Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1383

August 11, 2014

You’re More Likely to Pursue Your Goals After a Birthday or the First of the Month

People are more likely to exercise after a birthday or the start of a week, month, year, or semester (7%, 33%, 14%, 11%, and 47%, respectively, relative to baseline), suggesting that temporal landmarks make it easier to engage in aspirational behavior, say Hengchen Dai, Katherine L. Milkman, and Jason Riis of The Wharton School. In a series of studies, the researchers found evidence that these landmarks create new “mental accounting periods” that psychologically distance the present self from its past imperfections.

What Business Schools Don’t Get About MOOCs

There’s trouble in business-education paradise.

Recent news stories have described significant dissension at Harvard Business School about MOOCs (massive open online courses). For the uninitiated, MOOCs are courses that are taught over the internet, and which are usually open to all comers. In the spirit of full disclosure, I recently taught a MOOC for IESE Business School on the Coursera platform. I’m also a graduate of Harvard Business School and a former faculty member there. So I am hardly a neutral party.

But much of what has been written thus far about MOOCs – are they good or bad? Will they put universities out of business? – misses the point. The future education will be the recombination of new and old, not a battle between them.

This misguided debate over MOOCs can be seen in the contrasting approaches of HBS and Wharton. HBS has decided not to embrace one of the existing MOOC platforms, but rather, to invest heavily in a proprietary platform. Michael Porter, the strategy expert, believes that the HBS approach is the right one. Clay Christensen, the innovation expert, advocates instead the approach taken by Wharton, which has made MOOCs out of all its core courses.

It would be awkward to pick sides between two old friends about the strategy of a school where I taught for more than twenty years. But I don’t have to. Both the HBS and Wharton approaches seem not so much wrong as seriously incomplete.

HBS is using its online platform to target a set of students—pre-MBAs—whom it doesn’t currently serve. And Wharton-style models, according to the school’s research, “seem to attract students for whom traditional business school offerings are out of reach.” In other words, both schools treat MOOCs as complements to their existing offerings, rather than as substitutes—complements that are disconnected from what goes on in their traditional classrooms.

This brings to mind the dilemma faced by bookseller Barnes & Noble (B&N) back in the 1990s, when Amazon started selling books online. To its credit, B&N quickly set up an online interface to complement its store-based services. But—a key point!—it kept the online venture separate, organizationally and operationally. The company simply straddled the two channels, without creating any operating linkages across them.

B&N would have been far better off pursuing a different kind of strategy—recombining, rather than straddling. This would have involved combining its unmatched store network with elements of online book retailing. The company finally began to move in this direction in 2000, but too late to thwart Amazon.

The B&N precedent raises the question of whether business schools—even elite ones—can afford to maintain a business-as-usual approach to their traditional core operations. They say “yes”; I say “no.”

What are their arguments?

Point: In terms of learning outcomes, MOOCs are inferior to traditional in-class instruction.

Counterpoint: Probably. But a focus on learning outcomes is too narrow for at least three reasons. First, it undervalues other benefits to students, such as flexibility in terms of timing. Second, factoring in cost makes online technology much more competitive. And finally, focusing on current relative positions discounts the importance of technological change—which, over time, will make online models more competitive.

Point: Cost pressures don’t matter at leading business schools.

Counterpoint: The argument here is that the leading business schools can raise prices as much as they want. But the average discount on full-time MBA tuition at high-ranking private U.S. business schools is 52%—and it’s 56% at Harvard Business School.

Point: Irrespective of the economic pressures, institutions with massive endowments don’t have to change.

Counterpoint: Maybe. But are these institutions that stick to traditionalism doing the best they can for their students? If not, that’s an abdication of their roles as stewards (of those endowments) and as professional educators. The question should be, Can we do better? At IESE, for example, we are experimenting with splicing material developed for my MOOC into the traditional course on globalization that I also offer.

Point: The traditional learning model—at HBS, in particular—is about social learning, and therefore invulnerable to substitution threats.

Counterpoint: This might have been true of the HBS approach in years past, when you could leave the classroom after 80 minutes of discussion without a clear idea of what the discussion leader actually thought about the topic at hand—an approach intended to foster independent thinking. Today, it’s more or less routine for faculty—especially the younger ones—to present a list of “takeaways” at the end of class. This is exactly the kind of material that can, and should, be delivered online.

The advantages of MOOCs and, more broadly, online technology as a delivery channel, are real. Rather than simply tacking on complementary online offerings, business schools need to experiment with their core. They must create strong linkages between new digital initiatives and the rest of the institution through mechanisms such as cross-staffing, multiple points of contact, and unification of reporting and decision structures. And these mechanisms need to be invented now, before the way forward is clear.

Our mindset needs to shift from seeing in-class interactions as intrinsically superior to focusing the two approaches on their respective comparative advantages. This won’t be easy. Yeats wrote that education is not about filling a bucket, but lighting a fire. But the way we run the educational sector is about filling buckets—or, more precisely, a specific number of classroom sessions of a particular duration. Treating classroom time as a scarce resource, to be valued highly, and used carefully, is very different from treating it as a bucket to be filled.

Will this mindset shift actually happen? Clay Christensen once used to think so: “If anyone can beat the odds against being disrupted, it is our remarkably capable and committed colleagues in higher education.”

Another celebrated academic named Clay— my NYU colleague, Clay Shirky—takes a very different view: “We have several advantages over the recording industry, of course. We are decentralized and mostly non-profit. We employ lots of smart people. We have previous examples to learn from, and our core competence is learning from the past. And armed with these advantages, we’re probably going to screw this up as badly as the music people did.”

I hope Christensen is right, but I fear that Shirky may be.

August 8, 2014

Managing Ebola Will Take Powerful Communication

Whether the world’s scariest outbreak of Ebola can be managed may come down to communications. Can governments, NGOs, and doctors communicate with very different audiences – with accuracy, agility, and ingenuity? Can they be convincing?

After years of civil war, many people in the affected countries don’t trust their governments or the foreigners in bio-hazard suits who seem to bring the virus with them. They don’t understand how the virus is being spread. Local custom is to bathe the bodies of the dead – but in doing so, the living catch the virus. Traditional sources of food – wild animals – also carry the virus.

Think of the tough barriers that messaging must get through to stop this outbreak: don’t eat the animals you have always eaten in the past; don’t touch your loved ones if they are ill; don’t follow age-old or religious customs in washing a dead relative’s body; don’t use the shaman’s cure you have always trusted in the past; and yes, many will survive if they get proper treatment (though there is no cure). Think of how you might try to get the message out to a rural population with little electricity (and therefore limited access to TV and radio, let alone the internet) and low literacy rates.

To find some ideas for the terrible situation unfolding in West Africa now, it may be useful to look to past efforts in fighting HIV, leprosy, and diarrhea (a major killer of children under the age of 5 in emerging markets). Those campaigns educated and informed through the ancient arts of personal and personalized local folk media.

Nearly 800,000 children under the age of five die every year due to diarrhea (according to WHO). It is the second biggest killer of kids in the world. Many of those deaths could be prevented if the caregivers would simply wash their hands with soap and water. However, in poor areas, soap is considered too precious to use all the time. Many organizations, communications agencies, and even companies have made a positive impact, however. They create street theater, puppet shows, skits and songs that do not depend on reading leaflets or having access to TV or internet. They craft analogies to teach about concepts such as germs or viruses, since assuming they already understand basic biology is a fatal assumption.

For instance, Ogilvy PR created an award-winning campaign that saved many lives in Indonesia called “Fantastic Mom.” The insight was moms were the reason children were getting diarrhea — because they did not wash their hands at crucial times. Local communicators created puppet shows and songs that made heroes of the mothers, brought the idea to life – and saved lives.

Ogilvy also worked with Unilever, maker of Lifebuoy soap, to turn roti (Indian flat bread) into a messaging vehicle. At an enormous festival, the roti were stamped with a hot branding iron that bore a message to wash your hands before eating. Unilever has also run a sustained initiative to teach proper hand washing that has reached 130 million people.

In Uganda, Medical Research Council AIDS Directed Program also found positive results using theater as the educational vehicle. In rural Ghana, folk media (puppetry, songs, proverbs, theater, and storytelling) has combatted HIV/AIDS, according to CARE International researchers. In India, the World Bank Health, Nutrition and Population department has seen a positive impact from the use of folk media in combatting leprosy in rural and illiterate populations. Theater works in rich, educated countries too. Kaiser Permanente has reached more than 15 million in the U.S. through its Educational Theater Program. No matter where you are, facts alone won’t change minds, and fear is a powerful distorter of any message.

Here is why drama and storytelling work. Lawrence Kincaid is health communications expert and scientist at the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. His research (“Drama, Emotion, and Cultural Convergence”) delves into drama theory — basically how audiences empathize with characters and vicariously live their conflicts through them, even riding with them through their change of mind. His work has been used to help prevent risky behavior leading to HIV transmission through creation of TV and stage dramas. Researchers such as Raymond Mar, Melanie Green, and Geoff Kaufman have also found that fiction — far more than expository or non-fiction evidence — has the power to change minds and thus behavior. Mar, assistant professor of psychology at York University says: “The more that people are transported into the world of the narrative, the more they feel immersed in the story, the more likely they are to change their beliefs to be more consistent with those expressed in the world of the narrative.”

“We’re stepping into the lives of these characters,” says Green. “The empathy we create goes out beyond just those few moments when we were thinking about the story.”

Kaufman’s work using drama to change high-risk behavior related to HIV transmission found: “People who report higher levels of experience-taking are subsequently more likely to adjust their behavior to align with the character’s.”

But creating such stories takes time – more time than crafting a Facebook campaign or A/B testing different messages on Twitter. And it also takes time to get the message out into the community. As an expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, Laurie Garrett, who is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author (“The Coming Plague”) answered my question in a special CFR session August 5 that a “Western style of doing a media campaign … is not what is needed on the ground. What’s needed is really direct communication that begins by identifying key community leaders, village-by-village, neighborhood-by-neighborhood. Who are the influence-makers? Who are the individuals that everyone else follows and obeys for one reason or another, whether they are religious, political, gangsters, whoever they are, and winning them over step by tedious step.” Garrett went on to caution that beyond tedium, “it’s dangerous work.” “They’ll throw rocks at you … and you don’t know who’s infected.”

To manage what the WHO has declared an international health emergency will of course take clear, accurate, consistent communications updated in real time and using all the always-on, digital, and social media tools at hand for 21st-century communicators. But stopping Ebola at ground zero will require the ancient arts of story and drama that predate Pinterest, Facebook, and Twitter by thousands of years.

A CEO Stepped Down This Week to Spend More Time With His Children. Yes, That CEO Is a Man

Max Schireson, the chief executive of database company MongoDB, was working the typical “crazy full-time” hours of a CEO. He was on pace to log 300,000 air miles this year — not unusual for a top executive who commutes cross-country from his home to his job. But then he decided he didn’t want to work crazy full-time and fly all over the world if it meant missing important moments in the lives of his three adolescent children. So he announced in a blog post that he would be stepping down, handing the reins to someone else, and remaining vice chairman so that he could work normal full-time.

“I decided the only way to balance was by stepping back from my job,” he writes. The company “deserves a leader who can be ‘all-in,’” and that’s not him. So he’s literally choosing to spend more time with his family, a phrase that has become a punch line in corporate scandals but in this case will resonate with every high-powered mom or dad who has wished for more downtime with the kids before their very short childhoods vanish into adulthood. —Andy O’Connell

How Scared Should We Be?AI, Robotics, and the Future of JobsPew Research

Here's the gist of this report based on a survey of 2,000 technology experts: 48% say that by 2025, robots and other forms of automation will have displaced more jobs than they created. The other half say that while robots may replace many tasks done by humans today, "human ingenuity will create new jobs, industries, and ways to make a living, just as it has been doing since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution." If this all seems a little too black-and-white, don't fret. The report contains reams of nuanced thoughts from all these smart people about the economy, how things may or may not change for workers, and how we think about jobs. And if you need a short version, here's Claire Cain Miller's roundup in The New York Times, which categorizes opinions ranging from the most utopian to the most frightening.

The Pen in the Invisible HandThe Economics of Jane AustenThe Atlantic

Jane Austen was as intrigued by economics as she was by love and morals. Her characters are always searching for financial support, and the minutiae of their quests tell us a lot about seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century English society. The Atlantic’s Shannon Chamberlain points out that Adam Smith, the inventor of the study of economics, exerted a deep influence on liberal English thought during Austen’s lifetime, and his analysis of how people interact to further their self-interest echoes throughout Austen’s stories. People’s delusion (yes, he considered it a delusion) that it’s good to be rich “keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind,” wrote Smith, but the sentiment is novelistic and worthy of Austen. —Andy O’Connell

Some Slack The Most Fascinating Profile You’ll Ever Read About a Guy and His Boring Startup Wired

Once you get past the slight headline hyperbole (though I appreciate the effort), Mat Honan's profile of Stewart Butterfield, Flickr creator and epic memo writer, is, indeed, a delightful read. Aside from sketching Butterfield's biography as the son of a U.S. draft dodger whose onetime goal was to create a video game that would never, ever end, Honan investigates Butterfield's newest start-up, Slack, which aims to become the next Microsoft — but one "you want to use." Currently implemented by Gawker Media, Expedia, and Crossfit, to name a few companies, Slack aims "to become the hub at the center of all your other business software" — and to do it by word-of-mouth, so that eventually your IT department has to start using it. The model isn’t perfect: It has an expensive subscription rate, and places like Gawker have been using it free for months (the downside of Slack's marketing approach). So I propose this headline change: "The Most Well-Written Profile (Honan Can Write, Guys) You'll Ever Read About a Guy and His Startup that Could Change Everything About the Way We Work." Yawn.

Happy Reading This Is the Unauthorized Letter Passed to Elite MBAs For DecadesBusinessweek

Back in the late 1980s, Stanford Graduate School of Business student Shirzad Bozorgchami (who now goes by Shirzad Chamine), wrote a letter to fellow students as something of "a manual for getting the most out of business school without being too much of a nerd about it." Since then, first-year students at Stanford, Wharton, and other schools have received a copy of the letter in their mailboxes, an unofficial reminder from more senior students about keeping the craziness and pressure of school in perspective.

The letter, offered in Businessweek, is full of specific recommendations about study methods and stress. But just as interesting is the story behind why Chamine wrote it. After a classroom exercise involving a critique of students' interpersonal skills — during which Chamine was found by many to be too judgmental — he wrote the piece as a thought experiment about "how not to turn self-doubt into hostility toward others." The rest is B-school history.

BONUS BITSGet Jacked (or at Least Go for a Walk)

The Working Parent's Complete Guide to Working Out (Quartz)

How the Other Half Lifts: What Your Workout Says About Your Social Class (Pacific Standard)

Science Says You Should Leave Work at 2 p.m. and Go for a Walk (Mother Jones)

Make Getting Feedback Less Stressful

Much of my work as an executive coach and an instructor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business involves helping people improve their abilities to deliver feedback more effectively. It’s a critical skill, particularly for both leaders in flat organizations where giving orders is generally counter-productive and for anyone who needs to manage up or across by influencing their bosses or peers. And it’s a topic on which I’ve written extensively, not only in posts on my site and at HBR.org, but also in the HBR Guide to Coaching Your Employees.

But a recent exchange with my colleague and former Stanford student Anamaria Nino-Murcia made me realize that I’ve been neglecting the other half of this equation: How to receive feedback more effectively.

First, we need to recognize that receiving feedback is inherently a stressful experience. As Sheila Heen and Douglas Stone wrote in “Find the Coaching in Criticism” in the January-February issue of HBR, “Even when you know that [feedback is] essential to your development and you trust that the person delivering it wants you to succeed, it can activate psychological triggers. You might feel misjudged, ill-used, and sometimes threatened to your very core.” And this is true even in feedback-friendly organizations, and it’s even worse in environments where feedback is infrequent and surprising.

As a species, we have developed a “threat response,” a cascade of physiological, emotional, and cognitive events that occur when we perceive a conflict. We typically refer to this set of reactions as a fight, flight, or freeze response. Recent neuroscience research has shown that our brains and bodies can respond to certain interpersonal situations the same way we react to literal threats to our physical safety. Psychologists refer to these experiences as “social threats.”

Executive coach David Rock conducted an extensive study of the relevant research and developed the SCARF model [PDF] to help identify interpersonal dynamics that are likely to trigger a social threat. What’s striking is how many of these dynamics are present in a typical feedback conversation:

Status: Feedback often comes from leaders and managers who occupy a position of higher status in the relationship. And when feedback comes from a peer or subordinate, you may interpret their behaviors as the temporary assumption of a higher status role.

Certainty: You may know little about the content of the feedback, particularly in an organization or a relationship where feedback is rarely offered. Even if you have a sense of what the conversation will be about, you can’t be certain about its specific content.

Autonomy: You may feel required to participate in the conversation, especially if a manager has initiated it. And the increasing prevalence of a “feedback-rich culture” (which I’ve helped to promote) may make you feel obligated to participate in a feedback conversation anytime anyone wants to have one. This makes your participation feel less like a choice.

Relatedness: As with status, when someone is providing feedback you may perceive them as temporarily assuming a more distant role, resulting in an diminished sense of personal connection or closeness.

Fairness: You may well view feedback as unfair, particularly if the feedback giver makes inaccurate assumptions about the motives behind your behavior (as they often do.)

These dynamics can trigger a social threat in every one of us. When we encounter people of higher status, when we experience uncertainty, when we feel less autonomy or freedom of choice, when we feel less connected to those around us, and when we believe that something is unfair we are more likely to experience a social threat. It’s no wonder that feedback can be so stressful!

With this context in mind, here are the keys to receiving feedback more effectively.

Reframe the experience: In the moment, you can use Rock’s SCARF model to better understand what’s happening, and employ your conscious awareness of those dynamics to diminish your sense of social threat. This is a long-established psychological technique derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy known as cognitive reappraisal or, more simply, reframing. Psychologists such as James Gross and Rebecca Ray of Stanford and Kevin Ochsner of Columbia have shown that reframing can reduce stress levels and increase our abilities to manage negative emotions.

In the context of a feedback conversation, you should remind yourself of the following:

Your perception that feedback is threatening is rooted in clearly understood neurological and psychological dynamics. The feeling of being threatened doesn’t automatically imply that you are facing a literal threat.

The person providing you with feedback isn’t necessarily assuming a position of higher status or lording their status over you. In most cases their intentions are simply to help you improve—even if they’re doing so ineffectively.

Even if you feel obligated to participate in the conversation, you are making the choice to respond to that pressure, and you do have some agency.

If you feel as if the feedback is unfair, keep in mind that you may be misunderstanding the feedback giver’s motives. And they may have made some wrong assumptions about you as well. If this is the case, try stating your true intentions and point out how they differ from what the feedback giver has assumed.

Note that reframing has its limits, and your capacity for feedback is finite. At certain points you’ll be unable to fully comprehend the other person’s comments, or you’ll become distracted by your own inner monologue, or you’ll simply feel overwhelmed or flooded with various emotions. These are signs that you’ve absorbed all the feedback that you can at the moment. When this happens you should pause the conversation so that you can make sense of what you’ve heard so far, and agree to continue only after you’ve had an opportunity to reflect.

Build the relationship: Over time, you can develop closer relationships and build trust with the people who are likely to give you feedback. This will help you feel more comfortable.

The work of John Gottman, a social psychologist at the University of Washington and a leading expert on relationships, suggests that the following steps can help:

Share more personal information about yourself so you and the feedback giver grow more familiar with each other. You could do this over a meal, of course, but that’s not always possible. At the start of the feedback conversation, just take a few seconds to disclose how you’re feeling before jumping into the business at hand.

Express more appreciation, even for small gestures. We tend to minimize signs of appreciation in our working relationships because we assume that the other person knows how we feel, or we fear that our appreciation will be misinterpreted. As a consequence, we miss opportunities to generate positive feelings and establish closeness — qualities that tend to make feedback conversations less stressful.

Notice when the other person is seeking your attention — this can be as obvious as an invitation to lunch and as subtle as a glance seeking to make eye contact — and respond to these “bids.” You may not be able to fulfill the other person’s need for your focused attention at a given moment, but simply acknowledging it can help build a deeper, more connected relationship.

Develop a feedback-rich culture: While there’s much we can do individually and in our working relationships to improve the experience, the process of giving and receiving feedback will always be heavily influenced by the surrounding organizational culture. We should strive to create a culture in which feedback conversations are less stressful for all members of the organization. Among other steps, this involves giving and receiving feedback more frequently so that it becomes a normal aspect of organizational life, making it OK to both postpone feedback conversations until a better time, and ensuring that senior leaders walk the talk by offering and inviting direct feedback on a regular basis.

We often hear that feedback is “a gift” or “the breakfast of champions.” I don’t disagree with those sentiments, but I’ve stopped using those phrases because they fail to acknowledge how difficult the experience of receiving feedback can be. This can lead us to ignore our stress levels in feedback conversations, or, worse, feel required to tough it out even when we’re distressed past the point of effective learning. (As board-certified neurologist and middle school teacher Judy Willis has written, “[W]hen stress activates the brain’s affective filters…the learning process grinds to a halt.”)

I’m a confirmed believer in the value of pushing ourselves outside our comfort zones in order to grow, and feedback is an essential element in that process. But we should step into these conversations with a keen understanding of how we respond to stress, a plan for managing our stress levels, and an awareness of when we become too stressed to absorb feedback and learn from it. It’s a certainty that we’ll encounter some poorly-delivered feedback that renders a stressful experience even more distressing, so we need to prepare ourselves to receive some difficult feedback in the moment and strive to make our working relationships and organizational cultures safer, more trusting, and more feedback-friendly.

It’s Time to Retool HR, Not Split It

Let’s be clear. Ram Charan’s recommendation is wrong. CEOs and organization leaders who read only his column (or worse, only the title) and split HR as he suggests, will make a serious mistake that will destroy value for their shareholders and constituents. While he may be wrong, he may also be as wise as Solomon.

Wikipedia describes the parable of Solomon from the Bible: “The Judgment of Solomon refers to a story from the Hebrew Bible in which King Solomon of Israel ruled between two women both claiming to be the mother of a child by tricking the parties into revealing their true feelings.” In the parable, Solomon’s suggestion to cut the baby in half motivated the baby’s true mother to reveal herself by imploring Solomon to give the baby to the other woman, rather than see it killed. Everyone can see the harm in cutting a baby in half, so the maneuver works.

Splitting HR is also dangerous and counterproductive, but proposing it also points to the truth by vividly showing the challenge and importance of making leaders more sophisticated about HR and talent (“talent” includes human-centered capabilities, engagement, motivation, values and organization design).

The fact that splitting HR is dangerous and counterproductive has been well known for a long time, as shown by the quality and quantity of respectful rebuttals from my colleagues Dave Ulrich, Libby Sartain, Richard Antoine and many others, and by decades of research by my colleagues and me at the Center for Effective Organizations at University of Southern California and the Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies at Cornell University. Yet this evidence is apparently not well-known. A similar proposal to “Split Finance” would likely have been rejected out of hand by organization leaders (and Harvard Business Review editors), because it’s obvious that the Finance function must fit the organization strategy and leader capabilities. Why is this so obvious when it comes to Finance, and so obscure when it comes to HR?

The right question is not whether it’s time to split HR, but rather why are leaders so much less sophisticated about talent than about financial capital?

In the “The Capitalist’s Dilemma,” Clay Christensen and Derek van Bever suggest that leaders have been trained and socialized to their role as capitalists, and thus come to rely too heavily on familiar and traditional finance principles. That produces strategic missteps, because financial capital is increasingly commoditized, while talent is increasingly scarce and pivotal. Leaders must look beyond traditional finance systems to be more sophisticated about HR and talent. The “Split HR” column alludes to cross-pollination between HR and Finance, but tucking HR into the Finance function, as Charan suggests, is not the way.

My work with leaders from Finance, HR, and the C-Suite suggests instead that HR and talent decisions are optimized by “retooling HR” — adapting financial and other management frameworks to HR and talent decisions. For example:

• Retool leadership development using options theory and portfolio risk optimization.

• Retool talent development using a supply-chain framework to optimize talent flows like IBM.

• Retool performance management using engineering frameworks to optimize the return on improved performance (ROIP).

• Retool total rewards using product design and market segmentation to optimize the “deal” and balance customization and standardization.

• Retool employee turnover analytics by using inventory management frameworks that integrate employee acquisition, development and separation.

Retooling HR makes organization leaders smarter by applying their existing sophistication about finance, engineering, operations and marketing to HR and talent decisions. It does require that leaders reach across functional boundaries, but that’s different than simply placing compensation and benefits under the CFO.

The elegance of Ram Charan’s column is in revealing the troubling possibility that organization leaders might actually accept “splitting HR” as the solution to an important and complex issue. It shows the vital need to raise the HR and talent sophistication of today’s leaders. The HR profession can and should commit to creating a higher standard of talent stewardship, and to provide evidence-based frameworks, as the ones I’ve recommended above, as the foundation.

I commend Ram Charan for his wisdom in provoking such a useful dialogue, even as I implore leaders not to “cut the baby in half” by splitting HR out of ignorance. Instead, let’s retool HR, and accept the challenge to increase leader sophistication, and the quality of HR and talent decisions.

Experts Have No Idea If Robots Will Steal Your Job

Experts disagree about the future. That might seem unextraordinary, but it’s the conclusion of a new survey on robots from Pew, and it’s more significant than it sounds. For all the talk of “robots stealing jobs,” 2,551 experts surveyed were deeply divided over the following question:

Will networked, automated, artificial intelligence (AI) applications and robotic devices have displaced more jobs than they have created by 2025?

48% agreed with this pessimistic take, while a thin majority was more optimistic.

Perhaps the most obvious takeaway is that a grain of salt is needed whenever prognosticators claim to know which jobs will be automated and which won’t. These exercises are valuable in that they help us think through the role of automation in society, but the truth is we simply don’t know how many jobs of which kinds will be automated when.

To those in fear of being replaced by automation, the fact that experts are divided may seem like consolation – unfortunately, it’s anything but.

Instead, the second takeaway is that the skeptics are gaining ground. Conventional wisdom has long held that, while technology may displace workers in the short-term, it does not reduce employment over the long-term.

This encouraging bit of historical consensus was illustrated in a poll of economists taken this February by the University of Chicago. Only 2% of those surveyed believe that automation has reduced employment in the U.S.

Against this backdrop, Pew’s 50-50 split is more troubling. Some of the gap may reflect economists’ general optimism, but more than that, it signals the recognition that this wave of technological disruption could in fact be different.

Historically, fears of technology-driven unemployment have failed to materialize both because demand for goods and services continued to rise, and because workers learned new skills and so found new work. We might need fewer workers to produce food than we once did, but we’ve developed appetites for bigger houses, faster cars, and more elaborate entertainment that more than make up for the difference. Farmworkers eventually find employment producing those things, and society moves on.

In their recent book, The Second Machine Age, MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee challenge the assumption that this pattern will repeat itself, arguing that the sheer pace of today’s digital change threatens to leave many workers behind.

What if this process [of skill adjustment] takes a decade? And what if by then, technology has changed again? … Once one concedes that it takes time for workers and organizations to adjust to technical change, then it becomes apparent that accelerating technical change can lead to widening gaps and increasing possibilities for technological unemployment.

Much of the book is dedicated to making the case that technical change is accelerating, due to Moore’s Law, the observation that computing power roughly doubles every 18 months.

Several Pew respondents — experts from a wide range of technology-related fields — echoed this line of thinking. As technology consultant and futurist Bryan Alexander put it:

The education system is not well positioned to transform itself to help shape graduates who can ‘race against the machines.’ Not in time, and not at scale. Autodidacts will do well, as they always have done, but the broad masses of people are being prepared for the wrong economy.

There are counterpoints, of course, like those made recently here at HBR by Boston University’s James Bessen, who argues that technology eventually boosts demand for even less educated workers. Numerous Pew respondents agree. Internet pioneer and Google VP Vint Cerf put it succinctly:

Historically, technology has created more jobs than it destroys and there is no reason to think otherwise in this case. Someone has to make and service all these advanced devices.

Economist Tyler Cowen summed up his own thoughts on the subject, writing on his blog that:

The law of comparative advantage has not been repealed. Machines take away some jobs and create others, while producing more output overall.

But not unlike Moore’s Law, comparative advantage – the insight that workers shift to the tasks to which they are best suited – is not set in stone. Of the former, Brynjolfsson and McAfee write:

Moore’s Law is very different from the laws of physics that govern thermodynamics or Newtonian classical mechanics. Those laws describe how the universe works; they’re true no matter what we do. Moore’s Law, in contrast, is a statement about the work of the computer industry’s engineers and scientists; it’s an observation about how constant and successful their efforts have been.

Comparative advantage is more than just observation – it’s one of the most enduring findings of social science. It describes how economies work in a wide range of circumstances, but it is subject to revision. If the entire structure of the economy changes, thanks to technology, so too might the rules of comparative advantage.

In their book, Brynjolfsson and McAfee highlight how predictions made in 2004 on the basis of comparative advantage failed to predict even today’s division of labor between people and machines. Economists Frank Levy and Richard Murnane theorized that computers would handle arithmetic and rule-based work, while humans would be required for pattern recognition – like driving – as well as communication. Today, self-driving cars are well on their way to adoption and speech recognition is embedded in every smartphone.

The list of things that machines can do better than humans continues to grow, confounding our predictions. The jobs we think are safe may not be, and the ones we fear we’ll lose may be safer than we think.

How Uber Explains Our Economic Moment

Every once in a while you have one of those “microcosm experiences” that perfectly encapsulates the trends shaping our world. My most recent one came last week during an Uber ride.

I needed to get from my house in Cambridge to the WBUR studios in Boston so I could be a guest on local legend Christopher Lydon’s new show Radio Open Source. Ray Kurzweil, the other guest, was calling in from California. Instead of walking (too far), driving (no parking), or taking a cab (unreliable, inconvenient, and unpleasant), I did what a lot of people are doing these days: used my iPhone’s Uber app to summon a ride. Since I was paying for this one myself and I’m cheap, I chose uberX, where drivers use their private cars instead of limos. A couple minutes later a clean, new car pulled up; I hopped in, and off we went.

Because I’m interested in the peer economy I followed standard practice and asked the driver how long he’d been part of the Uber network and how he liked it. And I heard a very interesting story.

My driver said he’d been with Uber ever since he’d graduated from his master’s program in IT project management last year. This profession was, according to him, going through hard times. In the wake of the great recession steady jobs had been replaced by short-term contracts, and there weren’t even a lot of these to be had. As a result he was now competing against much more experienced people for each new gig that came up, and he hadn’t had a lot of success since graduating.

So to cover his monthly fixed costs of student loan payments (on more than $100k in debt), rent, and health care he was driving for Uber. A lot. He estimated that he spent more than 60 hours a week behind the wheel. This allowed him to pay his bills, but not to build up any real savings.

To which I say good for him, and for Uber. This is a guy who could be sitting around waiting for the dream job he’d gone to school for, collecting unemployment, defaulting on his loans, and/or dropping out of the labor force for good. Instead, he was working hard at a job that was available.

The days when high-paying factory jobs were available to anyone willing to work hard are long gone. My driver’s job existed because a small group of venture-backed entrepreneurs created a technology platform that matched up cars and drivers with people who were willing to pay for a ride. Most cars are chronically underutilized and in a time of high unemployment, so are too many people. Uber’s founders came up with a clever way to put them to work, and to do so while maintaining an enviable service and safety record.

Many other jobs today offer an unpalatable combination of low pay and low autonomy, with overbearing bosses and horrendous schedules set by someone else. Uber offers a great deal of autonomy, which is one of the reasons it appealed to my driver.

I call my ride a microcosm experience because it resonated with at least three other recent events. The first is Cambridge’s recent attempt to block Uber, which I wrote about here. Favoring the city’s truly lousy taxi incumbents over employment opportunities and service improvements brought by Uber is simply folly.

The second is the conversation I had with Kurzweil on the air once I got to the studio (the podcast is here). As far as I can tell he thinks that there are no real challenges accompanying today’s rapid tech progress. He predicted that there will be plenty of jobs, and that they’ll be fulfilling ones that allow people to pursue their passions. Well, my driver couldn’t find work doing what he went to school for, and he didn’t describe driving people around as his passion. My read of the evidence is that good, secure, fulfilling jobs are declining as we head deeper into the second machine age, not spreading throughout the economy.

Third is a recent “tweetstorm” from Marc Andreessen. He highlights previous predictions of technological unemployment, which turned out to be wrong. His point is that they failed to properly account for innovation and entrepreneurship like Uber, which finds new and unforeseen uses for human labor (his arguments are in some ways similar to Kurzweil’s, but with less emphasis on personal growth and fulfillment and more on economic opportunity).

Andreessen stresses that if we want solutions to our economic woes, we have to let innovation and entrepreneurship flourish. I couldn’t agree more; they’re absolutely necessary to fix what ails us.

I wish I shared Andreessen’s confidence that they’ll be sufficient, as well as necessary — that future rounds of innovation and entrepreneurship, abetted by pro-market policies, will take care of today’s un- and under-employment.

I certainly hope he’s right, but most of the long-term trends I see are pointing in the other direction (for a summary of the data I’m talking about, see this slideshare). I don’t think that’s just because business-hostile policies and a regulatory thicket are choking off job and wage growth. I think that it’s more fundamentally because technology is leaving a lot of workers behind as it races ahead.

Entrepreneurship and business innovation — like Uber — should be our first response to this phenomenon. But we might also need other ones. Education reform, tax policy changes, and a revised and improved social safety net might also well be needed. They’d benefit my Uber driver, and lots of others like him.

A Firm Handshake, a Lot of Bacteria

A strong handshake is almost twice as effective as a weak one in transferring bacteria such as E. coli from one person to another, according to a study conducted in the UK and reported in The New York Times. A moderately strong handshake, in turn, transfers about twice as many bacteria as a high-five. A fist bump is even more hygienic than a high-five.

Should Employers Ban Email After Work Hours?

Like many of you, I often work outside of regular office hours while at home, in the airport, and sometimes on vacation. Mobile technology has created a “new normal” work life for a lot of us: Gallup’s research reveals that nearly all full-time U.S. workers (96%) have access to a computer, smartphone, or tablet, with 86% using a smartphone or tablet or both. And a full two-thirds of Americans report that the amount of work they do outside normal working hours has increased “a little” to “a lot” because of mobile technology advances over the last decade.

But is this a net gain or net drain on our well-being? And how should leaders manage this after-hours work?

To answer these questions, it’s important to understand why we turn to mobile technology in the first place. For many people, it’s because we’re excited to share an idea with a colleague, or want to finish a task so it doesn’t become a burden the next day. Yes, taking care of work during non-work time may hurt our relationships with family and friends — but still, more than three-quarters of full-time workers tell Gallup that the ability to use mobile technology outside normal working hours is a somewhat to very positive development.

Going deeper, we found that just over a third of full-time workers say they frequently check email outside normal working hours — and those who do are 17% more likely to report better overall lives compared with those who say they never check email outside work. This finding holds even after controlling for differences in income, age, gender, education, and other demographics. Similarly, those who spend seven or more hours checking their email outside work during a typical week are more likely to rate their overall lives highly than those who report zero hours of this activity.

But here’s the conundrum: About half of workers who report checking email frequently outside work are also more likely to report having “a lot of stress” yesterday, compared with just one-third of those who never do.

In other words, the “evaluating self” disagrees with the “experiencing self.” The “evaluating self” probably says life is better because we have the flexibility to check email when we want, while the “experiencing self” feels the stress associated with the extra work, pressure, or guilt during our after-hours working time.

This inner conflict is not new to psychologists. For example, research suggests our “two selves” also differ in how they interpret having money and children. Being a parent and having more money is associated with higher life evaluations; but above a baseline of income, having more money doesn’t relate to less daily stress, and having kids brings more daily stress, on average. The “evaluating self” responds to status, while the “experiencing self” responds to daily and momentary life.

Thus, while checking email frequently appears to be stressful, it is also most likely associated with status and perceived importance.

So for optimal workplace well-being, what should employers do in light of this conundrum? Expect workers to check in during non-normal working hours? Or implement policies that discourage work during non-normal work times?

Sure, employees who say their employer expects them to check email outside normal working hours report stress 19% more frequently than those whose employer doesn’t expect them to check email. This might lead employers to think they should put the needs of the “experiencing self” of the employee ahead of the “evaluating self” and place specific parameters around expectations that employees check in during off-hours.

Not so fast.

Problems arise when companies make such policy decisions without considering whether their employees are engaged. If we assume work can be engaging and rewarding, rather than a necessary burden, our assumptions about people and policy become quite different. Gallup’s research has found that high levels of engagement are more important than specific well-being policies.

Gallup has identified three types of workers: engaged, not engaged, and actively disengaged. Thirty percent of U.S. workers are engaged — they are involved in and enthusiastic about their work and company. At 52%, not engaged workers make up the vast majority of the U.S. workplace — they are indifferent and basically just show up, do the minimum required, get their paycheck, and go home. Actively disengaged workers comprise 18% of the U.S. workforce and actually work against the aims of the organization. (Gallup measures engagement through 12 elements that explain differences between highly productive and less productive workplaces.)

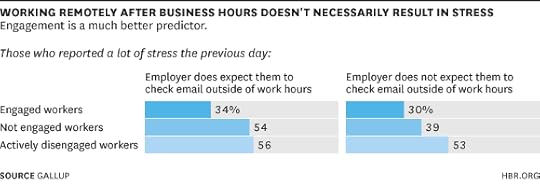

Daily stress is significantly lower for engaged workers and higher for actively disengaged workers, regardless of whether their employer expects them to check email during non-work hours or not. And it is the vast swath of “not engaged” or “indifferent” workers who are most influenced by policy decisions of this nature. Among the “not engaged” workers who say their employer expects them to check email outside normal working hours, 54% report a lot of stress the previous day. Of those who say their employer does not expect them to check email, 39% report a lot of stress.

These findings suggest workers will view their company’s policy about mobile technology through the filter of their own engagement. Thus, instead of tinkering with their policies, companies would be better off developing a strategy to engage more of their employees. For instance, while more hours worked, less vacation time taken, and less opportunity for flextime generally relate to lower well-being in our studies, that doesn’t hold true when workers are engaged in the workplace. It turns out that among engaged employees, their well-being remains high, regardless of these types of policies. As an extreme example, employees with six or more weeks of annual vacation time who are actively disengaged in their work and workplace have lower overall well-being than those who are engaged and have less than one week of vacation time.

Similarly, while long commutes generally relate to lower well-being in the average non-engaged worker, it isn’t true for those who are engaged. Our research shows that well-being levels are similar among engaged workers, regardless of their commute time. These findings underscore the importance of employee engagement to workers’ well-being in the workplace. Engaged workers are more productive and profitable, are more likely to show up to work regularly and make a difference with customers, and are loyal, advocating partners to the organization. They view their lives more positively because they work in organizations that get the most out of their talents.

While just 30% of employees nationally and 13% internationally are engaged, it doesn’t have to be that way. Many organizations — even very large international organizations— have more than doubled these percentages by not accepting a fatalistic status quo. Through quality measurement, accountability, developmental plans, good communication, and aligned strategy, they have developed environments where the norm is for workers to be engaged rather than indifferent. This starts and ends with hiring and developing quality managers who have the natural talents and skills to engage and develop each person they manage, thereby improving how people both evaluate their lives and experience their days.

Most full-time employees consider the option to use mobile technology away from work an advantage rather than a hindrance, probably because of the flexibility it invites. With the help of great managers, engaged employees leverage this flexibility without feeling extra stress. And while organizations can set blanket policies that assume indifference among employees, they might be better off engaging them first. Policies are important — but they shouldn’t be any manager’s starting point.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers