you’re not just limited to existing friends and followers but can reach any groups or individuals who fit a desired profile.

3) Rotate ads frequently.

With TV commercials and other traditional “interruption ads,” repetition is the name of the game. But promoted tweets and sponsored posts appear right in users’ news feeds. Not only are engagement rates bound to plummet if you hammer users on their home turf with repetitive messaging, but you may end up losing more business than you gain.

The remedy here is fresh, ever-changing ad content. Because tweets and posts are generally short and sweet, this is hardly a heavy burden. At the same time, social ads can be reused by targeting them to multiple demographics. Rotating the same message through a series of different, highly targeted groups, in fact, is one of the easiest ways to extend the life and utility of native social ads.

4) Use small samples to A/B test your social ads.

One of the great virtues of native social ads is instant feedback. Minutes after sending out a promoted tweet or sponsored post, for example, it’s possible to gauge its effectiveness. Detailed analytics reports and charts show who’s clicking and how often.

Before doubling down on a single social ad, we’ve found it effective to send out several “test” ads to small audiences and wait to see the results. For minimal spend, we get a clear, data-driven picture of which ad performs best. Then we’ll back the winning message with additional spending to ensure it reaches the largest audience.

5) Understand how ads are sold.

Different networks sell ads in different ways. On Twitter, companies pay on an engagement basis. Every time users take an “action” — click, retweet, favorite, etc. — a fee is assessed. Meanwhile, Facebook and LinkedIn offer the option of paying per impression, where companies are charged whenever their ad shows up in users’ streams (regardless of whether or not it’s clicked on).

Though the difference may seem academic, it’s critical to bear these two pricing models in mind and to design tweets and posts accordingly. For example, since we pay Twitter each time users click on our ads, it’s important that people be genuinely interested in the content waiting on the other side. This requires drafting Tweets that are clear and straightforward — in essence, the opposite of “link bait.” The goal here is to drive genuine prospects to our site, not merely to attract as many eyeballs as possible.

6) Design your ads with smartphones in mind.

Social media is consumed overwhelmingly on mobile devices. Twitter users spend 86% of their time on the service on mobile. Facebook users aren’t far behind at 68%. This means messages have to be optimized for viewing on small mobile screens. For promoted tweets, this is hardly a challenge, given the 140-character limit. For Facebook’s sponsored posts, this requires keeping messages short and sweet and, ideally, image-based.

But the fact that native social ads are viewed on a device people carry around with them at all times also opens up unique marketing possibilities. Twitter recently unveiled a feature enabling paid Tweets to be targeted by zip code. Users walk into a neighborhood, for instance, and suddenly promoted tweets for the local pub, dry cleaner, or McDonald’s might pop up in their Twitter stream. This kind of “geofencing” technology, which Facebook has had since 2011, enables businesses to court the kind of walk-in customers most likely to act on limited-time deals and in-store specials.

Digital advertising is a notoriously fickle field, and trends come and go. Banner ads boasted click-through rates of up to 5% in the late ‘90s before viewers learned to simply tune them out. There’s good reason to believe, however, that native social ads are poised for growth and here for the long haul. (In fact, Instagram and Pinterest — two fast-rising visual social networks — have just unveiled their own versions.) Native social ads are cheaper to produce than traditional ads and reach their target with impressive efficiency. Plus, at their best, they’re creative, entertaining and even useful — a novel concept in advertising and one whose time has come.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers