Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1384

August 7, 2014

The Art of Managing Science

J. Craig Venter, the biologist who led the effort to sequence human DNA, on unlocking the human genome and the importance of building extraordinary teams for long-term results.

A Fairer Way of Giving Credit Where It’s Due

People have a deep need to feel that their contributions to the group are acknowledged — even celebrated. Financial compensation alone cannot satisfy that requirement.

Fairly assigning credit, however, is difficult. In a knowledge economy, the intellectual origin of a given idea is very hard to document. Where new concepts are often conceived collaboratively, how do we know where credit is due? If one employee insists that he or she made more of an effort or contributed more to an outcome than another, how can we verify that? Getting employees to even discuss the topic can be difficult given that many feel conflicted about it: They want to be acknowledged but are embarrassed by their desire for external recognition.

We have tested an approach that has seemed to address these issues in our jobs in the nonprofit and government sectors, where financial incentives can be scarce and other forms of recognition, therefore, are especially important. This method seeks to both eliminate resentments and arguments over recognition and foster collaboration toward better results. It includes these four elements:

Tie individual recognition to group performance. When we’ve tied individual recognition to the overall success of the group, we’ve been able to reduce tension over who did what while reinforcing teamwork. A similar approach is used in the National Hockey League, where a “plus-minus” system calculates how often a skater is on the ice when a goal happens, awards a point when the team scores and subtracts one when the opponent does. Over the course of a season or a career a player’s cumulative plus-minus score estimates how important his presence is to the overall success of the team. (Bobby Orr, the greatest defenseman in the league’s history, was a staggering “plus 597” for his career, meaning that when he was playing, the team scored 597 more goals than it surrendered.)

Recognize outcomes. Our experience has shown that the most successful teams align their recognition systems with the outcomes they want and periodically reassess the outcomes to determine whether they are still relevant. By contrast, we have seen many struggling teams that award recognition for activity metrics (e.g., length of service, attendance) that may not have direct bearing on those goals. Johns Hopkins Medical, the internationally renowned health care system, has recently taken a bold step toward rewarding outcomes. Instead of pegging academic advancement solely to peer-reviewed publication, it now provides academic physicians with points for a successful project to improve patient care or outcomes, regardless of publication.

When hiring, focus more on track records and less on pedigree. Let’s face it, people often are more impressed by an Ivy League degree than one conferred by a run-of-the-mill state school. While such credentials can impart some useful information about how hard job candidates have worked or their intelligence, the story of the book-smart Ivy Leaguer who enters an organization only to be flummoxed as he tries to put theory into practice is almost a cliché. One commonsensical approach for dealing with this issue is to winnow candidates for a position on the basis of their record in producing outcomes and only then consider their pedigree. Many organizations, of course, also rigorously reassess new hires at the end of a probationary to make sure they really can contribute and fit the organization’s culture.

Embrace risk-taking and failure. In organizations where failure is viewed as a threat to recognition, conservatism and orthodoxy thrive. By contrast, many successful organizations value failure as integral to learning and improvement. Explicit recognition of failure offers an opportunity to demonstrate its importance. For decades NASA has rewarded admission of failure (versus hiding potentially problematic results). Likewise, the advertising agency Grey bestows a Heroic Failure Award, reinforcing the company’s emphasis on experimentation. Managers can put this into practice by dedicating time for post-mortem “hotwash” meetings, providing an opportunity to internally recognize team efforts and embrace all aspects of a project.

To be sure, the assignment of credit can never be perfect. Every organizational context will be different and bring with it its own challenges. However, when managers look beyond these hurdles and dedicate the time and effort to get this right – thoughtfully managing an economy of recognition in their organization – they will strengthen relationships, boost team morale, and have a tangible impact on the organization’s performance.

The Best Leaders “Talk the Walk”

One of the most ubiquitous aphorisms in business is that the best leaders understand the need to “walk the talk” — that is, their behavior and day-to-day actions have to match the aspirations they have for their colleagues and organization. But the more time I spend with game-changing innovators and high-performing companies, the more I appreciate the need for leaders to “talk the walk” — that is, to be able to explain, in language that is unique to their field and compelling to their colleagues and customers, why what they do matters and how they expect to win. The only sustainable form of business leadership is thought leadership. And leaders that think differently about their business invariably talk about it differently as well.

I saw the power of language come to life earlier this summer when I made an eye-opening visit to a day-long orientation held every six weeks or so for new employees of Quicken Loans, the online mortgage lender based in Detroit and owned by high-profile billionaire Dan Gilbert. Quicken Loans is known for lots of things, from torrid growth (the company closed a record $80 billion worth of home loans last year, up from $70 billion in 2012), to much-praised customer service (it is a perennial JD Power customer-satisfaction winner), to . But behind it all, at the heart of the company’s approach to strategy, service, and culture, is a language system that defines life inside the organization and reminds everyone what really drives success.

Founder Dan Gilbert and CEO Bill Emerson call this language the company’s “Isms” — which is why the rollicking, fast-paced, eight-hour orientation session is called “Isms in Action.” Gilbert and Emerson, who present separately and together over the entire eight hours — an executive teaching marathon unlike anything I have seen before — march employees through the company’s 18 Isms, with a combination of slide shows, stand-up humor, war stories from the trenches, and unabashed appeals to the heart. A few of the Isms get covered in 10 or 15 minutes, some take an hour. But the end result is a full-day immersion in a whole new language — a “vocabulary of competition” that sets the company apart in the marketplace and holds people together in the workplace.

On the day I attended, more than a thousand participants crowded into a ballroom in the Marriott Renaissance Center on the banks of the Detroit River. Gilbert and Emerson urged their new colleagues to embrace the idea that, “The inches we need are everywhere around us” — in other words, there are countless small opportunities for people to tweak a product, or improve a process, that lead to big wins in the marketplace. They insisted, no excuses allowed, that everyone agree with the Ism, “Responding with a sense of urgency is the ante to play.” Gilbert personally emphasized again and again, sometimes with jokes, sometimes with withering disdain, the absolute requirement that Quicken employees return every phone call and every email on the same business day they were received. “We are zealots about this,” he thundered, “we are on the lunatic fringe. And if you’re ‘too busy’ to do it, I’ll do it for you” — at which point he gave out his direct-dial extension and promised to return phone calls for any overwhelmed colleagues.

On and on it went — funny stories, sure, sage pieces of advice, a quick history of the company. But mainly an urgent iteration ands reiteration of the company’s Isms:

“Numbers and money follow, they do not lead.”

“Innovation is rewarded, execution is worshipped.”

“Simplicity is genius.”

In business leadership, as in all forms of leadership, words matter. Indeed, several of the attendees with whom I spoke weren’t new employees at all. They’d come back for a refresher, a reminder, an opportunity to spend a day reacquainting themselves with the language that defines life at Quicken Loans, a chance to spend a day watching the founder and the CEO “talk the walk.”

So ask yourself, as you try to lead an organization, or a business unit, or a department: Have you developed a vocabulary of competition that helps everyone understand what makes your company or team special and what it takes for them to be at their best? Can you explain, in a language all your own, what separates you from the pack and why you expect to win? Even as you make sure to walk the talk, do you know how to talk the walk?

Is Apple Losing its Creative Mojo?

We now have a date: September 9, the day that iPhone6 is expected to be launched. While there is a still a month to go , the iPhone launch circus and its usual cast of characters are all already in town. The tech media is leaping on every bit of information that can be inferred from the Apple supply chain about the potential specs of the phone (for the record we are expecting Apple to introduce a big screen brother to the current phone and produce it in record numbers).

But the business press is decidedly less excited: a bigger iPhone is hardly the category busting game changer they have been calling for. Some have even gone as far as speculating that Apple under Tim Cook has lost its creative mojo.

Is Tim Cook’s Apple really that different from Steve Job’s? A careful analysis of the facts suggests not:

Apple is rarely the first entrant. If we look at the last fifteen years, Apple was by no means an early entrant in digital music players, nor in smartphones (see Blackberry). In fact, each of these markets had achieved a much higher level of customer interest (and frustration with the existing offerings) before Apple came in with better designed products. Neither smart-watches, smart TVs nor payments are at the stage that music players or smartphones were before Apple entered these new categories. And with the unimpressive offerings from some of the early movers in these categories (for example Samsung’s smart watch), Apple has plenty of time. Nor are its current businesses doing too badly.

Apple does it right rather than fast. It has always defied the popular Silicon Valley adage of failing often and failing fast. While this is great advice for a cash-constrained startup with little reputation, brand image, or a large group of premium-paying loyal customers to loose, this is not a smart strategy for Apple. Apple has defined itself as a brand that delivers beautiful, integrated almost magical experiences on day 1, and not on version 3.1. This is perhaps its greatest asset and preserving it requires Apple to make sure the ecosystems, technology, product design all meet a much higher standard than any of its competitors. Apple will release these products only when they meet its rightfully high standards.

While in these two ways Apple under Tim Cook is no different than Apple under Steve Jobs, there is one aspect in which Tim Cook has differentiated himself: he has laid out the groundwork for creating multiple options for categories to disrupt.

Behind the fanfare, Apple has positioned itself very well for entering many new categories. The iHealth platform in iOS8 will give it a lot of user insight before any smart-watch is launched. Its new content distribution network sets Apple for delivering superior connected TV experiences, for cloud storage, etc. The iBeacon technology sets them for some big stuff in revolutionizing the retail experience (as does the hiring of Musa Tariq from Burberry). And finally,Touch ID has set them up for online payments.

While no one knows the intended purpose of all these foundational initiatives, each of them provides Apple options, options to watch what happens, pick the most promising opportunities, and create category-busting products. Likely, Apple won’t enter all of the markets mentioned above, but it will perhaps wait to see which of these opportunities develops best in terms of Apple’s ability to offer a disruptively superior experience to the status quo.

In this, we see a new approach to innovation at Apple, a risk driven approach where Apple sows many seeds, hedges its bets and will reap the most promising opportunity. This is decidedly different and likely superior to Apple’s know-it-all approach under Steve Jobs.

What to Do If Your Team Is in a Rut

Another brainstorming session, another slew of tired ideas. Your team is in a rut, but what can you do about it? How can you push everyone to be more creative? Where should you seek inspiration? What’s the best way to bring in new perspectives? And finally: how do you prevent the group from getting stuck again?

What the Experts Say

Teams get stale from time to time for all sorts of reasons. After all, everyone is “seeing the same data, interacting with the same people, and having the same conversations, so it’s no surprise that the ideas coming out feel as though they’ve all been done before,” says Scott Anthony, the managing partner of Innosight and the author of The First Mile. But you can get your people back into the groove with a little work, says Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg, a partner at The Innovation Architects, the advisory firm, and the coauthor of Innovation as Usual. “Sometimes you need to rethink what you’re doing.” Here are some ways to get your team’s creative juices flowing.

Diagnose and fix any obvious problems

The first step is to “take a step back and diagnose the problem,” suggests Wedell-Wedellsborg. “Observe what’s going on and ask other people’s opinions.” Think about when, where, and how your team has been most innovative in the past. Can you recreate that environment or group dynamic? “Figure out how people share ideas, and how open others are to those ideas,” he says. Also look at ideas that were generated in the past and see if any are worth resuscitating. “Maybe it was a good idea before its time or maybe it was an idea that was not managed well,” says Anthony. “You’re not looking for the perfect idea, it’s what you do with the idea that matters.”

Focus your team’s attention

Open brainstorming sessions with lofty goals like generating “500 New Ideas” are fine in theory, but in practice they are often ineffective and inefficient. “You end up with a lot of stuff that’s not relevant,” says Wedell-Wedellsborg. Instead, direct your team’s attention toward solving a narrow problem — for example, ways to fix a specific customer issue or to generate 2% cost savings in your division. “Define the task so your team is very clear on what it is trying to accomplish,” says Anthony. Management literature tends to associate chaos with creativity but in fact “constraints are the greatest enablers of creativity,” he adds.

Bring in different points of view

Most of us tend to live in filtered worlds — we read the same papers and magazines, listen to the same newscasts, get our daily updates from the same RSS and Twitter feeds, and have lunch with the same people. “But great ideas come from people who are immersed in more worlds than just their own,” says Wedell-Wedellsborg. Create opportunities to expose your team to different perspectives and points of view. Anthony suggests touring the offices of companies in different industries or inviting employees from other parts of your business to regularly present ideas to your team. The point is “to touch and interact with people who are thinking differently,” he says. “The magic happens when different skills and mindsets collide.”

Share relatable examples of success

The Steve Jobs-Mark Zuckerberg-Richard Branson “genius” innovation narrative is omnipresent in business blogs, books, and magazines. But to most work-a-day folks, those figures are “not as inspirational as you might think,” according to Wedell-Wedellsborg. “If you have a normal job — like most of us do — these examples can seem terribly ambitious and too remote.” For relatable inspiration, offer success stories that are closer to home. “Shine a spotlight on innovative things that have already been done in your organization,” says Anthony. The message is: “This is something we can do; your peers have done it.”

Conquer your team’s fear of failure

One of the most common reasons for stagnation is not your team’s lack of ideas but their fear that the ones they have aren’t any good. This fear of failure is so pervasive that many employees choose not to voice or champion their opinions, which, of course, hinders innovation. Leaders must therefore “manage the politics” around brainstorming, says Wedell-Wedellsborg. “Make sure there’s room for people to share ideas in a way that’s under the corporate radar.” Anthony agrees. You have to cultivate a “safe environment that is as tolerable to learning as possible,” he explains.

Create avenues for ideas to have an impact

Ideas only matter if you act on them. “People get cynical fast after they have a fun and empowering brainstorming session and then nothing happens,” says Anthony. As a manager, you need to commit to moving innovation forward. He suggests setting aside a small budget to create rough prototypes and simulations, or relieving workers of some duties to free up their time for new projects. Wedell-Wedellsborg also recommends testing ideas on a small scale. “Force people to come up with practical experiments so they then get honest feedback about what works and what doesn’t,” he says.

Avoid using the word “innovation”

In some organizations, you can still talk about an “innovation initiative’ and create excitement, but in most companies, the term is overused and has “been talked to death,” says Wedell-Wedellsborg. “If you say it, people will look at you with a vague stare.” Instead of the i-word, encourage your team in language that’s meaningful to them. “Don’t frame it to your team as coming up with ideas for an ‘Employee Retention Innovation Plan.’ Frame it as a ‘Making Your Company a Better Place to Work Strategy.’ That’s something most people can get on board with.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Create regular opportunities to expose your team members to new ideas and perspectives

Cultivate a culture where your team feels confident sharing their rough ideas without fear of failure

Develop a plan for action by setting aside a modest budget for experimenting with new ideas

Don’t:

Host vague brainstorming sessions with grandiose goals; rather, focus your team’s attention toward solving a particular problem

Hold up unattainable examples of innovation success; find models that are relatable

Persist in using tired business-speak; frame ideas using language that will resonate with your team

Case study #1: Acknowledge risks and empower team members to speak up

In October 2012, Patti Pao, the founder and CEO of Restorsea, the luxury beauty brand, and her team were at a crossroads. Restoresea had raised a little over $10 million in funding and was the top selling skincare brand at the Lab at Bergdorf Goodman. But because of the costs associated with maintaining a presence in the brick-and-mortar department store — including commission for salespeople, samples, and advertising in catalogs and mailers — the company was losing money there. Meanwhile, Restorsea’s website was selling 12-15 times more than it sold at Bergdorf’s. “My team and I decided the internet needed to be our primary channel of distribution,” Patti says.

In an industry where buying decisions are made based on shoppers feeling, smelling, and experiencing products, it was “a big risk.” But she trusted in the group’s ability to figure out how to best execute the new strategy. Her first step was to make the group feel supported and encouraged by acknowledging that they were embarking on a scary challenge together. “I fostered an environment where people were okay about holding hands and jumping off a cliff,” she explains. ” I didn’t want my team to be afraid to fail; I wanted people to be more afraid of not moving swiftly.”

The team came up with several successful ideas and initiatives such as a Living Social partnership to build awareness of the brand, a blogger affiliate initiative to generate PR and editorial support, and a “Share the Love” program, where loyal customers are invited to send full-size day cream and eye cream to three of their friends and family members. Since the shift toward ecommerce, Restorsea has raised an additional $45 million in funding and is “tremendously more profitable,” she says.

Case study #2: Cultivate a culture of confidence and recognition for a job well done

Carl Galioto, the managing principal of the New York office of HOK, the design, architecture, engineering, and planning firm, says he takes a “very personal approach” to promoting creativity on his team. “I manage architects so in some ways I have an unfair advantage — they are generally creative and team-oriented people,” says Carl, who helped design One and Seven World Trade Center as well as JFK International Airport and Harlem Hospital Center.

At the same time, he works hard to “cultivate a culture of confidence” by recognizing each employee for what he or she has accomplished and achieved. “I talk with each member of the group one-on-one [and] tell them how much I value their opinion and what they’ve done before — even small things like process improvements,” he explains. “I say: ‘Remember when you figured out a better way to X?’ Then I try to push them to be even bolder.”

A few years ago, Carl and his team set out to develop HOK’s platform for digital design tools, building SMART, which leverages 3D modeling. To maximize creativity and excitement, Carl articulated a vision with a series of goals and then empowered his team to “propose an organization, a refinement of goals, and a destination” over a defined three-year period.

“They had creative freedom and the responsibility for achieving the goals on time and on budget,” he explains. They succeeded, and were fully credited and acknowledged for their efforts.

The Financial Risk of Living a Long Time

People nearing the end of their careers can potentially lose 5% to 10% of their retirement wealth, or the equivalent of 2 to 5 years’ labor, by failing to annuitize their savings or annuitizing too early, according to an estimate by Alessandro Previtero of Ivey Business School in Canada. By providing a guaranteed income for life, an annuity is essentially an insurance policy against outliving one’s retirement savings. In a study, Previtero found that when stocks are rising, people are less likely to purchase annuities offered by their employers.

Even the Tiniest Error Can Cost a Company Millions

Think of your data as a mound of rocks. All managers know they need to be able to sort the rocks and count the rocks; but the best ones can also turn over each rock to see what crawls out. By doing so, you can make some startling discoveries.

An example of this go-deeper approach comes from AT&T, where Bob Pautke, manager of Access Financial Assurance, and his team were charged with ensuring that AT&T paid the right amount for certain services it purchased from other telephone companies. Their job was easy to define but tough to perform. The services were complex, the sheer number of invoices was high, and there were many errors. AT&T feared that it was overpaying, possibly by tens of millions of dollars.

The obvious approach was to search for errors by inspecting each invoice using internal data sources that estimated each invoice. Unfortunately, this approach was not up to the challenge. While some errors were easy to spot, internal sources often proved unreliable, and many suspected errors leaked through. Further, proving an invoice incorrect was expensive, and resolution took too long.

A new way of approaching the problem was needed, so Bob and his team expanded their scope from inspecting the invoices themselves to evaluating the entire process that created them. You’ll get correct invoices when the end-to-end process works perfectly, the first time and every time. Conversely, an error on an invoice had to stem from an error in the process.

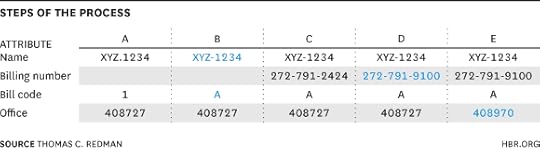

Since nobody knew precisely what happened as the work proceeded, Bob and his team conducted a tracking study by simply observing what happened to the data created and processed at each step. To start, Bob’s team compiled 20 tracked records and studied them, looking at individual records and calling out anomalies. In each case, they identified something that “just didn’t look right.” The figure below features a portion of one of the tracked records and highlights, in blue, four instances where something changed that they did not expect to change as this data wended its way through the process. (Note: Data has been disguised to protect AT&T’s proprietary information.)

The first two changes (from XYZ.1234 to XYZ-1234 and from 1 to A) involved reformatting the data during Step B. They discovered a number of small changes like this as they looked through the data. Some were annoying, but none appeared to impact invoices. The other two changes, though, were more substantial. The billing number and office number changed mid-process. These changed the meaning in the data and impacted the invoice.

While this tracking method had not yet cracked the original business problem — to ensure that AT&T paid the right amount for services — it had produced plenty of potentially interesting “rocks” to turn over. In so doing, it changed the dialog. The questions were no longer simply, Is this invoice correct? and If not, how much is it off by? Instead, they had become, How bad is the process? Where is it broken? and How do we fix it? Sometimes when you turn over a rock, what emerges is not an answer to an existing question, but a better question.

Thus, Bob and his team sought to develop deeper insights into the frequency and severity of errors. They automated data collection and began to look for overarching patterns.

They started by using visuals such as time-series and Pareto plots to gain insights into such questions. The figure below helped answer the first question: How bad is the process? It showed that, on average, only 40% of the data records made it all the way through the process without error. Clearly, underlying process problems were enormous and pervasive.

As the extent of the problem became clearer, they turned their attention to the second issue: where errors occurred. In many cases, as you see in the figure labeled “Process Performance By Administrative Region,” the visuals yielded no particular insight. But the figure labeled “Process Performance By Attribute” proved more fruitful — it revealed that the vast majority of problems occurred in a relatively few attributes.

In a separate analysis, Bob and his team discovered that the vast majority of problems occurred on the interfaces between steps C and D, and D and E. Then, combining this insight with what they already knew about attributes, they were able to identify exactly where to target improvements, in effect providing a very precise answer to where the process was broken.

Improvement teams were then tasked with addressing how to fix the issues. As these teams completed their work, end-to-end process performance and invoice quality improved. Bob’s original task — identifying if the company was accurately paying what was owed — was now much easier. And, not surprisingly, the company saved tens of millions along the way.

You can take these steps in your own organization, as you dive into your data.

First, identify the business problem and ask yourself what hidden assumptions constrain your efforts to address that problem. In Bob’s case, they were looking to discover whether they were paying exactly what was owed but were unsure whether verifying invoices was the best way to do so.

Then, find or create relevant data and test those assumptions. Bob’s team was able to track records, testing whether process errors lead to invoice errors.

Next, dig into the data and let new questions emerge. In their search, Bob’s team discovered three more important questions, which revealed larger process issues.

Last, find solutions. Now that the data had brought issues to the surface, take steps to fix these problems — and improve your business in the process.

There is nothing magical about any of this. While Bob and his team were smart, articulate, and hardworking, they had only the most rudimentary quantitative skills when they started. But they learned a few basic ways to turn over rocks and challenge conventional wisdom, and new and unexpected information crawled out.

August 6, 2014

4 Mistakes Marketers Make When Trying to Go “Viral”

Can we agree to kill the word “viral” – unless it’s referring to something that leads you to call a doctor, or download a security patch?

The problem with this term is that it suggests there’s something inherent in the content itself that makes it travel. The virus, once released into the wild oceans of social media, preys on its victims. In fact, quite the opposite is the case: unlike viruses, people actively choose to engage with marketing messages and to share them (or not) with friends.

That’s why some have suggested describing what the best marketers create as spreadable media rather than viral content. While less, ahem, catchy as term, it’s a healthy reminder that, while marketers create the media, it’s people who do the actual spreading.

Marketing has always been about meanings created between a company, their audience and a wider culture or community — as the great ad man Jeremy Bullmore once said, “People build brands the way birds build nests, from scraps and straws they chance upon.” The difference is people are now able to create brand messages and distribute them to others at scale like never before. The reverse is also true: as social networks increasingly become the primary vehicle for content discovery, companies that don’t involve audiences in the creation and spread of their messaging will not be found.

Taking this concept a step further, the anthropologist Grant McCracken has suggested we need to shift the vernacular for how we refer to the agents of virality. Rather than apply passive descriptors like “audience”, “consumers” or “targets”, McCracken suggests we use the term multiplier instead. As in, “Who are the multipliers we are trying to reach with this campaign?”

Thinking of the people you are reaching as multipliers and your content as “spreadable” rather than “viral” will help you avoid several all-too-common pitfalls:

Mistake 1: Trying to start from third gear. It’s hard to predict what will be spread. Yet how often have you labored over a video or an infographic stalled on social, despite spending promotional dollars to generate traffic for it?

You need to build momentum before shifting into higher gears. Create a test budget to put different articles, videos, charts, and headlines in front of potential multipliers before investing more heavily behind them. The fastest path to maximum acceleration is to start in lower gears and then upshift once you see something being spread at above normal rates, or else stop spending and move on to the next test. With Facebook, it’s even possible to test posts among small groups and not have those test messages appear on your brand’s published Timeline – so-called “dark posts”.

Mistake 2. Asking people to “share” as if sharing itself were the goal. If you are of the mindset that your content is inherently “viral”, then you might expect people to share it automatically. If you’re a not-for-profit raising awareness around issues people care deeply about –inequality, pollution, cancer – you may be right. But If you’re an IT services company, it’s a lot trickier. Most people don’t share simply for the sake of sharing. Content that is spreadable, on the other hand, is sharing with a purpose.

Choose a topic or cause related to your brand that inspires passion and then find ways to involve people in it. Remember that people are a lot more likely to spread media when they are part of in some way. Think of mechanics to involve them, like a social pledge or petition, that call them to action around the topic, as opposed to merely asking them to “share on social” without a reason why.

Mistake 3. Assuming your work is done when you hit “publish.” There are petabytes of valuable content on the web that have only been seen by a handful of people. No matter how great the story, the web can be brutal on old content, where search and social algorithms favor recency as a key factor determining what gets seen by your multipliers. According to a Simplereach study, the average article reaches half of its total social referrals within 9 hours on Facebook (and in even less time on Twitter). Keep the story alive with additional tweets and posts, focusing on different angles and ongoing developments, and invite your multipliers to keep the story alive with you. (Thinking of people as “multipliers” instead of “consumers” makes it clear, notes McCracken, “we depend on them to complete the work.”)

For example, an article published on TheDodo.com about scientists spotting a 103-year-old Orca off the Pacific coast – and why that was bad news for SeaWorld — generated 900,000 Facebook likes in its first week. That’s great, but even better was that 100 readers contributed their own full-length posts through theDodo.com’s guest blogging platform, of which 20 articles generated more than 50,000 Facebook likes each. In total, that’s more sharing of articles contributed by multipliers than of the original post itself! While traffic to the Orca article page has slowed, the subject overall continues to generate significant amounts of traffic to theDodo.com as of two months later and is nearing 1 million pledges to the cause it supports.

Mistake 4. Failing to develop relationships with your multipliers. “Viral” is often fleeting; someone stumbles across a widely shared video, watches part of it, and the marketer never has the opportunity to figure out who he is. The relationship ends there. Instead, identify your multipliers. Get to know them. Encourage them to share often. You don’t need to offer financial rewards (e.g. “Tweet five times more for a free coffee”) to get great results. Often simply the act of acknowledging them publicly, either by featuring them on your website or responding to them on social, is enough to generate an additional act of multiplication. Where possible, you should also capture their email addresses so you’ll be able to deepen the relationship further with truly useful updates, offers, and calls to action.

When we stop thinking of content as viral and start thinking of it as spreadable, it helps us refocus on our relationship with the community. When it comes to multiplying your message, that’s just as important as creating great content.

The Question to Ask Before Hiring a Data Scientist

When hiring data scientists, there’s nothing more frustrating than making the wrong hire. Data scientists are in notoriously high demand, hard to attract, and command large salaries — compounding the cost of a mistake. At The Data Incubator, we’ve talked to dozens of employers looking to hire data scientists from our training program, from large corporates like Pfizer and JPMorgan Chase to smaller tech startups like Foursquare and Upstart. Employers that didn’t have good hiring experiences in the past often failed to ask a key question:

Is your data scientist producing analytics for machines or humans?

This distinction is important across organizations, industries, and job titles (our fellows are being placed at jobs with titles that range from Quant to Data Scientist to Analyst to Statistician). Unfortunately, most hiring managers conflate the types of talent and temperament necessary for these roles.

While this isn’t the only distinction among data scientists, it’s one of the biggest when it comes to hiring. Here’s the difference, and why it matters:

Analytics for machines: In this case, the ultimate decision maker and consumer of the analysis is a computer. Online ad or content targeting, algorithmic trading, product recommendations are just a few examples.

These data scientists are building very complex models ingesting enormous data sets and trying to extract subtle signals with machine learning and sophisticated algorithms. These digital models act on their own, choosing which ads to display, making recommendations to users, or automatically trading in the stock market, often in less than the blink of an eye.

Data scientists who produce analysis for computers need exceptionally strong mathematical, statistical, and computational fluency to build models that can quickly make good predictions. They usually operate with clear metrics (such as profits, clicks, purchases) and can piece together a myriad of technical tricks to build very sophisticated models that drive performance. When even small gains are aggregated across millions of users and trillions of events, their efforts can result in huge gains in revenue.

Analytics for humans: The ultimate decision maker and consumer of the analysis here is another human. Analyzing the effectiveness of products, understanding user growth and retention, producing reports for clients are just a few examples of the work these data scientists do.

They might be sifting through the same large data sets as their analytics-for-machines counterparts, but the results of their models and predictions are delivered to a human decision maker (often a non data-scientist) who has to make product or business decisions based on these recommendations.

Data scientists who produce results for people have to think about how to tell a story from the data. Because they have to explain their results to others — particularly those who are not as well versed in data science — they might deliberately choose simpler models over more accurate but overly complex ones. They have to be comfortable drawing higher-level conclusions — the “how” and “why.” These aren’t as easily observed in the data as the clear metrics enjoyed by their analytics-for-machines counterparts.

It’s important to get the right person for either job. We find that the typical profile of a data scientist who produces analytics for machines is someone with a natural science, mathematics, or engineering background (often at the PhD level) with the deep mathematical and computational background necessary to do the really high-powered work. Without the necessary technical skills, candidates will either fail at handling the large amounts of data or apply overly simplistic models that don’t capture the data’s full value.

However, these same people may not be suited to produce analytics for humans. Putting a team of MIT-trained physicists in a role where they are constrained to use “simple” models that management can understand will not be the best use of their talents, especially if they’re thirsting for a “deep” machine-learning challenge. On the other hand, social and medical scientists (again, often at the PhD level) are really well trained at understanding the “how” and “why” and often thrive on this kind of intellectual challenge.

Data scientists with hard science backgrounds have traditionally gotten a lot of attention in the press. In part, this is romanticizing the unknown — mysterious models that magically trade stocks or intuitively understand user preferences are sexier than the tedious work of thinking really hard about causality, sample bias, and the “how” or “why” of your data. But the latter could be what you really need from a data scientist. By asking this key question ahead of the hiring process, companies can go beyond the hype and find the right data scientists for their specific needs.

Save Your Next Staff Meeting From Itself

While many leaders see staff meetings as vital to the success of their organization, most employees see them as a painful waste of time. As a result, employees arrive or leave whenever they wish; check their emails; doodle; or use the time to make to-do lists of all the things they’re not getting done in your meeting. The outcome is a lethargic downward spiral.

With other types of meetings, leaders can mitigate this effect by keeping the attendee list as narrow as possible, and only calling a meeting when there’s something to discuss. But a staff meeting is a different beast altogether: by definition, it includes the entire team. And it’s usually a monthly or weekly recurring meeting (because scheduling so many people on short notice would be impossible).

Both of these factors mean that for the leader trying to run a good staff meeting, the deck is already stacked against you. But there are some common meeting pitfalls that are especially problematic in staff meetings. Avoid them, and you’ll make your staff meetings more useful and energizing:

Mistake 1: No clear objective. The luxury of a recurring meeting lets busy leaders get their teams together without having to think of a reason to do so. Yet each staff meeting should have a clear purpose: discuss a strategic issue, share information on business development activities, brainstorm on how to seize an opportunity or address a challenge, or to discuss options and make a decision. Participants then know what to expect and how to prepare.

If the meeting has no objective – or the only objective is that the leader hasn’t seen his team in a while – cancel it. (There are better ways to reconnect with your team than to pull them all into a room for no clear reason!) If you constantly find yourself trying to think of an objective 10 minutes before the meeting, either hold the meeting less often, or sit down once a quarter and create a schedule in advance.

Mistake 2: No focused agenda. Even when the objective is clear, the convener may not issue an agenda – a clear schedule of how the meeting will proceed – or will use vague agenda items (eg, “Market research” followed by “general updates”). Some leaders cannot resist the temptation to clutter up the agenda with other small items –the “kitchen sink” approach.

Preparing for such a large meeting requires some forethought and serious planning. Based on the objective of the meeting, force yourself to limit the agenda to the items that are most crucial to you, your team and your business. To do this right, have some informal discussions beforehand with relevant colleagues to identify what is important to them. Then email the agenda — with a timeline that allocates a certain number of minutes to each item — to people well in advance, so that they come prepared. (If you really don’t have time to do this, consider having a deputy do it.) Once you’re in the meeting, stick to the agenda items and time schedule. This prevents participants from wandering off topic and helps the team to finish the meeting on time.

Mistake 3: Not hearing from everyone in the room. Leaders allow the usual suspects dominate the discussions, while others remain largely quiet. You can do three things to get more people engaged:

Get serious about participants who talk more than their fair share. You know who they are. Tell them you appreciate their input but that their vociferousness discourages other people from participating. Interrupt them (nicely) if necessary: “Excuse me George, I’m sorry to interrupt you, but I want to make sure we have time to hear from everyone.”

Give the podium to different participants. You can create air time for quiet team members by giving them a specific slot on the agenda.

Ask direct questions and get opinions from different participants as you go. Are we missing something? Have we thought this through from all possible angles? Cold call people who don’t speak up.

Mistake 4: Debates that don’t go anywhere. When leaders fail to guide discussants away from subjective perspectives, or participants haven’t come prepared, people end up leaving the meeting without a clear course of action. Encourage attendees to come prepared and present their arguments backed up by numbers and facts. For instance, you’ll get more and better ideas out of participants if you send around a memo ahead of time, and tell them they’re expected to read it, than if you make them sit through a PowerPoint and then tell them to brainstorm.

Mistake 5: Not reaching consensus on a course of action. After all that talking, it’s important that people know what to do next or they’ll feel like the meeting was a waste of time. Set aside time at the end of each meeting to agree on an action plan and decide who is accountable for what. Keep a record of the actions to be taken, who is responsible for them, and what the deadlines will be. If the meeting identified any new issues to be further explored, schedule follow-up discussions as needed.

Mistake 6: Missing the opportunity to remind people of the big picture. A staff meeting can be an opportunity to offer public praise, reiterate a corporate goal, inspire people, and remind them of your strategic vision. Once the agenda has been covered, or your prearranged time is up, and actions have been agreed, wrap up the meeting by recognizing participants’ hard work and reminding all attendees how their work (and the agreed-upon action items) contribute to each other’s success and how they link to the bigger picture.

Remember that staff meetings are extremely expensive when you account for everyone’s time. Treat them with the attention and care you would any major investment, and you’ll find that your team soon takes them more seriously.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers